Allyson Pollock and her colleagues have long argued that using the private finance initiative to build NHS hospitals is an expensive way of building new capacity that constrains services and limits future options. Here they provide evidence that the justification for using private finance—that it offers value for money through lowering costs over the life of the project and by removing risk from NHS trusts—is a sleight of hand

Since 1992 the British government has favoured paying for capital works in the public service through the private finance initiative (PFI)—that is, through loans raised by the private sector. For hospitals this means that a private sector consortium designs, builds, finances, and operates the hospital. In return the NHS trust pays an annual fee to cover both the capital cost, including the cost of borrowing, and maintenance of the hospital and any non-clinical services provided over the 25-35 year life of the contract. The policy has been controversial because of its high cost and impact on clinical budgets.1–6

When first introduced in 1992 proponents claimed that PFI would lead to more investment without increasing the public sector borrowing requirement. However, the UK budget surpluses of recent years (£23bn for 2000-1 alone) have been much greater than the total of £14bn private investment deals signed in 1997-2001. The present generation of taxpayers could have funded considerably more capital investment out of existing revenue instead of displacing the cost on to future generations.7,8

Furthermore, there is no evidence that PFI has increased overall levels of service. On the contrary, its use in the NHS has had two main effects. Firstly, it has displaced the burden of debt from central government to NHS trusts and with it the responsibility for managing spending controls and planning services, thereby hindering a coherent national strategy.9 Secondly, the high cost of PFI schemes has presented NHS trusts with an affordability gap. This has been closed by external subsidies, the diversion of funds from clinical budgets, sales of assets, appeals for charitable donations,10,11 and, crucially, by 30% cuts in bed capacity and 20% reductions in staff in hospitals financed through PFI.2,3 Though NHS funds have increased since 1999, there is no evidence that much has flowed through to baseline services.12

Summary points

The private finance initiative (PFI) brings no new capital investment into public services and is a debt which has to be serviced by future generations

The government's case for using PFI rests on a value for money assessment skewed in favour of private finance

The higher costs of PFI are due to financing costs which would not be incurred under public financing

Many hospital PFI schemes show value for money only after risk transfer, but the large risks said to be transferred are not justified

PFI more than doubles the cost of capital as a percentage of trusts' annual operating income

Thus not only are the macroeconomic arguments in favour of PFI illusory; PFI has also had a negative impact on levels of service. Largely as a result of this, the case for PFI now rests on the “value for money” argument.

The government's claim is that PFI delivers value for money through lowering costs over the life of the project because of greater private sector efficiency and because the private sector assumes the risks that the public sector normally carries. Here we examine the extra costs to NHS trusts of private finance compared with public finance and evaluate the value for money argument with respect to the risks transferred.13

Background

Capital charging regime

Until 1991 all major capital expenditure in the NHS was funded by central government from tax or government borrowing. The NHS did not have to pay interest or repay capital, so in effect new equipment and buildings came “free.” The 1990 NHS and Community Care Act established hospitals as independent business units in the public sector and required them to pay for their use of capital through “capital charges.”

Capital charges are included in the prices charged to purchasers and comprise depreciation, interest, and“dividends”based on the current replacement value of the assets. To pay their interest charges and dividends to the Treasury, trusts must make a surplus, after paying their operating costs and making a charge for depreciation, equal to 6% of the value of their land, buildings, and equipment.

Value for money methodology and risk transfer

The government's procedure for demonstrating value for money is based on an economic appraisal that compares the economic costs and benefits of alternative investment decisions. Using it, the annual costs of a scheme financed by the PFI are summed and compared with those of a notional publicly financed scheme, called the public sector comparator. The methods used contain at least two disputable components: discounting and the costing of risk transfer.

Discounting

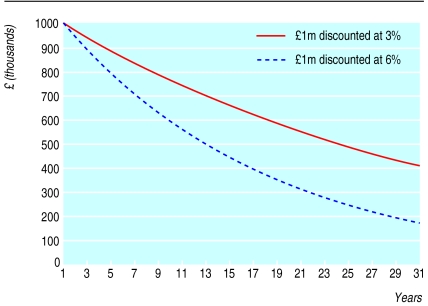

—The government's preferred value for money method states that important economic costs arise from public expenditure and its timing. It is argued that unless public expenditure reflects the market cost of capital it could crowd out more beneficial private investment. This is the cost of capital argument. Secondly, it is argued that the timing of payments is economically significant because people value consumption today over consumption in a year's time or later. This is the time preference argument. Both these economic costs, the cost of capital and time preference, are expressed in a single rate known as the discount rate. By applying a discount rate to future payments a net present cost is obtained. Thus net present cost is not the actual cash cost but a way of expressing as a single value the effect of two hypothetical economic costs.13,14 The net present value or cost is derived by discounting future annual cash costs to reflect the time value of money—the fact that pounds spent in the future are worth less than pounds spent today (see box). This method has implications for the relative costs of the two methods of financing the project. Under conventional public procurement the capital costs are met and accounted for during the construction period, rarely more than three years, and so have relatively higher net “present” value. Under PFI the costs are spread over 30 years and the more distant payments have lower net present value. The discount rate adopted has a crucial impact on whether PFI offers better value than the traditional grant system.2 The Treasury's discount rate is 6% for NHS PFI projects, and welfare economists have repeatedly criticised it as being too high.15

Net present values

What is the rate at which future pounds should be discounted? The figure shows the effect on the net present value in today's prices of £1m spent in each of years 1 to 30 using discount rates of 6% and 3% per year. The higher the discount rate the lower the net present value of payments. With a discount rate of 6%, delaying £1m worth of expenditure to year 10 gives it a net present value of £558 395 and to year 30 one of £174 110. A discount rate of 3% gives £1m expenditure a net present value of £744 109 at year 10 and of £411 987 at year 30.

Risk transfer

—The second element of the value for money methodology is risk transfer. This requires identification of the future pattern of risks and costs over the life of a project for a privately financed hospital compared with a publicly financed hospital. The government claims that the apparently lower cost of publicly financed investment is due to failure to take proper account of the extra costs incurred when things go wrong. Thus a key component of the value for money case is to estimate the cost of the risks transferred to the private sector and to add these costs to the public sector comparator.

The next part of this article identifies the extra costs of using private finance and then examines the two central justifications for these extra costs by evaluating the evidence for and the impact of discounting and risk transfer.

Methods

Comparing cash costs of PFI and public funding values

The cash costs and net present costs of individual PFI hospital schemes and their risk valuations were derived from published data in the House of Commons Health Select Committee Public Expenditure Memorandum (2000, 2001) and from full business cases for individual hospitals.16,17

We could not obtain comparative data on the total cash costs and annual cash flows of the PFI and the public sector comparators before the value for money analysis was made because these data are not available. To understand the costs of the PFI we examined the structure of costs for three PFI schemes: North Durham, Carlisle, and Worcester.

We then examined the impact of the new capital investment on the annual capital costs to NHS trusts, comparing the present capital finance regime (capital charges) with the projected capital charges and payments to the consortia under PFI (known as the annual availability fee). We also tried to estimate what the cost of the new investment would have been if the scheme had been funded out of public capital by applying the 6% capital charge that the Treasury currently requires (see background above) to the total construction costs of the new asset and adding in capital charges on retained estate.

For further schemes we then show the effect on trust operating budgets of new investment financed using the PFI compared with current capital charges.16,17

Value for money analysis

We next examine the value for money case and show the impact of discounting before and after risk transfer on the PFI and public sector comparator for several schemes. We searched unsuccessfully for the methods and evidence base underpinning risk transfer calculations in the hospitals' full business cases and government guidance.

Results

Structure of costs of PFI and public funding

Table 1 shows that for three selected schemes the financing costs—that is, the costs of raising the finance—account for 39% of the total project costs under the PFI. Publicly financed capital does not incur these costs.

Table 1.

Three PFI schemes: extra costs of financing and comparison of annual costs under PFI with those had the scheme been publicly financed and capital charges before PFI

| Worcester (£m) | North Durham (£m) | Carlisle (£m) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure of PFI costs* | |||

| Total capital costs | 112.2 | 86.6 | 83.7 |

| Construction costs and fees | 82.3 | 67.4 | 67.0 |

| Other financing costs | 29.9 (37%) | 18.2 (27%) | 16.7 (25%) |

| Less land sales | 4.5 | NA | NA |

| Total funding needed | 107.7 | 86.6 | 83.7 |

| Annual cost of capital | |||

| Capital charges before PFI | 5.6 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| Annual cost if publicly financed† | 6.8 | 6.4 | 5.9 |

| Annual cost of PFI‡ | 9.3 | 11.3 | 9.0 |

Sources.28-30

Calculated as 6% of construction cost of new hospital plus capital charges on retained estate. Data from Department of Health16 17 and NHS trusts annual accounts.

Calculated as depreciation, public dividend capital, and annual PFI availability charge.16 17

Annual cost of capital—

Table 1 shows the effect of new investment on the capital charges trusts have to pay from their revenue budgets using PFI and an estimate of the costs that would be incurred using public finance for a scheme with similar construction costs. In both cases the annual cost of capital rises steeply but is more marked for PFI. The PFI costs are almost double the estimated costs of a similar scheme funded by public finance.

Annual revenue costs—

Table 2 shows for eight trusts the capital costs under PFI as a percentage of each hospital's current revenue in the first year of its operation, when private finance is used compared with the capital charges currently using public finance. In all cases, the annual cost of capital is higher under PFI. (Table A on bmj.com gives the same data for a further 12 trusts.)

Table 2.

Annual revenue implications of capital costs for eight PFI schemes comparing costs before and in the first year of the PFI scheme

| Trust | Before PFI (capital charge as % of revenue 1998-9) | After PFI (capital charges+availability fee as % of projected revenue in 1st year of operations) |

|---|---|---|

| Hereford Hospitals | 3.8 | 14.6 |

| South Tees | 5.6 | 13.1 |

| Dartford and Gravesham | 6.7 | 32.7 |

| Greenwich Healthcare | 2.1 | 16.2 |

| Swindon and Marlborough | 3.8 | 16.4 |

| Bromley Hospitals | 7.0 | 10.7 |

| Calderdale Healthcare | 3.4 | 13.1 |

| North Durham Healthcare | 4.2 | 12.2 |

Refers to 1999-2000. All calculations include payments to Treasury on existing and retained estate.

Data from Department of Health.16 17

Risk and the value for money analysis

The impact of risk and discounting on the VFM analysis

—Table 3 shows for six hospitals that the net present value of the public sector comparator was lower than that of the PFI option, even after applying a 6% discount rate (table B on bmj.com shows the same data for a further five trusts). Only after risk transfer was included was the net present value of PFI less than the public sector comparator. Also, after risk transfer, the difference between the PFI and the public sector comparator in all cases is marginal—for example, 0.05% at Swindon and Marlborough.

Table 3.

Comparison of discounted costs of new hospitals under public and private finance before and after risk transfer (net present values)

| Trust | Public finance (£m) | PFI (£m) | % Difference between public and private finance (£m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swindon and Marlborough | |||

| NPV | 1246.7 | 1263.3 | |

| Risk adjusted | 1311.3 | 1310.6 | 0.05 |

| Value of risk | 64.6 | 47.3 | |

| Risk as % of total capital costs to private sector | 16.5% | ||

| Kings Healthcare | |||

| NPV | 2935.4 | 2958.3 | |

| Risk adjusted | 2960.1 | 2959.2 | 0.03 |

| Value of risk | 24.7 | 0.9 | |

| Risk as % of total capital costs to private sector | 37.2% | ||

| St George's Healthcare | |||

| NPV | 552.4 | 564.3 | |

| Risk adjusted | 566.0 | 565.4 | 0.11 |

| Value of risk | 13.6 | 1.1 | |

| Risk as % of total capital costs to private sector | 31.3% | ||

| South Durham | |||

| NPV | 665.3 | 671.4 | |

| Risk adjusted | 674.8 | 671.8 | 0.44 |

| Value of risk | 9.5 | 0.4 | |

| Risk as % of total capital costs to private sector | 19.0% | ||

| Hereford Hospitals | |||

| NPV | 665.9 | 680.3 | |

| Risk adjusted | 692.6 | 685.1 | 1.08 |

| Value of risk | 26.7 | 4.8 | |

| Risk as % of total capital costs to private sector | 34.2% | ||

| South Tees | |||

| NPV | 201.7 | 230.5 | |

| Risk adjusted | 271.6 | 232.3 | 14.47 |

| Value of risk | 69.9 | 1.8 | |

| Risk as % of total capital costs to private sector | 50.4% |

NPV=Net present value.

Data from Department of Health.16 17

Risk as a proportion of total capital costs

—Tables 3 and B also show that the private sector's risk as a proportion of the total capital costs under PFI varies enormously between projects—from 17.4% in Swindon and Marlborough to 50.4% at South Tees.

The contribution of risk to costs

—Table 4 shows that the value of risk transferred to the private sector is remarkably close to the amount needed to close the gap between the public sector comparator and the PFI (a further four trusts are listed in table C on bmj.com).

Table 4.

How risk transfer closes the gap between the net present costs of a publicly funded scheme and those of a PFI scheme

| Trust | Cost advantage to publicly financed scheme before risk transfer (£m) | Value of risk transfer to the PFI scheme |

|---|---|---|

| Swindon and Marlborough | 16.6 | 17.3 |

| Kings Healthcare | 22.9 | 23.8 |

| St George's Healthcare | 11.9 | 12.5 |

| South Durham | 6.1 | 9.1 |

| Hereford Hospitals | 14.4 | 21.9 |

| South Tees | 28.8 | 67.8 |

Data from Department of Health.16 17

Discussion

The two most commonly asked questions about the use of PFI are, firstly, how the costs of private finance and public funding of capital projects compare and, secondly, what would be the annual revenue cost to the NHS trust if the scheme were publicly funded. The data required to answer these questions have not been made publicly available, but our best estimates are that the costs of private finance are higher and that trusts pay much more than they would if the new buildings had been publicly funded.

The higher costs of PFI

The high costs of using PFI are due in part to financing costs that a public sector alternative would not incur. The costs of raising finance at North Durham, Carlisle, and Worcester added an average of 39% to the total capital costs of the schemes. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, private debt always costs more than public debt. Secondly, the amount of capital to be raised through loans or equity under PFI is inflated by financing charges such as professional fees and the “rolled up interest” due during the construction period when the PFI consortium is not yet receiving any payments from the NHS trust. In addition there are fees for preparing the PFI bid and contract negotiations, which are not always identified in advance. For example, NHS Estates showed that the Carlisle proposal did not identify any costs “prior to the date of the signature of the agreement, unlike the [public sector comparator] where the trust has identified a cost associated with the preparation of the business case.”18

Although new PFI hospitals replace two or three hospitals with one, are sited on less expensive out of town sites, have fewer beds, and use the proceeds of land sales and Treasury subsidies, they are still not revenue neutral. The cost of private capital as a percentage of trusts' annual revenue expenditure rises from an average of 8% to 27%. Without a concomitant increase in revenue, local services will struggle. In school PFIs local authorities receive an annual PFI credit from central government over and above their standard spending assessment19 to pay for the capital costs of PFI. In contrast NHS trusts are expected to find the extra money from their own resources. Treasury policy is that there are still efficiency savings to be made in the NHS.

But, as table 1 shows, the switch in 1991 from government grant to debt finance means that all new investment, whether publicly or privately financed, increases the cost of capital to NHS trusts and translates into new revenue pressures. This explains why scarce NHS capital budgets are underspent, the backlog in maintenance and repairs has been rising, trusts have merged to dispose of estate, and 13 000 NHS beds have closed since 1997.20

Justifying the higher costs of private finance

The value for money analysis seems to be no more than a mechanism that has been created to make the case for using private finance. Even with a high discount rate (which favours PFI), PFI costs are still higher than those of the public sector comparator. So the value for money claims rest on risk transfer.

As table 3 shows, in all schemes risk transfer is the critical element in proving the value for money case. There is considerable variation between schemes in the absolute and relative value of risk transferred. What is striking, however, is that in all cases risk transfer almost equals the amount required to bridge the gap between the public sector comparator and the PFI. This suggests that the function of risk transfer is to disguise the true costs of PFI and to close the difference between private finance and the much lower costs of conventional public procurement and private finance.

Even after this manipulation, however, the difference between the public sector comparator and the PFI is marginal, in many cases less than 0.1%. Not only does this raise questions about the reliability and validity of the methods used, but it also raises serious questions about why the government is using an unevaluated method of procurement for critically important services.

The evidence for the risk assessment method

Risk is the most difficult and contentious part of the value for money methodology. The argument is that by getting the private sector consortium to bear some of the risks associated with the construction of the hospital and its subsequent management, a trust enjoys greater value for money than under a publicly financed alternative, where the trust would bear all the risks. There are three points to note.

Firstly, the Treasury's policy on risk transfer is that risk should be held by the party best able to control it. Contract theory, however, holds that risk is best managed when held by the party best able to bear it. The state is better able to bear the risks than the private sector.21

Secondly, risk transfer requires the ability to quantify the probability of things going wrong. There is no standard method for identifying and measuring the values of risk, and the government has not published the methods it uses. The business cases we examined do not reveal how the risks were identified and costed. Our findings are supported by a Treasury commissioned report which found that in over two thirds of the business cases for hospital PFI schemes the risk could not be identified. In the other cases risk transfer was largely attributed to construction cost risks, which would be dealt with by penalty clauses under traditional procurement contracts.22

Thirdly, risks can be transferred only through a contract that identifies them. Yet there is reason to cast doubt on the claim that contracts offer a means of transferring financial risk.23 Where a trust wishes to terminate a contract, either because of poor performance or insolvency of the private consortium, it still has to pay the consortium's financing costs, even though the latter is in default. It would otherwise have to take over the consortium's debts and liabilities, given that the lending institutions make their loans to the consortiums conditional on NHS guarantees. In such cases “the attempt to shift financial responsibility from the public to the private sector fails. De facto, a risk-sharing arrangement results from force majeure,” as the Railtrack collapse has shown.24

And risk transfer can never cover all risks. For example, at Darent Valley Hospital in Dartford and Gravesham nurses complained that the design was not conducive to effective care, and equipment was not working properly when the hospital first opened.25 At the new Princess Margaret Hospital in Swindon the recovery room is located 80 metres from the operating theatre. It is unclear how trusts can be compensated for such poor design.

The high value of risk transfer—up to 50% of the total capital cost to the private sector (table 4)—indicates the high levels of compensation being paid to the private sector for risk transfer. Yet external evidence questions the basis for such high valuations of risk. In several PFI projects the consortiums have refinanced their loans at a lower cost because the risks turned out to be less than expected—but the public sector is still paying the cost of the initial financing. PFI consortia have even advertised that their projects contain “little inherent risk” and have been able to issue bonds with a triple A rating, which indicates low risk. Finally, at least one construction company (Jarvis) has sold off its construction arm in order to concentrate on PFI projects, which it says are less risky than conventional construction projects.

What really happens to the risk

Two failed PFI schemes in Australia contain important evidence on risk transfer.26 The Victoria government had to buy back La Trobe Hospital from Australian Hospital Care in October 2000, because “the losses incurred by AHP on the contract meant it could no longer guarantee the hospital's standard of care.” At Modbury Hospital the South Australian government had to come to the rescue of the contractor and increase its contractual payments or the contractor would have defaulted. Closer to home, the Benefits Agency and Passport Office fiascos, and other failed private finance schemes, show that ultimately the risk is not transferred—the taxpayer ends up paying for private sector risks.27

But irrespective of whether and how much financial risk is actually transferred and to whom, the main risks are those that arise from technical obsolescence, changing regulation, and unmet patient needs, risks which ultimately the NHS, local communities, and patients will have to bear. Should conditions change during a 30 year contract, rendering the facilities unsuitable, the NHS will find itself locked into long term contracts and payments and patients may find they have to go without care.

Supplementary Material

Figure.

KENTISH TIMES

Darent Valley Hospital: nurses complained the design was not conducive to effective care

Footnotes

Three tables with data for more trusts appear on bmj.com

References

- 1.Gaffney D, Pollock AM, Price D, Shaoul J. NHS capital expenditure and the private finance initiative: expansion or contraction? BMJ. 1999;319:48–51. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7201.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaffney D, Pollock AM, Price D, Shaoul J. PFI in the NHS: is there an economic case? BMJ. 1999;319:116–119. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7202.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollock AM, Dunnigan M, Gaffney D, Price D, Shaoul J. Planning the new NHS: downsizing for the 21st century. BMJ. 1999;319:179–184. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7203.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaffney D, Pollock AM, Price D, Shaoul J. The private finance initiative: The politics of the private finance initiative and the new NHS. BMJ. 1999;319:249–253. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7204.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawksworth J. The private finance initiative: saviour, villain or irrelevance? London: Institute of Public Policy Research; 2000. Implications of the public sector financial control framework for PPPs. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heald D, Scott D. Lessons from capital charging in the UK national health service. Int Assoc Management J. 1996;8:29–45. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Accounting Standards Board. Amendment to FRS5: reporting the substance of transactions: Private Finance Initiative and similar contracts. London: Accounting Standards Board; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broadbent J, Haslam C, Laughlin R. The origins and operation of the private finance initiative. In: Robinson P, editor. The PFI: saviour, villain or irrelevance? London: IPPR; 2000. pp. 26–47. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollock AM, Dunnigan M, Gaffney D, Macfarlane A, Majeed FA. What happens when the private sector plans hospital services for the NHS: three case studies under the private finance initiative. BMJ. 1997;314:1266–1271. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7089.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norfolk and Norwich Healthcare Trust. Final business case. Norwich: NNHT; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 11.University College London Hospitals. Final business case. London: UCLH; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Browne A. Why the NHS is bad for us. Observer 2001;7 Oct. www.observer.co.uk/comment/story/0,6903,564801,00.html.

- 13.Sussex J. The economics of the private finance initiative in the NHS. London: Office of Health Economics; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.HM Treasury. Appraisal and evaluation in central government [Green book]. 2nd ed. London: HMSO; 1997. :chap 4, appendix G. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearce DW, Ulph D. A social discount rate for the United Kingdom. Norwich: Centre for Social and Economic Research on the Global Environment; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health. Expenditure questionnaire 2000. Memorandum to the Health Committee, NHS resources and activity. London: Stationery Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Health. Memorandum to the Health Committee: Public Expenditure Questionnaire 2001. London: Stationery Office; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carlisle Hospitals FBC, Appendices Volume 1, Appendix G, paragraph 8.1.e.

- 19.Rowland D, Pollock AM, Price D. The school governors' essential guide to PFI. London: Unison; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Department of Health. Bed availability and occupancy 2000-2001. www.doh.gov.uk/hospitalactivity.

- 21.Ulph D. Contract theory and the public private partnership proposals for the London Underground railway system. London: Industrial Society; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arthur Andersen and Enterprise LSE. Value for money drivers in the private finance initiative. www.ogc.gov.uk/pfi/series_1/andersen/7tech_contents.html.

- 23.Pollock AM. Will primary care trusts lead to US-style health care. BMJ. 2001;322:964–967. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7292.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollock AM, Shaoul J, Rowland D, Player S. Public services and the private sector: a response to the IPPR Commission. London: Catalyst, November; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hellowell M. Problems at Darent Valley Hospital. The PFI Report 2000; Sept:45:9.

- 26.Senate Community Affairs References Committee. Healing our hospitals. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pollock AM, Vickers N. Private pie in the sky. Public Finance 14 April 2000;22-3.

- 28.Pollock AM, Price D, Dunnigan M. Deficits before patients. London: UCL; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaffney D, Pollock A. Downsizing for 21 st century. London: Unison; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price D, Gaffney D, Pollock A. The only game in town? A report of the Cumberland Infirmary. London: Unison; 1999. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.