Abstract

Menopause experiences and care vary widely because of biological, sociodemographic, and sociocultural factors. Treatments for troublesome symptoms are not uniformly available or accessed. Intersectional factors may affect the experience and are poorly understood. Disparities across populations highlight the opportunity for a multifaceted equitable approach that includes patient-centered care, education, and policy change.

Menopause experiences and care vary widely because of biological, sociodemographic, and sociocultural factors. Treatments for troublesome symptoms are not uniformly available or accessed. Intersectional factors may affect the experience and are poorly understood. Disparities across populations highlight the need for a multifaceted equitable approach that includes patient-centered care, education, and policy change.

Main text

Menopause is usually a typical reproductive stage for individuals assigned female at birth (henceforth referred to as “women”), generally occurring around age 51 years.1 However, it often happens earlier in women from low- and middle-income countries, which may have implications for the risk of chronic disease such as osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease.1 Menopause may be spontaneous or iatrogenic due to bilateral oophorectomy or cancer treatment such as chemotherapy or radiation. While many women navigate menopause without seeking medical treatment, around 60%–80% experience vasomotor symptoms that can last for more than 7 years2 and impact their quality of life.1 Effective treatments are available for vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and night sweats) and vaginal dryness. Menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) reduces vasomotor symptoms by around 85%, and some nonhormonal treatments may also be effective but less so than MHT.1 Psychological therapies, including cognitive behavioral therapy and hypnosis, have a small to moderate effect, with additional benefits for sleep, mood, fatigue, and quality of life.1 However, these treatments are not equally accessed across socioeconomic groups and race.3,4 Other circumstances influencing menopause-related health outcomes include geography (e.g., access to health care) and healthcare provider perceptions and attitudes (e.g., mistaken belief in the long-term benefits of MHT).5 In addition, factors driving treatment use are menopause awareness, perceptions, and education; perceived health status; help-seeking behaviors; preference for alternative management strategies; and stigma.5 How these factors interplay to impact treatment access and uptake is not well understood.

Symptoms and treatment

Vasomotor symptoms are the leading patient priority for treatment.1 Bother and interference due to vasomotor symptoms drive treatment seeking more than frequency or severity does.1 Other symptoms commonly associated with menopause include muscle and joint pain, sleep disturbance, and genitourinary issues such as vaginal dryness. Here, we focus on how sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and gender disparities impact the experience and management of vasomotor symptoms.

The nature, perceived severity, and impact of vasomotor symptoms are mediated by several factors. The intersecting structural systems of society, weathering (i.e., prolonged exposure to stressors that worsen health issues), and social determinants of health affected by race, ethnicity, disability, educational level, employment, economic status, residence, relationship status, social supports, parity, body mass index, and lifestyle factors modify the severity and duration of vasomotor symptoms.6 Additional influences that may affect access to, and uptake of, pharmacological and psychological treatments for vasomotor symptoms include sexuality, chronic health conditions, attitudes, and health literacy.7,8,9 How these intersect to affect the experience of menopause is uncertain. For example, a US-based study reported that African American women experience more frequent and prolonged vasomotor symptoms and are more bothered by them compared with White American women, while Chinese American and Japanese- American women describe fewer vasomotor symptoms than White, African American, or Hispanic American women.2,4 This suggests that racial factors impact on symptom experience.

MHT is used more frequently and for longer periods in White women who generally have relatively higher education and socioeconomic status.1,3 Data from the United States, China, and Iran report that higher educational attainment, in either women or their partners, is associated with less severe vasomotor symptoms—with educational programs having the potential to improve both the psychological and physical domains relating to menopause-related quality of life.4,8 This may suggest that higher education leads to increased awareness and empowerment regarding seeking help or that it may reflect intersectional effects, such as different symptom experiences according to race. Intersectionality is the interconnected nature of social categorizations, or the overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage. In this example, intersectionality may affect how educational attainment influences the work or home environment or access to support and care. Marginalized groups, including sexually diverse and indigenous populations, often report knowledge gaps in understanding menopause symptoms and treatment options.7 This may be due to the effect of stigma and discrimination on their health experiences. There is a paucity of health equity research that examines whether disparities in menopause care are due to biases in healthcare provision, differences in patient factors (such as treatment-seeking behaviors), patient choice, or access to care.3

Most menopause research has been conducted in high-income countries, with cisgender, White women. Less is known about the efficacy and acceptability of treatment options in less-privileged or disadvantaged women. In particular, the short- and long-term safety of treatments such as MHT in diverse groups is poorly understood and may be of direct clinical importance.7 For example, the risk of stroke is tripled among African American women aged 50–60 years.10 While MHT is reported to have a minimal impact on stroke risk in White women under the age of 60, its effects on stroke risk in women from other racial groups are unknown.10

In considering intersectionality, multiple factors contribute to menopause symptoms and treatment utilization, but limited research exists on the hierarchy and weight of attribution of these factors to women’s experiences. Those who are more disadvantaged are more likely to experience poor health throughout their lives, and the effects on poor health (across all health areas) accumulate. This is likely to also apply to the experience of menopause. Few studies have examined how factors that influence health equity collectively affect the occurrence, impact, or treatment of vasomotor symptoms. A secondary analysis of data from 1,027 midlife women in the United States explored the collective impact of the interaction between frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms and other characteristics across four groups: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic African American, non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic women.11 The authors found that both country of birth and employment cumulatively contributed to the frequency and severity of vasomotor symptoms and differed across racial groups, illustrating that these factors interact to influence symptoms. Research exploring these relationships can improve the understanding of the combined influence of the factors that affect menopause.

Creating equity in menopause care

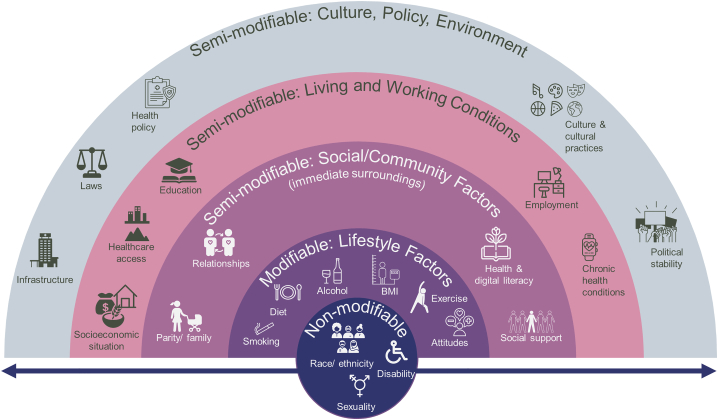

The World Health Organization report on “Closing the gap in a generation” (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1) states that to achieve equity, all women can have a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of health. In the context of menopause, clinicians can recognize the diversity and complexity of symptoms experienced during the menopause transition, which can be considered using a social health model (Figure 1). This framework illustrates that to provide equitable care, interventions could come at different levels—addressing modifiable factors at the individual level and advocating for structural changes for the semi-modifiable and non-modifiable factors. Potential approaches to address these factors are described below.

Figure 1.

How menopause can be viewed in the context of a social health model

Using a patient-centered approach to clinical care

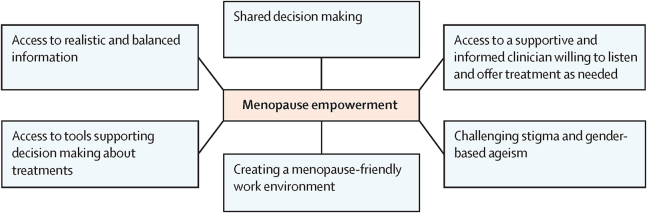

A patient-centered, social health model considers where disadvantages may have an impact on both the nature or symptoms and the appropriate management strategy to facilitate patient-informed care. Clinicians could be aware of and sensitive to the cultural beliefs, norms, and preferences about menopause. They can also understand the importance of gender in making patients feel included and comfortable during clinical encounters and can tailor their care approaches accordingly. For example, a study of menopause experiences among Vietnamese migrant women in Australia suggests that primary care physicians proactively discuss menopause since women may be reluctant to raise the topic.12 Clinicians could acknowledge and validate the unique experiences of patients from marginalized groups, who may feel “invisible” or that their experiences are dismissed since they are not represented in the available data.7 Personal choice (often based on personal values, opinions, and perspectives) around management of menopause will also drive healthcare use and adherence to treatment. Alignment of value management strategies may improve well-being and quality of life.1 For example, some Asian American groups tend to use complementary and alternative approaches to symptom management more than they use MHT and report lower quality of life with MHT.1 This could indicate less severe vasomotor symptoms but could also reflect personal preferences.1,7,12 Using an empowerment model for menopause (Figure 2) can help to address many of these issues.1 Empowering individuals to actively participate in decision-making regarding their healthcare enables them to assert their preferences and needs, promoting equitable treatment outcomes.

Figure 2.

An empowerment model for managing menopause

Reprinted from The Lancet, vol. 403, Hickey et al., Copyright 2024, with permission from Elsevier.1

Evidence gaps

To understand why some groups are more likely to receive care or use different treatment options for vasomotor symptoms, researchers could investigate the underlying drivers. For example, some women may not need medical care or treatment.1 Some may not seek medical assistance because they believe that menopause is a natural process of aging.9,13 Others may be reluctant to seek treatment despite experiencing bothersome symptoms.13 A deeper understanding of these factors could lead to more equitable and customized care and interventions for menopause that will meet personal needs.

Increasing menopause education

Comprehensive health education programs can empower women with knowledge about menopause and available support services.1 However, accessing evidence-based information about menopausal symptoms and the effectiveness of various treatments produced without commercial bias is often difficult. Information can also be culturally accessible. Examples include https://mymenoplan.org/ and https://wandcre.org.au/menopause-and-healthy-living/. Specifically, providing decision support for treatment options could be particularly helpful.1 There is also an opportunity for better training of all healthcare professionals regarding menopause and management of troublesome symptoms.

Changing attitudes toward menopause

Traditionally, much research in women’s health has predominantly concentrated on reproductive health, often overlooking postmenopausal women. This narrow focus can contribute to negative attitudes toward aging and menopause, suggesting that these life stages are less worthy of attention and care. Attitudes toward menopause relate to the symptom experience.8 In societies where aging in women confers respect, women report fewer troublesome symptoms.8 While is it unclear whether positive attitudes result in better management of symptoms or whether fewer symptoms result in positive attitudes, challenging prevalent gendered agism may confer benefits for older women and society in general.1

Shifting perspectives requires a feminist approach that captures women’s realities and voices, acknowledging the multiple and intersecting factors that can drive inequalities in practice and challenging the structures that determine funding and reporting for research. A Lancet Commission on gender and global health (https://genderandhealthcommission.org/) is underway, guided by a feminist, intersectional, decolonial, and political approach that aims to achieve shared global health equity goals. This approach fits well in the context of advocating for change in attitudes at all levels (individual, health system, and policy).

Workplace interventions

Workplace environments can impact the menopause experience. For example, lack of flexibility around work hours and place, limited access to toilets, or nonbreathable uniforms can increase the burden of vasomotor symptoms.14 The nature of employment is often influenced by socioeconomic status, gender, geography, and education, meaning that disadvantaged, minoritized groups may be further disadvantaged at work. For example, people from ethnic minority backgrounds may face systemic barriers, particularly if educational and network disparities can have an impact on the ability to secure high-paying positions. Addressing workplace factors likely to affect disadvantaged women may help create an inclusive work culture, particularly for those with lower socioeconomic status or less job security who may currently be less able to discuss problems with leadership.14 However, there is a gap in the evidence around workplace interventions for those experiencing troublesome menopausal symptoms.

Focusing research on patient priorities

Understanding the key knowledge gaps for those experiencing menopause and their healthcare providers can inform research to deliver more equitable care, interventions, and resources. The Menopause Priority Setting Partnership (MAPS, https://obgyn.uchicago.edu/research/menopause-priority-setting-partnership) is addressing the discrepancy between what researchers choose to study and what patients and healthcare providers want to know. The priority research gaps identified by MAPS will be used to set a new, patient-focused research agenda.

Technology

Harnessing technology, such as digital health platforms and telemedicine, can potentially improve access to menopause-related healthcare, particularly for individuals in remote or underserved areas who have access to technology.15 By leveraging technological solutions, healthcare providers may overcome geographical barriers and deliver care more efficiently. For areas that lack access to technology, there is a pressing opportunity to enhance and guarantee access to health technologies.

Increased diversity in global menopause health leadership

A key element influencing gender equity and equality in health is representation. Opportunities for women are limited by gender bias and discrimination in the health workforce. Additionally, caregiving responsibilities can limit opportunities for women and diverse groups to reach leadership positions. Bullying and harassment can further hamper career development. A cultural shift can ensure that diverse leadership is supported and retained.

Policy changes

Socioeconomic circumstances may be modifiable by policies at the local, national, and global levels. Interventions can address structural barriers by targeting education about menopause, addressing financial disparities, and improving access to care. For example, education programs can empower women to make informed health decisions. Some women report that menopause can be stigmatizing (as it may be viewed as an indicator of aging), and changing societal attitudes around aging in women, particularly in the context of menopause, might mitigate this.6 In general, prioritizing inclusive language and practices in healthcare could mitigate the reluctance of marginalized communities to seek medical care due to fears of discrimination and mistreatment.7,9 This also applies for menopause care. Treatment costs can be a barrier for those with low incomes, but subsidized access to healthcare and effective treatments can increase accessibility.7 For example, the United Kingdom has recently endorsed 12 months of low-cost MHT. More accessible care, such as women’s health hubs (https://www.rcgp.org.uk/representing-you/policy-areas/womens-health-hub-model), may provide a safe space for women to seek menopause care. Upskilling primary care providers to manage menopause may increase access to care. Legislation may also protect women experiencing menopausal symptoms at work. In the United Kingdom, discrimination due to menopause falls under the Equality Act 2010, and employers have an obligation to provide safe working conditions for women experiencing menopausal symptoms (https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents).

Conclusion

Although all women who reach a certain age will eventually undergo menopause, their experience may be profoundly affected by intersectional socioeconomic and sociocultural factors. Although effective treatments are available, their access and utilization across diverse groups are considerably unequal. Addressing these issues requires a multifaceted approach. Policies at local, national, and global levels can shape better outcomes by addressing structural barriers and fostering interventions that enhance women’s knowledge, train providers, and improve access to treatment for those who want it. Financial disparities in access to care can also be addressed. By leveraging a patient-centered, culturally sensitive approach and considering the modifiable social factors, the medical community can foster more equitable menopause care. This may improve health outcomes and enhance quality of life. It is essential to understand how sociodemographic, socioeconomic, and sociocultural factors affect the symptoms of menopause as well as the safety and efficacy of its treatments. Future research can address how interventions can best meet the diverse needs of the populations they are intended to serve. Ultimately, an equitable approach to menopause care requires a concerted effort from healthcare providers, researchers, policymakers, and society at large to ensure that every individual can receive support and care.

Acknowledgments

M.P. is partially supported by a Rowden White grant from the University of Melbourne. M.H. is supported by an NHMRC investigator grant. The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the United States Government.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and M.H.; writing – original draft, M.P. and M.H.; writing – review & editing, M.P., M.H., T.L.J., and N.E.A.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests

References

- 1.Hickey M., LaCroix A.Z., Doust J., Mishra G.D., Sivakami M., Garlick D., Hunter M.S. An empowerment model for managing menopause. Lancet. 2024;403:947–957. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(23)02799-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avis N.E., Crawford S.L., Greendale G., Bromberger J.T., Everson-Rose S.A., Gold E.B., Hess R., Joffe H., Kravitz H.M., Tepper P.G., et al. Duration of menopausal vasomotor symptoms over the menopause transition. JAMA Intern. Med. 2015;175:531–539. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hillman S., Shantikumar S., Ridha A., Todkill D., Dale J. Socioeconomic status and HRT prescribing: a study of practice-level data in England. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2020;70:e772–e777. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X713045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Khoudary S.R., Greendale G., Crawford S.L., Avis N.E., Brooks M.M., Thurston R.C., Karvonen-Gutierrez C., Waetjen L.E., Matthews K. The menopause transition and women's health at midlife: a progress report from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Menopause. 2019;26:1213–1227. doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000001424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richard-Davis G., Singer A., King D.D., Mattle L. Understanding Attitudes, Beliefs, and Behaviors Surrounding Menopause Transition: Results from Three Surveys. Patient Relat. Outcome Meas. 2022;13:273–286. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S375144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis Johnson T., Rowland L.M., Ashraf M.S., Clark C.T., Dotson V.M., Livinski A.A., Simon M. Key Findings from Mental Health Research During the Menopause Transition for Racially and Ethnically Minoritized Women Living in the United States: A Scoping Review. J. Womens Health. 2024;33:113–131. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2023.0276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cortés Y.I., Marginean V. Key factors in menopause health disparities and inequities: Beyond race and ethnicity. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 2022;26 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Namazi M., Sadeghi R., Behboodi Moghadam Z. Social Determinants of Health in Menopause: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Womens Health. 2019;11:637–647. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.S228594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zou P., Waliwitiya T., Luo Y., Sun W., Shao J., Zhang H., Huang Y. Factors influencing healthy menopause among immigrant women: a scoping review. BMC Wom. Health. 2021;21:189. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01327-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiménez M.C., Manson J.E., Cook N.R., Kawachi I., Wassertheil-Smoller S., Haring B., Nassir R., Rhee J.J., Sealy-Jefferson S., Rexrode K.M. Racial Variation in Stroke Risk Among Women by Stroke Risk Factors. Stroke. 2019;50:797–804. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.117.017759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Im E.O., Yi J.S., Chee W. A decision tree analysis on multiple factors related to menopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2021;28:772–786. doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000001798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanzel K.A., Hammarberg K., Nguyen T., Fisher J. ‘They should come forward with the information’: menopause-related health literacy and health care experiences among Vietnamese-born women in Melbourne, Australia. Ethn. Health. 2022;27:601–616. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2020.1740176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sydora B.C., Graham B., Oster R.T., Ross S. Menopause experience in First Nations women and initiatives for menopause symptom awareness; a community-based participatory research approach. BMC Wom. Health. 2021;21:179. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01303-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodrigo C.H., Sebire E., Bhattacharya S., Paranjothy S., Black M. Effectiveness of workplace-based interventions to promote wellbeing among menopausal women: A systematic review. Post Reprod. Health. 2023;29:99–108. doi: 10.1177/20533691231177414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rachagan N., Szabo R.A., Rio I., Rees F., Hiscock H.M., Hickey M. Video telehealth to manage menopausal symptoms after cancer: a prospective study of clinicians and patient satisfaction. Menopause. 2023;30:143–148. doi: 10.1097/gme.0000000000002101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]