Abstract

Lymphatic failure is a broad term that describes the lymphatic circulation’s inability to adequately transport fluid and solutes out of the interstitium and into the systemic venous circulation, which can result in dysfunction and dysregulation of immune responses, dietary fat absorption, and fluid balance maintenance. Several investigations have recently elucidated the nexus between lymphatic failure and congenital heart disease, and the associated morbidity and mortality is now well-recognized. However, the precise pathophysiology and pathogenesis of lymphatic failure remains poorly understood and relatively understudied, and there are no targeted therapeutics or interventions to reliably prevent its development and progression. Thus, there is growing enthusiasm towards the development and application of novel percutaneous and surgical lymphatic interventions. Moreover, there is consensus that further investigations are needed to delineate the underlying mechanisms of lymphatic failure, which could help identify novel therapeutic targets and develop innovative procedures to improve the overall quality of life and survival of these patients. With these considerations, this review aims to provide an overview of the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature as it relates to current understandings into the pathophysiology and pathogenesis of lymphatic failure in patients with congenital heart disease, while also summarizing strategies for evaluating and managing lymphatic complications, as well as specific areas of interest for future translational and clinical research efforts.

I. Introduction

Lymphatic failure occurs when the lymphatic circulation is unable to adequately transport excess fluid and other contents out of the interstitium and into the systemic venous circulation, which is directly responsible for many of the clinical manifestations and severe complications associated with congenital heart disease (i.e., peripheral edema, pleural effusions, ascites, chylothorax, protein-losing enteropathy, plastic bronchitis, among others) (1–8). Individuals with right-sided or single ventricle defects are especially prone to lymphatic failure because chronically elevated central venous pressures increase lymphatic fluid production and impede lymphatic fluid drainage into the systemic venous circulation, which can lead to progressive overload and congestion of the lymphatic circulation (1,4,8,11).

As a result, there has been growing enthusiasm towards emerging and expanding the applications of novel percutaneous and surgical interventions that may be able to improve lymphatic flow (12–24). However, the exact causes of lymphatic failure remain incompletely understood, and to date, there are no targeted therapeutics that reliably prevent or treat its development and progression (11,25). Thus, there is consensus that focused investigations are needed to elucidate these underlying mechanisms, which could help identify novel therapeutic targets and develop other innovative procedures (26–28).

Therefore, this review aims to provide an overview of the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature with respect to current understandings and existing knowledge gaps in the pathophysiology and pathogenesis of lymphatic failure. In doing so, strategies for evaluating and managing lymphatic failure are summarized alongside their existing limitations, and specific areas of interest for future translational and clinical investigations are highlighted that may help advance this new frontier in congenital heart disease.

II. Overview of the Lymphatic Circulation

The lymphatic system is comprised of a large network of organs, tissues, and vessels that produce, collect, and transport lymphatic fluid, which play an integral role in regulating immune responses, the absorption of dietary fats, and maintaining fluid balance (29–33). Each of these essential functions is facilitated by the lymphatic vasculature, which transports interstitial fluid and other contents (i.e., immune cells, proteins and macromolecules, lipids and chylomicrons, etc.) into and through the lymphatic circulation before returning them to the systemic venous circulation (Figures 1 and 2) (1,30,34). While a critical examination of the complex intricacies that govern fluid exchange between the systemic microcirculation, interstitium, and lymphatic microvasculature is beyond the scope of this review and is detailed elsewhere, it is essential to understand the fundamental principles of interstitial fluid production and its transportation into and through the lymphatic circulation (29,33,35,36).

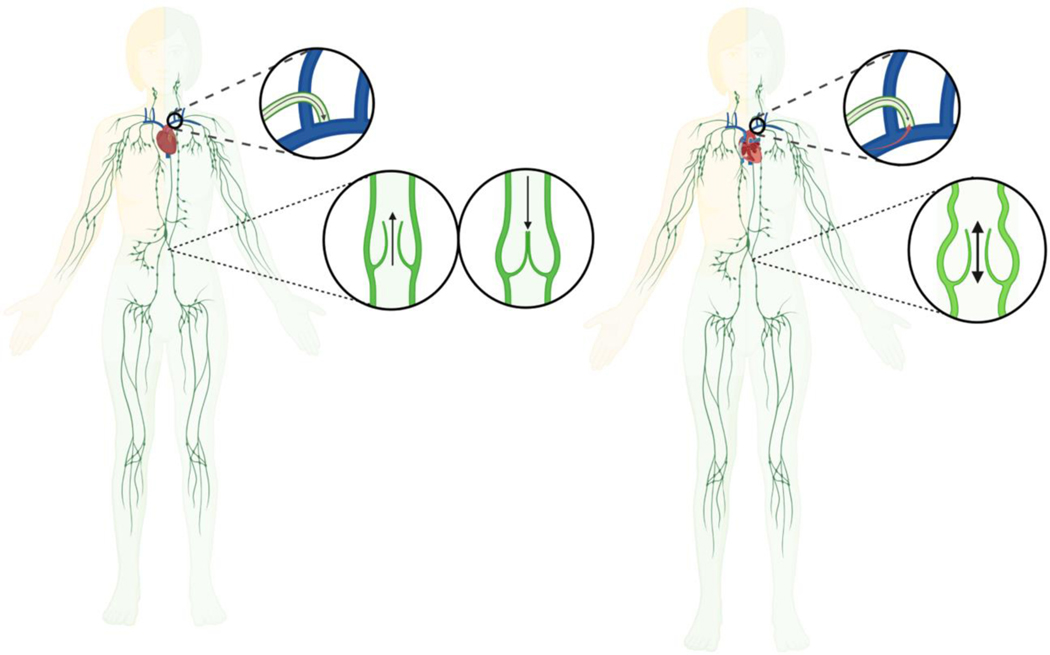

Figure 1:

Overview of the Systemic and Lymphatic Circulation in Biventricular and Single Ventricle Hearts. Unlike the systemic circulation, the lymphatic circulation lacks a central pump. Left: Lymphatic fluid is normally driven from the capillaries to the systemic venous circulation by intrinsic and extrinsic forces. Right: The Fontan procedure provides surgical palliation for single ventricle congenital heart defects by creating a nonphysiological shunt between the systemic venous circulation and the pulmonary artery to bypass the subpulmonic ventricle. As a result, central venous pressures are often chronically and/or obligatorily elevated, which can lead to progressive overload and congestion of the lymphatic circulation that ultimately results in lymphatic failure. Individuals with Fontan circulation may develop dilated and tortuous lymphatic vessels with multiple collaterals and channels, which likely reflect early or failed adaptive responses and pathologic remodeling to reroute abnormal lymphatic fluid flow. Illustration reproduced with permission from Kelly, et al. (34).

Figure 2:

Lymphatic fluid produced by the right side of the head, neck, thorax, and the right upper extremity normally drains into the systemic venous circulation via the right thoracic duct, whereas lymphatic fluid produced by the rest of the body is typically returned through the left lymphatic duct (i.e., thoracic duct), which is the largest lymphatic vessel in the body. Left: Lymphatic fluid normally passes through the thoracic duct before emptying into the systemic venous circulation via an ostial valve near the lymphovenous junction at the confluence between the left subclavian and jugular veins, which helps maintain unidirectional lymphatic fluid flow and prevent blood from regurgitating into the lymphatic circulation. Right: Chronically elevated central venous pressures excessively increase hepatosplanchnic lymphatic fluid production and afterload on the thoracic duct, which impedes lymphatic fluid drainage into the systemic venous circulation. These imbalances in lymphatic fluid overproduction and impaired drainage cause the lymphatic circulation to become overloaded and congested. As a result, lymphatic vessels and valves may become dilated and incompetent, which further impairs unidirectional, antegrade lymphatic fluid flow and exacerbates lymphatic dysfunction and dysregulation. Illustration adapted and modified with permission from Fudim, et al. (1).

A. -. The Systemic Microcirculation, Transvascular Capillary Filtration, and Interstitial Fluid Production

The systemic (blood) circulation utilizes a central pump (i.e., the heart) to generate the high pressures that are necessary to propel blood flow through its closed circuit of arteries, capillaries, and veins (37). As blood passes through the systemic microcirculation, interstitial fluid is produced by transvascular capillary filtration that drives plasma fluid into the interstitium (Figure 3) (2,3,8,10,12,33,34,36,38–45). The rate of transvascular capillary filtration and interstitial fluid production is largely determined by hydrostatic and osmotic pressure differences between the systemic microcirculation and the tissue interstitium (i.e., Starling forces), as well as the permeability of blood capillary endothelial cells (35,36,40,41,46).

Figure 3:

As blood passes through the systemic microcirculation, interstitial fluid is produced by transvascular capillary filtration that drives plasma fluid into the interstitium. Left: Under normal physiologic circumstances, the rate of lymphatic fluid production, transportation, and flow through the lymphatic circulation is autoregulated to maintain a relatively constant volume of interstitial fluid. The removal of interstitial fluid and its contents (i.e., immune cells, proteins and macromolecules, lipids and chylomicrons, etc.) is essential for regulating immune responses, the absorption of dietary fats, and maintaining fluid balance. Right: When lymphatic failure occurs, the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature are unable to adequately transport interstitial fluid and its contents into and through the lymphatic circulation, which may result from pathologic imbalances in homeostatic hydrostatic and osmotic pressures, disruptions in normal capillary permeability and excessive transvascular capillary filtration, as well as impairments in lymphatic reuptake and lymphatic fluid transportation. Progressive overload and congestion of the lymphatic circulation ultimately gets transmitted to smaller and more peripheral lymphatic vessels, which prevents lymphatic capillaries from resorbing fluid and other contents from the interstitium of tissues. Illustration adapted with permission from Rossitto, et al. (9).

While blood capillary permeability is highly variable and may be affected by a multitude of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, there is growing evidence that blood capillary semi-permeability is largely determined by a glycocalyx coating that lines the lumen of endothelium (2,34,35,46–49). The microstructure of the endothelial glycocalyx is tissue- and organ-specific, but is predominately comprised of glycoproteins, proteoglycans, and glycolipids that prevent larger plasma proteins (i.e., albumin) and macromolecules from crossing the endothelium while remaining permeable to water and other small, hydrophobic solutes (33,35,36,48,50,51). In this respect, it is thought that the endothelial glycocalyx establishes the hydrostatic and oncotic gradients between the systemic microcirculation and the interstitium, which in most tissues produces a steady state of net transvascular capillary fluid filtration into the tissue interstitium (36,39–42). As a result, interstitial fluid is predominately comprised of water and typically contains relatively lower concentrations of protein compared to the circulating blood volume, though its composition varies. In any case, interstitial fluid provides essential hydration and nutrients to surrounding tissues (2,34,36,37,49,52). At the same time, interstitial fluid contains small amounts of protein that leak across the blood capillary endothelium, as well as immune cells, dietary fats and fat-soluble vitamins, cellular debris, and other toxic metabolic wastes excreted from cells that must be removed (33,52–54). However, contrary to prior misconceptions, interstitial fluid is not significantly resorbed by the systemic microvasculature. Rather, it is now recognized that the removal of interstitial fluid and its contents is performed almost exclusively by the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature (9,30,36).

B. -. Anatomy and Physiology of the Lymphatic Circulation and its Vasculature

Although the lymphatic circulation complements the systemic circulation and lymphatic vessels share many features in common with blood vessels, the structure and function of the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature are uniquely distinct (Figure 4) (33,55). Unlike the systemic circulation, the lymphatic circulation is a relatively low-pressure, open-ended system that lacks a central pump, and the transportation of interstitial fluid into and through the lymphatic circulation largely depends on intrinsic forces that are uniquely generated by the lymphatic vasculature (Figures 1 and 2) (1,30,33,34,37,45,52). The lymphatic vasculature is organized into lymphatic capillaries (i.e., ‘initial lymphatics’), pre-collector and collector vessels, and larger lymphatic trunks and central collecting ducts that ultimately empty into the systemic venous circulation via a lymphovenous junction near the internal jugular and subclavian veins (Figures 2 and 4) (1,33,35,52,53,55). As detailed below, the structural and functional integrity of the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature are essential for homeostatic fluid balance regulation and the removal of excess interstitial fluid.

Figure 4:

The lymphatic vasculature is organized into lymphatic capillaries, pre-collector and collector vessels, and larger lymphatic trunks and central collecting ducts that ultimately empty into the systemic venous circulation via a lymphovenous junction near the internal jugular and subclavian veins. The structural and functional integrity of the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature are essential for homeostatic fluid balance regulation and the removal of excess interstitial fluid. Lymphatic capillaries are comprised of highly-permeable lymphatic capillary endothelial cells that have a discontinuous or entirely lacking basement membrane, and are joined together by ‘button-like’ intercellular junctions that form overlapping flaps between cell borders. Anchoring filaments prevent the collapse of lymphatic capillaries when interstitial fluid production increases and interstitial pressures rise, which drives interstitial fluid and its contents into the lymphatic microvasculature. Lymphatic fluid is transported into larger lymphatic pre-collector and collector vessels that are comprised of relatively impermeable lymphatic endothelial cells that have a solid, continuous basement membrane, as well as tight, zipper-like intercellular junctions. Precollector and collector vessels are functionally separated by two unidirectional valves, and each individual segment is collectively referred to as a lymphangion, which are surrounded by smooth muscle cells that autonomously. LEC: lymphatic endothelial cell; LMC: lymphatic muscle cell. Illustration reproduced with permission from Brakenhielm, et al. (55).

1. Lymphatic Capillaries and Lymphatic Fluid

Lymphatic capillaries originate in peripheral tissues as blind-ending vessels comprised of highly permeable lymphatic capillary endothelial cells that have a discontinuous or entirely lacking basement membrane and are joined together by ‘button-like’ intercellular junctions that form overlapping flaps between cell borders (Figure 4) (33,55,56). These interendothelial cell junctions predominately regulate the ingress of interstitial fluid, solutes, and cells into lymphatic capillaries, while also preventing fluid and solutes from exiting the lymphatic microcirculation (35). Openings between these junctions are modulated by changes in interstitial pressure that get transmitted to lymphatic capillaries via extracellular anchoring filaments (57). These anchoring filaments and other matrix proteins importantly prevent the collapse of lymphatic capillaries when interstitial fluid production increases and interstitial pressures rise, which largely drives lymphatic capillary filtration and the transportation of interstitial fluid and its contents into the lymphatic microvasculature (35). Once interstitial fluid enters the lymphatic vasculature, it is called lymphatic fluid, then transported into larger lymphatic pre-collector and collector vessels that run alongside arteries and veins (39).

2. Lymphatic Pre-collector and Collector Vessels

Lymphatic pre-collector and collector vessels are comprised of relatively impermeable lymphatic endothelial cells that have a solid, continuous basement membrane, as well as tight, zipper-like intercellular junctions (33,55). Recent work has also identified an endothelial glycocalyx in collecting lymphatics, though its role in normal physiology remains to be determined (58). In any case, pre-collector and collector vessels are functionally separated by two unidirectional valves that are typically bicuspid and prevent retrograde backflow of lymphatic fluid, and each individual segment between two valves is collectively referred to as a lymphangion (Figure 2 and 4) (1,33,55). Larger lymphangions are surrounded by an increasing concentration of specialized smooth muscle cells, which autonomously contract in response to ion channel depolarization (30,45,52,55,59–61). As a result, the lymphatic vasculature generates systolic- and diastolic-like contractions that move phasically from peripheral lymphatic vessels towards to the central lymphatic circulation (30,60,61). The force and frequency of lymphangion contractions is autoregulated and flow-dependent and may be augmented by increases in lymphatic fluid production that elevate pressure or stretching within the lymphatic vasculature, as well as adrenergic stimuli, among other factors (30,33,34,44). These intrinsic contractions are coupled with other extrinsic and passive forces (i.e., skeletal muscle contractions, changes in thoracic pressure during respiration, bowel movements, aortic pulsatility, etc.) that drive lymphatic fluid forward through the lymphatic circulation and into larger lymphatic trunks and central ducts in the thorax before ultimately draining into the systemic venous circulation (Figure 1) (26,35,52,62,63).

3. The Central Lymphatic Circulation and The Thoracic Duct

Lymphatic fluid collected from peripheral tissues and organs is transported into and through the central lymphatic circulation before emptying into the systemic venous circulation via the right and left lymphatic ducts (63,64). The right lymphatic duct typically drains lymphatic fluid produced by the right sides of the head and neck, the right thorax, and the right upper extremity, whereas lymphatic fluid produced by the rest of the body is typically returned to the systemic venous circulation through the left lymphatic duct, which is more commonly referred to as the thoracic duct (Figure 2) (1,30,34).

The thoracic duct is the largest lymphatic vessel in the body and originates just inferior to the aortic hiatus from a dilated lymphatic sack called the cisterna chyli that collects lymphatic fluid from the lower extremities as well as the pelvic and abdominal viscera (65,66). Approximately 25–50% of the lymphatic fluid flowing through the thoracic duct comes from hepatic and splanchnic lymphatics that collect lymphatic fluid from small intestinal lacteals, which are responsible for the resorption and transportation of most dietary lipids and fatty acids (Figure 5) (33,34,67,68). As such, lymphatic fluid within the thoracic duct is often referred to as chyle, which is rich in emulsified fatty acids, cholesterol, and contains relatively higher concentrations of macromolecules and proteins compared to the tissue interstitium.

Figure 5:

Plastic bronchitis and protein-losing enteropathy are among the most devastating complications associated with lymphatic failure. Top: In normal lungs, pulmonary lymphatics drain fluid away from small airways and alveoli, whereas lymphatic vessels in individuals with lymphatic failure are often dilated and have multiple collaterals. Increased transvascular capillary filtration and impaired lymphatic reuptake can cause lymphatic fluid to leak into the pleural cavity and airways, leading to pleural effusions, inflammation, and plastic bronchitis with the production of thick proteinaceous casts. Bottom: Intestinal lymphatics (lacteals) normally transport lipids and fat-soluble nutrients into the lymphatic circulation, while also helping to clear fluid, proteins, and lymphocytes within the interstitium. These functions are critical for nutrient absorption, regulating immune responses, and maintaining homeostasis in the enteric tract. In patients with lymphatic failure, impaired lymphatic drainage can cause retrograde lymphatic fluid flow and protein-losing enteropathy. In patients with protein-losing enteropathy, lacteals are often dilated and engorged, and the intestinal epithelium may become compromised. Failure to collect proteins extravasated into the interstitium and the leakage of interstitial fluid into the lumen of the bowel can result in uncompensated plasma protein loss, lipid depletion, lymphopenia, among other complications. Illustrations adapted and modified with permission from Kelly, et al. and Ozen, et al. (34,68).

It is estimated that approximately 75% of all lymphatic fluid passes through the thoracic duct before emptying into the systemic venous circulation via an ostial valve near the lymphovenous junction at the confluence between the left subclavian and jugular veins (Figure 1) (34,63,69–71). Although it remains debated if any degree of blood regurgitation into the terminal thoracic duct is ever physiologic, lymphatic valves normally prevent retrograde blood flow into the more proximal thoracic duct (70,72–75). In addition, there is evidence that the formation of physiologic thrombi on the thoracic duct ostial valve helps limit the backflow of blood into the lymphatic circulation, and that these thrombi are distinct from those that form due to injury (76–80). The thoracic duct and its outlet valve also have dynamic structural and functional properties like other lymphatic vessels that maintain unidirectional, antegrade lymphatic fluid flow into the systemic venous circulation (43,75). For example, the thoracic duct ostial valve opens synergistically with changes in thoracic duct pressure and central venous pressure to prevent blood from regurgitating into and flowing retrograde through the lymphatic circulation (6,30,61,62,71,72,74,75,81,82). At the same time, pressure differences between the thoracic duct and central venous circulation establish a transvalvular pressure gradient that largely determines the rate of lymphatic fluid drainage into the systemic venous circulation, and thus the overall rate of lymphatic fluid flow through the lymphatic circulation.

4. Autoregulation of Lymphatic Fluid Production, Transportation, and Flow

Under normal physiologic circumstances, the rate of lymphatic fluid production, transportation, and flow through the lymphatic circulation is autoregulated to maintain a relatively constant volume of interstitial fluid (Figure 3) (9,35). In many respects, this is because most factors that increase transvascular capillary filtration and interstitial fluid production (i.e., elevated hydrostatic pressures within blood capillaries, increased blood capillary permeability, etc.) are accompanied by a commensurate increase in interstitial pressure, and therefore lymphatic capillary filtration and lymphatic fluid production. Moreover, increases in lymphatic fluid production often augment lymphatic vessel contractility, which helps accelerate the rate of lymphatic fluid flowing through the lymphatic circulation and into the systemic venous circulation. Together, these and other compensatory mechanisms enable the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature to adequately remove excess interstitial fluid that may be produced across a variety of physiologic circumstances.

For example, while physiologic elevations in systemic blood pressure and intravascular volume may increase perfusion pressure within the systemic microvasculature, and thus the rate of transvascular capillary filtration and interstitial fluid production, this also tends to increase hydrostatic pressures within the interstitium that facilitate fluid transportation into the lymphatic circulation. Additionally, physiologic states of hypertension or hypervolemia are often associated with increases in peripheral vascular resistance that affect capillary blood flow and permeability, as well as the relative concentrations of plasma protein and interstitial solutes that maintain homeostatic hydrostatic and oncotic pressures to preserve a net ingress of interstitial fluid into the lymphatic vasculature. At the same time, related changes in adrenergic tone may augment the force and frequency of lymphatic contractions to increase the rate of lymphatic fluid flow. For similar reasons, although venous hypertension tends to increase hepatosplanchnic lymphatic fluid production and afterload on the thoracic duct, physiologic or transient increases in central venous pressure typically do not prevent lymphatic fluid from adequately draining into the systemic venous circulation due to compensatory responses that help accelerate lymphatic fluid flow and its transportation to the systemic venous circulation (62,67). As a result, the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature play a critical role in regulating fluid balance by helping to maintain homeostatic interstitial oncotic and hydrostatic pressures, replenishing plasma blood volume, and importantly preventing the accumulation of excess interstitial fluid. However, the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature may fail to accomplish these essential functions in pathologic states that result in a sustained increases in blood capillary filtration and/or impaired lymphatic drainage, which may be caused by a variety of factors in patients with congenital heart disease.

III. Etiologies of Lymphatic Failure in Patients with Congenital Heart Disease

The etiologies of lymphatic failure are variable, and both primary (i.e., genetic) and secondary (i.e., acquired) lymphatic disorders have been described in patients with congenital heart disease (83–85). For example, many of the chromosomal abnormalities and mutations associated with congenital heart disease (e.g., Trisomy 21, 22q11.2 deletion, Noonan syndrome) have also been implicated as potential genetic causes of complex lymphatic anomalies (86–89). Furthermore, individuals with congenital heart disease often have lymphatic abnormalities that are similar to those in patients with central conducting lymphatic anomalies, which are a heterogenous group of disorders characterized by dilatation, malformation, dysmotility, and/or obstruction of the major abdominal and/or thoracic lymphatic vessels that impair lymphatic drainage and cause lymphatic fluid to leak into body cavities, resulting in refractory edema, chylothorax, chylous ascites, protein-losing enteropathy, plastic bronchitis, among other complications (13,86,88). Lymphatic complications can also be acquired during or after congenital cardiac surgery if lymphatic vessels are damaged, ligated, or otherwise obstructed either inadvertently or out of necessity (i.e., during challenging dissections or complex cardiac repairs, after decannulation from extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, etc.). However, it is also evident that lymphatic failure may develop in the absence of any identifiable traumatic or anatomic source, which is often attributed to progressive overload and congestion of the lymphatic circulation that results from the chronic hemodynamic and pathophysiologic changes associated with heart failure and congenital heart disease (1,8,34,43,90,91).

Current Insights into the Pathophysiology and Pathogenesis of Lymphatic Failure in Congenital Heart Disease

The precise pathophysiology and pathogenesis of lymphatic failure remains poorly understood, but it is now evident that nearly every aspect of the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature can be affected in patients with non-congenital and congenital heart failure.8 In addition, a growing body of literature has begun to elucidate how, why, and to what degree structural and functional lymphatic abnormalities contribute to progressive clinical deterioration in these patients, and particularly those with failing Fontan circulation.

A. -. The Nexus Between Heart Failure, Failing Fontan Circulation, and Lymphatic Failure

The Fontan procedure provides surgical palliation for single ventricle congenital heart defects by creating a nonphysiological shunt between the systemic venous circulation and the pulmonary artery to bypass the subpulmonic ventricle (Figure 1) (2,26,34,92–97). Although the resulting Fontan circulation is initially compatible with life, most individuals develop low cardiac output syndrome and/or related end-organ dysfunction (i.e., Fontan failure) (92,95,98–102). While the causes and mechanisms of Fontan failure are multifactorial, it is in many ways analogous to the clinical syndrome of heart failure, which is a characterized by systolic and/or diastolic ventricular dysfunction that results in the heart’s inability to adequately circulate blood to meet the demands of the body, or its ability to do so only at elevated filling pressures. Like non-congenital heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, Fontan circulation is characterized by passive venous blood flow through the pulmonary circulation, chronic central venous congestion, and reduced cardiac output (92,95,100–102). Moreover, individuals with Fontan circulation often have preserved systolic function of their systemic single ventricle for several decades, but over time, chronic venous hypertension and/or increases in pulmonary vascular resistance further impede cardiac inflow and exacerbate venous congestion, which ultimately contributes to a progressive, negative spiral of reduced cardiac output that is characteristic of failing Fontan circulation (98,103). Therefore, the earliest clinical manifestations of failing Fontan circulation are often characteristic of heart failure, including poor somatic growth, exercise intolerance, and fluid retention (e.g., peripheral edema, cavitary effusions, etc.) (2,99,101,102). However, it must be underscored that although the clinical manifestations of heart failure and failing Fontan circulation are often attributed to chronic venous hypertension, which is perhaps the most appreciated hemodynamic perturbation observed in patients with Fontan circulation, it is now recognized that many of the symptoms and sequalae of heart failure and other severe Fontan-related complications (i.e., protein-losing enteropathy, plastic bronchitis, etc.) can be more directly attributed to overload, congestion, and failure of the lymphatic circulation (1–8,10,104,105).

B. -. Chronically Elevated Central Venous Pressures and Related Imbalances in Lymphatic Fluid Overproduction and Impaired Lymphatic Drainage

Central venous pressures are often chronically and/or obligatorily elevated in patients with Fontan circulation (12–20 mmHg), increased pulmonary vascular resistance, and reduced cardiac output (99). Importantly, the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature appear to be incapable of adequately compensating for volume overload and congestion beyond a finite range of physiologic central venous pressures, as experimental studies have demonstrated that lymphatic fluid drainage into the systemic venous circulation abruptly declines once central venous pressures exceed 20 mmHg (6,9,26,62,100,106,107). In many respects, this is because chronically elevated central venous pressures excessively increase hepatosplanchnic lymphatic fluid production while at the same time producing a disproportionate increase in thoracic duct afterload that impedes lymphatic fluid drainage into the systemic venous circulation (Figures 1 and 2) (9,108,109). It is also likely that the non-physiologic circulation established by the Fontan procedure alters the fundamental balance of Starling forces that govern fluid and solute transportation between the systemic microcirculation, tissue interstitium, and lymphatic capillaries (Figure 3) (1,2,8,9,43,104). These imbalances in lymphatic fluid overproduction and impaired drainage contribute to chronic overload and congestion of the lymphatic circulation that can ultimately cause lymphatic vessels and valves to become dilated and incompetent, respectively, which further impairs unidirectional, antegrade lymphatic fluid flow and exacerbates lymphatic dysfunction and dysregulation (Figure 2) (8,34,43,75,85,89,109,110).

It is thought that progressive overload and congestion of the lymphatic circulation ultimately gets transmitted to smaller and more peripheral lymphatic vessels, which prevents lymphatic capillaries from resorbing fluid and other contents from the interstitium of tissues (Figure 3) (1,9,10,104). Eventually, the decline in lymphatic uptake and transportation leads to the accumulation of excess interstitial fluid, which is central to the pathogenesis of any form of edema, as well as the development of abnormal lymphatic collaterals or channels that can cause pathologic lymphatic drainage and related complications (e.g., cavitary effusions, hypoalbuminemia, poor nutrient absorption, lymphopenia and impaired immunologic defense, protein-losing enteropathy, plastic bronchitis, etc.; Figure 5) (25,32,34,68,84,111–113).

C. -. Morphologic Abnormalities and Pathologic Remodeling of the Lymphatic Circulation and its Vasculature

While there is some degree of normal variability in the lymphatic vasculature, particularly among individuals with congenital heart disease, it must be noted that high-grade abnormalities are associated with worse clinical outcomes in congenital heart surgery and can now be objectively characterized using established clinical grading systems (65,70,114). However, some individuals may have clinically significant lymphatic abnormalities that are not recognized prior to surgery, while others may develop abnormally dilated and tortuous lymphatic vessels or collateral channels post-operatively, which likely reflect early or failed adaptive responses and pathologic remodeling to reroute abnormal lymphatic fluid flow and compensate for chronic overload and congestion (8,110,115). It is thought that chronic overload and congestion of the lymphatic circulation prevent native systemic and pulmonary lympho-venous connections from adequately decompressing the lymphatic circulation, and that fundamental alterations in the structure and function of the lymphatic microvasculature pathologically reroute lymphatic fluid towards lower-pressure lymphatic beds and likely contribute to severe complications of lymphatic failure like plastic bronchitis and protein-losing enteropathy (Figure 5) (11,25,34,68).

It has been demonstrated that individuals with Fontan circulation and severe complications of lymphatic failure (i.e., protein-losing enteropathy or plastic bronchitis) often have thoracic duct diameters that are up to two times larger than those of healthy subjects and other individuals with Fontan circulation that do not have overt clinical manifestations of lymphatic failure (82). There is also evidence that the cellular architecture of the thoracic duct can still be abnormal in patients with Fontan circulation even when severe complications of lymphatic failure are absent, and that the thoracic duct may be ~10% more elongated compared to healthy subjects (8). The thoracic duct in patients with Fontan circulation may also be surrounded by abnormal smooth muscle cells that are aligned in a loose basket weave-like pattern, rather than the circumferential orientation that is typically observed in others (8,43,60). However, it remains unclear which lymphatic phenotypes may serve as an early prognosticator of lymphatic dysfunction and dysregulation in patients with Fontan circulation, and which are more indicative of advanced disease and impending lymphatic failure. Similarly, some individuals may be anatomically equipped to handle increases in lymphatic flow despite similar degrees of cardiac dysfunction, which likely affects their risk of developing severe complications of lymphatic failure (93). However, it remains to be determined which lymphatic phenotypes may provide some degree of protection against the development of more severe lymphatic complications, and further investigations are needed to determine how and to what degree inherent differences in lymphatic anatomy and physiology effect the incidence and severity of lymphatic complications in patients with congenital heart disease.

D. -. Lymphatic Contractile Dysfunction

It is evident that individuals with heart failure and/or Fontan circulation can have relatively reduced lymphatic pumping pressures and increased lymphatic contraction frequencies, even in the absence of severe complications (8,9,43). For example, recent studies have found that intrinsic pumping capacity of the lymphatic vasculature may be reduced by nearly 20% in patients with Fontan circulation, and lymphangion contraction frequencies may be over twice as fast compared to healthy subjects (43). It has been postulated that the reduced force of lymphatic contractions results from overdistention of the lymphatic vasculature that exceeds their optimal tension-volume and tension-pressure relationships, and that the accelerated contraction frequencies could reflect early, compensatory, physiologic, flowdependent responses to increased lymphatic fluid production and filling pressures within the lymphatic vasculature (8). While these conclusions seem to be supported by earlier findings that individuals with Fontan circulation may have circulating levels of norepinephrine that are 20% higher than healthy subjects, the actual force of lymphangion contractions has not yet been measured in individuals with lymphatic failure, and there have been no quantitative measurements evaluating how tension-volume and tension-pressure relationships effect intrinsic lymphatic contractions in patients with failing Fontan circulation (8,43,61,116). In any case, it is thought that chronic overload and congestion of the lymphatic circulation contribute to long-term functional impairment of lymphatic contractility (1,9,43,117).

E. -. Chronic Inflammation and Microvascular Changes Associated with Lymphatic Failure

Lymphatic failure and the inability to adequately transport interstitial fluid into and through the lymphatic circulation may result from pathologic imbalances in homeostatic hydrostatic and osmotic pressures, disruptions in normal capillary permeability and excessive transvascular capillary filtration, as well as impairments in lymphatic reuptake and lymphatic fluid transportation (Figure 3) (9,35,67). In this respect, systemic venous hypertension not only contributes to lymphatic overload and congestion, but also a chronic state of systemic inflammation that likely contributes to endothelial dysfunction, increased capillary permeability, and excessive interstitial fluid production that can place further demand on the lymphatic circulation and overwhelm its capacity to compensate and adequately regulate fluid balance (52,55,104). As such, some of the earliest manifestations of heart failure can be appreciated within the systemic microcirculation at the subcellular and molecular level (104). For example, chronic inflammation contributes to blood capillary endothelial cell damage that enables excess protein (i.e., albumin) and other macromolecules to extravasate into the interstitium, which can exacerbate the accumulation of excess fluid and other solutes within the interstitium and impair the essential functions of the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature (Figure 3) (1,9,34,43,68,118). Moreover, the endothelial glycocalyx and semi-permeability of blood capillaries is often compromised in patients with heart failure and other etiologies of edema, which could reflect an inability to adequately adapt or compensate to increased interstitial fluid production and/or nonphysiological hydrostatic and oncotic pressure potentials within the tissue interstitium that impair fluid resorption by lymphatic capillaries (48,50). While several studies have demonstrated structural and functional changes within the systemic microcirculation as well as the lymphatic microvasculature in patients with heart failure, others have found that the permeability of the systemic microvasculature may be preserved in some patients with Fontan circulation (8,104). However, further investigations are needed to determine if similar pathophysiologic changes occur within the systemic microcirculation and/or lymphatic microvasculature of patients with severe complications of lymphatic failure.

IV. Evaluation and Management of Lymphatic Failure

The ability to diagnose and treat complications of lymphatic failure has significantly improved in recent years alongside the development and continued evolution of advanced imaging techniques (15–17,23,38,114,119,120). Non-contrast magnetic resonance (MR) lymphangiography is a fast and completely noninvasive imaging modality that is often used to screen for lymphatic disorders in patients requiring congenital heart surgery due to its ability to provide highly detailed images of the lymphatic vasculature, and identify high-grade lymphatic abnormalities associated with worse post-operative outcomes (11,114,120). However, the static images produced by non-contrast MR lymphangiography may be obscured by motion artifact from the heart, lungs, and other structures, which limits their utility in evaluating smaller lymphatic structures (114,121,122). While some of these limitations may be overcome by using contrast, more advanced imaging techniques are required to completely characterize the dynamic structure and function of the lymphatic circulation and its vasculature (121).

In this respect, dynamic contrast-enhanced MR lymphangiography (DCMRL) has in many ways revolutionized the evaluation and management of lymphatic complications in patients with congenital heart disease (113,123–125). DMCRL is a relatively new, highly specialized, and minimally invasive lymphatic imaging technique that utilizes contrast-enhanced time resolved MR angiography sequences to visualize lymphatic fluid flow and perfusion, which can help identify culprit lymphatic lesions that contribute to protein-losing enteropathy, plastic bronchitis, and other complications of lymphatic failure (113,122–126). While it is important to recognize that DCMRL is somewhat more invasive than non-contrast MR lymphangiography because it requires intranodal, intrahepatic, or intramesentaric contrast injections, the minimal risks associated with DCMRL are not prohibitive (11,113,125). Thus, DCMRL has largely become the imaging modality of choice for determining the etiology of lymphatic complications and planning lymphatic interventions in patients with congenital heart disease and other etiologies of lymphatic failure (11,113,121,125,127).

A. Shortcomings of Existing Medical Management Strategies

Until recently, the management of lymphatic failure was largely supportive, and typically centered upon conventional pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic therapies aiming to reduce vascular congestion and lymphatic fluid production (e.g., diuresis, low-fat enteral feeds, etc.), as well as the optimization of goal-directed medical therapies utilized for any patient with heart failure (e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, aldosterone inhibitors, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, etc.) (11,22,25,28,38). Meanwhile, several investigations have sought to determine the potential efficacy of various pharmacotherapies (e.g., steroids, somatostatin analogues, etc.) in mitigating the complications of lymphatic failure, and some studies have demonstrated that dopamine may improve some symptoms of lymphatic failure, and that norepinephrine increases lymphatic contraction frequencies (25,61,68,128,129). However, to date, available medical therapies have had varying degrees of success in preventing or treating lymphatic failure, and the interdependent relationships between these therapeutics and their effects on morbidity, mortality, functional status, and quality of life remain unclear. As such, clinical practice guidelines regarding the use of specific pharmacotherapies to prevent or treat lymphatic failure have not yet been adopted, and there remains substantial variation in how institutions and providers treat this unique population (28,87,129). Thus, there has been growing enthusiasm towards the development and application of novel percutaneous and surgical interventions that may improve the quality of life and overall survival of individuals with lymphatic failure.

B. Established and Emerging Lymphatic Interventions

Percutaneous and surgical interventions used to treat lymphatic complications are generally categorized into two types of approaches, including those that attempt to decompress the lymphatic circulation (i.e., transcatheter thoracic duct dilatation, the innominate vein turn-down procedure, thoracic duct externalization, etc.,), and those that aim to reroute abnormal lymphatic flow by occluding lymphatic ducts or channels (i.e., selective lymphatic embolization, thoracic duct ligation or embolization, pleurodesis, etc.) (12–24). However, it should be noted that although thoracic duct embolization and ligation have long-been used to treat lymphatic complications (e.g., chylothorax, etc.), it is now evident that this approach is often ineffective and can result in persistent, recurrent, or new lymphatic leaks, particularly among individuals with abdominal complications of lymphatic failure (i.e., ascites, protein-losing enteropathy, etc.) (130). Therefore, these interventions should be avoided whenever possible, and they should only be used as a last resort when other treatments options have failed or cannot be performed due to anatomic constraints (11,25).

Meanwhile, it has been repeatedly demonstrated that pathologic lymphatic fluid flow can be effectively occluded and rerouted using selective lymphatic embolization, which can be accomplished using a variety of percutaneous and minimally invasive techniques (13–16). In many ways, selective lymphatic embolization has transformed the treatment of individuals with lymphatic failure, and particularly those with protein-losing enteropathy and plastic bronchitis, yet these interventions are often less effective in patients with lymphatic complications in multiple organ systems or body compartments (i.e., multicompartment lymphatic failure) (15,16,131). Therefore, several interventions have been recently developed that aim to provide more definitive decompression the lymphatic circulation by rerouting lymphatic fluid flow through the thoracic duct into lower pressure environments (13,17,18,20,24,27,119,132–136). Of these, the innominate vein turndown procedure is perhaps the most well-recognized, and early experiences have demonstrated promising results (23,24). However, the innominate vein turndown procedure theoretically increases the risk right-to-left shunting and hypoxemia, which could be avoided with other novel procedures that aim to decompress the lymphatic circulation, including the creation of lymphocutaneous or lymphovenous fistulas (19,22,137). While these procedures may provide effective, short-term symptomatic relief for some individuals, these complex interventions are not always possible, and they are typically reserved as last-resort, salvage therapies for critically ill patients who have failed other conventional therapies. Thus, experiences remain limited, and additional studies are needed to evaluate their overall durability and efficacy.

V. Remaining Knowledge Gaps and Future Investigations

Despite the well-recognized morbidity and mortality associated with lymphatic failure in patients with congenital heart disease, critical knowledge gaps remain in understanding the precise pathophysiology and pathogenesis of lymphatic dysfunction and dysregulation in this unique patient population (1,9,10,27,104). While it is evident that chronically elevated central venous pressures contribute to imbalances in lymphatic fluid overproduction and impaired drainage, additional studies are needed to determine how the development and progression of lymphatic failure is related to inherent and acquired structural or functional lymphatic abnormalities, and how these factors contribute to early and late lymphatic complications. Such insight could have important utility in pre-operative screening for individuals that require congenital cardiac surgery (63,93,114).

Meanwhile, the clinical manifestations of lymphatic failure display significant heterogeneity, and it remains unclear why some individuals develop earlier or more severe complications than others. Therefore, further investigations are needed to elucidate how and why non-congenital and congenital heart failure contribute to the development and progression of lymphatic failure, and to what degree lymphatic overload and congestion itself might exacerbate cardiovascular disease (32). Specifically, little is known about how the lymphatic microvasculature and surrounding cells are affected by lymphatic failure, including the extracellular matrix, interendothelial cell junctions, and endothelial glycocalyces, and additional studies are needed to determine how inherent differences within the lymphatic circulation and its microvasculature may predispose some patients to developing lymphatic failure more quickly than others. While there are likely additional, poorly defined, individual-specific factors that contribute to and protect against the development and progression of lymphatic failure, a comprehensive understanding of the genetic factors involved is lacking, and identifying specific genes and their roles in lymphatic function and failure could provide valuable insight for advanced therapies (68,88). Additionally, the relationship between the lymphatic system and the immune system is complex, and further efforts are needed to determine how lymphatic dysfunction may be exacerbated by chronic states of inflammation, and how immune responses are affected in patients with lymphatic failure.

Although significant improvements have recently been made in lymphatic imaging and interventions, these techniques have limitations, and focused efforts are necessary to develop more advanced, accurate, and accessible imaging methods and treatments (26,27,127). Similarly, translational and clinical investigations are necessary to uncover the precise molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in lymphatic failure, which could provide novel preventative or therapeutic targets. In this respect, clinically relevant animal models will be essential to continue advancing the development and optimization of novel medical and surgical management strategies. For example, it is well-recognized that lymphatic endothelial cells activate platelet receptors and drive hemostasis to maintain separation between lymphatic vessels and in a variety of physiologic conditions, yet it is unclear if these mechanisms increase the risk of thrombus formation after the surgical creation of a lymphovenous anastomosis, and additional studies are warranted to determine optimal post-operative anticoagulation and antiplatelet management strategies (76,80,138–140). However, However, until recently, viable large animal models for studying lymphatic failure were essentially non-existent, and continued efforts to establish representative models that closely mimic human physiology could enhance the translatability of preclinical studies, and help evaluate the safety, efficacy, and long-term durability of novel interventions prior to clinical application (109). Similarly, improved translational research models could help determine if any lymphatic interventions could be performed concomitantly at the time of congenital cardiac surgery to prevent the development and progression of lymphatic failure later in life (132).

VI. Conclusion

Significant advances have been made in evaluating and treating lymphatic failure in patients with congenital heart disease, yet the precise etiology, pathophysiology, and pathogenesis remain poorly understood and relatively understudied. Addressing these critical knowledge gaps will require collaborative, coordinated, and multidisciplinary translational and clinical research efforts. Continued advances in this burgeoning field of congenital heart disease holds promising potential to improve personalized management strategies, and ultimately the quality of life and overall survival of individuals living with congenital heart disease.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Institute for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics of the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number TL1TR001880. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Original illustrations were created with BioRender.com.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fudim M, Salah HM, Sathananthan J, et al. Lymphatic Dysregulation in Patients With Heart Failure: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(1):66–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.04.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.RochéRodríguez M, DiNardo JA. The Lymphatic System in the Fontan Patient-Pathophysiology, Imaging, and Interventions: What the Anesthesiologist Should Know. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2022;36(8 Pt A):2669–2678. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2021.07.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Udink Ten Cate FEA, Tjwa ETTL. Imaging the Lymphatic System in Fontan Patients. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(4):e008972. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.119.008972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kreutzer C, Kreutzer G. The Lymphatic System: The Achilles Heel of the Fontan-Kreutzer Circulation. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2017;8(5):613–623. doi: 10.1177/2150135117720685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kreutzer J, Kreutzer C. Lymphodynamics in Congenital Heart Disease: The Forgotten Circulation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(19):2423–2427. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wegria R, Zekert J, Walter KE, et al. Effect of systemic venous pressure on drainage of lymph from thoracic duct. Am J Physiol. 1963;204:284–288. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1963.204.2.284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels CJ, Bradley EA, Landzberg MJ, et al. Fontan-Associated Liver Disease: Proceedings from the American College of Cardiology Stakeholders Meeting, October 1 to 2, 2015, Washington DC. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(25):3173–3194. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohanakumar S, Telinius N, Kelly B, et al. Morphology and Function of the Lymphatic Vasculature in Patients With a Fontan Circulation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(4):e008074. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.118.008074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossitto G, Mary S, McAllister C, et al. Reduced Lymphatic Reserve in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(24):2817–2829. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itkin M, Rockson SG, Burkhoff D. Pathophysiology of the Lymphatic System in Patients With Heart Failure: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(3):278–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dori Y, Smith CL. Lymphatic Disorders in Patients With Single Ventricle Heart Disease. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:828107. Published 2022 Jun 10. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.828107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itkin M, Pizarro C, Radtke W, Spurrier E, Rabinowitz DA. Lymphatic Management in Single-Ventricle Patients. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2020;23:41–47. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2020.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laje P, Dori Y, Smith C, Pinto E, Taha D, Maeda K. Surgical Management of Central Lymphatic Conduction Disorders: A Review. J Pediatr Surg. 2024;59(2):281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2023.10.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kylat RI, Witte MH, Barber BJ, Dori Y, Ghishan FK. Resolution of Protein-Losing Enteropathy after Congenital Heart Disease Repair by Selective Lymphatic Embolization. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2019;22(6):594–600. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2019.22.6.594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dori Y, Keller MS, Rychik J, Itkin M. Successful treatment of plastic bronchitis by selective lymphatic embolization in a Fontan patient. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):e590–e595. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dori Y, Keller MS, Rome JJ, et al. Percutaneous Lymphatic Embolization of Abnormal Pulmonary Lymphatic Flow as Treatment of Plastic Bronchitis in Patients With Congenital Heart Disease. Circulation. 2016;133(12):1160–1170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith CL, Hoffman TM, Dori Y, Rome JJ. Decompression of the thoracic duct: A novel transcatheter approach. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;95(2):E56–E61. doi: 10.1002/ccd.28446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toyoda Y, Fowler C, Mazzaferro DM, et al. Thoracic Duct Lymphovenous Bypass: A Preliminary Case Series, Surgical Techniques, and Expected Physiologic Outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10(12):e4695. Published 2022 Dec 12. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000004695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reisen B, Kovach SJ, Levin LS, et al. Thoracic duct-to-vein anastomosis for the management of thoracic duct outflow obstruction in newborns and infants: a CASE series. J Pediatr Surg. 2020;55(2):234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weissler JM, Cho EH, Koltz PF, et al. Lymphovenous Anastomosis for the Treatment of Chylothorax in Infants: A Novel Microsurgical Approach to a Devastating Problem [published correction appears in Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 Aug;142(2):581]. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141(6):1502–1507. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindenblatt N, Puippe G, Broglie MA, Giovanoli P, Grünherz L. Lymphovenous Anastomosis for the Treatment of Thoracic Duct Lesion: A Case Report and Systematic Review of Literature. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;84(4):402–408. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laje P, Smood B, Smith C, et al. Surgical creation of lymphocutaneous fistulas for the management of infants with central lymphatic obstruction. Pediatr Surg Int. 2023;39(1):257. Published 2023 Aug 31. doi: 10.1007/s00383-023-05532-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hraska V, Mitchell ME, Woods RK, Hoffman GM, Kindel SJ, Ginde S. Innominate Vein Turn-down Procedure for Failing Fontan Circulation. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2020;23:34–40. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2020.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hraška V Decompression of thoracic duct: new approach for the treatment of failing Fontan. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(2):709–711. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.02.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomasulo CE, Chen JM, Smith CL, Maeda K, Rome JJ, Dori Y. Lymphatic Disorders and Management in Patients With Congenital Heart Disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;113(4):1101–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.10.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reddy S, Handler SS, Wu S, Rabinovitch M, Wright G. Proceedings From the 2019 Stanford Single Ventricle Scientific Summit: Advancing Science for Single Ventricle Patients: From Discovery to Clinical Applications. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(7):e015871. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itkin M, Rockson SG, Witte MH, et al. Research Priorities in Lymphatic Interventions: Recommendations from a Multidisciplinary Research Consensus Panel. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2021;32(5):762.e1–762.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2021.01.269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rychik J, Atz AM, Celermajer DS, et al. Evaluation and Management of the Child and Adult With Fontan Circulation: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;140(6):e234–e284. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ozdowski L, Gupta V. Physiology, Lymphatic System. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; May 1, 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zawieja DC. Contractile physiology of lymphatics. Lymphat Res Biol. 2009;7(2):87–96. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2009.0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aspelund A, Robciuc MR, Karaman S, Makinen T, Alitalo K. Lymphatic System in Cardiovascular Medicine. Circ Res. 2016;118(3):515–530. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Telinius N, Hjortdal VE. Role of the lymphatic vasculature in cardiovascular medicine. Heart. 2019;105(23):1777–1784. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Breslin JW, Yang Y, Scallan JP, Sweat RS, Adderley SP, Murfee WL. Lymphatic Vessel Network Structure and Physiology. Compr Physiol. 2018;9(1):207–299. Published 2018 Dec 13. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c180015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelly B, Mohanakumar S, Hjortdal VE. Diagnosis and Management of Lymphatic Disorders in Congenital Heart Disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22(12):164. Published 2020 Oct 10. doi: 10.1007/s11886-020-01405-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiig H, Swartz MA. Interstitial fluid and lymph formation and transport: physiological regulation and roles in inflammation and cancer. Physiol Rev. 2012;92(3):1005–1060. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levick JR, Michel CC. Microvascular fluid exchange and the revised Starling principle. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87(2):198–210. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore JE Jr, Bertram CD. Lymphatic System Flows. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 2018;50:459–482. doi: 10.1146/annurev-fluid-122316-045259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dori Y, Itkin M. Etiology and new treatment options for patients with plastic bronchitis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152(2):e49–e50. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2016.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansen KC, D'Alessandro A, Clement CC, Santambrogio L. Lymph formation, composition and circulation: a proteomics perspective. Int Immunol. 2015;27(5):219–227. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxv012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michel CC. Starling: the formulation of his hypothesis of microvascular fluid exchange and its significance after 100 years. Exp Physiol. 1997;82(1):1–30. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Starling EH. On the Absorption of Fluids from the Connective Tissue Spaces. J Physiol. 1896;19(4):312–326. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1896.sp000596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levick JR. Capillary filtration-absorption balance reconsidered in light of dynamic extravascular factors [published correction appears in Exp Physiol 1992 Mar;77(2):403]. Exp Physiol. 1991;76(6):825–857. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1991.sp003549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mohanakumar S, Kelly B, Turquetto ALR, et al. Functional lymphatic reserve capacity is depressed in patients with a Fontan circulation. Physiol Rep. 2021;9(11):e14862. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Munn LL. Mechanobiology of lymphatic contractions. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;38:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von der Weid PY, Zawieja DC. Lymphatic smooth muscle: the motor unit of lymph drainage. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(7):1147–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Claesson-Welsh L, Dejana E, McDonald DM. Permeability of the Endothelial Barrier: Identifying and Reconciling Controversies. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(4):314–331. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aldecoa C, Llau JV, Nuvials X, Artigas A. Role of albumin in the preservation of endothelial glycocalyx integrity and the microcirculation: a review. Ann Intensive Care. 2020;10(1):85. Published 2020 Jun 22. doi: 10.1186/s13613-020-00697-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Butler MJ, Down CJ, Foster RR, Satchell SC. The Pathological Relevance of Increased Endothelial Glycocalyx Permeability. Am J Pathol. 2020;190(4):742–751. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore KH, Murphy HA, George EM. The glycocalyx: a central regulator of vascular function. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2021;320(4):R508–R518. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00340.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim YH, Nijst P, Kiefer K, Tang WH. Endothelial Glycocalyx as Biomarker for Cardiovascular Diseases: Mechanistic and Clinical Implications. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2017;14(2):117–126. doi: 10.1007/s11897-017-0320-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pillinger NL, Kam P. Endothelial glycocalyx: basic science and clinical implications. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2017;45(3):295–307. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1704500305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scallan JP, Zawieja SD, Castorena-Gonzalez JA, Davis MJ. Lymphatic pumping: mechanics, mechanisms and malfunction. J Physiol. 2016;594(20):5749–5768. doi: 10.1113/JP272088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scallan J, Huxley VH, Korthuis RJ. Capillary Fluid Exchange: Regulation, Functions, and Pathology. San Rafael (CA): Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Di Stefano R, Erba PA, D’Errico G (2013). The Pathophysiology of Lymphatic Circulation in Different Disease Conditions. In: Mariani G, Manca G, Orsini F, Vidal-Sicart S, Valdés Olmos RA (eds) Atlas of Lymphoscintigraphy and Sentinel Node Mapping. Springer, Milano. 10.1007/978-88-470-2766-4_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brakenhielm E, Alitalo K. Cardiac lymphatics in health and disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16(1):56–68. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0087-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ulvmar MH, Mäkinen T. Heterogeneity in the lymphatic vascular system and its origin. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;111(4):310–321. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leak LV, Burke JF. Ultrastructural studies on the lymphatic anchoring filaments. J Cell Biol. 1968;36(1):129–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gianesini S, Rimondi E, Raffetto JD, et al. Human collecting lymphatic glycocalyx identification by electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):3022. Published 2023 Feb 21. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-30043-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bridenbaugh EA, Gashev AA, Zawieja DC. Lymphatic muscle: a review of contractile function. Lymphat Res Biol. 2003;1(2):147–158. doi: 10.1089/153968503321642633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Briggs Boedtkjer D, Rumessen J, Baandrup U, et al. Identification of interstitial Cajal-like cells in the human thoracic duct. Cells Tissues Organs. 2013;197(2):145–158. doi: 10.1159/000342437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mohanakumar S, Majgaard J, Telinius N, et al. Spontaneous and α-adrenoceptor-induced contractility in human collecting lymphatic vessels require chloride. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;315(2):H389–H401. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00551.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brace RA, Valenzuela GJ. Effects of outflow pressure and vascular volume loading on thoracic duct lymph flow in adult sheep. Am J Physiol. 1990;258(1 Pt 2):R240–R244. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.1.R240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pamarthi V, Pabon-Ramos WM, Marnell V, Hurwitz LM. MRI of the Central Lymphatic System: Indications, Imaging Technique, and Pre-Procedural Planning. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;26(4):175–180. doi: 10.1097/RMR.0000000000000130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ilahi M, St Lucia K, Ilahi TB. Anatomy, Thorax, Thoracic Duct. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; July 24, 2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moazzam S, O'Hagan LA, Clarke AR, et al. The cisterna chyli: a systematic review of definition, prevalence, and anatomy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2022;323(5):H1010–H1018. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00375.2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schipper P, Sukumar M & Mayberry JC. Pertinent Surgical Anatomy of the Thorax and Mediastinum. Current Therapy of Trauma and Surgical Critical Care. Elsevier Inc. 2008;227–251. 10.1016/B978-0-323-04418-9.50037-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tanaka M, Iwakiri Y. The Hepatic Lymphatic Vascular System: Structure, Function, Markers, and Lymphangiogenesis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2(6):733–749. Published 2016 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ozen A, Lenardo MJ. Protein-Losing Enteropathy. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(8):733–748. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2301594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Delaney SW, Shi H, Shokrani A, Sinha UK. Management of Chyle Leak after Head and Neck Surgery: Review of Current Treatment Strategies. Int J Otolaryngol. 2017;2017:8362874. doi: 10.1155/2017/8362874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Phang K, Bowman M, Phillips A, Windsor J. Review of thoracic duct anatomical variations and clinical implications. Clin Anat. 2014;27(4):637–644. doi: 10.1002/ca.22337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu DX, Ma XX, Zhang XM, Wang Q, Li CF. Morphological features and clinical feasibility of thoracic duct: detection with nonenhanced magnetic resonance imaging at 3.0 T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;32(1):94–100. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Seeger M, Bewig B, Günther R, et al. Terminal part of thoracic duct: high-resolution US imaging. Radiology. 2009;252(3):897–904. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2531082036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shimada K, Sato I. Morphological and histological analysis of the thoracic duct at the jugulo-subclavian junction in Japanese cadavers. Clin Anat. 1997;10(3):163–172. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.El Zawahry MD, Sayed NM, El-Awady HM, Abdel-Latif A, El-Gindy M. A study of the gross, microscopic and functional anatomy of the thoracic duct and the lympho-venous junction. Int Surg. 1983;68(2):135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ratnayake CBB, Escott ABJ, Phillips ARJ, Windsor JA. The anatomy and physiology of the terminal thoracic duct and ostial valve in health and disease: potential implications for intervention. J Anat. 2018;233(1):1–14. doi: 10.1111/joa.12811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsukiji N, Suzuki-Inoue K. Impact of Hemostasis on the Lymphatic System in Development and Disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2023;43(10):1747–1754. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.123.318824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hess PR, Rawnsley DR, Jakus Z, et al. Platelets mediate lymphovenous hemostasis to maintain blood-lymphatic separation throughout life. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(1):273–284. doi: 10.1172/JCI70422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Welsh JD, Kahn ML, Sweet DT. Lymphovenous hemostasis and the role of platelets in regulating lymphatic flow and lymphatic vessel maturation. Blood. 2016;128(9):1169–1173. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-04-636415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Janardhan HP, Trivedi CM. Establishment and maintenance of blood-lymph separation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76(10):1865–1876. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03042-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Osada M, Inoue O, Ding G, et al. Platelet activation receptor CLEC-2 regulates blood/lymphatic vessel separation by inhibiting proliferation, migration, and tube formation of lymphatic endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(26):22241–22252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.329987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kelly B, Smith CL, Saravanan M, Dori Y, Hjortdal VE. Spontaneous contractions of the human thoracic duct-Important for securing lymphatic return during positive pressure ventilation?. Physiol Rep. 2022;10(10):e15258. doi: 10.14814/phy2.15258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sung C, Bass JL, Berry JM, Shepard CW, Lindgren B, Kochilas LK. The thoracic duct and the Fontan patient. Echocardiography. 2017;34(9):1347–1352. doi: 10.1111/echo.13639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ramirez-Suarez KI, Tierradentro-García LO, Biko DM, et al. Lymphatic anomalies in congenital heart disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2022;52(10):1862–1876. doi: 10.1007/s00247-022-05449-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pieper CC, Wagenpfeil J, Henkel A, et al. MR lymphangiography of lymphatic abnormalities in children and adults with Noonan syndrome. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):11164. Published 2022 Jul 1. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-13806-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Biko DM, Reisen B, Otero HJ, et al. Imaging of central lymphatic abnormalities in Noonan syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 2019;49(5):586–592. doi: 10.1007/s00247-018-04337-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Trenor CC 3rd, Chaudry G. Complex lymphatic anomalies. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2014;23(4):186–190. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2014.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ricci KW, Iacobas I. How we approach the diagnosis and management of complex lymphatic anomalies. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2022;69 Suppl 3:e28985. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu M, Smith CL, Biko DM, et al. Genetics etiologies and genotype phenotype correlations in a cohort of individuals with central conducting lymphatic anomaly [published correction appears in Eur J Hum Genet. 2022 Jun 3;:]. Eur J Hum Genet. 2022;30(9):1022–1028. doi: 10.1038/s41431-022-01123-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mäkinen T, Boon LM, Vikkula M, Alitalo K. Lymphatic Malformations: Genetics, Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Circ Res. 2021;129(1):136–154. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.121.318142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rijnberg FM, Hazekamp MG, Wentzel JJ, et al. Energetics of Blood Flow in Cardiovascular Disease: Concept and Clinical Implications of Adverse Energetics in Patients With a Fontan Circulation. Circulation. 2018;137(22):2393–2407. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Meadows J, Gauvreau K, Jenkins K. Lymphatic obstruction and protein-losing enteropathy in patients with congenital heart disease. Congenit Heart Dis. 2008;3(4):269–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2008.00201.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Alsaied T, Rathod RH, Aboulhosn JA, et al. Reaching consensus for unified medical language in Fontan care. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8(5):3894–3905. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ghosh RM, Griffis HM, Glatz AC, et al. Prevalence and Cause of Early Fontan Complications: Does the Lymphatic Circulation Play a Role?. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(7):e015318. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.AlZahrani A, Rathod R, Krimly A, Salam Y, AlMarzoog AT, Veldtman GR. The Adult Patient with a Fontan. Cardiol Clin. 2020;38(3):379–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2020.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Book WM, Gerardin J, Saraf A, Marie Valente A, Rodriguez F 3rd. Clinical Phenotypes of Fontan Failure: Implications for Management. Congenit Heart Dis. 2016;11(4):296–308. doi: 10.1111/chd.12368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gewillig M, Brown SC. The Fontan circulation after 45 years: update in physiology. Heart. 2016;102(14):1081–1086. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Fontan F, Baudet E. Surgical repair of tricuspid atresia. Thorax. 1971;26(3):240–248. doi: 10.1136/thx.26.3.240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kirklin JK, Pearce FB, Dabal RJ, Carlo WF Jr, Mauchley DC. Challenges of Cardiac Transplantation Following the Fontan Procedure. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2017;8(4):480–486. doi: 10.1177/2150135117714460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gewillig M, Brown SC, Eyskens B, et al. The Fontan circulation: who controls cardiac output?. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;10(3):428–433. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.218594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rychik J The Relentless Effects of the Fontan Paradox. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2016;19(1):37–43. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Van De Bruaene A, Claessen G, Salaets T, Gewillig M. Late Fontan Circulatory Failure. What Drives Systemic Venous Congestion and Low Cardiac Output in Adult Fontan Patients?. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:825472. Published 2022 Mar 14. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.825472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sallmon H, Ovroutski S, Schleiger A, et al. Late Fontan failure in adult patients is predominantly associated with deteriorating ventricular function. Int J Cardiol. 2021;344:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.09.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gewillig M, Goldberg DJ. Failure of the fontan circulation. Heart Fail Clin. 2014;10(1):105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2013.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cuijpers I, Simmonds SJ, van Bilsen M, et al. Microvascular and lymphatic dysfunction in HFpEF and its associated comorbidities. Basic Res Cardiol. 2020;115(4):39. Published 2020 May 25. doi: 10.1007/s00395-020-0798-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Mertens L, Hagler DJ, Sauer U, Somerville J, Gewillig M. Protein-losing enteropathy after the Fontan operation: an international multicenter study. PLE study group. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;115(5):1063–1073. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(98)70406-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pfeffer MA, Shah AM, Borlaug BA. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction In Perspective. Circ Res. 2019;124(11):1598–1617. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.119.313572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.OĽeary PW. 'Prevalence, clinical presentation and natural history of patients with single ventricle'. Progress in Pediatric Cardiology. 2002;.16(1), 31–38. 10.1016/S1058-9813(02)00042-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kim TH, Yang HK, Jang HJ, Yoo SJ, Khalili K, Kim TK. Abdominal imaging findings in adult patients with Fontan circulation. Insights Imaging. 2018;9(3):357–367. doi: 10.1007/s13244-018-0609-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]