Abstract

Background

Liver dysfunction contributes to worse clinical outcomes in heart failure (HF) patients. However, studies exploring temporal evolutions of liver function parameters in chronic HF (CHF) patients, and their associations with clinical outcome, are scarce. Detailed temporal patterns of alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP), total bilirubin (TBIL) and albumin (ALB) were investigated, and their relation with clinical outcome, in patients with stable CHF with reduced ejection fraction.

Methods

Tri-monthly plasma samples were collected from 250 patients during 2.2 (1.4–2.5) years of follow-up. ALP, GGTP, ALB, and TBIL were measured in 749 selected samples and the relationship between repeatedly measured biomarker levels and the primary endpoint (PEP; composite of cardiovascular death, heart transplantation, left ventricular assist device implantation, and hospitalization for worsened HF) was evaluated by joint models.

Results

Mean age was 66 ± 13 years; 74% were men, 25% in New York Heart Association class III–IV. 66 (26%) patients reached the PEP. Repeatedly measured levels of TBIL, ALP, GGTP, and ALB were associated with the PEP after adjustment for N-terminal prohormone B-type natriuretic peptide and high sensitivity troponin T (hazard ratio [95% confidence interval] per doubling of biomarker level: 1.98 [1.32; 2.95], p = 0.002; 1.84 [1.09; 3.05], p = 0.018, 1.33 [1.08; 1.63], p = 0.006 and 1.14 [1.09; 1.20], p < 0.001, respectively). Serial levels of ALP and GGTP, and slopes of the temporal evolutions of ALB and TBIL, adjusted for clinical variables, were also significantly associated with the PEP.

Conclusions

Changes in serum levels of TBIL, ALP, GGTP, and ALB precede adverse cardiovascular events in patients with CHF. These routine liver function parameters may provide additional prognostic information in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction patients in clinical practice.

Keywords: heart failure, liver, biomarkers, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, risk assessment

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a systemic disease with poor prognosis, with 5-year mortality rates reaching up to 50% [1]. The importance of liver function for the clinical outcome of patients with HF has been documented both in acute HF [2] and chronic heart failure (CHF) [3–5]. Two phenotypes of liver damage are associated with HF, resulting from congestion and hypoperfusion. Congestion is associated with atrophy, necrosis and fibrosis resulting in increased liver stiffness. In laboratory tests, this is manifested by hyperbilirubinemia with a predominant increase of conjugated bilirubin (direct bilirubin) and slightly elevated alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP) levels, with usually normal or slightly increased concentrations of transaminases. Increases in prothrombin time may be observed, reflecting impairment of proteosynthetic liver function, while hypoalbuminemia may be observed in advanced HF patients as a result of cachexia or enteropathy [6]. Hypoperfusion is associated with ischemic damage of hepatocytes, manifested by elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and total bilirubin [4]. Liver function tests (ALT, AST, total bilirubin) correlate with hemodynamic measurements of cardiac index (CI) and central venous pressure (CVP; ALT, AST, GGTP, alkaline phosphatase [ALP], direct bilirubin, lactate dehydrogenase [LDH]), and their prognostic value is related to their interaction with CI and CVP [4]. Similarly, liver function scoring systems, such as Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) and its modified versions, have found application in prognostication in ambulatory HF patients [7]. The MELD score is calculated according to a formula that includes serum bilirubin and serum creatinine and therefore reflects hepatorenal function and severity of chronic liver disease.

Both hemodynamic phenotypes of liver damage may coexist, especially in the setting of acute HF. Besides hemodynamic insults, metabolic mechanisms contribute to hepatic impairment including inflammatory factors released in both organs as well as the role of the liver as the energy supplier for the heart [8].

These complex cardio-hepatic interactions warrant further investigation, and further insights into the interplay between heart and liver could contribute to improved prognostication in HF patients. Therefore, in the current study, the aim was to evaluate the temporal evolutions of hepatic biomarkers and their associations with adverse clinical outcome, in ambulant patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), and to verify their discriminative ability compared to established biomarkers (N-terminal prohormone B-type natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP], high sensitivity troponin T [hs-TnT]). The design of this study, with frequent repeated biomarker measurements, provides detailed insight into the cardio-hepatic dynamics prior to decompensation. The focus was on the congestive phenotype with impending exacerbation (hemodynamic congestion), and evaluate levels of GGTP, ALP, bilirubin, and, additionally, albumin.

Methods

Study design

The Serial Biomarker Measurements and New Echocardiographic Techniques in Chronic Heart Failure Patients Result in Tailored Prediction of Prognosis (Bio-SHiFT) study is a prospective cohort study of stable patients with CHF, conducted in Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, and Northwest Clinics, Alkmaar, Netherlands, registered in ClinicalTrials. gov (NCT01851538). From October 2011 onwards, consecutive patients were screened. Ambulatory adult patients were included if CHF had been diagnosed according to European Society Guidelines at least 3 months before, and the clinical course was currently stable (i.e. they had not been hospitalized for HF in the prior 3 months). Exact inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Supplemental Figure S1. The study was approved by the responsible medical ethics committees and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All the included patients signed informed consent. Analyses presented in this article comprised 250 HFrEF patients selected out of 263 patients with CHF enrolled during the first inclusion period (October 2011 until June 2013) and were followed-up until November 2015.

Baseline assessment and follow-up procedures

All patients were evaluated by research physicians, who collected information on HF-related symptoms, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, and performed a physical examination. Information on HF etiology, cardiovascular risk factors, medical history and treatment was retrieved from hospital records. History of cardiovascular and other comorbidities was defined as clinical diagnosis thereof, reported in the hospital records. Glomerular filtration rate was estimated with the CKD-EPI equation. Congestion was defined as presence of two or more HF symptoms (dyspnea, orthopnea, fatigue) and/or signs (jugular venous distention, crackles and rales, edema, hepatomegaly and ascites).

Routine outpatient visits were performed by the treating physicians, who were unaware of biomarker results, as measurements took place batch-wise after completion of follow-up. Study follow- up visits were predefined and scheduled every 3 months (± 1 month), in parallel to routine visits at the outpatient clinic. At each study follow-up visit, the research physician performed a short medical evaluation and blood samples were collected. During follow-up, all medication changes and clinical events including occurrence of hospitalization for HF, heart transplantation, left ventricular assist device implantation and mortality, were recorded in the electronic case report forms, and associated discharge letters were collected. Subsequently, a clinical event committee, blinded to the biomarker results, reviewed hospital records and discharge letters and adjudicated the study endpoints. No patients were lost to follow-up.

The primary endpoint (PEP) was a composite of cardiovascular death, heart transplantation, left ventricular assist device implantation, and hospitalization for the management of acute or worsened HF, whichever occurred first. Detailed definitions are described in Text S1 of the Supplementary Material.

Blood sampling

Blood samples were collected at baseline and at each trimonthly study follow-up visit, and were processed and stored at –80°C within 2 hours after collection until batchwise biomarker measurement was performed after completion of follow-up. In the first inclusion round of the Bio-SHiFT study, which was used for the current investigation, a total of 1984 samples were collected before the occurrence of the PEP or censoring in 263 patients (median [IQR] 9 [5–10] blood samples per patient). The focus was on the 250 patients with HFrEF. For reasons of efficiency, for the current investigation, we made a selection of 749 samples in these patients: we selected all baseline samples, and the two samples available closest in time prior to the PEP (which, by design, were 3 months apart) as well as the last two samples available before censoring in patients in whom the PEP did not occur during follow-up. The previous analyses used all available samples in this cohort have demonstrated that the concentration of several plasma and urine biomarkers changes over the months preceding the incident adverse event [9]. By selecting the last 2 samples prior to the incident endpoint, the aim was to capture the changes in biomarkers in patients with incident events. All laboratory personnel were blinded for clinical data and patient outcomes.

Laboratory measurements

Serum bilirubin was measured by a colorimetric Diazo method (lower limit of detection [LLD] 2.5 μmol/L [0.146 mg/dL], Roche/Hitachi cobas c analyzer, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim). Serum ALP was determined by a colorimetric assay (LLD 5 U/L, Roche/Hitachi cobas c analyzer, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim). GGTP was measured by an enzymatic colorimetric assay (LLD 3 U/L, Roche/Hitachi cobas c analyzer). Albumin was quantified by a colorimetric assay (30.4 μmol/L [0.2 g/dL], Roche/Hitachi cobas c analyzer, Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim). All coefficients of variation of these four assays were below 5%. The methods of measurement of NTproBNP, hs- TnT and high sensitivity C-reactive (hs-CRP) are described in Text S3 of the Supplementary Material.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables with a normal distribution are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), whereas the median and interquartile range (IQR) are presented in case of non-normality. Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. In case of non-normal distribution, variables were log2-tranfsormed before entering them in the models. Power calculation and missing data handling are described in Text S3 of the Supplementary Material.

Associations between the repeated measurements of the liver biomarkers and the PEP were evaluated with joint models (JMs). JMs combine a linear mixed effects (LME) model for repeated measurements of a biomarker with a time-to-event relative risk model for the time-to-event data [10]. 1) unadjusted JMs and 2) JMs were used with both the relative risk and LME (the fixed part) models adjusted for: a) age and sex; b) systolic blood pressure, NYHA class I or II vs. III or IV, duration of CHF (years), diabetes mellitus; c) baseline NT-proBNP, baseline hs-TnT. The selection of these four clinical covariates and two biomarkers was based on the observation that those variables differed significantly in patients in whom the endpoint occurred compared to endpoint-free patients (Table 1). Only those variables were selected that differed significantly after a Benjamini-Hochberg procedure with a false discovery rate equal to 0.05. Sampling time was included in both the fixed and random part of the LME models.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (n = 250).

| Variable | Total | PEP | No PEP | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age [years] | 66.2 (12.7) | 68.6 (13.2) | 65.4 (12.4) | 0.042 |

| Male gender | 184 (74%) | 52 (79%) | 132 (72%) | 0.26 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| BMI [kg/m2] | 26.6 (5.7) | 27.1 (5.7) | 26.4 (5.9) | 0.95 |

| Systolic BP [mmHg] | 120 (24) | 113 (23) | 124 (24) | 0.007* |

| Diastolic BP [mmHg] | 72 (18) | 70 (17) | 74 (15) | 0.05 |

| Pulse [beats/min] | 67 (14) | 70 (15) | 66 (12) | 0.26 |

| eGFR [mL/min/1.73 m2] | 58 (34) | 53 (33.2) | 60 (33.9) | 0.24 |

| Features of HF | ||||

| LVEF [%] | 31 ± 9 | 28.5 ± 13 | 32 ± 13 | 0.07 |

| NYHA class I | 75 (30%) | 68 (91%) | 7 (9%) | < 0.001* |

| NYHA class II | 113 (45%) | 83 (73%) | 30 (27%) | < 0.001* |

| NYHA class III or IV | 62 (25%) | 29 (47%) | 33 (53%) | < 0.001* |

| Duration of HF | 4.8 (7.5) | 7.23 (9.55) | 3.77 (6.69) | < 0.001* |

| Ischemic etiology | 116 (46%) | 30 (45%) | 104 (56%) | 0.12 |

| Medical history | ||||

| MI | 95 (38%) | 32 (48%) | 63 (34%) | 0.06 |

| PCI | 81 (32%) | 26 (40%) | 55 (30%) | 0.15 |

| CABG | 42 (17%) | 12 (18%) | 30 (16%) | 0.72 |

| AF | 97 (39%) | 33 (50%) | 64 (35%) | 0.03 |

| Hypertension | 113 (45%) | 34 (51%) | 79 (43%) | 0.23 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 77 (31%) | 29 (44%) | 48 (26%) | 0.007* |

| Known hypercholesterolemia | 94 (38%) | 29 (44%) | 65 (36%) | 0.27 |

| Baseline biomarker concentrations | ||||

| NT-proBNP [pmol/L] | 133 (228) | 297 (343) | 94 (174) | < 0.001* |

| hs-TnT [ng/L] | 17.7 (23.3) | 30.0 (28.1) | 13.8 (18.7) | < 0.001* |

| CRP [mg/L] | 2.20 (4.00) | 2.95 (3.87) | 1.80 (3.47) | 0.02 |

| Albumin [g/L] | 46 (4) | 46 (5) | 64 (4) | 0.68 |

| Bilirubin [μmol/L] | 6 (4) | 7 (5) | 6 (4) | 0.03 |

| ALP [U/L] | 82 (37) | 98 (60) | 79.5 (30) | < 0.001* |

| GGTP [U/L] | 42 (67) | 59 (79) | 38.5 (55.2) | < 0.001* |

| Medication use | ||||

| Beta-blocker | 225 (90%) | 57 (86%) | 168 (91%) | 0.25 |

| ACEI or ARB | 235 (94%) | 59 (89%) | 176 (96%) | 0.06 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 174 (70%) | 50 (76%) | 124 (67%) | 0.20 |

| Diuretic | 227 (91%) | 64 (97%) | 163 (87%) | 0.04 |

| Loop diuretics | 226 (90%) | 64 (97%) | 162 (88%) | 0.03 |

| Thiazides | 6 (2%) | 3 (0.2%) | 3 (0.4%) | 0.18 |

Categorical variables are expressed as count (percentage). Values of continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or as median (interquartile range) in case of skewed distribution.

Significant with new p threshold = 0.007 after Benjamini-Hochberg procedure with false discovery rate (FDR) = 0.05;

ACEI — angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ALP — alkaline phosphatase; ARB — angiotensin II receptor blocker; BMI — body mass index; BP — blood pressure; CABG — coronary artery bypass grafting; CRP — C-reactive protein; eGFR — estimated glomerular filtration rate; GGTP — gamma glutamyl transpeptidase; hs-TnT — high-sensitivity troponin T; KDOQI — Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative; LVEF — left ventricular ejection fraction; MI — myocardial infarction; NT-proBNP — N-terminal prohor-mone of B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA — New York Heart Association; PEP — primary endpoint; PCI — percutaneous coronary intervention

All analyses were performed with R Statistical Software v. 3.4.1. using packages ‘simputation’, ‘nlme’, ‘JMbayes’.

Results

Baseline characteristics and follow-up

Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of the study population. Mean age was 66 ± 13 years; 184 (74%) were men, 62 (25%) were in NYHA class III or IV, and mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 31 ± 9%. During a median (25th–75th percentile) follow-up of 2.2 (1.4–2.5) years, 66 (26%) patients reached the composite PEP; the first event that occurred was rehospitalization for acute or worsened HF in 53 patients, heart transplantation in 3, left ventricular assist device placement in 3, and death from cardiovascular causes occurred in 8 patients. In total, 29 patients died, and among them 24 died from cardiovascular disease.

Baseline liver function

At baseline, 1 (0.4%) patient presented with albumin level below 35 g/L, 1 (1.5%) woman and 6 (3.2%) men presented with increased bilirubin (> 21 μmol/L, p = 0.68). 14 out of 66 (21%) women presented with increased ALP, as did 29 out of 184 (16%) men (defined as > 105 U/L and > 130 U/L, respectively, p = 0.34). 20 (30%) of the women and 73 (39%) of the men presented with increased GGTP (defined as > 40 U/L and > 60 U/L, respectively, p = 0.19). Congestion was found in 157/250 (62.8%) patients and 19 (7,6%) of the patients presented with hepatomegaly at baseline. However, information on hepatomegaly was not available for 34 (13.6%) patients, and hepatomegaly was not assessable in another 54 (21.6%) patients. The presence of congestion was not significantly associated with levels of ALP, GGTP, or bilirubin, but was associated with significantly lower albumin level (median [IQR] 46.00 [43.0; 48.00] vs. 47.0 [45.0; 49.0], p < 0.001). Hepatomegaly and ascites were more frequent in patients with NYHA class III or IV compared to NYHA class I or II (13.7 vs. 7.0%, p < 0.001 and 13.0% vs. 1.7% p < 0.002, respectively). Hepatomegaly was significantly associated with higher ALP (102.0 [77.5; 132.5] vs. 81.00 [65.50; 102.50], p = 0.03) and GGTP level (87.0 [48.0; 174.5] vs. 40.00 [25.5; 75.5], p = 0.003). The presence of ascites was associated with higher bilirubin (11.00 [5.00; 12.50] vs. 6.00 [4.00; 8.00], p = 0.02), and GGTP (112.0 [33.0; 233.5] vs. (42.00 [25.0; 86.0], p = 0.04).

Temporal evolution of hepatic biomarkers

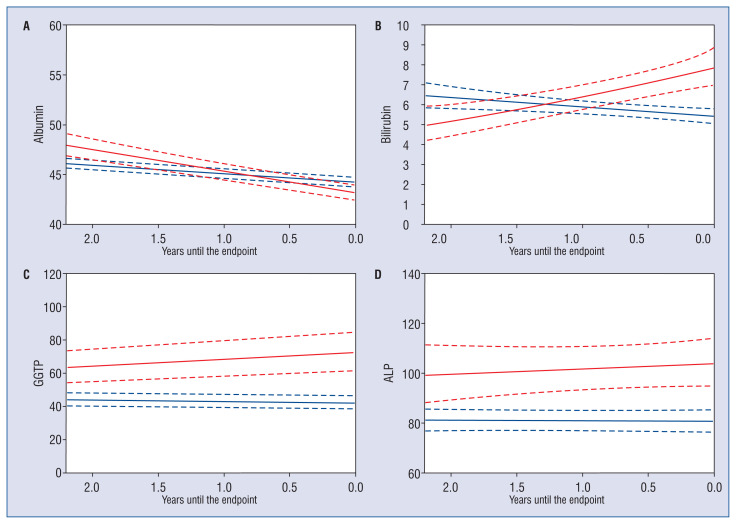

Figure 1 demonstrates the evolution of hepatic biomarkers in relation to the PEP. ALP and GGTP showed significantly different levels in patients with the PEP long before (> 2 years) the PEP occurred, compared to patients who did not experience the PEP throughout the entire follow-up. However, there was little change in their levels, with almost horizontal, slightly diverging average evolutions due to their rise in patients with the PEP as the PEP grew near. Conversely, levels of albumin were higher in those with subsequent PEP, > 2 years before the PEP, and subsequently fell; while bilirubin levels rose less than 1 year before the PEP in those with subsequent PEP.

Figure 1.

Evolution plots of hepatic biomarkers based on the joint models. Average temporal evolution of biomarkers in patients during follow-up. Legend: x–axis — time remaining to the primary endpoint (for patients who experienced adverse events) or time remaining to the last blood sampling (for patients who remained event free). ‘Time zero’ is defined as the occurrence of the primary end point and is presented on the right side of the x-axis, so that the average biomarker trajectory may be visualized as the end point approaches (inherently to this representation, baseline sampling occurred before time zero). Y-axis — biomarker levels expressed in g/L for albumin, μmol/L for bilirubin and U/L for gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP) and alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Solid red line — average temporal pattern of biomarker level in patients who reached the primary end point during follow-up. Solid blue line — average temporal pattern of biomarker level in patients who remained end point free. Betas presented for patients who reached the primary end point (red) and for patients who remained end point free (blue) per one year of follow-up based on linear mixed effects model. Dashed lines — 95% confidence interval.

Predictors of the primary endpoint

Among baseline characteristics analyzed univariably with a Cox model, the following were associated significantly with the PEP: systolic blood pressure, NYHA class I or II vs. III or IV, duration of CHF (years), diabetes mellitus, NT-proBNP, hs- TnT, ALP and GGTP, as presented in Supplementary Table S1 (standard parameters) and Table 2 (hepatic biomarkers).

Table 2.

Baseline and repeated biomarker measurements in relation to clinical outcome.

| Biomarker | Baseline measurement | Repeated measurements | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for age and sex | Adjusted for clinical variables* | Adjusted for biomarkers** | Unadjusted | Adjusted for age and sex | Adjusted for clinical variables * | Adjusted for biomarkers** | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Albumin | 3.25 (0.31; 34.20) | 0.32 | 1.24 (0.10; 15.54) | 0.86 | 1.65 (0.15; 17.92) | 0.68 | 0.47 (0.05; 4.93) | 0.53 | 1.85 (1.18; 2.98) | 0.007 | 1.37 (1.05; 1.80) | 0.014 | 1.001 (0.996; 1.005) | 0.79 | 1.14 (1.09; 1.20) | < 0.001 |

| Bilirubin | 1.41 (1.02; 1.96) | 0.04 | 1.44 (1.01; 2.05) | 0.04 | 1.25 (0.88; 1.78) | 0.21 | 1.12 (0.80; 1.56) | 0.51 | 2.76 (1.94; 3.96) | < 0.001 | 3.47 (2.31; 5.35) | < 0.001 | 1.06 (1.02; 1.11) | 0.004 | 1.98 (1.32; 2.95) | 0.002 |

| ALP | 2.53 (1.69; 3.81) | < 0.001 | 2.40 (1.60; 3.59) | < 0.001 | 2.58 (1.70; 3.94) | < 0.001 | 1.47 (0.98; 2.18) | 0.06 | 3.64 (2.26; 5.55) | < 0.001 | 3.59 (2.23; 6.28) | < 0.001 | 1.13 (1.07; 1.19) | < 0.001 | 1.84 (1.09; 3.05) | 0.018 |

| GGTP | 1.42 (1.17; 1.74) | < 0.001 | 1.43 (1.17; 1.76) | < 0.001 | 1.32 (1.08; 1.62) | 0.007 | 1.21 (1.00; 1.46) | 0.05 | 1.58 (1.29; 1.95) | < 0.001 | 1.60 (1.29; 2.00) | < 0.001 | 1.03 (1.01; 1.06) | 0.001 | 1.33 (1.08; 1.63) | 0.006 |

Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) is given per doubling of bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGTP) level and halving of albumin level; new p value threshold after Bonferroni correction = 0.0125;

covariates include: systolic blood pressure, New York Heart Association class III or IV, duration of chronic heart failure (years), diabetes mellitus;

biomarkers include baseline N-terminal prohormone B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), baseline high sensitivity troponin T (hs-TnT)

The association between hepatic biomarkers and patient outcome is presented in Table 2 (baseline and repeated measurements) and Table 3 (slope and AUC). Baseline ALP and GGTP levels were associated with the PEP, except for models adjusted for established cardiovascular biomarkers (NT-proBNP and hs-TnT), as presented in Table 2. Repeatedly measured levels of bilirubin, ALP and GGTP were associated with the PEP, also after adjustment for age and sex, clinical variables, and NT-proBNP and hs-TnT [hazard ratio, HR [95% confidence intervals, CI] 1.98 [1.32; 2.95], p = 0.002, 1.84 [1.09; 3.05], p = 0.018 and 1.33 [1.08; 1.63], p = 0.006 for biomarker adjusted models, respectively). Albumin showed a significant association in the unadjusted model, after adjustment for age and sex as well as NT-proBNP and hs-TnT, but not when adjusted for clinical variables (HR [95% CI] 1.14 [1.09; 1.20], p < 0.001 for biomarker adjusted models), as presented in Table 2.

Table 3.

Joint models with time-dependent slope and area under the curve.

| Biomarker | Time-dependent slope of the marker’s trajectory | Area under the curve of the marker’s trajectory | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for age and sex | Adjusted for clinical variables* | Adjusted for biomarkers | Unadjusted | Adjusted for age and sex | Adjusted for clinical variables* | Adjusted for biomarkers | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| HR (95 % CI) | P-value | HR (95 % CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Albumin | 2.76 (2.15; 3.61) | < 0.001 | 2.47 (1.90; 2.15) | < 0.001 | 1.61 (1.43; 1.84) | < 0.001 | 1.93 (1.57; 2.47) | < 0.001 | 1.01 (1.09; 0.94) | 0.66 | 1.00 (1.02; 0.99) | 0.35 | 1.02 (1.09; 0.96) | 0.54 | 1.04 (0.89; 1.23) | 0.65 |

| Bilirubin | 1.10 (1.07; 1.14) | < 0.001 | 1.24 (1.15; 1.33) | < 0.001 | 1.72 (1.28; 2.55) | < 0.001 | 1.06 (1.03; 1.10) | < 0.001 | 1.00; (0.990; 1.003) | 0.40 | 1.03 (0.99; 1.06) | 0.10 | 1.01 (0.99; 1.04) | 0.17 | 1.00 (0.97; 1.03) | 0.80 |

| ALP | 1.42 (1.09; 1.91) | 0.009 | 1.22 (0.94; 1.61) | 0.13 | 1.47 (1.11; 2.01) | 0.008 | 1.15 (0.91; 1.51) | 0.24 | 1.00 (0.97; 1.04) | 0.76 | 1.01 (0.97; 1.05) | 0.65 | 1.01 (0.97; 1.05) | 0.61 | 0.99 (0.97; 1.03) | 0.98 |

| GGTP | 0.99 (1.08; 1.18) | 0.048 | 1.09 (0.99; 1.18) | 0.08 | 1.06 (0.95; 1.17) | 0.24 | 1.05 (0.97; 1.14) | 0.19 | 1.018 (1.003; 1.032) | 0.02 | 1.02 (1.00; 1.03) | 0.03 | 1.01 (0.99; 1.03) | 0.07 | 1.01 (0.99; 1.02) | 0.18 |

Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are given per 20% increase of the slope of bilirubin, ALP and GGTP, and 20% decrease of the slope and area under the curve (AUC) of albumin; new P value threshold after Bonferroni correction = 0.0125;

covariates include: systolic blood pressure, NYHA class III or IV, duration of CHF (years), diabetes mellitus;

biomarkers include baseline N-terminal prohormone brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), baseline high sensitivity troponin T (hs-TnT);

ALP — alkaline phosphatase; GGTP — gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase

Models evaluating change, represented by the slope of the temporal evolution, in albumin and bilirubin, both adjusted and unadjusted, showed that both biomarkers were independently associated with the PEP (HR [95% CI] 1.61 [1.43; 1.84], p < 0.001 and 1.72 [1.28; 2.55], p < 0.001 for clinically adjusted models, respectively) (Tab. 3). ALP showed an independent significant association with the PEP in a clinically adjusted model (HR [95% CI] 1.47 [1.11; 2.01], p = 0.008). For none of the biomarkers, the area under the curve of the biomarker trajectory was associated with the PEP (Tab. 3).

Discussion

In this study evaluating serial measurements of hepatic biomarkers in chronic HFrEF patients, observations that bilirubin, ALP and GGTP were independent predictors of clinical outcome in patients without diagnosed liver disease were noted. The levels of ALP and GGTP were higher in patients who experienced the PEP than in event-free patients long before the PE occurred (> 2 years), whereas the levels of bilirubin and albumin changed dynamically with the impending PE and their slope was associated with clinical outcome.

While liver function parameters have previously been examined in relation to clinical outcome of HF patients, previous studies have usually measured hepatic biomarkers at one moment in time only (baseline), and related them to clinical outcome over the years thereafter. With the current investigation this evidence was extended by performing serial assessment of liver function parameters. Such serial measurements, combined with appropriate statistical methods, enabled to properly reconstruct temporal biomarker patterns, and to capture the dynamic aspects of disease as adverse clinical events grow near.

The association of the hepatic biomarkers with clinical outcome may be explained by their link with hemodynamic parameters. Significant associations have previously been observed between central venous pressure and ALP as well as international normalized ratio in patients with acute heart failure. Central venous pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and cardiac index were associated with bilirubin. Moreover, changes in bilirubin correlated positively with changes in central venous pressure over time during decongestion [4, 12]. It has also been observed that liver function improves during treatment of HF with sacubitril/valsartan, more than it does on therapy with enalapril [12]. This is of clinical importance, because preexisting venous congestion increases the risk of acute ischemic hepatitis [13].

Despite the stable, ambulant population included in the study, more than half of patients presented with signs and/or symptoms of congestive heart failure on baseline. A possible explanation is that in some of these patients, medical therapy was not yet fully optimized. Also, in some patients despite optimal treatment, some signs and symptoms of congestion were present due to long-standing CHF. In the present study, the presence of congestion was not significantly associated with levels of ALP, GGTP, or bilirubin. The definition of congestion used in the current study included subjective measures, such as dyspnoea or fatigue. This might have resulted in an overestimation of congestion in some patients, which may have obscured the association with an elevated cholestatic pattern. Although previous studies reported higher levels of ALP, GGTP, and bilirubin in HF, elevation of these markers does not occur in all patients [3]. This aligns with results herein, which support the prognostic value of repeatedly measured cholestatic markers for clinical outcome, regardless of the presence of congestion. Conversely, an association of congestion was found with lower albumin levels. Grodin et al. [14] suggest that patients with lower serum albumin may have more peripheral edema upon presentation, which is one of the components of the definition of congestion and thus may have contributed to this association.

Hepatic congestion associated with elevated central venous pressure may further progress to hepatic fibrosis. In a group of patients with chronic congestive heart failure, higher liver stiffness values were found compared to controls, nearly one-third of the study population had substantial fibrosis, and more than 1 in 7 patients progressed to cirrhosis [15]. Increased liver stiffness correlates positively with bilirubin level according to a study by Taniguchi et al. [16] and is associated with higher HF rehospitalization and mortality rates.

The association between ALP, GGTP and clinical outcome of HFrEF patients, which is independent from NT-proBNP according to the present observations, raises the question on whether one should improve the introduction of hepatoprotective measures and whether this could prevent unfavorable clinical events in this population.

Whereas the association of ALP, GGTP and bilirubin with HF outcome is quite straightforward, the role of albumin has been a subject of debate. Although hypoalbuminemia occurs in 32% of HF patients according to a recent meta-analysis [17], its pathophysiology is not fully understood. Albumin is not cardiac specific, which may be the reason why its repeatedly measured levels were not significantly associated with PE after adjustment for clinical variables. On the other hand, the dynamics of change in its serum level were a strong independent predictor of unfavorable clinical outcome according to the results of the current study. The significance of serum albumin dynamics has been also reported by other researchers both in the acute [2] and chronic [18] HF setting. Ineffective diuresis and fluid overload, as well as increased inflammatory reactions, have been suggested as mechanisms for this link [19]. The prognostic role of albumin has been confirmed also by meta-analysis [17].

Some aspects of this study warrant consideration. First, this cohort consisted mainly of patients with HFrEF patients, and the results can therefore not be extrapolated to CHF patients with preserved LVEF. Second, concomitant measurement of hemodynamic parameters such as central venous pressure or cardiac index could have provided more insight into the mechanisms behind the associations observed, but was not part of the present study protocols.

Conclusions

Changes in serum levels of TBIL, ALP, GGTP, and ALB precede adverse cardiovascular events in patients with CHF. Increased liver parameters are observed even in clinically stable HF patients, for as long as 2 years before adverse events occur. These routine liver function parameters may provide additional prognostic information in HFrEF patients in clinical practice. Further research on early diuretic intervention in patients without overt hemodynamic decompensation, as well as hepatoprotective medication is warranted.

Supplementary Information

Footnotes

Funding: The Bio-SHiFT study was supported by the Jaap Schouten Foundation and Noordwest Akademie.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Gerber Y, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. A contemporary appraisal of the heart failure epidemic in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 2000 to 2010. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(6):996–1004. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biegus J, Hillege HL, Postmus D, et al. Abnormal liver function tests in acute heart failure: relationship with clinical characteristics and outcome in the PROTECT study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(7):830–839. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen LA, Felker GM, Pocock S, et al. Liver function abnormalities and outcome in patients with chronic heart failure: data from the Candesartan in Heart Failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) program. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11(2):170–177. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfn031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Deursen VM, Damman K, Hillege HL, et al. Abnormal liver function in relation to hemodynamic profile in heart failure patients. J Card Fail. 2010;16(1):84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poelzl G, Ess M, Mussner-Seeber C, et al. Liver dysfunction in chronic heart failure: prevalence, characteristics and prognostic significance. Eur J Clin Invest. 2012;42(2):153–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goncalvesova E, Kovacova M. Heart failure affects liver morphology and function. What are the clinical implications? Bratisl Lek Listy. 2018;119(2):98–102. doi: 10.4149/BLL_2018_018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim M, Kato T, Farr M, et al. Hepatic dysfunction in ambulatory patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(22):2253–2261. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correale M, Tarantino N, Petrucci R, et al. Liver disease and heart failure: Back and forth. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;48:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brankovic M, Akkerhuis KM, van Boven N, et al. Patient-specific evolution of renal function in chronic heart failure patients dynamically predicts clinical outcome in the Bio-SHiFT study. Kidney Int. 2018;93(4):952–960. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rizopoulos D. JM: An R package for the joint modelling of longitudinal and time-to-event data. J Statistical Software. 2010;35(9) doi: 10.18637/jss.v035.i09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki K, Claggett B, Minamisawa M, et al. Liver function and prognosis, and influence of sacubitril/valsartan in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2020;22(9):1662–1671. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vishram-Nielsen JKK, Deis T, Balling L, et al. Relationship between invasive hemodynamics and liver function in advanced heart failure. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2019;53(5):235–246. doi: 10.1080/14017431.2019.1646972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuhrmann V, Kneidinger N, Herkner H, et al. Hypoxic hepatitis: underlying conditions and risk factors for mortality in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(8):1397–1405. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1508-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grodin JL, Lala A, Stevens SR, et al. Clinical Implications of Serum Albumin Levels in Acute Heart Failure: Insights From DOSE-AHF and ROSE-AHF. J Card Fail. 2016;22(11):884–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeng M, Chen Yu, Zhao B. Higher liver stiffness in patients with chronic congestive heart failure: data from NHANES with liver ultrasound transient elastography. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(6):6859–6866. doi: 10.21037/apm-21-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taniguchi T, Ohtani T, Kioka H, et al. Liver stiffness reflecting right-sided filling pressure can predict adverse outcomes in patients with heart failure. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(6):955–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Iskandarani M, El Kurdi B, Murtaza G, et al. Prognostic role of albumin level in heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100(10):e24785. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jabbour R, Ling HZ, Norrington K, et al. Serum albumin changes and multivariate dynamic risk modelling in chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176(2):437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterson EJ, Ng TMH, Patel KA, et al. Association of admission vs. nadir serum albumin concentration with short-term treatment outcomes in patients with acute heart failure. J Int Med Res. 2018;46(9):3665–3674. doi: 10.1177/0300060518777349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.