Religion used to define morally acceptable conduct, then doctors became interested in sexual behaviour. Now we live in a world where celibacy is the new deviance, and surgery and drugs are used to enhance sexual pleasure. Graham Hart and Kaye Wellings reflect on the extent and consequences of the medicalisation of sexual behaviour

“Sex survey ruined our wedding,” screamed the front page of the Sun.1 The newspaper reported how a “couple had a furious row and called off their wedding after the bride-to-be revealed their sex secrets in a university survey.” This could be a routine example of how the press uses research on sex to sell papers. This case is more interesting, however, because the groom to be was clearly unhappy with the extent of sexual surveillance, which arguably is a feature of the medicalisation of sexual behaviour in British society. To what extent has there been a medicalisation of sex, and what are the consequences of this?

Summary points

Medical authority over sexual behaviour has a long history

In the 19th century, labels distinguished “perversions” from “acceptable behaviour,” and some doctors invented adverse outcomes of sexual acts to deter the practice of these acts

In the 20th century, disorders previously seen as morally inadmissible became “treatable”

The late 20th century saw major changes in sexual attitudes and mores as therapeutic advances removed adverse outcomes of sexual behaviour

Our obsession with sexual gratification increases expectations and feelings of inadequacy

The medicalisation of sex has resulted in surgery and drugs being used to enhance sexual pleasure

Overly medical approaches to sex ignore the social and interpersonal dynamics of relationships

Medical authority and sexual behaviour

The exercise of medical authority over sexual behaviour has a long history. Religion once defined morally acceptable sexual conduct, but in an increasingly secular society, this task fell to medical science. In the latter half of the 19thcentury, medical professionals became interested in behavioural domains previously the preserve of religious authorities and moralists—criminality, alcohol and drugs, and sex.2–4 Although Philip Larkin would have us believe that “sexual intercourse began in nineteen sixty-three,”5 the taxonomy by which sexual behaviour is defined was invented a century earlier, when a new breed of sexologists created diagnostic categories such as homosexual and heterosexual, hysteria and nymphomania, and a host of arcane paraphilias.6 These labels served to define what was normal and acceptable and what was not, distinguishing “perversions” from “acceptable” heterosexual, procreative, and monogamous sex.

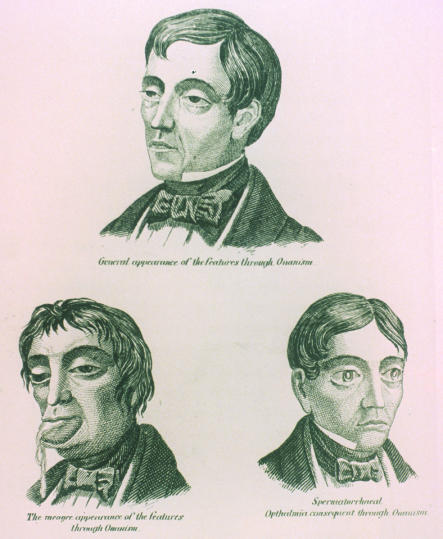

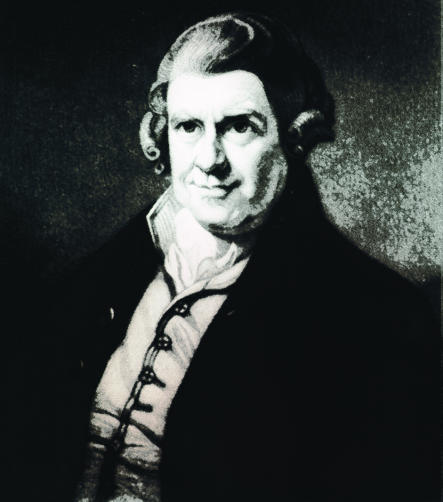

The long tradition of representing illness as a punishment for sin was continued when sexual behaviour was medicalised and transformed into morbidity.7 Some doctors described in detail the supposed adverse outcomes of sexual acts to deter the practice of these acts (figs 1 and 2). In the mid-19th century, William Acton prescribed against masturbation (fig 3). He invented a condition that he called “spermatorrhoea” (box B1), which left generations of boys and young men with the injunction that manly youth “should be accompanied by complete repose of the generative [sexual] functions, unbroken by anything like intense feeling for their employment.”8

Figure 1.

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

Facial effects of masturbation. From Boyhood's perils and manhood's curse, 1858

Figure 2.

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

Device to discourage masturbation. From Considération sur les hernies, Paris

Figure 3.

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

William Acton, 1813-1875

Box 1.

Symptoms of spermatorrhoea

- Nocturnal emissions

- Loss of sperm during urination

- Inaptitude for work

- Disinclination for sexual intercourse

- General debilitation

- Impotence

Doctors and discussion of sexual behaviour

Acton was a doctor and could be explicit about sexual behaviour, but by daring to pay any attention to sex, he was rare in the profession.9 Others, such as Havelock Ellis—also medically qualified10—followed, but the open discussion of sexuality and sexual behaviour in Britain in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was led not by “medical men” but by other liberal intellectuals. These included Edward Carpenter—socialist writer and admirer of muscular working men6—and Marie Stopes—the great publicist for contraception (for married women) and writer on sex (in marriage)—who was a botanist.10 Alfred Kinsey—the American expert on sexual behaviour in the 1940s and '50s—trained as an entomologist.

Until the mid-20th century, the number of doctors who wrote about sex was small.11 The fact that few medically qualified doctors provided historical accounts of sexual behaviour does not mean, however, that medicalisation had not occurred. If medicalisation is seen as a social process that does not require the active involvement of doctors, and medical science is invoked to support particular ideological positions, then the medicalisation thesis can be sustained regardless of the number of doctors involved.

Psychiatry and the medicalisation of sex

Psychiatry, as the moral arm of medicine, played a major role in developing the idea that some sexual behaviours are expressions of disease. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, first published by the American Psychiatric Society in 1952, described “treatable” behaviours that previously had been seen as morally inadmissible. This book was hugely influential in defining and sustaining judgments regarding the sexual behaviours that required medical intervention.12 For example, homosexuals, formerly considered to be sinners, were labelled as ill—not bad, but mad. Commitments to mental institutions, hormonal treatments, and castrations were used to deal with unwanted sexual behaviour. This process has taken a new form recently, with the search for the “gay gene” and the continuing refusal of some to see sexual expression as historically variable and socially constructed.13,16

In the years before the second world war, pregnant, unmarried young women could still be sent to and indefinitely detained in psychiatric institutions. Treatments for homosexual men—such as aversion therapy—continued until, and beyond, 1973, when the American Psychiatric Association redesignated homosexuality as non-pathological. Even venereology (later genitourinary medicine)—the specialty specifically responsible for treating sexually transmitted infections—was marked throughout the 20th century by an uneasy truce between medical moralists and those promoting practical public health measures to prevent infection.14 R C L Batchelor, Physician in Charge of Edinburgh's venereal disease services until 1954, often described people who transmitted infections as “moral defectives” who should be confined.15

Men, women, and sexual behaviour

A marked distinction has existed with respect to the perceived responsibility of men and women for sexual health—women consistently have been seen as “reservoirs of infection.” In 1962, health promotion materials that targeted men could say that “a girl may be perfectly clean . . . and yet have in her body millions of the invisible germs of gonorrhoea or syphilis, or perhaps both.”15 Even in the late 20th century, the United Kingdom's proposed national screening programme for Chlamydia trachomatis suggested that only women be tested.16

A new era for sexual attitudes

The latter half of the 20th century saw major changes in sexual attitudes and mores. We no longer look on sex not for procreation as sinful. This change in attitude has been accompanied by greater acceptance of the diversity of human relations. The shift in perspective has been dramatic, and it means that variations within and between heterosexual and homosexual desire have become—to a greater extent than ever before—a matter of choice. For some religious stalwarts, sex is still acceptable only as a procreative activity within marriage; for others, it's OK to be homosexual but not to practise same sex activities. Generally, however, people increasingly accept diverse sexual expression.17

The trend towards accepting that sexual congress is not exclusively for reproduction, but is part of healthy human interactions and relations has, with a few exceptions and provisos, been furthered by the medical profession. Therapeutic discoveries have removed many of the adverse outcomes of sexual behaviour. Medical treatments and interventions have saved thousands of lives and prevented significant morbidity resulting from sexual behaviour:

Antibiotics for bacterial infections

Vaccination to prevent viral infections

Antiviral and antiretroviral treatments for herpes simplex virus-2 and HIV.

The development of the contraceptive pill freed women from the fear and reality of unwanted pregnancies, despite its side effects. Marks—in her history of the pill—refers to women for whom this was “a dream come true.”18 Even critics of the pill cannot deny the massive social changes intimately connected with the widespread availability in the late 20th century of this chemically based contraception for women.

Mass surveillance, regulation, and control

The philosopher Michel Foucault and his followers warned that liberalisation of sex, open discussion about sex, and more importantly the detailed scientific description of its parameters and correlates may just be part of a continuing modern project of regulation and control.19 According to this view, various works across the years have simply been ever more rigorous and systematic variations of the surveillance of sexual behaviour by the state and other disciplinary institutions (box B2). For followers of Foucault, the “clinical gaze” (a generally medicalised perspective on the world) transforms this surveillance into control over sexuality, both in the population—through public health mechanisms—and (ideally) through self regulation.

Box 2.

Studies of sexual behaviour

Mass surveillance inadvertently establishes norms and standards for sexual behaviour against which people can measure themselves and be measured. This can bring benefits—when Kinsey reported on the heterogeneity of sexual conduct in America,20,21 Americans who had previously felt deviant gave a collective sigh of relief. There are also risks attached to such transparency—many people will feel “inadequate” when faced with evidence about extremes of sexual performance. This can turn sex into a problem—“Is that normal, doctor?” From identification of the average number of times Britons have sex every month (6.4 times for men and, interestingly, 6.5 for women)24 to articles in Cosmopolitan magazine on how to have better sex and achieve orgasms every time, the prescriptive boundaries of normality are pushed further, and imperatives are stated.

Medicalisation and sexual pleasure

Not surprisingly perhaps, the medicalisation of sexual behaviour has extended most recently into the domain of sexual pleasure. Doctors are wheeled in to place sex at the centre of a healthy lifestyle, and articles peppered with physiological and technical terms confirm and elaborate on the right way to perform “to please him or her.” Men and women are encouraged to protract their sexually active lives, regardless of desire. Viagra (sildenafil citrate)—the first oral drug to treat impotence, or erectile dysfunction—ranks as one of the greatest success stories in pharmaceutical history. When it was launched in 1998, it became the world's most popular medicinal drug ever, outselling even fluoxetine (Prozac). Although Viagra is not yet approved for women by the US Food and Drug Administration, studies are evaluating its effects in women with arousal problems.

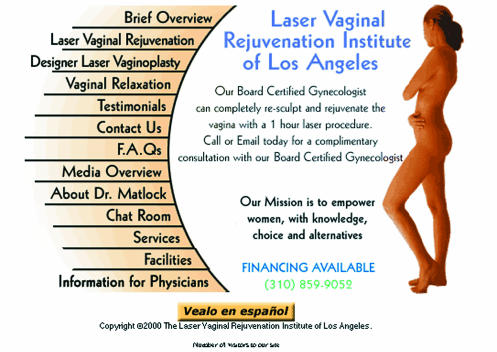

Gynaecological surgery is also being harnessed to enhance female sexual pleasure and improve aesthetics (fig 4). So far, genital enhancement—the so called “designer vagina”—has had little impact in the United Kingdom, but it is routinely advertised in America. Procedures include:

Figure 4.

Does such advertising encourage sexual dissatisfaction?

Liposuction of oversized vulvas

Labiaplasty to “aesthetically modify” the labia

Clitoral repositioning

Tightening of vaginal muscles and support tissues

Reduction by laser of redundant vaginal mucosa.

Some of these procedures grew out of traditional gynaecological surgery for urinary incontinence and episiotomies—the “extra stitch for the husband” familiar to gynaecologists. Laser pruning of unsightly or unsatisfying genital morphology is now carried out, however, expressly for sexual gratification.

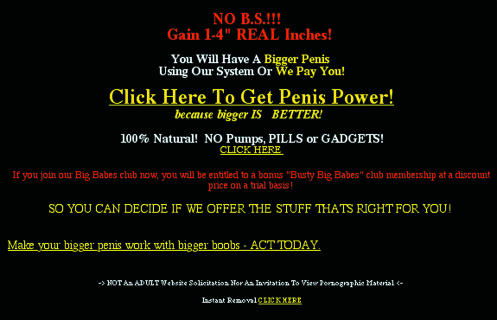

The application of medicine has considerable scope in this context (fig 5). In America, erectile dysfunction is estimated to affect 50% of men aged 40-70 and 70% of men >70 years.27,28 Thirty one per cent of American men and 43% of American women have reportedly had sexual dysfunction at some time in their lives.29 These estimates explain, in part, the stampede to obtain Viagra. Yet whether people seek medical treatment is associated not only with the scale of a problem, but also with its perceived severity and the opportunities for treatment. The high prevalence of sexual dysfunction reflects the escalating sexualisation of our culture—our obsession with sexual gratification has undoubtedly increased people's expectations, and it may have increased people's feelings of inadequacy. Although many men with erectile dysfunction daily thank Pfizer for their efforts, others who once thought their low libido was “normal” and acceptable now feel dissatisfied with their sexual lives.

Figure 5.

Furthering the “tyranny of genital sexuality”?

Overmedicalisation of sex

Relatively recently, the imperative was for restraint and moderation in sexual matters; now it is for more and better sexual gratification. We can see this as the replacement of one orthodoxy by another—as an over-medicalisation of sex. Celibacy is the new deviance. The irony is that we may be moving away from diversity towards greater uniformity. By encouraging women to look like Playboy centrefolds and men to seek priapic perfection, we may be furthering what has been termed the “tyranny of genital sexuality.”30

The authors of one American report on sexual dysfunction stated that “the strong association between sexual dysfunction and improved quality of life suggests that this problem [sexual dysfunction] warrants recognition as a serious public health concern.”29 Yet American studies also show that many people's experiences of sexual dysfunction are associated with unsatisfying personal experiences and relationships—the cause of sexual dysfunction in these cases is almost certainly bidirectional.

The problem with an overly medical approach to sexual behaviour is that social and interpersonal dynamics may be ignored. People choose one another for their uniqueness. The last century saw a considerable increase in acceptance of diversity of sexual expression—it would be a shame if this century saw diversity replaced by uniform expectations of performance and desire.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Caroline Allen, Ray Moynihan, Mark Petticrew, Richard Smith, Daniel Wight, and Sally Macintyre for comments on drafts of this paper.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Bolouri Y. Sex survey ruined our wedding. Sun 1996 Nov 14:1-2. (Scottish edition.)

- 2.Sim J. Medical power in prisons: the prison medical service in England 1774-1989. Milton Keynes: Open University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berridge V, Edwards G. Opium and the people: opiate use in nineteenth century England. London: Yale; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porter R, Hall LA. The facts of life: The creation of sexual knowledge in Britain, 1680-1950. London: Yale; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larkin P. Collected poems. London: Faber and Faber; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weeks J. Sexuality and its discontents: meanings, myths and modern sexualities. London: Routledge; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sigerist H. A history of medicine. New York: Oxford University Press; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acton W. The functions and disorders of the reproductive organs in youth, adult age and advanced life, considered in their physiological, social and psychological relations. London: Churchill; 1857. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall LA. The English have hot-water bottles: the morganatic marriage between the British medical profession and sexology since William Acton. In: Porter R, Teich M, editors. Sexual knowledge, sexual science: the history of attitudes to sexuality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall LA. Hidden anxieties: male sexuality, 1900-1950. Oxford: Polity; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall LA. Heroes or villains? Reconsidering British fin de siecle sexology. In: Segal L, editor. New sexual agendas. London: MacMillan; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kutchins H, Kirk S. Making us crazy: DSM—the psychiatric bible and the creation of mental disorder. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conrad P, Markens S. Constructing the “gay gene” in the news: optimism and scepticism in the US and British press. Health. 2001;5:373–390. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall LA. Venereal diseases and society in Britain, from the Contagious Diseases Act to the National Health Service. In: Davidson R, Hall LA, editors. Sex, sin and suffering: venereal disease and European society since 1870. London: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson R. “The price of the permissive society”: the epidemiology and control of VD and STDs in late-twentieth-century Scotland. In: Davidson R, Hall LA, editors. Sex, sin and suffering: venereal disease and European society since 1870. London: Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chief Medical Officer. Main report of the CMO's expert advisory committee on. Chlamydia trachomatis. London: Department of Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jowell R, Curtice J, Park A, Thomson K, Jarvis L, Bromley C, et al. British social attitudes, the 17th report: focusing on diversity. London: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks L. Sexual chemistry: a history of the contraceptive pill. London: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foucault M. The history of sexuality, volume 1: an introduction. New York: Pantheon; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WB, Martin CE. Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WB, Martin CE, Gebhard PH. Sexual behavior in the human female. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human sexual response. Boston: Little Brown; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson AM, Wadsworth J, Wellings K, Field J. Sexual attitudes and lifestyles. Oxford: Blackwell; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson AM, Mercer CH, Erens B, Copas AJ, McManus S, Wellings K, et al. Sexual behaviour in Britain: partnerships, practices, and HIV risk behaviours. Lancet. 2001;358:1835–1842. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06883-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wellings K, Nanchahal K, MacDowall W, McManus S, Erens B, Mercer CH, et al. Sexual behaviour in Britain: early heterosexual experience. Lancet. 2001;358:1843–1850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06885-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fenton K, Korovessis C, Johnson AM, McCadden A, McManus S, Wellings K, et al. Sexual behaviour in Britain: reported sexually transmitted infections and prevalent Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Lancet. 2001;358:1851–1854. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06886-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Althof S, Seftel A. The evaluation and management of erectile dysfunction. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1995;18:171–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feldman H, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauman E, Paik A, Rosen R. Sexual dysfunction in the US: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcuse H. Eros and civilization. Boston: Beacon Press; 1955. [Google Scholar]