The current British government has created five national agencies to regulate the NHS. These new arrivals are simply additions to an already crowded regulatory landscape. But, if politicians can be persuaded to let go, the new regulators of the NHS could provide a genuinely new approach to improving performance and management

During the past four years the British government has created five new national agencies to regulate the NHS in England (box).1–4 The government has moved away from using markets, competition, and contracting to manage performance in the NHS. But it has been unwilling to rely on traditional bureaucratic structures to exert control, and has turned increasingly to regulation.

In this article, I describe how and why organisational regulation in the NHS in England has grown in recent years. I examine how regulation was used in the NHS in the past and describe the characteristics of the new regulatory agencies. Finally, I use information from the wider literature on regulation to examine the regulatory model adopted by these new agencies and to explore what they might learn from regulation in other settings.

Summary points

Over the past 20 years, regulation has increased in Britain's private and public sectors

In the past four years the British government has created five new national agencies to regulate the NHS

The new agencies could be the start of a new approach to improving performance and management in the NHS

The new agencies could learn from regulators in other sectors and adopt a responsive approach to regulation

New national agencies to regulate the NHS

National Institute for Clinical Excellence

Commission for Health Improvement

Modernisation Agency

National Patient Safety Agency

National Clinical Assessment Authority

Defining regulation

Regulation is “sustained and focused control exercised by a public agency over activities which are valued by a community.”5 The key features of regulation are that it involves a third party—the regulator—in market transactions and interorganisational relationships and that it places responsibility for overseeing performance with a single entity—the regulator. Economists see regulation largely as a remedy for market failure.6,7 However, as the definition suggests, regulation is also often used to achieve wider social goals—equity, diversity, or social solidarity—and to hold powerful corporate, professional, or social interests to account.8 Few areas of modern society have not been touched by regulation, but in many countries healthcare organisations are subject to quite intensive regulation.

Why is regulation increasing?

The recent rise of regulation in the NHS is part of the growth of the “regulatory state”9 or “audit society”10 in the British private and public sectors over the past 20 years. Between 1979 and 1997, despite being overtly committed to deregulation, the Conservative administration created a host of new regulatory agencies—many to oversee newly privatised industries.11 The Conservatives increasingly used regulation to manage the performance of public sector organisations—creating or strengthening regulatory agencies for schools, higher education, social care, and many other public services.12 The costs of regulating the public sector in the United Kingdom in 1995 were estimated to be between £770m and £1bn (about 0.3% of public expenditure). At least 135 different bodies regulated public sector organisations, and the cost of regulation doubled, or even quadrupled, between 1976 and 1995.13

Reasons for growth in regulation

Regulation of the public sector in the United Kingdom has grown in part because of changes to the management and structure of public sector organisations. The “new public management” gave organisations greater autonomy, placed them at arm's length from the government, separated purchasing and providing functions, and increased competition.14 These changes also brought new accountabilities and controls, including more regulation. Increasing regulation also results from a shift in how society holds public services to account—from a reliance on accountability through elected central and local governments to a desire for more direct and extensive oversight.15

In creating these new regulatory agencies the government may simply be seeking new ways to get things done in public sector organisations. Regulation is intended to be used alongside (not instead of) other mechanisms, such as traditional bureaucratic control and limited competition.16 From the government's perspective, the quasi-independent status of regulatory agencies distances politicians from difficult issues or unpleasant decisions. The responsibility for problems is shifted to the regulator, but the reach and scope of governmental control is retained, or even increased.

Existing regulation in the NHS

The NHS has a long and diverse tradition of regulation. Most NHS organisations already report to a host of bodies who regulate or review what they do and how they do it (table 1). Current regulators vary widely in their statutory authority, powers, scope of action, and approach. The resulting mosaic of regulatory arrangements is highly fragmented and some roles are duplicated. Most of the regulators shown in table 1 deal with a single facet of the NHS organisations that they regulate—health and safety, medical education, the administration of mental health legislation, etc—rather than the organisation as a whole. The regulators' demands on the NHS can conflict or overlap because arrangements for regulators to share information and systems to coordinate fieldwork are few and far between. Organisations in the NHS often complain of “inspectorial overload.”17 Even if several agencies had serious concerns about the performance of a particular organisation, it is unlikely that any one of them would be able to see the bigger picture of organisational failure.

Table 1.

Types of regulators working in and with the NHS in England

| Field of interest | Regulator with statutory authority and powers | Regulator without statutory authority, but with some formal powers | Regulator without statutory authority or formal powers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generic | Audit Commission National Audit Office Health and Safety Executive Equal Opportunities Commission Data Protection Registrar | British Standards Institution ISO 9000 quality management standard | Chartermark scheme Investors in People (human resources accreditation scheme) |

| Health care | Mental Health Act Commission Health Service Commissioner | Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts Medical Royal Colleges accreditation of training for junior medical staff National External Quality Assessment Schemes for pathology laboratories Clinical Pathology Accreditation scheme | Health Quality Service (accreditation scheme) Royal College of General Practitioners (practice accreditation scheme) National confidential enquiries |

The creation of five new agencies for regulating the NHS does nothing to resolve this confusion—the new arrivals are simply additions to the already crowded regulatory landscape. The remit and scope of the new regulators overlaps with those of existing regulators and each other, although the creation of an overarching body to coordinate the NHS's regulatory agencies has been proposed.18

The new regulators of the NHS

Table 2 summarises the characteristics of the five new regulatory agencies for the NHS in England. Not all see themselves as regulators—perhaps because the term has negative connotations—but they do all fit the definition of regulation.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the five NHS regulators created by the British government between April 1999 and April 2001

| Name | Who it regulates | Date established | Annual budget (£) | Mission or purpose | How it works | What it is |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Institute for Clinical Excellence (www.nice.org.uk) | NHS in England and Wales | Apr 1999 | 10.6m (2001-2002) | To provide patients, health professionals, and the public with authoritative, robust, and reliable guidance on current “best practice” | Uses teams of experts to review health technologies and interventions and produce guidance which is then disseminated | A special health authority, set up by statutory instrument (SI 1999 Nos 220 and 2219) |

| Commission for Health Improvement (www.chi.nhs.uk) | NHS in England and Wales | Nov 1999 | 24.5m (2001-2002) | To help improve the quality of patient care by assisting the NHS in addressing unacceptable variations and to ensure a consistently high standard of patient care | Undertakes clinical governance reviews of all NHS organisations every 4 years; monitors implementation of guidelines from NICE, national service frameworks, etc; investigates major system failures within the NHS | A non-departmental public body established by the Health Act 1999 |

| Modernisation Agency (www.modernnhs.nhs.uk) | NHS in England | Apr 2001 | 54.6m (2001-2002) | To help the NHS bring about improvements in services for patients and contribute to national planning and performance improvement strategies | Encompasses existing national patient action team; primary care development team; collaboratives programme; leadership centre; beacon programme; and clinical governance support unit | Part of the Department of Health |

| National Patient Safety Agency (www.npsa.org.uk) | NHS in England (at present) | Jul 2001 | 15m (2002-2003) | To collect and analyse information on adverse events in the NHS, assimilate safety information from elsewhere, learn lessons and feed back to the NHS, produce solutions, set national goals and establish mechanisms to track progress | Will establish and operate a new, mandatory national system for reporting adverse events and “near misses,” and provide national leadership and guidance on patient safety and adverse events | A special health authority set up by statutory instrument (SI 2001 No 1743) |

| National Clinical Assessment Authority (www.ncaa.nhs.uk) | NHS in England (at present) | Apr 2001 | 10.1m (2002-2003) | To provide a support service to health authorities and hospital and community trusts who are faced with concerns over the performance of an individual doctor | Deals with concerns about doctors in difficulty by providing advice, taking referrals and carrying out targeted assessments where necessary | A special health authority set up by statutory instrument (SI 2000 No 2961) |

In some respects, the new regulators are different from the existing regulatory agencies (table 1):

They are well resourced organisations, for whom regulation is the primary mission, rather than one function among many that they undertake

Their broad remit to oversee NHS organisations is not limited to particular service areas or functions, like that of many of the existing regulators

They are all essentially agents of the government—all are accountable to the Department of Health and have their boards appointed by the secretary of state. They have little independence and, taken together, represent a significant strengthening of central government's control of the NHS

Perhaps most importantly, these new regulators are all concerned primarily with the clinical quality of healthcare. Past regulation has often focused on more peripheral administrative and managerial matters, not on clinical practice.

Regulatory paradigm: deterrence or compliance

Regulatory agencies tend to subscribe to one of two paradigms of regulation—deterrence or compliance (table 3).19 The deterrence model assumes that the organisations being regulated are “amoral calculators”20 that put profit or other motivations before the public good, will ignore regulations if it pays them to do so, and so have to be forced to behave well by strict regulation, demanding standards, and tough enforcement. In comparison, the compliance model assumes that the organisations being regulated are fundamentally good hearted and well meaning, and they would generally do the right thing if they could. Regulators provide support and advice, and they are understanding and forgiving of lapses when they occur.

Table 3.

Comparison of deterrence and compliance models of regulation

| Feature | Deterrence | Compliance |

|---|---|---|

| Setting in which model most often found | Where regulator deals with a large number of small organisations, heterogeneous in nature, and with a strong business culture (private sector, competitive, profit maximising, risk taking, etc) | Where regulator deals with a small number of large organisations, homogeneous in nature, and with a strong ethical culture (public sector, professionalism, voluntarism, not for profit organisations, etc) |

| Regulator's view of regulated organisations | Amoral calculators, out to get all they can, untrustworthy | Mostly good and well intentioned, if not always competent |

| Regulated organisations' view of regulatory agency | Policeman, enforcer—feared and often respected, usually disliked | Consultant, supporter—not seen as a threat or problem, may be respected and liked |

| Temporal perspective | Retrospective (identify, investigate and deal with problems when they have happened) | Prospective (aim to prevent problems occurring through early intervention and support) |

| Use of regulatory standards and inspection | Many detailed and explicit written standards, often with statutory force; approach to inspection and enforcement highly focused on standards | May have detailed written standards and policies often accompanied by guidance on implementation; standards play a less prominent part in interactions with regulated organisations |

| Enforcement, and use of sanctions or penalties | Part of routine practice, valued for deterring penalised and other regulated organisations | Seen as the last resort, used only when persuasion exhausted |

| Provision of advice and support to regulated organisations | Not part of the regulator's role—seen as risking regulatory capture and having conflict of interest with policing and punishing role | Essential part of regulator's role—valued as opportunity to understand, build cooperative relationships, and influence performance |

| Relationship between regulator and regulated organisations | Distant, formal, and adversarial | Close, friendly, and cooperative |

| Costs of regulation | High cost to regulator and regulated organisations in inspection and enforcement | Lower costs, particularly in inspection and enforcement, though costs to regulator of providing advice and support to regulated organisations can be higher |

| Likely advantages | Regulated organisations pay attention to regulator, take it seriously, and respond readily to its initiatives | Regulators and regulated organisations work together on improvement and collaborate effectively; costs of regulation are minimised |

| Likely disadvantages | Creative compliance, resistance, and lobbying by regulated organisations are likely to subvert purpose of regulation. Very high costs associated with sustained inspection and enforcement | Regulation may lack teeth and may be seen as weak, with limited ability to make unwelcome changes happen in regulated organisations. Regulator may be seen as too close to or allied with the organisations it regulates |

In practice, regulated organisations vary widely in their motivations. Although regulators sometimes adopt a mixed or differentiated approach that takes account of such variations, they are often forced by legislative, political, or other pressures to use a particular regulatory style, regardless of its appropriateness. In the past, regulators in the NHS (and in the United Kingdom generally) have adhered to a model of regulation largely based on compliance.21 However, the approach used in the public sector in the United Kingdom has been increasingly oriented towards deterrence.22 This change seems to be favoured by politicians, the media, and the public. The new healthcare regulators may face pressures to use a deterrence style of regulation, whether or not it is effective.23

Regulation and performance improvement: lessons for new NHS regulators

Most published work deals with regulation in settings outside healthcare24–26 or with general regulatory theory,27–29 but the amount of literature on healthcare regulation is increasing.30–32 What advice can this literature give to the new NHS regulators?

Firstly, it seems that effective regulation is “responsive”28—a regulatory agency should recognise and respond to the diversity of organisations it regulates, making its regulatory regime adapt to how individual organisations behave. The regulator eschews “one size fits all” policies—inspecting every organisation in the same way, at the same frequency, using the same standards—in favour of a more flexible and graduated approach that is constantly adapted to the content and outcome of each regulatory encounter. The deterrence and compliance models set up a false dichotomy—an effective regulator uses both approaches at different times, with different organisations, to meet different objectives.

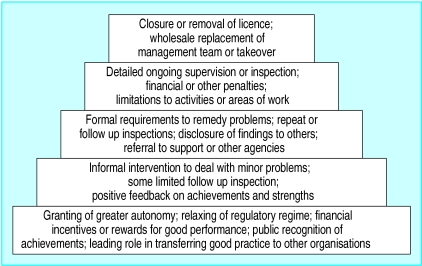

Secondly, the responsive approach means that the regulator needs to have a wide range of regulatory interventions—both incentives and sanctions—and to use them appropriately (figure). Most regulatory activity should take place at the lower levels of the pyramid—the methods at the top should need to be used only rarely, but they need to be available to sustain the integrity and credibility of the regulatory system. Regulators should be able to move freely up and down the hierarchy of methods. Legislation or policies that force regulators to use particular methods or levels are likely to reduce their effectiveness.

Thirdly, effective regulators work with and through other stakeholders in the organisations they regulate, rather than treating the relationship between them and the organisation as bilateral. This approach—tripartism—involves designing regulatory methods to involve groups such as patients, consumers, staff, and partner organisations in regulation. Regulators may seem to be powerful, but they actually have very limited resources, and they can never oversee more than a tiny proportion of regulated activities. Tripartism allows them to extend their oversight by using other stakeholders as informants and agents for change.

Finally, regulatory agencies need to balance independence and accountability. Regulators need to be independent to maintain their credibility, to allow them to act impartially as an “honest broker” when they need to, and to enable them to take actions that may be unpopular with some stakeholders. On the other hand, regulators should be held accountable for what they do and for the effects of regulation, and all stakeholders need to be involved, to some extent, in accountability arrangements to avoid regulation being captured by one group or another. For regulatory agencies that are part of government, a mechanism for distancing them from their political masters, while still maintaining appropriate accountability, is needed.

Conclusions

The rise of regulation in the NHS seems, at first sight, to represent a long term strengthening of central government's control of managerial and clinical practice. The new regulators are government agencies, headed by ministerial appointments. The Department of Health provides their budgets and enforcement powers. Their creation could allow a kind of centralised micromanagement, in which there is less and less scope for local variation, to develop.

However, if the politicians can be persuaded to let go, the new regulators of the NHS could provide a genuinely new approach to improving performance and management. A longstanding tradition makes ministers directly accountable for everything that happens in the NHS; this could be replaced by a more indirect and distanced relationship, in which managed regulation by intermediate and quasi-independent organisations would play a large part. In that environment, the new regulatory agencies could adopt a more responsive approach to regulation—learning from the experience of regulation in other settings and focusing regulation on delivering real improvement for patients.

Figure.

Hierarchy of regulatory enforcement28

Footnotes

Funding: KW was supported by the Commonwealth Fund, a private independent foundation based in New York City. The views in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Commonwealth Fund, its director, officers, or staff.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Department of Health. The new NHS: modern, dependable. London: Stationery Office; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health. The NHS plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: Department of Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health. Building a safer NHS for patients. London: Department of Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health. Supporting doctors, protecting patients. London: Department of Health; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selznick P. Focusing organisational research on regulation. In: Noll R, editor. Regulatory policy and the social sciences. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985. pp. 363–368. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breyer S. Regulation and its reform. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogus A. Regulation—legal form and economic theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noll RG. Government regulatory behaviour: a multidisciplinary survey and synthesis. In: Noll RG, editor. Regulatory policy and the social sciences. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985. pp. 9–64. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Majone G. The rise of the regulatory state in Europe. West European Politics. 1994;17(3):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Power M. The audit society: rituals of verification. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancher L, Moran M, editors. Capitalism, culture and regulation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hood C, James O, Jones G, Scott C, Travers T. Regulation inside government: where new public management meets the audit explosion. Public Money and Management. 1998;18(2):61–68. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hood C, Scott C, James O, Jones G, Travers T. Regulation inside government: waste watchers, sleaze busters and the quality police. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferlie E, Pettigrew A, Ashburner L, Fitzgerald L. The new public management in action. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Day P, Klein R. Accountabilities: five public services. London: Tavistock Publications; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ham C. Improving NHS performance: human behaviour and health policy. BMJ. 1999;319:1490–1492. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Day P, Klein R. Inspecting the inspectorates. York: Joseph Rowntree Memorial Trust; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry. Learning from Bristol: the report of the public inquiry into children's heart surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary 1984-1995. London: Stationery Office; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiss AJ. Selecting strategies of social control over organisational life. In: Hawkins K, Thomas JM, editors. Enforcing regulation. Boston: Kluwer-Nijhoff Publishing; 1984. pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kagan RA. The ‘criminology of the corporation’ and regulatory enforcement strategies. In: Hawkins K, Thomas JM, editors. Enforcing regulation. Boston: Kluwer-Nijhoff Publishing; 1984. pp. 67–96. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Day P, Klein R. The regulation of nursing homes: a comparative perspective. Milbank Q. 1987;65:303–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilcox B, Gray J. Inspecting schools: holding schools to account and helping schools to improve. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walshe K. Improvement through inspection? The development of the new commission for health improvement in England and Wales. Qual Health Care. 1999;8:191–196. doi: 10.1136/qshc.8.3.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clough R, editor. Insights into inspection: the regulation of social care. London: Whiting and Birch; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gunningham N, Grabosky P, Sinclair D. Smart regulation: designing environmental policy. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chorafas DN. New regulation of the financial industry. New York: St Martin's Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bardach E, Kagan R. Going by the book: the problem of regulatory unreasonableness. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayres I, Braithwaite J. Responsive regulation: transcending the deregulation debate. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baldwin R, Cave M. Understanding regulation: theory, strategy and practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scrivens E. Accreditation: protecting the professional or the consumer? Buckingham: Open University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brennan TA, Berwick DM. New rules: regulation, markets and the quality of American health care. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Altman SH, Reinhardt UE, Shactman D, editors. Regulating managed care: theory, practice and future options. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 1999. [Google Scholar]