Abstract

The transition from G1 to S phase in the cell cycle requires sequential activation of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (cdk4) and cdk2, which phosphorylate the retinoblastoma protein, causing the release of E2F. Free E2F upregulates the transcription of genes involved in S phase and cell cycle progression. Recent studies from this and other laboratories have shown that herpes simplex virus 1 stabilizes cyclin D3 early in infection and that early events in viral replication are sensitive to inhibitors of some cdks. On the other hand cdk2 is not activated. Here we report studies on the status of members of E2F family in cycling HEp-2 and HeLa cells and quiescent serum-starved, contact-inhibited human lung fibroblasts. The results show that (i) at 8 h postinfection or thereafter, E2F-1 and E2F-5 were posttranslationally modified and/or translocated from nucleus to the cytoplasm, (ii) E2F-4 was hyperphophorylated, and (iii) overall, E2F binding to cognate DNA sites was decreased at late times after infection. These results concurrent with those cited above indicate that late in infection activation of S-phase genes is blocked both by posttranslational modification and translocation of members of E2F family to inactive compartments and by the absence of active cdk2. The observation that E2F were also posttranslationally modified in quiescent human lung fibroblasts that were not in S phase at the time of infection suggests that specific viral gene products are responsible for modification of the members of E2F family and raises the possibility that in infected cells, activation of the S phase gene is an early event in viral infection and is then shut off at late times. This is consistent with the timing of stabilization of cyclin D3 and the events blocked by inhibitors of cdks.

Studies from this and other laboratories have shown that herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) infection of susceptible cells has a profound effect on the infected cell (28). More recent studies have focused on the effect of viral gene products on the proteins that regulate the cell cycle. The studies described in this report have as their genesis the observation that the HSV-1 promiscuous transactivator infected-cell protein 0 (ICP0) stabilizes cyclin D3 without affecting its interaction with cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (cdk4) or phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein (pRb) (17). In later studies, it was shown that substitution of a single amino acid in ICP0 abrogates the binding and stabilization of cyclin D3 and reduces the neuroinvasiveness of the mutant from a peripheral site (38). The observation that other herpesviruses either bind the cyclin D appropriate for the cells in which they replicate (Epstein-Barr virus) or encode a functional D cyclin homolog (human herpesvirus 8 and herpesvirus saimiri) suggested that herpesviruses depend on the function of D cyclins for optimal replication and raised the possibility that this function involves activation of S-phase-related genes (19, 25, 33, 35, 36). One well-characterized function of cyclin D is to complex with cdk4 or cdk6 and to phosphorylate pRb (16, 21). In the process, pRb releases its grip on E2F. In turn, free E2F binds to cognate sites in promoters of genes expressed during S phase (5, 11, 14). A central question therefore is whether the stabilization of cyclin D3 in cells infected with wild-type HSV-1 causes an increase in the free E2F proteins measured by their binding to cognate DNA sites. This report deals with cells infected within a short time after synchronization and infection of quiescent human fibroblasts. We report that in these cells the levels of E2F capable of binding to cognate sites on its DNA remained similar to that of uninfected cells during the first 4 h after infection but was reduced at least sixfold between 4 and 8 h after infection in cycling and by 30% in quiescent cells. Of particular interest is the emergence in HSV-1-infected cells of E2F-1, E2F-2, E2F-4, and E2F-5 protein characterized by altered mobility in denaturing gels. Relevant to this report are the following findings.

(i) The E2F family of transcription factors is currently composed of six known members (E2F-1 to E2F-6). The E2F family members can be classified into two groups. E2F-1, -2, and -3 accumulate in a cell cycle-dependent manner, have a nuclear localization signal, and induce S-phase progression (24, 39). E2F-4 and -5 levels are relatively constant throughout the cell cycle, their subcellular localization is dependent on associated proteins, and they are poor inducers of S phase. All family members form heterodimers with DP1 or DP2 (reviewed in references 2 and 11). The transcriptional activity of E2F is repressed when complexed to pRb pocket proteins (10). The transition from G1 to S phase involves sequential activation of cyclin D-cdk4 and cyclin E-cdk2 kinase complexes (22). Both cyclin D-cdk4 and cyclin E-cdk2 phosphorylate pRb to release E2F and initiate the transcription of E2F-dependent genes.

(ii) E2F-1, the most thoroughly characterized member of the E2F family, is capable of activating transcription of a variety of genes involved in cellular DNA synthesis (DNA polymerase α-dihydrofolate reductase and ribonucleotide reductase) and cell cycle progression (cdk2 and cyclin A) (5, 11). E2F-1 can function as both an oncogene and a tumor suppressor. An apparently contradictory function of E2F-1 is its role in promoting apoptosis (9, 42). The induction of apoptosis by E2F-1 is in part mediated by its ability to bind DNA.

(iii) At least three families of DNA viruses have been reported to encode viral proteins that accelerate the onset of S phase in the infected cell by targeting the release of E2F from pRb (6, 7). Thus, the adenovirus E1a, the papillomavirus E7, and simian virus-40 T antigen have been reported to disrupt pRb-E2F complexes (4, 6, 40).

In addition to the studies reported above (17, 38) recently several laboratories have reported on the effects of HSV-1 infection on cellular proteins involved in cell cycle regulation. (i) Replication of HSV-1 is reduced in cells following the addition of high concentrations of inhibitors of cdk2, cdc2, and cdk5 (15, 30–32). (ii) HSV-1 causes the activation of the G2/M kinase cdc2 even though cyclin A and B levels are reduced (1). (iii) Overexpression of ICP0 results in cell cycle arrest at the G1 and G2/M phases (13, 20). (iv) HSV-1 infection results in a block in S-phase progression and hypoactivated cdk2 (3, 7). (v) A fraction of pRb in HSV-1 infected cells is alternatively phosphorylated (30). (vi) pRb and p53 have been reported to localize to sites of viral DNA replication in HSV-1-infected cells (41). (vii) HSV-1 induces in infected cells free and heteromeric forms of E2F as measured by gel shift assays (12). (vii) E2F-4 is translocated from the cytoplasm into the nucleus following infection, which is reminiscent of the G0 phase of the cycle (26).

Since some viruses target pRb and cytomegalovirus phosphorylates E2F proteins (23, 27), the objective of this study was to characterize the effect of HSV-1 infection on E2F and the ability of HSV-1-modified E2F to bind to DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

HeLa and HEp-2 were initially obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with 10% newborn calf serum. Human embryonic lung (HEL) fibroblasts were obtained from Aviron (Mountain View, Calif.) and maintained in 5% newborn calf serum. HSV-1(F) is the prototype wild-type HSV-1 strain used in our laboratory (8).

Cell infection.

Confluent 150-cm2 flasks of HeLa or HEp-2 cells were harvested and plated on 25-cm2 flasks. Cells were allowed to adhere for 1 h, after which unattached cells were aspirated. The attached cells were then exposed 2 × 107 PFU of HSV-1(F) in 1 ml of 199V (medium 199 supplemented with 1% calf serum) and placed on a rotary shaker at 37°C. After 2 h, the inoculum was replaced with 5 ml of fresh Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% newborn calf serum, and the culture were incubated at 37°C until the cells were harvested. Flasks (150 cm2) of HEL fibroblasts were grown to confluence and held at confluence for 1 week to achieve contact-inhibited and serum-starved conditions. Quiescent HEL fibroblasts were infected as follows. Spent medium was aspirated from the flasks and saved; 2 × 108 PFU of HSV-1(F) was added to 6 ml of spent medium and overlaid on the cells. Mock-infected cells were treated by the addition of a similar volume of milk buffer into the spent medium. Infection proceeded for 2 h at 37°C on a rotary shaker, after which the inoculum was replaced with 25 ml of spent medium.

Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractionation.

Cells were harvested at various time points as follows. The medium was removed; the cells were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), scraped into 5 ml of PBS, and pelleted by centrifugation. The cell pellet was gently resuspended in hypotonic lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 10 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.05% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) by gently pipetting up and down 10 times and kept on ice for 30 min. The lysate was pelleted at 2,500 rpm (500 × g) for 5 min at 4°C. The cytoplasmic fraction (supernatant) was transferred to a new tube. The pelleted nuclei were gently washed in hypotonic lysis buffer and pelleted as above. The nuclei were lysed by resuspending the pellet in high-salt lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 250 mM KCl, 0.1% NP-40, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaF, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 5% glycerol) and stored on ice for 30 min. The lysate was spun down at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations of the nuclear and cytoplasmic fraction were determined using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Protein concentrations were then equalized between mock- and HSV-1(F)-infected cells.

E2F oligonucleotide labeling.

E2F consensus DNA binding oligonucleotide was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-2507). Alternatively, oligonucleotides were synthesized to the E2 promoter sequence and dihydrofolate reductase promoter sequence corresponding to E2F binding sites. The oligonucleotide was end labeled with 32P as follows. Three picomoles of oligonucleotide, 150 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, 15 U of bacteriophage T4 polynucleotide kinase, and bacteriophage T4 polynucleotide kinase buffer were reacted in 20 μl (total volume) at 37°C for 45 min. The T4 polynucleotide kinase was inactivated by heating the reaction mixture at 68°C for 10 min. Labeled oligonucleotide was separated from free [γ-32P]ATP by Sephadex G-50 spin column chromatography and stored at −20°C.

E2F electrophoretic mobility shift and supershift assays.

The binding reaction mixture contained 0.5 to 10 μg of protein, 3 μg of poly(dI-dC), 0.5 ng of 32P-labeled E2F consensus sequence oligonucleotide, binding buffer (5× = 100 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 200 mM KCl, 30 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 25% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40, 5 mM EDTA). The binding reaction was brought up to a total volume of 20 to 30 μl. Binding reactions mixtures with unlabeled cold excess of E2F oligonucleotide consensus binding sequence had 50 ng (100-fold excess) of unlabeled E2F consensus sequence oligonucleotide. Binding reactions were carried out for 20 min at room temperature. Samples were then loaded onto 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels and subjected to electrophoresis in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer for 75 min at 180 V. Gels were dried and analyzed by a PhosphorImager (Storm 860; Molecular Dynamics) and autoradiography.

Supershift assays described initially by Kristie and Roizman (18) were done as follows. The reaction was carried out in 20 μl (total volume). After addition of the labeled probe, the reaction mixture described above was stored for 20 min at room temperature. Then 2 μl of appropriate antibody was added, and the reaction mixtures were stored for an additional 30 min at room temperature and then loaded onto gels as above.

Immunoblotting.

Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were denatured by boiling in disruption buffer (final concentration of 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 50 mM Tris [pH 7.2], 2.75% sucrose, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, and bromophenol blue) was added to equivalent amounts of protein from samples. The extracts were boiled for 5 min, subjected to electrophoresis on 8 or 10% bisacrylamide gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked for 2 h with 5% nonfat dry milk, and reacted with the appropriate antibody. Antibodies against E2F-1, E2F-2, E2F-3, E2F-4, and E2F-5 (Santa Cruz) were diluted 1:200 in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 and 1% bovine serum albumin and reacted for 2 h at room temperature. The immunoblots were exposed to the secondary antibodies diluted 1:3,000 (alkaline phosphatase [AP] conjugated [Bio-Rad] or peroxidase conjugated [Sigma]) for 1 h. To develop AP-conjugated secondary antibodies, the immunoblots were reacted with AP buffer (100 mM Tris [pH 9.5], 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2), followed by AP buffer containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate and nitroblue tetrazolium. The reaction was stopped by the addition of Tris (pH 7.6) and 10 mM EDTA. Peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were developed by enhanced chemiluminescence according to instructions supplied by the manufacturer (Pierce). All rinses were done in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20.

AP treatment.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of cells were harvested as above except that lysis was done with or without the addition of phosphatase inhibitors (NaF, β-glycerophosphate, and sodium orthovanadate) to the hypotonic and high-salt lysis buffers. Equivalent amounts of protein from samples were reacted with 5 U of calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (CIAP) and appropriate reaction buffer for 30 min at 34°C. Reactions were stopped by the addition of gel loading buffer. Samples were assayed by immunoblotting as described above.

RESULTS

HSV-1 infection results in the accumulation of novel isoforms of E2F-1 in cycling cells and accumulation of a high-molecular-weight isoform in quiescent cells.

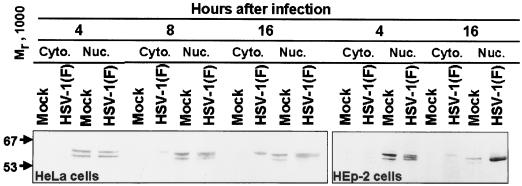

Infected or mock-infected HEp2 or HeLa cells were fractionated into nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts. The lysates were subjected to electrophoresis in a denaturing gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose sheet, and reacted with antibodies to E2F-1. E2F-1, a predominantly nuclear protein, was found almost exclusively in the nuclear fraction of uninfected HeLa or HEp2 cells (Fig. 1). The results show that at 4 h after infection, nuclear extracts of infected HeLa cells formed two prominent E2F-1 bands that could not be differentiated from those of mock-infected cells. An additional E2F-1 band migrating between the two prominent bands was formed by lysates of HeLa cells harvested at 8 or 16 h after infection. This E2F-1 band specific for HSV-1-infected cells was formed by lysates of HEp-2 cells harvested as early as 4 h after infection (Fig. 1). While the cytoplasmic fractions of mock-infected HeLa or HEp2 cells harvested at 4, 8, or 16 h after infection contained only trace amounts of E2F-1, the cytoplasmic fraction of cells harvested at 8 and 16 h (HeLa) or 16 h (HEp-2) after infection each formed a single prominent E2F-1 band (Fig. 1). The electrophoretic mobility of this band was slower that of bands formed by nuclear extracts of mock-infected or infected cells.

FIG. 1.

Immunoblot of cytoplasmic (Cyto.) and nuclear (Nuc.) fractions of uninfected or HSV-1(F)-infected HeLa and HEp-2 cell lysates separated on bisacrylamide gels and reacted with antibody to E2F-1 as described in Materials and Methods. The cells were infected at time zero and harvested at the indicated times after infection.

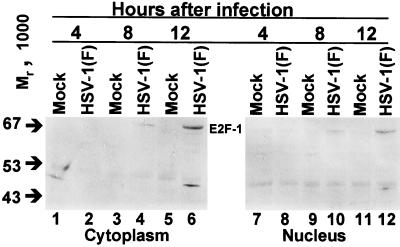

Quiescent mock-infected cells had low levels of E2F-1 as expected since E2F-1 transcription is cell cycle dependent (Fig. 2). In contrast, infected cells accumulated a high-molecular-weight E2F-1 species (Fig. 2). This form is present at relatively low levels in mock-infected cells but was readily detected in both nuclei and cytoplasm by 8 h after infection. In view of the results shown above, it was of interest to determine whether other E2F family members were also modified following infection with HSV-1(F).

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of uninfected or HSV-1(F)-infected serum-starved, contact-inhibited HEL fibroblasts lysates separated on bisacrylamide gels and reacted with antibody to E2F-1. Cells were infected at time zero and harvested at the indicated times after infection.

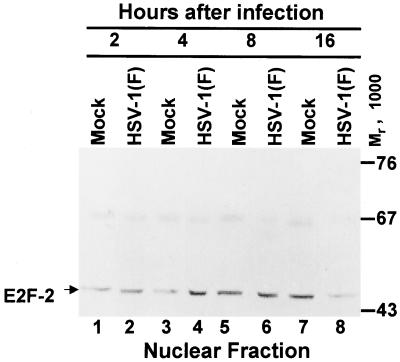

E2F-2 accumulates in decreased amounts in infected cells.

The results of an experiment similar to those reported above indicated that the quantity and electrophoretic mobility of E2F-2 accumulating in cells during the first 8 h after infection could not be differentiated from that of mock-infected cells in cycling HEp-2 cells (Fig. 3). At 16 h after infection, there was a decrease in the accumulation of nuclear E2F-2 (Fig. 3). In HEL fibroblasts, nuclear E2F-2 migrated as a doublet (Fig. 4). In mock-infected cells, there was an equivalent amount of each isoform of E2F-2, whereas HEL fibroblasts accumulated predominantly the upper form of E2F-2 at 8 and 12 h after infection. A small but equal proportion of E2F-2 was found in the cytoplasm of mock-infected or HSV-1-infected cells between 4 and 12 h after infection (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot of nuclear fractions of uninfected or HSV-1(F)-infected HEp-2 cell lysates separated on bisacrylamide gels and reacted with antibody to E2F-2. Cells were infected at time zero and harvested at the indicated times after infection.

FIG. 4.

Immunoblot of nuclear fractions of uninfected or HSV-1(F)-infected serum-starved, contact-inhibited HEL fibroblasts lysates separated on bisacrylamide gels and reacted with antibody to E2F-2. Cells were infected at time zero and harvested at the indicated times after infection.

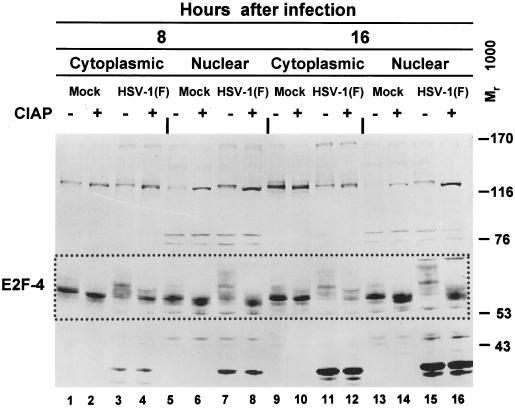

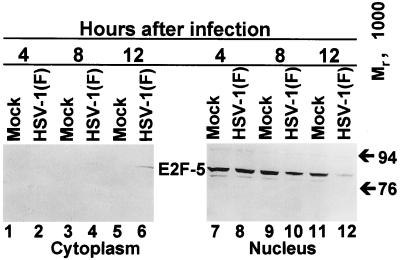

HSV-1 causes posttranslational modification of E2F-4.

It was reported earlier (26) that E2F-4 was modified and translocated to the nucleus of HSV-1-infected cells. Our studies of E2F-4 yielded the following results. (i) In noninfected HEp-2 cells, E2F-4 localized in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions and formed one major band and several fainter, both faster- and slower-migrating bands (Fig. 5, lanes 1, 5, 9, and 13). In HSV-1-infected cells, E2F-4 present in both cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions formed a large number of bands that tended to increase in Mr range from 55,000 to 76,000 with time after infection (lanes 3, 7, 11, and 15). The high-apparent-molecular-weight bands were particularly prominent in electrophoretic profiles of nuclear fractions of infected cells (lanes 7 and 15).

FIG. 5.

Immunoblot of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of uninfected or HSV-1(F)-infected HEp-2 cell lysates treated with or without CIAP, separated on bisacrylamide gels, and reacted with antibody to E2F-4. Cells were infected at time zero and harvested at the indicated times after infection. The boxed region indicates the isoforms of E2F-4 detected.

E2F-4 formed three closely migrating isoforms and accumulated predominantly in the nuclear fraction of mock-infected HEL fibroblasts (Fig. 6, lanes 7, 9, and 11). HSV-1-infected cells accumulated the highest-apparent-molecular-weight species of E2F-4 by 8 h after infection (lanes 4 and 10) in both cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions which remained at 12 h after infection (lanes 6 and 12).

FIG. 6.

Immunoblot of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of uninfected or HSV-1(F)-infected serum-starved, contact-inhibited HEL fibroblasts lysates separated on bisacrylamide gels and reacted with antibody to E2F-4. Cells were infected at time zero and harvested at the indicated times after infection. Multiple E2F-4-reactive bands were observed as indicated by the vertical lines.

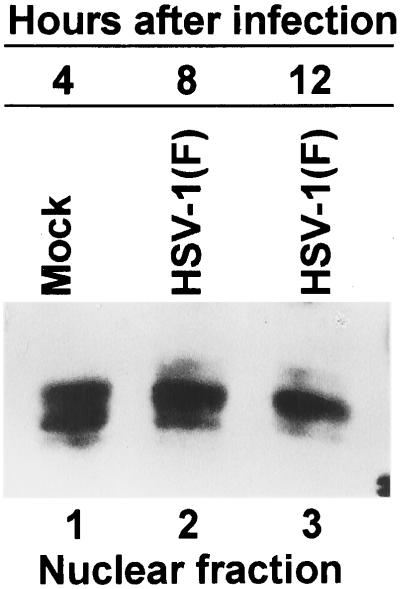

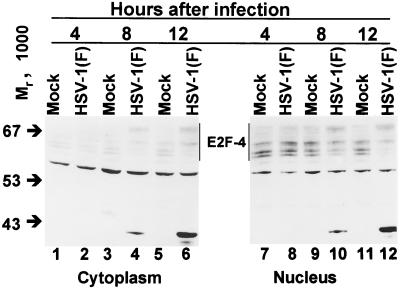

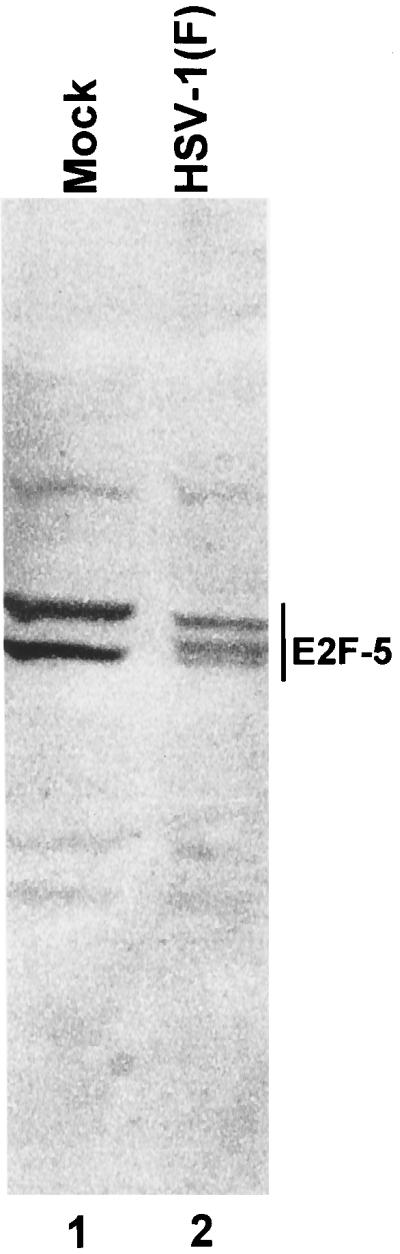

HSV-1 effects on E2F-5.

E2F-5 present in mock-infected HEp-2 cells revealed two prominent bands (Fig. 7, lane 1). E2F-5 in lysates of cells harvested at 14 h after infection with HSV-1 accumulated in addition a third isoforms whose electrophoretic mobility was intermediate between those of the two isoforms present in mock-infected cells (lanes 1 and 2).

FIG. 7.

Immunoblot of nuclear fractions of uninfected or HSV-1(F)-infected HEp-2 cell lysates separated on bisacrylamide gels and reacted with antibody to E2F-5. Cells were infected at time zero and harvested at 14 h after infection.

E2F-5 present in mock-infected HEL fibroblasts was present solely in nuclei and also formed two bands. The same two bands were present nuclei of infected cells harvested at 4 and 8 h after infection (Fig. 8, lanes 1 to 5, and 7 to 11). In cells harvested at 12 h after infection, only the slower-migrating isoform was present in detectable amounts. Furthermore, the same isoform was also detected in the cytoplasmic fraction of infected HEL fibroblasts harvested at 12 h after infection (lanes 6 and 12).

FIG. 8.

Immunoblot of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of uninfected or HSV-1(F)-infected serum-starved, contact-inhibited HEL fibroblasts lysates separated on bisacrylamide gels and reacted with antibody to E2F-5. Cells were infected at time zero and harvested at the indicated times after infection.

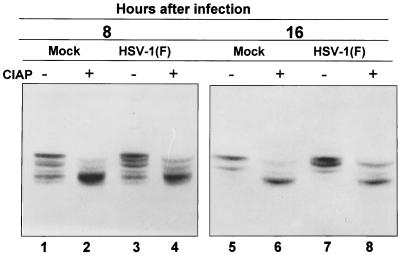

AP treatment of E2F-1 and E2F-4 accumulating in HSV-1-infected cells.

E2F proteins are known to be regulated by phosphorylation. Multiple bands of E2F-1 have been observed by immunoblotting, and these coalesce into a single band following phosphatase treatment of the cell extract (43). E2F-4 has a hyperphosphorylated form that that also migrates faster in denaturing gels after phosphatase treatment (37). The phosphorylated form of E2F-4 is thought to act as a transcriptional repressor. The transition to G1 and S results in a dephosphorylated form that can no longer act as a transcriptional repressor. To determine if HSV-1 infection resulted in the preferential accumulation of specific phosphorylated forms of E2F-1 and E2F-4, two sets of experiments were done.

In the first, nuclear extracts from mock-infected or HSV-1-infected cells were treated with CIAP. Digestion of mock-infected and HSV-1-infected nuclear extracts with CIAP resulted in the accumulation of an E2F-1 that migrated more rapidly than seen in untreated extracts (Fig. 9). Inasmuch as phosphatase inhibitors nullified the effect of CIAP (data not shown), the changes in electrophoretic mobility are due to dephosphorylation rather than proteolytic cleavage of the E2F-1 proteins.

FIG. 9.

Immunoblot of nuclear fractions of uninfected or HSV-1(F)-infected HEp-2 cell lysates treated with or without CIAP, separated on bisacrylamide gels, and reacted with antibody to E2F-1. Cells were infected at time zero and harvested at the indicated times after infection.

Similar experiments were done to determine whether the slower-migrating forms of E2F-4 accumulating in infected cells were posttranslationally modified by phosphorylation. In this experiment, both cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of mock-infected or infected cells were treated with CIAP and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti E2F-4 antibody (Fig. 5). With one exception, CIAP drastically reduced the number and increased the electrophoretic mobility of E2F-4 present in both nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of infected cells (compare lanes 3 and 4, 7 and 8, and 15 and 16). The exception was the E2F-4 contained in the cytoplasmic fraction at 16 h after infection (compare lanes 11 and 12). In this instance, CIAP treatment resulted in a decrease in the electrophoretic mobility of all bands, but these did not acquire the electrophoretic mobility of E2F-4 accumulating in the cytoplasm of uninfected cells. Phosphatase digestion of E2F-4 present in mock-infected cells also led to a increase in electrophoretic mobility and, in the case of nuclear extracts, resulted in the appearance of a second, prominent, slower-migrating band (compare lanes 5 and 6 and lanes 13 and 14). Similar studies on lysates of HEL fibroblasts revealed that the slow-migrating form of E2F-4 present in HSV-1-infected cells was in part phosphorylated (data not shown).

We conclude from the experiments described in this section that E2F-1, E2F-4, and E2F-5 accumulating in infected cells undergo novel posttranslational modifications that differ from those of mock-infected cells. The posttranslational modifications involved primarily phosphorylation inasmuch as after phosphatase digestion, the E2F-4 and E2F-1 proteins contained in extracts of infected-cell nuclei could not be differentiated from those of uninfected cells. This conclusion may not be applicable to E2F-4 contained in cytoplasmic extracts obtained 16 h after infection. In this instance, additional modifications may have taken place.

E2F proteins accumulating in nuclei of infected cells cease to bind to cognate sites on DNA.

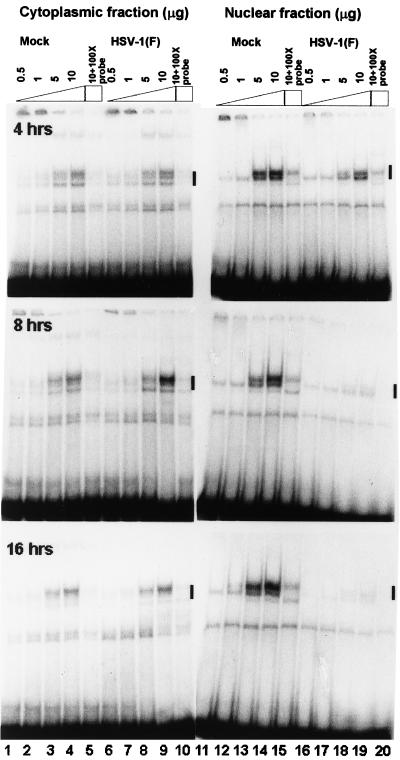

To determine the state of E2F DNA binding activity in HSV-1-infected cells, electrophoretic mobility shift assays were done with labeled DNA fragments containing the E2F consensus binding site and nuclear or cytoplasmic extracts of mock-infected or HSV-1(F)-infected HeLa cells. The results (Fig. 10) were as follows.

FIG. 10.

E2F DNA electrophoretic mobility shift assay of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of uninfected or HSV-1-infected HeLa cell lysates. Cells were infected at time zero and harvested at the indicated times. Increasing amounts of protein extract (0.5, 1, 5, and 10 μg) were reacted with 32P-end-labeled DNA with the E2F consensus binding site. To determine if the gel shift bands were competable, 100-fold excess unlabeled probe was added to 10 mg of each extract (lanes 5, 10, 15, and 20). Bands that were competable are labeled with a dark line.

(i) The cytoplasmic extracts of mock-infected and infected HeLa cells each formed three identical E2F-DNA bands. The formation of the bands was protein extract dose dependent. The bands attained saturation in the presence of 5 μg of protein.

(ii) The nuclear extracts of mock-infected or of 4-h-infected cells each formed two E2F-DNA bands. The bands formed by infected-cell extracts could not be differentiated from those of uninfected cells with respect to electrophoretic mobility, but the total E2F binding DNA in nuclei of infected cells was decreased relative to that of mock-infected cells.

(iii) At 8 h after infection, there was an increase in the amount of the slow-migrating E2F-DNA band formed by cytoplasmic extract of infected cells compared to that of mock-infected cells (Fig. 10). There was little or no change in either amount or electrophoretic mobility of E2F-DNA complexes formed by nuclear extracts of mock-infected cells. In contrast, there was a significant loss of E2F DNA binding activity in nuclei of infected cells compared with those of uninfected cells (Fig. 10, lanes 16 to 19 compared to lanes 11 to 14). Quantification with the aid of the PhosphorImager indicated that at 8 h after infection, the residual DNA binding activity representing less than 15% of the E2F DNA binding activity of mock-infected cells. Also, infected nuclei contained mainly the faster-migrating E2F-DNA complex, with almost complete loss of the slower-migrating complex.

(iv) At 16 h after infection, there was a decrease in the amounts of fast-migrating E2F-DNA complex but no significant difference in the electrophoretic mobility or abundance of the complexes formed by cytoplasmic fractions of mock-infected or infected cells. The E2F DNA complexes formed by nuclear extracts of mock-infected or infected cells could not be differentiated from those formed by corresponding extracts of cells harvested at 8 h after infection.

Identification of the member of the E2F family bound to cognate DNA sequences.

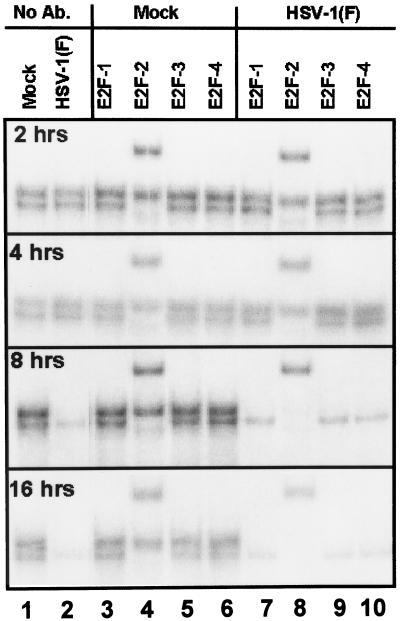

In this series of experiments, mixtures of HEp-2 cell extracts and DNA oligonucleotides containing an E2F binding site described above were reacted with antibody to either E2F-1, E2F-2, E2F-3, or E2F4 and then subjected to electrophoresis on nondenaturing gels as described in Materials and Methods. The results (Fig. 11) were as follows.

FIG. 11.

E2F DNA electrophoretic mobility shift and supershift assays of nuclear fractions of uninfected or HSV-1(F)-infected HEp-2 cell lysates. Cells were infected at time zero and harvested at indicated times; 5 μg of protein extract was subjected to gel shift assay without antibody (Ab.; lanes 1 and 2). Supershift assays were done with the indicated antibodies as described in Materials and Methods (lanes 3 to 10).

(i) Protein-DNA complexes formed by lysates of mock-infected cells harvested at 2, 4, 8, or 16 h after synchronization formed two bands (Fig. 11, lane 1). (ii) The same set of bands were formed by protein-DNA complexes extracted from cells 2 and 4 h after synchronization and infection. Extracts from cells infected for 8 and 16 h formed the fast-migrating but not the slow-migrating band, and the fast-migrating form was reduced in abundance in HSV-infected nuclear extracts compared to mock-infected nuclear extracts (lane 2). (iii) Of the antibodies tested in this experiment, only the antibody against E2F-2 supershifted DNA-protein complexes. Specifically, the antibody shifted the fast-migrating DNA-protein complex derived from extracts of both infected and unnfected cells. The observation that the fast-migrating band disappeared almost entirely concordant with the appearance of the new, supershifted band suggests that that fast-migrating band consisted predominantly of the E2F-2–DNA complex (lanes 3 to 10).

E2F-2 is also the predominant E2F family member in HEL fibroblasts.

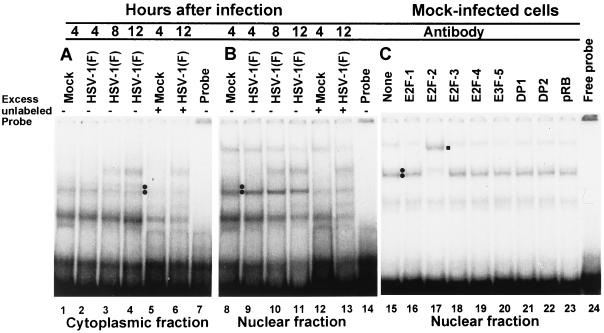

Experiments similar to those described above were also done with extracts of mock-infected or infected quiescent, contact-inhibited HEL fibroblasts. In this instance, the DNA-protein complexes were fainter but more numerous. To identify specific protein-DNA complexes, excess unlabeled DNA was added to mixtures containing probe and extracts from cells harvested at 4 h after mock infection and mixtures containing extracts of cells infected for 12 h after infection. The results were as follows.

(i) Cytoplasmic extracts of mock-infected HEL fibroblasts formed a faint slow-migrating and a slightly more visible fast-migrating DNA-protein complex competed by the addition of excess unlabeled DNA probe (Fig. 12A, compare lanes 1 and 5). The slow-migrating E2F-DNA complex bands formed by cytoplasmic extracts of infected cells (compare lanes 1, 4, and 6) was competed by excess unlabeled probe, whereas as slower-migrating DNA-protein complex could not be competed by excess unlabeled probe. (ii) Nuclear extracts of mock-infected HEL fibroblasts formed a pair of more intense bands (Fig. 12B, lane 8). Of these, the slower-migrating band was not detectable among the bands formed by nuclear extracts of cells harvested at 8 h after infection (lanes 8 to 11). The most prominent band also decreased over the course of infection. (iii) The supershift assays were done on DNA-protein complexes derived from uninfected cells (Fig. 12C). Of the antibodies tested, only anti-E2F-2 caused the quantitative disappearance of the fast-migrating DNA-protein complex an the appearance of a new, supershifted band (lanes 15 and 17).

FIG. 12.

E2F DNA electrophoretic mobility shift assays of cytoplasmic (A) and nuclear (B) fractions of uninfected or HSV-1(F)-infected serum-starved, contact-inhibited HEL fibroblasts lysates. Cells were infected at time zero and harvested at indicated times; 5 μg of protein extract was subjected to gel shift assay. Circles are next to bands specific to either uninfected or HSV-1(F)-infected lysates. Competable gel shift bands were determined by the addition of 100-fold excess unlabeled DNA probe (lanes 5, 6, 12, and 13). Labeled probe without protein extract was loaded in lanes 7 and 14. (C) E2F DNA electrophoretic mobility supershift assays with nuclear lysate of uninfected HEL fibroblast lysates. The square shows the shift upward of a E2F-2–DNA complex.

DISCUSSION

The consensus of the studies carried out in several laboratories and detailed in the introduction is that HSV selectively modifies cell cycle proteins and that in the instances in which this has been critically examined, the modifications are dependent on the presence of specific viral gene products. The studies described in this report are a sequel of studies initiated several years ago and are based on the observation that ICP0 binds and stabilizes cyclin D3 (17). In principle, cyclin D3-cdk4 complex together with the downstream cyclin E-cdk2 should phosphorylate pRB, release the bound members of the E2F family, and activate the S phase of the DNA cycle. At least at times in the viral replicative cycle tested, this does not appear to be the case. Thus, in the mid or late times during the viral replicative cycle, pRB is hypophosphorylated and cdk2 is not activated (7, 34). Consistent with the logical inferences arising from these results, other studies have shown that HSV-1 infection results in the accumulation of heteromeric forms of E2F that in part contain pRb (12). Also, E2F-4 had been shown to accumulate in the nucleus as a hyperphosphorylated form (26). While these studies would suggest that E2F proteins are not released, it has been also shown that E1a and E7 proteins of adenovirus and human papillomavirus, respectively, bind pRB directly and cause the release of E2F (6, 40). Also, a cytomegalovirus-encoded kinase has been shown to directly phosphorylate E2F molecules (27). The studies described in this report focused on the status of the members of the E2F family both in cycling (HEp-2 and HeLa) cells and in quiescent HEL fibroblasts. Our results may be summarized as follows:

(i) E2F-1 was found predominantly in nuclei of mock-infected HeLa or HEp-2 cells. In infected cells, E2F-1 was in part translocated into the cytoplasm, and both the nuclear and cytoplasmic E2F-1 acquired a slower electrophoretic mobility in denaturing polyacrylamide gels. E2F-5 was present solely in the nuclei of infected or mock-infected cells. In this instance, least a fraction of the protein was modified with respect to electrophoretic mobility. For E2F-4, novel hyperphosphorylated forms were found in both the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of infected cells. E2F-2 detected in mock-infected cells could not be differentiated with respect to amounts of electrophoretic mobility from those detected in cells harvested until at least 12 h after infection. At 16 h after infection, there was a decrease in the amounts of detectable E2F-2.

(ii) The studies on infected quiescent, contact-inhibited HEL fibroblasts revealed that members of E2F family were subjected to posttranslational processing or translocation even in the absence of cell cycle progression. The majority of modifications in E2F molecules occurred by 8 h after infection. Thus, a high-molecular-weight E2F-1 species accumulated in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fraction of HEL fibroblasts by 8 h after HSV-1 infection. E2F-2 present in the nuclear fraction also preferentially migrated as a higher-molecular-weight species. E2F-4 forms rearranged from the three predominant forms in uninfected cells to a high-molecular-weight form that was phosphorylated in both the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. Whereas the electrophoretic mobility of E2F-5 remained unaltered, the protein was at least in part translocated into the cytoplasm.

(iii) In G1/S synchronized cycling cells, E2F DNA binding ability increased with time in mock-infected cells. Concurrent with posttranslational modifications described above, we observed a decrease in the affinity of E2F contained in infected cells for cognate DNA sites. Curiously, DNA probe-protein complex formed at least two (Fig. 10) and in some instances three (Fig. 11) bands differing in electrophoretic mobility. All of the bands decreased in amount with time after infection. However, only the antibody to E2F-2 reacted with the proteins contained in these complexes, and in this instance the antibody supershifted the entire DNA-protein complex, indicating that the protein in that complex contained predominantly the E2F-2 member of the E2F family. The possibility that in cultured cells E2F-2 is the predominant E2F species was also suggested by the observation that mock-infected HEL fibroblasts also contained E2F-2 which formed a distinct DNA-protein band (Fig. 12).

The significance of the studies described in this report stem from the following considerations.

(i) Cyclins and cdks are in part responsible for preparing the cellular environment for particular phases of the cell cycle. The G1/S transition is mediated by the sequential activation of cdk4/6 with D-type cyclins followed by cdk2/cyclin E (22). The studies involving the use of cdk inhibitors suggest that they play a crucial role in the transcription of genes early in infection. The stabilization of cyclin D3 by ICP0 is also an early event inasmuch as cyclin D3 persists only 6 to at most 10 h after infection (17, 38).

(ii) The conclusion based on the accumulation of cyclin D3 and its partner, cdk4, and the effects of cdk inhibitors that at least some aspects of S-phase genes are activated and play a role in viral replication is marred by the observation reported elsewhere that cdk2, is not activated and that the status of pRB is inconsistent with activation of the S phase (30). In this study we show that E2F proteins either are extensively modified, are translocated to the cytoplasmic compartment, or become inactive with respect to binding to cognate DNA sites.

(iii) From our knowledge of the events occurring in the course of the viral replicative cycle, the key events that could require the involvement of G0/S-phase cyclins are early transcription of viral gene and viral DNA synthesis. Studies done many years ago indicate that viral DNA synthesis is initiated sometime around 3 h after infection (29). The changes in cell cycle proteins described to date appear to occur in most instances after 4 h after infection. In some instances they are delayed to as long as 12 h after infection.

The fundamental conclusion that must be reached from the studies published to date is that the functions necessary to activate S-phase genes are inoperative at late stages of infection, i.e., at 8 h after infection or later in either cycling or quiescent cells. More specifically, studies done to date do not rule a transient induction of S-phase genes early in infection.

The curious issue that must also be addressed is the events taking place in quiescent, contact-inhibited HEL fibroblasts. The observation that several members of the E2F family were modified or translocated to nonfunctional sites even though the cells were not in S phase at the time of infection is at odds with the hypothesis that the virus evolved functions to block the expression of S-phase genes. The obvious question is why are E2F proteins modified late in infection of quiescent cells. One hypothesis is that E2F proteins transiently performed their natural roles and were then shut off. An alternative hypothesis is that HSV encodes functions that modify members of the E2F family irrespective of the status of the cell cycle. Analyses now in progress on the transcripts of cellular genes made in cells early in infection may ultimately yield the answer to this question.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Renato Brandimarti, Guo-Jie Ye, and Veronica Galvan for invaluable discussions.

This study was aided by Public Health Service grants CA47451, CA71933, and CA78766 from the National Cancer Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Advani S J, Brandimarti R, Weichselbaum R R, Roizman B. The disappearance of cyclins A and B and the increase in activity of the G2/M-phase cellular kinase cdc2 in herpes simplex virus 1-infected cells require expression of the α22/US1.5 and UL13 viral genes. J Virol. 2000;74:8–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black A R, Azizkhan-Clifford J. Regulation of E2F: a family of transcription factors involved in proliferation control. Gene. 1999;237:281–302. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00305-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Bruyn Kops A, Knipe D M. Formation of DNA replication structures in herpes virus-infected cells requires a viral DNA binding protein. Cell. 1988;55:857–868. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeCaprio J A, Ludlow J W, Figge J, Shew J Y, Huang C M, Lee W H, Marsilio E, Paucha E, Livingston D M. SV40 large tumor antigen forms a specific complex with the product of the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene. Cell. 1988;54:275–283. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90559-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeGregori J, Leone G, Miron A, Jakoi L, Nevins J R. Distinct roles for E2F proteins in cell growth control and apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7245–7250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dyson N, Howley P M, Munger K, Harlow E. The human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Science. 1989;243:934–937. doi: 10.1126/science.2537532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehmann G L, McLean T I, Bachenheimer S L. Herpes simplex virus type 1 infection imposes a G1/S block in asynchronously growing cells and prevents G1 entry in quiescent cells. Virology. 2000;267:335–349. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ejercito P, Kieff E D, Roizman B. Characterization of herpes simplex virus strains differing in their effects on social behavior of infected cells. J Gen Virol. 1968;2:357–364. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-2-3-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Field S J, Tsai F Y, Kuo F, Zubiaga A M, Kaelin W G, Jr, Livingston D M, Orkin S H, Greenberg M E. E2F-1 functions in mice to promote apoptosis and suppress proliferation. Cell. 1996;85:549–561. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heibert S W, Chellappan S P, Horowitz J M, Nevins J R. The interaction of Rb with E2F coincides with an inhibition of the transcriptional activity of E2F. Genes Dev. 1992;6:177–185. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helin K. Regulation of cell proliferation by the E2F transcription factors. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:28–35. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hilton M J, Mounghane D, McLean T, Contractor N V, O'Neil J, Carpenter K, Bachenheimer S L. Induction by herpes simplex virus of free and heteromeric forms of E2F transcription factor. Virology. 1995;213:624–638. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hobbs W E, II, DeLuca N A. Perturbation of cell cycle progression and cellular gene expression as a function of herpes simplex virus ICP0. J Virol. 1999;73:8245–8255. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8245-8255.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikeda M, Jakoi L, Nevins J R. A unique role for the Rb protein in controlling E2F accumulation during cell growth and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3215–3220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jordan R, Schang L, Schaffer P A. Transactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early gene expression by virion-associated factors is blocked by an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent protein kinases. J Virol. 1999;73:8843–8847. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8843-8847.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kato J, Matsushime H, Hiebert S W, Ewen M E, Sherr C J. Direct binding of cyclin D to the retinoblastoma gene product (pRb) and pRb phosphorylation by the cyclin D-dependent kinase CDK4. Genes Dev. 1993;7:331–342. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawaguchi Y, Van Sant C, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus 1 alpha regulatory protein ICP0 interacts with and stabilizes the cell cycle regulator cyclin D3. J Virol. 1997;71:7328–7336. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7328-7336.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristie T M, Roizman B. α4, the major regulatory protein of herpes simplex virus type 1, is stably and specifically associated with promoter-regulatory domains of alpha genes and of selected other viral genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:3218–3222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li M, Lee H, Yoon D W, Albrecht J C, Fleckenstein B, Neipel F, Jung J U. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes a functional cyclin. J Virol. 1997;71:1984–1991. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1984-1991.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lomonte P, Everett R D. Herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein Vmw110 inhibits progression of cells through mitosis and from G1 into S phase of the cell cycle. J Virol. 1999;73:9456–9467. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9456-9467.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucas J J, Szepesi A, Modiano J F, Domenico J, Gelfand E W. Regulation of synthesis and activity of the PLSTIRE protein (cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (cdk6)), a major cyclin D-associated cdk4 homologue in normal human T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1995;154:6275–6284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundberg A S, Weinberg R A. Functional inactivation of the retinoblastoma protein requires sequential modification by at least two distinct cyclin-cdk complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:753–761. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margolis M J, Pajovic S, Wong E L, Wade M, Jupp R, Nelson J A, Azizkhan J C. Interaction of the 72-kilodalton human cytomegalovirus IE1 gene product with E2F1 coincides with E2F-dependent activation of dihydrofolate reductase transcription. J Virol. 1995;69:7759–7767. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7759-7767.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller H, Moroni M C, Vigo E, Petersen B O, Bartek J, Helin K. Induction of S-phase entry by E2F transcription factors depends on their nuclear localization. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5508–5520. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicholas J, Cameron K R, Honess R W. Herpesvirus saimiri encodes homologues of G protein-coupled receptors and cyclins. Nature. 1992;355:362–365. doi: 10.1038/355362a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olgiate J, Ehmann G L, Vidyarthi S, Hilton M J, Bachenheimer S L. Herpes simplex virus induces intracellular redistribution of E2F4 and accumulation of E2F pocket protein complexes. Virology. 1999;258:257–270. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pajovic S, Wong E L, Black A R, Azizkhan J C. Identification of a viral kinase that phosphorylates specific E2Fs and pocket proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6459–6464. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roizman B, Sears A E. Herpes simplex viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2231–2295. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roizman B, Roane P R., Jr Multiplication of herpes simplex virus. II. The relation between protein synthesis and the duplication of viral DNA in infected HEp-2 cells. Virology. 1964;22:262–269. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(64)90011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schang L M, Phillips J, Schaffer P A. Requirement for cellular cyclin-dependent kinases in herpes simplex virus replication and transcription. J Virol. 1998;72:5626–5637. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5626-5637.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schang L M, Rosenberg A, Schaffer P A. Transcription of herpes simplex virus immediate-early and early genes is inhibited by roscovitine, an inhibitor specific for cellular cyclin-dependent kinases. J Virol. 1999;73:2161–2172. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2161-2172.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schang L M, Rosenberg A, Schaffer P A. Roscovitine, a specific inhibitor of cellular cyclin-dependent kinases, inhibits herpes simplex virus DNA synthesis in the presence of viral early proteins. J Virol. 2000;74:2107–2020. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.5.2107-2120.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sinclair A J, Palmero I, Peters G, Farrell P J. EBNA-2 and EBNA-LP cooperate to cause G0 to G1 transition during immortalization of resting human B lymphocytes by Epstein-Barr virus. EMBO J. 1994;13:3321–3328. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06634.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song B, Liu J J, Yeh K C, Knipe D M. Herpes simplex virus infection blocks events in the G1 phase of the cell cycle. Virology. 2000;267:326–334. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swanton C, Mann D J, Fleckenstein B, Neipel F, Peters G, Jones N. Herpes viral cyclin/Cdk6 complexes evade inhibition by CDK inhibitor proteins. Nature. 1997;390:164–187. doi: 10.1038/36606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swenson J J, Mauser A E, Kaufmann W K, Kenney S C. The Epstein-Barr virus protein BRLF1 activates S-phase entry through E2F1 induction. J Virol. 1999;73:6540–6550. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6540-6550.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van der Sman J, Thomas N S B, Lam E W F. Modulation of E2F complexes during G0 to S phase transition in human primary B-lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12009–12016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Sant C, Kawaguchi Y, Roizman B. A single amino acid substitution in the cyclin D binding domain of the infected cell protein no. 0 abrogates the neuroinvasiveness of herpes simplex virus without affecting its ability to replicate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8184–8189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verona R, Moberg K, Estes S, Starz M, Verona J P, Lees J A. E2F activity is regulated by cell cycle-dependent changes in subcellular localization. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:7268–7282. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whyte P, Buchkovich K J, Horowitz J M, Friend S H, Raybuck M, Weinberg R A, Harlow E. Association between an oncogene and an anti-oncogene: the adenovirus E1A proteins bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Nature. 1988;334:124–129. doi: 10.1038/334124a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilcock D, Lane D P. Localization of p53, retinoblastoma and host replication proteins at sites of viral replication in herpes-infected cells. Nature. 1991;349:429–431. doi: 10.1038/349429a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamasaki L, Jacks T, Bronson R, Goillot E, Harlow E, Dyson N J. Tumor induction and tissue atrophy in mice lacking E2F-1. Cell. 1996;85:537–548. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81254-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang X H, Sladek T L. Novel phosphorylated forms of E2F-1 transcription factor bind to the retinoblastoma protein in cells overexpressing an E2F-1 cDNA. Biochem Biophy Res Commun. 1997;232:336–339. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]