The European Union doesn't usually intend to make health policy but in practice other policies— often to do with the union's origins as a free market—affect health care. Ben Duncan explains how the union and its institutions work and how they can be influenced

European Union law has a profound impact on health service delivery in Britain and other EU countries.1 Yet repeated reassurances to the contrary and attempts to define an EU health policy that does not impinge on national governments' rights to control their healthcare systems have disguised this fact. The result has been that some major changes have taken health ministries and doctors by surprise. A greater willingness to acknowledge the union's role in health care may be expected as it prepares to launch an ambitious new health action programme and member states face up to the consequences of recent European Court of Justice rulings on patients' rights to go abroad for operations.2

This paper gives an overview of current EU policies relevant to medicine and public health and an insight into how these policies are made—and how they can be influenced.

Summary points

European Union law has a major impact on health service provision

Most of this impact comes from laws not specifically designed as health policy interventions

Overt acknowledgement of the union's role in health care may be preferable to its current, rather random, interventions

Information is readily obtainable from online EU information sources, health interest groups, and specialist publications

Health policy can be influenced by judicious lobbying

What is EU health policy?

Official health policy

Official EU health policy has been built on something of a paradox. Union leaders have for years wanted the union to be seen to be “doing something” about issues, like health, that citizens care about. Yet health policy is so high on national political agendas that most governments do not want the union interfering in it. The solution the EU came up with in the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 was to have a mandate of “encouraging cooperation between member states” and “if necessary, lending support to their actions” in public health (article 129(1)). The EU was given the power to spend money on European level health projects but forbidden to pass laws harmonising public health measures in the member states (article 129(4)).

When the EU's powers over health policy were revised in the Amsterdam Treaty of 1997 the mandate was significantly strengthened. The EU was commanded to ensure “a high level of human health protection” in the “definition and implementation of all [union] policies and activities” and to work with member states to improve public health, prevent illness and “obviate sources of danger to human health” (article 152(1)). None the less, harmonisation of member states' public health legislation—with two small exceptions—continued to be prohibited and the EU was mandated to “fully respect” the member states' responsibilities for “the organisation and delivery of health services and medical care” (article 152(4, 5)).

Food safety crises such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy, genetically modified crops, and dioxin in chicken have forced health up the EU agenda in recent years. In 1999 one of the first acts of the incoming president of the European Commission, Romano Prodi, was to create a directorate general for health and consumer protection. Though this gave EU health policy a new profile, most of the directorate's resources are deployed on consumer protection—and in particular food safety. Only around 90 of the staff of 700 work on public health. The EU's role in public health and in health care is likely to grow over coming years (see box B1), but for the moment the official health policy is something of a Cinderella.

Box 1.

EU public health action programme 2002-6

Effect of EU law on health service provision

The European Community Treaty may forbid the union from using its health policy powers in a way that cuts across member states' rights to run their own healthcare systems, but this does not isolate health care, or health professionals, from the effect of EU law in other areas.1,3 Box B2 illustrates the ways in which EU law can affect health policy. Two EU laws that have driven major change in British medicine are worth mentioning: the doctors' directive and the working time directive, neither of which was conceived as a health policy measure.

Box 2.

Types of EU health policy making

The doctors' directive was part of a batch of directives proposed by the European Commission in the 1970s and early 1980s as part of a drive to promote the free movement of workers and professional people. The directive guarantees automatic mutual recognition of most medical qualifications in the EU provided member states implement certain minimum quality guarantees (expressed in terms of the length of training). An individual doctor challenged the fact that NHS consultant posts were not, in fact, open to doctors who had simply completed the minimum training period specified in the directive. Faced with possible legal proceedings the British government's then chief medical officer set up a review of specialist medical training which, in 1993, recommended a move from the prevailing system of a long apprenticeship of “learning by doing” to shorter, more structured postgraduate training.4 The introduction of Calman training, as the new regime was called, has been one of the major events in British medicine in the 1990s. It also has implications for the survival of many smaller hospitals.

The working time directive, passed in 1993, sprung from the commission's social action programme aimed at guaranteeing minimum rights for workers throughout the EU. It established the general principle that no employee could be obliged to work more than 48 hours a week and laid down minimum daily rest periods. It took until April 2000 for governments to agree a deal extending the 48 hour week to junior doctors: it will be phased in from 1 August 2004. Implementing the agreement will mean radical changes in medical staffing rotas in British hospitals—probably involving a move to shift work—as well as a massive expansion in doctor numbers.5 The British government has said it will target its recruitment drive at existing member states that have surplus doctors. However, the NHS expansion will probably make the UK an attractive destination for medical migrants from central and eastern Europe and the developing world.

How is EU health policy made?

Box B2 illustrates the fact that effects on health policy can come from sources other than the European Commission's health directorate. Indeed, sometimes EU influence on health policy can be random and unintentional. It is therefore not possible to talk of a single, linear, policy making process. Nevertheless, several key features can be identified.

Features common to all EU policy making

The institutional triangle—At the heart of all EU policy making lies the interplay between the union's three political institutions: the commission, the parliament, and the council of ministers (see box B3). In theory, the policy making process is simple. The commission proposes laws and policies, and parliament and council then approve the law or policy suitably amended. In reality, the commission does not operate in a political vacuum. Individual commissioners and their officials are regularly obliged to attend parliamentary committees or council of ministers' meetings and explain their actions. The commission requires support from the other two institutions if it wants to launch new laws or initiatives. And the council and parliament jointly control the commission's budget. The commission therefore often finds itself responding to concerns raised in parliament and council: many commission policy or legislative proposals are the result of it responding to an “invitation” from the council or parliament to do something.

Box 3.

The institutional triangle

The European Court of Justice: policy through litigation—The wild card in this process is the European Court of Justice. The court consists of 15 judges (one from each member state). It is the ultimate arbiter on the meaning of the treaty and the laws passed under it. EU law is directly enforceable in the national courts of member states, and these national courts can ask the European court for guidance on its interpretation (article 234). The court takes seriously the treaty obligation to forge an “ever closer union” and interprets EU law in a way that promotes European integration. This means that creative litigation by citizens in front of national courts—as in recent cases on patients' rights to obtain treatment abroad2—can take EU policy in a direction that none of the political institutions either planned or expected.8

Special features of health policy

Agenda setting role of the council presidency—The presidency of the council—the right to chair and set the agenda for council meetings—changes hands every six months. Each member state hosts one health council, usually towards the end of its presidency, and a tradition has developed of the president member state using its six months to highlight an issue close to the heart of their health minister. The council presidency has thus developed a policy initiation role. For example, Finland used its presidency (July-December 1999) to initiate a European debate on promoting mental health. Sweden (January-June 2001) highlighted the problem of alcohol abuse, France (July-December 2000) promoted a debate on nutrition, and Belgium (July-December 2001) launched debates on tackling social inequalities in health and broadening the EU public health competence (www.eu2001.be).

The new European Health Forum—This has been set up by the European Commission to help it formulate health policy. The forum is purely advisory. Its inner core is a programme of invitation only meetings of European representatives of the main “stakeholders” (health non-governmental organisations, healthcare professionals, patient groups, and industry). The first of these meetings took place in November 2001. A second meeting is planned for June 2002. An internet “virtual forum” and an open conference are planned for late 2002, early 2003.

Researching EU policy—and influencing it

The practicalities

The EU policy making process is relatively “transparent” in as much as the dates of meetings and the documents discussed at them are fairly easy to get hold of. The commission and parliament make most of their documents available on the internet, usually within a day of them being published. The court's judgments from 1997 onwards are available on its web site. The council of ministers makes available an online database of its internal documents (http://register.consilium.eu.int/utfregister/frames/introfsEN.htm). Appendix 1 (on bmj.com) includes some online information sources and specialist publications.

The difficulties lie less in getting hold of information, but in being able to understand it and assess its relevance. Texts often assume an understanding of EU procedures and the legal parameters within which they operate. Because power in the EU is spread between 15 national governments and three EU institutions, involving about 120 political parties and even more interest groups, its politics are characterised by multilayered compromises in which everyone gets a little bit of what they were after. A whole lexicon of arcane terminology has been developed by the politicians and diplomats who negotiate these compromises. EU texts are opaque: many universities offer postgraduate courses in understanding them. As in national politics too, the texts do not always tell the whole story. One often needs to be plugged in to the political network to fill in the gaps. Appendix 1 (on bmj.com) gives some tips for successful research, and Appendix 2 (also on bmj.com) gives a more detailed overview of EU policy impact on medicine and health.

Influencing the decision making process

Contrary to popular belief, the EU is very much open to democratic influence. All major EU decisions must be approved by elected politicians. National ministers, sitting in the council, and members of the European parliament (MEPs) sitting in the parliament are sensitive to representations from interest groups and comment in the media. The key to successful lobbying—both at national and EU level—is making your intervention at the right time in the decision making process, having a clear set of demands, and making a convincing political case why they should be accepted. The added complication of lobbying at EU level is that decisions require a high degree of consensus across national and political lines. Success usually requires enlisting the support of one or more EU level networks (see Appendix 1, on bmj.com).

Your local MEP, or an MEP who takes a special interest in the relevant topic, can be a helpful ally in getting an issue raised and asking formal questions to the commission about it. In some instances MEPs may even take up a cause as their own and lobby it for you. Generally, though, influencing policy will require a sustained effort over many months, and possibly years.

Conclusion

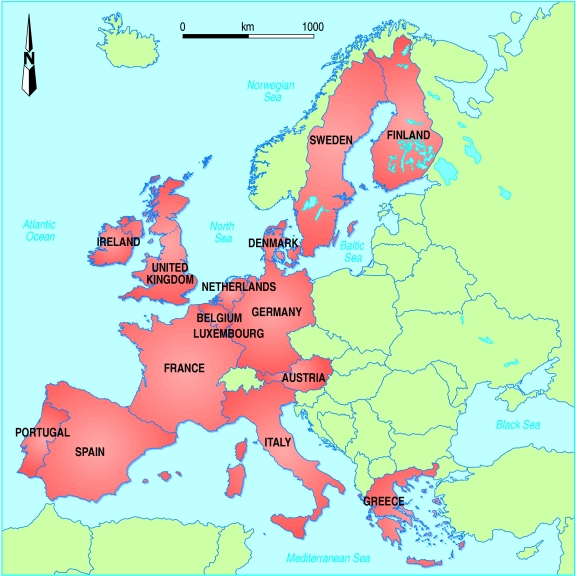

EU laws can and do have a major impact on health service provision, despite the best attempts of national governments to retain control of health care. The result is that, from a medical perspective, EU interventions can seem random and, at times, unhelpful. A solution favoured by some commentators is for the EU to develop an overt healthcare policy.9 While more EU level discussion on healthcare issues seem inevitable as, for example, the new public health programme begins assembling data on treatment outcomes, there is a limit as to how far and how fast the EU can go. The healthcare systems of the existing 15 member states are already very diverse. This will be compounded when the EU expands eastwards. Building consensus on issues to do with health service provision will involve many long and difficult meetings. Important developments can be hoped for as between now and 2004 Europe's politicians review the EU Treaty, but expectations should be kept realistic. Those who want to see major change should go out and lobby for it.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Editorial by Mossialos and McKee

Appendixes with further information on EU policy impacts on health and sources of information appear on bmj.com

References

- 1.Mossialos E, Belcher P. The influence of European law on national health policy. J Eur Social Policy. 1996;6:268–269. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watson R. European court's ruling paves way for cross border treatment. BMJ. 2001;323:128. [Google Scholar]

- 3.European Health Management Association. Impact of European Union internal market regulations on the health services of member states. Dublin: EHMA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Working Group on Specialist Medical Training. Hospital doctors: training for the future. London: Department of Health; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant S. Hours to be main juniors' debate. Hospital Doctor 2001; 7 July.

- 6.Watson R. EU to phase out tobacco advertising despite ruling. BMJ. 2000;321:915. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.See Lang T, Lobstein T, Robertson A, Baumhöfer E. Building a healthy CAP. Eurohealth. 2001;7:34–40. ; Rayner M. European Union policy and health. BMJ 1995;311:1180-1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richards T, Smith R. How should European health policy develop? A discussion. BMJ. 1994;309:116–121. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6947.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mossialos E, McKee M. Is a European healthcare policy emerging? BMJ. 2001;323:248. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.