Summary

Little is known about the effect of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2 or SARS2) vaccine breakthrough infections (BTIs) on the magnitude and breadth of the T cell repertoire after exposure to different variants. We studied samples from individuals who experienced symptomatic BTIs during Delta or Omicron waves. In the pre-BTI samples, 30% of the donors exhibited substantial immune memory against non-S (spike) SARS2 antigens, consistent with previous undiagnosed asymptomatic SARS2 infections. Following symptomatic BTI, we observed (1) enhanced S-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell responses in donors without previous asymptomatic infection, (2) expansion of CD4 and CD8 T cell responses to non-S targets (M, N, and nsps) independent of SARS2 variant, and (3) generation of novel epitopes recognizing variant-specific mutations. These variant-specific T cell responses accounted for 9%–15% of the total epitope repertoire. Overall, BTIs boost vaccine-induced immune responses by increasing the magnitude and by broadening the repertoire of T cell antigens and epitopes recognized.

Keywords: breakthrough infection, T cells, B cells, COVID-19 vaccination, SARS-CoV-2, Delta, Omicron, de novo responses, coronavirus

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

30% of donors pre-BTI show non-S-T cells, implying prior asymptomatic infection

-

•

BTIs boost S-specific T cells in donors without prior asymptomatic infection

-

•

CD4 and CD8 T cell responses to non-S targets (M, N, and nsps) increase after BTI

-

•

BTIs induce novel T cell epitopes containing variant-specific mutations

Tarke et al. explore the influence of breakthrough infections (BTIs) on SARS2 adaptive immunity. BTIs enhance T cell responses in terms of magnitude and breadth of antigens recognized, expanding recognition to non-spike antigens. BTIs are also associated with responses to novel epitopes recognizing variant-specific mutations from Delta and Omicron variants.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2 or SARS2) remains a fundamental threat to global health and a leading cause of death. Understanding the prospects for the long-term evolution of infections and associated diseases is a high priority. As the SARS2 pandemic moved into 2023, large segments of the population had received multiple vaccinations, been infected multiple times, or both. In the United States, between January 2020 and October 2023, a total of 103,436,829 confirmed cases of COVID-19 (corresponding to 30.4% of the general population) were reported to the World Health Organization.1 Worldwide, confirmed cases amounted to 771,151,224 (9.6%). Individuals vaccinated but not infected, or only infected but never vaccinated, are becoming uncommon.

SARS2 breakthrough infection (BTI) in COVID-19-vaccinated subjects has become prevalent. Repeated vaccinations, updated boosters, and BTIs contribute to building an “immunity wall” that, while not necessarily effective in preventing reinfection, is still effective at preventing severe disease.2,3 This is in line with the observation that, after the widespread COVID-19 vaccination campaign, a general decrease in rates of hospitalization and death in vaccinated individuals was observed despite the continued appearance of new variants.4,5,6,7,8

T cells have been demonstrated to play a role in modulating disease severity and preventing severe COVID-19.9,10,11,12 We and others have also previously shown that memory T cell responses induced by natural infection or vaccination are still largely effective in recognition of several SARS2 variants, including Omicron.12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 Several studies found that repeated immunizations and BTIs boost antibody responses, while T cell responses were less enhanced by multiple exposures. This pattern is consistent with the more stable kinetic behavior noted for SARS2 memory T cells (versus more rapidly waning antibody responses),15,21,22,23 although levels of memory T cells in the peripheral blood may not account for an increase in memory T cells in airway tissues.24,25,26,27,28 Some studies implicated a detrimental effect of the infection, resulting in decreased measured responses and increased markers of T cell exhaustion.29 In another study, robust activation and expansion of spike (S) -specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells was observed in BTIs in addition to responses to non-S antigens.28 To date, most studies on BTI and T cell responses have had a narrow focus on the effect on bulk memory T cells30,31 or S antigen.22,26,32,33,34,35,36,37 Thus, the effect of BTIs on T cell immunity warrants further investigation. Specifically, the long-term effects of symptomatic BTI have not yet been comprehensively investigated, particularly at the level of boosting S- versus non-S-specific responses, the effects on T cell epitope repertoire, and the potential development of responses to novel mutated epitopes.

A broad and multi-antigenic memory T cell response associated with natural infection can contribute to infection control,12 suggesting that non-S responses are also important. Selected studies focused on some specific immunodominant epitopes27,37,38 and demonstrated that non-S responses are generated post BTI, but studies broadly characterizing the epitope repertoire are lacking. It is thus important to determine to what extent BTIs are associated with broad responses against antigens beyond S, providing a potential qualitative advantage in T cell responses. It is also possible that prior immunizations imprint T cell responses and a pre-existing S response inhibits the development of T cell responses against other SARS2 antigens, possibly reflective of vaccination limiting the infection process and the associated antigen load. Relevant to this issue, we have developed reagents to separately monitor T cell responses to S and the rest of the SARS2 proteome,23 allowing discernment of S responses associated with vaccination from responses associated with infection.

Further, it is important to ascertain whether recognition of new variant-specific epitopes following a particular BTI affects the ability of T and B cells to cross-recognize other variants. Antibody responses induced by vaccination with ancestral S have a decreased capacity to neutralize SARS2 variants.19,35,39,40,41 Neutralizing antibodies against Omicron are detected after a booster (third dose) after the primary mRNA vaccine series with ancestral S.42,43,44 The B cell responses recognizing variants that are detected after variant-containing booster vaccination45 or BTI46,47,48,49,50,51 are predominantly mediated by cross-reactive SARS2-specific B cells, as opposed to de novo variant-specific responses. During this phenomenon of immune imprinting, the first antigenic exposure (here with ancestral S) shapes the immune responses after subsequent variant exposures (i.e., Delta or Omicron). Reactivation of S-binding memory B (BMem) cells that recognize epitopes shared between the vaccinated (ancestral) and the infected strains define the course of humoral immunity.52 Whether similar mechanisms operate at the level of T cell responses is currently unknown. New epitopes created by the variant-associated mutations could represent an important mechanism allowing T cellular immunity to keep pace with SARS2 evolution.

In this study, we analyze a large cohort of donors that experienced BTI during either the Delta or Omicron variant waves with samples collected before and several months after the infection to assess the magnitude and functionality of T cell responses, including epitope mapping to identify potential generation of novel variant-specific epitopes.

Results

Characteristics of SARS2 BTI cohorts

We assessed adaptive immunity in three cohorts encompassing a total of 100 adults previously vaccinated with at least two doses of COVID-19 vaccines who experienced BTI with SARS2, confirmed by PCR or antigen tests. Characteristics of these cohorts are summarized in Table S1. All but three (97%) experienced mild peak disease severity, and the remaining donors reported asymptomatic infections.

The first longitudinal cohort (cohort 1) of 27 donors experienced a BTI in the December 2021 to June 2022 period, when the Omicron sublineage BA.1 was the most prevalent SARS2 variant in San Diego, California.53 A second cross-sectional cohort (cohort 2) included three subsets of 19 or 20 donors each, who experienced BTIs during the Delta, Omicron BA.1, and BA.5 waves, respectively. A third cohort of 15 apheresis donors was utilized for antigen and epitope identification studies (cohort 3) and included donors who reported a BTI during the Delta or Omicron waves.

Participants' median age was 37–43 years across cohorts, with individual ages ranging from 20 to 74 years. The cohorts were 70% female and 30% male, primarily white (71%). Vaccines administered were Pfizer (36%), Moderna (35%), Novavax (3%), or a combination (26%). These demographics reflect the overall composition of the volunteers who enrolled for the La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) COVID-19 studies.

In terms of number of vaccinations, 54% of BTI donors received three doses, 35% two, and 11% four. Plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) samples were collected 27–120 days post BTI to capture changes in adaptive memory. We performed serological assays for cohorts 1 and 2. Unsurprisingly, since all donors were vaccinated, all donors were seropositive for RBD antibodies. However, due to the limited sensitivity of nucleocapsid (N) serological tests, only 67% of the samples were positive for N immunoglobulin (Ig) G following BTI23,54 (Table S1).

BTI boosts CD4+ T cell responses to S and non-S antigens

To assess the impact of symptomatic BTI on cellular adaptive immune responses, we used PBMCs collected before and after the reported BTI from the longitudinal cohort (cohort 1) and assessed T cell responses to ancestral S using a peptide megapool (MP) of overlapping 15-mers and a previously described MP of experimentally defined non-S epitopes (CD4-RE). The CD4-RE MP immunodiagnostic tool can distinguish between SARS2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination history23 and predominantly detects epitopes non-cross-reactive with other coronavirus species. T cell responses were measured by assessing activation and functionality using a combined activation-induced marker and intracellular cytokine staining (activation-induced cell marker [AIM] + intraceullar cytokine secretion [ICS]) assay as previously reported19 (Figure S1A). Here, we confirmed the previously reported difference in sensitivity between the non-S T cell assay and the N-serological assay23 also in the case of documented BTIs. Specifically, the samples collected post BTI showed CD4+ T cell responses to non-S antigens (CD4-RE) in 85% of the cohort (Figure 1), while N-serology-positive responses were found in 63% of the cohort (Table S1).

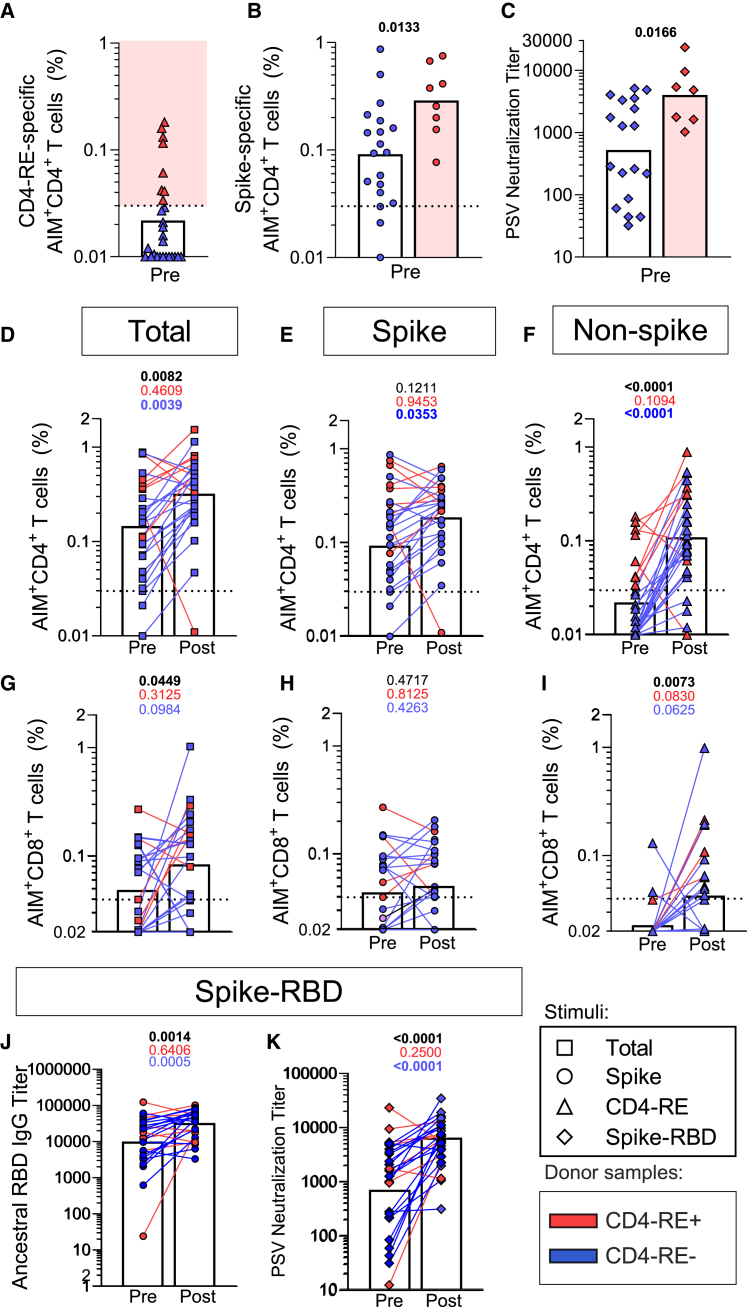

Figure 1.

Impact of BTIs on T cell, RBD, and neutralizing antibody responses

T cell responses and neutralizing responses assessed in a longitudinal cohort (cohort 1, Table S1) of COVID-19-vaccinated individuals (n = 27), sampled before and after BTI (median 89 days). For T cells, ancestral S responses are shown as circles, non-S (CD4-RE) responses as triangles, and the sum of S and non-S reactivity as squares. For antibodies, S-RBD responses are shown as rhombuses.

(A and B) CD4+ T cell reactivity to (A) CD4-RE and (B) S protein for pre-BTI samples, with CD4-RE+ highlighted in red and non-reactive samples in blue.

(C) PSV neutralization titers.

(D–F) Pre- and post-BTI CD4+ T cell responses for (D) total responses and separately for (E) S and (F) non-S proteins.

(G–I) CD8+ T cell responses for (G) total responses and separately for (H) S and (I) non-S proteins.

(J and K) The ancestral (J) S-RBD IgG and (K) PSV neutralization titers in pre- and post-BTI samples. Bars represent geometric mean. Pre-post comparisons are performed by paired Wilcoxon T test and p values are listed at the top of each graph for the entire cohort (black), CD4-RE+ (red), and CD4-RE- (blue) donor samples. The y-axis starts at the LOD, and the dotted line indicates the LOS. See also Figures S1, S2, and Table S1.

Unexpectedly, 30% (8 out of 27) of pre-BTI samples exhibited CD4+ T cell responses to non-S antigens (CD4 reminder of proteome experimentally defined [CD4-RE]) (Figure 1A) and 19% were N-serology positive (Table S1). In our current study, we selected an arbitrary cutoff of 0.03% for AIM+ CD4+ T cells, 2-fold higher than previously used,23 to be conservative, and select only high CD4RE responders, corresponding to undetected BTIs. With this cutoff combining vaccinated and unexposed pre-pandemic cohorts, only 6.7% were positive for CD4-RE. This is substantially lower than the 30% we reported in this study (p = 0.0018 by the Fisher exact test). In this current study, our donors had received vaccines only containing the SARS2 S antigen and had not reported COVID-19-related symptoms or positive tests. The samples with CD4-RE reactivity (CD4-RE+) also had a higher magnitude of S-specific CD4+ T cells (p = 0.0133; Figure 1B) but no increase in CD8+ T cells (p = 0.7390; Figure S2A). While we did not observe a significant difference in the ancestral RBD IgG titers between CD4-RE+ and CD4-RE− subjects (p = 0.0846; Figure S2B), a significant increase in neutralizing antibody titers was observed (p = 0.0552; Figure 1C). The most plausible explanation for these findings is that these donors had experienced an asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. This is suggested by the detection of non-S CD4+ T cell response based on reactivity to CD4-RE, previously designed to capture primarily non-S SARS2 responses minimizing measurement of pre-existing common cold coronavirus responses23 and the significant increase of CD4+ S reactivity and neutralizing antibody titers.

Next, we assessed the overall effect of symptomatic BTI on the longitudinal cohort as whole or by dividing individuals with (red) and without (blue) pre-existing non-S immunity (Figure 1A). Post BTI, an increase in total SARS2-specific CD4+ T cell reactivity was observed (p = 0.0082; Figure 1D in black), driven mostly by non-S responses (p < 0.0001; Figure 1F in black) rather than S responses (p = 0.1211; Figure 1E in black). Notably, in samples with probable asymptomatic SARS2 infection based on the CD4-RE reactivity, no appreciable boost was observed in S or non-S CD4+ T cell responses after the recorded BTI (S p = 0.9453; non-S p = 0.1094; Figures 1E and 1F in red). Conversely, the samples without CD4-RE reactivity had a significant increase in both S and non-S CD4+ T cell responses after BTI (magnitude: S p = 0.0353; non-S p < 0.0001; Figures 1E and 1F in blue). Thus, a single BTI provides an effective boost to the overall CD4+ T cell response to SARS2 S and non-S epitopes. In contrast, subsequent BTIs marginally affected the overall magnitude of CD4+ T cell responses.

Increased CD8+ T cell responses to non-S antigens after BTI

Similar to what was observed in the case of CD4+ T cell responses, an overall increase in the total post-BTI CD8+ T cell response was noted (p = 0.0449; Figure 1G in black). The CD8+ T response to S remained unaltered post BTI (p = 0.4717; Figure 1H in black), while the overall increase was also in this case driven by non-S CD8+ T cell reactivity (p = 0.0073; Figure 1I in black). However, when we divided the cohort based on the presence or lack of CD4-RE response prior to the documented BTI, no significant relationship was observed when combining S + non-S CD8+ T cell responses (CD4-RE+, p = 0.3125 in red, CD4-RE−, p = 0.0984 in blue; Figure 1G) or when considering non-S CD8+ T cell responses only (CD4-RE+, p = 0.0830 in red, CD4-RE−, p = 0.0625 in blue; Figure 1I).

Taken together, the data show that both the CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses are not reduced following BTI. Both S- and non-S-specific CD4+ T cell responses improved in magnitude following BTI in the absence of detectable CD4-RE reactive CD4 T cells before the documented BTI. For CD8+ T cells, only non-S-specific responses were boosted by BTI and no relationship was observed with CD4-RE reactive CD4 T cells before the documented BTI. The lack of booster effect in S and increase boosting effect in the non-S-specific responses was observed also when median fluorescence intensity (MFI) was analyzed (data not shown).

RBD-binding and neutralizing antibodies after a single BTI

Finally, we investigated the impact of BTIs on antibody responses. An increase in RBD IgG titers was observed post BTI (p = 0.0014; Figure 1J in black). Likewise, we observed an increase in the neutralizing antibody titers (p = 0.0006 Figure 1K in black). Similar to CD4 T cell responses, the increases in RBD IgG and neutralizing antibody titers were predominantly observed in CD4-RE− donors (p = 0.0005, Figure 1J and p < 0.0001, Figure 1K, in blue). Overall, a single BTI boosted the antibody response to ancestral SARS2 RBD, while subsequent BTIs had a more marginal impact.

S-specific T cell memory subsets, cTFH, and exhaustion markers are mostly unaffected after BTI

In addition to determining the effect on the magnitude of T cell responses post BTI, we investigated the effects on the quality of the T cell responses. We assessed the memory phenotypes of S-specific T cells, the fraction of circulating T follicular helper cells (cTFH), and the expression of markers associated with exhaustion.55 Figure S1A shows gating strategy and representative fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) plots for both analyses. As expected, the majority of S-specific CD4+ T cells were T central memory (CD45RA−CCR7+) and T effector memory (CD45RA−CCR7-) (Figure 2A). The distribution of memory populations within the S-specific CD4+ T cells did not change between the pre-and post-BTI longitudinal samples (Figure 2A). Similarly, there was no difference in the proportion of S-specific cTFH cells in pre- and post-BTI samples, regardless of pre-existing non-S reactivity (Figures 2B and S2C).

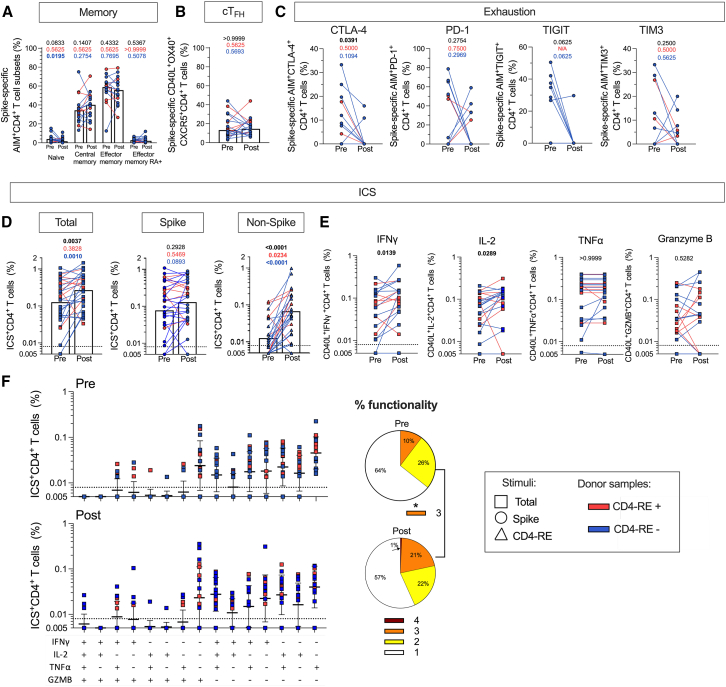

Figure 2.

CD4+ T cell antigen-specific immunophenotyping

CD4+ T cell responses evaluated in the longitudinal cohort (cohort 1, Table S1) of COVID-19-vaccinated individuals (n = 27) sampled before and after BTI (median 89 days). The T cell responses are shown for ancestral S (circles), non-S (CD4-RE) (triangles), and the sum of S and non-S reactivity (squares).

(A–C) Immunophenotyping of AIM-positive S-specific CD4+ T cell responses considering (A) memory subsets (CD45RA and CCR7), (B) cTFH fraction (CXCR5 expression on OX40+CD40L+ cells), and (C) exhaustion (CTLA-4, PD-1, TIGIT, and TIM3).

(D and E) Antigen-specific cytokine and granzyme B responses in CD40L+ cells. (D) total, S, and non-S-specific responses and (E) sum of S and non-S IFNγ, IL-2, TNFα, and granzyme B responses.

(F) Pie chart of single or combined cytokine/granzyme B production (function count: red = 4, orange = 3, yellow = 2, white = 1). Pre-post comparisons are performed by paired Wilcoxon T test; p values are listed at the top of each graph for the entire cohort (black), CD4-RE+ (red), and CD4-RE- (blue) donor samples. Bars represent the geometric mean, except for the memory and cTFH graphs which show the median to account for zero values. The y-axis begins at the LOD, and the dotted line represents the LOS. See also Figures S1, S2, and Table S1.

Following early concerns that breakthrough COVID-19 infections could be the result of exhausted immune cells after multiple COVID-19 vaccinations,29,56,57 we assessed exhaustion marker expression (cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 [CTLA-4], programmed cell death protein 1 [PD-1], TIGIT, and TIM3) on S-specific T cells for cohort 1 based on donors associated with a sufficiently vigorous AIM+ response to allow co-measure of exhaustion markers in AIM+ CD4 and CD8 T cells. We found either no change post BTI or significant lower exhaustion markers on CD4+ T cells (Figure 2C, CTLA-4 Wilcoxon test p = 0.0391 in black).

We evaluated the quality of S-specific CD8+ T cell responses and observed no changes in memory subsets (Figure S2D) or the expression of exhaustion markers CTLA-4, PD1, TIGIT, and TIM3 pre and post BTI (Figure S2E). We further analyzed combinations of these markers to detect variations in polyexhaustion among spike-specific T cells post BTI (Figures S2F and S2G). Our findings indicate that BTIs did not lead to increased exhaustion in S-specific CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Instead, there appeared to be a general trend toward reduced expression of exhaustion markers.

Increase in cytokine-producing non-S T cells and polyfunctionality after BTI

Production of interferon gamma (IFNγ), interleukin (IL)-2, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), and granzyme B in combination with CD40L was measured in response to S or non-S MPs (see Figure S1A for gating strategy). The overall sum of all cytokines and granzyme B for CD4+ T cell responses demonstrated an increase in the total (S + non-S) responses (p = 0.0037; Figure 2D in black). The increase was primarily in subjects lacking baseline non-S CD4+ T cell reactivity (p < 0.001; Figure 2D in blue). Cytokine-producing cell increases were observed for IFNγ (p = 0.0139) and IL-2 (p = 0.0289) (Figure 2E), and polyfunctional (3+ cytokines) CD4 T cells (p = 0.0275; Figure 2F). Regarding CD8+ T cell responses, no difference was seen for total (S + non-S) ICS+CD8+ T cells (Figure S2H), while a significant increase in non-S-specific ICS+CD8+ T cells was observed post BTI (p = 0.0088; Figure S2H). However, no significant differences were observed when analyzing the cytokines individually in relation to the sum of S and non-S-specific CD8+ response (Figure S2I). These results indicate that the functionality of the CD4+ T cell response increases following BTI and is mainly due to an increase in IFNγ+TNFα+IL-2+ polyfunctional memory T cells. Conversely, regarding CD8+ T cells, the data suggest BTIs can generate novel non-S CD8+ T cell responses but BTIs are less efficacious in boosting circulating S-specific CD8+ T cells.

Delta or Omicron variant waves of BTIs do not differentially affect T cell responses

To examine whether BTIs in different variant waves were associated with T cell recognition of that variant, ancestral, or other variant S proteins, we tested T cell responses to ancestral, Delta, Omicron BA.1, and Omicron BA.5 S MPs in BTI donors during the Delta and Omicron waves in a cohort collected post BTI (cohort 2, Table S1). First, we explored whether vaccine-elicited S memory T cells would alter the relative balance of S vs. non-S T cell responses post BTI. Previously,23 we demonstrated that the S and CD4-RE CD4+ T cell reactivity can discriminate subjects who experienced natural infection (typically with non-S > S) from those with hybrid immunity donors (infected and then vaccinated non-S < S). In a similar two-dimensional space, we now assessed CD4+ T cell responses to the ancestral S and CD4-RE MPs as a function of exposure to different SARS2 variants in the context of BTI. No obvious pattern was discernible related to the variant wave (χ2 test p = 0.3458; Figure 3A), vaccine doses, or the time point post BTI (Figure S3A). Overall, these data provide additional evidence that vaccine-induced S-specific CD4+ T cells did not block the development of non-S CD4+ T cell responses to a BTI.

Figure 3.

T and B cell responses in BTI donors as a function of Delta or Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant wave

T and B cell responses assessed in a cross-sectional cohort (cohort 2, Table S1) of BTI donors infected during Delta (n = 24 at 3 months post symptoms onset [PSO]), Omicron BA.1 (n = 20 at 1 month PSO, n = 32 at 3 months PSO), or Omicron BA.5 (n = 19) SARS2 variant waves.

(A) AIM+CD4+ T cell responses to S and CD4-RE are displayed on a two-dimensional plot, categorized by response type (none, S only, non-S only, non-S > S, non-S < S) with color-coded variant groups (Delta, orange; Omicron BA.1, dark blue; Omicron BA.5, purple). p values are shown for the χ2 to assess response distribution across categories T cell reactivity. The percentage of each donor sample cohort in the different categories is shown as a bar graph.

(B and C) AIM+CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response to ancestral S comparing (B) Delta versus Omicron BA.1 or (C) BA.1 versus BA.5 BTI. Bars represent the geometric mean and p values are shown for Mann-Whitney tests.

(D and E) (D) Frequency of ancestral (Anc) RBD-binding BMem (among total B cells) for Delta or BA.1 donors and (E) composition of BMem subsets among ancestral, Delta or BA.1 RBD-binding BMem in Delta or Omicron BA.1 BTI donors.

(F and G) (F) Ancestral RBD IgG binding endpoint titers and (G) neutralization of SARS2 ancestral S PSV in Delta or Omicron donors. p values are shown for paired Wilcoxon t tests for the magnitude graphs. The y-axis begins at the LOD, and the LOS is indicated by the dotted line. See also Figures S1, S3, and Table S1.

We then directly compared the total ancestral SARS2-specific T cell responses after BTI as a function of the different variant waves of infection. The total T cell response combining the magnitude of S and CD4-RE or T cell responses showed no significant difference in CD4+ and CD8+ AIM+ T cell responses between donors affected by Delta or Omicron BA.1 (CD4, p = 0.9310; CD8, p = 0.9758; Figure 3B). Similar outcomes were observed when comparing responses post Omicron BA.1 and BA.5 infections (CD4, p = 0.7024; CD8, p = 0.3877; Figure 3C). The total ICS+ SARS2-specific T cell response was also comparable between both Delta and Omicron BA.1 and the Omicron sub-lineages, BA.1 and BA.5 (Delta vs. BA1, CD4 p = 0.8175 CD8, p = 0.9944; BA.1 vs. BA.5 CD4 p = 0.4780, CD8 p = 0.5865; Figures S3B and S3C). Overall, BTI with either Delta or Omicron variants did not differentially affect the magnitude of CD4+ or CD8+ T cell responses to ancestral S and non-S antigens.

Impact on antibody and B cell responses of Delta or Omicron variant wave BTIs

We next investigated in the cross-sectional cohort collected post BTI (cohort 2, Table S1) the antibody and B cell responses as a function of the SARS2 variant associated with the COVID-19 wave when the BTI occurred, to compare memory B cell and T cell specificities. The overall frequency of ancestral RBD-binding BMem cells was similar after Delta or Omicron BA.1 BTIs (p = 0.9391; Figure 3D). Likewise, similar frequencies were observed of Delta or Omicron BA.1 RBD-binding BMem cells (p = 0.9612 and p = 0.1726; Figure S3D). In addition, a classical CD27+CD21+ phenotype was the predominant phenotype among ancestral RBD-binding BMem for both Delta and Omicron BA.1 BTI cases (Figure 3E). In all cases, the RBD-binding BMem cells were predominantly IgG1+ (Figure S3F).

For RBD serum IgG, there were no significant differences in the endpoint titers of ancestral RBD-binding IgG between Delta and BA.1 BTI donors (p = 0.9254; Figure 3F). Ancestral virus neutralizing antibody titers were also not different between Delta and BA.1 BTI donors (p = 0.5648; Figure 3G).

BTI is associated with a boost to T cell responses to multiple non-S antigens

Previous studies addressed the breadth and poly-antigenic nature of the T cell response after natural infection or vaccination.12,58,59,60,61,62 However, little is known about the effects of sequential COVID-19 vaccination followed by BTI on the breadth of T cell responses and the generation of non-S responses.

To determine which SARS2 antigens besides S were recognized after BTI, and to detail the molecular mechanisms of variant cross-recognition, we enrolled an additional cohort (n = 15) hereafter called the antigen/epitope ID cohort (cohort 3; Table S1). Within this cohort, five donors had a BTI during the Delta variant wave (July to early December 2021) and 10 had a BTI during the Omicron variant wave (late December 2021 to July 2022), thus classified in the sub-lineages BA1 (December 2021 to June 2022) and BA5 (June to July 2022) (https://cov.lanl.gov/). We compared T cell responses from this cohort with those observed in the pre-BTI samples from the longitudinal cohort (cohort 1) described in Table S1. Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing for the epitope ID cohort is shown in Table S2.

Consistent with prior longitudinal findings (Figure 1), the antigen/epitope ID cohort exhibited increased non-S CD4+ T cell responses compared to vaccinated-only samples (Mann-Whitney test p = 0.0075; Figure 4A). Specificity analysis of CD4+ T cell responses using individual peptide pools of overlapping 15-mers specific for each antigen (see STAR Methods) revealed significant responses to multiple non-S antigens following BTIs, including membrane (M) and N (one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank t test, M p = 0.008; N p = 0.0005; Figure 4B). This demonstrates that the repeated COVID-19 S-based vaccinations prior to BTI did not prevent the generation of CD4+ T cell responses to multiple non-S antigens post infection.

Figure 4.

SARS-CoV-2 antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in vaccinated-only or post-BTI donor samples

AIM+ T cell responses in COVID-19 vaccinated only (n = 20, light blue; pre-samples of cohort 1 Table S1) and BTI (n = 15, black) individuals (cohort 3 Table S1). Both cohorts were tested for S and non-S (CD4-RE); the BTI cohort was additionally tested for all the protein antigens.

(A and B) (A) CD4+ T cell responses to total (S + non-S CD4-RE) S and non-S (CD4-RE) and (B) individual antigens.

(C and D) (C) CD8+ T cell responses to total (S + non-S CD4-RE) S and non-S (CD4-RE) and (D) individual antigens. Statistical comparisons across cohorts are done by the Mann-Whitney test. p values above the individual antigens are calculated by using one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank test compared to the limit of sensitivity (LOS). The y axes start at the limit of detection (LOD), and the dotted lines represent the LOS. See also Figure S1, and Table S1.

Analysis of the CD8+ T cell response in the antigen/epitope ID cohort compared to vaccinated-only individuals revealed increased total, S, and non-S responses in the breakthrough samples (Mann-Whitney test, total p = 0.0011, S p = 0.009, and non-S p = 0.014; Figure 4C). Non-S CD8+ T cell responses were against multiple antigens, with N being the most recognized (one-sample Wilcoxon signed-rank t test, S p = 0.0002; N p = 0.031; Figure 4D). These data show that BTI is associated with broad CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses. Multiple different non-S antigens are recognized, in addition to T cell responses to S being maintained or boosted.

T cell responses after BTI target conserved epitopes as well as novel variant epitopes

Using a previously reported strategy,19,58 we identify the specific T cell epitopes recognized in donors who experienced a Delta (n = 5) or Omicron BA.1 (n = 5) BTI (cohort 3 Table S1 and Figure 4). To identify CD4+ T cell epitopes, we tested overlapping 15-mer peptides from the original antigen-specific pools. For CD8+ T cell epitopes, we synthesized the top 2% of predicted 9- and 10-mers corresponding to the HLA of each donor and the specific antigens recognized in that donor. All positive antigens were deconvoluted to the level of individual peptides.

We and others have previously shown that the majority of the T cell responses to Delta and Omicron SARS2 variants were preserved, and the sequences of the majority of T cell epitopes were not affected by variant mutations.13,14,15,16,19 We expanded on these results in our current study by quantifying the impact of variant mutations on the T cell epitopes identified by testing per each epitope-donor combination, the equivalent mutated peptide pertaining to the Delta or Omicron variant. Additionally, we also tested any 15-mer or predicted 9-mer/10-mer containing Delta or Omicron amino acid mutations to test the hypothesis that novel epitopes can be generated following variant-specific infection. The full list of epitopes identified in this study is available in Table S3. Each peptide was showed to elicit a T cell response in AIM assays utilizing individual peptides.

In the case of CD4+ T cells, we identified a total of 158 unique epitopes and 207 epitope-donor combinations, because some epitopes were recognized in multiple donors (Table S3). The majority of the CD4+ T cell epitope-donor combinations identified were completely conserved between ancestral strain and the variants (Delta 46 out of 51 = 90%, Figure 5A; and Omicron 105 out of 149 = 70%, Figure 5C). In Delta BTI donors, of the five epitope-donor combinations mutated in the Delta strain, two were associated with a loss of the CD4+ T cell response and the other three were associated with generation of a novel response (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Impact of variant sequences on CD4+ and CD8+ T cell epitopes in Delta and Omicron BTI donors

SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell epitopes in Delta (n = 5; orange) and Omicron BA.1 (n = 5; dark blue) BTI individuals (cohort 3 Table S1).

(A–D) CD4+ T cell epitopes include conserved (A and C) and mutation-affected (B and D). Mutation impacts are categorized by response changes: increased, unchanged, decreased, or novel.

(E–H) CD8+ T cell epitopes include conserved (E and G) and mutation affected (F and H) and categorized responses. The number of epitopes is indicated at the top of each graph. The dotted line represents the LOS, and the y-axis begins at the LOD. See also Figure S1 and Tables S1, S2, and S3.

The Omicron BA.1 variant contains more mutations than Delta63 and more CD4+ T cell epitopes-donor combinations were associated with mutations in the variant sequence (n = 44) (Table S3 and Figure 5D). Of these epitope-donor combinations, 23 resulted in a decrease or total loss of CD4+ T cell recognition in Omicron BTI subjects (Figure 5D). Of the remaining 21, two were associated with an increase in CD4+ T cell recognition and three with no change in CD4+ T cell recognition. Notably, novel CD4+ T cell responses to the variant sequences were associated with the remaining16 mutated Omicron epitope-donor combinations (Figure 5D). Overall, the data demonstrate at the single-epitope resolution a general preservation of the CD4+ T cell response to both Delta and Omicron SARS2 variants, in which loss of some ancestral epitopes was counterbalanced by the gain of responses to novel variant epitopes.

For CD8+ T cells, we identified a total of 87 epitopes and epitope-donor combinations, with each epitope recognized in a single donor (Table S3). Epitope conservation was more frequent than what was observed for the CD4 counterpart (Delta 22 out of 23 epitopes = 96%, Figure 5E, and Omicron 54 out of 58 epitopes = 93%, Figure 5G). For Delta BTI subjects, we found a novel response to one mutated epitope and no epitopes associated with decreases (Figure 5F). For Omicron BTI subjects, four epitopes were affected by an Omicron BA.1 mutation, three epitopes were associated with a decrease, and one was associated with a novel CD8+ T cell response (Figure 5H, right panels). Thus, the CD8+ T cell epitope repertoire was largely conserved in response to Delta and Omicron SARS2 variants, with some novel epitope-specific responses generating BTI, similar to the CD4+ T cell responses to matched variants.

Overall impact of Delta mutations in total T cell response after Delta and Omicron BTI

The results in the previous section were based on epitope identification in a small cohort of samples (cohort 3, Table S1). We expanded by considering all BTI cohorts (Table S1), using S and non-S (CD4-RE) MPs and including peptide pools focused on the mutated portions of the SARS2 virus only and testing ancestral and variant version of it. Accordingly, we designed two pools including 50 peptides each for Delta and two pools including 116 peptides for BA.1. In both cases, the peptides for the ancestral or variant peptide version were pooled separately. First, we estimated the fraction of the total T cell response targeting regions affected by mutations. The total response was calculated as the sum of S and CD4-RE MPs and the response to mutated regions was based on reactivity to the pool encompassing all ancestral peptides mutated in Delta or Omicron. The fraction of response mutated was calculated based on the geomean values. In Delta BTIs, only 6% and 14% of the total CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response, respectively, was targeted regions associated with mutations (CD4+ geometric mean, total 0.315%; affected in Delta 0.020%, p < 0.0001; CD8+ geometric mean, total 0.138%, affected in Delta 0.020%, p = 0.0002; Figure 6A). No significant differences were observed when comparing the ancestral and Delta versions of mutation-associated pools (CD4, p = 0.3828; CD8, p = 0.4688; Figure 6A). Thus, regions associated with mutated sequences account for a minority of the responses, both in quantity and magnitude.

Figure 6.

Impact of variant sequences on the total T and B cell responses in Delta and Omicron BTI donors

SARS2-specifc T cell responses in the BTI cohorts collected post infection from this study (Table S1; Delta n = 24; Omicron BA.1 n = 68) measuring S and CD4-RE MPs. Responses to variant-specific mutations are analyzed using ancestral and variant peptide pools.

(A and C) SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells in total (S + non-S) responses (light gray) compared to peptides affected by Delta (A) or Omicron BA.1 (C) mutations, using ancestral (A in dark gray; C in brown) and variant-specific peptides (Delta in orange, A; Omicron in blue, C).

(B and D) The bar graph displays the percentage of preserved response per donor, calculated by subtracting the response to the ancestral pool affected by Delta (B) or Omicron BA.1 (D) mutations from the total (S + CD4-RE). The pie chart illustrates the percentage of individuals showing no change (± 0.005%), increase, novel, or decreased responses when comparing the ancestral and variant-specific peptide pools.

(E) Ancestral and variant RBD-binding BMem cells are plotted for their cross-reactive and non-cross-reactive binding in switched B cells (IgD−IgM−) for Delta (n = 19) and Omicron BA.1 (n = 20) BTI donors of cohort 2 (Table S1). p values result from the paired Wilcoxon test and the comparison between ancestral and variant sequences is performed only if at least one value is above the LOS. Bars represent the geometric mean. Graphs start the LOD and the dotted line represents the LOS. See also Figure S1 and Table S1.

We next estimated the percentage of preserved responses per donor by calculating the % [total response (S + CD4-RE) − response measured in the ancestral pool affected by mutations/total response (S + CD4-RE)]. For Delta BTIs donors, an average of 94% and 93% of the CD4 and CD8 T cell responses were preserved (Figure 6B). We then classified each donor as a function of their pattern of responses to the pools of peptides representing regions affected by mutations, in either the ancestral or variant versions. Overall, 65% of the individuals had the same CD4+ T cell response to the ancestral and variant sequences, 9% had a novel response (no response to the ancestral pool but significant response to the variant pool), and 26% had a decrease in response comparing ancestral and variant pools. In the context of CD8+ T cell responses, 54% of individuals had no change, 13% had a novel response, and 33% had a decrease in response to the variant sequences (Figure 6B).

After Omicron BTI, we estimate that 20% and 16% of the total CD4+ and CD8+ T cell response, respectively, was directed to regions associated with mutations in Omicron (CD4+ geometric mean, total 0.357, mutated in Omicron 0.071, p < 0.0001; CD8+ geometric mean, total 0.176, mutated in Omicron 0.029, p < 0.0001; Figure 6C). When calculated on a per-donor basis, on average 76% and 82% of the CD4 and CD8 T cell responses were preserved. Regarding the effect of mutations, 32% of the individuals had the same CD4 T cell response to the ancestral and variant sequences pools, 11% had an increase in responses to the variant pool, 10% had a novel response, and 47% had decreased response to the variant pool. In the context of CD8+ T cell response, 16% was directed to regions associated with mutations in the Omicron variant. On a per-donor basis, 48% of individuals had no change in CD8 T cell response, 15% had an increase, 15% had a novel response, and 22% had some decrease in response (Figure 6D). Although slightly, the number of donors exhibiting no change, increased or novel responses to Omicron mutations following Omicron BTI outnumbers the number of donors negatively affected by the mutations.

Cross-reactive B cell responses are predominantly induced by post-variant BTI

Given the substantial novel T cell responses to a variant BTI (Figures 5 and 6A–6D), we examined the parallel biology of novel B cell responses to variant BTIs. In the same cohort 2 individuals (n = 19 for Delta BTI and n = 20 for Omicron BA.1 BTI) for whom T cell epitopes were defined, we measured BMem capable of binding ancestral, Delta, and/or Omicron BA.1 RBD. The majority of BMem post BTI bound ancestral RBD, with or without cross-reactive binding to variant RBDs (Figures 6E and S1C), indicating they were primed by the ancestral RBD in the COVID-19 vaccines. A rare minority of BMem bound only to Delta RBD (Delta BTI donor mean 4.1% ± 3% SD; Omicron BA.1 BTI donor mean 3.4% ± 2.9% SD) or Omicron BA.1 RBD (Omicron BTI donor mean 2.1% ± 2.3% SD; Delta BTI donor mean 1.7% ± 1.2% SD) and not ancestral RBD (Figure 6E). Both variant BTIs induce predominantly cross-reactive B cell responses. In conclusion, BMem responses after a variant BTI showed considerable imprinting by the ancestral sequence in the vaccines, consistent with other reports.45,46,47,48,49,50,51

Discussion

Our data address the effects of SARS2 BTI on memory T and B cells. Previous studies have shown that BTI infections may occur without any symptoms, thus complicating the data interpretation when analyzing immune responses following infection. We previously showed a limited sensitivity of N serological determination to detect infection and developed a complementary T cell assay able to increase this sensitivity.23 Our study includes this careful control for individuals that had cryptic prior BTIs by analyzing non-S-specific T cell responses, thus allowing us to address this point and help interpretation of previous studies using only serological evidence of previous infection or analyzing only samples collected following BTI. By separately monitoring T cell responses to S and the rest of the SARS2 proteome, we discovered that a large fraction of pre-BTI subjects likely had previous undetected COVID-19 infections. This was consequential for making conclusions regarding T cell memory recall because, while individuals with no history of previous infection showed sizable boosting of T cell responses, much more limited boosting was observed in individuals already possessing T cell memory to non-S antigens. Therefore, we conclude that BTIs can boost S-specific T cells, thus providing direct evidence that this mechanism contributes to the building of an immunity wall against COVID-19.

Increases in S-specific T cell responses have also been previously noted by others following mild or moderate BTI.33,64,65,66,67,68 However, this increase was not observed in more severe and critical cases of infection where instead a delayed S-specific T cell response was observed.69 Here, the largest increases in SARS2-specific T cell responses were observed in individuals with no pre-existing memory of non-S antigens. Overall, these observations highlight the importance of controlling for possible asymptomatic infections by assessing non-S responses.

It has been suggested that SARS2 infection may result in an exhausted immune state in CD8+ T cells in COVID-19 patients. However, in the context of BTIs, our findings did not reveal any evidence of increased exhaustion marker expression. In fact, we observed a trend toward lower expression of certain markers, including CTLA-4.70,71 This observation appears to conflict with one report, wherein convalescent individuals after vaccination demonstrated a substantial reduction in the circulating S-specific CD8+ T cell response accompanied by compromised functionality with impaired cytokine production and lower expression of activation markers, which could suggest an exhaustion state.29 Conversely, an examination of mRNA vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells in individuals with a history of SARS2 infection did not reveal any adverse impact on the functionality of SARS2-specific T cells,28 challenging the hypothesis of an exhausted immune state following SARS2 infection, consistent with our memory T cell findings herein.

We also find that BTIs broaden the T cell response by targeting additional non-S antigens. BTIs have been shown to increase T cell responses by mounting novel non-S-specific responses. Previous studies have shown increased N-specific CD8+ T cells after Omicron BTI32 and increased expansion of non-S CD8+ TCR clones post BTI.37 The observed non-S T cell responses were quick to emerge within the first 2 weeks after the recorded BTI.28 In this study, we also observed a striking increase in the CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses to non-S peptides following BTI. We show that the most dominant antigens following BTIs are also the same antigens previously reported to be most dominant following natural infection in the absence of vaccination samples, and specifically we found responses against N and M across multiple donors.58,72,73,74,75 Together, these data demonstrate the generation of non-S T cell responses following BTI. Since a poly-antigenic response has been associated with less severe disease outcomes,74 it is reasonable to assume that this might provide an advantage and a meaningful contribution to overall SARS2-specific T cell immunity.

Previous studies including our own have addressed the ability of T cells to still be able to recognize mutated epitopes of a specific SARS-CoV-2 variant, particularly in the context of Omicron and Omicron sub-lineages.13,14,19,76,77,78,79,80 We have additionally speculated that infection with SARS-CoV-2 variants should be able to also generate de novo responses,81 although experimental data were lacking in support of this hypothesis. Our data show that infection with one variant does not compromise the capacity of T cell responses to broadly recognize other variants. At the epitope and donor level, we show in detail that most T cell responses are preserved, with some instances of responses against the ancestral sequences being affected by variant-associated mutations. Interestingly, the data revealed that BTIs can generate de novo T cell responses to variant-specific epitopes as previously hypothesized. The number of novel epitopes generated was proportional with the number of mutations in each variant, with Delta being lower than Omicron BA.1. Thus, while some mutations are associated with a decrease in T cell recognition, others are associated with novel responses that compensate for reduced responses associated with variant mutations and allow the T cell response to keep pace with variant evolution. In our study, we were not powered to define specific epitope-HLA combinations with consistent signals of gain or loss and this important question should be addressed in future studies.

The vast majority of BMem after Delta or Omicron BTI recognized ancestral epitopes, indicative of strong imprinting, consistent with published reports.45,46,47,48,49,50 Germinal center responses are required after vaccination or infection to generate diversified affinity matured BMem cells.82 During BTI in the upper respiratory tract, it appears that existing BMem are recalled into germinal centers (GCs) to combat the encountered infecting variant, driving the observed cross-reactivity from ancestral S to the variant.52,83 It is an active area of research to investigate whether repeated exposures to SARS2 variants or large antigenic distances in S induce greater de novo B cell responses.84,85,86The biology of memory T cells and BMem is different, and, in the study here, it appears that human memory T cell responses exhibit less imprinting of the BMem, in that new responses to variant S epitopes represent 9%–15% of T cell responses and only 1.7%–4.1% of BMem responses.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that BTIs effectively enhance the overall T cell response through three mechanisms: (1) increasing the response magnitude to S, (2) de novo recognition of non-S antigens to which the T cells were exposed during the BTI, and (3) de novo S responses to variant-specific epitopes. These data overall underline how BTIs supplement the value of vaccination to build a protective wall based on adaptive responses.

Limitations of the study

Our study is limited to largely mild BTI during the Delta and Omicron BA.1/BA.5 waves. Our current study classified some BTI donors as likely associated with previous asymptomatic infection based on T cell responses to the non-S peptide pool, but the timing and nature of these previous asymptomatic infections were not determined. Variant-specific and cross-reactive BMem cells were gated on Ig-switched B cells to decrease background; however, we could not rule out non-specific binders due to single color identification. Overall, the rate of de novo variant-specific non-cross-reactive BMem cells is likely lower than reported here. Symptomatic BTIs were rare compared to the larger vaccination cohort we enrolled; thus, to analyze samples collected before and after BTI, we could not effectively control confounding factors such as gender and ethnicity. Likewise, our study is not sufficiently powered to determine the effect of the number and timing of previous vaccination exposure on immune responses following BTI. Future studies should investigate further the effects of severe BTI and BTI during additional variant waves, including the recent Omicron BA.2.86 sublineage.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse anti-human CCR7 PE-Fire640 clone G043H7 | BioLegend | Cat# 353262; RRID:AB_2876669 |

| Mouse anti-human CD137 BV421 clone 484-1 | BioLegend | Cat# 309820; RRID:AB_2563830 |

| Mouse anti-human CD137 APC clone 4B4-1 | BioLegend | Cat# 309810; RRID:AB_830672 |

| Mouse anti-human CD14 APC-ef780 clone 61D3 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 47-0149-41; RRID:AB_1834359 |

| Mouse anti-human CD14 V500 clone M5E2 | BioLegend | Cat# 561391; RRID:AB_10611856 |

| Mouse anti-human CD19 APC-ef780 clone HIB19 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 47-0199-42; RRID:AB_1582230 |

| Mouse anti-human CD19 V500 clone HIB19 | BioLegend | Cat# 561121; RRID:AB_10562391 |

| Mouse anti-human CD3 BUV805 clone UCHT1 | BioLegend | Cat# 612895; RRID:AB_2870183 |

| Mouse anti-human CD4 BUV395 clone RPA-T4 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 564724; RRID:AB_2744420 |

| Mouse anti-human CD4 BV605 clone RPA-T4 | BioLegend | Cat# 562658; RRID:AB_2646613 |

| Mouse anti-human CD40L APC clone 2431 | BioLegend | Cat# 310810; RRID:AB_314833 |

| Mouse anti-human CD45RA eFluor450 clone H100 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 48045842; RRID:AB_1272059 |

| Mouse anti-human CD69 BV605 clone FN50 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 562989; RRID:AB_2737935 |

| Mouse anti-human CD69 PE clone FN50 | BioLegend | Cat# 555531; RRID:AB_395916 |

| Mouse anti-human CD8 BUV496 clone RPA-T8 | BioLegend | Cat# 612942; RRID:AB_2870223 |

| Mouse anti-human CTLA4 BV786 clone BNI3 | BioLegend | Cat# 369624; RRID:AB_2810582 |

| Mouse anti-human CXCR5 BV650 clone RF882 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 740528; RRID:AB_2740238 |

| Mouse anti-human Granzyme B AF700 clone GB11 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 560213; RRID:AB_1645453 |

| Mouse anti-human IFNγ FITC clone 4S.B3 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 11-7319-82; RRID:AB_465415 |

| Mouse anti-human IL-2 BB700 clone MQ1-17H12 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 566405; RRID:AB_2744488 |

| Mouse anti-human OX40 PE-Cy7 clone Ber-ACT35 | BioLegend | Cat# 350012; RRID:AB_10901161 |

| Mouse anti-human PD-1 BV711 clone EH12.2H7 | BioLegend | Cat# 329928; RRID:AB_2562911 |

| Mouse anti-human TIGIT (VSTM3) PE-Dazzle594 clone A15153G | BioLegend | Cat# 372716; RRID:AB_2632931 |

| Mouse anti-human TIM3 BV480 clone 7d3 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 746771; RRID:AB_2744030 |

| Mouse anti-human TNFα PE clone Mab11 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 12-7349-82; RRID:AB_466208 |

| Mouse anti-human IgG BUV395 clone G18-145 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 564229; RRID:AB_2738683 |

| Mouse anti-human CD19 BUV563 clone SJ25C1 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 612916; RRID:AB_2870201 |

| Mouse anti-human CXCR3 BUV805 clone 1C6 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 742048; RRID:AB_2871338 |

| Mouse anti-human IgD Pacific Blue clone IA6-2 | BioLegend | Cat# 348224; RRID:AB_2561597 |

| Mouse anti-human CD20 BV510 clone 2H7 | BioLegend | Cat# 302340; RRID:AB_2561941 |

| Mouse anti-human IgM BV570 clone MHM-88 | BioLegend | Cat# 314517; RRID:AB_10913816 |

| Mouse anti-human IgG1 BV650 clone HP6001 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 753703 |

| Mouse anti-human CD27 BB515 clone M-T271 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 564642; RRID:AB_2744354 |

| Mouse anti-human IgA FITC-VioBright clone IS11-8E10 | Miltenyi Biotec | Cat# 130-113-480; RRID:AB_2734076 |

| Mouse anti-human CD79B PerCP-Cy5.5 clone CB3-1 | BioLegend | Cat# 986106; RRID:AB_2936524 |

| Mouse anti-human CD71 PE-Dazzle594 clone CY1G4 | BioLegend | Cat# 334120; RRID:AB_2734335 |

| Mouse anti-human CD11c PE-Cy5 clone 3.9 | BioLegend | Cat# 301610; RRID:AB_493578 |

| Mouse anti-human CD21 AF700 clone Bu32 | BioLegend | Cat# 354918; RRID:AB_2750239 |

| Mouse anti-human CD38 AF810 clone HIT2 | BioLegend | Cat# 303550; RRID:AB_2860784 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| rVSV-ΔG-GFP | Hastie et al.86 | N/A |

| rVSV-SARS-CoV-2 D614G pseudovirus | Hastie et al.86 | N/A |

| Biological samples | ||

| Covalescent COVID-19 breakthrough donors | LJI Clinical Core | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Brilliant Staining Buffer Plus | BD Biosciences | Cat# 566385; RRID: AB_2869761 |

| LIVE/DEAD Fixable Near-IR Dead Cell Stain APC-eFluor780 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# L34975 |

| Live/DEAD Viability Dye eFluor506 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# 65-0866-14 |

| Live/DEAD Fixable Blue Stain Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# L34962 |

| Synthetic peptides | TC Peptide Lab | https://www.tcpeptide.com |

| Ancestral RBD protein for ELISA | AcroBiosystems | Cat# SPD-C52H1 |

| Delta (B.1.617.2) RBD protein for ELISA | AcroBiosystems | Cat# SPD-C52Hh |

| Omicron BA.1 RBD protein for ELISA | AcroBiosystems | Cat# SPD-C522j |

| Omicron BA.5 RBD protein for ELISA | AcroBiosystems | Cat# SPD-C522r |

| SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid protein | GeneScript | Cat# Z03480 |

| Ancestral RBD protein for flow | BioLegend | Cat# 793906 |

| Delta (B.1.617.2) RBD protein for flow | AcroBiosystems | Cat# SPD-C82Ed |

| Omicron BA.1 RBD protein for flow | AcroBiosystems | Cat# SPD-C82E4 |

| BV421 Streptavidin | BioLegend | Cat# 405225 |

| BV711 Streptavidin | BioLegend | Cat# 405241 |

| BV605 Streptavidin | BioLegend | Cat# 405229 |

| AF647 Streptavidin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# S21374 |

| PerCP Streptavidin | BioLegend | Cat# 405213 |

| Biotin | Avidity | Cat# Bir500A |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| VERO | ATCC | Cat# CCL-81 |

| HEK293T | ATCC | Cat# CRL-3216 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| phCMV-3-SARS-CoV-2 Ancestral Spike | Hastie et al.86 | GenBank: #QHD43416.1 with D614G mutation |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 10 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/; RRID:SCR_002798 |

| FlowJo 10.10 | FlowJo | https://www.flowjo.com/; RRID:SCR_008520 |

| IEDB | Immune Epitope DataBase | https://www.iedb.org; RRID:SCR_006604 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the lead contact, Dr. Alessandro Sette (alex@lji.org).

Materials availability

Epitope pools used in this study will be made available to the scientific community upon request, and following execution of a material transfer agreement, by contacting Dr. Alessandro Sette.

Data and code availability

-

•

The published article includes all data generated or analyzed during this study, and summarized in the accompanying tables, figures, and supplemental materials.

-

•

This study does not generate custom code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and study participant details

Human subjects

Blood samples from healthy adult donors were obtained by donation and collected at the La Jolla Institute Clinical Core in San Diego, California. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee under the La Jolla Institute for Immunology Institutional Review Board (IRB#VD-214). All enrolled patients provided informed consent. The overview of the cohort analyzed is summarized in Table S1. Whole blood was collected from all donors in heparin-coated blood bags and processed as previously described.19 Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by density-gradient sedimentation using Ficoll-Paque (Lymphoprep, and 90% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT) and stored in liquid nitrogen until used in the assays. Each apheresis donation used for epitope identification studies was HLA typed by Murdoch University in Western Australia, an ASHI-accredited laboratory. Typing was performed for the class II DRB1, DQB1, and DPB1 loci and for the class I A, B, and C loci as listed in Table S2.

Method details

Class I T cell predictions and selection

CD8+ T cell responses to SARS2 antigens were identified in 10 individuals after COVID-19 BTI utilizing the AIM assay and previously described SARS2 antigen-specific peptide pools of overlapping 15mers.58 For the positive SARS2 antigens, the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB) class I T cell prediction tool (http://tools.iedb.org/mhci/) was used to identify 9- and 10-mers predicted to bind to the class I HLA-A, B, and C loci for that specific donor for the SARS2 ancestral and variant (according to each donor’s breakthrough infection) sequences. Based on the size of the antigen, the top 4% of peptides with the highest percentile ranks were selected and synthesized for testing. If either an ancestral or variant sequence was predicted but the corresponding variant or ancestral sequence was not, we also synthesized that specific corresponding sequence, regardless of percentile rank.

Preparation of peptide pools and individual peptides

We synthesized 9-, 10- and 15-mer peptides to prepare specific pools and megapools (MP) for detecting T cell responses and epitope identification:

1) To measure protein-specific T cell responses, we synthesized 15-mer peptides overlapping by 10 amino acids covering the entire ancestral SARS2 proteome as previously described.58

2) To measure non-S responses in small blood volumes, we prepared a pool of experimentally defined epitopes, CD4-RE, as previously described.23

3) For S-specific responses to Delta, Omicron BA.1, and BA.5 variants, we synthesized corresponding 15-mer peptides.

4) To evaluate the effect of mutations in the SARS2 proteome, 15-mers spanning mutated regions pertaining to Delta and BA.1 were designed and MPs containing ancestral and variant versions for either Delta or BA.1 were prepared.

5) To identify CD4+ T cell epitopes, the 15-mer peptides overlapping by 10 amino acids and spanning the entire ancestral SARS2 listed in 1) were used to identify protein-specific responses, followed by testing of smaller peptide pools (10 peptides each; mesapools) to then deconvolute positive antigens responses reaching up to the single 15-mers level. In addition, the 15-mers spanning mutated regions pertaining to Delta or BA.1 listed in 2) were used to identify novel CD4+ T cell epitopes in samples with Delta or BA.1 BTI, respectively.

6) To identify CD8+ T cell epitopes the 15-mer peptides overlapping by 10 amino acids and spanning the entire ancestral SARS2 listed in 1) are used to identify protein-specific responses. Class I-specific T cell predictions described in the previous section and based on donor-specific HLA typing and protein reactivity allowed for the design and synthesis of 9-10-mer peptides based on ancestral and Delta or BA.1 sequences to identify also novel CD8+ T cell epitopes in samples with Delta or BA.1 BTI, respectively.

Peptides were synthesized as crude material (TC Lab, San Diego, CA), individually resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 20 mg/mL and Aliquots of pooled by antigen (MPs) or according to pre-defined pools with ten peptides each (mesopools). The MPs required a sequential lyophilization as previously reported87 and were resuspended at 1 mg/mL in DMSO. Mesopools did not require lyophilization and were kept at 2 mg/mL.

Flow cytometry

Activation-induced cell marker assay

The activation-induced cell marker (AIM) assay for epitope identification was performed using PBMCs cultured for 24 h in the presence of SARS2 ancestral and variant megapools (1μg/ml) in 96-well U-bottom plates at a concentration of 1x106 PBMC per well. Equimolar amounts of DMSO were used in triplicate wells to stimulate cells as a negative control. Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) and a cytomegalovirus (CMV) megapool containing CD4 and CD8 MPs (both at 1μg/ml), were used as positive controls. After an incubation period of 24 h at 37°C, 5% CO2 the cells were taken out and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before being stained with an antibody cocktail containing CD8 BUV496 (1:50; BioLegend, clone RPA-T8, Cat# 612942), CD3 BUV805 (1:50; BioLegend, clone UCHT1, Cat# 612895), CD14 V500 (1:50; BioLegend, clone M5E2, Cat# 561391), CD19 V500 (1:50; BioLegend, clone HIB19, Cat# 561121), CD4 BV605 (1:100; BioLegend, clone RPA-T4, Cat# 562658), CD69 PE (1:50; BioLegend, clone FN50, Cat# 555531), OX40 PE-Cy7 (1:50; BioLegend, clone Ber-ACT35, Cat# 350012), CD137 APC (1:25; BioLegend, clone 4B4-1, Cat# 309810), Live/Dead Viability dye eFLuor506 (0.1:100; Invitrogen, Cat# 65-0866-14), brilliant staining buffer and PBS before being refrigerated for 30 min at 4°C, protected from light. For this assay the cells were washed with PBS before being resuspended in 100μL of PBS per well and transferred to acquisition plates to be acquired by a ZE5 cell analyzer (Bio-Rad laboratories) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Combined activation-induced cell marker and intracellular cytokine staining assay

Post-BTI SARS2 samples were tested with a combined activation-induced cell marker and intracellular cytokine staining (AIM+ICS) assay as previously described.9,19 Briefly, cryopreserved PBMCs were thawed in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 5% human AB serum (Gemini Bioproducts) and benzonase [20μL/10mL] (EMD Millipore Corp). Then, 1-2x106 cells per well in 96-well U bottom plates (GenClone) were stimulated for 24 h with 1μg/mL of the following SARS2-derived peptide MPs: Ancestral S, Delta variant S, B.1.1.529 Omicron variant S, BA.4-5 Omicron variant S, and non-S MP CD4-RE, as well as combined megapools of S and non-S Delta or Omicron ancestral peptides and Delta or Omicron variant peptides. In addition, an equimolar amount of DMSO was used as a negative control in a triplicate well, while stimulation with 2μg/mL phytohemagglutinin (PHA) (Roche) was included as the positive control. The cells were blocked with 0.5μg/mL anti-CD40 mAb (Miltenyi Biotec) to retain the CD40L marker expression. The cells were also incubated with CXCR5 BV650 (1:150; BD Biosciences; clone RF882; Cat# 740528), CCR7 PE-Fire640 (1:150; Biolegend; clone G043H7; Cat# 353262), and CD45RA eFluor450 (1:150; Invitrogen; clone H100; Cat# 48045842).

After 20 h of incubation at 37°C, 5% CO2, the cells were incubated for an additional 4 h in the presence of Golgi Plug (containing brefeldin A) (BD Biosciences) and Golgi Stop (containing monensin) (BD Biosciences) to allow the accumulation of intracellular cytokines and CD137 BV421 (1:100; Biolegend; clone 484-1; Cat# 309820) to prevent re-internalization.

After a total of 24 h of cumulative stimulation including cytokines accumulation, membrane staining was conducted by using the following: CD4 BUV395 (1:100; BD Biosciences; clone RPA-T4; Cat# 564724), CD8 BUV496 (1:50; BD Biosciences; clone RPA-T8; Cat# 612942), and CD3 BUV805 (1:100; BD Biosciences; clone UCHT1; Cat# 612895). Furthermore, CD45RA eFluor450 (4:100; Invitrogen; clone H100; Cat# 48045842) and CCR7 PE-Fire640 (4:100; Biolegend; clone G043H7; Cat# 353262) were both used to detect memory T cells; TIM3 BV480 (3:100; BD Biosciences; clone 7d3; Cat# 746771), PD-1 BV711 (4:100; Biolegend; clone EH12.2H7; Cat# 329928), CTLA4 BV786 (3:100; Biolegend; clone BNI3; Cat# 369624) and TIGIT (VSTM3) PE-Dazzle594 (1:100; Biolegend; clone A15153G; Cat# 372716) were used to detect potential exhaustion markers; CXCR5 BV650 (1:100; BD Biosciences; clone RF8B2; Cat# 740528) detected follicular T cells; LIVE/DEAD Fixable NIR stain APC-ef780 (0.02: 100; Invitrogen; Cat# L34975) was used to mark viability in cells and CD14 APC-ef780 (0.25:100; clone 61D3; eBioscience; Cat# 47-0419-4) and CD19 APC-ef780 (1:100; eBioscience; clone HIB19; Cat# 47-0199-42) were both used to exclude monocytes and B cells in the dump channel. CD40L APC (2:100; Biolegend; clone 2431; Cat# 310810) was used to gate the cytokines IFNγ, IL-2, TNFα, and Granzyme B, and AIM+ cells for TFH detection. Activation was measured by the following markers: CD137 BV421 (1:200; Biolegend; clone 484-1; Cat# 309820) and CD69 BV605 (2:100; BD Biosciences; clone FN50; Cat# 562989) for AIM-specific CD8 T cells and CD137 and OX40 PE-Cy7 (0.25: 100; Biolegend; clone Ber-ACT35; Cat# 350012) for AIM-specific CD4 T cells.

Next, fixation of cells was conducted with 4% PFA solution for 10 min at 4°C followed by permeabilization, blocking, and staining for 30 min with the following cytokines: IFNγ FITC (0.2:50; Invitrogen; clone 4S.B3; Cat# 7319-82), IL-2 BB700 (1:50; BD Biosciences; clone MQ1-17H12; Cat#5666405); TNFα PE (0.1:50; Invitrogen; clone Mab11; Cat#12-7349-82) and protease Granzyme B AF700 (0.5:50; BD Biosciences; clone GB11; Cat# 560213). The cells were washed with PBS before being resuspended in 120μL of PBS per well and acquired an Aurora flow cytometry system (Cytek) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Flow-cytometry-based B cell assays

Antigen-specific B cells were detected using B cell probes consisting of SARS2 ancestral and variant S RBDs conjugated with fluorescent streptavidin conjugates, as previously described by our group.88 RBD recombinant proteins used in this study are described in the key resources table. In brief, biotinylated ancestral SARS2 S RBD was incubated with streptavidin in either BV711 (BioLegend, Cat# 405241) or BV421 (BioLegend, Cat# 405225) at a 2.2:1 ratio (4:1 M ratio). One-third of the total streptavidin-fluorophore volume required was added to the biotinylated protein every 15 min on ice and gently mixed by pipetting for a total of 3 additions. The streptavidin-fluorophore conjugates used to tetramerize the SARS2 variant RBDs are listed as follows: Delta (B.1.617.2) RBD BV605 (Biolegend, Cat# 405229), Omicron BA.1 RBD Alexa Fluor 647 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# S21374). Streptavidin PerCP (Biolegend, Cat# 405213) was added to minimize background by gating out nonspecific streptavidin-binding B cells. Ten million PBMCs were placed in U-bottom 96 well plates and stained with a solution consisting of 5 μM biotin (Avidity, Cat# Bir500A), 20 ng of Streptavidin PerCP, and 16.4 ng of RBD probe per stain (=32.8 ng ancestral RBD and 16.4 ng variant RBD per sample) incubated for 1 h at 4°C in the dark. Cells were washed and incubated with surface antibodies diluted in Brilliant Stain Buffer (BD Biosciences, Cat# 566349) for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. Viability staining was performed using the Live/Dead Fixable Blue Stain Kit (Thermo Fisher, Cat# L34962) diluted 1:200 in PBS and incubated at 4°C for 30 min in the dark. Samples were acquired on a Cytek Aurora and analyses were made using Flow Jo v10.x (BD Life Sciences). The frequency of crossreactive variant RBD-binding memory B cells was expressed as a percentage of ancestral RBD memory B cells (Singlets, Lymphocytes, Live, CD3– CD14– CD16– CD56–CD19+ CD20+ CD38int/–, IgD– and/or CD27+ RBD BV711+BV421+).

SARS-CoV-2 ELISA

SARS-CoV-2 serology was performed for all plasma samples collected as previously described (Tarke et al. 2022). Briefly, 1 μg/mL SARS-CoV-2 S ancestral RBD (AcroBiosystems Cat#SPD-C52H1), Delta RBD (AcroBiosystems Cat#SPD-C52Hh), Omicron BA.1 RBD (AcroBiosystems Cat#SPD-C522j), Omicron BA.5 RBD (AcroBiosystems Cat#SPD-C522r), or Nucleocapsid (GeneScript Cat#Z03488) was used to coat 96-well half-area plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat #3690) at 4°C overnight. The next day, plates were blocked at room temperature for 90 min with 3% milk in PBS and 0.05% Tween 20. Heat-inactivated plasma was then added for 90 min at room temperature. Plates were washed and incubated with the conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma Cat#A6029) for 1 h. Plates were washed again and developed with TMB ELISA Substrate Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat#34021). Plates were read on a Spectramax Plate Reader at 450 nm using the software SoftMax Pro. The limit of detection (LOD) was defined as 1:3. The limit of sensitivity (LOS) was established based on uninfected subjects using pre-pandemic plasma.

SARS-CoV-2 PSV neutralization assay

The SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus (PSV) neutralization assay was performed as previously described.19 Briefly, a monolayer of VERO cells (ATCC Cat# CCL-81) was generated by seeding 2.5 x 104 cells in black flat bottom 96-well plates (Corning Cat# 3904). Pre-titrated recombinant virus was incubated with serially diluted heat-inactivated plasma or sera for 1–1.5 h at 37°C, added to confluent VERO cell monolayers, and incubated for 16 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS with 10 μg/mL Hoechst (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat#62249) at room temperature and protected from light for 30 min. Cells were imaged using a Cell Insight CX5 imager to quantify the total number of cells and infected GFP-expressing cells to determine the percentage of infection. Neutralization titers (inhibition dose 50-ID50) were calculated using the One-Site Fit Log IC50 model in Prism 8.0 (GraphPad). We established a calibration factor to determine International Units (IU) based on a comparison between an in-house standard and the WHO international standard for assays using ancestral PSV only. Samples that did not reach 50% inhibition at the lowest serum dilution of 1:20 were considered as non-neutralizing and were calibrated as 10.73 IU/mL.

Recombinant SARS-CoV-2-S pseudotyped VSV-ΔG-GFP were generated as previously described89 by transfecting 293T cells with phCMV-3-SARS-CoV-2 ancestral (D614G) S and collecting supernatants containing rVSV-SARS-2 S.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Data and statistical analyses were performed in FlowJo 10 and GraphPad Prism 8.4 unless otherwise stated. Data plotted in logarithmic scales are expressed as geometric mean or median, as indicated in the figure legends. Statistical analyses are detailed in the figure legends.

For AIM assay all samples were acquired on a Bio-Rad ZE5. The gates for the AIM-positive cells were created according to negative and positive controls per donor. The primary gate was placed around the lymphocyte population, excluding larger cells and debris, followed by the singlet (single cell) gate. T cells were gated for being positive to CD3 and negative for a dump channel including in the same colors CD14, CD19, and Live/Dead staining. The CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ were further gated based on OX40+CD137+ and CD69+CD137+ activation markers respectively.

For the AIM+ICS combined assay, all samples were acquired on a Cytek Aurora (Cytek Biosciences). The same gating strategy was used as described above, including the gates for the AIM populations. The activated OX40+CD137+ and CD69+CD137+ populations were further gated on the exhaustion markers CTLA4, PD-1, TIM3, and TIGIT. To identify cTFH cells, CD3+CD4+ cells were gated for the activation markers OX40+CD40L+ and then CXCR5 expression. For the ICS analysis, the CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ populations were further gated for the co-expression of CD40L (for CD3+CD4+) or CD69 (for CD3+CD8+) with IFNγ, IL-2, TNFα, and Granzyme B.

SARS2 MP-specific T cells were calculated for AIM, ICS, and TFH using the same strategy. The percentages for the triplicate DMSO wells were averaged and then this background was subtracted for each MP-stimulated population. The SI was calculated by the average of the DMSO control wells divided by the percentage of positive cells after MP stimulation. For each gated population, the Limit of Detection (LOD) was determined by the 2-fold upper confidence interval (CI) of the geometric mean, and the Limit of Sensitivity (LOS) was based on the median 2-fold standard deviation of T cell reactivity in the negative DMSO controls. For ICS, the LOS was considered based on the CD40L + IFNγ for CD4+ populations and CD69+IFNγ for CD8+ populations. For the AIM markers, LOD and LOS were calculated based on a control group of unexposed donors. A response was considered positive if the SI was greater than 2 and the background subtracted value was greater than the LOS.

T cell epitope identification analysis strategy

SARS2 MPs pooled per protein were first tested by the AIM assay in the BTI Epitope ID cohort. Counts of AIM-positive cells were normalized to 1x106 total CD4+ or CD8+ T cells based on the count of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells in each sample. If a pool per protein had a positive response over 200 CD4+ AIM+ cells in a donor, then the intermediate mesapools were tested for the ancestral and variant sequences. Positive mesapools were deconvoluted by testing the individual peptides. If a pool per protein had a positive response over 200 CD8+ AIM+ cells in a donor, the mesapools corresponding to the predicted ancestral and variant 9mer and 10mers for that protein and that donor’s HLA were tested. Positive mesapools were deconvoluted by testing the individual peptides. For some donors, multiple nested class I peptides were positive for the same protein and allele. In these cases, the epitope with the highest magnitude of response was determined to be the optimal epitope, as previously described.58 Nested epitopes corresponding to different donors or alleles were conserved as separate epitopes.

Acknowledgments

This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under contract no. 75N93021C00016 to A.G. and contract no. 75N9301900065 to A.S. A.T. was supported by NIH T32AI125179. This work was funded by NIH NIAID award AI142742 (Cooperative Centers for Human Immunology) (S.C. and A.S.). We thank Gina Levi and the LJI clinical core for assistance in sample coordination and blood processing.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, S.C., A.G., and A.S.; methodology, A.T., P.R.-R., T.A.P.N., Y.L., V.M., B.G., N.B., L.S., L.A., Z.Z., R.d.S.A., and J.D.; Formal analysis, A.T., P.R.-R., T.A.P.N., Y.L., V.M., B.G., N.B., L.S., and L.A.; investigation, A.T., P.R.-R., J.D., and A.G.; project administration, A.F., A.G., and A.S.; funding acquisition, A.G. and A.S.; writing, A.T., P.R.-R., J.D., S.C., A.G., and A.S.; supervision, S.C., A.G., and A.S.

Declaration of interests

A.S. is a consultant for AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Calyptus Pharmaceuticals Inc, Darwin Health, EmerVax, EUROIMMUN, F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd, Fortress Biotech, Gilead Sciences, Granite bio., Gritstone Oncology, Guggenheim Securities, Moderna, Pfizer, RiverVest Venture Partners, and Turnstone Biologics. A.G. is a consultant for Pfizer. S.C. has consulted for GSK, JP Morgan, Citi, Morgan Stanley, Avalia NZ, Nutcracker Therapeutics, University of California, California State Universities, United Airlines, Adagio, and Roche. L.J.I. has filed for patent protection for various aspects of T cell epitope and vaccine design work.

Published: May 22, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101583.

Contributor Information

Shane Crotty, Email: shane@lji.org.

Alba Grifoni, Email: agrifoni@lji.org.

Alessandro Sette, Email: alex@lji.org.

Supplemental information

Refers to Figure 5 and Tables S1 and S2. List of class II (for CD4) and class I (for CD8) epitopes identified in 5 BTI Delta donors and 5 BTI Omicron BA1 donors (cohort 3, Table S1)

References

- 1.Organization, W.H. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2020. https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.Malato J., Ribeiro R.M., Leite P.P., Casaca P., Fernandes E., Antunes C., Fonseca V.R., Gomes M.C., Graca L. Risk of BA.5 Infection among Persons Exposed to Previous SARS-CoV-2 Variants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;387:953–954. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2209479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.COVID-19 Forecasting Team Past SARS-CoV-2 infection protection against re-infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2023;401:833–842. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(22)02465-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magen O., Waxman J.G., Makov-Assif M., Vered R., Dicker D., Hernán M.A., Lipsitch M., Reis B.Y., Balicer R.D., Dagan N. Fourth Dose of BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine in a Nationwide Setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;386:1603–1614. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2201688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arbel R., Sergienko R., Friger M., Peretz A., Beckenstein T., Yaron S., Netzer D., Hammerman A. Effectiveness of a second BNT162b2 booster vaccine against hospitalization and death from COVID-19 in adults aged over 60 years. Nat. Med. 2022;28:1486–1490. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01832-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]