Dutch GPs are being advised by their own professional body not to prescribe a new low dose, monophasic oral contraceptive, marketed under the trade name Yasmin, until studies have established whether it is as safe as other contraceptive pills.

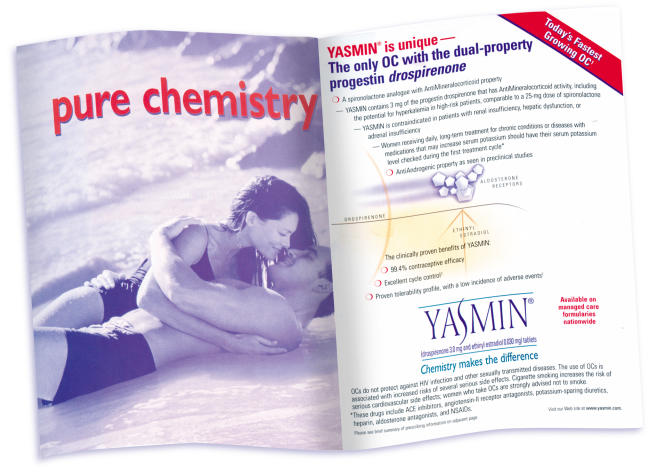

The new contraceptive, which is a combination of drospirenone (a progestogen) and ethinylestradiol, has been available in several European countries since 2000 and was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration last May. It is licensed for use in the United Kingdom, where it is being launched next week.

Last year a 17 year old Dutch girl who had been taking Yasmin died from a venous thrombosis. Although no direct link with Yasmin has ever been shown, 40 cases of venous thrombosis among women taking Yasmin, two of which were fatal, have now been reported in Europe.

The Dutch College of General Practitioners has now reiterated its position that GPs should continue to choose the second generation pill, because of the lack of epidemiological data on the risk of thrombosis from Yasmin.

The Dutch Medicines Evaluation Agency, which has a leading role in the European Union in assessing the safety of Yasmin, has as a result of the two deaths asked that the drug carry a warning that the risk of venous thrombosis from using it remains unknown. Before licensing Yasmin the agency had also asked for more research into side effects and coagulation. Final results from a comparative study over three years involving 3000 women have yet to be published.

The agency said: “The impression exists that GPs are inclined to prescribe the new pill earlier in the assumption that the risk of venous thrombosis is smaller than with the second and third generation of contraceptive pill,” but added that this cannot be concluded from the available data.

Speaking on a Dutch radio station, Frits Rosendaal, professor of clinical epidemiology at Leiden University Medical Centre, called for GPs not to prescribe Yasmin until the risk of venous thrombosis was known.

He said: “I am not satisfied it is absolutely safe.” He was alarmed that as many as 40 cases have been reported voluntarily by doctors so soon after Yasmin was registered. “Doctors seem to believe it is safer, but we don't know. We are making the same mistake as with the third generation contraceptive pill.”

Yasmin's manufacturer, the German pharmaceutical company Schering, is “absolutely convinced of the safety of Yasmin.” It has written to all Dutch GPs, gynaecologists, and pharmacists, saying that the 40 reported cases of venous thrombosis among a million users of Yasmin, mainly in Europe, do “absolutely not indicate an increased risk of venous thrombosis.”

A Schering senior medical adviser, Dr Egbert Klaassen, said the company had conducted all the necessary research acceptable to the Medicines Evaluation Agency and the FDA. Interim results from Schering's post-marketing surveillance study of a million cycles show that, after one year, one venous thrombosis occurred among Yasmin users, compared with five among users of other oral contraceptives.

Yasmin has been licensed in Europe since November 2000. Schering estimates that about 35000 women are using it in the Netherlands and 500000 throughout 17 countries in Europe.