To the editor.

In fit patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (ND-AML), immediate treatment is recommended due to the poor prognosis of untreated acute leukemia; however, this paradigm has been challenged by a German study.1 The authors stratified patients into 4 groups for a time from diagnosis to treatment start (TDT), showing no difference in waiting before starting intensive chemotherapy. The actual clinical practice, therefore, considers it acceptable to delay ND-AML patients completing the laboratory work-up recommended by the European Leukemia Net (ELN2022)2 and solve toxicities present at the time of diagnosis. Turnaround times for targeted gene panels performed with next-generation sequence (NGS) techniques are generally from 5 to 14 days,3 so several days can elapse before a definite clinical entity can be assigned, and some mutations have an impact on the choice of the first line therapy.4 On the contrary, AML patients unfit for intensive chemotherapy are candidates for agnostic therapy encompassing hypomethylating drugs (HMAs) ± venetoclax (VEN)5 or glasdegib + low-doses cytarabine;6 thus, laboratory work-up is not mandatory before choosing the frontline treatment, but molecular determinants of outcome are of prognostic significance.7 Because of the scant data published on TDT in the context of HMAs in ND-AML, we evaluated the prognostic value of TDT in 220 patients with AML older than 75 years, already reported in a multicentric retrospective study in a real-life setting of HMAs usage.8 Patients were treated with only HMAs due to comorbidities. The main reason for treatment delay was the presence of an infectious event at baseline.

In this study, data were collected from patients treated with azacitidine (AZA) (164) and decitabine (DEC) (56) between September 2010 and September 2023. We recorded baseline patient-related and disease characteristics, including age, ECOG, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) scores, kidney function (eGFR and CKD-EPI equation), molecular profiling, ELN 2017, cytogenetic risk, dates of regimen initiation, and survival (Table 1). Patients were divided into 4 cohorts: those that started therapy in <15 days (n= 85 patients), 15–30 days (n = 64 patients), 31–45 days (n= 33 patients), 46 days and beyond (n= 38 patients) from their initial diagnosis of AML (Table 2). These 4 cohorts received homogeneous treatment with HMAs. We analyzed survival using the Kaplan-Meier curves, with significance determined by the log-rank test. The event for calculating the overall survival (OS) was the date of death, and for event-free survival (EFS), was the time of progressive disease, relapse, or death. Patients were otherwise censored at the date of the last follow-up.

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics.

| Characteristics | No. of Patients = 220 |

|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 119 (54) |

| Female, n (%) | 101 (46) |

|

| |

| Median age at diagnosis (IQR) | 78.2 (75–86.2) |

|

| |

| Hb g/dL (median, IQR) | 8.8 (7.9–10.0) |

|

| |

| WBC × 10 9 /L (median, IQR) | 3.24 (1.6–9.8) |

|

| |

| Platelet count × 10 9 /L (median, range) | 56 (32–92.5) |

|

| |

| BMI, n (%) | |

|

| |

| <25 | 97 (44.1) |

| ≥25 | 123 (55.9) |

|

| |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |

|

| |

| <2 | 132 (60) |

| ≥2 | 88 (40) |

|

| |

| eGFR, n (%) | |

|

| |

| <60 mL/min | 37 (16.8) |

| ≥60 mL/min | 183 (83.2) |

|

| |

| CCI, n (%) | |

|

| |

| <3 | 44 (20) |

| ≥3 | 176 (80) |

|

| |

| AML type, n (%) | |

|

| |

| De novo-AML | 135 (61.4) |

| s-AML | 85 (38.6) |

|

| |

| ELN risk stratification, data available n (%) | 205 (93.1) |

|

| |

| Favorable | 17 (8.3) |

| Intermediate | 100 (48.8) |

| Poor/adverse | 88 (42.9) |

|

| |

| Infection at diagnosis, n (%) | |

|

| |

| No | 171 (77.7) |

| Yes | 49 (22.3) |

|

| |

| Transfusion requirement, n (%) | |

| No | 83 (37.7) |

| Yes | 137 (62.3) |

|

| |

| Median No of cycles (IQR) 5. (2–12) | |

|

| |

| TDT, n (%) | |

| <15 days | 85 (38.6) |

| 15–30 days | 64 (29.1) |

| 31–45 days | 33 (15.1) |

| >45 days | 38 (17.2) |

Table 2.

Patients’ subgroups characteristics according to TDT.

| Time from diagnosis to treatment start (TDT) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <15 days | 15–30 days | 31–45 days | >45 days | |

| Patients, n | 85 | 64 | 33 | 38 |

| Median age at diagnosis (IQR) | 77.2 (75–82.3) | 78.6 (75–84.4) | 79.1 (76–86.2) | 78.7 (75–84.8) |

| s-AML | 35 | 20 | 14 | 16 |

| Poor/adverse risk (ELN classification), n | 37 | 24 | 12 | 15 |

| Transfusion dependence, n | 56 | 35 | 20 | 26 |

| Infection at diagnosis, n | 7 | 10 | 14 | 18 |

| ECOG PS ≥2, n | 35 | 24 | 13 | 16 |

| CCI≥3, n | 68 | 50 | 26 | 32 |

| eGFR <60 mL/min, n | 15 | 10 | 4 | 7 |

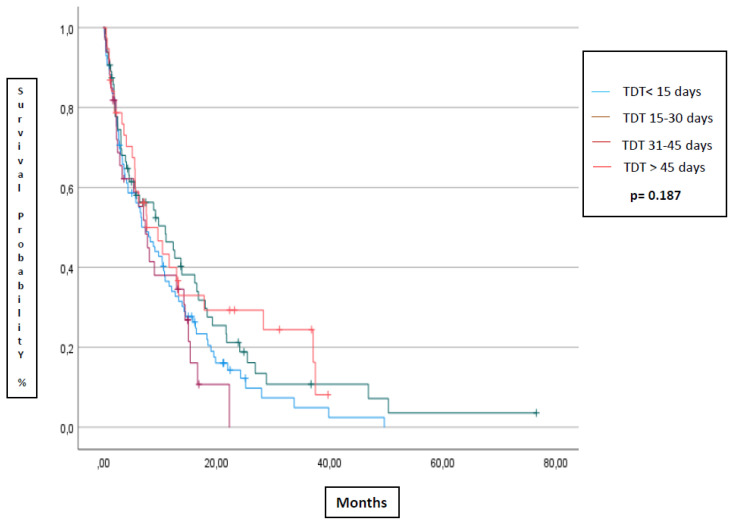

The median TDT of patients treated with AZA or DEC was 21 or 15 days, respectively; overall, it was 19 days. The median OS (Figure 1) was 7.5 months (95%CI 4.5–10.5 mts), 11 months (95%CI 4.5–17.4), 7.4 months (95%CI 4.7–10.1), and 7.6 months (95%CI 2.3–13) for the subgroups of TDT <15, 15–30, 31–45 and >46 days, respectively (p=0.224). The median EFS was 5.8 months (95%CI 2.4–9.1), 9.8 months (95%CI 7.9–11.7), 5.0 months (95%CI 0.9–9.1), and 5.7 months (95%CI 0.5–12.2), for the subgroups of TDT <15, 15–30, 31–45 and >45 days, respectively (p=0.187). No statistically significant difference was noted when considering patients receiving AZA or DEC In terms of OS (p=0.08) and EFS (p=0.083) considering the four different groups.

Figure 1.

Median overall survival according to time from diagnosis to treatment initiation (<15 days, 15–30 days, 31–45 days, >45 days).

In conclusion, TDT did not show prognostic significance in our patients with AML treated with HMAs. However, a trend for better outcomes can be seen in the subgroup that started treatment 15–30 days after initial diagnosis. These results confirm the lack of difference found in the German study1 but, at the same time, do not contrast with the results from Bouligny et al., who considered the impact of TDT on patients treated with VEN + HMAs.9 Indeed, in this study, OS was 5.8 months for patients included in the 0–7 day cohort of VEN+HMA initiation, significantly worse than 8.9 months for the 8–14 day cohort and the 12.7 months for 15 days and beyond (p = 0.023). Our study also found that the earliest TDT and the two delayed groups had worse results than the intermediate 15–30 days TDT group. This result can be explained by the time used to treat disease-related complications and mitigate existent comorbidities that can reduce toxicities related to HMA treatment.

On the other hand, waiting too long to start HMAs worsens the prognosis of AML patients, therefore suggesting a possible temporal window to optimize results. Our study has several limitations, given its retrospective nature and the fact that time-passing bias can be present, considering that HMAs are actually rarely given without venetoclax. Therefore, more studies have to be developed to find the best temporal window in TDT when starting HMA + VEN, which could help to improve the results of patients with AML.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no conflict of Interest.

References

- 1.Röllig C, Kramer M, Schliemann C, Mikesch J-H, Steffen B, Krämer A, Noppeney R, Schäfer-Eckart K, Krause SW, Hänel M, et al. Does Time from Diagnosis to Treatment Affect the Prognosis of Patients with Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia? Blood. 2020;136:823–830. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Döhner H, Wei AH, Appelbaum FR, Craddock C, DiNardo CD, Dombret H, Ebert BL, Fenaux P, Godley LA, Hasserjian RP, et al. Diagnosis and Management of AML in Adults: 2022 Recommendations from an International Expert Panel on Behalf of the ELN. Blood. 2022;140:1345–1377. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022016867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duncavage EJ, Bagg A, Hasserjian RP, DiNardo CD, Godley LA, Iacobucci I, Jaiswal S, Malcovati L, Vannucchi AM, Patel KP, et al. Genomic Profiling for Clinical Decision Making in Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemia. Blood. 2022;140:2228–2247. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022015853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molica M, Perrone S. Molecular Targets for the Treatment of AML in the Forthcoming 5th World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours. Expert Review of Hematology. 2022;15:973–986. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2022.2140137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, Thirman MJ, Garcia JS, Wei AH, Konopleva M, Döhner H, Letai A, Fenaux P, et al. Azacitidine and Venetoclax in Previously Untreated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:617–629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cortes JE, Heidel FH, Hellmann A, Fiedler W, Smith BD, Robak T, Montesinos P, Pollyea DA, DesJardins P, Ottmann O, et al. Randomized Comparison of Low Dose Cytarabine with or without Glasdegib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia or High-Risk Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Leukemia. 2019;33:379–389. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0312-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiNardo CD, Tiong IS, Quaglieri A, MacRaild S, Loghavi S, Brown FC, Thijssen R, Pomilio G, Ivey A, Salmon JM, et al. Molecular Patterns of Response and Treatment Failure after Frontline Venetoclax Combinations in Older Patients with AML. Blood. 2020;135:791–803. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molica M, Mazzone C, Niscola P, Carmosino I, Di Veroli A, De Gregoris C, Bonanni F, Perrone S, Cenfra N, Fianchi L, et al. Identification of Predictive Factors for Overall Survival and Response during Hypomethylating Treatment in Very Elderly (≥75 Years) Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients: A Multicenter Real-Life Experience. Cancers. 2022;14:4897. doi: 10.3390/cancers14194897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouligny I, Murray G, Ho T, Gor J, Zacholski K, Wages N, Grant S, Maher K. The Impact of Delayed Venetoclax Initiation on Overall Survival in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood. 2023;142:4233–4233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2023-188249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]