Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Interest in using holistic review for residency recruitment as a strategy to improve the diversity of the physician workforce has increased. However, no data are published on the prevalence of holistic review in the selection process for family medicine residency programs. We designed this study to assess programs’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes; prevalence; barriers to implementation; and program characteristics associated with the use of holistic review.

Methods:

Data for this study were elicited as part of a 2023 survey conducted by the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance. The nationwide, web-based survey was sent to 739 family medicine residency program directors.

Results:

A total of 309 program directors completed the holistic review portion of the survey. Programs that understood and agreed with holistic review used it more in their selection process. Holistic review was more common in programs with higher rates of residents, faculty, and patients that are underrepresented in medicine. Barriers to holistic review utilization were increased number of applicants, increased resources associated with holistic review, and lack of consensus on the holistic review approach.

Conclusions:

The holistic review process is an area of growing interest to diversify the physician workforce, especially among residencies caring for underresourced communities. Further discussions on the specific scoring rubrics of family medicine residency programs that use holistic review are needed and could help programs that are facing barriers. Widespread use of holistic review to diversify the physician workforce has the potential to improve patient care access and health.

INTRODUCTION

Racial and ethnic diversity in the physician workforce, particularly a higher number of physicians underrepresented in medicine (URiM), improves patient care access and quality of care. 1, 2 URiM is an Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) designation for groups that are underrepresented in medicine compared to their representation in the general US population: Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino/of Spanish origin, Native American/Alaskan Native/Indigenous, and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islanders. 3 URiM physicians are more likely to practice in primary care and work in underresourced communities. 4, 5Racial concordance between patients and physicians also contributes to a more effective therapeutic relationship, improved patient satisfaction, and improved patient outcomes. 2, 6, 7

Unfortunately, this underrepresentation has been found among American Board of Family Medicine certification candidates as recently as the years 2010 to 2020, with the percentage of Black/African American individuals at 8.1% compared to 12.8% of the US population and the percentage of Hispanic/Latino/of Spanish origin individuals at 9.3% compared to 18.4%. 8, 9 The medical residency selection process generally is divided into three primary stages: initial screening of applicants for interviews, interviewing applicants, and ranking applicants. Historically, residency programs have used academic metrics such as United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) scores when evaluating applicants and often screen out applicants based on those scores early in the process. 10 However, previous research has shown that USMLE Step 1 and 2 scores do not correlate with acquisition of clinical skills 11 and may limit recruitment of a diverse physician workforce, because URiM and students who identify as women historically have performed lower than White male counterparts on standardized exams and are therefore negatively impacted by such an evaluation system. 12

To improve the diversity of the physician workforce, AAMC has long championed holistic review in the admissions process at the level of undergraduate medical education. 13 Holistic review is defined as

mission-aligned admissions or selection processes that take into consideration applicants’ experiences, attributes, and academic metrics as well as the value an applicant would contribute to learning, practice, and teaching. It allows admissions committees to consider the “whole” applicant, rather than disproportionately focusing on any one factor.

AAMC 14

In practice, a program instituting holistic review determines for itself a rubric, including applicants’ experiences, attributes, and academic metrics, necessary to achieve its specific mission. Programs may look into not only traditional measures of diversity such as race, ethnicity, and gender, but also factors like socioeconomic status, language capabilities, rural representation, and distance traveled 15 (ie, how far a student has come in light of discrimination or a lack of resources or support) to determine how equipped an applicant might be to meet the needs of diverse patient populations. Since the introduction of holistic review, undergraduate medical education admissions have been successful in having more diverse interview pools than when using academic metrics alone. 16

Implementation of holistic review at the graduate medical education level has the potential to improve the diversity of the physician workforce. However, in the aftermath of the Supreme Court decision Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v President and Fellows of Harvard College 17 to end affirmative action in college admissions, many residency programs are seeking methods to assess an applicant’s diverse lived experiences. At a large academic center trying to achieve improved racial concordance, using a systematic holistic application review process significantly increased the proportion of interviewed and matched candidates who identified as URiM. 18

Currently, no data has been published on the prevalence of holistic review in the family medicine residency program (FMRP) selection process. Additionally, while FMRPs may take into consideration components outside of academic metrics, whether each component of the experiences, attributes, and academic metrics framework is weighed equally or whether programs still filter out candidates based solely on academic metrics is unclear. To explore the current scope of holistic review within FMRPs, this study developed a series of questions that were included in the 2023 family medicine residency program directors’ survey sent by the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA). Survey objectives were to determine: (a) knowledge, skills, and attitudes of holistic review; (b) current prevalence and intensity of formal holistic review in FMRPs; (c) barriers to implementation of holistic review as experienced by FMRPs; and (d) program characteristics’ correlations with the presence of holistic review.

METHODS

Measures

The survey questions were part of a larger omnibus survey conducted by CERA. The larger survey included items assessing demographic and program characteristics that were available to all study teams contributing survey items. Program characteristics and program director (PD) demographic variables used in the study included measures of program type, size of the service community, number of residents, years as a PD, and PD self-identification as URiM. We mapped existing omnibus categories of service community size to Health Resources and Services Administration definitions of rurality by creating a variable for rural as communities of less than 30,000 and urban as greater than or equal to 30,000. 19

The study team developed 10 items that were added to the omnibus survey related to holistic review and additional program characteristics. Survey questions resulted from a literature review. For this survey, we used the AAMC definition of holistic review, shared earlier; that definition was provided to respondents to provide a uniform understanding prior to answering the developed items. Table 1 describes the items developed for the survey.

Table 1. Survey Items.

|

Concept |

Item |

Response options |

|

Agreement |

How much do you agree with using a holistic approach to recruiting applicants? |

• Strongly disagree • Disagree • Neutral • Agree • Strongly agree |

|

Understanding |

To what extent do you understand a holistic approach for applicant review? |

• Not at all • To some extent • To a large extent • Completely |

|

Screening |

To what extent does your program utilize holistic review in the initial screening of applicants to interview? |

|

|

Interviewing |

To what extent does your program utilize holistic review interviewing applicants? |

|

|

Ranking |

To what extent does your program utilize holistic review ranking applicants? |

|

|

Barriers |

What is the biggest barrier to implementing a holistic review framework for your program? . . . . . . . . . |

• Our program is primarily ranked based on the performance metrics of applicants/matched residents. • Concerns that holistic review is not the right approach • Difficulty reaching consensus in defining what a holistic approach would be • Lack of experience implementing a holistic review • Increased resources required to implement a holistic review • Increasing number of applicants • Other • None of the above |

|

What is the second biggest barrier to implementing a holistic review framework for your program? . | ||

|

Demographics |

Please estimate to the best of your ability the percentage of current residents in your program that are URiM.* |

• 0% • 1%–10% • 11%–25% • 26%–50% • >50% |

|

Please estimate to the best of your ability the percentage of URiM* patients that are served by residents. | ||

|

Please estimate to the best of your ability the percentage of current faculty members in your residency program that are URiM.* |

*URiM as defined by the Association of American Medical Colleges (Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino/of Spanish origin, Native American/Alaskan Native/Indigenous, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islanders)

Abbreviation: URiM: underrepresented in medicine

The CERA Steering Committee evaluated questions for consistency with the overall subproject aim, readability, and existing evidence of reliability and validity. Pretesting was done on family medicine educators who were not part of the target population. Questions were modified for flow, timing, and readability. The project was approved by the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) Institutional Review Board. Data were collected between April and May of 2023.

The survey was sent to all 745 US family medicine residency PDs as identified by the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. Email invitations to participate were delivered with the survey, available through the online program SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey, Inc). Three follow-up emails to encourage nonrespondents to participate were sent weekly after the initial email invitation, and a fourth reminder was sent 1 day before the survey closed. Six email addresses were undeliverable, leaving 739 invitations delivered. The survey contained a qualifying question to remove programs that had not had three resident classes. Forty-eight program directors indicated that they did not meet the criteria; these responses were removed from the sample, reducing the sample size to 691.

Analyses

We used frequencies for univariate descriptions. We did bivariate comparisons using ꭓ2 comparisons for categorical variables. We performed Kendall τb correlations for ordinal variables to account for smaller datasets and the presence of ties among the data. 20, 21 We used a level of significance of P<.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata 17 (StataCorp LLC).

RESULTS

The overall response rate for the survey was 44.72% (309/691). Most of the FMRPs were community-based and university-affiliated (58.8%), 24.1% were community-based only, and 16.2% were university-based. Only 11% of FMRPs were considered rural, serving a community size of less than 30,000. The rest of the FMRPs were more urban, with 20.3% of them serving a community size of 75,000 to 149,999, 25.1% serving a community size of 150,000 to 499,999, and 17.2% serving a population greater than 1,000,000. In terms of the number of residents within FMRPs, 40.2% of them had less than 19 residents, 44.3% had 19 to 31 residents, and 15.1% had more than 31 residents. The distribution in the duration of years that PDs had been in their role was approximately even: 26.8% were PDs for less than 3 years, 28.2% for 3 to 5 years, 18.6% for 6 to 9 years, and 26.1% for at least 10 years. Only 18.9% of the PDs reported their own status as URiM.

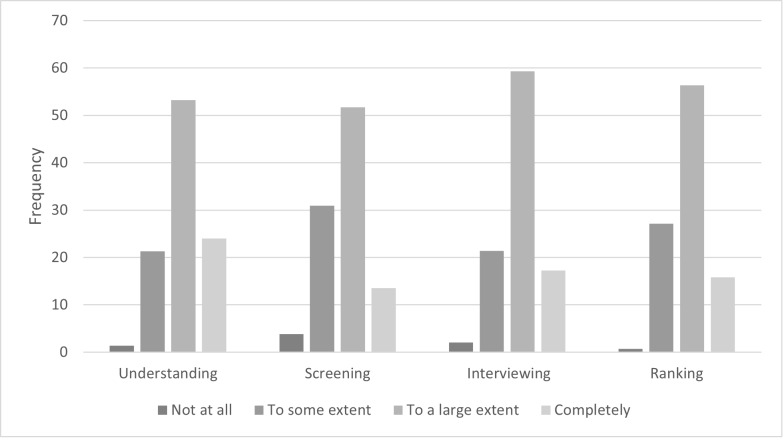

In terms of knowledge, skills, and attitudes, 75% of FMRPs agreed/strongly agreed (38% agreed; 37% strongly agreed) with the use of a holistic review approach for their selection process. Also, 72% of FMRPs self-reported understanding holistic review, with 50% self-reporting understanding to a large extent and 22% self-reporting understanding it completely. The majority of FMRPs also reported using holistic review to a large extent in all of the selection process stages: screening, interviewing, and ranking (Figure 1).

Figure 1 . Extent of Understanding and Use of Holistic Review.

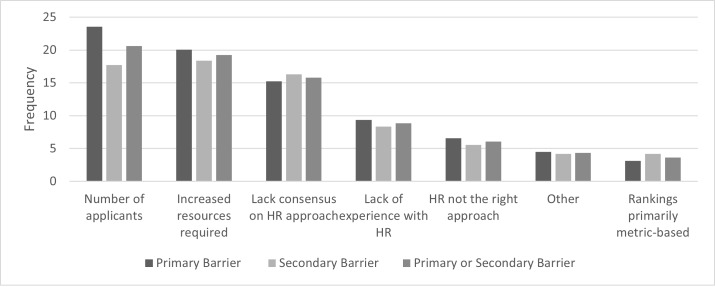

The top three barriers to implementing a holistic review framework were the number of applicants, the increased resources associated with it, and lack of consensus within programs on the holistic review approach (Figure 2).

Figure 2 . Barriers to Implementing a Holistic Review Framework.

We found a significant negative correlation between the length of time served as PD and agreeing with holistic review as a selection process (Table 2). Similarly, we noted significant negative correlations between the length of time served as PD and use of holistic review in the screening, interviewing, and ranking stages of the selection process. In contrast, we identified significant positive correlations with aspects of holistic review with larger numbers of residents (ie, screening); higher rates of URiM residents (ie, interviewing); higher rates of URiM faculty (ie, self-reported understanding, agreement, screening, interviewing, and ranking); higher rates of URiM patients (ie, agreement, interviewing, and ranking); and larger community sizes (ie, agreement). We also found consistently significant positive correlations between FMRPs’ agreement and self-reported understanding and implementation of holistic review throughout the three stages of the selection process (Table 3).

Table 2. Correlations With Program Director and Program Characteristics and Aspects of Holistic Review.

|

Characteristics |

Understanding Kendall τb ( P value) |

Agreement Kendall τb ( P value) |

Screening Kendall τb ( P value) |

Interviewing Kendall τb ( P value) |

Ranking Kendall τb ( P value) |

|

Duration as PD |

–0.0440 (.3878) |

–0.1224 (.0157) |

–0.1233 (.0160) |

–0.1078 (.0354) |

–0.1122 (.0289) |

|

# of residents |

0.0577 (.2786) |

0.0812 (.1252) |

0.1109 (.0381) |

0.0953 (.0752) |

0.0714 (.1832) |

|

URiM residents |

0.0181 (.7275) |

0.0378 (.4635) |

0.0370 (.4763) |

0.1096 (.0352) |

0.0698 (.1806) |

|

URiM faculty |

0.1708 (.0007) |

0.1583 (.0016) |

0.1383 (.0064) |

0.1306 (.0102) |

0.1380 (.0067) |

|

URiM patients |

0.0517 (.3117) |

0.1538 (.0025) |

0.0793 (.1220) |

0.1321 (.0101) |

0.1189 (.0208) |

|

Community size |

0.0262 (.5952) |

0.1773 (.0003) |

0.0930 (.0605) |

0.0721 (.1458) |

0.0945 (.0571) |

Abbreviations: PD, program director; URiM, underrepresented in medicine

Table 3. Correlations Between Aspects of Holistic Review.

|

Understanding |

Agreement |

Screening |

Interviewing |

Ranking |

|

|

Understanding |

1.00 |

0.48 |

0.64 |

0.55 |

0.52 |

|

Agreement |

1.00 |

0.60 |

0.54 |

0.54 |

|

|

Screening |

1.00 |

0.62 |

0.61 |

||

|

Interviewing |

1.00 |

0.68 |

|||

|

Ranking |

1.00 |

Note: All correlations have P values <.0001.

DISCUSSION

The data suggest that the majority of FMRPs not only perceive the use of holistic review favorably in the selection process for residents but also currently implement it throughout the process. These programs also were found to have higher rates of URiM patients, residents, and faculty compared to programs that did not prefer holistic review.

These findings are reflective of a scoping review that found that US residencies and fellowships aiming to increase their diversity, especially their proportion of URiM makeup, are using holistic review as one of their strategies. 22 Specific programs, such as the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston Internal Medicine Residency Program 23 and the Boston Medical Center Family Medicine Residency Program, 24 have reported increased diversity after their own implementation of holistic review.

To our surprise, newer PDs reported using holistic review to a greater extent than more experienced PDs. This might be due to holistic review being a more recent approach to recruitment compared to the traditional recruitment process that emphasized academic metrics. Given that newer programs were disqualified from the survey, the use of holistic review possibly was underestimated if those programs are creating selection criteria during a time when holistic review is becoming more utilized.

Our study had several limitations. First, given the nature of inquiry, some social desirability bias in the responses is likely. For instance, the survey called for self-assessments of understanding holistic review rather than an objective measure of understanding—potentially overestimating how well PDs understand it. Similarly, PDs self-reported at what stages holistic review was used, but the study did not assess how it was applied. Given the limited number of survey questions, additional studies are needed to assess how programs apply holistic review to each process of the application cycle. Second, while consistent with many national surveys, the overall survey response rate was only 44%, which may represent some bias in sampling and limit the generalizability of the findings. Third, the structure of CERA surveys allows only one answer per question and does not allow “all applicable” responses, limiting nuance in the response options provided by respondents. Furthermore, no free text option was offered for those who answered “Other” to barriers of holistic review implementation, limiting our ability to explore other potentially important program aspects. We note that our survey item designed to elicit respondents’ level of agreement with using a holistic review approach included the word “agree” in the question stem and had five levels of ordinal agreement across which respondents could differentiate levels of agreement; this wording may have been confusing to some respondents. However, the item appeared to function appropriately because we had a good distribution across response options. Because causality and directionality are not possible with cross-sectional data, this study’s conclusions can be limited only to associations. More elaborate study designs would be necessary to assess the direction of associations, including higher endorsement and use of holistic review in larger programs/communities and programmatic/community diversity resulting from the existing diversity or the driving of diversity from the result of the use of holistic review.

On the other hand, this study was the first to demonstrate just how prevalent and favorable the majority of FMRPs are to holistic review. However, the increased number of applicants and increased resources needed to implement holistic review are important barriers that FMRPs need to tackle. The mapping of experiences, attributes, and academic metrics to mission values also may be a new experience for some FMRPs. As a result, disseminating models and interdepartmental and system (eg, AAMC, Association of Departments of Family Medicine, Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, AAFP) mentorship would be beneficial. Exploring partnerships and sharing of resources across institutions already implementing holistic review, participating in workshops, 25 and using mission-based filters in the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) 26 are some opportunities that could help overcome these barriers. With the 2023 ERAS application updates, geographic preferences and impactful experiences also can potentially help programs implement holistic review.

Future work should examine the specific scoring rubrics of FMRPs that use holistic review to assess how it is being implemented. Additionally, quantifying the increased cost of holistic review would be helpful, given increasingly tight hospital budgets and pressure on residencies to cut costs. Cost could also be a metric to increase accountability in future graduate medical education payment reform. While this study examined the associations of holistic review with programs’ racial and ethnic diversity, other diversity factors that are historically minoritized in medicine—such as gender identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, rural status, resilience, and distance traveled—should also be evaluated.

CONCLUSIONS

In the aftermath of the Supreme Court decision to end affirmative action in college admissions, 17 many residency programs are seeking methods to assess an applicant’s diverse lived experiences. The holistic review approach, which considers experiences and attributes in addition to academic metrics, can incorporate an applicant’s lived experiences of resilience and distance traveled to invite a diverse pool of applicants for interview selection, independent of race and ethnicity. Increasing the diversity of the physician workforce has been recognized as having an important role in addressing the large racial and ethnic health outcomes disparities in the United States. Our study revealed that holistic review has increasingly become a purposeful recruitment tool for FMRPs to enhance their diversity makeup, particularly in groups that are considered URiM. Use of holistic review has the potential to drive more URiM representation into the physician workforce. 18 Ultimately, this effort has the potential to significantly improve the health and satisfaction of groups that have been historically marginalized and the US patient population as a whole.

References

- 1.Laditka J N. Physician supply, physician diversity, and outcomes of primary health care for older persons in the United States. Health Place. 2004;10:231–244. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jetty A, Jabbarpour Y, Pollack J, Huerto R, Woo S, Petterson S. Patient-physician racial concordance associated with improved healthcare use and lower healthcare expenditures in minority populations. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9(1):68–81. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00930-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Association of American Medical Colleges. AAMC. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xierali I M, Nivet M A. The racial and ethnic composition and distribution of primary care physicians. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(1):556–570. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marrast L M, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor D H, Mccormick D. Minority physicians’ role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):289–291. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeshita J, Wang S, Loren A W. Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024583. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen M J, Peterson E B, Costas-Muñiz R. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):117–140. doi: 10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. QuickFacts. US Census Bureau. 2023. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/faq/US/PST045222 https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/faq/US/PST045222

- 9.Wang T, Neill O, Newton T R, Hall W P, Eden K, A R. Racial/ethnic representation among American Board of Family Medicine certification candidates from 1970 to 2020. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(1):9–17. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2022.01.210322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Data Release and Research Committee Results of the 2018 NRMP Program Director Survey. National Resident Matching Program. 2018. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-2018-Program-Director-Survey-for-WWW.pdf https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-2018-Program-Director-Survey-for-WWW.pdf

- 11.Mcgaghie W C, Cohen E R, Wayne D B. Are United States Medical Licensing Exam Step 1 and 2 scores valid measures for postgraduate medical residency selection decisions. Acad Med. 2011;86(1):48–52. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ffacdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubright J D, Jodoin M, Barone M A. Examining demographics, prior academic performance, and United States Medical Licensing Examination scores. Acad Med. 2019;94(3):364–370. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witzburg R A, Sondheimer H M. Holistic review-shaping the medical profession one applicant at a time. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):565–566. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1300411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holistic review. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2022. https://www.aamc.org/services/member-capacity-building/holistic-review https://www.aamc.org/services/member-capacity-building/holistic-review

- 15.Talamantes E, Henderson M C, Fancher T L, Mullan F. Closing the gap-making medical school admissions more equitable. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(9):803–805. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1808582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grabowski C J. Impact of holistic review on student interview pool diversity. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2018;23(3):487–498. doi: 10.1007/s10459-017-9807-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v President and Fellows of Harvard College, No. 20–1199, slip op. Jun 29, 2023. https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/20-1199_hgdj.pdf https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/20-1199_hgdj.pdf

- 18.Igarabuza L, Gusoff G M, Maharaj-Best A C. SHARPening residency selection: implementing a systematic holistic application review process. Acad Med. 2024;99(1):58–62. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000005451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Health Resources and Services Administration. What is [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noether G E. Why Kendall tau? Teach Stat. 1981;3(2):41–43. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samara B, Randles R H. A test for correlation based on Kendall’s tau. Commun Stat Theory Methods. 1988;17(9):3,191–3,205. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mabeza R M, Christophers B, Ederaine S A, Glenn E J, Benton-Slocum Z P, Marcelin J R. Interventions associated with racial and ethnic diversity in US graduate medical education: a scoping review. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):2249335. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.49335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aibana O, Swails J L, Flores R J, Love L. Bridging the gap: holistic review to increase diversity in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94(8):137–138. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wusu M H, Tepperberg S, Weinberg J M, Saper R B. Matching our mission: a strategic plan to create a diverse family medicine residency. Fam Med. 2019;51(1):31–36. doi: 10.22454/FamMed.2019.955445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marvin R, Park Y S, Dekhtyar M. Implementation of the AAMC’s holistic review model for psychiatry resident recruitment. MedEdPORTAL. 2023;19:11299–11299. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swails J L, Adams S, Hormann M, Omoruyi E, Aibana O. Mission-based filters in the electronic residency application service: saving time and promoting diversity. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(6):785–794. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-21-00302.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]