Abstract

Background:

This study examined the role of depressive symptoms on trajectories of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), cigarette, and cannabis use across 4.5 years in a sample of college students aged 18–19 at the initial study wave.

Methods:

Participants were 2,264 students enrolled in one of 24 Texas colleges that participated in a multi-wave study between 2014 and 2019. Latent growth mixture models were fit to identify longitudinal trajectories for past 30-day ENDS, cigarette, and cannabis use over a 4.5-year period. Class membership was regressed on baseline depressive symptoms in multinomial regression models.

Results:

Four trajectory classes were identified for each product: abstainer/minimal, decreasing, increasing, and high. Depressive symptoms were associated with a greater likelihood of belonging to the decreasing, increasing, and high trajectory classes relative to the abstainer/minimal class for all products, with the exception of the increasing ENDS class and the decreasing cannabis class.

Discussion:

The findings demonstrate that there is considerable similarity across trajectories of ENDS, cigarette, and cannabis use during traditional collegiate years. Furthermore, depressive symptoms increased the likelihood of belonging to substance using trajectory classes for all products.

Keywords: Depressive symptoms, Growth mixture modeling, Nicotine use, Cannabis use

1. Introduction

The role of depression in cigarette smoking and cannabis use has been well studied over several decades (Fluharty et al., 2017; Gorfinkel et al., 2020). The recent emergence of electronic delivery systems (ENDS) presents a new area for exploration between nicotine and depression. Cigarette use has been declining in recent years and is at a historically low point among young adults in contrast to ENDS and cannabis use, which are at historically high levels among young adults (Patrick et al., 2021). Emerging literature indicates that the relationship between depressive symptoms and the use of ENDS products is likely to be similar to the relationship between depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking (Bandiera et al., 2017). However, there are relatively few longitudinal studies of ENDS, cigarette, and cannabis use in the contemporary landscape and fewer have examined the role of depressive symptoms with respect to trajectories of use among young adults. The present study investigates the relationship between depressive symptoms and trajectories of ENDS, cigarette, and cannabis use among participants aged 18 to 19 at the study initiation and 22 to 23 at the study completion.

Patterns of cigarette smoking are established during adolescence and young adulthood, beginning with experimentation, leading to regular use and dependence (National Center for Chronic Disease Control, 2015). These patterns have been characterized by distinct trajectories using analytic techniques such as latent growth mixture modeling (LGMM; Muthén & Muthén, 2000). A recent systematic review of cigarette smoking trajectories that began in adolescence identified the three most common trajectories as low stable, increasing, and other (Ahun et al., 2020). Examining cigarette use trajectories during college years, two patterns consistently emerge: an abstainer/minimal and a high use class (Caldeira et al., 2012; Hair et al., 2017; Lenk et al., 2018). Other trajectories in these studies are more variable. One study reported an increasing and decreasing class (Caldeira et al., 2012); another reported a dabbler class (Hair et al., 2017); and a third reported occasional, decreasing, and late regular classes (Lenk et al., 2018). In studies that examined both cigarettes and cannabis, trajectories for the two substances were similar across adolescence and colligate years. An abstainer and heavy class were consistently present in college-aged individuals (Arria et al., 2016; Caldeira et al., 2012; Jackson et al., 2008, Nelson et al., 2015) and a cannabis only sample (Suerken et al., 2016). In addition, each of these models contained at least one trajectory that could be characterized as increasing and decreasing.

There is little work on longitudinal trajectories of ENDS use in contrast to cigarettes and cannabis use. Moreover, existing research has focused on trajectories of ENDS use in adolescence. Harrell et al. (2021) identified non-users, early escalators, mid escalators, and late escalators in 11–19-year-olds. Park et al. (2020) identified never, low and increasing, and high and increasing trajectories among 13- to 17-year-olds whereas Westling et al. (2017) identified infrequent/no use and accelerated ENDS use trajectories in 14- to 15-year-olds. Lanza et al. (2020) identified non-users, infrequent users, moderate users, young adult-onset frequent users, and adolescent-onset escalating frequent ENDS users in a sample followed from 11th grade to one year past high school. The existing ENDS trajectory literature thus identifies a low/non-user class and an increasing class in each study spanning ages 11 to 20. Understanding ENDS use trajectories in young adulthood, the developmental period in which regular tobacco use and tobacco dependence are typically established (National Center for Chronic Disease Control, 2015), is an important extension of the extant literature.

Depression has been associated with cigarette, cannabis, and ENDS use. A review of adolescent cigarette smoking trajectories indicates that depressive symptoms are consistently associated with problematic cigarette use trajectories (Ahun et al., 2020). Studies that investigated the relationship between depressive symptoms and cannabis trajectories are mixed (Scheier & Griffin, 2021) with some studies reporting no associations with depression (Flory et al., 2004; Windle & Wiesner, 2004) and others reporting depression and cannabis trajectory associations (Brook et al., 2011; Thompson et al., 2018). The emerging literature examining the relationship between ENDS use and depression (Bandiera et al., 2017) suggests similarities with the extensive cigarette literature, though, to date, no studies have examined the role of depressive symptoms in longitudinal trajectories of ENDS use.

The present study seeks to identify longitudinal trajectories of past 30-day ENDS, cigarette, and cannabis use in a sample of college students and to determine the influence of antecedent depressive symptoms in predicting trajectory class membership. We hypothesized that low, high, increasing, and decreasing classes would emerge in each of the ENDS, cigarette, and cannabis use models, the four most common substance use trajectories in the extant literature (Sher et al., 2011). The four patterns have been observed in cigarette and cannabis studies using college-aged samples. With the exception of the decreasing class, these trajectories have been observed in ENDS as well, however, we believe that this exception is because the age range of existing ENDS trajectory models peaks at 20, which is approximately the age at which we would expect a decreasing class to emerge. We also hypothesized that baseline depressive symptoms would be associated with membership in classes exhibiting any substantive substance use relative to the low use class, based on the self-medication model (Gehricke et al., 2007), which indicates that substances such as ENDS, cigarettes, and cannabis, are used to cope with negative affect (Buckner et al., 2007).

2. Material & methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were drawn from the Marketing and Promotions across Colleges in Texas project (Project M-PACT), a sample of 5,482 18- to 29-year-old students at wave one. The wide initial age range precluded using age as the time metric because participants could not contribute to the full age range. We thus used the study wave as the time axis in models but limited the sample to participants under twenty, resulting in a total of 2,264 participants in the present analysis. Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD)/%(n) |

|---|---|

| Baseline depressive symptoms | 7.97 (5.41) |

| Baseline age | 19.03 (0.51) |

| Four-year college | 92.7% (2099) |

| Male | 36.8% (834) |

| Ancestry | |

| European | 31.5% (713) |

| Hispanic | 33.3% (755) |

| African | 7.5% (169) |

| Asian | 20.1% (454) |

| Other | 7.6% (173) |

2.2. Procedure

Project M-PACT is a tobacco use surveillance study that recruited undergraduate students from 24 colleges in five counties surrounding Austin, Dallas/Fort Worth, Houston, and San Antonio. Participants were recruited in fall 2014 and followed until spring 2019. Student email addresses were obtained through open records requests or colleges emailed invitations through colleges’ internal communication channel. See Creamer et al. (2018) for a detailed description of project M-PACT methodology. Possession, sale, and cultivation of cannabis are criminal offenses in Texas. All study participants were of legal age to purchase and use tobacco products during the duration of the study in the above-noted municipalities with the exception of San Antonio where the legal purchase age of tobacco increased to 21 in October 2018. Eligible students were 18–29 years old at wave one, enrolled in college at least part-time, and were degree- or certificate-seeking at a two- or four-year college. Initially, 13,714 students were eligible to participate in the study, of which, 5,482 students (40%) both provided informed consent and completed the initial survey, a rate consistent with typical rates obtained in research using online surveys (Wu et al., 2022). Among the 2,264 participants included in at least one of the models, retention rates ranged from 82.3% (spring 2016) to 69.7% (spring 2019). Online data collection took place every six months between fall 2014 and spring 2017, then annually until spring 2019.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Outcome variables

2.3.1.1. Past 30-Day ENDS Use.

At all eight waves, respondents reported past 30-day ENDS use (i.e., 0 to 30 days) in a manner consistent with nationally representative surveys (e.g., PATH, 2023). Examples of ENDS products were revised throughout the study to reflect the changing landscape of products; initial examples included e-cigarettes, vape pens, and e-hookahs, and the final two waves added JUUL/pod vape and mods. The number of days was log transformed so that log-transformed values ranged from 0 to 3.4.

2.3.1.2. Past 30-Day Cigarette Use.

At all eight waves, respondents reported past 30-day cigarette use. The number of days that cigarettes were used was log-transformed in the same manner described above for ENDS products.

2.3.1.3. Past 30-Day Cannabis Use.

At all eight waves, participants reported how many times they had used marijuana, a question consistent with nationally representative surveys (e.g., Monitoring the Future, 2023). Response options included the following seven choices: 0, 1–2, 3–5, 6–9, 10–19, 20–39, and 40 or more times.

2.3.2. Predictor variables

2.3.2.1. Depressive Symptoms.

The 10 item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression-10 Scale short form (Andresen et al., 1994) assessed depressive symptoms (e.g., depressed affect) at baseline only. Respondents reported the frequency of depressive symptoms within the past week, ranging from 0 “Rarely (<1 Day)” to 3 “Most of the time (5–7 Days).” Two items that pertained to feeling happy or hopeful were reverse coded. The ten items were summed and transformed to z scores.

2.3.2.2. Socio-Demographics..

The following four socio-demographic variables were covariates in models: sex (0 = female/1 = male), race/ethnicity (dummy-coded for Hispanic/Latino, African American, Asian, and other ancestry with European ancestry as the reference category), type of college attended (0 = two-year/1 = four-year), and age. Each of these variables were assessed at baseline.

2.3.2.3. Past 2-week binge drinking.

Participants reported the number of days in the past two weeks on which they had five or more drinks of alcohol in a row, with the following response options: 0, 1 or 2, 3 to 5, 6 to 9, and 10 to 14 days, which were assigned values 0 to 4.

2.4. Analyses

Models for each of the three outcomes were developed in two stages: a) a series of LGMMs that differed only in the number of latent classes were fit to establish trajectory models of ENDS, cigarette, and cannabis use, and b) the latent class memberships established in the first step were regressed on covariates using the three-step maximum likelihood (ML) approach (Bakk et al., 2013; Vermunt, 2010). All models were fit using ML estimation with robust standard errors in Mplus, version 8.6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017), which is an optimal technique for fitting models in the presence of missing data (Graham, 2009). We evaluated the relationship between study retention and the variables included in models by regressing the number of waves that participants contributed to data set on baseline measures of variables. Depressive symptoms were not associated with number of waves; significant negative effects were observed for being male, ENDS, cigarettes, cannabis, and binge drinking; significant positive effects were observed for Asian ancestry (relative to European ancestry) and attending a four-year college. Model R2 values were small effect sizes (Cohen, 1988), with a maximum R2 = .016 (race/ethnicity).

Models for ENDS, cigarettes, and cannabis use were fit using latent variables that represented the model’s intercept, a linear slope, and a quadratic slope. Time was measured in years in which each full unit of time represents one year. The intercept represents the status at the baseline assessment. In each model, parameters were fixed to zero for one class to force a class of participants who abstained or nearly abstained. In addition, random effects were fixed at zero for the linear and quadratic slopes due to convergence issues that precluded systematic model comparisons.

To assess the best number of trajectory classes, we fit a series of models for each outcome that ranged from one to six classes. Models were compared using analytic and theoretical tools to determine the optimal number of trajectory classes. Our initial evaluation of model fit was assessed using plots of the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) to evaluate the rate of decline in BIC values as the number of classes increased. Next, we identified models with potentially redundant trajectories (e.g., two parallel increasing trajectories). Finally, classification accuracy was evaluated using entropy (>.80; Clark & Muthén, 2009) and average within-class probabilities (>.80; Geiser, 2012).

After establishing a LGMM for each of the three products, the class membership from the LGMMs developed in the first stage was regressed on variables using the three-step maximum likelihood (ML) approach. In the first step, trajectory classes were determined as described above. In the second step, a class was estimated for each participant. In the third step, class membership was regressed on independent variables in a multinomial regression model with a correction for classification error. The independent variables were baseline depressive symptoms, binge drinking, and socio-demographic variables, including participant’s biological sex, age at baseline, four- v. two-year college status, and race, coded using dummy variables for African ancestry, Asian ancestry, Hispanic ancestry, and other ancestry.

3. Results

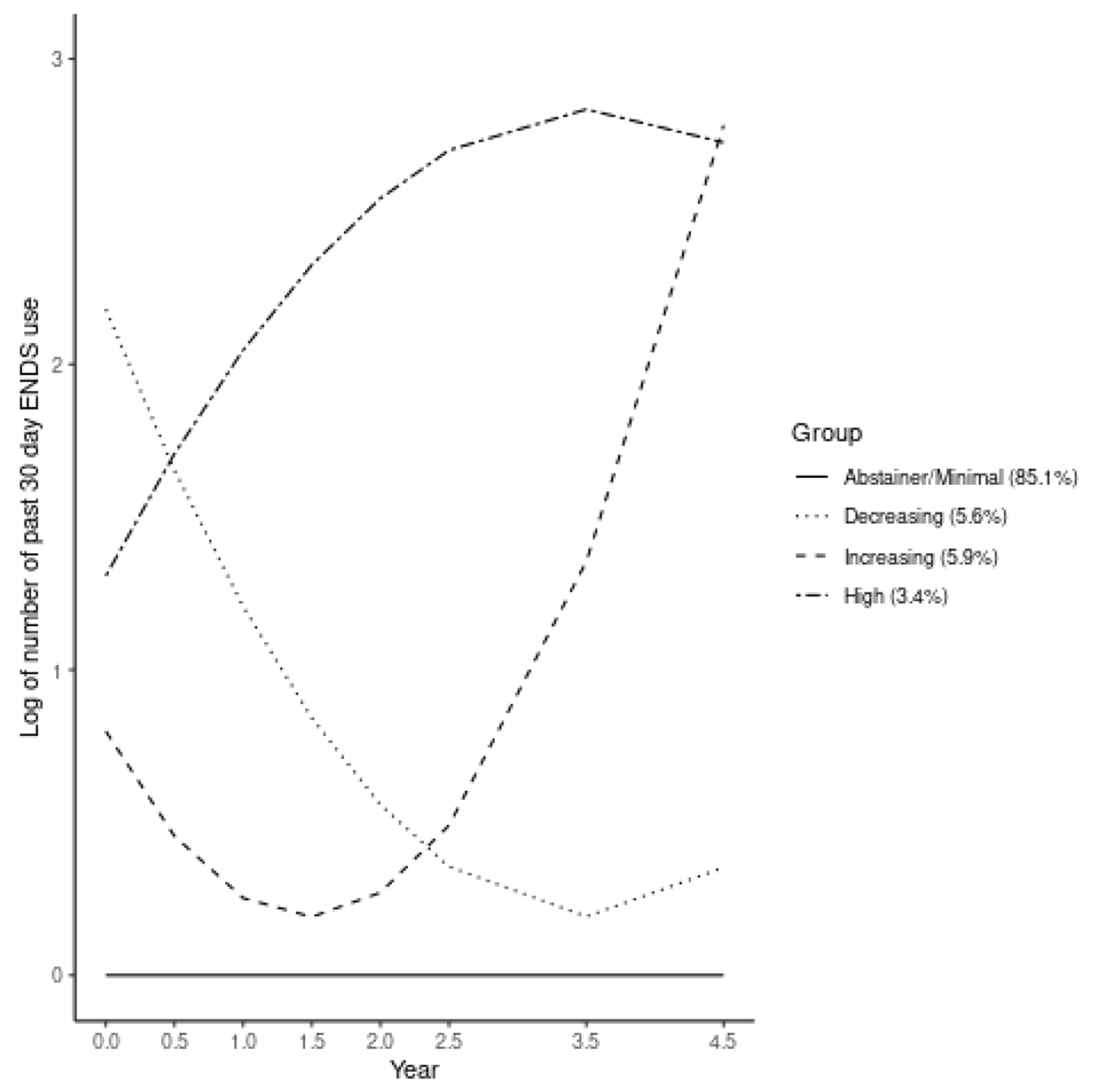

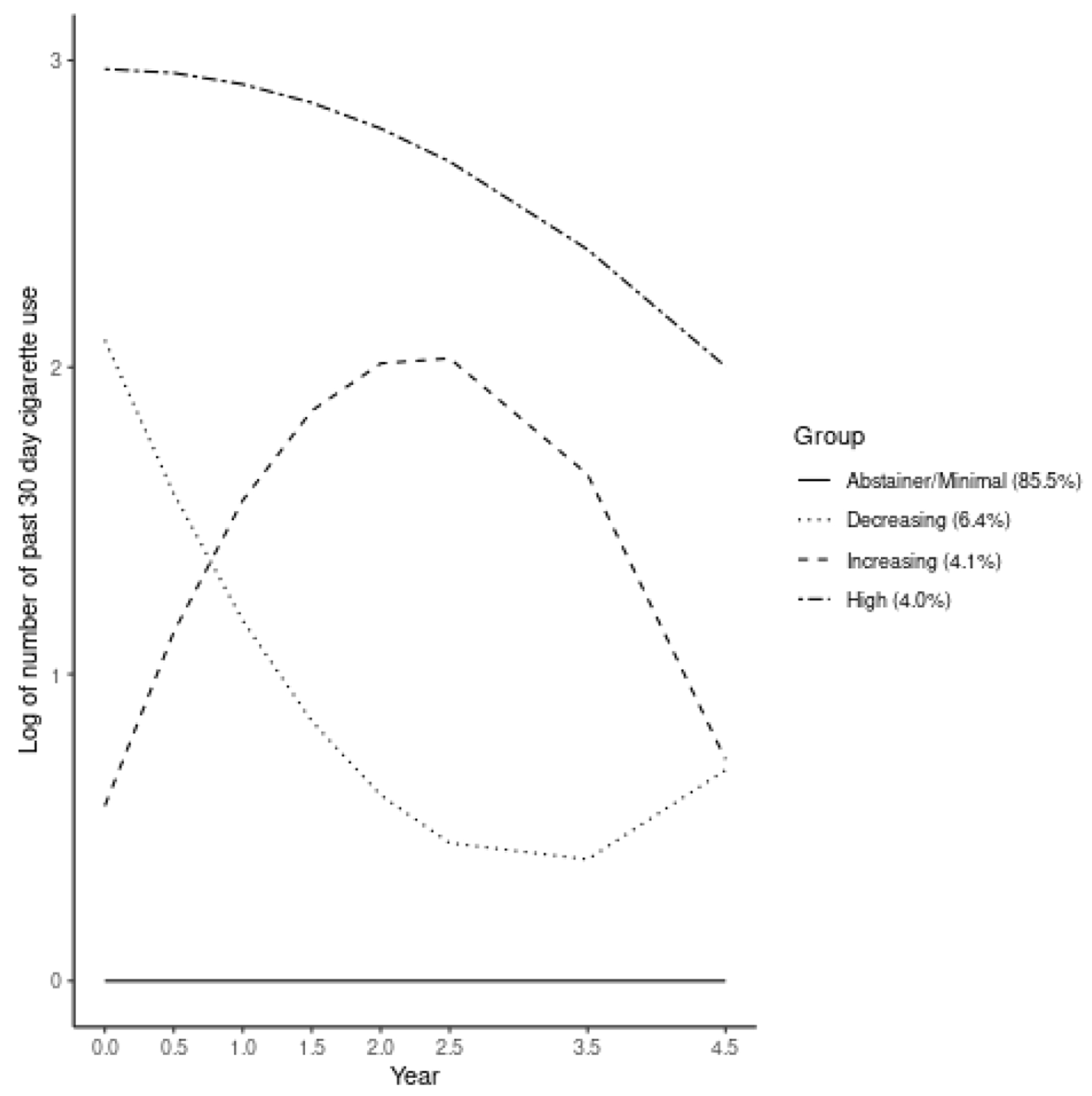

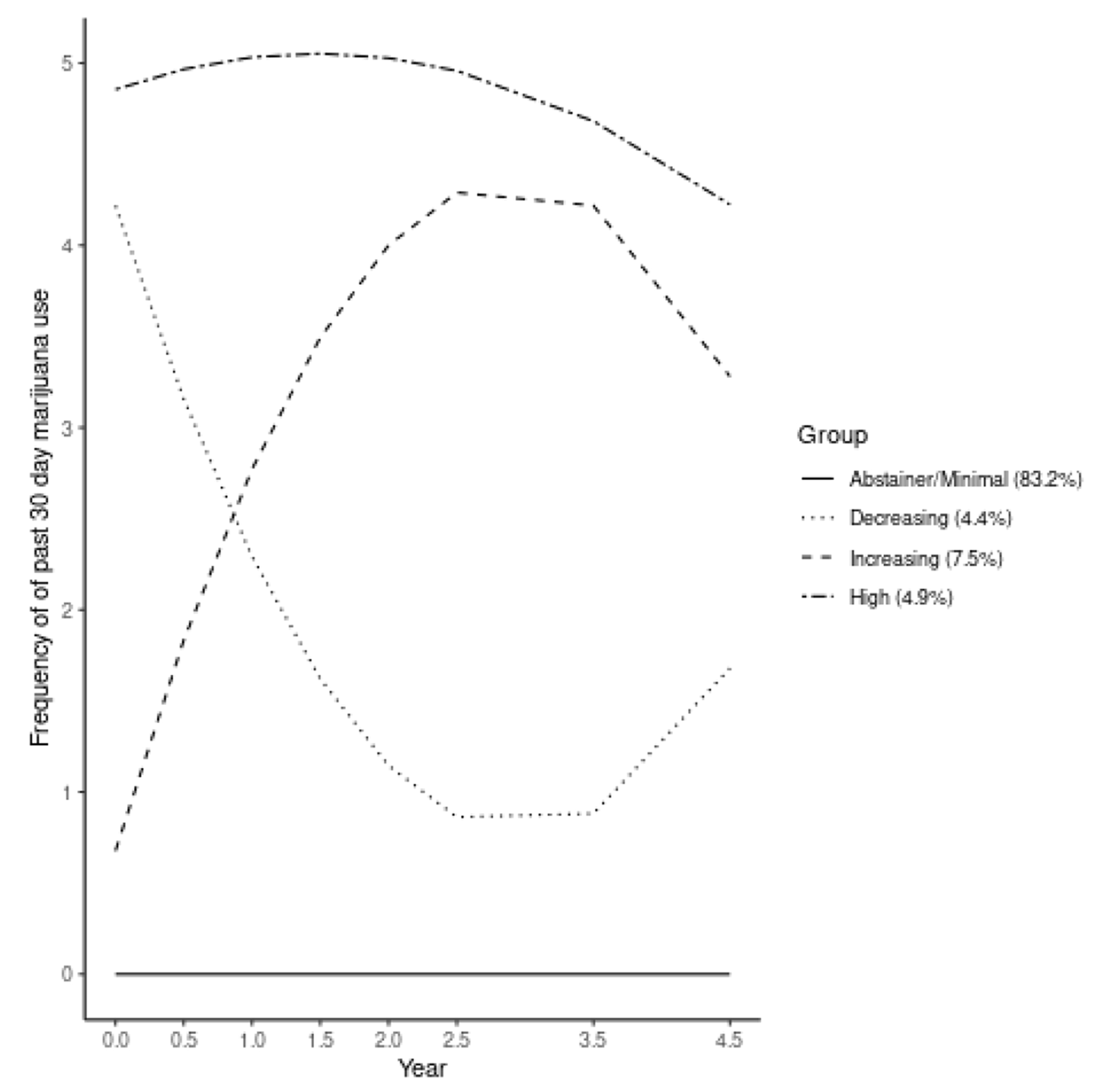

In evaluating our first hypothesis that low, high, increasing, and decreasing classes would emerge in each of the ENDS, cigarette, and cannabis use models, we observed more gradual decreases in BIC values in models with four or more classes. In addition, we favored four-class models given their ubiquity in the substance use latent trajectory model literature (Sher et al., 2011) and because additional classes tended to be redundant with existing classes (e.g., multiple increasing classes). We ultimately selected four-class models for each product. Entropy was excellent for the ENDS, cigarette, and cannabis use models (.96, .98, and .96 respectively) as were average probabilities for most likely latent class membership (.93-.99, .96-.99, and .94-.99 respectively). We characterized the four classes as: abstainer/minimal, decreasing, increasing, and high. As shown in Fig. 1, the abstainer/minimal ENDS class accounted for 85.1% of the sample; the other three classes accounted for 3.4% to 5.9% of the sample. As shown in Fig. 2, the abstainer/minimal cigarette class accounted for 85.5% of the sample; the other three classes accounted for 4.0% to 6.4% of the sample. As shown in Fig. 3, the abstainer/minimal cannabis class accounted for 83.2% of the sample; the other three classes accounted for 4.4% to 7.5% of the sample.

Fig. 1.

Trajectories of ENDS use.

Fig. 2.

Trajectories of cigarette smoking.

Fig. 3.

Trajectories of cannabis use.

While we assigned the hypothesized labels to the classes that they best represented in each model, it is important to note that in spite of the general consistency across the products, there are also important differences. The abstainer/minimal and decreasing trajectories were very similar across the models. The increasing ENDS trajectory exhibited an escalation that accelerated during the final two years of the study in contrast to cigarettes and cannabis that both tapered off after a peak near the two-year point of the study. The high ENDS trajectory escalated across the study in contrast to both the cigarette and cannabis classes that exhibited a mild decrease in use.

Model results that assess our second hypothesis are presented in Table 2: baseline depressive symptoms will predict trajectory classes. Baseline depressive symptoms significantly predicted belonging to the decreasing, increasing, and high trajectory classes relative to the abstainer/minimal class in all models with the exception of the ENDS increasing trajectory and the cannabis decreasing trajectory. Baseline binge drinking was a significant predictor of belonging to decreasing, increasing, and high trajectory classes relative to the abstainer/minimal class for ENDS, cigarettes, and cannabis. Among the socio-demographic variables, males were more likely to belong to the decreasing, increasing, and high trajectory classes than to the abstainer/minimal classes, with the exception of the increasing cannabis trajectory. Asian ancestry, relative to European ancestry, negatively predicted belonging to decreasing, increasing, and high trajectories with the exception of the cigarette decreasing and the ENDS increasing and high trajectories. Hispanic ancestry, relative to European ancestry, predicted decreasing ENDS and cigarette trajectories and negatively predicted increasing and high ENDS trajectories. Participants of African ancestry, relative to participants of European ancestry, were less likely to belong the increasing ENDS trajectory.

Table 2.

Multinomial logistic regression odds ratios of categorical latent variable regressed on covariates using the 3-step procedure from the ENDS, cigarette, and cannabis models.

| Group | Parameter | ENDS OR (95%CI) | Cigarette OR (95%CI) | Cannabis OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreasing | Depressive symptoms | 1.52 (1.25, 1.85) | 1.47 (1.22, 1.76) | 1.20 (0.95, 1.51) |

| Male | 2.22 (1.48, 3.32) | 2.09 (1.42, 3.07) | 2.01 (1.26, 3.21) | |

| Hispanic ancestry | 1.66 (1.01, 2.72) | 1.59 (1.01, 2.50) | 0.74 (0.42, 1.31) | |

| African ancestry | 1.58 (0.71, 3.51) | 0.50 (0.17, 1.51) | 1.38 (0.60, 3.20) | |

| Asian ancestry | 0.37 (0.15, 0.91) | 0.65 (0.35, 1.21) | 0.42 (0.20, 0.88) | |

| Other ancestry | 1.90 (0.88, 4.08) | 1.20 (0.55, 2.62) | 0.60 (0.19, 1.89) | |

| Four-year college | 0.89 (0.45, 1.78) | 1.08 (0.52, 2.25) | 4.52 (0.62, 32.88) | |

| Baseline binge drinking | 2.31 (1.87, 2.85) | 2.65 (2.18, 3.23) | 3.42 (2.69, 4.35) | |

| Increasing | Depressive symptoms | 1.15 (0.94, 1.41) | 1.63 (1.33, 1.99) | 1.52 (1.27, 1.83) |

| Male | 2.00 (1.33, 2.98) | 2.22 (1.42, 3.46) | 1.42 (0.98, 2.06) | |

| Hispanic ancestry | 0.44 (0.26, 0.74) | 0.79 (0.47, 1.33) | 0.97 (0.63, 1.50) | |

| African ancestry | 0.14 (0.02, 0.90) | 0.47 (0.16, 1.39) | 1.59 (0.83, 3.02) | |

| Asian ancestry | 0.58 (0.33, 1.01) | 0.30 (0.13, 0.70) | 0.42 (0.22, 0.79) | |

| Other ancestry | 0.97 (0.47, 1.99) | 1.05 (0.46, 2.41) | 1.20 (0.61, 2.39) | |

| Four-year college | 1.46 (0.55, 3.90) | 1.06 (0.43, 2.58) | 0.70 (0.38, 1.28) | |

| Baseline binge drinking | 1.85 (1.42, 2.41) | 1.85 (1.43, 2.40) | 1.76 (1.35, 2.29) | |

| High | Depressive symptoms | 1.33 (1.05, 1.67) | 1.74 (1.40, 2.16) | 1.47 (1.22, 1.77) |

| Male | 2.94 (1.79, 4.83) | 2.31 (1.47, 3.63) | 2.02 (1.32, 3.08) | |

| Hispanic ancestry | 0.37 (0.19, 0.73) | 0.83 (0.51, 1.37) | 0.76 (0.47, 1.22) | |

| African ancestry | 0.52 (0.17, 1.63) | 0.33 (0.09, 1.18) | 0.48 (0.16, 1.45) | |

| Asian ancestry | 0.53 (0.27, 1.06) | 0.30 (0.14, 0.65) | 0.22 (0.10, 0.52) | |

| Other ancestry | 0.77 (0.29, 2.08) | 0.65 (0.25, 1.68) | 0.68 (0.28, 1.63) | |

| Four-year college | 0.72 (0.29, 1.81) | 1.32 (0.50, 3.51) | 0.88 (0.40, 1.96) | |

| Baseline binge drinking | 1.92 (1.48, 2.49) | 2.24 (1.81, 2.77) | 2.46 (1.98, 3.06) |

Note. For each model, the abstainer/minimal group is the reference group. Thus, odds ratios reflect increased odds of membership in the decreasing, increasing, and high groups relative to the abstainer/minimal group.

4. Discussion

The ENDS use model in a college-aged sample is the primary contribution of the present study, which extends the extant ENDS trajectory literature based on adolescents, aged 11- to 20-year-olds (Harrell et al., 2021; Lanza et al., 2020; Park et al., 2020; Westling et al., 2017) into young adulthood. The four trajectories observed in the present study are common to a wide range of substance use trajectories in young adulthood (Sher et al., 2011). However, the ENDS decreasing trajectory is unique and may reflect a class of college-aged students who ‘mature out’ of ENDS use in young adulthood (Loukas et al., 2019; Waddell et al., 2022).

The ENDS use model showed some key differences from the cigarette and cannabis use models, particularly in the increasing and high ENDS use classes that exhibited increases in the final two years. In contrast, the increasing and high classes in cigarette and cannabis models exhibited tapered use in the final two years, consistent with research indicating that substance use declines as young adults increase in age (Chen et al., 2001). These patterns coincide with a time in which cigarette use is at an all-time low (Patrick et al., 2021), ENDS products are establishing a strong foothold, cannabis legalization is increasing, and both legal and illegal consumption of tobacco and cannabis are increasingly being used in ENDS products. The escalation in the increasing and high ENDS trajectories in 2018 and 2019 coincided with the introduction of vape pods to the market, which could explain increased ENDS usage (Loukas et al., 2022) and decreased cigarettes use as cigarette users transitioned to ENDS products. Additionally, in this time period, cannabis use by college students increased in ENDS products (Hinds et al., 2022).

There are many unique stressors that increase risk for substance use during the traditional colligate years, including the transition from family support systems to independent living, increased academic pressures, and new personal and social challenges (Tosevski et al., 2010). The results of the present study extend the extant literature by demonstrating that depressive symptoms in early collegiate years are associated with long term tobacco and cannabis use patterns (Ahun et al., 2020; Scheier & Griffin, 2021). The stressors associated with this developmental stage potentially increase college students’ vulnerability to depression and substance use, and, combined with increased autonomy, provide an opportunity for self-medication of depressive symptoms with nicotine and cannabis (Fluharty et al., 2017; Weinberger et al., 2017).

The present findings have two important implications for clinical practice and interventions. First, the parallels across the models indicate that existing cigarette interventions are viably applicable to cannabis and ENDS use. For example, meta-analytic findings indicate that the addition of psychosocial mood management to smoking cessation programs increases the programs’ efficacy (van der Meer et al., 2013). Second, assessing nicotine and cannabis use history in clinical applications and interventions establishes a longitudinal pattern that is important for understanding whether users are in an increasing, decreasing, or in steady pattern of use. This information is particularly informative in understanding whether individuals are in an aging-out developmental pattern (Waddell et al., 2022) or potentially on a longer trajectory that would extend tobacco and cannabis use beyond the collegiate years.

The study has limitations that should be considered in evaluating its implications. First, participants were college students in Texas, which limits the generalizability of findings to non-college students and young adults outside of Texas, in particular to states in which cannabis is legal. Second, the primary outcomes measured only past 30-day use, which is a shorter period than the intervals between study waves, leaving substance use quantity unknown for the periods not captured by past 30-day use. Third, the covariates were limited to the baseline assessment in order to ensure that they temporally preceded the outcomes that were discrete trajectory classes that represented the entire time span of the study and thus do not assess time-varying changes in substance use attributable to depressive symptoms.

5. Conclusions

We found that the trajectories of ENDS use across traditional colligate years were similar to trajectories of cigarette and cannabis use. There were low, high, increasing, and decreasing use trajectories for all three substances. Notable differences in the trajectories indicate that increasing and high ENDS trajectories exhibited an uptick in use between 2017 and 2019 in contrast to cigarettes and cannabis that exhibited tapering during that period. Although there was no significant association between depressive symptoms and the increasing ENDS use trajectory, depressive symptoms were predictive of the decreasing and high ENDS trajectories, indicating that established associations between depressive symptoms and cigarette and cannabis use are also present in ENDS users.

Supplementary Material

Role of funding source

Research reported in this publication was supported by a grant [1P50CA180906] from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products and by a grant [R01CA249883] from the NCI. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and thus does not necessarily represent official views of the NCI or the FDA.

Footnotes

Ethical approval

Approval to conduct this research was provided by the University of Texas at Austin institutional review board (protocol no. 2013-06-0034).

Informed consent

All participants provided electronic informed consent before participation.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107809.

Data availability

The data that has been used is confidential.

References

- Ahun MN, Lauzon B, Sylvestre M-P, Bergeron-Caron C, Eltonsy S, & O’Loughlin J (2020). A systematic review of cigarette smoking trajectories in adolescents. International Journal of Drug Policy, 83, Article 102838. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, & Patrick DL (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10, 77–84. 10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Bugbee BA, Vincent KB, & O’Grady KE (2016). Marijuana use trajectories during college predict health outcomes nine years post-matriculation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 159, 158–165. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakk Z, Tekle FB, & Vermunt JK (2013). Estimating the association between latent class membership and external variables using bias-adjusted three-step approaches. Sociological Methodology, 43, 272–311. 10.1177/0081175012470644 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandiera FC, Loukas A, Li X, Wilkinson AV, & Perry CL (2017). Depressive symptoms predict current e-cigarette use among college students in Texas. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19, 1102–1106. 10.1093/ntr/ntx014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Lee JY, Brown EN, Finch SJ, & Brook DW (2011). Developmental trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood: Personality and social role outcomes. Psychological Reports, 108, 339–357. 10.2466/10.18.PR0.108.2.339-357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Keough ME, & Schmidt NB (2007). Problematic alcohol and cannabis use among young adults: The roles of depression and discomfort and distress tolerance. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 1957–1963. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira KM, O’Grady KE, Vincent KB, & Arria AM (2012). Marijuana use trajectories during the post-college transition: Health outcomes in young adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 125, 267–275. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P-H, White HR, & Pandina RJ (2001). Predictors of smoking cessation from adolescence into young adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 26, 517–529. 10.1016/S0306-4603(00)00142-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SL & Muthén BO (2009). Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. http://www.statmodel.com/download/relatinglca.pdf.

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Creamer MR, Loukas A, Clendennen S, Mantey D, Pasch KE, Marti CN, & Perry CL (2018). Longitudinal predictors of cigarette use among students from 24 Texas colleges. Journal of American College Health, 66, 617–624. 10.1080/07448481.2018.1431907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flory K, Lynam D, Milich R, Leukefeld C, & Clayton R (2004). Early adolescent through young adult alcohol and marijuana use trajectories: Early predictors, young adult outcomes, and predictive utility. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 193–213. 10.1017/s0954579404044475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluharty M, Taylor AE, Grabski M, & Munafò MR (2017). The association of cigarette smoking with depression and anxiety: A systematic review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19, 3–13. 10.1093/ntr/ntw140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser C. (2012). Data analysis with Mplus. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Gehricke J-G, Loughlin SE, Whalen CK, Potkin SG, Fallon JH, Jamner LD, Belluzzi JD & Leslie FM (2007). Smoking to self-medicate attentional and emotional dysfunctions. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 9, S523–S536. doi: 10.1080/14622200701685039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorfinkel LR, Stohl M, & Hasin D (2020). Association of depression with past-month cannabis use among US adults aged 20 to 59 years, 2005 to 2016. JAMA Network Open, 3, e2013802–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549–576. 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair E, Bennett M, Williams V, Johnson A, Rath J, Cantrell J, … Vallone D (2017). Progression to established patterns of cigarette smoking among young adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 177, 77–83. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell MB, Chen B, Clendennen SL, Sumbe A, Case KR, Wilkinson AV, … Perry CL (2021). Longitudinal trajectories of E-cigarette use among adolescents: A 5-year, multiple cohort study of vaping with and without marijuana. Preventive Medicine, 150, Article 106670. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds JT, Marti CN, Pasch KE, & Loukas A (2022). Longitudinal trajectories of marijuana use in tobacco products among Texas young adult college students from 2015–2019. Addiction. 10.1111/add.16027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Sher KJ, & Schulenberg JE (2008). Conjoint developmental trajectories of young adult substance use. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32, 723–737. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00643.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza HI, Barrington-Trimis JL, McConnell R, Cho J, Braymiller JL, Krueger EA, & Leventhal AM (2020). Trajectories of nicotine and cannabis vaping and polyuse from adolescence to young adulthood. JAMA Network Open, 3, e2019181–e. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenk KM, Erickson DJ, & Forster JL (2018). Trajectories of cigarette smoking from teens to young adulthood: 2000 to 2013. American Journal of Health Promotion, 32, 1214–1220. 10.1177/0890117117696358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Marti CN, Pasch KE, Harrell MB, Wilkinson AV, & Perry CL (2022). Rising vape pod popularity disrupted declining use of electronic nicotine delivery systems among young adults in Texas, USA from 2014 to 2019. Addiction, 117, 216–223. 10.1111/add.15616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loukas A, Marti CN, & Perry CL (2019). Trajectories of tobacco and nicotine use across young adulthood, Texas, 2014–2017. American Journal of Public Health, 109, 465–471. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring the Future. Monitoring the Future web site https://nida.nih.gov/researchtopics/trends-statistics/monitoring-future. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Muthén BO, & Muthén LK (2000). Integrating person-centered and variablecentered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24, 882–891. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK & Muthén BO (2017). Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Control (2015). The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services Atlanta, GA: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SE, Van Ryzin MJ, & Dishion TJ (2015). Alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use trajectories from age 12 to 24 years: Demographic correlates and young adult substance use problems. Development and Psychopathology, 27, 253–277. 10.1017/S0954579414000650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E, Livingston JA, Wang W, Kwon M, Eiden RD, & Chang Y-P (2020). Adolescent e-cigarette use trajectories and subsequent alcohol and marijuana use. Addictive Behaviors, 103, Article 106213. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, & Bachman JG (2021). Monitoring the Future Panel Study Annual Report: National data on substance use among adults ages 19 to 60, 1976–2021. Retrieved from. https://monitoringthefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/mtfpanelreport2022.pdf.

- Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health web site. https://pathstudyinfo.nih.gov/landing. Accessed May 18, 2023.

- Scheier LM, & Griffin KW (2021). Youth marijuana use: A review of causes and consequences. Current Opinion in Psychology, 38, 11–18. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Jackson KM, & Steinley D (2011). Alcohol use trajectories and the ubiquitous cat’s cradle: Cause for concern? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120, 322–335. 10.1037/a0021813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suerken CK, Reboussin BA, Egan KL, Sutfin EL, Wagoner KG, Spangler J, & Wolfson M (2016). Marijuana use trajectories and academic outcomes among college students. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 162, 137–145. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K, Merrin GJ, Ames ME, & Leadbeater B (2018). Marijuana trajectories in Canadian youth: Associations with substance use and mental health. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 50, 17–28. 10.1037/cbs0000090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tosevski DL, Milovancevic MP, & Gajic SD (2010). Personality and psychopathology of university students. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 23, 48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer RM, Willemsen MC, Smit F, & Cuijpers P (2013). Smoking cessation interventions for smokers with current or past depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10.1002/14651858.CD006102.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18, 450–469. 10.1093/pan/mpq025 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell JT, Jager J, & Chassin L (2022). Maturing out of alcohol and cannabis couse: A test of patterns and personality predictors. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 46, 1603–1615. 10.1111/acer.14898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Kashan RS, Shpigel DM, Esan H, Taha F, Lee CJ, … Goodwin RD (2017). Depression and cigarette smoking behavior: A critical review of population-based studies. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 43, 416–431. 10.3109/00952990.2016.1171327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westling E, Rusby JC, Crowley R, & Light JM (2017). Electronic cigarette use by youth: Prevalence, correlates, and use trajectories from middle to high school. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60, 660–666. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, & Wiesner M (2004). Trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: Predictors and outcomes. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 1007–1027. 10.1017/s0954579404040118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M-J, Zhao K, & Fils-Aime F (2022). Response rates of online surveys in published research: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 7, Article 100206. 10.1016/j.chbr.2022.100206 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.