BACKGROUND

Traditionally, bedside teaching in the emergency department (ED) begins with determining the learners’ current skill level and establishing on‐shift goals. 1 , 2 , 3 Faculty commonly begin by asking, “What would you like to work on today?” 3 , 4 This method aids in goal setting and initiating conversations with educators but takes a problem‐solving approach and promotes identification of weaknesses. 4 This negatively frames the learning process and requires a high level of self‐reflection and vulnerability. Additionally, high‐achieving learners without significant deficits may benefit less.

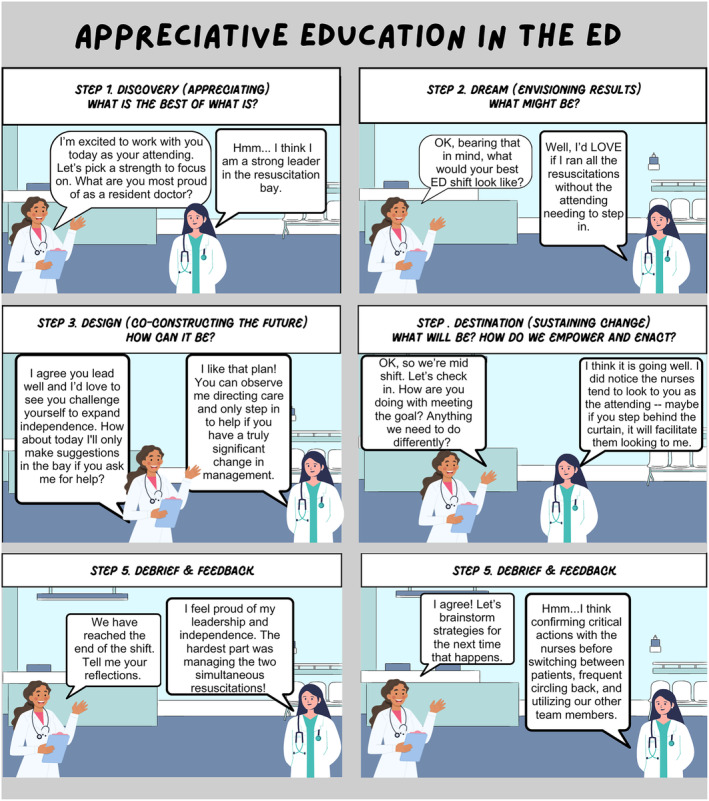

Appreciative inquiry (AI) provides an alternative framework frequently described in business literature. This model focuses on strengths to achieve an individual's or organization's full potential. 5 AI delineates four phases of inquiry, including discovery (What is the best of what is?); dream (What might be?); design (How can it be?); and destination (What will be? How can we empower and enact?). 6

Appreciative education (AE) utilizes AI in an educational context to focus on a learner's strengths and potential to accomplish cocreated goals. 7 Practical tips for applying AE principles to interactions with learners are to identify a clear outcome focus for a situation and to leverage the learner's strengths to achieve the desired outcome. 7 Use of AE in clinical teaching may enhance targeted feedback, improve learner motivation, and create a more positive learning environment.

EXPLANATION

A cohort of faculty at our academic 4‐year emergency medicine (EM) residency program reviewed an article on AE during a faculty development session and brainstormed how to apply it during subsequent ED shifts with EM trainees and medical students. 5 Thereafter, the cohort of faculty began each shift by identifying the learners’ outcomes, asking about their current strengths, and the characteristics of their ideal ED shift. Faculty and learners then collaboratively brainstormed concrete ways to achieve those outcomes. Throughout the shift faculty reflect with the learner on progress with their goals and problem solve barriers. The shift concludes with a reflection and debrief. Figure 1 depicts the technique. After a month of implementation, the faculty cohort met to discuss their experiences.

FIGURE 1.

Demonstration of AI by an attending and resident in the ED. AI, appreciative inquiry.

DESCRIPTION

Experience utilizing AE in conjunction with informal feedback from learners has provided insight into the benefits and pitfalls of this teaching strategy. Witnessed benefits include improved learner motivation and self‐esteem. 7 Learners self‐reported having a positive reaction to the initial prompt encouraging reflection about strengths and they enjoyed envisioning an ideal shift. AE especially benefited high‐achieving learners who felt challenged and motivated by the exercise. It enhanced the perceived quality of feedback given by faculty.

Pitfalls of AE include that the onus is on the faculty member to keep the learner accountable with their goals. The unpredictable nature of the ED environment can complicate this technique given the lack of control over aspects of the shift that would make it “ideal”; however, the act of visioning and focusing on modifiable factors can allow both parties to feel empowered and have a sense of control despite common inherent challenges (i.e., boarding, frequent interruptions, challenging consultant interactions). Future steps include formal multi‐institutional study of this technique.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Schnabel NE, Okoli DK, Bailes CA, Davis MG, Haas MRC. Appreciative education to improve teaching interactions in the emergency department. AEM Educ Train. 2024;8:e11010. doi: 10.1002/aet2.11010

Supervising Editor: Jeffrey N Siegelman

REFERENCES

- 1. Irby DM, Bowen JL. Time‐efficient strategies for learning and performance. Clin Teach. 2004;1(1):23‐28. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Natesan S, Bailitz J, King A, et al. Clinical teaching: an evidence‐based guide to best practices from the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(4):985‐998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khamees D, Wolff M. No time, no room: on‐shift teaching for any shift. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5(4):e10701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fazzio P, Hardy E, Chamberlain M, et al. “What do you want to learn or work on today?”: benefits and barriers to asking residents for self‐identified learning goals. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5(3):e10564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sandars J, Murdoch‐Eaton D. Appreciative inquiry in medical education. Med Teach. 2017;39(2):123‐127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cooperrider DL, Whitney D, Stavros JM. Application of the 4‐D cycle of appreciative inquiry. Appreciative Inquiry Handbook: For Leaders of Change. Crown Custom Publications; 2008:103‐199. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bloom JL, Hutson BL, He Y, Konkle E. Appreciative education. New Dir Stud Serv. 2013;2013(143):5‐18. [Google Scholar]