Abstract

Background

Advanced practice providers (APPs), including physician assistants/associates (PAs), nurse practitioners (NPs) and other non-physician roles, have been developed largely to meet changing healthcare demand and increasing workforce shortages. First introduced in primary care in the US, APPs are prevalent in secondary care across different specialty areas in different countries around the world. In this scoping review, we aimed to summarise the factors influencing the development, recruitment, integration, retention and career development of APP roles in hospital health care teams.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review and searched Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Ovid Global Health, Ovid PsycINFO and EBSCOhost CINAHL to obtain relevant articles published between Jan 2000 and Apr 2023 that focused on workforce management of APP roles in secondary care. Articles were screened by two reviewers independently. Data from included articles were charted and coded iteratively to summarise factors influencing APP development, recruitment, integration, retention and career development across different health system structural levels (macro-, meso- and micro-level).

Results

We identified and analysed 273 articles that originated mostly from high-income countries, e.g. the US (n = 115) and the UK (n = 52), and primarily focused on NP (n = 183) and PA (n = 41). At the macro-level, broader workforce supply, national/regional workforce policies such as work-hour restrictions on physicians, APP scope of practice regulations, and views of external collaborators, stakeholders and public representation of APPs influenced organisations’ decisions on developing and managing APP roles. At the meso-level, organisational and departmental characteristics, organisational planning, strategy and policy, availability of resources, local experiences and evidence as well as views and perceptions of local organisational leaders, champions and other departments influenced all stages of APP role management. Lastly at the micro-level, individual APPs’ backgrounds and characteristics, clinical team members’ perceptions, understanding and relationship with APP roles, and patient perceptions and preferences also influenced how APPs are developed, integrated and retained.

Conclusions

We summarised a wide range of factors influencing APP role development and management in secondary care teams. We highlighted the importance for organisations to develop context-specific workforce solutions and strategies with long-term investment, significant resource input and transparent processes to tackle evolving healthcare challenges.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12916-024-03509-6.

Keywords: Secondary care, Extended roles, Additional roles, Physician assistant/associate, Nurse practitioner, Employee management, Teamwork

Background

Increasing demand, growing complexity of healthcare and workforce shortages have led hospitals and healthcare organisations to consider innovative service models and new clinical roles [1, 2]. Advanced practice providers (APPs), including physician assistants/associates (PAs), nurse practitioners (NPs) and other non-physician roles, is a term that has been used for coding and billing purposes by the US Medicare and Medicaid [3]; however, we acknowledge that this term might not be accepted or preferred by all PA and NP professions but use it for convenience here. APPs have a long history, dating back as early as the nineteenth century in low- and middle-income countries [4]. They later emerged in the US in the 1960s and subsequently in many countries of various stages of development [5, 6]. Now PAs exist in over 62 countries under different practice titles [7], and an estimated 40 countries have well-established NP roles [8]. Both PA and NP roles were first introduced in primary care in the US to address the shortage of primary care physicians, but their roles have evolved and they are now more prevalent in secondary care and across different specialty areas [9, 10]. Despite variable job role titles, APPs often have considerable overlap in their scope of practice, often including providing clinical leadership and enabling collaborations in multi-professional teams [11, 12].

Previous systematic reviews have provided evidence on the role and contribution of APPs in hospital health care teams, including reduced waiting and processing time, improved patient continuity and satisfaction, similar clinical safety and patient outcomes, and possibly contained cost and enhanced educational experiences of other trainees [13–19]. There has been less focus on understanding why and how health systems and hospitals develop APP roles as well as how to best integrate and retain them. This is especially important as reconfiguring the workforce and introducing new roles will often lead to professional jurisdiction and boundary tensions, impacting early role development and integration [20]. Additionally, less well-defined career progression pathways beyond entry-level especially for roles like PA [21] could lead to poor retention, worsening workforce shortages and avoidable turnover costs.

In this scoping review, we aim to summarise the factors associated with the development, recruitment, integration, retention and career development of APP roles in secondary care teams. This review can inform regulators, hospital managers and policy-makers on factors to consider while using APPs to address hospital workforce challenges. This is especially important for countries like the UK where the development of PA roles is relatively new and hospitals face significant challenges integrating PA into the workforce with confusion over and contestation around roles.

Methods

We followed the five steps of Arksey and O’Malley method [22] for scoping reviews to capture a broad range of research evidence from the academic literature. Our research question is ‘what influenced the development, recruitment, integration, retention and career development of APPs into secondary care teams?’

Search strategy and screening

In consultation with an experienced librarian, we conducted a systematic search using Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, Ovid Global Health, Ovid PsycINFO and EBSCOhost CINAHL to obtain relevant articles. We included all kinds of study designs as well as case reports published between Jan 2000 and Apr 2023. We combined keyword terms and phrases related to NP, PA, workforce, secondary and hospital care (see Additional file 1 for an example search strategy). We are interested in roles like PAs, NPs and equivalent professions in other countries (clinical officers, assistant medical officers, surgical care practitioners, anaesthesia assistants, etc.) where the primary aim is to share work with doctors formally. We included articles if they examined any aspect of role development, recruitment, integration, retention and career development (see Table 1 for definitions for each focus) of APPs in secondary care and above, including hospital-based ambulatory care. We excluded articles that primarily focus on primary care and community health or were not empirical work.

Table 1.

Definitions used for the scoping review

| • Focus—we are interested in the following aspects of workforce management: |

| o Development refers to when organisations start a completely new role |

| o Recruitment refers to when organisations identify, attract, interview, select and hire new workers |

| o Integration refers to enabling workers to understand each other’s roles and contributions, and building support networks around individuals and their community [23]. We include the onboarding and orientation process as part of the integration |

| o Retention refers to keeping and continue employing existing workers |

| o Career development refers to enabling individual workers’ professional growth |

| • Roles—we recognise different APP roles have different titles; in this review, we have grouped the articles into the following categories: |

| o Physician associates (PA) including physician assistants |

| o Nurse practitioners (NP) including advanced nurses, nurse specialists and nurse consultants |

| o Clinical officers commonly seen in low- and middle-income countries |

| o Others including anaesthesia associates and surgical care practitioners |

| • Levels—we summarise findings across different health system structural levels: |

| o Macro-level refers to system-wide issues and those external to the organisation |

| o Meso-level refers to organisational and departmental issues |

| o Micro-level refers to individual and interpersonal issues |

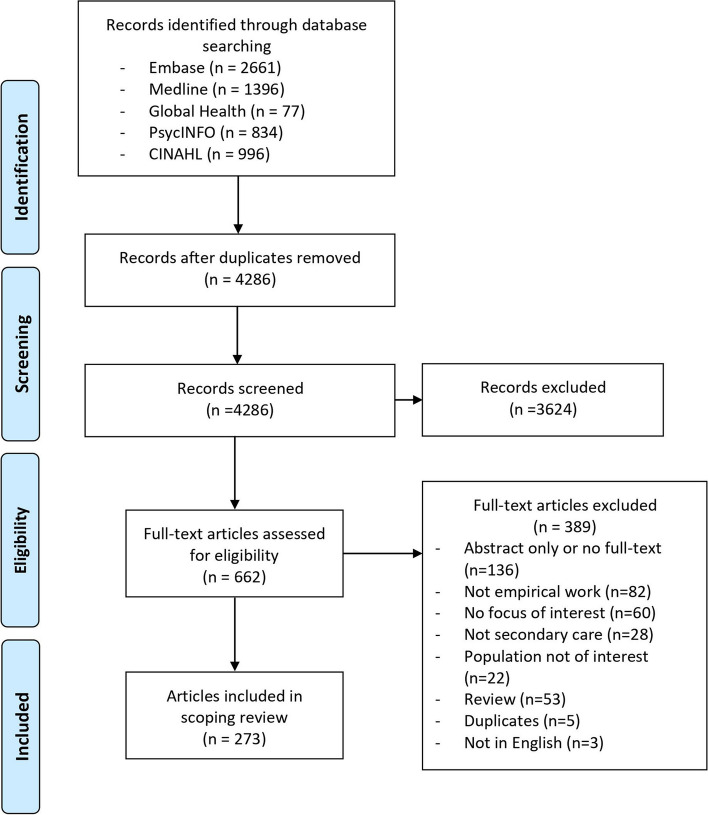

After deduplication, we imported the citations into an online screening tool (Abstrackr) for the initial title and abstract screening [24]. Two reviewers were involved in the title and abstract, and full-text screening. YZ reviewed all the titles and abstracts to assess eligibility for full-text review, and a random subset of 20% was reviewed independently by WQ. Full texts were reviewed by both YZ and WQ independently to determine inclusion. We resolved disagreements on inclusion at the title and abstract stage or at the full-text stage through discussion between the two reviewers. The PRISMA flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram

Data charting and collation

YZ first charted data from included articles and entered them into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. We extracted data on the year of publication, country of focus, clinical setting (inpatient, outpatient, ambulatory, emergency or mixed settings), healthcare professional type (PA, NP, others or mixed cadres of staff), study design and participant characteristics. Included articles were then coded by YZ using NVivo (version 1.5.1) focusing on factors influencing the development, recruitment, integration, retention and career development of APPs. We used a thematic and result-based convergent mixed-methods approach [25] to understand and triangulate factors at different health system levels (see Table 1). The coding process is largely interpretive, using both first-order (participants’ own words) and second-order constructs (researchers’ interpretation) [26] to develop understanding, especially as many articles did not specifically focus on integration but had relevant data.

Summarising and reporting findings

We categorised factors into three stages of workforce management (development and recruitment, integration, and retention and career development) and three health system levels (macro, meso and micro). Core thematic areas and subthemes were refined and summarised iteratively within each category. New themes that emerged from the coding analysis but did not fit in any prior themes were listed separately. Preliminary findings were presented to the other authors who were not directly involved in coding to triangulate and increase the trustworthiness of the findings. The PAGER (Patterns, Advances, Gaps, Evidence for practice and Research recommendations) framework was also used to summarise major gaps and recommendations [27].

The review team members are primarily health systems researchers and clinicians working on a project focusing on PAs in NHS hospitals. While none of the members is professionally aligned with any type of APPs, the review findings were also presented to a broad network of PA stakeholders in the UK including PAs, clinicians working with PAs, educators, hospital managers and regulators, to further sense-check the relevance of these findings. The combination of outsider-insider views further validates our understanding of the topic.

Results

Article overview

Of 4286 citations identified after deduplication, 273 met inclusion criteria after the full-text review. The characteristics of the included articles are provided in Table 2 and Additional file 2. The majority of articles focused on high-income countries and territories, especially US (n = 115) and UK (n = 52), whereas only 7 focused on low- and middle-income countries, including Malawi, Zambia, Uganda and Kenya. Sixty-seven percent (n = 183) of articles focused on NPs, 15% (n = 41) focused on PAs and the rest focused on a mix of different cadres or other cadres like anaesthesia associates. One hundred and two articles discussed the development and recruitment of APPs, 221 discussed integration and only 43 articles analysed the retention and career development of APPs. Major thematic areas that summarised different factors are presented in Table 3 and explained below. The full list of subthemes with supporting data is provided in Additional file 3. Main findings, associated research gaps and future research recommendations are provided in Additional file 4.

Table 2.

Summary of included articles characteristics

| Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Country or territory | |

| US | 115 (42%) |

| UK | 52 (19%) |

| Canada | 25 (9%) |

| Australia | 21 (8%) |

| Netherlands | 11 (4%) |

| Ireland | 7 (3%) |

| Taiwan | 6 (2%) |

| Others | 36 (13%) |

| Year of publication | |

| 2020–2023 | 61 (22%) |

| 2010–2019 | 152 (56%) |

| 2000–2009 | 60 (22%) |

| Study design | |

| Quantitative | 128 (47%) |

| Qualitative | 117 (43%) |

| Mixed methods | 28 (10%) |

| Professional role/cadre of focus | |

| Nurse practitioner | 183 (67%) |

| Physician assistant/associate | 41 (15%) |

| Clinical officer | 7 (3%) |

| Mixed cadre | 38 (14%) |

| Others | 4 (1%) |

| Setting | |

| Inpatient | 91 (33%) |

| Outpatient | 18 (7%) |

| Emergency | 51 (19%) |

| Ambulatory | 1 (0.3%) |

| Other mixed setting | 112 (41%) |

| Focus | |

| Development and recruitment | 102 (37%) |

| Integration | 221 (81%) |

| Retention and career development | 43 (16%) |

Table 3.

Summary table of factors influencing the development, recruitment, integration, retention and career development of advanced practice providers (APPs)

| Level | Development and recruitment | Integration | Retention and career development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macro (system-wide) |

• APP and other workforce supply • National or regional workforce policy • Views of external stakeholders and collaborators |

• National or regional scope of work and service reimbursement policy • APP representation outside of organisations |

• Career recognition, structure and pathways |

| Meso (organisational and departmental) |

• Characteristics of hospitals and departments • Organisational need and planning • Organisational policy and arrangement • Resources and processes for role development and recruitment • Local experience and evidence • Organisational leaders’ or champions’ perception and understanding • Views of other departments and teams |

• Organisational culture • Organisational strategy and planning • Organisational policy and arrangement • Resources to support role activities and integration • Clinical training resource and opportunities • Local experience and evidence • Organisational leaders’ or champions’ perception and understanding • Views of other departments and teams • APP representation in organisations |

• Organisational culture • Organisational strategy and planning • Organisational policy and arrangement • Resources and opportunities for continued employment and career development • Organisational leaders’ attitude |

| Micro (individual and interpersonal) |

• APP individual interest and intention • Clinical team members’ perception and understanding • Patient perception or preference |

• APP individual background and attribute • APP individual skills and expertise • Relationships and negotiations with clinical team members and peers • Autonomy and relationships with supervisors • Patient perception or preference of APP |

• APP individual background • APP work experience and beliefs • Relationship with clinical team members and peers |

Macro-level system-wide factors

We found that the broader workforce supply influenced organisations’ decisions on whether or not to develop and recruit APPs. Whereas many countries have an increasing supply of APPs, in some cases there was a relative shortage of APPs with specific specialty training and this impeded organisations’ development and recruitment decisions [28–30]. There were also examples of an increasing supply of medical students and residents with hospitals concerned that recruiting APPs would lead to competition for training opportunities [31, 32].

National or regional workforce policies played important roles in APP development and recruitment decisions and also impacted whether or not APPs could be fully integrated into clinical teams. While the national or regional government might issue broad policy guidance or have specific funding streams encouraging APP role development [30, 33–36], their relatively limited scope of practice and regulations for prescription [37–39], billing and service reimbursement [39, 40] led to organisations’ hesitancy to develop and recruit APPs, or when they were recruited their integration was more challenging [32, 41–43]. Workforce policies such as work-hour restrictions on medical trainees encouraged organisations to consider developing and recruiting APP roles [44–47]. Lastly, whether national workforce policies and regulators recognise APP role titles especially those with further specialised training [48, 49] and whether there is a clear and well-developed career progression pathway in the system [30, 50, 51] impacted APPs’ retention and career development.

Similarly important for recruitment, development and integration are views of external collaborators, stakeholders, as well as public representation of APPs. This included, for example, support or opposition from professional associations of physicians [37], or from other hospital collaborators such as specific charities [52, 53]. How APPs are being represented outside of organisations such as public images and advocacy for APPs also influenced whether they could be successfully integrated into clinical teams [54, 55].

Meso-level organisational and departmental factors

Specific hospital characteristics influenced decisions to develop and recruit APPs, for example academic hospitals affiliated with APP training institutions and rural facilities that have challenges in staffing were reported to be more likely to consider developing and recruiting APPs [39, 56].

Many articles highlighted the importance of organisational planning and strategy in APP role development, recruitment, integration, retention and career development. The organisational view of existing workforce shortages [37, 57], service gaps [58, 59] and anticipated roles and values [30, 44, 60–62] of APPs often influenced whether APPs were recruited and their specific category. For example, this included organisations aiming for service expansion requiring less specialised APPs to meet the increasing demand for lower acuity patients [60], those intending that APPs take on more quality improvement roles [30, 63] when hospital ratings were assessed as low by regulators. While APPs were often prioritised for filling rotas, improving patient continuity and holistic care [30, 40, 42, 64, 65], sometimes there could be disagreement between hospital leadership over role priorities that impeded role enactment and integration [66], or APPs might be prioritised for clinical functions only without supporting them as individuals which could lead to dissatisfaction and poor retention [67, 68]. Often, organisational planning and strategy are linked with organisational leaders’ or champions’ perception and understanding of APP roles. Poor understanding of what APPs are, concerns over autonomy and working hour arrangements sometimes impeded role development, integration and retention [37, 44, 68–71], whereas key champions and advocates from the organisation and departments played a huge role in facilitating role development, recruitment and integration [66, 72–75]. Local experiences and evidence of APPs were relevant to the development and integration of APP roles in many cases. Previous positive or negative experiences of APPs often encourage or discourage organisations or departments to consider APPs [30, 76–78]. Organisations sometimes conducted local assessments and reviews to guide planning on APP roles and continuous audits, monitoring and evaluation to continue refining the role [30, 52, 54, 77, 79–81]. Organisational culture such as organisational stability, power dynamics and willingness to embrace changes also influenced APP integration [30, 82, 83] and retention [70, 84]. For example, the distribution of power between medical and nursing leaders and which directorate APPs are situated within often influence their practice scope and activities [83]. In organisations that are more stable and with low staff turnover, APPs are also less likely to leave [70].

Organisational policy and arrangement also influenced all stages of APP role management. These included developing and updating governance, policies and protocols such as job descriptions [50, 75, 85, 86], employee management such as recruitment and onboarding processes [31, 86–89], line management structure, workspace, rota and pay arrangements [85, 90–93], opportunities for APP to engage in different specialty clinics and other opportunities [42, 94, 95] but also to ensure clinical training resources and opportunities are not taken away from medical doctors [89, 96, 97]. These often require a significant amount of resources and time investment to fully develop [98–100] and support [42, 49, 93–95, 101] APP roles and communicate transparently with the existing staff. Examples from Queensland Health in Australia indicated that the organisation spent a significant amount of time and resources consulting with medical and nursing colleges, planning workshops and presenting to all staff, producing detailed documentation and involving doctors in the interview and recruitment processes [31]. Such efforts ensured that PAs were accepted by doctors and nurses, and their benefits to the clinical team outweighed the potential concerns such as taking away opportunities for doctors and nurses themselves [31]. Articles from low- and middle-income countries often highlighted the lack of resources significantly impeded APPs’ role enactment and career progress [50, 101]. Also relevant to these areas is performance appraisals, as many organisations included this to encourage personal and professional development but often the value and impact of APP roles proved to be hard to measure and quantify [30, 50, 67, 102].

At the meso-level, the views of other departments and teams, as well as APP representation within organisations, are important. This was especially true when APP roles were proposed or developed in one specific department and physicians from other specialties actively demonstrate resistance to work with APPs, which impeded role development [37, 71] and integration [93, 103, 104]. In comparison, having APP representation across different hospital teams and practice areas as well as in organisational planning facilitated their integration [105, 106].

Micro-level individual and interpersonal factors

Individual APPs’ backgrounds, interests, experiences and expertise directly influenced how they are recruited, integrated and retained. Personal interest in specific roles, specialties, work-life and family considerations often influence the supply of APPs to recruit [77, 107] and whether they would stay in the organisations [43, 94]. We also found that APPs’ prior clinical experience and practical clinical and inter-personal expertise [42, 90, 108–110] (for example NPs prior work as nurses) improved APPs’ credibility in the eyes of other healthcare team members [89, 111, 112]. Such prior work can also, however, lead to an individual’s role confusion or even conflict as they transition from previous roles into APP roles [86, 113, 114] which impedes successful integration.

Clinical team members’ perception, understanding and relationship with APP roles are commonly reported in the included articles as key factors across all stages of role management. This included recognition of APP competence or concern over them being ‘cheap alternatives’ that influenced the organisational decision to develop APP roles [44, 73] and processes for integration [30, 42, 75, 86, 115]. Positive or negative encounters with team members, mentors/supervisors and peers also affected integration [32, 75, 90, 116], retention and long-term career development [30, 68, 70, 117–119]. We found that relationships with clinical team members often included APPs understanding and navigating workplace professional hierarchy and power [50, 106, 117, 119, 120], and trying to negotiate roles and boundaries over time [121–124]. Another interesting factor is the autonomy of APP roles, as APPs often reported insufficient autonomy or others misinterpreting autonomy as meaning ‘doing everything on their own’ which negatively impacted teamwork and integration [106, 115].

Lastly, we found that patient perceptions and preferences often influenced organisations’ decisions to develop, recruit and integrate APPs. Interestingly, many articles reported more negative impressions of or perceived patient preferences from organisational leaders and clinical team members when developing APP roles [28, 59, 98]. In comparison, patients’ own perspectives ranged from having strong preferences for doctors, having no idea who APPs are, to being less concerned over service providers so long as they are seen [86, 122, 125, 126]. Their preferences were often related to the specific services and severity of conditions but actual encounters were commonly described more positively by patients [30, 54].

Other emerging themes

We have also identified three emerging cross-cutting themes. First, while we focused on APP roles in general and there are similarities between different APP roles in secondary care which is doctor-centric, there were key differences between different APPs, especially PAs and NPs. How other clinical team members perceived APPs was related to the APPs’ background [73, 75, 77]. NPs usually have years of working experience as nurses before being retrained and therefore are more familiar with the healthcare settings. Other clinical team members also perceived them to be more credible which facilitated their integration [44, 77, 86, 127], whereas PAs in many countries require no prior clinical work experience and were recruited into clinical teams fresh out of training [59, 73].

Second, included articles highlighted the flexibility and fluidity of APP roles, which is both a blessing and a curse for organisations. Diverse APP roles exist within hospital settings [31, 93]; for example there were four types of clinical nurse consultants within one Australian hospital with differences in specialty, expertise and role focus [86]. Such flexibility and fluidity could ensure APP roles respond to specific local service needs, and especially for NPs the fluidity of role boundaries bridging medical and nursing roles may further improve continuity of patient care. However, this created role ambiguity and self-doubt amongst APPs [75, 106, 128, 129], confusion and conflicts with doctors and other clinical team members around APP roles and responsibilities [30, 122], and made standardisation of protocols, policies and performance appraisals challenging [30, 67, 75, 85].

Lastly, many articles emphasised that it takes significant time and resources to develop and integrate APPs roles. This included time and resources for organisation management to develop strategies and guidelines, communicate and gather input from staff, and even find a suitable APP to recruit [31, 52, 100]; for individual APPs to familiarise themselves with the clinical systems and form new identities [90, 112]; and also for other clinical team members to socialise and build trust with APPs over time [41, 42, 130].

Discussion

Our scoping review of 273 articles summarised different factors influencing the development, recruitment, integration, retention and career development of APP roles in secondary care teams across the global literature. These spanned health system structural levels, from national and regional workforce policies and regulations, organisational and department planning, strategy and resources, to individual APP attributes and interpersonal relationships between team members.

APP roles have been developed largely to meet changing healthcare demands as well as hospitals’ increasing staff shortages [1, 5, 131]. Increasing APP supply from training programmes, work-hour restrictions on doctors and over-reliance on locum staff have prompted hospitals to consider developing and recruiting new roles to provide the much-needed continuity and stability for patients and the team [132, 133]. While the introduction of new roles has stretched traditional professional boundaries to ensure patients benefit from health care teams with better skill mixes, it has caused competition between professions, especially with junior doctors who themselves are concerned over their training opportunities, job security and gradually developing their professional identities [134–136]. Such dynamics often influence whether APP roles can be developed and successfully integrated into secondary care teams.

While more articles offered insights into the development, recruitment and integration of APP roles, only 16% investigated APP retention and career development. This could be linked to the fact that many APP roles are defined and developed catering to local needs; thus, mobility of APP in these roles is rather limited across organisations [20]. Thinking about career development is especially important for entry-level APP roles such as PA, and our review specifically highlighted the importance of organisational resources and opportunities for APPs to continuously engage in a variety of specialised clinical, training, research and quality improvement activities.

Our review has important implications for hospital managers. First and foremost, there is no one-size-fits-all scenario for APP role development, integration and retention, and organisations need to develop context-specific solutions and strategies. To ensure success, hospitals need to conduct workforce diagnoses and planning [1, 137, 138] to identify current opportunities and challenges and readiness for new roles and innovations. This can provide the foundation for establishing the value of new roles and possible career pathways envisioned for APP [139, 140]. Organisations also need to decide if, where and what APP role would be most helpful (for example PA, NP or other roles) and whether APP would take on a more generalist or specialist role [20]. Second, organisations need to recognise developing and integrating APP roles requires significant time and resource investment, often multi-year journeys. Using APP as a short-term fix without careful local planning and design can cost rather than save, fragment care, threaten quality and further worsen organisational stability, especially when services and resources are already stretched [1]. However, if carefully planned, APP could bring long-term positive changes to the clinical team including job satisfaction and interprofessional collaborations as well as improved patient outcomes [30, 110, 141]. Importantly, organisations also need clear and transparent communications of their strategies and processes. Introducing new roles could be perceived as a threat to pre-existing professional identities and jurisdictions, and further proliferation of different APP roles and titles managed by different models could further cause confusion and uncertainty for the workforce as well as for patients [131, 136]. Organisations need early and continuous engagement of local staff across departments and teams, patient representatives and external collaborators to develop and sustain APP roles.

Our findings also highlighted the importance of national policies and regulations in guiding APP role development. In countries and settings where regulation of APP roles is lacking, further clarity and guidance on professional regulation, scope of practice and career development framework is needed from national regulators in consultations with existing APP workforce, professional associations and unions, as well as patient advocacy groups [142, 143].

While this study provides a comprehensive review of APP development, recruitment, integration, retention and career development in secondary care drawing from literature across high-income and low- and middle-income countries, several limitations should be considered while interpreting these findings. Firstly, this was a scoping review and we did not, therefore, systematically assess the quality of the included articles. We also did not systematically rate our confidence in each thematic finding, but have provided the number of supporting articles for each theme and subtheme in Additional file 3. Secondly, we used an interpretative approach to data charting and collation; for example several articles had a different primary focus than workforce integration. As the review team members are primarily health systems researchers and clinicians and do not include PAs or NPs, a different research team might provide a different interpretation of the data. Lastly, we acknowledge our characterisation of APPs as a single unit could be overly simplistic. We grouped APPs because of their often overlapping scope of practice in hospital settings and it has been used by Medicare and Medicaid for coding and billing purposes, but we recognised differences between PA and NP in our analysis. In our analysis, all factors but one applied to both PA and NP roles. The exception ‘individual interest or lack of interest in advancing to APP roles’ is unique to nurses advancing to NP roles, and this factor influenced APP development and recruitment. We also acknowledge that there could be further differences within various types of advanced nursing roles such as nurse practitioners and nurse specialists [144], and we recommend future studies focus on one specific role, e.g. PA or NP, and whereas possible continue to compare and clarify the differences in these roles.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we summarised a wide range of factors influencing the development, recruitment, integration, retention and career development of APP roles in secondary care teams. We highlighted the importance of national and regional workforce policies, organisational and departmental planning, processes and resources, as well as individual APP characteristics and interpersonal relationships with clinical team members. Organisations need to recognise that there is no one-size-fits-all scenario for developing and integrating APPs. Long-term investment with significant resource input and transparent processes is needed to develop context-specific workforce solutions and strategies to tackle evolving healthcare challenges.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Example search strategy in Ovid Embase.

Additional file 2: Characteristics of included studies.

Additional file 3: Themes, subthemes and example quotes.

Additional file 4: Summary of factors and emerging themes based on PAGER framework.

Acknowledgements

We thank Eli Harriss, the Knowledge Centre Manager at the Bodleian Health Care Libraries, University of Oxford for her support in literature search, and Rhys Swainston from Nuffield Department of Medicine Centre for Global Health Research, University of Oxford for reading an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- APP

Advanced practice provider

- NP

Nurse practitioner

- PA

Physician assistant/associate

- PAGER

Patterns, Advances, Gaps, Evidence for practice and Research recommendations

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

Authors’ contributions

YZ, SN, GW, ME and AL conceived of the analysis. YZ and WQ conducted study selection. YZ conducted data charting and collation, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. WQ, SN, GW, ME and AL provided critical feedback on the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study is funded by the NIHR Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR) (NIHR153324). ME is supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship (#207522). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Availability of data and materials

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as additional files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not required.

Consent for publication

Not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yingxi Zhao and Wesley Quadros contributed equally to this manuscript as joint first authors.

References

- 1.Reshaping the workforce to deliver the care patients need. Nuffield Trust. 2016. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/reshaping-the-workforce-to-deliver-the-care-patients-need. Accessed 28 Feb 2024.

- 2.Avgar AC, Vogus TJ. The Evolving Health Care Landscape: How Employees, Organizations, and Institutions are Adapting and Innovating. Labor and Employment Relations Association; 2016. ISBN 0913447129, 9780913447123.

- 3.Advanced practice nonphysician practitioners | CMS. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/physician-fee-schedule/advanced-practice-nonphysician-practitioners. Accessed 8 May 2024.

- 4.Mullan F, Frehywot S. Non-physician clinicians in 47 sub-Saharan African countries. Lancet. 2007;370:2158–2163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60785-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leary A, MacLaine K. The evolution of advanced nursing practice: past, present and future. Nursing Times. 2019. https://www.nursingtimes.net/roles/specialist-nurses/evolution-advanced-nursing-practice-past-present-future-10-09-2019/. Accessed 28 Feb 2024.

- 6.Cawley JF. Physician assistant education: an abbreviated history. J Physician Assist Educ. 2007;18:6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smalley S, Bruza-Augatis M, Colletti T, Heistermann P, Mahmud A, Song D, et al. Curricula mapping of physician associate/physician assistant-comparable professions worldwide using the learning opportunities, objectives, and outcomes platform. J Physician Assist Educ. 2024;35:108. doi: 10.1097/JPA.0000000000000571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wheeler KJ, Miller M, Pulcini J, Gray D, Ladd E, Rayens MK. Advanced practice nursing roles, regulation, education, and practice: a global study. Ann Glob Health. 2022;88:42. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pulcini J, Jelic M, Gul R, Loke AY. An international survey on advanced practice nursing education, practice, and regulation. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2010;42:31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts K, Drennan VM, Watkins J. Physician associate graduates in England: a cross-sectional survey of work careers. Future Healthc J. 2022;9:5–10. doi: 10.7861/fhj.2021-0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarzynski E, Barry H. Current evidence and controversies: advanced practice providers in healthcare. Am J Manag Care. 2019;25:366–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Advanced practice | NHS Employers. https://www.nhsemployers.org/articles/advanced-practice. Accessed 1 May 2024.

- 13.Halter M, Wheeler C, Pelone F, Gage H, de Lusignan S, Parle J, et al. Contribution of physician assistants/associates to secondary care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019573. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsiachristas A, Wallenburg I, Bond CM, Elliot RF, Busse R, van Exel J, et al. Costs and effects of new professional roles: evidence from a literature review. Health Policy. 2015;119:1176–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jennings N, Clifford S, Fox AR, O’Connell J, Gardner G. The impact of nurse practitioner services on cost, quality of care, satisfaction and waiting times in the emergency department: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:421–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carranza AN, Munoz PJ, Nash AJ. Comparing quality of care in medical specialties between nurse practitioners and physicians. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2021;33:184. doi: 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Htay M, Whitehead D. The effectiveness of the role of advanced nurse practitioners compared to physician-led or usual care: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud Adv. 2021;3:100034. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnsa.2021.100034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woo BFY, Lee JXY, Tam WWS. The impact of the advanced practice nursing role on quality of care, clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and cost in the emergency and critical care settings: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15:63. doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0237-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleinpell RM, Grabenkort WR, Kapu AN, Constantine R, Sicoutris C. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in acute and critical care: a concise review of the literature and data 2008–2018. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:1442–1449. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Bont A, van Exel J, Coretti S, Ökem ZG, Janssen M, Hope KL, et al. Reconfiguring health workforce: a case-based comparative study explaining the increasingly diverse professional roles in Europe. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1898-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H, English M, Chakma S, Namedre M, Hill E, Nagraj S. The roles of physician associates and advanced nurse practitioners in the National Health Service in the UK: a scoping review and narrative synthesis. Hum Resour Health. 2022;20:69. doi: 10.1186/s12960-022-00766-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skills for care. The principles of workforce integration. 2021. https://www.skillsforcare.org.uk/resources/documents/Support-for-leaders-and-managers/Integration/The-principles-of-workforce-integration.pdf. Accessed 19 Feb 2024

- 24.Wallace BC, Small K, Brodley CE, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Deploying an interactive machine learning system in an evidence-based practice center: abstrackr. In: Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGHIT international health informatics symposium. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2012. pp. 819–24. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, Wassef M. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev. 2017;6:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0454-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnett-Page E, Thomas J. Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradbury-Jones C, Aveyard H, Herber OR, Isham L, Taylor J, O’Malley L. Scoping reviews: the PAGER framework for improving the quality of reporting. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2022;25:457–470. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2021.1899596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colvin L, Cartwright A, Collop N, Freedman N, McLeod D, Weaver TE, et al. Advanced practice registered nurses and physician assistants in sleep centers and clinics: a survey of current roles and educational background. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10:581–587. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan L, Klein T. Nurse practitioner hospitalists: an empowered role. Nurs Outlook. 2021;69:856–864. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2021.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drennan VM, Halter M, Wheeler C, Nice L, Brearley S, Ennis J, et al. The role of physician associates in secondary care: the PA-SCER mixed-methods study. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurti L, Rudland S, Wilkinson R, Dewitt D, Zhang C. Physician’s assistants: a workforce solution for Australia? Aust J Prim Health. 2011;17:23–28. doi: 10.1071/PY10055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Offenbeek M, Sorge A, Knip M. Enacting fit in work organization and occupational structure design: the case of intermediary occupations in a Dutch hospital. Organ Stud. 2009;30:1083–1114. doi: 10.1177/0170840609337954. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryder M, Gallagher P. A survey of nurse practitioner perceptions of integration into acute care organisations across one region in Ireland. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30:1053–1060. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rudrum I, Mahalingam N, Bura M. Assistant practitioners in palliative care: doing things differently. British Journal of Healthcare Assistants. 2018;12:610–612. doi: 10.12968/bjha.2018.12.12.610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Decloe M, McCready J, Downey J, Powis J. Improving health care efficiency through the integration of a physician assistant into an infectious diseases consult service at a large urban community hospital. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2015;26:130–132. doi: 10.1155/2015/857890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oddsdóttir EJ, Sveinsdóttir H. The content of the work of clinical nurse specialists described by use of daily activity diaries. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1393–1404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Timmermans MJC, van Vught AJAH, Maassen ITHM, Draaijer L, Hoofwijk AGM, Spanier M, et al. Determinants of the sustained employment of physician assistants in hospitals: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011949. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI, Staiger DO. Implications of the rapid growth of the nurse practitioner workforce in the US: an examination of recent changes in demographic, employment, and earnings characteristics of nurse practitioners and the implications of those changes. Health Aff. 2020;39:273–279. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carlsen S. Identifying practice barriers to use of adult gerontology-acute care nurse practitioners in the northern Nevada region. The University of Arizona; 2015. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1719260888.

- 40.Kilpatrick K, Harbman P, Carter N, Martin-Misener R, Bryant-Lukosius D, Donald F, et al. The acute care nurse practitioner role in Canada. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont). 2010;23 Spec No 2010:114–39. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2010.22272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore J, Prentice D. Collaboration among nurse practitioners and registered nurses in outpatient oncology settings in Canada. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:1574–1583. doi: 10.1111/jan.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor F, Drennan VM, Halter M, Calestani M. Integration and retention of American physician assistants/associates working in English hospitals: a qualitative study. Health Policy. 2020;124:525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harkins T, Thomas J, Fontenot B, Day J, Faraone M. Utilization and workforce integration of physician assistants. J Nurs Interprof Leadersh Qual Saf (JoNILQS). 2021;4. https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/uthoustonjqualsafe/vol4/iss1/6.

- 44.Davies J, Bickell F, Tibby SM. Attitudes of paediatric intensive care nurses to development of a nurse practitioner role for critical care transport. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67:317–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gilfedder M, Barron D, Docherty E. Developing the role of advanced nurse practitioners in mental health. Nurs Stand. 2010;24:35–40. doi: 10.7748/ns.24.30.35.s50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White CN, Borchardt RA, Mabry ML, Smith KM, Mulanovich VE, Rolston KV. Multidisciplinary cancer care: development of an infectious diseases physician assistant workforce at a comprehensive cancer center. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6:e31–34. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reilly BK, Brandon G, Shah R, Preciado D, Zalzal G. The role of advanced practice providers in pediatric otolaryngology academic practices. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith SL, Hall MA. Developing a neonatal workforce: role evolution and retention of advanced neonatal nurse practitioners. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F426–429. doi: 10.1136/fn.88.5.F426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gajewski J, Wallace M, Pittalis C, Mwapasa G, Borgstein E, Bijlmakers L, et al. Why do they leave? Challenges to retention of surgical clinical officers in district hospitals in Malawi. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2022;11:354–361. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bradley S, McAuliffe E. Mid-level providers in emergency obstetric and newborn health care: factors affecting their performance and retention within the Malawian health system. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:14. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheng H-L, Tung H-H, Guu S-M, Tsay S-L, Chang C-F. Perceptions of NPs and administrators in regard to the governing and supervision of NPs in Taiwan. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2012;24:132–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2011.00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jokiniemi K, Korhonen K, Kärkkäinen A, Pekkarinen T, Pietilä A-M. Clinical nurse specialist role implementation structures, processes and outcomes: participatory action research. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30:2222–2233. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leary A, Mak V, Trevatt P. The variance in distribution of cancer nurse specialists in England. Br J Nurs. 2011;20:228–230. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.4.228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plath SJ, Bratby JA, Poole L, Forristal CE, Morel DG. Nurse practitioners in the emergency department: establishing a successful service. Collegian. 2019;26:457–462. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2018.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Kraaij J, van Oostveen C, Vermeulen H, Heinen M, Huis A, Adriaansen M, et al. Nurse practitioners’ perceptions of their ability to enact leadership in hospital care. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:447–458. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scherff P, Siclovan D. Organizational strategies to recruit clinical nurse specialists. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39:14–18. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31818e9d45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hayden C, Burlingame P, Thompson H, Sabol VK. Improving patient flow in the emergency department by placing a family nurse practitioner in triage: a quality-improvement project. J Emerg Nurs. 2014;40:346–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farley TL, Latham G. Evolution of critical care nurse practitioner role within a US academic medical center. ICU Dir. 2011;2:16–19. doi: 10.1177/1944451611405318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beresford JV. Role of physician assistants in rural hospital settings in the Virgin Islands: a case study. PhD Thesis. University of Phoenix; 2014. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1668318111/CFA605BAD9924085PQ.

- 60.Menchine MD, Wiechmann W, Rudkin S. Trends in midlevel provider utilization in emergency departments from 1997 to 2006. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:963–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hurlock-Chorostecki C, Forchuk C, Orchard C, Reeves S, van Soeren M. The value of the hospital-based nurse practitioner role: development of a team perspective framework. J Interprof Care. 2013;27:501–508. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.796915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shannon EM, Cauley M, Vitale M, Wines L, Chopra V, Greysen SR, et al. Patterns of utilization and evaluation of advanced practice providers on academic hospital medicine teams: a national survey. J Hosp Med. 2022;17:186–191. doi: 10.1002/jhm.12788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Drennan VM, Halter M, Wheeler C, Nice L, Brearley S, Ennis J, et al. What is the contribution of physician associates in hospital care in England? A mixed methods, multiple case study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027012. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fawdon H, Adams J. Advanced clinical practitioner role in the emergency department. Nurs Stand. 2013;28:48–51. doi: 10.7748/ns2013.12.28.16.48.e8294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gajewski J, Mweemba C, Cheelo M, McCauley T, Kachimba J, Borgstein E, et al. Non-physician clinicians in rural Africa: lessons from the Medical Licentiate programme in Zambia. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15:53. doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0233-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kilpatrick K, Lavoie-Tremblay M, Ritchie JA, Lamothe L, Doran D, Rochefort C. How are acute care nurse practitioners enacting their roles in healthcare teams? A descriptive multiple-case study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:850–862. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gibson F, Bamford O. Focus group interviews to examine the role and development of the clinical nurse specialist. J Nurs Manag. 2001;9:331–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lögde A, Rudolfsson G, Broberg RR, Rask-Andersen A, Wålinder R, Arakelian E. I am quitting my job. Specialist nurses in perioperative context and their experiences of the process and reasons to quit their job. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30:313–20. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzy023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.D’Agostino R, Halpern NA. Acute care nurse practitioners in oncologic critical care: the memorial Sloan-Kettering cancer center experience. Crit Care Clin. 2010;26:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arakelian E, Rudolfsson G, Rask-Andersen A, Runeson-Broberg R, Wålinder R. I stay-Swedish specialist nurses in the perioperative context and their reasons to stay at their workplace. J Perianesth Nurs. 2019;34:633–644. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2018.06.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Norris T, Melby V. The acute care nurse practitioner: challenging existing boundaries of emergency nurses in the United Kingdom. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:253–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Johnson JH. Cardiology nurse practitioners: who are we? The development of the role at the Mount Sinai Hospital. Cardiac Cath Lab Director. 2011;1:72–78. doi: 10.1177/2150133511407762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.White H, Round JEC. Introducing physician assistants into an intensive care unit: process, problems, impact and recommendations. Clin Med (Lond) 2013;13:15–18. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.13-1-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cartwright CC. Job satisfaction and retention of an advanced practice registered nurse fellowship program. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2021;37:E15–E19. doi: 10.1097/NND.0000000000000720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Van Hecke A, Vlerick I, Akhayad S, Daem M, Decoene E, Kinnaer L-M. Dynamics and processes influencing role integration of advanced practice nurses and nurse navigators in oncology teams. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2023;62:102257. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2022.102257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Halter M, Wheeler C, Drennan VM, de Lusignan S, Grant R, Gabe J, et al. Physician associates in England’s hospitals: a survey of medical directors exploring current usage and factors affecting recruitment. Clin Med (Lond) 2017;17:126–131. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-2-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thrasher C, Purc-Stephenson RJ. Integrating nurse practitioners into Canadian emergency departments: a qualitative study of barriers and recommendations. CJEM. 2007;9:275–281. doi: 10.1017/S1481803500015165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schirle L, McCabe BE, Mitrani V. The relationship between practice environment and psychological ownership in advanced practice nurses. West J Nurs Res. 2019;41:6–24. doi: 10.1177/0193945918754496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Collett S, Vaghela D, Bakhai A. Cardiovascular innovations: role, impact and first-year experience of a physician assistant. Br J Cardiol. 2012;19(4):178. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wand T, White K, Patching J. Realistic evaluation of an emergency department-based mental health nurse practitioner outpatient service in Australia. Nurs Health Sci. 2011;13:199–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hyde R. An advanced nurse practitioner service for neonates, children and young people. Nurs Child Young People. 2017;29:36–41. doi: 10.7748/ncyp.2017.e938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barton D, Mashlan W. An advanced nurse practitioner-led service - consequences of service redesign for managers and organizational infrastructure. J Nurs Manag. 2011;19:943–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kilpatrick K. Understanding acute care nurse practitioner communication and decision-making in healthcare teams. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:168–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Becker DM. Implementing a night-shift clinical nurse specialist. Clin Nurse Spec. 2013;27:26–30. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e3182777029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roberts S, Howarth S, Millott H, Stroud L. WORKFORCE: “What can you do then?” Integrating new roles into healthcare teams: regional experience with physician associates. Future Healthc J. 2019;6:61–66. doi: 10.7861/futurehosp.6-1-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Duke CR. The lived experience of nurse practitioner graduates’ transition to hospital-based practice. East Carolina University; 2010. https://www.proquest.com/docview/753511328/606E01024345484CPQ.

- 87.Simone S, McComiskey CA, Andersen B. Integrating nurse practitioners into intensive care units. Crit Care Nurse. 2016;36:59–69. doi: 10.4037/ccn2016360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kapu AN, Thomson-Smith C, Jones P. NPs in the ICU: the Vanderbilt initiative. Nurse Pract. 2012;37:46–52. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000413485.97744.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cusson RM, Strange SN. Neonatal nurse practitioner role transition: the process of reattaining expert status. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2008;22:329–337. doi: 10.1097/01.JPN.0000341365.60693.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schoales CA, Bourbonnais FF, Rashotte J. Building to make a difference: advanced practice nurses’ experience of power. Res Theory Nurs Pract. 2018;32:96–116. doi: 10.1891/0000-000Y.32.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chien WT, Ip WY. Perceptions of role functions of psychiatric nurse specialists. West J Nurs Res. 2001;23:536–554. doi: 10.1177/01939450122045267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Monette DL, Baccari B, Paskind L, Reisman D, Temin ES. The design and implementation of a professional development program for physician assistants in an academic emergency department. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4:154–157. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Burrows KE, Abelson J, Miller PA, Levine M, Vanstone M. Understanding health professional role integration in complex adaptive systems: a multiple-case study of physician assistants in Ontario. Canada BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:365. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05087-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rakhab A, Jackson C, Nilmanat K, Butterworth T, Kane R. Factors supporting career pathway development amongst advanced practice nurses in Thailand: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;117:103882. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fung Y-L, Chan ZCY, Chien W-T. We are different: the voices of psychiatric advanced practice nurses on the performance of their roles. Contemp Nurse. 2016;52:13–29. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2016.1194724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Polansky MN, Govaerts MJB, Stalmeijer RE, Eid A, Bodurka DC, Dolmans DHJM. Exploring the effect of PAs on physician trainee learning: an interview study. JAAPA. 2019;32:47–53. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000554742.08935.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sellers C, Penfold N, Gass C, Drennan VM. The experience of working with anaesthesia associates in the United Kingdom and the impact on medical anaesthetic training. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2022;37:2767–2778. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Melby V, Gillespie M, Martin S. Emergency nurse practitioners: the views of patients and hospital staff at a major acute trust in the UK. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:236–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Innes K, Jackson D, Plummer V, Elliott D. Exploration and model development for emergency department waiting room nurse role: synthesis of a three-phase sequential mixed methods study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2021;59:101075. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2021.101075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Steiner IP, Blitz S, Nichols DN, Harley DD, Sharma L, Stagg AP. Introducing a nurse practitioner into an urban Canadian emergency department. CJEM. 2008;10:355–363. doi: 10.1017/S1481803500010368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chandler CIR, Chonya S, Mtei F, Reyburn H, Whitty CJM. Motivation, money and respect: a mixed-method study of Tanzanian non-physician clinicians. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:2078–2088. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li J, Westbrook J, Callen J, Georgiou A, Braithwaite J. The impact of nurse practitioners on care delivery in the emergency department: a multiple perspectives qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:356. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kitajima M, Miyata C, Tamura K, Kinoshita A, Arai H. Factors associated with the job satisfaction of certified nurses and nurse specialists in cancer care in Japan: analysis based on the Basic Plan to Promote Cancer Control Programs. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0232336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.King R, Sanders T, Tod A. Shortcuts in knowledge mobilization: an ethnographic study of advanced nurse practitioner discharge decision-making in the emergency department. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77:3156–3167. doi: 10.1111/jan.14834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fischer-Cartlidge E, Houlihan N, Browne K. Building a renowned clinical nurse specialist team: recruitment, role development, and value identification. Clin Nurse Spec. 2019;33:266–272. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hurlock-Chorostecki C, Forchuk C, Orchard C, van Soeren M, Reeves S. Labour saver or building a cohesive interprofessional team? The role of the nurse practitioner within hospitals. J Interprof Care. 2014;28:260–266. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.867838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rasmussen LB, Vargo LE, Reavey DA, Hunter KS. Pilot survey of NICU nurses’ interest in the neonatal nurse practitioner role. Adv Neonatal Care. 2005;5:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.adnc.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Boman E, Levy-Malmberg R, Fagerström L. Differences and similarities in scope of practice between registered nurses and nurse specialists in emergency care: an interview study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2020;34:492–500. doi: 10.1111/scs.12753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.van Soeren MH, Micevski V. Success indicators and barriers to acute nurse practitioner role implementation in four Ontario hospitals. AACN Clin Issues. 2001;12:424–437. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200108000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Locatelli G, Ausili D, Stubbings V, Di Mauro S, Luciani M. The epilepsy specialist nurse: a mixed-methods case study on the role and activities. Seizure. 2021;85:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Maoz-Breuer R, Berkowitz O, Nissanholtz-Gannot R. Integration of the first physician assistants into Israeli emergency departments - the physician assistants’ perspective. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2019;8:4. doi: 10.1186/s13584-018-0275-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kennedy C, Brooks Young P, Nicol J, Campbell K, Gray BC. Fluid role boundaries: exploring the contribution of the advanced nurse practitioner to multi-professional palliative care. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:3296–3305. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Maten-Speksnijder AT, Pool A, Grypdonck M, Meurs P, van Staa A. Driven by ambitions: the nurse practitioner’s role transition in Dutch hospital care. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015;47:544–554. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rashotte J, Jensen L. The transformational journey of nurse practitioners in acute-care settings. Can J Nurs Res. 2010;42:70–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lloyd-Rees J. How emergency nurse practitioners view their role within the emergency department: a qualitative study. Int Emerg Nurs. 2016;24:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bahouth MN, Esposito-Herr MB. Orientation program for hospital-based nurse practitioners. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2009;20:82–90. doi: 10.1097/NCI.0b013e3181945422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Weiland TJ, Mackinlay C, Jelinek GA. Perceptions of nurse practitioners by emergency department doctors in Australia. Int J Emerg Med. 2010;3:271–278. doi: 10.1007/s12245-010-0214-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mathur M, Rampersad A, Howard K, Goldman GM. Physician assistants as physician extenders in the pediatric intensive care unit setting-a 5-year experience. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:14–19. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000149133.50687.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.McGinnis JP. Resilience, dysfunctional behavior, and sensemaking: the experiences of emergency medicine physician assistants encountering workplace incivility. PhD Thesis. The George Washington University; 2021. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2476548161/1940C9D40B7542FCPQ.

- 120.Courtenay M, Carey N. Nurse prescribing by children’s nurses: views of doctors and clinical leads in one specialist children’s hospital. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18:2668–2675. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kilpatrick K, Lavoie-Tremblay M, Ritchie JA, Lamothe L, Doran D. Boundary work and the introduction of acute care nurse practitioners in healthcare teams. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:1504–1515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wilsher SH, Gibbs A, Reed J, Baker R, Lindqvist S. Patient care, integration and collaboration of physician associates in multiprofessional teams: a mixed methods study. Nurs Open. 2023;10:3962–3972. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Nelson SC, Hooker RS. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners in rural Washington emergency departments. J Physician Assist Educ. 2016;27:56–62. doi: 10.1097/JPA.0000000000000074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Willard C, Luker K. Working with the team: strategies employed by hospital cancer nurse specialists to implement their role. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:716–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Larkin GL, Hooker RS. Patient willingness to be seen by physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and residents in the emergency department: does the presumption of assent have an empirical basis? Am J Bioeth. 2010;10:1–10. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2010.494216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Gill SD, Stella J, McManus L. Consumer preferences regarding physiotherapy practitioners and nurse practitioners in emergency departments - a qualitative investigation. J Interprof Care. 2019;33:209–215. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2018.1538104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Batty J. An evaluation of the role of the advanced nurse practitioner on an elective orthopaedic ward from the perspective of the multidisciplinary team. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2021;41:100821. doi: 10.1016/j.ijotn.2020.100821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Roche M, Duffield C, Wise S, Baldwin R, Fry M, Solman A. Domains of practice and advanced practice nursing in Australia. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15:497–503. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Choo PJ, Tan JYT, Ong LT, Aw AT, Teo LW, Tan MLM, et al. Role transition: a descriptive exploratory study of assistant nurse clinicians in Singapore. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27:125–132. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Reines HD, Robinson L, Duggan M, O'brien BM, Aulenbach K. Integrating midlevel practitioners into a teaching service. Am J Surg. 2006;192:119–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Abraham J, Bailey L, Coad J, Whiteman B, Kneafsey R. Non-medical practitioner roles in the UK: who, where, and what factors influence their development? Br J Nurs. 2019;28:930–939. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2019.28.14.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kim M, Bloom B. Physician associates in emergency departments: the UK experience. Eur J Emerg Med. 2020;27:5. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hooker RS, Hogan K, Leeker E. The globalization of the physician assistant profession. J Physician Assist Educ. 2007;18:76. doi: 10.1097/01367895-200718030-00011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Abbott A. The system of professions: an essay on the division of expert labor. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Theodoraki M, Hany T, Singh H, Khatri M. Multisource feedback for the physician associate role. Bulletin. 2021;103:206–210. doi: 10.1308/rcsbull.2021.77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Academy of Medical Royal Colleges. Developing professional identity in multi-professional teams. 2020. https://www.aomrc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Developing_professional_identity_in_multi-professional_teams_0520.pdf. Accessed 29 Feb 2024

- 137.NHS England » Workforce planning and resource management. https://www.england.nhs.uk/mat-transformation/matrons-handbook/workforce-planning-and-resource-management/. Accessed 29 Feb 2024.

- 138.gdiesing. The imperative for strategic workforce planning and development: challenges and opportunities | AHA News. https://www.aha.org/news/insights-and-analysis/2018-02-28-imperative-strategic-workforce-planning-and-development. Accessed 29 Feb 2024.

- 139.Ritsema TS, Navarro-Reynolds L. Facilitators to the integration of the first UK-educated physician associates into secondary care services in the NHS. Future Healthc J. 2023;10:31–37. doi: 10.7861/fhj.2022-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Edwards J, Coward M, Carey N. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of non-medical independent prescribing in primary care in the UK: a qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e052227. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Christiansen A, Vernon V, Jinks A. Perceptions of the benefits and challenges of the role of advanced practice nurses in nurse-led out-of-hours care in Hong Kong: a questionnaire study. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:1173–1181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Carney M. Regulation of advanced nurse practice: its existence and regulatory dimensions from an international perspective. J Nurs Manag. 2016;24:105–114. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.King R, Tod A, Sanders T. Development and regulation of advanced nurse practitioners in the UK and internationally. Nursing Standard. 2017;32(14):43-50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 144.Cooper MA, McDowell J, Raeside L, ANP–CNS Group The similarities and differences between advanced nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists. Br J Nurs. 2019;28:1308–14. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2019.28.20.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Example search strategy in Ovid Embase.

Additional file 2: Characteristics of included studies.

Additional file 3: Themes, subthemes and example quotes.

Additional file 4: Summary of factors and emerging themes based on PAGER framework.

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as additional files.