Abstract

BACKGROUND

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) virus has been a world-known pandemic since February 2020. Multiple variances had been established; the most common variants in Israel were omicron and delta.

AIM

To analyze and compare laboratory values in the "omicron" and "delta" variants of the coronavirus by conducting follow-up examinations and laboratory audits on COVID-19 patients admitted to our institution.

METHODS

A retrospective study, two groups, 50 patients in each group. Patients examined positive for COVID-19 were divided into groups according to the common variant at the given time. We reviewed demographic data and laboratory results such as complete blood count and full chemistry, including electrolytes and coagulation parameters.

RESULTS

The mean age was 52%, 66.53 ± 21.7 were female. No significance was found comparing laboratory results in the following disciplines: Blood count, hemoglobin, and lymphocytes (P = 0.41, P = 0.87, P = 0.97). Omicron and delta variants have higher neutrophil counts, though they are not significantly different (P = 0.38). Coagulation tests: Activated paritial thromoplastin test and international normalized ratio (P = 0.72, P = 0.68). We found no significance of abnormality for all electrolytes.

CONCLUSION

The study compares laboratory results of blood tests between two variants of the COVID-19 virus – omicron and delta. We found no significance between the variants. Our results show the need for further research with larger data as well as the need to compare all COVID-19 variants.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Omicron variant, Delta variant

Core Tip: We reviewed lab results of patient positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) during the periods of omicron and delta variants in Israel. retrospective study of patient 18-99 YO excluding pregnant and oncologic patients. The neutrophil index increased above the normal level. There was no difference between the variants in the other count parameters (hemoglobin and white blood cell count) and coagulation functions (activated paritial thromoplastin test, international normalized ratio) and electrolytes (sodium, chloride, phosphorus, and albumin) had no significant variances or deviations from the acceptable norma. hypokalemia was measured in 62% of all COVID-19 patients.

INTRODUCTION

The first case of the coronavirus [(coronavirus disease 2019, COVID-19), severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2)] was announced in December 2019 in Wuhan, China[1,2]. In February 2020, the first coronavirus case was officially detected in Israel[3]. Since its discovery, it has been extensively researched. Furthermore, there is a tendency for variants to mutate over time[4-6].

The virus causes various clinical symptoms, the most common of which are respiratory symptoms, muscle and joint pain, loss of appetite, and loss of smell. The elderly population has shown the highest risk for morbidity and mortality due to COVID-19. Patients over the age of 60 with multiple comorbidities have been shown to be at an incredibly high risk for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, with mortality rates reaching up to 45% in comparison to the young and relatively healthy population -7.8%[7-9]. Although some infected individuals are asymptomatic, they will still carry and spread the virus[10].

At the beginning of 2022, Botswana and South Africa discovered the "omicron" variant (B.1.1.529). It raised concerns due to a large number of mutations in the spike protein, possibly impacting transmissibility and immune response. The delta variant (B.1.617.2) was first identified in India in late 2020 and became a predominant strain globally. It was associated with increased transmissibility compared to earlier variants. Studies suggested an increased risk of hospitalization with the delta variant.

The omicron variant showed some similarity to the "delta" variant for mutations in Q498R and N501Y, strengthening its ability to bind to the ACE2 protein, the most spreadable variant. In addition, the "omicron" has a wide-ranging adhesive ability due to a mutation in H655Y, N679K, and P681H in the cutting/cleavage region of S1-S2 Furin. Moreover, there is evidence of multiple additional mutations of the "omicron" variant[11,12].

Patients who attend the ED (emergency department) can be divided into two groups: the first one with flu-like symptoms and general symptoms, and the second group are patients who had a positive COVID-19 exam at home and then attended the ED. All patients who are admitted to the ED due to COVID-19 symptoms are routinely subjected to various laboratory tests. In many cases, making the appropriate decisions during the initial treatment phase can significantly impact disease progression. Hospitalization of COVID-19 patients is approved in cases where the patient presents with an "in hospital" positive COVID-19 exam and respiratory symptoms.

Today, an antigen test is performed for the initial mapping of patients. However, the question arises: Are there any changes in laboratory data parameters among coronavirus patients who carry the different variants? There is no consistent information on laboratory data in the preliminary phase when a patient is admitted to the ED. Numerous studies have analyzed laboratory results of patients receiving intensive care during hospitalization and general laboratory values for COVID-19 patients, but the difference between various variants has not been examined.

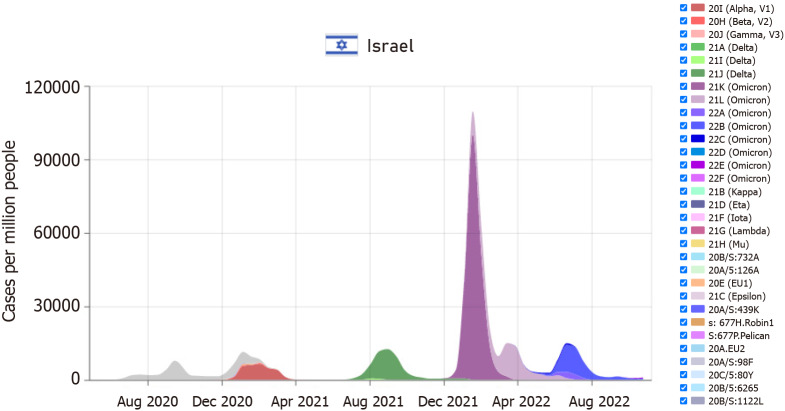

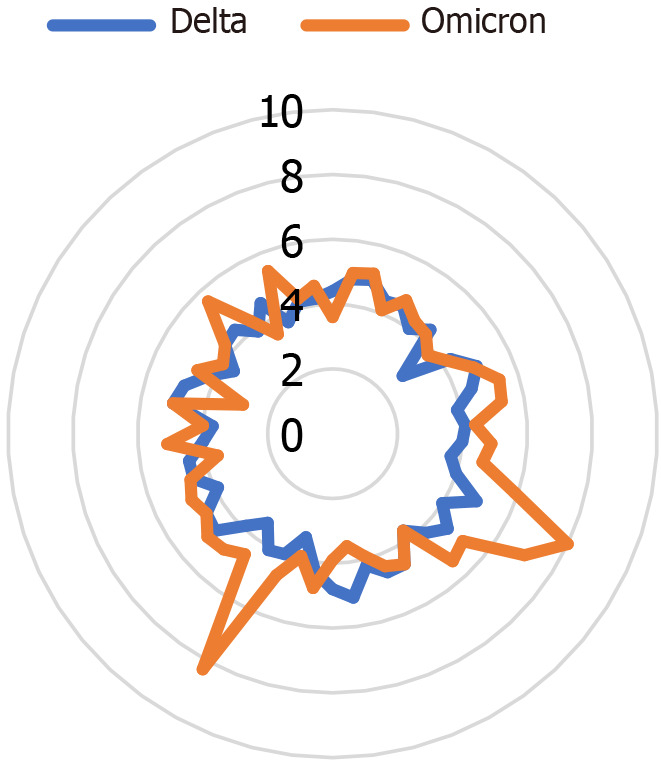

According to the WHO organization, in November 2022, the main variant in Israel was the "omicron," with the first case being observed in November 2021[12-15]. Meanwhile, the first "delta" variant case was discovered in Israel in May 2021. Figure 1 illustrates the month-by-month distribution of the various variants in Israel. It is essential to note that there is a substantial variance between countries worldwide and the presence of a wide range of varieties at any given time[16]. Figure 2 display the Potassium levels of patients with Omicaron and Delta variants.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the corona virus and the different variants by month in Israel[13].

Figure 2.

Scattering graph of laboratory results for potassium. It can be noticed that the majority of the potassium readings during the "delta" variant period are lower than those during the "omicron" variant era.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

At the beginning of 2020, many patients infected with the COVID-19 virus were admitted to our institution. Like all other patients who attend the internal medicine ED, these patients undergo a series of tests for confirmation and assortment of their health status before their hospitalization to the specific internal world or intensive care departments. These exams include a chest X-ray, ECG, and preliminary laboratory tests.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted on patients diagnosed with COVID-19 in our ED. Findings were reported according to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology checklist for retrospective cohort studies, and the local ethics committee approved the study. Data from electronic patient files were retrospectively extracted from the medical records of patients with a diagnosis of the COVID-19 virus who were admitted to the ED of a tertiary medical center in the center region of Israel between August 2021 and April 2022. The range of dates was chosen to include the "delta" period from 08/02/2021 to 11/22/2021 and the "omicron" period from 01/15/2022 to 04/04/2022. Patients included in the study were adults, 18 to 99 years old, who had been hospitalized due to a coronavirus diagnosis—a positive test at admission to the ED, and they have not tested positive for coronavirus in the past, with an exemption for self home exam before attending the hospital. Concurrently, a comprehensive review of dates where the delta and omicron variants exhibited 100% dispersion. The study groups were divided according to the patient's hospitalization dates, corresponding to a specific variant, consisting of 50 patients. Each patient tested positive in at least two "COVID-19" tests that have been done in our hospital. The first positive test was from the ED, and the second was in the internal medicine department upon admission to the department. Additionally, laboratory assessments include blood chemistry, electrolytes, complete blood count, and coagulation blood tests.

Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, young age (under 18), hospitalizations for other diseases/conditions or trauma injuries unrelated to the coronavirus, and underlying diseases that could bias laboratory values and be confounding, such as chronic white blood cell diseases.

The study aims to analyze and compare laboratory values in the "omicron" and "delta" variants of the coronavirus by conducting follow-up examinations and laboratory audits on COVID-19 patients admitted to our institution.

The data was processed using IBM SPSS Statistics software for Windows (version 25.0, Armonk, NY, United States). Charts and curves were drawn using Microsoft Excel 365 (version 2101, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, United States). Continuous measures were assessed for distribution and were presented as mean and standard deviation. Categorical data were presented as prevalence and percentages. Comparisons involving categorical variables were performed using a student's t-test. Furthermore, a multivariate analysis was conducted to examine the clinical and demographic data in relation to various laboratory results.

RESULTS

This study included 100 patients, 50 in the "delta" group and 50 in the "omicron" group. The average age was 66.53 ± 21.7. The majority of the patients were females (52%). No statistically significant differences were identified in age, gender, and comorbidity between the "delta" and the "omicron" variants (P = 0.9, P = 0.23, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic information

|

|

All

|

Delta

|

Omicron

|

P value

|

| Age (SD) | 66.53 (21.7) | 66.23 (23.03) | 66.80 (20.51) | 0.90 |

| Gender-female (%) | 52% | 58% (29) | 46% (23) | 0.23 |

| Mortality (%) | 22% |

Laboratory analysis

No significant differences were found in the index of complete blood count: white count - without leukocytosis, hemoglobin, and lymphocytes, indicators within the normal range (P = 0.97, P = 0.87, P = 0.41 respectively), the neutrophil count was slightly above the norm, but without a statistically significant difference between the variants (P = 0.38). Coagulation functions did not show significant differences in international normalized ratio (INR) and activated paritial thromoplastin test (APTT) parameters (P = 0.72 and P = 0.68, respectively). There were no significant findings for electrolytes in any of the following: sodium, potassium, chloride, phosphorus, and albumin. None of the indicators deviate from the norm. The closest index to significance is quasi-significant potassium P = 0.09 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison between "delta" and "omicron" of laboratory parameters, including complete blood count, blood chemistry, and coagulation factors

|

|

All

|

Delta

|

Omicron

|

P value

|

| WBC (SD) | 9.58 (5.95) | 10.07 (6.57) | 9.09 (5.29) | 0.41 |

| Hb (SD) | 12.64 (2.07) | 12.67 (1.51 | 12.61 (2.52) | 0.87 |

| Neutrophils abs (SD) | 7.91 (5.69) | 8.41(6.31) | 7.41 (5.01) | 0.38 |

| Lymphocytes (SD) | 0.92 (0.66) | 0.92 (0.78) | 0.92 (0.52) | 0.97 |

| PT INR (SD) | 1.04 (0.12) | 1.04 (0.11) | 1.03 (1.13) | 0.68 |

| APTT (SD) | 27.42 (5.15) | 27.24 (4.8) | 27.64 (5.59) | 0.72 |

| Sodium (SD) | 138.19 (5.47) | 138.48 (4.99) | 137.90 (5.96) | 0.60 |

| Potassium (SD) | 4.53 (0.78) | 4.38 (0.69) | 4.68 (1.01) | 0.09 |

| Chloride (SD) | 103.46 (6.13) | 103.60 (4.93) | 103.32 (7.20) | 0.82 |

| Phosphorus (SD) | 3.67 (1.92) | 3.56 (1.38) | 3.86 (2.65) | 0.55 |

| Albumin (SD) | 3.33 (0.60) | 3.29 (0.58) | 3.29 (0.58) | 0.44 |

WBC: White blood cells; Hb: Hemoglobin; PT: Prothrombin time test; INR: International normalized ratio; APTT: Activated paritial thromoplastin test.

DISCUSSION

COVID-19 significantly impacts hospital activity, commencing with a change in the ER and other departments' work structure and the allocation of personnel in all medical and paramedical sectors[17,18]. Today, patients frequently present to our medical Center following a home coronavirus diagnosis and after a new onset of specific symptoms associated with the virus. Over the last two years, many investigations have been conducted to identify and comprehend the virus, prevent its spread, and develop a cure[19].

In Israel, a significant percentage of the population has received multiple vaccine doses, which have been shown to affect the symptoms presented by patients and the severity of the disease's clinical manifestation[20-22]. Nevertheless, we continue to see some ER admissions frequently represented in waves. Over the last two years, the coronavirus has continued to evolve, and new variants were discovered in our districts. Our study examined the most common variants in Israel, "omicron" and "delta". We compared the omicron variant with the delta variant. The two study groups have similar demographic data regarding age, gender, and past illnesses. The following basic laboratory data were compared: complete blood count, coagulation, and blood chemistry. The study by Qin et al[23] (2020) found that lymphopenia is one of the leading indicators of COVID disease, primarily when the disease is defined as severe. This tendency and the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio were also observed in Israel. In our study, there was no significant statistical difference between the two variants and no deviation from the accepted standard[24]. The neutrophil index increased above the normal level in our study, consistent with past research[25]. There was no difference between the variants in the other count parameters (hemoglobin and white blood cell count) and no significant variances or deviations from the acceptable norma. Coagulation functions (APTT, INR) did not differ significantly among the variants. According to the literature, hypokalemia was measured in 62% of all COVID-19 patients infected with the initial variants[26]. In our research, despite this index being the closest to significance among the electrolytes, there was no significant difference between the variants. The other electrolytes (sodium, chloride, phosphorus, and albumin) showed no significance or deviation from the accepted norma.

There are various possible limitations to this study. First, this study only included a single tertiary hospital, which cannot give insight into other medical institutes in our country. The second limitation is the small number of patients who participated in the study; a larger sample group is needed in future studies. Our study did not discover any significant differences in comparing accepted laboratory results during the initial testing phase within the ER setting for the two most recent coronavirus variants in Israel. We could not find a similar comparative study for the "omicron" and "delta" variants in the literature review.

CONCLUSION

While this article provides valuable insights into specific laboratory aspects of delta and omicron variants of COVID-19, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations in failing to compare clinical parameters of the virus variants. Future research endeavors should consider encompassing diverse variants to ensure a more nuanced and systemic approach to addressing the challenges posed by COVID-19.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The article provides a comprehensive overview of the timeline and global impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, emphasizing the emergence of variants such as delta and omicron. Noteworthy symptoms of COVID-19 and the heightened risk among the elderly population are highlighted, including severe acute respiratory distress syndrome risks. The delta variant, identified in India in late 2020, is characterized by increased transmissibility and a higher risk of hospitalization. The omicron variant, first detected in Botswana and South Africa in early 2022, raised concerns due to a significant number of spike protein mutations.

Research motivation

To shed light on the laboratory aspects of COVID-19 patients during the emergence of the delta and omicron variants.

Research objectives

To providing valuable insights into the initial testing phase within the emergency department setting.

Research methods

The study included 100 adult patients, 50 for each variant, with comprehensive laboratory assessments. Rigorous exclusion criteria were applied to ensure the focus on COVID-19-related factors.

Research results

No statistically significant differences were identified in age, gender, and comorbidities between delta and omicron groups. Laboratory analyses, including complete blood count, coagulation, and blood chemistry, revealed no significant variations between the two variants.

Research conclusions

COVID-19 continues to mutate and evolve with different variants emerging, Future research endeavors should consider encompassing diverse variants to ensure a more nuanced and systemic approach to addressing the challenges posed by COVID-19.

Research perspectives

Both omicron and delta variants show high infection rates, similar laboratory results, but clinical evaluation should be conducted to determine the true similarity of those variants.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the "Kaplan Medical Center" Helsinki Committee Institutional Review Board [(Approval No. 0018-22-KMC]).

Informed consent statement: According to the Helsinki Committee decision, our study does not require inform consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: December 12, 2023

First decision: January 15, 2024

Article in press: March 6, 2024

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: Israel

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Oliveira AP, Portugal S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Guo X

Contributor Information

Dana Avraham, Orthopedic Department, Kaplan Medical Center, Rehovot 7661041, Israel. danaav7111@gmail.com.

Amir Herman, Orthopedic Department, Kaplan Medical Center, Rehovot 7661041, Israel.

Gal Shaham, Department of Medicine, Lithuanian University of Health Sciences, Kaunas 44307, Lithuania.

Arkady Shklyar, Emergency Department, Kaplan Medical Center, Rehovot 7661041, Israel.

Elina Sulim, Emergency Department, Kaplan Medical Center, Rehovot 7661041, Israel.

Maria Oulianski, Orthopedic Department, Kaplan Medical Center, Rehovot 7661041, Israel.

Data sharing statement

The authors commit to making the data and materials underlying the findings of this medical article available upon reasonable request. Requests for data should be directed to [Dr. Dana Avraham at Danaav7111@gmail.com. The authors aim to facilitate transparency and reproducibility in scientific research and encourage collaboration within the scientific community. Access to the data will be provided in compliance with ethical standards and institutional regulations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 .

- 2.Li C, Romagnani P, von Brunn A, Anders HJ. SARS-CoV-2 and Europe: timing of containment measures for outbreak control. Infection. 2020;48:483–486. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01420-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. First case in Israel: An Israeli returned from Italy contracted the corona virus. 2020. Available from: https://www.walla.co.il .

- 4.Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R. COVID-19 infection: Origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res. 2020;24:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahase E. Covid-19: WHO declares pandemic because of "alarming levels" of spread, severity, and inaction. BMJ. 2020;368:m1036. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zilberlicht A, Abramov D, Kugelman N, Lavie O, Elias Y, Abramov Y. The Effect of Population Age and Climate on COVID-19 Morbidity and Mortality. Isr Med Assoc J. 2021;23:336–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moal B, Orieux A, Ferté T, Neuraz A, Brat GA, Avillach P, Bonzel CL, Cai T, Cho K, Cossin S, Griffier R, Hanauer DA, Haverkamp C, Ho YL, Hong C, Hutch MR, Klann JG, Le TT, Loh NHW, Luo Y, Makoudjou A, Morris M, Mowery DL, Olson KL, Patel LP, Samayamuthu MJ, Sanz Vidorreta FJ, Schriver ER, Schubert P, Verdy G, Visweswaran S, Wang X, Weber GM, Xia Z, Yuan W, Zhang HG, Zöller D, Kohane IS Consortium for Clinical Characterization of COVID-19 by EHR (4CE), Boyer A, Jouhet V. Acute respiratory distress syndrome after SARS-CoV-2 infection on young adult population: International observational federated study based on electronic health records through the 4CE consortium. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0266985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tzotzos SJ, Fischer B, Fischer H, Zeitlinger M. Incidence of ARDS and outcomes in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: a global literature survey. Crit Care. 2020;24:516. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03240-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shahid Z, Kalayanamitra R, McClafferty B, Kepko D, Ramgobin D, Patel R, Aggarwal CS, Vunnam R, Sahu N, Bhatt D, Jones K, Golamari R, Jain R. COVID-19 and Older Adults: What We Know. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:926–929. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, Horoi M, Le Bon SD, Rodriguez A, Dequanter D, Blecic S, El Afia F, Distinguin L, Chekkoury-Idrissi Y, Hans S, Delgado IL, Calvo-Henriquez C, Lavigne P, Falanga C, Barillari MR, Cammaroto G, Khalife M, Leich P, Souchay C, Rossi C, Journe F, Hsieh J, Edjlali M, Carlier R, Ris L, Lovato A, De Filippis C, Coppee F, Fakhry N, Ayad T, Saussez S. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277:2251–2261. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CoVariants Variant: 21K (Omicron). 2021. Available from: https://covariants.org/variants/21K.Omicron .

- 12. Science Brief: Omicron (B.1.1.529) Variant. 2021 Dec 2. In: CDC COVID-19 Science Briefs [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); 2020– . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Velavan TP, Kuk S, Linh LTK, Lamsfus Calle C, Lalremruata A, Pallerla SR, Kreidenweiss A, Held J, Esen M, Gabor J, Neurohr EM, Shamsrizi P, Fathi A, Biecker E, Berg CP, Ramharter M, Addo MM, Kreuels B, Kremsner PG. Longitudinal monitoring of laboratory markers characterizes hospitalized and ambulatory COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14471. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-93950-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Z, Zhang F, Hu W, Chen Q, Li C, Wu L, Zhang Z, Li B, Ye Q, Mei J, Yue J. Laboratory markers associated with COVID-19 progression in patients with or without comorbidity: A retrospective study. J Clin Lab Anal. 2021;35:e23644. doi: 10.1002/jcla.23644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Israeli Ministry of Health. As of Today, 27/11/2021, One Confirmed Case of the Omicron Variant Was Detected in Israel. 2021. Available from: https://www.gov.il/en/departments/news/27112021-01 .

- 16.CoVariants Estimated Cases by Variant. 2021. Available from: https://covariants.org/cases .

- 17.Bashkin O, Davidovitch N, Asna N, Schwartz D, Dopelt K. The Organizational Atmosphere in Israeli Hospital during COVID-19: Concerns, Perceptions, and Burnout. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colomb-Cotinat M, Poujol I, Monluc S, Vaux S, Olivier C, Le Vu S, Floret N, Golliot F, Berger-Carbonne A GERES study group. Burden of COVID-19 on workers in hospital settings: The French situation during the first wave of the pandemic. Infect Dis Now. 2021;51:560–563. doi: 10.1016/j.idnow.2021.06.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shapiro M, Yavne Y, Shepshelovich D. Predicting Which Patients Are at Risk for Clinical Deterioration in COVID-19: A Review of the Current Models in Use. Isr Med Assoc J. 2022;24:699–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Somekh I, KhudaBukhsh WR, Root ED, Boker LK, Rempala G, Simões EAF, Somekh E. Quantifying the Population-Level Effect of the COVID-19 Mass Vaccination Campaign in Israel: A Modeling Study. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9:ofac087. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gavish N, Yaari R, Huppert A, Katriel G. Population-level implications of the Israeli booster campaign to curtail COVID-19 resurgence. Sci Transl Med. 2022;14:eabn9836. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abn9836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ashkenazi M, Zimlichman E, Zamstein N, Rahav G, Kassif Lerner R, Haviv Y, Pessach IM. A Practical Clinical Score Predicting Respiratory Failure in COVID-19 Patients. Isr Med Assoc J. 2022;24:327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Zhang S, Yang S, Tao Y, Xie C, Ma K, Shang K, Wang W, Tian DS. Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients With Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:762–768. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montiel-Cervantes LA, Medina G, Pilar Cruz-Domínguez M, Pérez-Tapia SM, Jiménez-Martínez MC, Arrieta-Oliva HI, Carballo-Uicab G, López-Pelcastre L, Camacho-Sandoval R. Poor Survival in COVID-19 Associated with Lymphopenia and Higher Neutrophile-Lymphocyte Ratio. Isr Med Assoc J. 2021;23:153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reusch N, De Domenico E, Bonaguro L, Schulte-Schrepping J, Baßler K, Schultze JL, Aschenbrenner AC. Neutrophils in COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2021;12:652470. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.652470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen D, Li X, Song Q, Hu C, Su F, Dai J, Ye Y, Huang J, Zhang X. Assessment of Hypokalemia and Clinical Characteristics in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wenzhou, China. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2011122. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors commit to making the data and materials underlying the findings of this medical article available upon reasonable request. Requests for data should be directed to [Dr. Dana Avraham at Danaav7111@gmail.com. The authors aim to facilitate transparency and reproducibility in scientific research and encourage collaboration within the scientific community. Access to the data will be provided in compliance with ethical standards and institutional regulations.