Abstract

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) endow proteins with new properties to respond to environmental changes or growth needs. With the development of advanced proteomics techniques, hundreds of distinct types of PTMs have been observed in a wide range of proteins from bacteria, archaea, and eukarya. To identify the roles of these PTMs, scientists have applied various approaches. However, high dynamics, low stoichiometry, and crosstalk between PTMs make it almost impossible to obtain homogeneously modified proteins for characterization of the site-specific effect of individual PTM on target proteins. To solve this problem, the genetic code expansion (GCE) strategy has been introduced into the field of PTM studies. Instead of modifying proteins after translation, GCE incorporates modified amino acids into proteins during translation, thus generating site-specifically modified proteins at target positions. In this review, we summarize the development of GCE systems for orthogonal translation for site-specific installation of PTMs.

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

In the first class of biochemistry, it is taught that proteins are composed of a set of 20 amino acids. Two additional amino acids, selenocysteine and pyrrolysine, have also been found as components of a limited number of proteins in specific organisms.1–3 At the very beginning, they were thought as modifications of cysteine and lysine residues respectively, but later scientists found that both amino acids are linked to their cognate tRNAs and then delivered to ribosomes for protein synthesis, sharing a similar process of translation with the set of 20 canonical amino acids. In a more accurate way, these 22 amino acids together are named as proteinogenic amino acids. On the other hand, protein side chains usually undergo modifications during different growth stages or after stimuli in living cells. Since these modifications occur after translation, they are named as post-translational modifications (PTMs).4,5

The first protein PTM was discovered 90 years ago. Fritz Lipmann and Phoebus Levene detected phosphoserine in casein in 1933.6 Later, lysine acetylation in histones was discovered by Vincent Allfrey in 1964.7 During the past decade, PTM studies have encountered a new era with the development of advanced proteomics techniques that have identified more than 600 distinct types of PTMs in thousands of proteins covering almost all the biological processes in bacteria, archaea, and eukarya.8–10 PTMs can change charges of protein side chains such as phosphorylation and acetylation to affect substrate binding or interactions with other biomolecules.11–14 PTMs can also add specific tags to proteins for triggering corresponding biological processes such as ubiquitination and glycosylation.15–18 More importantly, PTMs have been found to be closely associated with a variety of human diseases including cancers,19 cardiovascular diseases,20 diabetes,21 neurodegenerative diseases,22 and even coronavirus diseases in the recent COVID-19 pandemic.23 Thus, protein PTMs have been attracting attentions of scientists from different research fields for decades.

There are several major challenges in PTM studies. First, the same type of PTM can occur at multiple sites in a single protein. Second, different types of PTMs can occur at the same residue in proteins. Third, PTMs at different sites have crosstalk between each other, no matter if they are the same or distinct types of PTMs. Fourth, PTMs are high dynamic processes between modified and unmodified forms. Thus, it is necessary to generate a protein with a homogeneous modification at the PTM site to demonstrate its site-specific effect on the target protein, and this is essential for downstream studies such as functional determination and drug development. To achieve this goal, classic approaches usually use PTM mimicking amino acids to replace PTMs at the target site by site-directed mutagenesis. For example, glutamate is commonly used as the substitution for a phosphorylated serine and threonine or even tyrosine residue,24 while glutamine is usually used as the mimic for an acetylated lysine residue.25 The advantages of this strategy include the following: First, it is easy to implement with commercially available kits; Second, these PTM mimicking amino acids are stable in cells, which is especially important for in vivo studies. However, the differences in sizes and charges of these PTM mimicking amino acids from those of native PTMs sometimes make them not sufficient substitutions.26,27 Thus, the most rigorous way is to produce proteins with native PTMs at target sites.

Due to high dynamics, low stoichiometry, and existence of multiple PTMs, it is almost impossible to isolate homogeneously modified proteins from living cells. Scientists have applied various biological and chemical approaches to overcome those challenges.28,29 First, specific modifying enzymes such as kinases and acetyltransferases can be used to modify proteins at target sites.30,31 However, this approach only has confined applications due to limited knowledge in substrate specificities of modifying enzymes. Second, solid-phase peptide synthesis can be implemented to generate site-specifically modified peptides,32,33 but this method only applies for proteins or peptides with short lengths. To overcome the length limit of solid-phase peptide synthesis, the native chemical ligation reaction has been established to link PTM-containing peptide fragments to form a full-length protein with PTMs at target sites.34,35 However, such semisynthetic approach sometimes needs refolding of proteins after purification. Furthermore, all these above-mentioned methods only apply to in vitro studies, leaving gaps in installing desired PTMs into target proteins in living cells.

To fill in this gap, the genetic code expansion (GCE) strategy has been applied for PTM studies.36–40 It introduces an orthogonal translation system (OTS) into living cells to genetically encode a noncanonical amino acid (ncAA) at a chosen site of target proteins.41–43 The OTS is mainly composed of an engineered aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (AARS), which recognizes the ncAA, and an engineered tRNA, which bears a specific anticodon to read an assigned codon in mRNA (Figure 1).44–46 The orthogonality of an OTS includes the following: First, the target ncAA cannot be recognized by host AARSs; Second, the engineered AARS cannot recognize canonical amino acids and cannot aminoacylate host tRNAs; Third, the engineered tRNA cannot be aminoacylated by host AARSs. To date, majority of established OTSs are derived from the pair of tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (TyrRS) and tRNATyr from Methanococcus jannaschii or Escherichia coli and the pair of pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase (PylRS) and tRNAPyl from Methanosarcina species.47,48 There are also a series of “not-so-popular” orthogonal pairs, expanding the diversity of ncAAs that can be genetically encoded in living cells.49 It should be noted that there are several potential problems when applying the GCE method. First, since the introduced OTS can decode the assigned codon (commonly a UAG stop codon) as an ncAA not only in the target mRNA but also in mRNAs of native genes in host cells, the GCE method could lead to off-target ncAA incorporation at more sites than the desired target in living cells. Moreover, due to the competition from release factors or near cognate tRNAs for the assigned stop codon, the GCE approach could generate truncated or mistranslated target proteins, correspondingly. To overcome these issues, several strategies have been applied such as optimizing OTS efficiencies, eliminating release factors, and engineering elongation factor-Tu (EF-Tu) or ribosomes.50

Figure 1.

The scheme for the GCE strategy. The noncanonical amino acid (ncAA) is specifically recognized by an engineered aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (AARS*) and attached to a cognate tRNA*. The pair of introduced AARS* and tRNA* is orthogonal in host cells and does not cross react with native pairs of AARS and tRNA in hosts. Then ncAA-charged tRNA* is delivered to the ribosome and reads an assigned codon in mRNA, allowing genetic encoding of an ncAA into the target protein at a controlled site.

Instead of modifying proteins post-translationally, the GCE method can install PTMs into proteins cotranslationally, producing proteins with homogeneous PTMs at target sites for further studies, especially for in vivo studies.51–53 In later sections of this review, we will describe common PTMs of individual amino acid in nature and summarize methods for site-specific installation of PTMs into proteins, focusing on the development of OTSs for genetically encoding various ncAAs into proteins as native PTMs, PTM analogs, or PTM precursors either in vitro or in vivo. We also discuss limitations of certain methods and propose future directions of OTS development for PTM studies.

2. ARGININE MODIFICATIONS

Arginine is a basic amino acid with a guanidinium group that has a pKa value of 13.8,54 making arginine residues positively charged under physiological conditions. The majority of arginine PTMs have been found in histones, including methylation and citrullination (deimination) of the guanidinium group.55,56 There are also some other arginine modifications such as phosphorylation and ADP-ribosylation.57,58 In this section, we summarize the development of OTSs for generating proteins with arginine methylation and citrullination.

2.1. Arginine Methylation

Arginine methylation has been found to regulate a wide range of biological processes, including DNA damage repair, transcription, splicing, cell signaling, and cell cycles.59–61 They are involved in many human diseases such as cancers and inflammatory-related diseases.62–64 Arginine methylation is catalyzed by protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs), which transfer the methyl group from S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) to the guanidinium group. To date, humans are known to have nine PRMTs, which are further categorized into three types according to their methylation products (Figure 2). Type I PRMTs generate monomethylarginine and can add another methyl group to the same nitrogen atom to form asymmetric N,N′-dimethyl-arginine. Type II PRMTs also generate monomethylarginine but can add a methyl group to another nitrogen atom in the guanidinium group to form symmetric N,N-dimethylarginine. Type III PRMTs only generate monomethylarginine.65,66 For the reverse reaction, it is still controversial whether specific protein arginine demethylases exist to remove methyl groups from methylated arginine residues or not.67

Figure 2.

Three types of PRMTs. All three types of PRMTs can generate monomethylarginine. Type I PRMTs can further form asymmetric N,N′-dimethyl-arginine, while Type II PRMTs produce symmetric N,N-dimethyl-arginine. Type III PRMTs only generate monomethylarginine. SAM: S-Adenosyl-l-methionine; SAH: S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine.

To study site-specific effects of arginine methylation on protein function and structure, two chemical approaches have been developed to install methylated arginine or analogs into recombinant proteins in vitro. Both methods need to first apply site-directed mutagenesis to replace the target arginine residue with cysteine. The first reaction is based on cysteine alkylation with α,β-unsaturated amidine scaffold harboring different degrees of methylation (Figure 3A).68 Such methylarginine analogs have two variations from methylarginine: γ-methylene is replaced with a sulfur atom, and the secondary amine is substituted by ε-methylene. To install native methylarginine, C(sp3)–C(sp3) bond formation through carbon free radicals has been adopted (Figure 3B).69 The mutated cysteine residue fist undergoes elimination to form dehydroalanine (Dha) and then reacts with methylarginine-containing free radicals generated from alkyl halides via homolytic bond division in the presence of NaBH4.

Figure 3.

Chemical approaches to installing arginine methylation or analogs into proteins in vitro. A) The mutated cysteine residue is alkylated with α,β-unsaturated amidine scaffold harboring different degrees of methylation. Monomethylarginine analog: R1 = H, R2 = CH3, R3 = H; Asymmetric N,N′-dimethyl-arginine analog: R1 = H, R2 = CH3, R3 = CH3; Symmetric N,N-dimethyl-arginine analog: R1 = CH3, R2 = CH3, R3 = H. B) The mutated cysteine residue undergoes elimination to form dehydroalanine and then reacts with methylarginine-containing free radicals generated from alkyl halides in NaBH4. Monomethylarginine: R1 = CH3 R2 = H; Asymmetric N,N′-dimethyl-arginine: R1 = CH3, R2 = CH3.

To date, no OTS has been developed to incorporate methylarginine site-specifically into proteins in vivo. However, one study used the GCE strategy with cell-free translation systems to incorporate methylarginine into proteins, providing bases for further developing OTSs for genetic encoding methylarginine.70 In this work, monomethylarginine was first linked to a mutant yeast tRNAArg harboring a four-base anticodon CCCG by yeast arginyl-tRNA synthetase (ArgRS) through in vitro aminoacylation. Then methylarginine-charged tRNAArgCCCG was isolated and added into the cell-free translation system to decode the mutated CGGG codon at the target position of mRNA as methylarginine (Figure 4). This approach was only applicable for monomethylarginine but not for dimethyl-arginine, as it was shown that ArgRS cannot aminoacylate tRNAArg with neither asymmetric N,N′-dimethylarginine nor symmetric N,N-dimethyl-arginine.70 Another potential problem with this approach is that the cell-free translation system also produces arginine-charged tRNAArgCCG, which can compete with methylarginine-charged tRNAArgCCCG for the first three-base codon (CGG) in the CGGG four-base codon, thus forming a distinct read frame after the four-base codon. Indeed, truncated protein fragments were detected in this work due to a downstream stop codon if the CGGG codon is decoded as CGG.70 This problem could be solved by removing tRNAArgCCG in the cell-free translation system by biotin-tagged antisense DNA oligos and replacing all CGG codons in the mRNA with other Arg codons. Such a strategy has been used for other ncAA incorporation by cell-free translation systems.71

Figure 4.

The cell-free translation approach to incorporating monomethylarginine site-specifically into proteins. Yeast arginyl-tRNA synthetase (ArgRS) aminoacylates a mutant yeast tRNAArg bearing a four-base anticodon CCCG with monomethylarginine by in vitro aminoacylation. Then methylarginine-charged tRNAArgCCCG is added into the cell-free translation system to read an assigned CGGG codon in the mRNA as monomethylarginine to install arginine methylation at the target site.

2.2. Citrullination

Citrullination, or peptidyl arginine deimination, is a PTM of converting an arginine residue to a citrulline residue in proteins (Figure 5A). As the guanidinium group is hydrolyzed to become a ureido group, the arginine side chain losses its positive charge. The guanidinium group also losses two hydrogen-bond donors but obtains two hydrogen-bond acceptor sites.72 Protein citrullination regulates a variety of cellular processes, including gene expression, cell signaling, metabolism, and apoptosis.73,74 It is associated with a variety of human diseases, including cancers,75 inflammatory and autoimmune disorders,76 cardiovascular diseases,77 and neurodegeneration diseases.78 Citrullination is catalyzed by peptidyl arginine deiminases (PADs).79 There are 5 annotated PADs in the human genome (PAD1–4 and PAD6).80,81 So far, citrullination is still considered to be an irreversible PTM without known citrulline erasers, despite the existence of argininosuccinate synthetase and argininosuccinate lyase, which work together to convert free citrulline to arginine in the urea cycle.82–84

Figure 5.

Protein citrullination. A) The guanidinium group of the arginine residue is hydrolyzed by peptidyl arginine deiminases (PADs) to form a citrulline residue. B) The structures of citrulline and its mimicking amino acid, glutamine.

To study protein citrullination, glutamine has been used as a citrulline-mimicking amino acid.85 Glutamine has a carboxamide moiety that has similar numbers of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors to those in the ureido group, so it is considered as a feasible mimic of citrulline. However, the side chain of citrulline is ~2.7 Å longer than that of glutamine, making glutamine not an accurate substitution of citrulline (Figure 5B). To install native citrullination, the similar Dha-mediated approach to installing arginine methylation has been applied in vitro (Figure 3B).69 Instead, a citrulline moiety-containing free radical is generated from a corresponding alkyl halide in the presence of NaBH4 by homolytic bond fission and then reacts with Dha to form a C–C bond, thus changing the mutated cysteine residue to a citrulline residue.

Similar to installing arginine methylation (Figure 4), the cell-free translation system was also used to incorporate citrulline at the original arginine site by the GCE strategy.70 Yeast ArgRS charges tRNAArgCCCG with citrulline to form citullinyl-tRNAArgCCCG by in vitro aminoacylation that is then isolated and added into the cell-free translation system to decode the four-base codon CGGG in mRNA as citrulline. The fact that wild-type ArgRS can also recognize citrulline indicates the difficulty in engineering ArgRS to recognize citrulline but not arginine, making direct incorporation of citrulline challenging in vivo. Recently, an alternative strategy has been developed to overcome this challenge.86 Instead of citrulline, photocaged citrulline is first genetically encoded into proteins in mammalian cells. To develop an OTS that can incorporate o-nitrobenzyl photocaged citrulline, both the archaeal PylRS/tRNAPyl pair and the E. coli leucyl-tRNA synthetase (EcLeuRS)/tRNALeuCUA pair were selected for further engineering, because both pairs are known to be orthogonal in mammalian cells and can recognize ncAAs with long and bulky side chains.48,87 A selection based on GFP fluorescence was implemented and obtained an EcLeuRS variant (T252A, M40I, Y499I, Y527A, and H529G) that can incorporate photocaged citrulline site-specifically into proteins. After genetic encoding of photocaged citrulline into target proteins in living cells, the caging group can be removed by UV irradiation (365 nm), leaving native citrulline at the target position for downstream studies (Figure 6). By using this approach, it was shown that autocitrullination of R372 and R374 in protein arginine deiminase 4 deceases the enzyme activity by 181- and 9-fold, respectively.

Figure 6.

Site-specific incorporation of citrulline into proteins in mammalian cells. o-Nitrobenzyl photocaged citrulline is first genetically encoded in the target protein by an orthogonal pair of E. coli LeuRS (EcLeuRS) variant and tRNALeuCUA at an assigned position with a UAG stop codon. Then the caging group is removed by UV 365 nm exposure, and citrulline is formed at the desired site in the target protein.

3. ASPARAGINE MODIFICATIONS

Asparagine is a polar amino acid with a carboxamide group that has two hydrogen bond donors and two hydrogen bond acceptor sites. Asparagine residues have several types of PTMs such as hydroxylation to regulate gene transcription and signaling networks,88,89 spontaneous deamidation as a molecular marker for protein degradation,90,91 and methylation to mitigate protein damages from deamidation.92 A unique PTM for asparagine is N-glycosylation, though recent studies have found that arginine residues of few proteins in hosts are targets of N-glycosylation catalyzed by bacterial effector proteins for host–pathogen interactions.93 In this section, we focus on the development of OTSs for generating proteins with N-glycosylation analogs.

3.1. N-Glycosylation

N-Glycosylation can be found in about half of all eukaryotic proteins94 and affects protein structure, stability, solubility, folding, and quality control.95 It plays important roles in protein trafficking and cell signaling.96 N-Glycosylation is catalyzed by oligosaccharyl transferase that transfers oligosaccharide from a lipid-linked donor to the asparagine residue in a Asn-Xaa-Ser/Thr consensus sequence.97,98

Most challenges in glycosylation studies result from its high heterogeneity with varied numbers of saccharides, types of saccharides, and linkage between saccharides. To overcome these challenges, scientists have made remarkable progresses to generate glycoproteins with homogeneous saccharides through native chemical ligation, chemo-selective ligation, and enzymatic catalysis and remodeling.99–101 Take a chemical approach based on S-alkylation as an example: the target asparagine residue is first mutated to cysteine, which reacts with glycosyl-β-N-iodoacetamide to form a sulfur-containing analog of N-glycosylation in vitro (Figure 7).102

Figure 7.

A chem-selective ligation approach to generating N-glycosylation analogs. The target asparagine residue is first mutated to cysteine, which is then reacted with glycosyl-β-N-iodoacetamide by S-alkylation to form a sulfur-containing analog of N-glycosylation in vitro.

The direct incorporation of glycosylated asparagine into proteins by GCE has been challenging for decades due to the difficulty in engineering AARS binding pockets to accommodate large-sized glycans. Alternatively, several semisynthetic approaches combining GCE and chemical ligation have been developed. In an earlier study, an aspartate derived thioester was first genetically encoded into proteins by an Methanosarcina barkeri PylRS (MbPylRS) variant (A267Y, Y271A, N311T, C313G, and Y349F) in E. coli cells. After aspartate thioester-containing recombinant proteins were purified, the thioester moiety was linked to a cysteine-glycan conjugate by transthioesterification, followed by an S- to N-acyl transfer to form a cysteine-bridged N-glycosylation analog in vitro (Figure 8A).103 The advantage of this approach is that the free thiol group in the cysteine bridge can be further used as a handle to add tags to the target protein for purification, detection, and functional characterization. In a later study, aspartate β-benzyl ester was first genetically encoded into target proteins by another MbPylRS variant (N311C, C313S, and Y349F) in E. coli cells. After the target proteins were purified, the ester moiety was hydrazinolyzed to form alanine-β-hydrazide, followed by ligation with reducing carbohydrate in vitro (Figure 8B).104 By this approach, a variety of carbohydrates can be linked to target proteins such as N-acetylated monosaccharides, disaccharides, trisaccharide, and tetrasaccharide analogs. More importantly, the product is a close mimic of native N-glycosylation, facilitating further generation of complex glycans through enzymatic catalysis and remodeling.

Figure 8.

Semisynthetic approaches to installing N-glycosylation analogs into proteins. A) An aspartate derived thioester is first incorporated into proteins by GCE and then linked to a cysteine-glycan conjugate by transthioesterification in vitro, followed by an S- to N-acyl transfer to form a cysteine-bridged N-glycosylation analog. B) Aspartate β-benzyl ester is first encoded into proteins by GCE and then hydrazinolyzed to form alanine-β-hydrazide in vitro, followed by ligation with reducing carbohydrate.

4. CYSTEINE MODIFICATIONS

Cysteine is a polar amino acid bearing a thiol group with a pKa value of 8.3, making cysteine residues usually involved in enzymatic reactions as nucleophiles. Disulfide bonds between cysteine residues are essential for protein folding and stability.105,106 Common PTMs of cysteine residues include oxidation for redox signaling pathways,107 methylation for membrane protein functions,108 S-nitrosylation for protein localization,109 and lipidation for cell signaling.110 In this section, we focus on the development of OTSs for generating proteins with analogs of S-palmitoylation, which is one type of protein lipidation unique to cysteine residues.

4.1. S-Palmitoylation

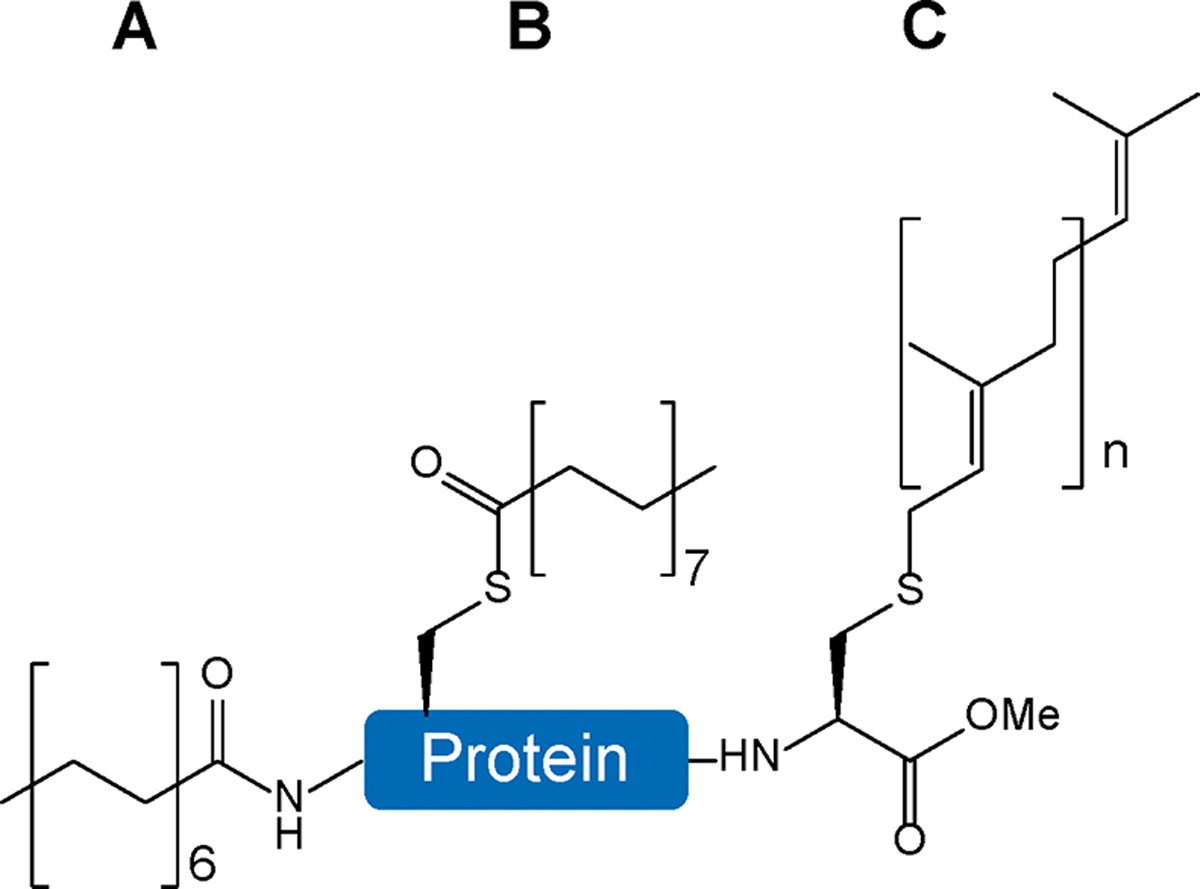

Protein lipidation is to link long-chain fatty acids to proteins, regulating membrane protein localization, trafficking, and interactions with other biomolecules.111 Abnormalities of protein lipidation have been shown to be associated with human diseases such as metabolic disorders, neurological diseases, and cancers.112–114 Common types of protein lipidation include N-myristoylation, S-prenylation, and S-palmitoylation, while C-phosphatidylethanolaminylation and N-palmitoylation are rare (Figure 9).115 Among them, S-palmitoylation is the only reversible modification, while others are irreversible and commonly linked to termini of proteins. S-Palmitoylation adds palmitate to cysteine residues by protein S-acyltransferases that contain a cysteine-rich domain with a consensus Asp-His-His-Cys (DHHC) motif.116

Figure 9.

Common types of protein lipidation. A) N-Myristoylation is an irreversible modification linked to the N-termini of proteins. B) S-Palmitoylation is a reversible modification attached to internal cysteine residues. C) S-Prenylation is an irreversible modification linked to cysteine residues at C-termini of proteins (n = 2: farnesylation; n = 3: geranylgeranylation).

To study protein lipidation, classic chemical approaches such as solid-phase peptide synthesis and native chemical ligation have been used to generate proteins with lipid moieties.113 Semisynthetic methods combining GCE and chemical ligation have also been developed. In an earlier study, p-ethynylphenylalanine, an alkyne group-containing phenylalanine analog, was first genetically encoded into proteins by a yeast phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase (ScPheRS) variant (T415A) in E. coli cells. After protein purification, it was linked to palmitic acid-azide by copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition to form an S-palmitoylation mimic in vitro (Figure 10A).117 In a later study, p-azido-phenylalanine (pAzF), an azide-containing phenylalanine analog, was first site-specifically incorporated into proteins by an engineered M. jannaschii TyrRS (MjTyrRS) variant (Y34T, E107N, D158P, I159L, and L162Q) in E. coli cells. Then the pAzF-containing protein was purified and reacted with dibenzocyclooctyne group-containing palmitic acid by strain-promoted azide–alkyne cycloaddition in vitro (Figure 10B).118

Figure 10.

Semisynthetic approaches by GCE and chemical ligation to installing S-palmitoylation mimics into proteins. A) p-Ethynylphenylalanine is first site-specifically incorporated into proteins and then linked to 15-azido-pentadecanoic acid by copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition in vitro. B) p-Azido-phenylalanine is first genetically encoded into proteins and then reacts with dibenzocyclooctyne-palmitic acid conjugate by strain-promoted azide–alkyne cycloaddition in vitro.

Both above-mentioned ncAA-mediated semisynthetic methods only apply to in vitro studies. The long length of fatty acids makes it impossible to engineer AARSs for direct incorporation of S-palmitoylation in living cells. Recently, an alternative approach based on GCE has been developed to generate proteins with an S-palmitoylation mimic in mammalian cells.119 In this work, a carbon–carbon triple bond containing compound, bicyclo[6.1.0]nonyne-lysine, was first genetically encoded into proteins by an Methanosarcina mazei PylRS (MmPylRS) variant (Y306A and Y384F) in mammalian cells and reacted with tetrazine-containing palmitic acid derivatives by the biocompatible inverse-electron-demand Diels–Alder reaction to form S-palmitoylation mimics in living cells (Figure 11). This work also demonstrated that such S-palmitoylation mimics can activate downstream signaling transduction, demonstrating promising applications in protein lipidation studies in vivo.120

Figure 11.

Site-specific incorporation of S-palmitoylation mimics into proteins in mammalian cells. Bicyclo[6.1.0]nonyne-lysine is first genetically encoded into proteins by an orthogonal pair of engineered PylRS/tRNAPyl at an assigned position with a UAG stop codon and then reacts with a tetrazine-containing palmitic acid analog by the inverse-electron-demand Diels–Alder reaction to form an S-palmitoylation mimic in living cells.

5. GLUTAMINE MODIFICATIONS

Glutamine is another carboxamide-containing amino acid. Glutamine residues also undergo spontaneous deamidation, which triggers protein aggregation,121,122 and methylation, which regulates transcription,123 translation,124 and methanogenesis.125 In this section, we focus on the development of OTSs for generating proteins with glutamine methylation.

5.1. Glutamine Methylation

Glutamine methylation is relatively rare compared to lysine methylation and arginine methylation. To date, only a few proteins have been identified as glutamine methylation targets, including release factors,124,126 ribosomal proteins,127 histones,123 and methanogenic enzymes.125 Glutamine methylation is catalyzed by glutamine methyltransferases, which are also SAM-dependent enzymes like arginine methyltransferase.125 Interestingly, the enzyme HEMK2-TRMT112 catalyzes methylation of both lysine residues in histones and glutamine residues in release factors.128 Recently, an ncAA-mediated approach has been developed to generate proteins with glutamine methylation.129 First, L-glutamic acid γ-benzyl ester is site-specifically incorporated into proteins by an MbPylRS variant (N311S, C313A, and Y349F) in E. coli cells. After protein purification, it is converted into acyl hydrazide, followed by a reaction with acetyl acetone to form a Knorr pyrazole at pH 3. Finally, methylamine is added into the mixture with adjusted pH 9 to generate proteins with native glutamine methylation at the target position in vitro (Figure 12). To date, there is no established OTS to site-specifically incorporate methylated glutamine into proteins in living cells, which will be the next milestone in the field of glutamine methylation.

Figure 12.

An ncAA-mediated approach to installing glutamine methylation into target proteins. L-Glutamic acid γ-benzyl ester is first site-specifically incorporated into proteins by GCE, then it is converted to glutamyl hydrazide in vitro, followed by a reaction with acetyl acetone to form a Knorr pyrazole intermediate. In the last step, methylamine is added to generate proteins with glutamine methylation at the target position.

6. HISTIDINE MODIFICATIONS

Histidine is a basic amino acid with an imidazole group. The pKa value of imidazole in water is about 6, but protein local environments can change the pKa value of imidazole, making histidine residues wobble between positive and neutral under physiology conditions. Histidine residues are involved in catalytic mechanisms of many enzymes such as proteases. PTMs of histidine residues include phosphorylation involved in cellular signal transduction,130,131 hydroxylation found in ribosomal proteins,132,133 oxidation associated with redox sensing,134 and methylation related to regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics and protein translation.135,136 In this section, we focus on the development of OTSs for generating proteins with histidine methylation.

6.1. Histidine Methylation

Histidine methylation is an emerging field, even though it was first discovered in actin in 1967.137,138 A recent study has identified 299 histidine methylation sites in 254 human proteins, which is less abundant compared to 788 lysine methylation sites in 584 human proteins and 1154 arginine methylation sites in 764 human proteins.139 Histidine methylation is catalyzed by protein histidine methyltransferases (PHMTs), which are also SAM-dependent enzymes (Figure 13).136 Only three proteins have been assigned as PHMTs in humans to date. SETD3 and METTL18 can generate 3-methyl-histidine,140,141 while METTL9 produces 1-methyl-histidine.142

Figure 13.

Histidine methylation by protein histidine methyltransferases (PHMTs). There are two kinds of PHMTs depending on the methylation site in the imidazole group. In humans, SETD3 and METTL18 generate 3-methyl-histidine, while METTL9 produces 1-methyl-histidine. SAM: S-adenosyl-l-methionine. SAH: S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine.

Before human PHMTs were identified, an earlier study has already applied GCE to genetically encode 3-methyl-histidine and other histidine analogs in both E. coli and mammalian cells.143 PylRS was engineered to recognize histidine analogs because of its high plasticity for amino acid recognition.144 An MbPylRS variant (L270I, Y271F, L274G, C313F, and Y349F) was obtained after selection for 3-methyl-histidine specifically. In this work, 3-methyl-histidine was site-specifically incorporated into a fluorescent protein and changed its spectral properties. Now, with the knowledge in PHMTs, it is promising to generate proteins with naturally existing histidine methylation to study their biological functions.

7. LYSINE MODIFICATIONS

Lysine is another basic amino acid with an amine group at the ε-end. The pKa value of the ε-amine group is 10.8, making lysine residues bring positive charges under most physiological conditions. Lysine is one of the most frequent PTM-targeting amino acids. About 30 distinct types of lysine PTMs have been identified in eukaryotic and bacterial cells.145 The most abundant lysine PTMs include ubiquitination, acetylation, SUMOylation, succinylation, crotonylation, methylation, malonylation, and 2-hydroxy-isobutyrylation. In this section, we summarize the development of OTSs to generate proteins with lysine PTMs and their analogs.

7.1. Lysine Acetylation

Lysine acetylation was first discovered in histones in 1964.7 During many years after its discovery, studies on lysine acetylation have focused on its regulatory roles in transcription.146,147 With the development of advanced proteomics techniques, now it is known that lysine acetylation is not only existing in histones but also in nonhistone proteins.148,149 Moreover, lysine acetylation is not unique for eukaryotic cells but also occurs in bacterial cells.150–152 The biological processes in which lysine acetylation plays roles range from gene expression to cell singling and metabolism.13,153 Lysine acetylation is involved in various human diseases including cancers,154 neurodegenerative diseases,155 kidney diseases,156 and bacterial infections.157 Lysine acetylation is catalyzed by protein acetyltransferases, which have 5 major families: the Gcn5-related N-acetyltransferase family, the CBP/p300 coactivators, the TAFII group of transcription factors, the MYST family, and the SRC family of coactivators.158 Lysine acetylation is a reversible PTM, and the removal of Nε-acetyl amide moieties is catalyzed by lysine deacetylases, which can be divided into two main families: hydrolytic deacetylases and NAD+-dependent deacetylases (sirtuins).159

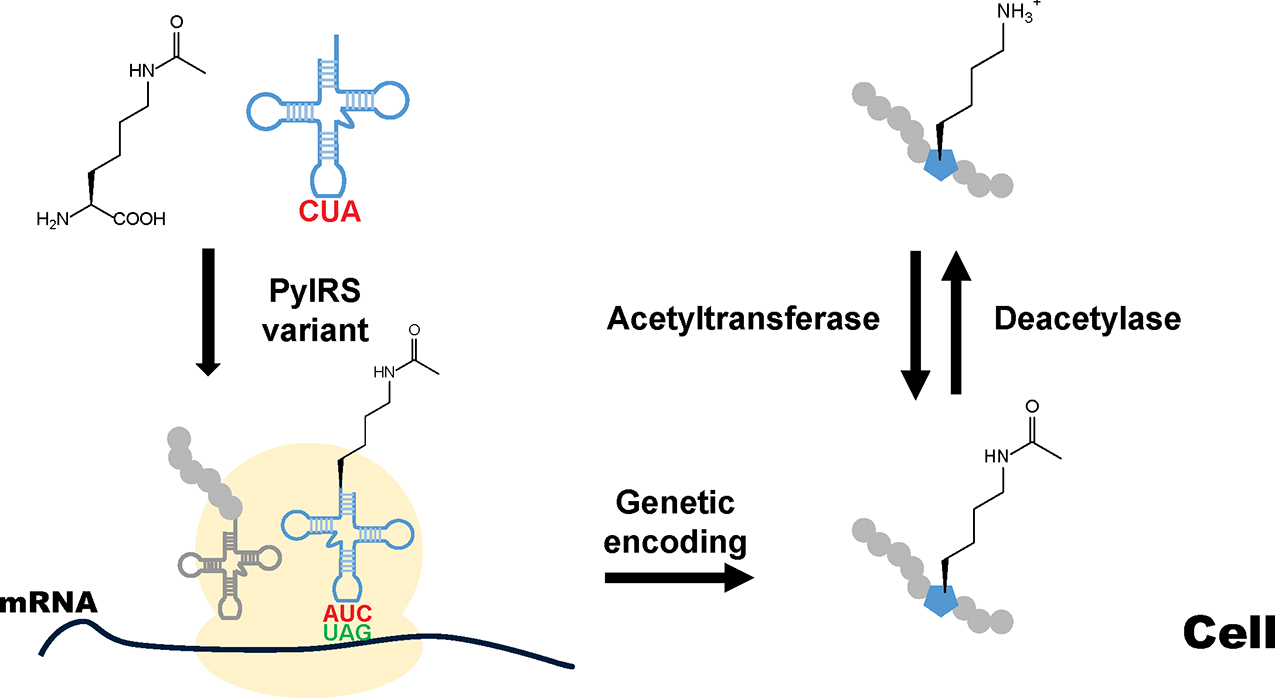

To study the functions of lysine acetylation, OTSs for direct incorporation of acetyllysine into target proteins in living cells have been developed (Figure 14). The first OTS for acetyllysine incorporation was established in E. coli cells and was derived from the pair of MbPylRS and tRNAPyl.160 The residues (Leu266, Leu270, Tyr271, Leu274, Cys313, and Trp383) around the binding pocket of pyrrolysine were randomized for selections, and two variants recognizing acetyllysine were obtained, MbAcKRS-1 (D76G, L266 V, L270I, Y271F, L274A, and C313F) and MbAcKRS-2 (L270I, Y271L, L274A, and C313F). By further engineering MbAcKRS-1, a better MbAcKRS-3 (D76G, L266M, L270I, Y271F, L274A, and C313F) was shown to improve acetyllysine incorporation.161 Later, another OTS for acetyllysine was developed based on MmPylRS.162 Two MmPylRS variants, MmAcKRS-1 (L301M, Y306L, L309A, and C348F) and MmAcKRS-2 (L301M, Y306L, and C348S), were demonstrated to have higher acetyllysine incorporation efficiency. However, even with those optimized AcK-OTSs, the suppression of stop codons by acetyllysine-charged tRNAPyl is still relatively low compared to OTSs for other ncAAs. To further increase acetyllysine incorporation efficiency, several approaches to engineering components in AcK-OTSs have been implemented. First, because tRNAPyl is originally from methanogenic archaea, its binding to host EF-Tu is not optimal. Thus, the interacting nucleotides of tRNAPyl with EF-Tu, C6-G67:C7-G66, were mutated to C6-G67:G7-C66 for higher binding affinity.163 Second, due to the size limit of mutant libraries, earlier studies only randomized residues around the amino acid binding pocket, while residues in other parts of the enzyme could also benefit the incorporation. To overcome this challenge, phage-assisted continuous evolution (PACE) was performed for the full-length chimeric PylRS (chPylRS, the chimera of residues 1–149 of MbPylRS and residues 185–454 of MmPylRS).164 Indeed, several mutations at other parts of chPylRS (V31I, T56P, H62Y, and A100E) further enhanced acetyllysine incorporation. Third, the stop codon is commonly used for ncAA incorporation, while release factors can compete with ncAA-charged tRNAs for those assigned stop codons, thus decreasing ncAA incorporation efficiencies. To solve this problem, the C-terminal domain of ribosomal protein L11 was overexpressed to decrease release factor-mediated termination, showing the ability to incorporate acetyllysine at three distinct sites in a single protein.165 Furthermore, because of the orthogonality of PylRS-derived OTSs in both bacteria and eukaryotes, genetic encoding of acetyllysine into proteins has been established in different organisms, including E. coli,160,162 Salmonella,166 yeast,167,168 mammalian cells,169,170 stem cells,171 and animals.172 The applications of these AcK-OTSs in determining the roles of lysine acetylation in regulating specific proteins, from histones to nonhistone proteins, have been nicely reviewed recently.36,38,40,173

Figure 14.

Direct installation of lysine acetylation into proteins in living cells by GCE. Nε-Acetyllysine is genetically encoded into the target protein by an engineered PylRS variant and tRNAPyl at a designed position with a UAG stop codon in living cells. The acetylation of lysine residues is a reversible process, regulated by acetyltransferases and deacetylases.

There is one potential problem when using AcK-OTSs for in vivo studies. Due to existence of deacetylases, site-specifically incorporated acetyllysine residues by GCE undergo deacetylation, especially in yeast or mammalian cells, and the stoichiometry of acetylation at target sites varies from batch to batch to make inconsistence among replicates. Thus, it is necessary to use nondeacetylatable analogs of acetyllysine, especially when long-time observation is needed for in vivo studies. Several lysine derivatives can be used for this purpose (Figure 15). First, 2-amino-8-oxononanoicacid (KetoK) has the same length of side chains as acetyllysine but replaces the nitrogen atom with carbon, so it cannot be hydrolyzed. The site-specific incorporation of KetoK into proteins has been established using MbAcKRS-1 in E. coli cells.174 Second, thioacetyllysine (TAcK) replaces the oxygen atom with sulfur, and TAcK-containing small peptides have been shown to inhibit sirtuin deacetylases.175 The OTS for TAcK has been developed by further engineering MbAcKRS-1 with two additional mutations (F271L and F313C).176 In this work, TAcK-containing proteins were shown to be recognized by acetyllysine-antibodies and had similar enzyme activities to acetyllysine-containing proteins. Moreover, TAcK-containing proteins were shown to resist CobB, the sirtuin deacetylase in E. coli. All these facts indicate TAcK is an ideal non-deacetylatable mimic of acetyllysine for in vivo studies. Later, trifluoro-acetyllysine (TFAcK) was genetically encoded into proteins by an MbPylRS variant (L266M, L270I, L274A, and C313F) as a probe to detect protein conformational changes by 19F NMR.177 In this study, TFAcK-containing proteins were also demonstrated to be resistant to sirtuin deacetylases. Recently, another stable mimic of acetyllysine, 1,2,4-triazole amino acid (ApmTri), has been site-specifically incorporated into proteins by WT MmPylRS in mammalian cells.178 The ApmTri-containing proteins were shown to have similar binding affinity with other proteins to that of acetyllysine-containing proteins. All these above-mentioned acetyllysine mimics offer alternative approaches when acetyllysine residues undergo rapid deacetylation in living cells.

Figure 15.

Acetyllysine and its nondeacetylatable analogs. AcK: acetyllysine; KetoK: 2-amino-8-oxononanoicacid; TAcK: thio-acetyllysine; TFAcK: trifluoro-acetyllysine; ApmTri: 1,2,4-triazole amino acid.

7.2. Lysine Methylation

Lysine methylation was first discovered in a bacterial flagellar protein in 1959, earlier than its discovery in histones.179 Besides its key role in regulating gene expression, lysine methylation of nonhistone proteins is also involved in a wide range of biological processes such as DNA damage repair, cellular signaling, metabolism, cell cycle, and cell differentiation.180–182 Abnormalities of lysine methylation has been found in patients of cancers,183,184 nervous system diseases,185,186 diabetes,187 cardiovascular diseases,188 and developmental disorders.189 Methylation of lysine residues is catalyzed by protein lysine methyltransferases (PKMTs). Humans have more than 60 PKMTs, which can be mainly classified as SET-domain-containing PKMTs and non-SET domain PKMTs.190,191 The reverse process, demethylation, is catalyzed by protein lysine demethylases (KDMs) through two distinct mechanisms: aminooxidation or hydroxylation.192 Different from methylation of arginine, glutamine, and histidine residues, lysine methylation has three degrees (mono-, di-, and trimethylation), and its regulatory role depends on methylation degrees.182,193 Another important feature of lysine methylation is that it keeps positive charges of lysine residues under physiological conditions, which is distinct from other lysine PTMs.

To generate proteins with degree- and site-specific lysine methylation, several semisynthetic approaches have been developed (Figure 16). Sulfur-containing lysine methylation mimics can be generated by alkylation chemistry of cysteine residues in vitro.194 Sulfur-containing analogs of lysine methylation can also be obtained by Michael addition reactions of Dha tags with thiol-containing compounds.195,196 It should be noted that those thioether bonds are sensitive to oxidation. To generate proteins with native lysine methylation, C–C bond formation reactions by free radical chemistry69 or single-electron transfer197 have been adopted. However, proteins generated by these approaches lose native stereo-chemistry at target lysine residues.

Figure 16.

Semisynthetic approaches to generating proteins with lysine methylation with different degrees. The target lysine residue is first mutated to cysteine. A) Alkylation of the cysteine residue forms sulfur-containing lysine methylation mimics. Then cysteine can be eliminated to form dehydroalanine (Dha). B) Michael addition of Dha produces sulfur-containing lysine methylation mimics. C) The Free radical reaction or D) single-electron transfer by Bpin (alkylboronic acid pinacol ester) with Dha forms C–C bond to generate proteins with native lysine methylation. Monomethylation: R1 = CH3, R2 = H, R3 = H; dimethylation: R1 = CH3, R2 = CH3, R3 = H; trimethylation: R1 = CH3, R2 = CH3, R3 = CH3.

Direct installation of lysine methylation into proteins in vivo has not been established by GCE yet, largely due to the high structural similarity between methylated lysine and unmodified lysine. However, several approaches based on ncAA-mediated chemical or physical reactions have been developed to install lysine methylation with different degrees. Monomethylation can be achieved by acid treatment of tert-butyloxycarbonyl-methyllysine incorporated by OTSs with WT MbPylRS or an MmPylRS variant (Y384F),198,199 Ru-mediated elimination of allylcarbamoyl-methyllysine encoded by the OTS with an MbPylRS variant (Y349F),200 reductive decaging of p-nitrobenzyloxycarbonyl-methyllysine installed by the OTS with an MbPylRS variant (Y271G and C313 V),201 and UV decaging of o-nitrobenzylcarbamoyl-methyllysine encoded by OTSs with an MbPylRS variant (Y271I, L274M, and C313A) or an MmPylRS variant (Y306M, L309A, and C348T) (Figure 17).202,203 More importantly, the approach by UV decaging was demonstrated to generate proteins with monomethyllysine in mammalian cells, providing a powerful tool for in vivo studies on lysine methylation.202

Figure 17.

The generation of monomethyllysine-containing proteins by ncAA-mediated approaches. A) 2% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) treatment of tert-butyloxycarbonyl-methyllysine. B) Chloro-pentamethylcyclopentadienyl-cyclooctadiene-ruthenium(II) ([Cp*Ru(cod)Cl])-catalyzed cleavage of allylcarbamoyl-methyllysine. C) Reductive decaging of p-nitrobenzyloxycarbonyl-methyllysine. D) UV decaging of o-nitrobenzylcarbamoyl-methyllysine in living cells.

For dimethylation, two ncAA-mediated approaches have been established in vitro (Figure 18). In the earlier work, tert-butyloxycarbonyl (Boc)-lysine was first site-specifically incorporated into proteins by WT MbPylRS in E. coli cells. After purification, other free lysine residues in the protein were protected by the benzyloxycarbonyl (Cbz) group. Next, the Boc group was removed by trifluoroacetic acid, followed by the installation of dimethylation by reductive alkylation with formaldehyde and a dimethylamine borane complex. Finally, Cbz-protected lysine residues were deprotected by trifluoromethanesulfonic acid, trifluoroacetic acid, and dimethylsulfide mixtures.204 Later, an easier method was developed.205 Nε-(4-azidobenzoxycarbonyl)-δ,ε-dehydrolysine was genetically encoded into proteins by an MmPylRS variant (L309T, C348G, and Y384F) in E. coli cells. Then proteins were purified, and the precursor residue was reduced to allysine by Staudinger reduction with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, followed by conversion to dimethyllysine by reductive amination with dimethylamine in the presence of NaCNBH3.

Figure 18.

The generation of dimethyllysine-containing proteins by ncAA-mediated approaches. A) tert-Butyloxycarbonyl (Boc)-lysine is first genetically encoded into proteins at the target site 1, and all free lysine residues at other positions 2 are protected with benzyloxycarbonyl (Cbz) group by benzyloxycarbonyloxy-succinimide (Cbz-OSu). Then the Boc-protected lysine residue is deprotected by trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and methylated by reductive alkylation using formaldehyde and a dimethylamine borane complex. Finally, Cbz groups at other lysine resides are removed by a mixture of trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (TFMSA)/trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/dimethylsulfide (DMS). B) Nε-(4-azidobenzoxycarbonyl)-δ,ε-dehydrolysine is first site-specifically incorporated into proteins by GCE, followed by Staudinger reduction with tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) to form allysine and reductive amination with dimethylamine in the presence of NaCNBH3.

For trimethylation, instead of being derived from cysteine residues, two ncAAs were used to generate Dha tags, followed by Michael addition or metal-catalyzed C–C bond formation (Figure 19).206,207 Moreover, both methods can generate target proteins with lysine methylation at all three degrees. In the earlier study, phenylselenocysteine (PhSeCys) was first genetically encoded into proteins by the OTS with an MjTyrRS variant (Y32W, L65H, H70G, F108N, Q109S, D158S, and L162E). Then PhSeCys was converted to Dha with H2O2, followed by Michael addition with corresponding thiols to form sulfur-containing methyllysine mimics.206 In the later work, phosphoserine was first site-specifically incorporated into proteins by the OTS for phosphoserine (discussed in section 9.1) and converted to Dha under mild alkali conditions, followed by metal-mediated C–C bond formation with corresponding iodides to form native methyllysine modifications.207 Both methods can only be implemented in vitro, so the next breakthrough in this field is to develop methods to generate di- and trimethyllysine-containing proteins by cell-friendly and bio-orthogonal reactions.

Figure 19.

The generation of trimethyllysine-containing proteins by ncAA-mediated approaches. A) The dehydroalanine (Dha) tag is first formed by oxidation of genetically encoded phenylselenocysteine and then reacted with trimethylamine-containing thoil to form a mimic of trimethyllysine. B) The incorporated phosphoserine residue is converted to Dha by mild alkali treatment, followed by a metal-mediated coupling reaction with trimethylamine-containing iodide.

7.3. Lysine Acylation

Besides acetylation, lysine residues also undergo various types of acylation that have been recently identified by a series of proteomics studies.208 Among them, succinylation, crotonylation, malonylation, and 2-hydroxy-isobutyrylation have higher abundance than other types of acylation such as formylation and propionylation.145 Although the function, mechanism, and regulation of lysine acylation have not been as well studied as lysine acetylation, it is known that they are distributed as widely as lysine acetylation, from histones to nonhistone proteins and from eukaryotes to prokayotes.209 They are playing important roles in gene expression, cell signaling, and metabolism, and are involved in many human diseases.210 Here, we summarize established OTSs for genetically encoding lysine acylation or analogs in vivo (Figure 20).

Figure 20.

Genetically encoded acylated lysine or analogs. A) Nonpolar groups; B) polar groups; C) charged groups; D) other acylation; E) acylation analogs.

7.3.1. Nonpolar Acyl Groups.

Lysine propionylation has been found in histones and a number of bacterial proteins.211–213 The direct incorporation of propionyl-lysine into recombinant histones has been established in E. coli cells by WT MmPylRS214 or an MbPylRS variant (Y271F and C313T).215

Lysine butyrylation exists in histones and is involved in the onset and progression of cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases as well as growth, development, and metabolism of rice.216,217 OTSs for genetic encoding butyryl-lysine into proteins have been established in E. coli cells with WT MmPylRS214 or MbPylRS.215

Lysine crotonylation can be found in both histones and nonhistone proteins.218,219 Its unique C=C double bond forms a rigid planar conformation, indicating distinct regulatory mechanisms from other lysine acylation.220 OTSs based on WT MmPylRS214 or an MbPylRS variant (C313 V and M315Y)215 succeeded in site-specifically incorporating crotonyl-lysine into recombinant histones in E. coli cells. The protein yield was several milligrams per liter of growth media. Another OTS with an MbPylRS variant (L274A, C313F, and Y349F) was shown to genetically encode crotonyl-lysine into histones in human HEK293T cells, showing a promising application for in vivo studies.221

Lysine formylation occurs in histones and other nuclear proteins for regulating chromatin conformation and gene activity and functions as a secondary modification responding to oxidative DNA damage.222 MbPylRS was engineered to charge tRNAPyl with formyl-lysine, and a variant with five mutations (L266M, L270I, Y271F, L274A, and C313F) was able to generate homogeneously formylated proteins in both E. coli and mammalian cells.223 This work also demonstrated that the antibody for acetyllysine cannot recognize incorporated formyl-lysine residues, implying distinct regulatory functions between formylation and acetyllysine.

Lysine benzoylation has only been found in histones so far.208 It regulates gene expression of a series of proteins in metabolism and cell signaling.224,225 Several OTSs for benzoyllysine incorporation have been established. An MbPylRS variant (Y349W),226 an MmPylRS variant (Y384F),227 and an Methanomethylophilus alvus PylRS (MaPylRS) variant (Y206W)228 were shown to site-specifically incorporate benzoyl-lysine into target proteins in both E. coli and mammalian cells.

Due to the structural similarity among members of the nonpolar acylation group, those evolved PylRS variants have cross activities for different acylated lysine. For example, the OTS for propionyl-lysine can also encode crotonyl-lysine, while the OTS for crotonyl-lysine can incorporate both propionyl-lysine and butyryl-lysine.215 This phenomenon raises a question of how cells distinguish these highly similar modifications to implement different regulatory mechanisms.

7.3.2. Polar Acyl Groups.

Lysine 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation is widely distributed in both bacteria and eukaryotes, playing roles in protein synthesis, protein degradation, and cellular metabolism.229,230 The direct incorporation of 2-hydroxyisobutyryl-lysine into target protein has been successful in both E. coli and mammalian cells by an MbPylRS variant (C313T and Y349F).231

Lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation is a newly identified PTM in histones and nonhistone proteins in eukaryotes,232 which links cellular metabolism to gene expression.233 Emerging evidence shows its association with metabolic diseases, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, neuropsychiatric disorders, and cancers.234,235 A recent study showed that lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation could improve stability of COVID-19 antibodies in cells.236 The OTS for genetic encoding of lysine β-hydroxybutyrylation into proteins has been established in both E. coli and mammalian cells with an MbPylRS variant (C313 V and Y349F).237

Lysine lactylation is also a newly discovered PTM and can be found in both bacteria and eukaryotes.238,239 The same as β-hydroxybutyrate, lactate is an important metabolite in cells, so lysine lactylation also play roles in cellular metabolism and is associated with a series of diseases related to metabolism such as cancers, diabetes, and metabolic disorders.240 An MbPylRS variant (Y271 M and C313T) was evolved to site-specifically incorporate lactyl-lysine into proteins in both E. coli and mammalian cells.237

7.3.3. Charged Acyl Groups.

Lysine succinylation, malonylation, and glutarylation are three PTMs found in both histones and nonhistone proteins from eukaryotic and bacterial cells.241–243 They are mostly involved in cellular metabolism and stress responses.244 A special feature of these three lysine PTMs is that they change lysine residues from positively charged to negatively charged, making them distinct from other lysine acylation. This feature also challenges the development of OTSs for direct incorporation them into proteins by GCE due to their bulky sizes and negative charges. Alternatively, an indirect method was developed to generate proteins with site-specific lysine succinylation, malonylation, and glutarylation.245 The precursor azidonorleucine was first site-specifically incorporated into proteins by an MmPylRS variant (Y306L, C348I, and Y384F), followed by traceless Staudinger ligation with phosphinothioester with corresponding acyl moieties. Theoretically, this approach can be used to generate proteins with all kinds of lysine acylation.

7.3.4. Other Acylation.

Lysine lipoylation has been known to exist in a limited number of protein complexes such as pyruvate dehydrogenase and α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase as a handle to transfer reaction intermediates between subunits.246 A recent proteomic study identified a series of new protein targets for lysine lipoylation, indicating its possible roles in other biological processes.247 The OTS for installing lysine lipoylation has been developed in both E. coli and mammalian cells with an MbPylRS variant (Y271A, L274M, and C313V).237

Lysine fatty acylation with long chain fatty acyl groups such as myristoylation (C14) and palmitoylation (C16) has been identified in nonhistone proteins and is mostly involved in changing membrane protein affinity and localization for cell signaling.248 The long chain of fatty acids makes the direct incorporation of lysine myristoylation or palmitoylation into proteins almost impossible by GCE. A recent study developed an OTS for site-specifically installing lysine heptanoylation with a seven-carbon fatty acyl group into proteins with an MmPylRS variant (L301M, Y306A, L309A, and C348F) in E. coli cells.249 Although lysine heptanoylation has not been found in nature yet, the OTS could still provide a tool for studying native lysine fatty acylation.

Lysine aminoacylation is a newly identified PTM catalyzed by corresponding aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases to sense and transmit intracellular amino acid signals.250 As one type of lysine aminoacylation, lysine threonylation has been found in more than 100 proteins. The OTS for genetic encoding threonyl-lysine into proteins has been recently established in both E. coli and mammalian cells with an MmPylRS variant (Y384F).251 Later, another lysine aminoacylation, methionyllysine, was site-specifically incorporated into proteins by an MbPylRS variant (L274A, C313S, and Y349F) in both E. coli and mammalian cells. Using such a protein as a probe, a new PTM aminoacylated lysine ubiquitination was identified in human cell lines.252

7.3.5. Acylation Analogs.

Besides the above-mentioned lysine acylation, which exists in nature, a series of lysine acylation analogs have also been genetically encoded into proteins: A) Stable mimics for in vivo studies. Pent-4-ynyloxycarbonyl-lysine was used as a stable mimic of lysine butyrylation to study Salmonella infection, which can be genetically encoded into proteins by the OTS with an MbPylRS variant (L274A, C313S, and Y349F);253 B) Probes for biophysical studies. 2-Fluorobenzoyl-lysine and 2,5-difluorobenzoyl-lysine were site-specifically incorporated into proteins by an MmPylRS variant (Y384F) as probes for 19F NMR to monitor protein structure and interaction;227 C) Chemical handles for detectable tags. 7-Octenoyl-lysine and 7-azidoheptanoyl-lysine were site-specifically incorporated into proteins by an MmPylRS variant (L309A and C348S) first and then reacted with a fluorogenic tetrazine dye through the alkene-tetrazine cycloaddition reaction or a dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) dye through click chemistry to detect deacetylation by sirtuins;254,255 D) Photo-cross-linkers for mapping interaction networks. Diazirine-containing photoaffinity crotonyl-lysine was first genetically encoded into proteins by an MmPylRS variant (L309A, C348F, Y384W). After exposure with UV 365 nm, biomolecules that interact with target proteins were photo-cross-linked and identified by mass spectrometry.256 Recently, this strategy was extended to other lysine acylation such as propionylation, butyrylation, 2-hydroxyisobutyrylation,and β-hydroxybutyrylation.257

7.4. Lysine Ubiquitination/SUMOylation

Lysine ubiquitination is the most abundant lysine PTM in nature and can be found in proteins involved in a wide range of biological processes, not only confined to its well-known role in directing protein degradation.258,259 Ubiquitin (Ub) is a small protein with 76 amino acid. The C-terminal glycine residue of Ub is covalently linked to specific lysine residues in substrate proteins through an isopeptide bond by a successive process catalyzed by three enzymes: E1 Ub-activating enzyme, E2 Ub-conjugating enzyme, and E3 Ub-ligase.260 Beyond monoubiquitination, Ub can also attach to one of seven lysine residues or the N-terminal methionine residue in other Ub units to form polyubiquitination.15 Besides Ub, there are also some Ub-like proteins such as SUMO and NEDD8 that have similar properties to Ub, making the profile of ubiquitination in cells more complicated.261 Thus, it is necessary to generate proteins with homogeneous ubiquitination or SUMOylation to determine its site-specific roles. Although direct incorporation of ubiquitinated/SUMOylated lysine into protein is impossible for the GCE strategy due to their large sizes, numerous efforts have been made to generate homogeneously ubiquitinated/SUMOylated proteins by ncAA-mediated approaches.

In an earlier study, a thiol-containing lysine, D-Cys-ε-lysine, was first genetically encoded into proteins by WT PylRS, then reacted with a Ub analog with a C-terminal thioester by thiol exchange, followed by intramolecular S- to N-acyl transfer to form a ubiquitinated protein in vitro (Figure 21A).262 However, this method cannot generate the native isopeptide bond between Ub and lysine residues. To achieve this goal, a method called GOPAL (genetically encoded orthogonal protection and activated ligation) was developed with a similar procedure of generating lysine methylation shown in Figure 18A. Instead, it used a Cbz-protected Ub with a C-terminal thioester as the Ub donor.263 Although this approach generates ubiquitinated proteins with native isopeptide linkage, it is a relatively laborious process. To address this concern, a more facile method was established later.264 A thiol-lysine precursor, p-nitrocarbobenzyloxy-thiol-lysine, was first site-specifically incorporated into proteins by an OTS with an MbPylRS variant (Y271M, L274G, C313A, and Y349W) and converted to thiol-lysine by reductive decaging, followed by native chemical ligation with a Ub thioester. The thiol group was then removed by desulfurization reagent to generate ubiquitinated proteins in vitro (Figure 21B).

Figure 21.

The generation of lysine ubiquitination in proteins by ncAA-mediated approaches. The ubiquitin moiety is linked to lysine residues by A) native chemical ligation with D-Cys-ε-lysine; B) native chemical ligation with thiol-lysine; C) click chemistry with 2-propynyloxycarbonyl-lysine; D) oxime ligation with aminooxy-lysine; E) sortase-catalyzed transpeptidation with glycyl-glycyl-lysine.

Lysine ubiquitination is a reversible PTM, and the removal of ubiquitin moieties is catalyzed by deubiquitinases.265 To generate stable ubiquitinated proteins, nonhydrolyzable ubiquitination analogs have been incorporated into proteins by ncAA-mediated approaches. By using click chemistry, an alkynyl-containing lysine derivative, 2-propynyloxycarbonyllysine, was first genetically encoded into protein by WT MbPylRS and then reacted with azide-containing Ub (Figure 21C).266 In another work, the biorthogonal oxime ligation reaction was used to link aldehyde-containing Ub and aminooxy-lysine-containing proteins (Figure 21D). The aminooxy-lysine was first protected by a Boc group, then site-specifically incorporated into protein by an MbPylRS variant (Y349W), and finally deprotected by TFA treatment.267

All these methods mentioned above only apply to in vitro studies with purified proteins. To overcome this limitation, an ncAA-mediated approach combines biocompatible chemical and enzymatic reactions to generate proteins with site-specific lysine ubiquitination mimics in vivo (Figure 21E).268 Instead of linking Ub moiety to lysine residues by chemical reactions in above-mentioned approaches, an enzyme called sortase A was used for this step. Sortase A is an enzyme from Staphylococcus aureus and covalently links proteins to cell wall.269 It recognizes a specific motif LPXTG, cuts between T and G, and attaches T to peptides containing N-terminal glycine residues. To link Ub to a lysine residue, the C-terminal sequence of Ub was mutated from LRLRGG to LPLTGG. Then the remaining GG moiety need to attach to a lysine residue in the target protein. To achieve the goal, the GCE strategy was applied to site-specifically incorporate the GG moiety containing-lysine precursor, 2-azidoacetyl-glycyl-lysine, by an MbPylRS variant (L274A, N311Q and C313S), which was then converted to glycyl–glycyl-lysine by Staudinger reduction with the cell-permeable phosphine 2-(diphenylphosphino)benzoic acid in living cells. The final protein product has the native isopeptide linkage between Ub and lysine but also bears two mutations at the C-terminal of Ub (R72P and R74T), making the ubiquitinated protein resistant to deubiquitinases. This work also used the same strategy to install lysine SUMOylation into proteins in living mammalian cells. Later, a series of orthogonal sortases and asparaginyl endopeptidases were engineered to provide more flexible motif selections.270,271

8. SERINE/THREONINE MODIFICATIONS

Serine and threonine are two polar amino acids with hydroxyl groups, making them favorable targets of PTMs. Besides well-known phosphorylation and O-glycosylation, both of them also undergo several relatively rare PTMs such as acetylation, which can compete with other PTMs to have antagonized effects,272 sulfonation, which is involved in protein assembly and signal transduction,273 and palmitoylation, which regulates membrane protein functions.274 In this section, we focus on the development of OTSs for generating proteins with homogeneous phosphorylation or O-glycosylation on serine or threonine residues.

8.1. Serine Phosphorylation

Serine phosphorylation is the most abundant PTM in nature. The addition of the phosphate group brings two negative charges to the serine residue, affecting protein structure, function, and interactions.275 Due to the transferable property of the phosphate group, phosphorylation plays essential roles in cell signaling pathways, regulating a variety of processes including cellular metabolism, cell cycle, cell differentiation, and stress responses276,277 Because of its tight association with human diseases, phosphorylation is a common therapeutical target.278,279 Protein phosphorylation is regulated by kinases and phosphatases. In humans, there are more than 500 kinases and approximately 200 phosphatases,280,281 making phosphorylation involved in a huge cell signaling network. To illustrate the effects of phosphorylation on target proteins, enzymatic, chemical, and biological approaches have been developed to generate phosphorylated proteins.12,282 Among these methods, GCE is able to generate site-specifically phosphorylated proteins in living cells, providing a powerful tool to study protein phosphorylation in vivo. The applications of GCE in characterizing specific phosphorylation events have been nicely reviewed recently.51,283

Phosphoserine (Sep) is not a synthetic amino acid, but a native amino acid in cells, which is an important intermediate in serine biosynthesis.284 In methanogenic archaea, phosphoseryl-tRNA synthetase (SepRS) charges tRNACys with Sep for cysteine biosynthesis.285 Inspired by this fact, the pair of Methanococcus maripaludis SepRS (MmSepRS) and a modified MjtRNACys with CUA as the anticodon (tRNASep) was used to generate Sep-tRNASep, which is later delivered to ribosomes by EF-Tu to decode the UAG codon in mRNA as Sep. However, ET-Tu has a relatively weaker binding with negatively charged amino acids due to two acidic amino acid residues in the amino acid binding pocket.286 Thus, E. coli EF-Tu was engineered to accommodate Sep-charged tRNASep (EF-Sep) with mutations of H67R, D216G, E217N, F219Y, T229S, and N274W. MmSepRS, tRNASep, and EF-Sep forms the first OTS for Sep incorporation in E. coli cells (Figure 22).287 To date, Sep-OTSs have been introduced into Samonella,166 mammalian cells,288 and cell-free translation systems.71,289

Figure 22.

Genetic encoding phosphoserine into proteins in living cells and further optimization. Phosphoserine (Sep) is linked to tRNACysCUA by phosphoseryl-tRNA synthetase (SepRS) to generate Sep-tRNA, which is then delivered to the ribosome by an EF-Tu variant, EF-Sep, to decode UAG codon in mRNA as Sep, thus generating the target protein with site-specific serine phosphorylation. To improve Sep-incorporation, several strategies have been adopted, including inactivating serine phosphatase to increase intracellular Sep concentration, inactivating release factors to eliminate early termination, using nonhydrolyzable Sep mimics to prevent hydrolysis by protein phosphatases, and further engineering SepRS, tRNACysCUA, and EF-Sep.

The first Sep-OTS could only produce phosphorylated proteins at the microgram level. To improve Sep incorporation efficiencies, components in the whole process of Sep-encoding have been optimized (Figure 22). A) Serine phosphatase inactivation. Inactivation of serine phosphatase (SerB in E. coli or PSPH in mammalian cells) can increase the intracellular Sep concentration to provide sufficient substrate for generating Sep-charged tRNA.288,290–292 B) Removal of release factor-1 (RF1). One major factor to affect UAG codon-mediated ncAA incorporation is the competition from RF1 in E. coli cells. To eliminate such competition, RF1 has been inactivated in E. coli strains. However, one problem with RF1-deficient strains is that there are hundreds of native genes in E. coli using TAG as the termination signal. Inactivation of RF1 will add unwanted C-terminal extension to those proteins, and some of them are essential for E. coli cells. Thus, partial or complete replacement of those TAG codons with TAA codons was implemented to recover cell growth and to increase Sep-incorporation in E. coli cells, including the EcAR7.ΔA strain in which stop codons of 7 essential genes in E. coli were modified from TAG to TAA,290,293 the C321.ΔA strain in which all 321 TAG codons in E. coli MG1655 cells were changed to TAA codons,289,294,295 and the B-95.ΔA stain in which 95 TAG codons in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells were mutated to TAA.296 Another strategy to overcome the drawback of RF-1 deficient strains is to remove near cognate tRNAs for UAG codons to prevent the decoding of UAG codons as canonical amino acids such as tyrosine and glutamine. This strategy has been used in cell-free translation systems for phosphoprotein synthesis.71 C) Further engineering SepRS, tRNASep, and EF-Sep. Further engineering each component in the Sep-OTS has been implemented by generating larger mutation libraries, optimizing selection strategies, or hybridizing components from different species, which includes the SepRS9-EFSep21 system with an optimized MmSepRS variant (K347E, N352D, E412S, E414I, P495R, I496R and L512I) and an optimized E. coli EF-Tu variant (H67R, D216 V, E217N, F219Y, T229S, and N274W),297 the SepRSv1.0/tRNAv1.0CUA pair with an improved MmSepRS variant (E412P, E414F, K417 K, P495M, I496W, and F529) and an enhanced MjtRNASep mutant (A29G, U31A, A39U, U40C, and U41C) without the need of EF-Tu variants,292 as well as an OTS that contains SepRSv1.0/tRNAv1.0CUA, an EF-1α variant (EF-1α-Sep, L77R, Q251N, D252G, V264S, andN307W), and eRF1(E55D) for Sep-incorporation in mammalian cells.288 D) Nonhydrolyzable Sep analogs. Protein phosphatases in cells can dephosphorylate phosphoproteins generated by GCE. Thus, a nonhydrolyzable Sep analog, phosphonomethylene alanine (Pma), was genetically encoded into proteins in both E. coli and mammalian cells.288,292 Due to the high similarity between Pma and Sep, Pma can be recognized by SepRS. However, endogenous Sep in cells can also compete with Pma for the Sep-OTS. To increase Pma-incorporation, endogenous Sep concentration was decreased by overexpressing serine phosphatase (SerB in E. coli or PSPH in mammalian cells) to hydrolyze free Sep and inactivating phosphoserine aminotransferase (SerC in E. coli or PSAT in mammalian cells) to block the production of Sep.288,292

8.2. Threonine Phosphorylation

Threonine is different from serine only by one methyl group, but that methyl group matters. That is why nature keeps both serine and threonine as basic components for protein synthesis after billions of years of evolution. The abundance of serine phosphorylation in nature is about 4.5-fold that of threonine phosphorylation.298 The structure and function of serine phosphorylation and threonine phosphorylation also differ from each other.299

Because of the similarity between Sep and phosphothreonine (pThr), the established Sep-OTS is a good start for pThr-OTS development. To achieve this goal, there are two concerns to be addressed first. pThr does not exist as a free amino acid in most species such as E. coli and mammalian cells, which are the most common hosts for GCE, and negatively charged compounds commonly have low cellular uptake. Thus, the first problem is how to increase intracellular pThr concentration for pThr-tRNA generation. PduX, a threonine kinase in Salmonella, generates pThr as an intermediate for coenzyme B12 biosynthesis.300,301 Overexpressing PduX can increase pThr concentration in E. coli cells.302 The second problem to be solved is how to engineer SepRS to recognize pThr but not Sep. Combining parallel selection and deep sequencing, an MmSepRS variant (G320A and L321Y) was shown to distinguish Sep and pThr, and site-specifically incorporated pThr into target proteins in E. coli cells.302 A recent study further optimized the pThr-OTS with several modifications such as inactivating phosphoserine aminotransferase SerC to decrease Sep concentration and utilizing RF-1 deficient strains to generate proteins with site-specific threonine phosphorylation.303 Next steps for pThr-OTS development will be introducing it into mammalian cells and genetic encoding nonhydrolyzable pThr analogs.

8.3. O-Glycosylation

Besides N-glycosylation discussed in section 4.1, O-glycosylation is another type of protein glycosylation with O-linkage between glycans and hydroxyl group-containing amino acid residues, including serine, threonine, hydroxyproline, hydroxylysine, and rarely tyrosine.304 In addition to the roles in protein localization and cell signaling, emerging evidence has demonstrated the involvement of O-glycosylation in protein aggregation and phase separation.305 O-glycosylation has been found to be associated with genetic disorders, infectious diseases, immune-related diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancers.306,307

Chemical and enzymatic approaches have been implemented to generate proteins with O-glycosylation mimetics. The site-directed mutated cysteine residue is transformed into Dha by alkylating reagents and reacted with active glycosylation derivatives.308,309 Furthermore, thioglycoligase engineered from Streptomyces plicatus hexosaminidase is able to transfer N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) to a site-directed mutated cysteine residue to form a protein with S-GlcNAc, which is a physiological mimetic of O-glycosylation.310 However, both methods only apply to in vitro studies with purified proteins.

Although direct incorporation of O-glycosylated serine/threonine into proteins in living cells has not been established yet, the applications of GCE in cell-free translation systems to produce glycosylated proteins have been reported earlier.311,312 Instead of charging tRNA with glycosylated amino acids by engineered AARSs, chemical or T4 ligase-catalyzed aminoacylation was used to aminoacylate tRNA, which later decodes the assigned codon as glycosylated amino acids. For cell-based approaches, several OTSs have been utilized to genetically encode ncAAs bearing functional groups, which can be reacted with glycan moiety-containing compounds to form glycosylated proteins. For example, a similar approach shown in Figure 11 was applied. First, bicyclo[6.1.0]nonyne-lysine was site-specifically incorporated into proteins by an MmPylRS variant (Y306A and Y384F) in E. coli cells. Then purified proteins were reacted with a tetrazine-containing glucosamine analog by the inverse-electron-demand Diels–Alder reaction to form glycosylation mimic-containing proteins in vitro.313 Since the inverse-electron-demand Diels–Alder reaction can be applied in living cells, this approach has the potential for in vivo studies. In another work, like the method demonstrated in Figure 21C, click chemistry was utilized to link alkyne-containing residues with azido-containing glycans to produce target proteins with glycosylation mimics in vitro.314

9. TRYPTOPHAN MODIFICATIONS

Tryptophan is an aromatic amino acid with an indole ring as the side chain and is commonly found inside of globular proteins. Its intrinsic fluorescence makes itself a native probe for detecting protein conformational changes.315 Tryptophan residues in proteins mainly undergo oxidation and nitration, which is involved in stress responses to reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) (Figure 23).316,317 In this section, we focus on the development of OTSs for genetically encoding tryptophan hydroxylation, one type of tryptophan oxidation.

Figure 23.

Tryptophan oxidation and nitration modifications found in proteins.

9.1. Tryptophan Hydroxylation

Tryptophan hydroxylation has been found in a series of proteins such as α-crystallin and apolipoprotein. α-crystallin is a major lens protein, and oxidation of tryptophan residues in crystallin leads to darkening of lens and a potential link to cataractogenesis.318 Oxidation of tryptophan residues in apolipoprotein can decrease cholesterol efflux capacity.319 It is commonly thought that protein oxidation is harmful. However, oxidation of tryptophan residues does not always have negative effects and sometimes is essential for protein functions.316 For example, copper-binding protein MopE in Methylococcus capsulatus needs oxidation of tryptophan residues to facilitate the binding of copper.320 Thus, it is necessary to characterize site-specifically hydroxylated tryptophan residues.