Abstract

To inform research and practice with distressed couples, the current study was designed to examine patterns of change among distressed, help-seeking couples prior to receiving an intervention. Data from this study originate from 221 couples assigned to the waitlist control condition of a randomized controlled trial for couples seeking online help for their relationship. All couples self-selected into the online program and agreed to withhold seeking additional services for their relationship during the waitlist period. In contrast to prior findings, results from the current study indicated a general pattern of mean improvement in both self-reported relationship functioning (e.g., increased relationship satisfaction, partner emotional support) and self-reported individual functioning (i.e., decreased psychological distress, anger) over the six-month waitlist period. Nonetheless, the majority of couples continued to remain relationally distressed despite these improvements. Findings from the study indicate that distressed couples can, in fact, exhibit some degree of improvement absent of intervention. At the same time, overall levels of distress remained elevated, indicating that these improvements are not sufficient to result in high levels of functioning and suggesting that many distressed couples may benefit from empirically-supported programs to realize greater gains. These results also highlight and underscore the importance of including control conditions in studies examining the efficacy of relationship interventions with distressed couples in order to ensure that any observed improvements in relationship functioning are attributable to the intervention rather than to naturally occurring changes.

Keywords: Couples, Relationship Distress, Relationship Satisfaction, Couple Intervention, Waitlist

Effectively intervening with couples experiencing relationship distress remains a focal area of interest for scholars, practitioners, and policymakers (for reviews, see Bradbury & Bodenmann, 2020; Stanley et al., 2020). Such efforts require, in part, an accurate understanding of the naturally-occurring dynamics and trajectories of distressed couples. Nonetheless, important questions remain regarding patterns of change among distressed couples prior to receiving services. For instance, in the absence of intervention, does relationship distress continue to worsen, stabilize, or improve? Relatedly, is it possible that some couples’ distress might remit without outside intervention? These questions have important implications both conceptually for understanding how relationship distress unfolds over time and practically for the design and delivery of relationship interventions (e.g., whether control groups are necessary to assess program effects, which couples should be prioritized for treatment), but have yet to be addressed empirically. Accordingly, the current study used longitudinal data from a national sample of distressed, help-seeking couples assigned to the waitlist control condition of an online intervention in order to understand the ways in which relationship and individual functioning change over time within this specific sample of couples.

Prior research has suggested that distressed couples’ functioning is unlikely to improve on its own. Baucom et al. (2003) meta-analyzed changes in marital quality among couples assigned to waitlist control groups in 17 randomized controlled trials of behavioral couple therapy. On average, there was no significant change (mean effect size = −.06), indicating that there are not notable improvements in marital quality among distressed couples awaiting couple therapy. A more recent meta-analysis by Roddy et al. (2020) reported similar findings, with couples assigned to waitlists in couple therapy trials demonstrating no significant changes over time in relationship satisfaction (Hedge’s g = 0.12), emotional intimacy (Hedge’s g = 0.09), or observed communication (Hedge’s g = −0.11); as one exception, waitlist couples did report small but significant improvements in relationship behaviors (Hedge’s g = 0.36). These findings are also generally consistent with longitudinal research showing that relationship satisfaction generally declines or remains stable over time among community samples (Lavner & Bradbury, 2010; Proulx et al., 2017; VanLaningham et al., 2001).

Although these results seem to suggest that the relationship functioning of distressed help-seeking couples is unlikely to get better, there is reason to believe that these findings are incomplete. First, although the general mean pattern in the meta-analysis of waitlist couples was one of no change, there were a range of effect sizes observed across studies. Specifically, effect sizes ranged from a decline in functioning of −.73 to an increase in functioning of .31 in Baucom and colleagues’ (2003) meta-analysis, with a similarly large range (−.38 to .89) in the more recent meta-analysis by Roddy and colleagues (2020). Additionally, because the sample sizes were relatively small (ranging from 5–33 in Baucom and from 5–20 in Roddy), estimates were less robust and there was less power to detect effects. Second, partners seeking couple therapy are likely to be quite distressed and typically only seek treatment after an extended period of declining relationship functioning (e.g., Jarnecke et al., 2020; Owen et al., 2019). This suggests that this group may be especially unlikely to improve (and arguably makes it striking that the mean pattern was one of stability) and that they may not represent all “help-seeking couples.” Indeed, it is more common for distressed help-seeking couples to seek assistance for their relationship through means other than couple therapy, including reading self-help books, looking up information online, or seeking advice from friends or family (Stewart et al., 2016). As a group, these (non-therapy-seeking) couples may experience less persistent distress relative to couples who take the step of seeking out couple therapy—which is one that a minority of even divorcing couples take (C. A. Johnson et al., 2002)—and may thus show greater potential for improvement in their functioning over time.

Indeed, other work suggests that improvements in functioning are possible among distressed couples. First, unpublished analyses using longitudinal data from the National Survey of Families and Households indicated that 62% of spouses who were unhappy at baseline but remained married 5 years later (77% of the unhappy group) reported being happy in their marriage at follow-up (Waite & Luo, 2002, as cited in Fincham et al., 2007). Second, in another large national longitudinal study, 28% of participants reported that they had previously thought their marriage was in trouble but not in the past 6 months (and 88% of this group reported that they were glad they were still married) and 31% of individuals who reported recent thoughts of divorce reported no such ideation one year later (Hawkins et al., 2017). Third, although there is little evidence of improvements in relationship satisfaction among community samples, there is evidence of improvements in other dimensions of relationship functioning (e.g., relationship happiness, couple conflict), particularly among couples with low levels of marital quality and/or among couples who had undergone declines in marital quality (Proulx et al., 2017). Together, these findings suggest that couples may be able to undergo some type of self-repair following periods of distress, consistent with the idea of “spontaneous remission” of marital discord (Fincham et al., 2007). More generally, remission of distress is not uncommon—for example, a review of waitlist and cohort studies of major depression suggest that 23% of untreated cases will remit within 3 months, 32% will remit within 6 months, and 53% will remit within 12 months (Whiteford et al., 2013)—again raising the possibility that distressed help-seeking couples will show some improvement over time.

The current study aimed to build on this work using five waves of data from 221 couples assigned to a six-month waitlist control condition of a randomized controlled national trial for couples seeking online help for their relationship (see Doss et al., 2020 for more information). Importantly, these couples agreed to not seek help from other sources during the 6-month waitlist period, ensuring that the observed patterns are not attributable to these other sources. We sought to better understand stability and change in partners’ relationship and individual functioning as they awaited the intervention. The study design has several notable advantages over previous work. First, its exclusive focus on a help-seeking sample, of which more than 85% of participants were distressed at baseline, allowed for a nuanced understanding of what happens to distressed, help-seeking couples’ relationships in the absence of intervention. This is a notable contrast to community-based samples and to studies using waitlist control conditions in trials of relationship education, which can include a mix of distressed couples and well-functioning couples seeking relationship enhancement. Second, the sample size of the current study is more than seven times larger than the largest waitlist control study from the couple therapy literature (Baucom et al., 2003; Roddy et al., 2020), providing greater population coverage and more power to detect small effects. Third, multiple waves of data ensured that any improvement reflected lasting change rather than a simple regression-to-the-mean effect. Fourth, assessing multiple domains of relationship and individual functioning, including relationship satisfaction, relationship instability, partner emotional support, destructive communication, partner aggression, psychological distress, and anger, provides a comprehensive more complete assessment of relationship and individual well-being. Doing so is important given previous conflicting findings regarding improvements in satisfaction and other dimensions of relationship functioning (Proulx et al., 2017), and allows for the examination of effects on individual functioning, which is highly comorbid with relationship distress (e.g., Proulx et al., 2007) but has yet to be considered in studies of change among waitlist controls in couple interventions. In summary, we examined the following research questions:

Do waitlisted couples show significant changes—for better or for worse—in their relationship and individual functioning over a 6-month waitlist period?

Do some couples demonstrate “remission,” such that they were initially classified as relationally distressed but are no longer distressed at 6-month follow-up?

Do changes in relationship and individual functioning occur even among couples who remain distressed from baseline to follow-up? Examining this question allows us to ensure that any overall patterns of change were not disproportionately affected by couples whose distress remitted by follow-up.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data from this study originate from 221 couples (442 individuals) assigned to the waitlist control condition of a randomized controlled trial for couples seeking online help for their relationship (see Doss et al., 2020). Individuals could learn about the study through various means, including “organic” results from online search engines (e.g., searching “free marriage counseling” and clicking on a [non-advertised] search result), paid advertisements on search engines, social media advertisements, and word of mouth. After learning about the program, individuals who visited the program website were instructed to complete an online consent form followed by a screening questionnaire to determine eligibility. In order to be eligible to participate in the study, individuals had to be married, engaged, or cohabiting for at least six months. Participants were required to have a household income within 200% of the federal poverty line and live within the United States. Participants had to be between the ages of 18–64, agree not to seek alternative forms of treatment (e.g., couple therapy or self-help books) during the six months of their participation, and have high-speed internet access. Further, individuals had to fluently read and write in English and must not have ever participated in the relationship education programming implemented in this RCT. Potential participants were excluded for more severe forms of intimate partner violence (e.g., choked, beat up, forced sex upon, or threatened one another with a gun or a knife) and were also excluded if they were “quite,” “very,” or “extremely” afraid that their partner would physically hurt them during an argument.

A total of 742 couples met eligibility criteria and were enrolled in a three-arm randomized clinical trial (see Doss et al., 2020 for more details, including CONSORT diagram). Participant consent was obtained from an online consent form located on the project website that participants would complete as part of the online screening process. Following randomization, 247 couples were assigned to the waitlist condition. From the sample of 247 couples assigned to the waitlist condition, an additional 26 couples were removed for data analysis for the current study as they did not meet criteria for help-seeking status (i.e., were engaged and neither partner reported relationship satisfaction scores in the distressed range [n=12]1) or contain non-distinguishable dyadic data (i.e., same sex couples [n=14]), resulting in a final sample of 221 couples.

Of this sample, slightly more than half of participants (57%) were married, and 20% were engaged. On average, couples had been together for 6 years (Mdn = 5; SD = 5.76) and 72% had children. The vast majority of women (89%) and men (82%) endorsed initial relationship satisfaction scores in the distressed range (<13.5 on the Couple Satisfaction Index; Funk & Rogge, 2007). Women’s median age was 32 (M = 32.79; SD = 7.95) and men’s median age was 33 (M = 35.10; SD = 8.64). Concerning race and ethnicity, women and men were primarily White (74.2% and 88.2%, respectively) and non-Latino (9.0% of women and 11.8% of men reported Latino ethnicity). For highest level of education completed, 21.5% of women and 42.7% of men reported high school or less; 55.2% of women and 42.7% of men reported some college, technical training, or an Associate’s degree; and 23.2% of women and 14.6% of men reported a Bachelors or graduate degree. The majority of the sample was employed (63.3% of women and 81.4% of men), with 29.9% of women and 61.5% of men reporting full-time (>34 hours per week) employment. Median past month income was $500-$1000 for women and $1001-$2000 for men (both ranged from Less than $500 to More than $5000).

Individuals in the waitlist condition completed a total of five surveys at similar time intervals as those in the intervention condition: baseline, 1-month follow-up, 2-month follow-up, 4-month follow-up, and 6-month follow-up. Respective retention for women and men was 98% and 98% at Wave 2, 95% and 95% at Wave 3, 94% and 92% at Wave 4, and 90% and 89% at Wave 5. All procedures were approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (#NCT02806635) prior to the initiation of data collection.

Measures

Relationship Functioning

Five relationship characteristics reflecting cognitive and behavioral processes within the relationship were assessed.

Relationship Satisfaction.

Relationship satisfaction was measured using the 4-item version of the Couple Satisfaction Index (Funk & Rogge, 2007); an example item is, “In general, how satisfied are you with your relationship?” The CSI-4 was developed using Item Response Theory and has strong convergence with other satisfaction measures (Funk & Rogge, 2007). Response options ranged from 0 = extremely unhappy to 6 = Perfect (question 1) and 0 = Not at all true to 5 = Completely (questions 2–4). The measure demonstrated very good reliability across waves (α from .89 to .93 for women and men). Responses were summed with higher scores indicating greater relationship satisfaction.

Relationship Instability.

Potential dissolution of the relationship was assessed using three items adapted from the Marital Instability Index (Edwards et al., 1987). Individuals were asked to report the frequency of past month thinking about the following three items: “The thought of ending my relationship has crossed my mind”, “I’ve thought my relationship might be in trouble”, and “How likely is it that you and your partner will break-up within the next year?” Response options ranged from 1 = Never in the past month to 5 = More than once a day (questions 1 and 2) and 1 = Very unlikely to 5 = Very likely (question 3). The measure demonstrated good reliability across waves (α from .84 to .91 for women and men). Items were summed such that higher scores indicated greater relationship instability.

Partner Emotional Support.

Participants’ reports of partner emotional support within the relationship were assessed using 5 items developed for the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) Supporting Healthy Marriage Initiative. Sample items included: “I can count on my partner/spouse to be there for me”, “My partner/spouse knows and understands me”, and “My partner/spouse expresses love and affection toward me.” Response options ranged from 1 = Strongly Agree to 4 = Strongly Disagree. The measure demonstrated good reliability across waves (α from .79 to .91 for women and men). Items were recoded and summed with higher scores indicating greater partner emotional support.

Destructive Communication.

The frequency of past-month destructive communication patterns was assessed using 7 items developed for the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) Supporting Healthy Marriage Initiative. Sample items included: “My partner/spouse was rude or mean to me when we disagreed” and “Our arguments became very heated.” Response options ranged from 1 = Never to 4 = Often. The measure demonstrated good reliability across waves (α from .87 to .92 for women and men). Items were summed with higher scores indicating more negative communication in conflict.

Partner Aggression.

Perpetration of physical aggression by one’s partner was assessed using 7 items created for this study in consultation with the National Domestic Violence Hotline. Response options were along a seven-point scale (0 = Never; 6 = More than 20 times). Individuals were asked to report “how often YOUR PARTNER has done the following things in the PAST MONTH (emphasis in original)”; sample items included “pushed or shoved”, “slapped”, and “punched me.” Internal consistency in the current sample was acceptable to good across waves (α from .61 to .93 for women and men), which was expected given the low base rate of occurrence for some of the items. Items were summed with higher scores indicating greater partner aggression.

Individual Functioning

Two types of individual-level psychosocial functioning were assessed: psychological distress and anger.

Psychological Distress.

Levels of psychological distress were assessed using 6 items from the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (Kessler et al., 2002). This scale asks respondents how frequently in the past 30 days they had felt: nervous; hopeless; restless or fidgety; so depressed that nothing could cheer them up; that everything was an effort; and worthless. Response options ranged from 1 = none of the time to 5 = all of the time. Internal consistency in the current sample was good across waves (α from .84 to .92 for women and men). Scores were summed, with higher scores indicating greater psychological distress.

Anger.

Levels of anger were measured using 5-items from the Anger subscale of the National Institutes of Health Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Emotional Distress battery (Pilkonis et al., 2011). Instructions were modified to prompt for anger not directed at the partner. Hence, individuals were asked, “How often have you felt the following ways in situations or with people OTHER THAN YOUR PARTNER?” (emphasis in original), with items such as: “I felt like I was ready to explode” and “I felt angry.” Response options ranged from 1 = never to 5 = always. Internal consistency was very good across waves (α from .90 to .92 for women and men). Scores were summed, with higher scores indicating greater anger.

Plan of Analysis

For our plan of analysis, we first examined trajectories of partners’ relationship and individual functioning over the 6-month waitlist period (Research Question 1). To do so, we analyzed a series of dyadic growth curves in a multilevel modeling framework using the HLM 6.0 computer program (Raudenbush et al., 2004). Growth curve analytic techniques allow for a two-level data analysis. Observation occasions (Level 1) are nested within individuals (Level 2). Each person’s relationship satisfaction is described by two parameters: an intercept (initial level of the variable) and a slope (rate of change over time). Level 2 examines between-subject differences in these parameters using individual-level predictors. Missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood estimation. Maximum likelihood estimation is unbiased when reasons for missingness are included in the model (i.e., missing at random), such as when missingness can be predicted by prior observed values or trajectories of change.

Data from male partners and female partners were estimated simultaneously within the same equations using the dual intercept and slope model outlined by Raudenbush, Brennan, and Barnett (1995). Time was centered at baseline so that the intercept terms (πf0 and πm0i) could be interpreted as the value at the initial assessment, with time measured in months from baseline (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, and 6 as time points). We used the following Level 1 equation for each outcome:

We conducted seven separate models, one for each outcome of interest described in the Measures section. In each of these models, the parameters of main interest were men’s and women’s mean rates of change. We also report variance in the slopes (reflecting the degree to which participants differ in their rates of change) as well as the covariance between women’s intercept and slope parameters and between men’s intercept and slope parameters (reflecting the degree to which the rates of change are associated with participants’ initial values). Consistent with previous work (Doss et al., 2020), effect size for rate of change similar to Cohen’s d was calculated by multiplying the slope parameter with the study duration (i.e., 6 months for this study) to determine the total amount of change over follow-up, then dividing this product by the standard deviation of the measure at baseline (also see Morris, 2007).

To examine remission (Research Question 2), we examined the percentage of participants who met cut-off scores for relationship distress at the beginning and end of the 6-month waitlist period as defined by criteria on the Couple Satisfaction Index (i.e., < 13.5). Differences in percentage distressed at the first and last time point were tested using paired-sample t-tests among the sample of individuals who responded at both time points. Additionally, from the subset of individuals who began the study relationally distressed, we examined the percentage that remained distressed and those that were no longer distressed at the end of the waitlist period. Lastly, we conducted a series of growth curve analyses examining change in each of the outcome measures for partners who stayed distressed and partners who were no longer distressed at the end of the 6-month waitlist period (Research Question 3). These analyses were undertaken as a mean to examine the robustness of the mean-level patterns identified in Research Question 1 and to evaluate the extent to which change was still observed among participants who began and ended the study relationally distressed.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations of study measures at baseline are summarized in Supplemental Table 1. Within-individual correlations among study variables were all in the expected direction, and correlations between partners were all significant and small to moderate in magnitude. Mean scores on relationship satisfaction (8.05 and 9.64 for women and men, respectively) were in the distressed range on the CSI (< 13.5), and mean scores on psychological distress (16.62 and 14.88 for women and men, respectively) were in the distressed range on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (≥ 13).

Mean Trajectories of Relationship and Individual Functioning

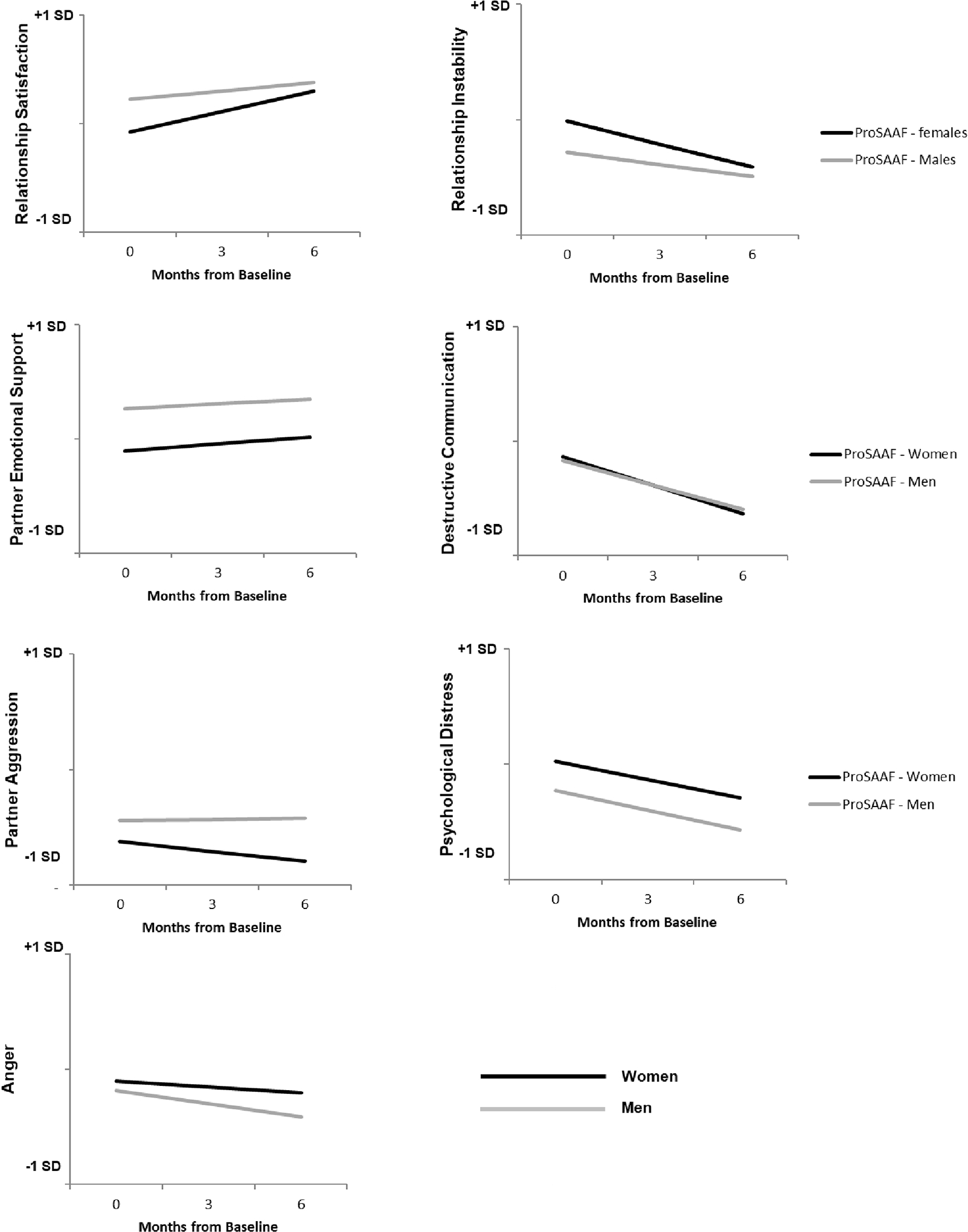

Results of unconditional dyadic growth curves are shown in Table 1 and displayed in Figure 1. On average, men and women showed small to moderate improvements in most domains. Specifically, regarding relationship functioning, the mean growth trajectory showed a small increase in relationship satisfaction (dwomen = 0.38; dmen = 0.15), as well as a small decrease in relationship instability (dwomen = −0.39; dmen = −0.22) and a moderate decrease in destructive communication (dwomen = −0.48; dmen = −0.43). Partner emotional support and partner aggression did not show significant change over time for women or men. Concerning individual functioning, women and men reported small declines over time in psychological distress (dwomen = −0.32; dmen = −0.34) and men reported small declines in anger (dmen = −0.23).

Table 1.

Slope Parameter Estimates (N = 221 couples)

| Variable | Estimate (B) | se | Effect Size | Variance (σ2) | r Int-Slope |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Women | |||||

| Relationship satisfaction | 0.28** | .05 | 0.38 | 0.24** | −0.26 |

| Relationship instability | −0.22** | .04 | −0.39 | 0.18** | −0.36 |

| Partner emotional support | 0.07 | .04 | 0.13 | 0.16** | −0.17 |

| Destructive communication | −0.37** | .05 | −0.48 | 0.25** | −0.07 |

| Partner aggression | −0.04 | .02 | −0.14 | 0.01 | −0.86a |

| Psychological distress | −0.29** | .05 | −0.32 | 0.29** | −0.09 |

| Anger | −0.07 | .05 | −0.09 | 0.15** | −0.22 |

| Men | |||||

| Relationship satisfaction | 0.11* | .05 | 0.15 | 0.29** | −0.26 |

| Relationship instability | −0.12** | .04 | −0.22 | 0.14** | −0.28 |

| Partner emotional support | 0.05 | .04 | 0.09 | 0.16** | −0.17 |

| Destructive communication | −0.32** | .06 | −0.43 | 0.29** | −0.19 |

| Partner aggression | −0.00 | .03 | −0.00 | 0.14** | 0.09 |

| Psychological distress | −0.31** | .06 | −0.34 | 0.34** | −0.16 |

| Anger | −0.17** | .05 | −0.23 | 0.13** | −0.05 |

p < .05 (two-tailed).

p < .01 (two-tailed).

Notes. Int = Intercept.

The high magnitude of this correlation is attributable to the very small variance for women’s reports of partner aggression and can be interpreted as indicating that the slope is not providing unique information.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of relationship and individual functioning over time for women and men. Y-axis range set to +/−1 Standard Deviation (SD) of averaging men’s and women’s baseline SDs.

Nearly all mean rates of change were characterized by significant between-individual variability, indicative of variation in individual trajectories. For example, the estimated 10th percentile participant experienced a moderate to large decline in relationship satisfaction (dwomen = −0.48; dmen = −0.77), whereas the estimated 90th percentile participant experienced a very large improvement (dwomen = 1.25; dmen = 1.07; see Supplemental Table 2 for 80% coverage intervals and accompanying effect sizes for relationship and individual trajectories). Intercept-slope covariance was negative for most outcomes (see Table 1), indicating that individuals with higher initial distress tended to experience more improvement, whereas those with lower initial distress tended to have less improvement/more decline.

Changes in Relational Distress Classification Over Time

Next, we examined the extent to which participants’ relational distress classification, on the basis of scores on the CSI-4, changed over the course of the study. To do so, we focused on the subgroup of participants who completed assessments at baseline and at 6-month follow-up (n = 199 women and 196 men). Of this group, 89% of women and 80% of men were relationally distressed at baseline and 75% of women and 71% of men were relationally distressed at 6-month follow-up. McNemar tests (given the dichotomous variable) indicated significantly fewer relationally distressed individuals at six-month follow-up compared to baseline levels for women and for men (both p < .01). Among the subset of participants who were distressed at baseline (n = 177 women and 157 men), 18% of women (n = 32) and 21% of men (n = 33) were no longer classified as distressed at 6-month follow-up. At the couple level, 188 couples had both partners complete baseline and at 6-month follow-up assessments, with 75% of these couples (n = 140) having both partners characterized by relationship distress at baseline. Of these 140 couples in which both partners began the study relationally distressed, the majority of couples (69%; n = 96) continued to have both partners classified as distressed at 6-month follow-up, 26% (n = 36) had only one partner classified as distressed at 6-month follow-up, and 6% (n = 8) had neither partner classified as distressed at 6-month follow-up.

Change in Relationship and Individual Functioning Among Initially Distressed Partners

Lastly, we examined trajectories of relationship and individual functioning among participants who were initially distressed, estimating a series of growth curves for four separate subgroups: (1) women no longer distressed at 6-month follow-up (n = 33), (2) men no longer distressed at 6-month follow-up (n = 34), (3) women still distressed at 6-month follow-up (n = 144), and (4) men still distressed at 6-month follow-up (n = 123). Results are summarized in Table 2. As expected based on their classification, women and men who were initially distressed but no longer distressed at follow-up reported significant improvements in all domains (with the exception of partner aggression), with effect sizes in the medium to large range (women: |0.51–2.46|; men: |0.35–2.13|). More importantly, the subset of participants who were still distressed at 6-month follow-up also reported significant improvements in several domains, though results were more robust for women than men and effect sizes were small in magnitude. Specifically, women who were still relationally distressed at 6-month follow-up nonetheless reported increases in relationship satisfaction (d = 0.36) and decreases in relationship instability (d = −0.36), destructive communication (d = −0.40), and psychological distress (d = −0.31) over the course of the study; reports of partner emotional support, partner aggression, and anger did not change significantly. Men who were still relationally distressed at 6-month follow-up reported decreases in destructive communication (d = −0.43) and psychological distress (d = −0.36) over the course of the study, but no significant changes in relationship satisfaction, relationship instability, partner emotional support, partner aggression, or anger.

Table 2.

Slope Parameter Estimates of Select Subsamples

| Variable | Estimate (B) | se | Effect Size | Variance (σ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Distressed at Baseline and No Longer Distressed at 6-Month Follow-Up | ||||

| Women (N = 33) | ||||

| Relationship satisfaction | 1.06** | 0.12 | 2.46 | 0.11 |

| Relationship instability | −0.57** | 0.11 | −1.13 | 0.14* |

| Partner emotional support | 0.49** | 0.11 | 1.15 | 0.25** |

| Destructive communication | −0.93** | 0.17 | −1.30 | 0.42** |

| Partner aggression | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.15 | 0.03** |

| Psychological distress | −0.58** | 0.16 | −0.70 | 0.23+ |

| Anger | −0.44** | 0.14 | −0.51 | 0.27* |

| Men (N = 34) | ||||

| Relationship satisfaction | 0.89** | 0.11 | 2.13 | 0.13 |

| Relationship instability | −0.49** | 0.08 | −0.93 | 0.10* |

| Partner emotional support | 0.57** | 0.08 | 1.29 | 0.06 |

| Destructive communication | −0.75** | 0.15 | −0.88 | 0.27* |

| Partner aggression | −0.05 | 0.07 | −0.17 | 0.01 |

| Psychological distress | −0.68** | 0.16 | −0.85 | 0.39** |

| Anger | −0.26* | 0.14 | −0.35 | 0.28** |

| Distressed at Baseline and 6-Month Follow-Up | ||||

| Women (N = 144) | ||||

| Relationship satisfaction | 0.19** | 0.05 | 0.36 | 0.17** |

| Relationship instability | −0.18** | 0.05 | −0.36 | 0.17** |

| Partner emotional support | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.11** |

| Destructive communication | −0.28** | 0.05 | −0.40 | 0.13** |

| Partner aggression | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.15 | 0.05** |

| Psychological distress | −0.28** | 0.07 | −0.31 | 0.24** |

| Anger | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.09* |

| Men (N = 123) | ||||

| Relationship satisfaction | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.19** |

| Relationship instability | −0.07 | 0.05 | −0.14 | 0.14** |

| Partner emotional support | −0.05 | 0.04 | −0.10 | 0.10** |

| Destructive communication | −0.24** | 0.07 | −0.43 | 0.17** |

| Partner aggression | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.13** |

| Psychological distress | −0.32** | 0.07 | −0.36 | 0.30** |

| Anger | −0.11 | 0.06 | −0.15 | 0.00 |

p < .05 (two-tailed).

p < .01 (two-tailed).

Discussion

The current study aimed to examine patterns of change among distressed, help-seeking couples prior to any intervention. Given the personal and societal costs of relationship distress and dissolution, this demographic remains a key focal area for policy and services, and scholars have called for additional basic research with this population of couples in order to inform programming and services designed for them (e.g., M. D. Johnson, 2012; M. D. Johnson & Bradbury, 2015). From a sample of 221 couples assigned to the waitlist control condition of an online couple intervention, results from the current study highlight a general pattern of mean improvement in relationship and individual functioning over the six-month waitlist period. This pattern was observed in both men and women and appeared even among individuals who continued to remain relationally distressed at the end of the waitlist period. Although there was significant heterogeneity in these patterns of change, that the mean-level pattern was one of improvement is noteworthy.

Findings from the study indicate that clinically distressed couples can, in fact, exhibit some degree of improvement absent of intervention. Notably, this pattern was observed across multiple domains of relationship functioning as well as individual functioning. These findings align with prior work involving community samples of couples, which similarly noted improvements in domains of relationship functioning among couples with low levels of marital quality (e.g., Hawkins et al., 2017; Proulx et al., 2017). However, these results diverge from previous meta-analytic findings indicating a lack of change in couples assigned to the waitlist condition in randomized controlled trials of couple therapy (Baucom et al., 2003; Roddy et al., 2020). Specifically, mean effect sizes of change were small to moderate in the current study (.18 < d < .49) and roughly twice as large in magnitude as observed among waitlist/control couples in studies of couple therapy (Roddy et al., 2020). These differences may be due to the fact that couples who seek couple therapy generally do so only after an extended period of distress (e.g., Owen et al., 2019), suggesting that their distress may be more stable than that observed in community samples or than that among the many couples who pursue alternate forms of assistance for their relationship such as the online services studied here (Stewart et al., 2016).

In stating these average improvements over time, it is worth noting that there was significant between-individual variability in trajectories of relationship and individual functioning for nearly all outcomes in the study. Coverage intervals indicated that some individuals experienced very large improvements, and some clearly got worse. As such, it is important to remember that although mean patterns exist, help-seeking couples are not a monolithic group, and, left to themselves, demonstrate significant heterogeneity in patterns of change. Study findings also provide some empirical support for the “spontaneous remission of relationship distress” (Fincham et al., 2007; also see Hawkins et al., 2017). Specifically, approximately 20% of men and women were distressed at baseline but were no longer distressed at follow-up.

Although these patterns are notable, they also indicate that, despite mean-level improvements, the majority of couples continued to struggle. As such, the overall pattern of change in this study is one of improvement but not remission. Accordingly, findings should not be interpreted as indicating that many couples no longer need services—intervention is likely warranted with the majority of couples experiencing relationship distress and seeking help for their relationships. In other words, the small mean improvements, in combination with the majority of participants remaining distressed, suggest the need for intervention or outside services for the average couple in this situation.

Current results also highlight the importance of timing of recruitment (and potential intervention). As reported elsewhere, the majority of individuals who sought to enroll in this study learned about it from the results of an online search or social media (Barton, Hatch, et al., 2020). These individuals were actively seeking out help for their relationship and, as such, were perhaps at a point in time when their relationship was more amenable to change. This introduces the important question of whether, like child-focused interventions, there are particular “developmental windows” in the course of committed relationships when intervention efforts may be more needed and/or more likely to induce change. As this window will likely vary between couples and not uniformly appear at a certain relationship ‘age,’ newly-emerging Just in Time Adaptive Interventions (JITAIs) from the prevention science field may be useful by providing more tailored and time-sensitive programming to individuals and couples (Nahum-Shani et al., 2018).

As another key takeaway, current results also highlight the importance of including some sort of control condition in relationship intervention studies with distress couples. This recommendation stands in contrast to previous advice arguing against the necessity of this type of comparison group in couple therapy (Baucom et al., 2003). The current findings, however, suggest that in the absence of a comparison group, limited conclusions can be drawn given the need to differentiate gains specific to the intervention versus those that may occur naturally among help-seeking couples. Findings from the relationship education/couple prevention literature similarly highlight the importance of control conditions to contextualize program effects. In one prior randomized prevention trial with non-help-seeking low-income couples, there was a general decline in relationship quality over time, such that significant program effects were primarily in the form of stability and preventing decline over time rather than promoting improvements in absolute terms (Barton et al., 2018). Still other work indicates that couples in an active control group (a one-session relationship awareness condition in which couples watched and discussed a movie together and were then encouraged to continue doing so at home) performed as well relative to a no-treatment control as couples assigned to one of two skills-based prevention programs (Rogge et al., 2013). Collectively, these findings underscore the continued need for control conditions in couple intervention studies in order to accurately quantify program effects.

Various limitations of the study merit consideration. First, we do not have any data on couples’ relationship functioning prior to their seeking services so we cannot position these increases within the overall trajectory of the relationship or determine the degree to which baseline levels reflected temporary or longstanding distress. Proulx and colleagues (2017) noted a general pattern of a marital decline preceding marital improvement and that improvement rarely rebounded to initial levels, raising the possibility that these are relative improvements in some respects and relative declines in others. Second, eligibility requirements required dyadic participation, resulting in a truncated sample with those individuals experiencing the most relationship distress being omitted (Barton, Hatch, et al., 2020; also see Barton, Lavner, et al., 2020 for similar findings with non-intervention studies of romantic dyads). Relatedly, the ability of both partners to commit to a program at the onset of enrollment demonstrates some degree of commitment to the relationship and mutually signing up for an intervention may elicit some non-specific effects like greater appreciation for the partner and optimism about the future of the relationship that would not appear in a purely basic science, longitudinal study of distressed couples. Third, all outcomes were self-report. Observational data and/or observer ratings would provide another window into the relative degree of change in individual and couple functioning over time. Fourth, the classification of couple distress was based solely on CSI-4 criteria; future research with more expansive self-report assessments or professional assessments would be valuable for determining distress classification. Fifth, as these analyses included solely different sex couples, generalization to same-sex couples is not immediately known. As a final consideration, we note that the current sample was composed of couples seeking help for their relationship who agreed that they would not seek assistance from other means (e.g., books, therapy) if they were assigned to the waitlist condition. Positively, this inclusion criteria eliminates potential confounding effects of other services in shaping trajectories. At the same time, this prohibition also could affect the type of couples who sought to enroll in the trial, with those who were most distressed potentially unwilling to make this commitment; caution is warranted to not generalize findings beyond this specific population (i.e., self-selected participants who agreed to participate in a wait-list control group online intervention, and agreed to not seek help for 6 months).

Notwithstanding these limitations, these findings indicate that individual and relationship functioning can improve among distressed couples even in the absence of intervention. An immediate area for future research is understanding why these improvements occur, particularly among couples that demonstrated the most pronounced improvements. One possibility, as previous research has theorized (Fincham et al., 2007), is that some couples may possess particular capabilities or capacities such as commitment, forgiveness, and a transcendental view of the relationship that facilitate this recovery. Another possibility is that changes in couples’ lived context – particularly the amount of stress the couple is experiencing – may account for such recovery. A third possibility is that the decision to seek out help and subsequently knowing that help is on the horizon may instill couples with a sense of hope and confidence about the potential for future improvement. Even the agreement of both partners to participate in a program together could foster a sense of togetherness and mutual commitment to the relationship. Consequently, the conversations required of a couple to mutually agree to enroll in this type of program may, by itself, be part of the repair process. In other words, the decision to seek help might initiate communication and signal commitment between partners that serves as a catalyst for positive change. As these three possibilities are not mutually exclusive, various combinations of them may also appear in different couples. Future research can also consider more long-term follow-up of these couples to identify whether mean trends continue in the same direction and, for couples who improved, whether these improvements were maintained or if they subsequently deteriorated and returned to a distressed state.

In summary, results from the current study indicate that help-seeking couples can exhibit some degree of positive change in multiple areas absent of intervention. The mean change, however, is small and many couples remain relationally distressed. Additional research is needed into the dynamics of these couples in order to provide a strong empirical base from which innovative programming can be developed that fosters positive, lasting change among couples experiencing relationship distress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number Grant Number 90FM0063 to Brian Doss from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Administration of Children and Families. Dr. Brian Doss is a co-inventor of the intellectual property used in this study and an equity owner in OurRelationship LCC.

Footnotes

This criterion was designed to eliminate non-distressed engaged couples who enrolled for premarital education services. For instance, in Texas, the OurRelationship program is listed as one of the approved providers of premarital education for engaged couples that permits a discount on their marriage license.

References

- Barton AW, Beach SRH, Wells AC, Ingels JB, Corso PS, Sperr MC, Anderson TN, & Brody GH (2018). The Protecting Strong African American Families program: A randomized controlled trial with rural African American couples. Prevention Science, 19(7), 904–913. 10.1007/s11121-018-0895-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton AW, Hatch SG, & Doss BD (2020). If you host it online, who will (and will not) come? Individual and partner enrollment in a web-based intervention for distressed couples. Prevention Science, 21(6), 830–840. 10.1007/s11121-020-01121-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton AW, Lavner JA, Stanley SM, Johnson MD, & Rhoades GK (2020). “Will you complete this survey too?” Differences between individual versus dyadic samples in relationship research. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(2), 196–203. 10.1037/fam0000583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baucom DH, Hahlweg K, & Kuschel A (2003). Are waiting-list control groups needed in future marital therapy outcome research? Behavior Therapy, 34(2), 179–188. 10.1016/S0005-7894(03)80012-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury TN, & Bodenmann G (2020). Interventions for Couples. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 16(1), 99–123. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-071519-020546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Knopp K, Roddy MK, Rothman K, Hatch SG, & Rhoades GK (2020). Online programs improve relationship functioning for distressed low-income couples: Results from a nationwide randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(4), 283–294. 10.1037/ccp0000479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JN, Johnson DR, & Booth A (1987). Coming Apart: A Prognostic Instrument of Marital Breakup. Family Relations, 36(2), 168–170. 10.2307/583948 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Stanley SM, & Beach SRH (2007). Transformative Processes in Marriage: An Analysis of Emerging Trends. Journal of Marriage & Family, 69(2), 275–292. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00362.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk JL, & Rogge RD (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the Couples Satisfaction Index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 572–583. 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins AJ, Galovan AM, Harris SM, Allen SE, Allen SM, Roberts KM, & Schramm DG (2017). What Are They Thinking? A National Study of Stability and Change in Divorce Ideation. Family Process, 56(4), 852–868. 10.1111/famp.12299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarnecke AM, Ridings LE, Teves JB, Petty K, Bhatia V, & Libet J (2020). The path to couples therapy: A descriptive analysis on a veteran sample. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 9(2), 73–89. 10.1037/cfp0000135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CA, Stanley SM, Glenn ND, Amato P, Nock SL, Markman HJ, & Dion MR (2002). Marriage in Oklahoma: 2001 baseline statewide survey on marriage and divorce. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MD (2012). Healthy marriage initiatives: On the need for empiricism in policy implementation. American Psychologist, 67(4), 296–308. 10.1037/a0027743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MD, & Bradbury TN (2015). Contributions of Social Learning Theory to the promotion of healthy relationships: Asset or liability? Journal of Family Theory & Review, 7(1), 13–27. 10.1111/jftr.12057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SLT, Walters EE, & Zaslavsky AM (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. 10.1017/S0033291702006074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavner JA, & Bradbury TN (2010). Patterns of change in marital satisfaction over the newlywed years. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1171–1187. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00757.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SB (2007). Estimating Effect Sizes From Pretest-Posttest-Control Group Designs. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 364–386. 10.1177/1094428106291059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nahum-Shani I, Smith SN, Spring BJ, Collins LM, Witkiewitz K, Tewari A, & Murphy SA (2018). Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions (JITAIs) in Mobile Health: Key Components and Design Principles for Ongoing Health Behavior Support. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 52(6), 446–462. 10.1007/s12160-016-9830-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ, & Allen ES (2019). Treatment-as-Usual for Couples: Trajectories Before and After Beginning Couple Therapy. Family Process, 58(2), 273–286. 10.1111/famp.12390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, & Cella D (2011). Item Banks for Measuring Emotional Distress From the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): Depression, Anxiety, and Anger. 18(3), 263–283. 10.1177/1073191111411667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proulx CM, Ermer AE, & Kanter JB (2017). Group-Based Trajectory Modeling of Marital Quality: A Critical Review. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9(3), 307–327. 10.1111/jftr.12201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Proulx CM, Helms HM, & Buehler C (2007). Marital quality and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3), 576–593. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00393.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Brennan RT, & Barnett RC (1995). A multivariate hierarchical model for studying psychological change within married couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 9(2), 161–174. 10.1037/0893-3200.9.2.161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, & Congdon R (2004). HLM 6 for Windows [Computer software]. Scientific Software International, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Roddy MK, Walsh LM, Rothman K, Hatch SG, & Doss BD (2020). Meta-analysis of couple therapy: Effects across outcomes, designs, timeframes, and other moderators. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(7), 583–596. 10.1037/ccp0000514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogge RD, Cobb RJ, Lawrence E, Johnson MD, & Bradbury TN (2013). Is skills training necessary for the primary prevention of marital distress and dissolution? A 3-year experimental study of three interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(6), 949–961. 10.1037/a0034209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Carlson RG, Rhoades GK, Markman HJ, Ritchie LL, & Hawkins AJ (2020). Best Practices in Relationship Education Focused on Intimate Relationships. Family Relations, 69(3), 497–519. 10.1111/fare.12419 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JW, Bradford K, Higginbotham BJ, & Skogrand L (2016). Relationship Help-Seeking: A Review of the Efficacy and Reach. Marriage & Family Review, 52(8), 781–803. 10.1080/01494929.2016.1157559 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- VanLaningham J, Johnson DR, & Amato PR (2001). Marital Happiness, Marital Duration and the U-Shaped Curve: Evidence from a Five-Wave Panel Study. Social Forces, 79(4), 1313–1341. 10.1353/sof.2001.0055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, & Luo Y (2002). Marital quality and marital stability: Consequences for psychological well-being. Paper Presented at the Meetingsof the American Sociological Association, August. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford HA, Harris MG, McKeon G, Baxter A, Pennell C, Barendregt JJ, & Wang J (2013). Estimating remission from untreated major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 43(8), 1569–1585. 10.1017/S0033291712001717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.