Abstract

Background

OX40 has been widely studied as a target for immunotherapy with agonist antibodies taken forward into clinical trials for cancer where they are yet to show substantial efficacy. Here, we investigated potential mechanisms of action of anti-mouse (m) OX40 and anti-human (h) OX40 antibodies, including a clinically relevant monoclonal antibody (mAb) (GSK3174998) and evaluated how isotype can alter those mechanisms with the aim to develop improved antibodies for use in rational combination treatments for cancer.

Methods

Anti-mOX40 and anti-hOX40 mAbs were evaluated in a number of in vivo models, including an OT-I adoptive transfer immunization model in hOX40 knock-in (KI) mice and syngeneic tumor models. The impact of FcγR engagement was evaluated in hOX40 KI mice deficient for Fc gamma receptors (FcγR). Additionally, combination studies using anti-mouse programmed cell death protein-1 (mPD-1) were assessed. In vitro experiments using peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) examining possible anti-hOX40 mAb mechanisms of action were also performed.

Results

Isotype variants of the clinically relevant mAb GSK3174998 showed immunomodulatory effects that differed in mechanism; mIgG1 mediated direct T-cell agonism while mIgG2a acted indirectly, likely through depletion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) via activating FcγRs. In both the OT-I and EG.7-OVA models, hIgG1 was the most effective human isotype, capable of acting both directly and through Treg depletion. The anti-hOX40 hIgG1 synergized with anti-mPD-1 to improve therapeutic outcomes in the EG.7-OVA model. Finally, in vitro assays with human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (hPBMCs), anti-hOX40 hIgG1 also showed the potential for T-cell stimulation and Treg depletion.

Conclusions

These findings underline the importance of understanding the role of isotype in the mechanism of action of therapeutic mAbs. As an hIgG1, the anti-hOX40 mAb can elicit multiple mechanisms of action that could aid or hinder therapeutic outcomes, dependent on the microenvironment. This should be considered when designing potential combinatorial partners and their FcγR requirements to achieve maximal benefit and improvement of patient outcomes.

Keywords: Immune modulatory, Monoclonal antibody, co-stimulatory molecules

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of anti-OX40 monotherapy in murine preclinical models but while clinical trials have demonstrated good safety profiles, therapeutic effects have been disappointing.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

In this study, we have made use of human OX40 knock-in mice to dissect the impact isotype has on the mechanism of action of anti-human OX40 antibodies; specifically isotype variants of GSK3174998, an anti-human OX40 antibody that has been investigated clinically. We demonstrate that the hIgG1 isotype is the most effective human isotype in our models with the capacity to synergize with anti-mouse-programmed cell death protein-1 and that it can act via both Treg depleting and CD8 activating mechanisms depending on the microenvironment.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Our study emphasizes the importance of understanding the mechanisms of action of therapeutic antibodies and how that needs to be combined with an understanding of the environment they are acting in, in order to deliver their therapeutic potential. Thus for OX40 to become a viable monotherapy target it may need to be more selectively matched to appropriate tumors. Our study also has implications for how antibody combination therapies are evaluated clinically and the impact of the isotype of each antibody on the availability of Fc gamma receptors and hence the mechanisms of action of both antibodies.

Introduction

Antibody immunotherapy now benefits a proportion of patients with cancer, most notably after checkpoint blockade in melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer.1 2 However, with responses only seen in some patients and resistance occurring in others, alternative strategies are being explored.3–5 One option is immune stimulation through tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (TNFRSF) members such as OX40 (CD134).6–10 OX40 is important for T-cell proliferation, survival and effector function,11–14 with agonistic antibodies evoking antitumor activity in several preclinical models,8 15–19 leading to the development of a number of clinical candidates. However, monotherapy trials have been disappointing, with limited evidence for efficacy (reviewed in20) with checkpoint blockade combinations now being explored.21–26 The addition of anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) to anti-OX40 monotherapy is typically beneficial in preclinical models,21 22 25 although some studies show anti-PD-1 has a negative impact on anti-OX40 monotherapy,23 24 leading to considerations of the treatment sequence and the importance of the immune status in each model. One aspect that is underexplored is the impact that isotype can make on monoclonal antibody (mAb) immunotherapy and its mechanism of action, particularly in the context of combination therapy.

Anti-mOX40 mAb mechanisms of action are clearly influenced by isotype and interactions with Fc gamma receptors (FcγR), with mIgG1 engaging the inhibitory FcγRIIB to trigger OX40 signaling and T-cell activation, and mIgG2a depleting OX40+cells, particularly regulatory T cells (Tregs).16 27 28 Studies have also shown an impact of isotype on anti-PD-1.29–31 Therefore, as trials look to combine mAb targeting these molecules, an understanding of optimal FcγR interactions for clinically relevant anti-hOX40 mAb is required.

Previously, we reported an hOX40 knock-in (KI) mouse strain, whereby anti-hOX40 mAb with mouse Fc regions demonstrated both antigen-specific CD8+OT I T-cell expansion and antitumor responses.16 Here, we extend these studies to examine the humanized clinically relevant anti-hOX40 hIgG1 antibody GSK3174998, dissect the impact of FcγRs on its mechanisms of action and consider how these may influence potential combinations.

Results

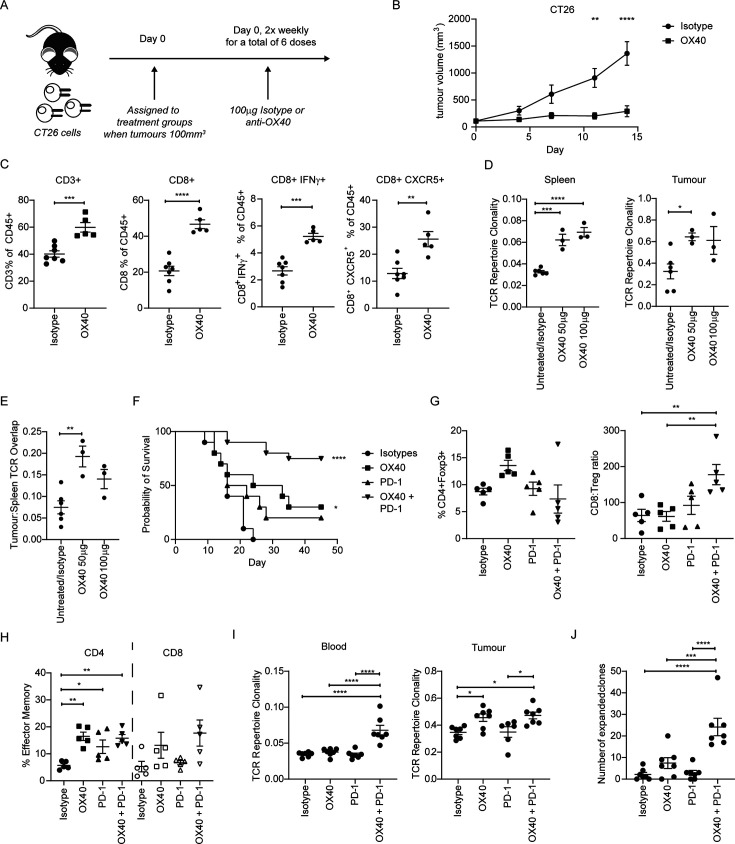

Anti-mOX40 increases effector CD8+ T cells in responsive models

First, using the anti-mOX40 agonist mAb, OX86,32 we showed that monotherapy treatment of different tumors delivered variable efficacy (figure 1A,B and online supplemental figure 1A-E). There was no impact on tumor growth in LLC and B16 tumors in response to anti-mOX40 treatment whereas EMT6, A20 and CT26 tumors were controlled to varying degrees. To investigate the potential mechanisms involved, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were analyzed from mice challenged with CT26 tumors. TILs harvested on day 10 after anti-mOX40 mAb treatment had more CD3+ and CD8+ cells compared with isotype control, alongside more CD8+IFN-γ+ and CD8+CXCR5+ cells (figure 1C), indicating that they had more effector CD8+cells.33 Similar results were obtained from A20 tumors; CD8+T cells isolated from tumors at various time points showed several immunomodulatory genes were altered by anti-mOX40 mAb treatment (online supplemental figure 2A). Furthermore, an increase in CD8+Ki67+ (35.3% vs 24.3%), CD8+PD-1+ (57.1% vs 46.8%) and CD8+GzmB+ (34.8% vs 20.47%) cells was observed (online supplemental figure 2B), supporting that OX40 treatment leads to an increase in proliferative CD8+T cells with effector function in the tumor. A significant increase in CD4+Ki67+ (27.7% vs 20%) and CD8+GzmB+ (6.2% vs 1.1%) cells was also seen in the blood on day 10 (online supplemental figure 2C). Furthermore, PD-1 was upregulated on both CD4 and CD8+T cells (8.2% vs 3.8% and 5.2% vs 3.3%, respectively) (online supplemental figure 2C) indicating anti-mOX40 mAb treatment increases activated CD4 and CD8 T cells with potential for increased functionality both within the tumor and systemically.

Figure 1.

anti-mOX40 rIgG1 mAb results in an activated immune response in CT26 syngeneic tumor models. (A) Schematic of mice challenged with 5×105 CT26 tumor cells and subsequent treatment with either isotype control or anti-mOX40 (OX86) mAb (100 µg) two times per week. (B) Growth curves of mice challenged with CT26 cells and treated as depicted in A; n=10 (similar trends observed in multiple studies). (C) Mice inoculated with 5×105 CT26 tumor cells were harvested 10 days post initial treatment with TILs assessed by flow cytometry for CD45+CD3+ (left panel), CD8+ (left middle panel), CD8+IFN-γ+ (right middle panel) and CD8+CXCR5+ (right panel). N=7 isotype control and n=5 for anti-mOX40, one experiment. (D) Mice inoculated with 5×105 CT26 tumor cells 7 days post treatment with indicated doses of anti-OX40. Spleens (left panel) and tumor (right panel) were harvested and assessed for TCR repertoire clonality; n=3 except the combined group of isotype and untreated where n=6, one experiment. (E) Analysis of the overlap of TCR CDR3 clones between spleen and tumor analyzed in D; n=3 except the combined group of isotype and untreated where n=6, one experiment. (F) Survival curves of mice challenged with 5×105 CT26 SC and treated with either anti-mOX40 (100 µg), anti PD-1 (200 µg) or combination of anti-mOX40 and anti-PD-1 dosed as outlined in A. n=10 for isotype, anti-mOX40 and anti-PD-1, n=20 for anti-mOX40+anti-PD-1. Similar trends were observed in multiple studies. (G–H) TILs harvested on day 10 and immunophenotyped for Treg (G—left panel), CD8:Treg ratio (G right panel) and effector memory cells (CD62L low CD44 high) (H). n=5, one experiment. (I) TCR repertoire clonality analysis for blood (left panel) and tumor (right panel) from CT26-bearing mice harvested on day 15; n=7, except for tumor sample treated with anti-PD-1 where n=6, one experiment. (J) Analysis of the overlap of TCR CDR3 clones between blood and tumor. N=7, one experiment ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001, **p<001, *p<0.05 mean±SEM B. Sidak’s multiple comparison one-way ANOVA, C and E—unpaired t-test, D–E—Dunnet’s multiple comparison one-way ANOVA, F—log-rank test, G–J—Tukey’s multiple comparison one-way ANOVA. ANOVA, analysis of variance; mAb, monoclonal antibody; PD-1, programmed cell death protein-1; TCR, T-cell receptor; TIL, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte; Treg, regulatory T cells.

jitc-2023-008677supp002.pdf (446.9KB, pdf)

To explore other aspects of the T-cell response, the T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire in CT26 tumor-bearing mice was examined after 50 or 100 µg anti-mOX40 mAb. Anti-mOX40 mAb-treated mice showed an increase in TCR clonality in the spleen compared with a pooled group of untreated and isotype controls (figure 1D left panel). Untreated and isotype control groups were not significantly different and so pooled to allow more robust statistical evaluation (online supplemental figure 2D). Likewise, an increase in TCR clonality was also seen in the tumor (figure 1D right panel). Furthermore, the overlap between clones identified in spleen and tumor was increased (figure 1E). These data indicate that anti-mOX40 mAb drives activation of T cells, promoting clonality and enhancing effector functionality.

While anti-mOX40 mAb monotherapy showed some therapeutic benefit in the models above, the effects were limited. Therefore, a combination with checkpoint blockade was investigated. Given the evidence for an upregulation of PD-1 on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells after anti-mOX40 mAb treatment (online supplemental figure 2C) and,34 we investigated a combination with anti-PD-1 mAb. Treatment of CT26 tumor-bearing mice with anti-mouse PD-1 (mPD-1) mAb monotherapy did not produce significant enhancement of survival (figure 1F). While anti-mOX40 mAb monotherapy again showed a modest but significant improvement in survival, the combination with anti-mPD-1 mAb resulted in far greater survival; ~75% of animals survived >50 days compared with~30% with anti-mOX40 mAb alone (figure 1F). The long-term survivors were fully protected from subsequent rechallenge with CT26 (online supplemental figure 3A), providing evidence of effective memory generation.

Given the potential impact of dosing schedules on combination therapy,23 24 we next investigated differences in administration schedules, comparing concurrent or sequential treatments. In the CT26 model, concurrent delivery of anti-mOX40 and anti-mPD-1 mAb resulted in greater efficacy than sequential delivery (online supplemental figure 3B) and so subsequent investigations continued with this regimen. To evaluate the impact of the combination on TILs, NanoString was performed. The anti-mOX40 and anti-mPD-1 combination increased T cell and immunomodulatory gene transcription in TILs, although the difference from anti-mOX40 monotherapy was subtle (online supplemental figure 3C). TIL immune phenotyping showed limited changes in the Tregs (figure 1G left panel) but significant increases in the CD8:Treg ratio in mice treated with the combination (figure 1G right panel). The CD4+effector memory (EM) population (CD62lowCD44high) was increased, with the CD8+EM population unchanged (figure 1H). Further investigation showed that the combination significantly increased the CD8+Ki67+ and CD4+Tbet+ T-cell populations in the blood over isotype or anti-PD-1 monotherapy, with a similar trend in the number of CD8+GzmB+ T cells (online supplemental figure 3D). However, in TILs the combination treatment resulted in a statistically significant increase in the CD8+GzmB+ population (online supplemental figure 3E) but not CD8+Ki67+ or CD4+Tbet+ T cells (online supplemental figure 3E), further illustrating the importance of understanding both tumor-localized and systemic responses. Serum levels of effector cytokines interferon (IFN)-γ (online supplemental figure 3F), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (online supplemental figure 3G), interleukin (IL)-6 (online supplemental figure 3H) and IL-2 (online supplemental figure 3I) were also significantly increased in the combination arm, to a greater extent than the single treatments. When TCR clonality was examined, only the combination showed an increase in the blood (figure 1I left panel) whereas in the tumor, both anti-mOX40 monotherapy and the combination resulted in a significant increase (figure 1I right panel). The combination did not increase TCR clonality in the tumor above that induced by the anti-mOX40 monotherapy, suggesting that OX40 modulation drives the increase in the tumor. However, the combination increased the number of overlapping expanded clones above that of either monotherapy, supporting the need for both treatment arms (figure 1J).

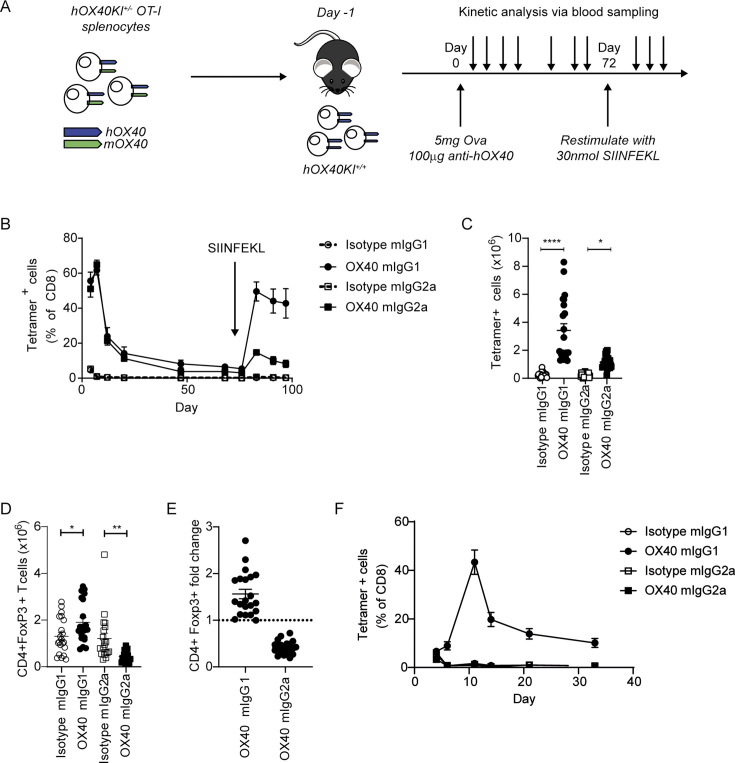

Anti-hOX40 mIgG1 can act directly on antigen-specific T cells

To help translate these findings, we made use of a clinically relevant humanized anti-hOX40 mAb (GSK3174998) and hOX40 KI mice.16 GSK3174998, was recently explored in a Phase 1/2a trial (ENGAGE-1 - NCT02528357).26 35 To explore its potential mechanisms of action in our murine preclinical models, it was isotype switched to mIgG1 and mIgG2a isotypes which exhibit differing FcγR binding profiles36 37 and effector functions for anti-TNFRSF mAbs.16 27 38–41 mIgG2a interacts strongly with activating FcγR and can elicit target cell deletion, whereas mIgG1 binds preferentially to the inhibitory FcγRII, evoking receptor crosslinking leading to agonism and target cell activation.

To explore the impact on antigen-specific CD8 T-cell expansion, hOX40KIhet OT-I Tghet cells were adoptively transferred into hOX40KIhom recipients before treatment with ovalbumin (OVA) alongside anti-hOX40 mIgG1 or mIgG2a and monitoring for CD8+OT-I+ T cells (figure 2A). Anti-hOX40 mIgG1 and mIgG2a expanded CD8+OT-I+ T cells in the blood equivalently during the primary response, although only the mIgG1 group mounted a robust secondary response when challenged with the SIINFEKL ovalbumin peptide (figure 2B). These observations, including the mIgG1-dependent memory response, mirror data generated with other antibodies targeting hOX40.16 Treatment with both isotypes also showed a significant expansion of CD8+OT-I+ T cells in the spleen, although to a greater extent with anti-hOX40 mIgG1 (figure 2C). CD4+Foxp3+ (Treg) cells expanded in mice treated with the anti-hOX40 mIgG1, but significantly decreased after mIgG2a treatment (figure 2D). This consistently resulted in a fold change of CD4+Foxp3+ T cells >1 with anti-hOX40 mIgG1 and <1 with anti-hOX40 mIgG2a (figure 2E).

Figure 2.

anti-hOX40 mIgG1 and mIgG2a mAb are costimulatory in the OT-I/hOX40KI model. (A) Schematic of the experimental model; hOX40het OT-I cells are transferred into hOX40KIhom mice, immunized with ovalbumin in the presence of anti-hOX40 mAb and various cells measured by flow cytometry before recall stimulation with SIINFEKL. (B) Expansion of tetramer-positive OT-I cells in hOX40KIhom recipients. Isotype mIgG1, anti-hOX40 mIgG1 and anti-hOX40 mIgG2a n=4, Isotype mIgG2a n=3, representative of two independent experiments. Numeration of OT-I (C) and Treg (D) cells in hOX40KIhom spleens harvested on day 4 pooled from six independent experiments. Isotype mIgG1 and anti-hOX40 mIgG1 n=21, isotype mIgG2a and anti-hOX40 mIgG2a n=20, two mice per group were excluded due to no OT-I response. (E) Treg fold induction pooled from six independent experiments anti-hOX40 mIgG1 n=21 and anti-hOX40 mIgG2a n=20. (F) As in A except hOX40het OT-I purified CD8+T cells transferred in wildtype C57BL/6 recipients, n=4, representative of two independent experiments. C–E analyzed as one-way analysis of variance, Sidak’s multiple comparison. ****p<0.0001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 mean±SEM. KI, knock-in; mAb, monoclonal antibody; Treg, regulatory T cells.

To explore whether GSK3174998 was acting via different mechanisms dependent on isotype, purified hOX40KIhet OT-I Tghet CD8+T cells were adoptively transferred into wildtype (WT) C57BL/6 recipient mice, where the anti-hOX40 antibody can act only on the adoptively transferred cells, and the experiment was repeated. The anti-hOX40 mIgG1 again expanded the CD8+OT-I+ T cells (figure 2F), supporting a mechanism of direct activation on the CD8+T cells. In contrast, the mIgG2a variant had no effect, indicating it causes CD8+OT-I+ T-cell expansion indirectly, most likely through Treg depletion.

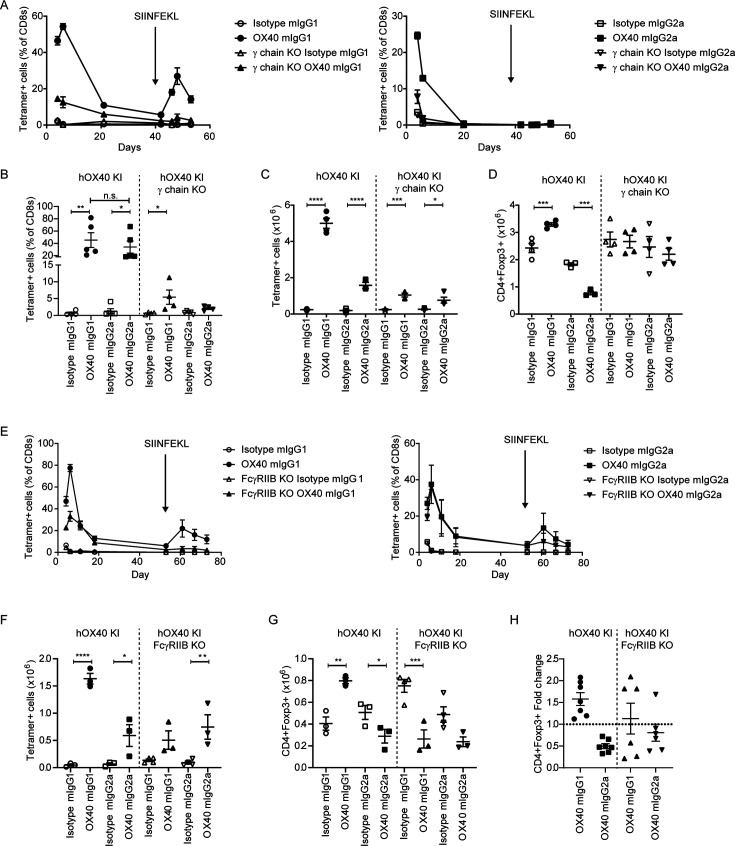

Anti-hOX40mIgG1 requires both activating and inhibitory FcγR for optimal activity

Given this clear isotype-dependent effect, we investigated the role of different FcγR in the CD8+OT-I+ T-cell expansion. Accordingly, hOX40KI mice were crossed with either Fcγ chain knock-out (KO) or FcγRIIB KO mice. Fcγ chain KO mice lack expression of all activating FcγR, preventing antibody-mediated target cell deletion.42 43 In contrast, FcγRIIB loss prevents the receptor crosslinking required for the agonistic activity of anti-TNFRSF antibodies.39–41 On adoptive transfer of hOX40KIhet OT-I Tghet splenocytes into hOX40KIhom Fcγ chain KO mice, responses to both anti-hOX40 mIgG1 and mIgG2a were reduced (figure 3A). The response to anti-hOX40 mIgG2a was almost completely lost as expected if depletion is a key component of this mechanism of action (figure 3A right panel). More surprizing was the significant reduction in response to anti-hOX40 mIgG1 mAb, presuming receptor crosslinking is important for the activity of this isotype, given FcγRIIB expression is retained and competition from activating FcγR reduced (figure 3A left panel). Comparison of the peak responses across multiple experiments confirmed this loss of response with both isotypes of anti-hOX40 mAb, although the anti-hOX40 mIgG1 retained activity significantly above that of the isotype control, unlike the anti-hOX40 mIgG2a, suggestive that the mIgG2a response was disrupted to a greater extent (figure 3B). To address whether this was restricted to the blood, spleens were harvested on day 4 and T-cell populations enumerated. Both anti-hOX40 isotypes, in both strains, showed a significant increase in CD8+OT-I+ T cells (figure 3C) although the absolute numbers were lower in the Fcγ chain KO strain. As previously shown, the anti-hOX40 mIgG2a mAb decreased the number of Treg in the hOX40KI strain but this reduction was lost in the hOX40KIhom Fcγ chain KO mice (figure 3D). These data indicate that the mIgG2a-mediated loss of Tregs in hOX40KIhom mice occurs through depletion mediated via activating FcγR. More surprisingly, the increase in Treg after anti-hOX40 mIgG1 hOX40KIhom was also lost in hOX40KIhom Fcγ chain KO mice (figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Anti-hOX40 mIgG1 mAb requires both activating and inhibitory FcγR for activity. hOX40het OT-I cells were transferred into transferred into hOX40KIhom, hOX40KIhomγ chain KO or hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO mice and then immunized as in figure 2A. (A) Response to anti-hOX40 mIgG1 (left panel) or anti-hOX40 mIgG2a (right panel) n=4 except isotype mIgG2a in hOX40KIhom where n=5. One mouse was excluded from anti-hOX40 mIgG1 in hOX40KIhom recipients due to a lack of OT-I response hence n=4. Representative of two independent experiments. (B) Peak OT-I responses in blood from hOX40KIhom and hOX40KIhomγ chain KO recipients n=5 except Isotype mIgG1 in both hOX40KIhom and hOX40KIhomγ chain KO where n=4. One of two independent experiments. Splenic analysis of OT-I (C) and CD4+Foxp3+ (D) T cells on day 4 post OVA (5 mg) and antibody (100 µg) challenge. N=4 except for anti-hOX40 mIgG2a in hOX40KI where n=3. One mouse excluded in isotype mIgG2a group in hOX40KIhom due to lack of staining hence n=3. Representative of two independent experiments. (E) OT-I kinetic responses in hOX40KIhom and hOX40KIhom FcγRIIBKO mice in response to anti-hOX40 mIgG1 (left panel) or anti-hOX40 mIgG2a (right panel) n=4 except Isotype mIgG1 in hOX40KIhom and Isotype mIgG2a in hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO mice where n=3. Representative of two independent experiments. (F–H) Splenic analysis of OT-I (F) and CD4+Foxp3+ (G) T cells on day 4 post ovalbumin (5 mg) and antibody (100 µg) challenge. N=3 for all hOX40KI recipient groups, n=4 for all hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO except for anti-hOX40 mIgG1 and anti-hOX40 mIgG2a treated groups where one mouse was excluded as due to lack of OT-I response hence n=3. One of two independent experiments. (H) Treg fold induction pooled from two independent experiments, n=7 for hOX40KIhom anti-hOX40 mIgG1 and mIgG2a, n=6 for hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO anti-hOX40 mIgG1 and mIgG2a. ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 mean±SEM B–D, and F and G—one-way analysis of variance with Sidak’s multiple comparison. mAb, monoclonal antibody; FcγR, Fc gamma receptors; KI, knock-in; KO, knock-out; Treg, regulatory T cells.

To investigate the role of FcγRIIB, the experiments were repeated in hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO mice. As might be anticipated if FcγRIIB was providing crosslinking for the anti-hOX40mIgG1 mAb, the magnitude of the CD8+OT-I+ T-cell response was reduced in the hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO recipients (figure 3E left panel). In contrast, the response to the anti-hOX40 mIgG2a was unaffected by the loss of the inhibitory receptor (figure 3E right panel). Analysis of splenocytes on day 4 also showed less expansion of CD8+OT-I+ cells in the hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO recipients treated with anti-hOX40 mIgG1 compared with WT hOX40KIhom recipients while the response to anti-hOX40 mIgG2a mAb was significantly above isotype in both strains (figure 3F). Analysis of splenic Tregs showed the reduction in numbers mediated via anti-hOX40 mIgG2a mAb was maintained in both WT hOX40KIhom and hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO strains (figure 3G and H), although to a lesser extent in the hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO strain. The increased number of Tregs and positive fold change seen in response to anti-hOX40 mIgG1, however, was not consistently maintained in hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO mice (figure 3G and H). The loss of either activating or inhibitory FcγR had a significant impact on the ability of the anti-hOX40 mIgG1 isotype to elicit CD8+OT-I+ T-cell expansion, possibly indicating that both are mediating antibody crosslinking.

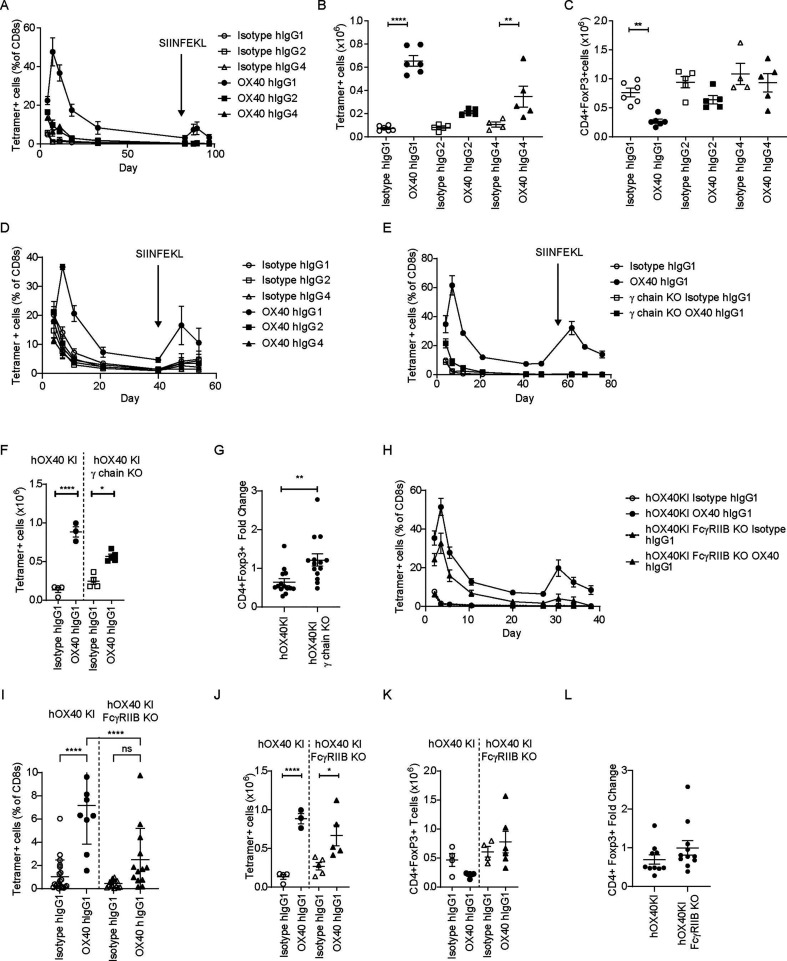

Anti-hOX40 hIgG1 engages with both activating and inhibitory FcγR to mediate antigen-specific T-cell expansion

We next examined the effect of human isotypes, including the hIgG1 isotype previously used in the clinic. Although this experimental set-up involves interactions between human antibodies and mouse FcγR, the interspecies similarities and differences are known16 37 making it possible to interpret the findings and infer likely mechanisms of action for exploitation in patients. Evaluating hIgG1, hIgG2 and hIgG4 variants of the anti-hOX40 mAb, only the hIgG1 was able to robustly expand CD8+OT-I+ T cells in the blood, although the secondary response to SIINFEKL was lower than might be expected (figure 4A). Splenic CD8+OT-I+ T cells also showed the greatest expansion in response to anti-hOX40 hIgG1 (figure 4B). Only the hIgG1 anti-hOX40 mAb resulted in a statistically significant reduction in the numbers of splenic Tregs (figure 4C). To understand whether anti-hOX40 hIgG1 was capable of acting directly on the transferred cells, hOX40KIhet OT-I Tghet splenocytes were transferred into WT C57BL/6 recipient mice. As before, only the hIgG1 anti-hOX40 mAb expanded the transferred cells (online supplemental figure 4A). To further confirm the direct effect of hIgG1 anti-hOX40 mAb on the antigen-specific CD8+T cells, purified hOX40KIhet CD8+OT I Tghet cells were transferred into WT recipients and stimulated with OVA and anti-hOX40 mAb. Again, only anti-hOX40 hIgG1 expanded the CD8+OT-I+ cells (figure 4D).

Figure 4.

anti-hOX40 hIgG1 monoclonal antibody activity requires both activating and inhibitory FcγR. hOX40het OT-I cells were transferred into hOX40KIhom, hOX40KIhomγ chain KO or hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO mice and then immunized as in figure 2A. (A) OT-I kinetic responses in hOX40KIhom recipients in response to challenge with anti-hOX40 hIgG1, hIgG2 and hIgG4 (solid lines) or isotype controls (dashed lines) n=3 except for Isotype hIgG4 where n=2 due to sick mouse being culled at start of experiment. Representative of two independent experiments. Splenic analysis of OT-I (B) and CD4+Foxp3+ (C) T cells on day 4 post OVA (5 mg) and antibody (100 µg) challenge. Isotype and anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=6, isotype hIgG2, anti-hOX40 hIgG2 and anti-hOX40 hIgG4 n=5 and Isotype hIgG4 n=4. Representative of two (B) and three (C) independent experiments. (D) As in A except hOX40het OT-I purified CD8+T cells transferred in WT C57BL/6 recipients. OT-I kinetic responses in WT recipients in response to challenge with anti-hOX40 hIgG1, hIgG2 and hIgG4 (solid lines) or isotype controls (dashed lines) Isotype and anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=5, isotype and anti-hOX40 hIgG2 n=4, isotype and anti-hOX40 hIgG4 n=3. Representative of two independent experiments. (E) OT-I kinetic responses in hOX40KIhom and hOX40KIhomγ chain KO mice in response to anti-hOX40 hIgG1, isotype hIgG1 n=4, anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=3 due to one mouse excluded based on lack of OT-I response, hOX40KIhomγ chain KO Isotype hIgG1 n=5, hOX40KIhomγ chain KO anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=4. Representative of two independent experiments. (F) Splenic analysis of OT-I T cells on day 4 post OVA (5 mg) and antibody (100 µg) challenge. hOX40KIhom Isotype hIgG1, anti-hOX40 hIgG1 and hOX40KIhomγ chain KO isotype hIgG1 n=4, hOX40KIhomγ chain KO anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=5. (G) Splenic analysis of CD4+Foxp3+ T-cell fold change relative to Isotype control on day 4 post OVA (5 mg) and antibody (100 µg) challenge. hOX40KIhom anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=14, hOX40KIhomγ chain KO anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=14. (H) OT-I kinetic responses in hOX40KIhom and hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO mice in response to OVA and anti-OX40 hIgG1. hOX40KIhom—isotype hIgG1 n=16, OX40 hIgG1 n=12 due to four mice being excluded based on lack of response. hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO—isotype hIgG1 n=19, hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=15 due to four mice being excluded based on lack of response. Pooled from four independent experiments. (I) Blood analysis of OT-I T cells on day 40 post OVA (5 mg) and antibody (100 µg) challenge. hOX40KIhom isotype hIgG1 n=12, hOX40KIhom anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=10 due to two mice being excluded due to lack of response, hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO isotype hIgG1 n=15 and hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=13 due to two mice being excluded due to a lack of response, data pooled from three independent experiments. (J) Splenic analysis of OT-I T cells on day 4 post OVA (5 mg) and antibody (100 µg) challenge. hOX40KIhom Isotype hIgG1 and anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=4, hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO isotype hIgG1 and FcγRIIB KO anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=5. (K) Splenic analysis of CD4+Foxp3+ T-cell numbers on day 4 post OVA (5 mg) and antibody (100 µg) challenge. hOX40KIhom Isotype hIgG1 n=4, anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=6, hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO isotype hIgG1 n=4 and hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=6. (L) Splenic analysis of CD4+Foxp3+ T-cell fold change relative to isotype control on day 4 post OVA (5 mg) and antibody (100 µg) challenge. hOX40KIhom n=10, hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO n=11 data pooled from two independent experiments. ****p<0.0001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 mean±SEM B–C, F and J—Sidak’s multiple comparison one-way ANOVA, G—unpaired t-test, I—Tukey’s multiple comparison one-way ANOVA. ANOVA, analysis of variance; FcγR, Fc gamma receptors; KI, knock-in; KO, knock-out; OVA, ovalbumin; WT, wildtype.

Given these observations, we focused on the importance of the different FcγR. hIgG1 interacts with multiple activating mouse and human FcγR and so we hypothesized that these interactions were responsible for the observed reduction in splenic Tregs. To test this, hOX40KIhet OT-I Tghet cells were transferred into hOX40KIhom or hOX40KIhom Fcγ chain KO mice prior to OVA and anti-hOX40 mAb stimulation. In the hOX40KIhom Fcγ chain KO strain the expansion of CD8+OT-I+ T cells was significantly lower than in the hOX40KIhom strain and insufficient to elicit a secondary response to SIINFEKL peptide (figure 4E). Analysis of splenocytes on day 4 showed reduced expansion of CD8+OT-I+ T cells in the hOX40KIhom Fcγ chain KO strain (figure 4F). No consistent Treg depletion was observed in the hOX40KIhom Fcγ chain KO mice (figure 4G; online supplemental figure 4B), resulting in a significant difference between the Treg fold change induced by anti-hOX40 hIgG1 in hOX40KIhom versus hOX40KIhom Fcγ chain KO recipients. As there was still some expansion of CD8+OT-I+ T cells in the hOX40KIhom Fcγ chain KO mice above the isotype control, the role of FcγRIIB was explored in hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO mice. Despite variation between experiments, pooled data showed a slight reduction in expansion of CD8+OT-I+ cells in hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO compared WT hOX40KIhom mice (figure 4H and online supplemental figure 4C). Likewise, as the response contracted into memory phase (day 40), significantly greater percentages of CD8+OT-I+ T cells were observed in the hOX40KIhom strain than the hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO mice (figure 4I) suggesting that FcγRIIB has a role in the generation or persistence of memory. This translated into a greater secondary response in hOX40KIhom versus hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO mice (online supplemental figure 4D). Similarly, in the spleen at day 4, CD8+OT-I+ T cells significantly increased in both strains (figure 4J). These data indicate that there is an initial expansion of CD8+OT-I+ T cells in the hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO mice but that the response is not maintained, which leads to a lower overall recall response. Analysis of splenic Tregs in the hOX40KIhom FcγRIIB KO strain was inconclusive when analyzed as individual experiments (figure 4K); however, when analyzed across multiple experiments, a fold change <1 (figure 4L) was seen, suggesting FcγRIIB is not important for Treg depletion. Thus, these data suggest that anti-hOX40 hIgG1 mAb mediates its effects through the depletion of Tregs via the activating FcγR as well as by acting directly on the CD8+T cells with cross-linking provided by FcγRIIB.

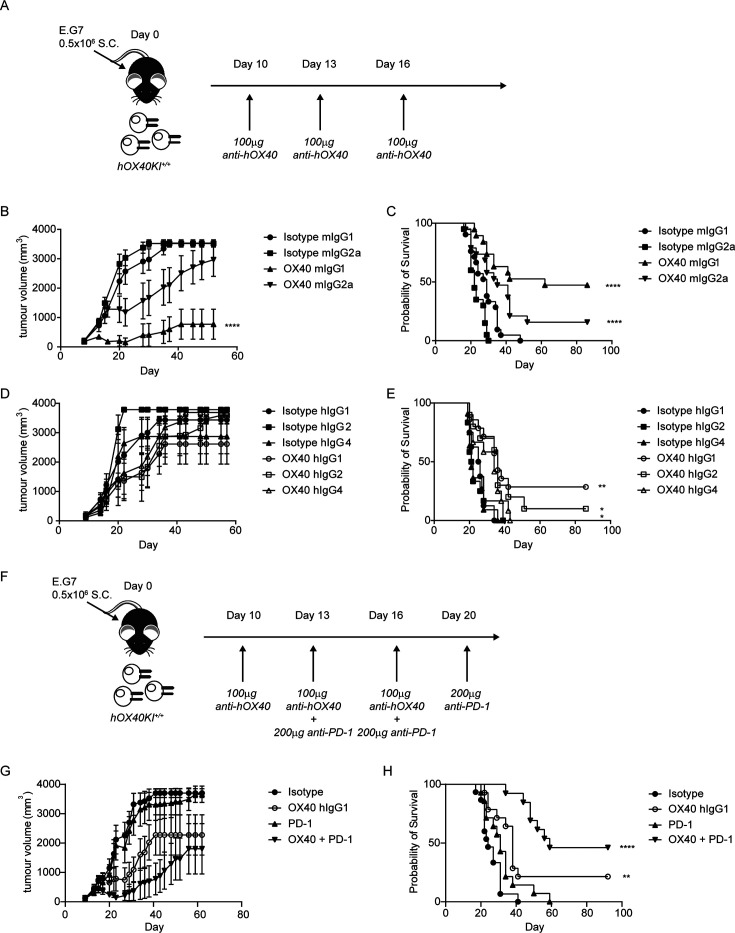

Anti-hOX40 hIgG1 combination with anti-mPD-1 improves efficacy in EG7-OVA model

Next, we explored the therapeutic efficacy of the various anti-hOX40 mAb in a murine tumor model. Mice were challenged with E.G7-OVA thymoma cells and then treated once tumors had developed as outlined in figure 5A. Anti-hOX40 mIgG2a caused a slight delay in tumor growth (figure 5B) which resulted in 15% long-term survivors (>50 days) across three independent experiments (figure 5C). The anti-hOX40 mIgG1 resulted in a significant reduction in tumor growth (figure 5B) with 47% long-term survivors (figure 5C). For both isotypes, long-term survivors were protected from rechallenge with E.G7-OVA (online supplemental figure 5A,B). These data show that for this particular antibody, mIgG1 provides greater efficacy than mIgG2a and infer that depletion of Tregs may be less beneficial than direct CD8 activation. Given that anti-hOX40 hIgG1 had shown potential to mediate both depletion and direct activation we investigated its efficacy in the E.G7-OVA model versus hIgG2 and hIgG4. Although mean changes in tumor growth were not significantly different (figure 5D), anti-hOX40 hIgG1 gave more long-term survivors (28%) compared with hIgG2 (10%) or hIgG4 (0%) (figure 5E), with long-term survivors showing resistance to rechallenge with E.G7-OVA (online supplemental figure 5C). As the efficacy of the anti-hOX40 hIgG1 mAb in this model was relatively limited, and following our earlier results with anti-mOX40 mAb, combination with anti-mPD-1 mAb was assessed. As anti-mPD-1 efficacy is reduced when there is insufficient priming of CD8 T cells,44 a staggered dosing schedule, employing anti-hOX40 hIgG1 mAb first, as outlined in figure 5F, was used. Mice treated with anti-mPD-1 monotherapy showed no reduction in tumor growth, while those treated with anti-OX40 hIgG1 and the combination showed tumor control (figure 5G). Anti-mPD-1 monotherapy showed a marginal improvement in survival but with no long-term survivors whereas anti-hOX40 hIgG1 resulted in a significant improvement in survival with 21% long-term survivors (figure 5H), which was enhanced in the combination; 46% of mice surviving >90 days (figure 5H). In a following experiment where a staggered and concurrent dosing strategy were compared, we did not observe a significant difference in the strategies, suggesting that concurrent dosing is also effective in this model (online supplemental figure 5D-F). These data support combining anti-hOX40 and anti-mPD-1 mAb in the clinic to achieve improved tumor control compared with monotherapy.

Figure 5.

Combination of anti-hOX40 and anti-PD-1 is more efficacious than monotherapy. (A) Schematic of treatment regime used in B–D. (B) Growth curves of hOX40KIhom mice inoculated with 0.5×106 E.G7-OVA S.C. and then treated with 100 µg anti-hOX40 mIgG1 or mIgG2a or respective isotype controls on day 10, 13, 16. N=9 representative of three independent experiments. (C) Survival graph of hOX40KIhom mice challenged as in B. Isotype mIgG1 n=21, isotype mIgG2a n=20, anti-hOX40 mIgG1 n=19 and anti-hOX40 mIgG2a n=19 pooled from three independent experiments. (D) Growth curves of hOX40KIhom mice inoculated with 0.5×106 E.G7-OVA S.C. and then treated with 100 µg anti-hOX40 hIgG1, hIgG2 or hIgG4 or respective isotype controls on day 10, 13, 16. Isotype hIgG1 n=4, isotype hIgG2 n=7, isotype hIgG4 n=6, anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=7, anti-hOX40 hIgG2 n=5 and anti-hOX40 hIgG4 n=6, representative of two independent experiments. (E) Survival graph of hOX40KIhom mice challenged as in D. Isotype hIgG1 n=8, isotype hIgG2 n=12, isotype hIgG4 n=11, anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=14, anti-hOX40 hIgG2 n=10 and anti-hOX40 hIgG4 n=12 pooled from two independent experiments. (F) Schematic of E.G7-OVA tumors treated with anti-OX40 and anti-PD-1. (G) Growth curves of hOX40KIhom mice inoculated with 0.5×106 E.G7-OVA S.C. and then treated as detailed in F. Isotype combination n=8, anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=8, anti-PD-1 rIgG2a n=8 and anti-hOX40 hIgG1+anti-PD-1 rIgG2a n=7, representative of two independent experiments. (H) Survival plots of hOX40KI mice challenged as in F. Isotype combination n=15, anti-hOX40 hIgG1 n=14, anti-PD-1 rIgG2a n=14 and OX40 hIgG1+anti-PD-1 rIgG2a n=13. ****p<0.0001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 mean±SEM B—Sidak’s multiple comparison one-way analysis of variance on day 52 related to isotype control, C, E and H—log-rank test. KI, knock-in; OVA, ovalbumin; PD-1, programmed cell death protein-1.

Anti-hOX40hIgG1 can elicit cytokine secretion from hPBMCs and preferentially targets hTregs in antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity reporter assays

To see if the combination of anti-hOX40 hIgG1 and anti-PD-1 could trigger higher T-cell activity in humans, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors were activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 in the presence of anti-hOX40 hIgG1 and pembrolizumab and then analyzed for IFN-γ (online supplemental figure 6A) and TNF-α (online supplemental figure 6B) secretion. For both cytokines, the combination resulted in the highest secretion, suggesting that in patients, this combination may also result in a greater immune response.

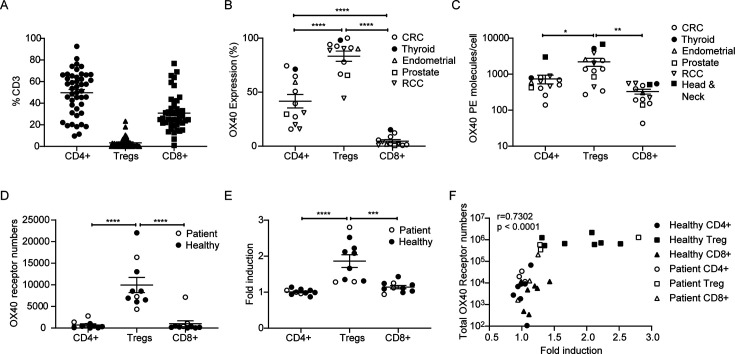

To consider which patient groups might benefit most from treatment with anti-hOX40 mAb, we analyzed the The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database for expression of OX40, OX40L and PD-L1. The expression of all three markers varied widely across tumor types (online supplemental figure 6C) however renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and sarcoma samples showed high levels, particularly of OX40 and so may be good options for combination therapy. To explore this further, we performed a flow cytometric analysis of patient tumor samples. The majority of CD3+TILS within resected tumor samples (Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Colorectal cancer (CRC), bladder, head and neck, thyroid, prostate, cervical, endometrial, gastric and RCC) were CD4+, with lower numbers of CD8+T cells and a minority of Treg (figure 6A). However, OX40 on these T-cell subsets was inversely correlated with their cellular frequency, with both percent OX40 positivity and number of molecules/cells being highest on Treg>CD4+>CD8+ T cells, as indicated previously45–47 (figure 6B and C). These data suggest that anti-hOX40 mAb might preferentially target Tregs and CD4+effectors over CD8+T cells. This hierarchy was also observed when PBMCs, isolated from healthy donors or patients with cancer, were activated for 2 days, with Tregs showing the greatest number of OX40 receptors/cell, followed by CD4+effectors and CD8+T cells (figure 6D). Given that in the hOX40KI mouse model, the anti-hOX40 hIgG1 mAb depleted Tregs in the presence of activating FcγR, an in vitro antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) reporter assay was performed to evaluate the ability of different T-cell subsets to engage hFcγRIIIA (as a readout for depleting potential) once opsonised with mAb. To better mimic ongoing immune response in the tumor, healthy donor or patient PBMCs were activated in vitro with anti-CD3/anti-CD28, sorted into the respective cell populations, and then incubated with anti-hOX40 hIgG1 mAb and hFcγRIIIA-expressing reporter cells. Treg showed the greatest ability to engage hFcγRIIIA and induce luciferase expression (figure 6E), with the number of OX40 receptors strongly correlated with luciferase induction across all cell types (figure 6F). This relationship between the number of OX40 receptors and the ability to engage hFcγRIIIA, suggests a potential mechanism of action in patients with Tregs the primary target for depletion.

Figure 6.

anti-hOX40 and anti-PD-1 combination increases cytokine production from hPBMC cultures. (A) Resected tumor samples were analyzed for CD4, CD8 and Treg populations n=45 for CD4 and CD8 and n=39 for Treg. (B) hOX40 expression on resected tumor samples on CD4+effectors, Tregs and CD8+T cells, n=12. (C) hOX40 receptor density on resected tumor samples was determined using BD Bioscience Quantibrite beads n=13. (D) Analysis of total OX40 receptor numbers/cell in healthy donor (filled circles) and patient (open circles) PBMCs activated for 2 days with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads n=10. (E) Fold induction of FcγRIII ADCC following healthy (filled circles) and patient (open circles) PBMCs activation for 2 days with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 beads, separation into cell type and then incubated with 10 µg/mL anti-OX40 (GSK3174998), n=10. (F) Correlation of total hOX40 receptor numbers (as determined by numbers of hOX40 receptors per cell × % hOX40+cells) with ADCC fold induction in response to anti-hOX40 treatment of cells isolated from healthy and patient donors activated as in D and E. n=10. ****p<0.0001, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05 mean±SEM B–E–Tukey’s multiple comparison one-way analysis of variance F–Pearson correlation. ADCC, antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity; FcγR, Fc gamma receptors; PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PD-1, programmed cell death protein-1; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; Treg, regulatory T cells.

Discussion

In agreement with previous reports, we showed that anti-mOX40 monotherapy could be efficacious in several mouse tumor models. When mouse IgG isotypes were examined, our results were consistent with those targeting other TNFRSF members,16 39 48 namely that mIgG1 was agonistic, acting directly on CD8+OT-I+ T cells while mIgG2a acted indirectly, most likely through depletion of Tregs. FcγR KO mice studies supported this hypothesis, with anti-OX40 mIgG2a activity and Treg depletion requiring the presence of the γ chain (activating FcγR), while loss of the FcγRIIB had no impact. In contrast, for anti-OX40 mIgG1 loss of both inhibitory and activating FcγR had an impact. The loss of the crosslinking activity of the FcγRIIB was predicted to impact the CD8+OT-I+ T-cell expansion,39–41 however, the reduction in the expansion in the γ chain KO strain was unexpected. While activating FcγR are typically considered to recruit effector immune cells with a depleting capacity, it is possible they could also provide crosslinking. The principal ability of all FcγR to evoke mAb:receptor cross-linking has been shown previously, with the reliance on FcγRIIB thought to reflect amenable expression patterns and location.49 50 The mIgG1 primarily interacts with mFcγRIIB and mFcγRIII, both of which are low-affinity receptors51 52 and so it is possible that on cells that lack the high-affinity FcγRI, such as natural killer cells and neutrophils, these low-affinity receptors combine to provide crosslinking. In the γ chain KO mice the mFcγRIII component is lost, resulting in crosslinking from only FcγRIIB and hence a potential reduction in expansion. These data are surprizing given that the same observation was not made for CD4041 or 4-1BB in tumor models39 but this may be reflective of OX40’s requirement for higher order oligomerization for signaling while CD40, at least, has been suggested to pre-exist in low order oligomerization28 53 and so may require lower levels of crosslinking. Alternatively, it may reflect that activating FcγR deliver additional signals into important immune cells (such as dendritic cells (DCs), serving to boost immune responses, as proposed previously.54 55

Expanding this analysis into the E.G7-OVA tumor model, we showed that for GSK3174998 antibodies, an mIgG1 isotype provides greater efficacy than mIgG2a. While this may suggest that direct CD8 activation would be the more effective mechanism in this model, previous studies with a panel of antibodies against hOX40 had not shown this isotype preference,16 indicating a potential epitope dependence.

To explore more clinically relevant settings, hIgG isotypes of GSK3174998 and their potential mechanisms of action were also explored. The hIgG1 variant resulted in the greatest expansion of CD8+OT-I+ T cells >hIgG2 and hIgG4, while also causing Treg loss. Further studies showed that as with the mIgG1, the hIgG1 variant was capable of acting directly on CD8+OT-I+ T cells, although more modestly than the mIgG1, suggesting that hIgG1 can act via both direct agonism and depletion of Tregs. Experiments in the FcγR KO mice supported this hypothesis as both the loss of the activating FcγR (γ chain KO) and FcγRIIB impacted the ability of the hIgG1 to expand CD8+OT-I+ T cells. Extending this analysis to the E.G7 tumor model, the hIgG1 isotype (GSK3174998) was again more effective than hIgG2 and hIgG4. While the hIgG1 showed similar attributes to both the mIgG1 (in terms of efficacy and mechanism) and mIgG2a (Treg depletion) it is important to note that in terms of FcγR engagement, structure and FcγR independent functions there are no direct homologues between mouse and human IgG51 and hence it can deliver both deletion an agonism unlike the mouse isotypes. Perhaps slightly more surprizing is the lack of efficacy with the hIgG2. hIgG2 antibodies have been shown capable of evoking powerful target receptor agonism in an FcγR independent manner (reviewed in56) when targeting various TNFR, due to the unique hinge of hIgG2.57 However, this effect is not seen in all antibodies; for example, the anti-4-1BB mAb urelumab but not utomilumab is rendered more agonistic as an hIgG2 than an hIgG1.58 Thus, it suggests that GSK3174998 may be more in line with utomilumab in that isotype switching to hIgG2 does not render it more agonistic and hence delivers a less impressive impact both in OT-I expansion and efficacy in the E.G7 tumor model than anticipated. Another interesting point is that despite showing properties similar to the mIgG1, the hIgG1 never performed as well as the mIgG1 in the E.G7 model (28% vs 47% long-term survivors, respectively). One possible explanation is the use of a human isotype engaging mouse FcγR; however, human isotypes, including hIgG1, have been shown to interact with mouse FcγR effectively to elicit cell depletion.52 Another possibility is that the capacity for engaging both activating and inhibitory FcγR results in competition for effector mechanisms which is detrimental to overall efficacy. As our knowledge of the interaction between hIgG and FcγR continues to increase, new mutations are being introduced into hIgG with the aim of increasing or decreasing affinity for different FcγR. Campos Carrascosa et al recently showed that an engineered anti-OX40 hIgG1-V12 mAb with increased binding to hFcγRIIB resulted in increased TIL proliferation compared with the WT hIgG1 antibody.28 While this approach looks promising, the availability of FcγR in the tumor microenvironment in different cancers will presumably prove crucial in determining whether increasing affinity for the inhibitory receptor is a fruitful line of development. Indeed, while our data suggests that the hIgG1 isotype should be the preferred isotype to take to the clinic, anti-OX40 hIgG1 mAb have shown limited efficacy in the clinic to date.26 59–61 There are several potential explanations for this lack of translation from preclinical models including (1) the relatively lower cytotoxicity potential of hIgG1 versus mIgG2a; (2) the higher affinity of hIgG1 for the human inhibitory receptor; (3) the upregulation of FcγRIIB in human tumors62 and (4) the relative paucity of Treg in human cancers versus murine models. Therefore, it maybe that OX40 hIgG1 would only be capable of having a clinical impact in tumors where Treg were (1) prevalent, (2) the main mechanism limiting immune response and (3) capable of deletion due to a permissive FcγR expression pattern. It has already been questioned whether Treg prevalence in many human tumors is sufficient to act as an effective immunomodulatory target63 and whether anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) mAb operate through Treg deletion in humans64 despite abundant and clear evidence in mouse models (including with human FcγR expressing mice).45 65 To evaluate this and deliver clinical benefit, it may be necessary to biopsy for sufficient Treg presence and amenable FcγR expression patterns in patients and optimize the OX40 mAb Fc for higher A:I ratio, through targeted mutations and/or glycoengineering.66

In considering these aspects, a limitation of our study is that the preclinical mouse models do not fully recapitulate the human FcγR expression profile seen in human tumors. A further limitation of our study is that it uses a chimeric human:mouse OX40 model. While we have previously shown that the hOX40KI model does broadly mimic expression patterns of human OX40,16 it more closely reflects the expression pattern of mouse OX40 and moreover, does not contain the human signaling domain and machinery, leading to potential differences to those observed in the clinic.

As introduced above, one of the strategies being explored in the clinic is the combination of anti-OX40 with anti-PD-1. In line with other preclinical studies combining PD-1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) axis blockade with anti-OX40 mAb,22 34 we were able to show improved therapy in both the CT26 and E.G7-OVA models (figures 2F,G and H). Furthermore, this combination increased IFN-γ and TNF-α production from healthy human donor cells (online supplemental figure 6A,B). Despite this, and a body of supportive preclinical data, results from clinical trials indicate this combination will not be transformative in patients.21 26 One possibility is that further understanding of dosage/scheduling is needed for the preclinical efficacy to be translated into the clinic. Different preclinical models have shown conflicting data as to whether concurrent treatment with anti-PD-1 and anti-OX40 is beneficial or detrimental.22–24 34 Wang et al investigated this based on responses to BMS-986178 in patients and comparison with their surrogate antibody OX40.23 in the CT26 model and showed that OX40 expression was lost following high receptor occupancy.25 Through modeling, they suggested that there may be a need for adjusting dosing and scheduling to achieve lower occupancy than is desired traditionally when using receptor-blocking entities such as checkpoint inhibitors.

Another consideration, especially when developing combinations of antibodies is the competition for FcγR. Here, we showed that anti-OX40 requires multiple FcγR for its maximal immune-stimulating properties (both in vivo and in vitro using hPBMCs), and while we did not directly investigate the FcγR requirement for the anti-PD-1, others have previously shown that FcγR engagement impacts the efficacy of anti-PD-1 mAb.29–31 Therefore, there is a possibility that competition for FcγR between the two mAbs could limit the combinatorial impact. Anti-PD-1 mAbs in the clinic are mostly hIgG4, selected for reduced capacity for FcγR engagement, however, they retain appreciable affinity for FcγRI,51 52 which likely limits their efficacy. Indeed Moreno-Vicente et al recently compared anti-PD-1 hIgG4 and anti-PD-1 hIgG4 FALA (Fc null) mAbs in mice expressing hFcγR, showing the Fc null variant gave enhanced effects.30 Although the immune context during immunization clearly differs from that in a tumor model, or patient with cancer, this aspect of competition for FcγR engagement should be more widely explored.

While our data agrees with the concept that targeting OX40 and particularly the combination with checkpoint blockade could be a therapeutic option, clearly more is still needed for this to be translated successfully to the clinic. A greater understanding of what is needed for OX40 therapies to work in preclinical models and the difference between those models where treatment fails or succeeds, may provide the insight to deliver favorable outcome in patients. Similarly, lessons from the clinic in terms of FcγR profiles, cellular compositions and spatial arrangements in conjunction with biomarkers for underpinning immune mechanisms, in relation to varying doses, will help inform how to develop more effective strategies targeting OX40 in the future.

Material and methods

Primary human samples

hPBMCs were obtained from whole blood following centrifugation through a density gradient medium. Patient with surgically resected cancer tumor tissues were obtained from Avaden Biosciences (Seattle), shipped overnight. Fresh tumors were dissociated immediately on arrival, and within 24 hours of surgical resection using GentleMacs Human Tumor Dissociation kit (Miltenyi Cat. #130-095-929). Baseline immune phenotyping occurred immediately on tumor dissociation.

Mice

C57BL/6, BALB/C and OT-I mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories or Envigo. hOX40KI were generated by Ozgene.16 hOX40KI/OT-I mice were generated in house. Young adult mice were sex-matched and age-matched and randomly assigned to experimental groups. Experiments were not blinded.

Antibody production

Anti-hOX40 mAb was produced as previously described.13 Isotype switching was performed by cloning V regions into mammalian expression vectors encoding mIgG1, mIgG2a, hIgG1, hIgG2 or hIgG4 (S228P L235E to minimize hIgG4 Fab arm exchange) constant regions. Antibodies were expressed by transient transfection of HEK293 cells and purified from supernatants by protein A affinity chromatography using MabSelect SuRe columns (GE HealthCare) followed by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) using Superdex 26/60,200 SEC columns (GE HealthCare). All preparations were filter sterilized (0.2 µM) and endotoxin low (<2 EU/mg protein).

ADCC reporter assays

PBMCs from healthy human donors were cultured for 42 hours±human T activator CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Gibco). CD4+T effector and Treg cells were isolated with the EasySep Human CD4+CD127lowCD25+Regulatory T cell Isolation kit (STEMCELL) and CD8 T cells with Dynabeads CD8 Positive Isolation Kit (Invitrogen). These cells were treated with anti-hOX40 antibodies or isotype controls and used as targets in the ADCC Reporter Bioassay kit (Promega) at a 1:6 ratio, incubated at 37°C for 6 hours. Luminescence was read using an Envision plate reader.

OX40 receptor density determination

Quantification of OX40 levels was assessed using PE-labeled GSK3174998 with BD Quantibrite beads (BD Biosciences) via flow cytometry. Spearman correlation coefficients and two-tailed t-tests were calculated in GraphPad Prism using the total OX40 receptor values and the fold induction obtained for each cell type.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry antibodies are listed in table 1. Intracellular staining was performed using Foxp3 staining buffer kit (Thermo Fisher-eBioscience) or Transcription Factor Buffer set (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All flow cytometry experiments were performed on either an FACSCanto II or Fortessa (BD Bioscience). Data analyzed using FACSDiva (BD Bioscience) or FlowJo (BD Bioscience).

Table 1.

Flow cytometry antibodies used

| Target | Clone | Company |

| mCD8a | 53–6.7 | Thermo Fisher-eBioscience |

| mCD4 | GK1.5 | Thermo Fisher-eBioscience |

| mCD3 | 145–2 C11 | Thermo Fisher-eBioscience |

| mFoxp3 | FJK-16s | Thermo Fisher-eBioscience |

| mCD62L | MEL-14 | Thermo Fisher-eBioscience |

| mCD44 | IM7 | Thermo Fisher-eBioscience |

| H-2Kb/SIINFEKL tetramer | Southampton University | |

| isotypes | Corresponding companies | |

| hCD4 | RPA-T4 | BD-Biosciences |

| hCD8 | RPA-T8 | BioLegend |

| hFoxP3 | PCH101 | eBioscience |

| hCD25 | BC96 | BioLegend |

| hOX40 | ACT-35 | eBioscience |

OT-I adoptive transfer

1×105 hOX40 KI+/– OT-I cells were injected intravenous into hOX40 KI+/+ or WT C57BL/6 mice. 24 hours later 5 mg ovalbumin (Sigma) and 100 µg anti-hOX40 or isotype control were given intraperitoneal (i.p.) splenic analysis was performed by harvesting spleens on day 4 post i.p. OT-I kinetics were monitored in the blood through SIINFEKL tetramer staining and mice were rechallenged 6–10 weeks later with 30 nM SIINFEKL (Peptide Synthetics) intravenous once the memory T-cell population had contracted to less than 1% of the single cell population. Mice with SIINFEKL tetramer responses <1% of CD8+lymphocytes at the peak of the response were excluded due to the likelihood that OT-I transfer had failed since isotype controls peak at an average 5.2%±0.58 SEM (mIgG1) and 4.65%±0.65 SEM (mIgG2a) in blood and 3.8%±0.79 SEM (mIgG1) and 3.1%±0.89 on day 4 in spleens. Exclusions based on these criteria are indicated in figure legends.

Tumor models

CT26: 5×104 CT26 (ATCC: CRL-2638) mouse colon carcinoma cells were inoculated subcutaneously into the flank of BALB/C mice. Palpable tumors were measured using calipers with tumor volume calculated using (L×W×H)/2 or 0.52×length×width2. Mice (n=7–13/treatment group) were randomized when tumors reached approximately 100–150 mm3 and treated with anti-mOX40 rat (r)IgG1 (clone OX86, Bio X Cell BE0031), anti-mPD-1 rIgG2a (clone RPM1-14, Bio X Cell BE0146) or their respective isotype controls, rIgG1 (clone HRPN, Bio X Cell BE0088) or rIgG2a (clone 2A3, Bio X Cell BE0089). Antibodies were given i.p. twice/week starting on randomization day for a total of six doses for efficacy studies or up to three doses for pharmacodynamic studies. In combination experiments with CT26, antibodies were dosed concurrently. Mice were removed from the study when maximal tumor size was reached (either 2,000 or 4,000 mm3, depending on the study site). Mice were also removed due to weight loss (>20%), ulceration or tumor necrosis, or any obvious inhibition of normal mouse activity.

E.G7-OVA: 5×105 E.G7-OVA cells were injected subcutaneously into the flank of hOX40KI+/+ mice. Based on preliminary experiments n=5 was determined as sufficient to see a p<0.05 for tumor therapy. Groups of eight mice were inoculated to ensure a minimum of 5/group with established tumors with comparable size (between 5×5 and 8×8 mm) for treatment. Mice were then ranked according to tumor size and assigned to treatments groups so that average tumor size per group was equivalent. This ensured mixed treatment groups within cages to reduce the influence of housing on treatment effect. Mice received 3×100 µg anti-hOX40 mAb or isotype i.p. every third day. Mice were culled once they reached humane endpoint (20×20 mm) or end of experiment if long-term survivors. Mice which eradicated tumor after treatment were rechallenged with 5×105 E.G7-OVA S.C. into the flank. Combination experiments of anti-OX40 hIgG1 (100 µg) and anti-PD-1 rIgG2a (250 µg; clone RPM1-14, Bio X Cell BE0146) were performed as outlined in figure 5F.

Pharmacodynamic studies

Mouse pharmacodynamic studies were performed in A20 or CT26 mouse models following monotherapy or combination treatment. In monotherapy studies, animals were dosed with 100 µg rIgG1 or anti-mOX40 rIgG1 (OX86) once or twice a week and harvested 48 hours following the third dose. In combination studies, mice were randomized into five groups receiving vehicle, isotype control (rIgG1 100 µg+rIgG2 a 200 µg), anti-mOX40 (OX86 100 µg+rIgG2 a 200 µg), anti-PD-1 (PD-1 200 µg+rIgG1 100 µg) or anti-mOX40 and anti-PD-1 (OX86 100 µg+PD-1 200 µg). Mice were dosed twice a week on days 0, 3 and 7 and blood and tumor harvested on days 3, 7 and 10 following the first dose equating to one, two and three doses, respectively. Tumor samples collected were subjected to dissociation using Miltenyi Tumor Dissociation Kit cocktail (Miltenyi Biotec, Cat#130-096-730) for 40 min at 37°C. After digestion and filtration, 1×105 cells were pre-blocked where necessary with human or mouse Fc block (Miltenyi Biotec) and stained with detection antibodies.

Statistics

All results show mean±SEM. One-way analysis of variance with multiple comparisons (Dunnett’s, Tukey’s or Sidak’s as stated in legend) or Mann-Whitney tests were used as stated in legends, performed using GraphPad Prism. Survival curves were evaluated using a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Significance shown relative to isotype control unless bar is shown. Where indicated ns=not significant, *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001, ****p≤0.0001.

jitc-2023-008677supp001.pdf (140.6KB, pdf)

Footnotes

@LauraBover52969

NY and MSC contributed equally.

Contributors: JEW, LD, KLC, TM, SB, HJ, DK, HS, PB, JJ, LB, KSV and LS-W performed experiments. JEW, LD, SB, HJ, DK, HS, PB, JJ, LB, KV and LS-W performed statistical analyses. MJ, VE, TI, CAP, HN, AJS, SH, and LH provided technical support, reagent generation and QC. JEW, LD, SB, HJ, DK, HS, PB, JJ, LS-W, PJM, SJB, NY and MSC designed experiments. JEW, RS, JS, AH, EP, SLM, SJB, PJM, NY and MSC provided concept leadership. JEW, PJM, NY and MSC wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and read and approved the submitted version. MSC acts as guarantor for the content.

Competing interests: MSC is a retained consultant for BioInvent International and has performed educational and advisory roles for Baxalta and Boehringer Ingelheim. He has consulted for GSK, Radiant, iTeos Therapeutics, Surrozen, Hanall and Mestag and received research funding from BioInvent, Surrozen, GSK, UCB and iTeos. SB, HJ, LS-W, DK, HS, PB, JJ, HN, AJS, LH, SH, SJB, RS, JS, AH, EP, SLM, PJM and NY are (or were at the time the work was conducted) employees of GSK.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Human biological samples were sourced ethically and used in accordance with informed consent. Patient material was obtained with the appropriate informed consent in accordance with the GSK human biological sample management policy and standard operating procedure. Healthy blood for PBMC obtained from GSK: Quorum (Advarra) Protocol #24109QMR/3. Tumor samples for the TILS were bought from Avaden Bio . Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer Immunotherapy Science 2013;342:1432–3. 10.1126/science.342.6165.1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer Immunotherapy using Checkpoint blockade. Science 2018;359:1350–5. 10.1126/science.aar4060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kalbasi A, Ribas A. Tumour-intrinsic resistance to immune Checkpoint blockade. Nat Rev Immunol 2020;20:25–39. 10.1038/s41577-019-0218-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kubli SP, Berger T, Araujo DV, et al. Beyond immune Checkpoint blockade: emerging immunological strategies. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021;20:899–919. 10.1038/s41573-021-00155-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sharma P, Hu-Lieskovan S, Wargo JA, et al. Primary, adaptive, and acquired resistance to cancer Immunotherapy. Cell 2017;168:707–23. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alves Costa Silva C, Facchinetti F, Routy B, et al. New pathways in immune stimulation: targeting Ox40. ESMO Open 2020;5:e000573. 10.1136/esmoopen-2019-000573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aspeslagh S, Postel-Vinay S, Rusakiewicz S, et al. Rationale for anti-Ox40 cancer Immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer 2016;52:50–66. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deng J, Zhao S, Zhang X, et al. Ox40 (Cd134) and Ox40 ligand, important immune checkpoints in cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2019;12:7347–53. 10.2147/OTT.S214211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buchan SL, Rogel A, Al-Shamkhani A. The Immunobiology of Cd27 and Ox40 and their potential as targets for cancer Immunotherapy. Blood 2018;131:39–48. 10.1182/blood-2017-07-741025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weinberg AD, Morris NP, Kovacsovics-Bankowski M, et al. Science gone Translational: the Ox40 agonist story. Immunol Rev 2011;244:218–31. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01069.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rogers PR, Song J, Gramaglia I, et al. Ox40 promotes bcl-xL and Bcl-2 expression and is essential for long-term survival of Cd4 T cells. Immunity 2001;15:445–55. 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00191-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Song J, So T, Cheng M, et al. Sustained Survivin expression from Ox40 Costimulatory signals drives T cell Clonal expansion. Immunity 2005;22:621–31. 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Voo KS, Bover L, Harline ML, et al. Antibodies targeting human Ox40 expand Effector T cells and block inducible and natural regulatory T cell function. J Immunol 2013;191:3641–50. 10.4049/jimmunol.1202752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Willoughby J, Griffiths J, Tews I, et al. Ox40: structure and function - what questions remain. Mol Immunol 2017;83:13–22. 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gough MJ, Ruby CE, Redmond WL, et al. Ox40 agonist therapy enhances Cd8 infiltration and decreases immune suppression in the tumor. Cancer Res 2008;68:5206–15. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Griffiths J, Hussain K, Smith HL, et al. Domain binding and Isotype dictate the activity of anti-human Ox40 antibodies. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e001557. 10.1136/jitc-2020-001557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jensen SM, Maston LD, Gough MJ, et al. Signaling through Ox40 enhances antitumor immunity. Semin Oncol 2010;37:524–32. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Linch SN, McNamara MJ, Redmond WL. Ox40 agonists and combination Immunotherapy: putting the pedal to the metal. Front Oncol 2015;5:34. 10.3389/fonc.2015.00034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Turaj AH, Cox KL, Penfold CA, et al. Augmentation of Cd134 (Ox40)-Dependent NK anti-tumour activity is dependent on antibody cross-linking. Sci Rep 2018;8:2278. 10.1038/s41598-018-20656-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yadav R, Redmond WL. Current clinical trial landscape of Ox40 agonists. Curr Oncol Rep 2022;24:951–60. 10.1007/s11912-022-01265-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gutierrez M, Moreno V, Heinhuis KM, et al. Ox40 agonist BMS-986178 alone or in combination with Nivolumab and/or Ipilimumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27:460–72. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ma Y, Li J, Wang H, et al. Combination of PD-1 inhibitor and Ox40 agonist induces tumor rejection and immune memory in Mouse models of Pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology 2020;159:306–19. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Messenheimer DJ, Jensen SM, Afentoulis ME, et al. Timing of PD-1 blockade is critical to effective combination Immunotherapy with anti-Ox40. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:6165–77. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shrimali RK, Ahmad S, Verma V, et al. Concurrent PD-1 blockade negates the effects of Ox40 agonist antibody in combination Immunotherapy through inducing T-cell apoptosis. Cancer Immunol Res 2017;5:755–66. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang R, Gao C, Raymond M, et al. An integrative approach to inform optimal administration of Ox40 agonist antibodies in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:6709–20. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Postel-Vinay S, Lam VK, Ros W, et al. First-in-human phase I study of the Ox40 agonist Gsk3174998 with or without Pembrolizumab in patients with selected advanced solid tumors (ENGAGE-1). J Immunother Cancer 2023;11:e005301. 10.1136/jitc-2022-005301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bulliard Y, Jolicoeur R, Zhang J, et al. Ox40 engagement depletes Intratumoral Tregs via activating Fcgammars, leading to antitumor efficacy. Immunol Cell Biol 2014;92:475–80. 10.1038/icb.2014.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Campos Carrascosa L, van Beek AA, de Ruiter V, et al. Fcgammariib engagement drives agonistic activity of FC-engineered Alphaox40 antibody to stimulate human tumor-infiltrating T cells. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8:e000816. 10.1136/jitc-2020-000816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dahan R, Sega E, Engelhardt J, et al. Fcgammars modulate the anti-tumor activity of antibodies targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis. Cancer Cell 2015;28:285–95. 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moreno-Vicente J, Willoughby JE, Taylor MC, et al. Fc-null anti-PD-1 Monoclonal antibodies deliver optimal Checkpoint blockade in diverse immune environments. J Immunother Cancer 2022;10:e003735. 10.1136/jitc-2021-003735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang T, Song X, Xu L, et al. The binding of an anti-PD-1 antibody to Fcgammariota has a profound impact on its biological functions. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2018;67:1079–90. 10.1007/s00262-018-2160-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Al‐Shamkhani A, Birkeland ML, Puklavec M, et al. Ox40 is Differentially expressed on activated rat and Mouse T cells and is the sole receptor for the Ox40 ligand. Eur J Immunol 1996;26:1695–9. 10.1002/eji.1830260805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chu F, Li HS, Liu X, et al. Cxcr5(+)Cd8(+) T cells are a distinct functional subset with an antitumor activity. Leukemia 2019;33:2640–53. 10.1038/s41375-019-0464-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Polesso F, Weinberg AD, Moran AE. Late-stage tumor regression after PD-L1 blockade plus a concurrent Ox40 agonist. Cancer Immunol Res 2019;7:269–81. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jackson H, Bhattacharya S, Bojczuk P, et al. 1192P - evaluation of Ox40 receptor density, influence of IgG Isotype and dosing paradigm in anti-Ox40-mediated efficacy and biomarker responses with PD-1 blockade. Ann Oncol 2018;29:viii424–5. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stewart R, Hammond SA, Oberst M, et al. The role of FC gamma receptors in the activity of immunomodulatory antibodies for cancer. J Immunotherapy Cancer 2014;2:29. 10.1186/s40425-014-0029-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Temming AR, Bentlage AEH, de Taeye SW, et al. Cross-reactivity of Mouse IgG Subclasses to human FC gamma receptors: antibody Deglycosylation only eliminates Igg2B binding. Mol Immunol 2020;127:79–86. 10.1016/j.molimm.2020.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Beers SA, Glennie MJ, White AL. Influence of immunoglobulin Isotype on therapeutic antibody function. Blood 2016;127:1097–101. 10.1182/blood-2015-09-625343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Buchan SL, Dou L, Remer M, et al. Antibodies to Costimulatory receptor 4-1Bb enhance anti-tumor immunity via T regulatory cell depletion and promotion of Cd8 T cell Effector function. Immunity 2018;49:958–70. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Li F, Ravetch JV. A general requirement for Fcgammariib Co-engagement of agonistic anti-TNFR antibodies. Cell Cycle 2012;11:3343–4. 10.4161/cc.21842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. White AL, Chan HTC, French RR, et al. Fcgammariotaiotab controls the potency of agonistic anti-TNFR mAbs. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2013;62:941–8. 10.1007/s00262-013-1398-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beers SA, French RR, Chan HTC, et al. Antigenic modulation limits the efficacy of anti-Cd20 antibodies: implications for antibody selection. Blood 2010;115:5191–201. 10.1182/blood-2010-01-263533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Divergent immunoglobulin G Subclass activity through selective FC receptor binding. Science 2005;310:1510–2. 10.1126/science.1118948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Verma V, Shrimali RK, Ahmad S, et al. PD-1 blockade in Subprimed Cd8 cells induces dysfunctional PD-1(+)Cd38(Hi) cells and anti-PD-1 resistance. Nat Immunol 2019;20:1231–43. 10.1038/s41590-019-0441-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Arce Vargas F, Furness AJS, Litchfield K, et al. Fc Effector function contributes to the activity of human anti-CTLA-4 antibodies. Cancer Cell 2018;33:649–63. 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Freeman ZT, Nirschl TR, Hovelson DH, et al. A conserved Intratumoral regulatory T cell signature identifies 4-1Bb as a pan-cancer target. J Clin Invest 2020;130:1405–16. 10.1172/JCI128672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Montler R, Bell RB, Thalhofer C, et al. Ox40, PD-1 and CTLA-4 are selectively expressed on tumor-infiltrating T cells in head and neck cancer. Clin Transl Immunology 2016;5:e70. 10.1038/cti.2016.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wasiuk A, Testa J, Weidlick J, et al. Cd27-mediated regulatory T cell depletion and Effector T cell Costimulation both contribute to antitumor efficacy. J Immunol 2017;199:4110–23. 10.4049/jimmunol.1700606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hussain K, Hargreaves CE, Roghanian A, et al. Upregulation of Fcgammariib on monocytes is necessary to promote the Superagonist activity of Tgn1412. Blood 2015;125:102–10. 10.1182/blood-2014-08-593061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. White AL, Chan HTC, Roghanian A, et al. Interaction with Fcgammariib is critical for the agonistic activity of anti-Cd40 Monoclonal antibody. J Immunol 2011;187:1754–63. 10.4049/jimmunol.1101135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bruhns P, Jönsson F. Mouse and human FCR Effector functions. Immunol Rev 2015;268:25–51. 10.1111/imr.12350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dekkers G, Bentlage AEH, Stegmann TC, et al. Affinity of human IgG Subclasses to Mouse FC gamma receptors. MAbs 2017;9:767–73. 10.1080/19420862.2017.1323159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chan FK, Chun HJ, Zheng L, et al. A domain in TNF receptors that mediates ligand-independent receptor assembly and signaling. Science 2000;288:2351–4. 10.1126/science.288.5475.2351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Waight JD, Chand D, Dietrich S, et al. Selective Fcgammar Co-engagement on Apcs modulates the activity of therapeutic antibodies targeting T cell antigens. Cancer Cell 2018;33:1033–47. 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yofe I, Landsberger T, Yalin A, et al. Anti-CTLA-4 antibodies drive myeloid activation and Reprogram the tumor Microenvironment through Fcgammar engagement and type I interferon signaling. Nat Cancer 2022;3:1336–50. 10.1038/s43018-022-00447-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lim SH, Beers SA, Al-Shamkhani A, et al. Agonist antibodies for cancer Immunotherapy: history, hopes and challenges. Clin Cancer Res 2024;30:1712–23. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-23-1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Orr CM, Fisher H, Yu X, et al. Hinge Disulfides in human Igg2 Cd40 antibodies modulate receptor signaling by regulation of conformation and flexibility. Sci Immunol 2022;7. 10.1126/sciimmunol.abm3723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yu X, James S, Felce JH, et al. TNF receptor agonists induce distinct receptor clusters to mediate differential agonistic activity. Commun Biol 2021;4:772. 10.1038/s42003-021-02309-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Davis EJ, Martin-Liberal J, Kristeleit R, et al. First-in-human phase I/II, open-label study of the anti-Ox40 agonist Incagn01949 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer 2022;10:e004235. 10.1136/jitc-2021-004235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Diab A, Hamid O, Thompson JA, et al. Dose-escalation study of the Ox40 agonist Ivuxolimab in patients with locally advanced or metastatic cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2022;28:71–83. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-0845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kim TW, Burris HA, de Miguel Luken MJ, et al. First-in-human phase I study of the Ox40 agonist Moxr0916 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2022;28:3452–63. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-4020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hussain K, Liu R, Smith RCG, et al. HIF activation enhances Fcgammariib expression on mononuclear phagocytes impeding tumor targeting antibody Immunotherapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2022;41:131. 10.1186/s13046-022-02294-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Dees S, Ganesan R, Singh S, et al. Regulatory T cell targeting in cancer: emerging strategies in Immunotherapy. Eur J Immunol 2021;51:280–91. 10.1002/eji.202048992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sharma A, Subudhi SK, Blando J, et al. Anti-CTLA-4 Immunotherapy does not deplete Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells (Tregs) in human cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:1233–8. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Quezada SA, Peggs KS. Lost in translation: Deciphering the mechanism of action of anti-human CTLA-4. Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:1130–2. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liu R, Oldham RJ, Teal E, et al. Fc-engineering for modulated Effector functions-improving antibodies for cancer treatment. Antibodies (Basel) 2020;9:64. 10.3390/antib9040064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2023-008677supp002.pdf (446.9KB, pdf)

jitc-2023-008677supp001.pdf (140.6KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.