Abstract

Immune thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (iTTP) is a life-threatening thrombotic microangiopathy characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and ischemic end-organ injury due to microvascular platelet-rich thrombi. iTTP pathophysiology is based on a severe ADAMTS13 deficiency, the specific von Willebrand factor (vWF)-cleaving protease, due to anti-ADAMTS13 autoantibodies. Early diagnosis and treatment reduce the mortality. Frontline therapy includes daily plasma exchange (PEX) with fresh frozen plasma replacement and immunosuppression with corticosteroids. Caplacizumab has recently been added to frontline therapy. Caplacizumab is a nanobody that binds to the A1 domain of vWF, blocking the interaction of ultra-large vWF multimers with the platelet and thereby preventing the formation of platelet-rich thrombi. Caplacizumab reduces mortality due to ischemic events, refractoriness, and exacerbations after PEX discontinuation. Until now, the criteria for response to treatment mainly took into account the normalization of platelet count and discontinuation of PEX; with the use of caplacizumab leading to rapid normalization of platelet count, it has been necessary to redefine the response criteria, taking into account also the underlying autoimmune disease. Monitoring of ADAMTS13 activity is important to identify cases with a low value of activity (<10IU/L), requiring the optimization of immunosuppressive therapy with the addition of Rituximab. Rituximab is effective in patients with refractory disease or relapsing disease. Currently, the use of Rituximab has expanded, both in frontline treatment and during follow-up, as a pre-emptive approach. Some patients do not achieve ADAMTS13 remission following the acute phase despite steroids and rituximab treatment, requiring an individualized immunosuppressive approach to prevent clinical relapse. In iTTP, there is an increased risk of venous thrombotic events (VTEs) as well as arterial thrombotic events, and most occur after platelet normalization. Until now, there has been no consensus on the use of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis in patients on caplacizumab because the drug is known to increase bleeding risk.

Keywords: Caplacizumab, Rituximab, Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP)

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old man was hospitalized for dysarthria and confusion. Contrast-enhanced brain CT excluded cerebrovascular events, while blood routine tests showed normocytic anemia 7.8 g/dL with 14% schistocytes, thrombocytopenia 10x109/L, total bilirubin 2.8 mg/dL (indirect 2.5 mg/dl) lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 1500 units/L and elevated Troponin 75.5 pg/mL without ECG abnormalities. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) was suspected, and PLASMIC SCORE demonstrated high risk at 7 points. The patient was started on daily plasmapheresis (PEX), steroids (1 mg/kg methylprednisolone), and Caplacizumab. ADAMST13 level was later confirmed to be less than 3 IU/dl with anti-ADAMTS13 autoantibodies >80 U/ml. PEX was performed for 7 consecutive days, with complete recovery of neurological symptoms, platelet counts, and haptoglobin levels, so the patient was discharged on self-administered Caplacizumab and steroids. Five days after the last PEX, the planned monitoring of ADAMTS13 activity was still <3 IU/dl, and the patient showed a drop in platelet counts to 60x109/L associated with signs of microangiopathy. Therefore, PEX was resumed, and Rituximab (375 mg/mq) was added to the ongoing treatment, with fast platelet recovery. After the second dose of Rituximab, we observed a new episode of aphasia/dysarthria and confusion, but this time, Brain-MRI was consistent with recent ischemic cerebral lesions. In view of the onset of an acute cerebrovascular event, although platelet count was slowly increasing but not yet in the normal range, we considered it necessary to increase the anti-aggregating therapy by adding ASA 100 mg/day. However, we were afraid to administer it together with caplacizumab, which was suspended while the rest of the ongoing treatment was continued. After a rise in platelet counts, up to 150x109/L PEX was withheld, and steroids were quickly tapered. Ten days later, after the third rituximab dose, a new fall in platelets count without signs of microangiopathy was observed. Since ADAMTS13 activity was 60 IU/dl and ADAMTS13 autoantibodies were not detectable, we investigated for further causes of thrombocytopenia, such as decreased bone marrow production, consumption processes, and infections. The diagnostic work-up showed 150.000 gene copies/ml of blood-CMV-DNA. Antiviral therapy with IV Ganciclovir (5 mg/kg BID) was started, and a progressive normalization of platelet count was documented.

What is the appropriate management of iTTP? What are the criteria for defining refractory disease in the caplacizumab era? What is the most appropriate time to add Rituximab? Is administration of caplacizumab and antiplatelets or anticoagulant therapy safe? Are all the drops in platelets count as a sign of iTTP refractory or exacerbation?

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a rare and life-threatening thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), first described in 1924 by Dr. Eli Moschcowitz.1 This disease has an annual incidence of 1.5–6 per million cases in adults2,3 and is characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA), thrombocytopenia, and organ failure of variable severity.4 In patients with TTP, the levels of the von Willebrand factor (VWF)-cleaving protease ADAMTS13 are severely decreased. Acquired immune-mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (iTTP) is caused by the development of anti-ADAMTS13 autoantibodies targeting ADAMTS13, resulting in a lowered ADAMTS13 function or an increase in the metalloprotease’s clearance.5

TTP is a medical emergency with life-threatening complications and a 90% mortality rate if left untreated.

Pathophysiology

Progress has been made in recent years in understanding the pathophysiology of the disease. ADAMTS13 is the 13th member of the ADAMTS protein family identified for the first time in 2001.6 It is a metalloprotease that cleaves the ultra-large vWF multimers secreted by Weibel-Palade bodies of endothelial cells and α-granules of platelets linked to the endothelium. Arterial shear-stress and reciprocal interaction induce a change in both vWF and ADAMTS13 conformations that allow ADAMTS13 to cleave vWF into smaller and less adhesive multimers.7–10 Hence, severe ADAMTS13 deficiency (< 10 IU/dl) leads to the accumulation of unusually ultra-large vWF multimers in the bloodstream and subsequent platelets adhesion, agglutination, and formation of occlusive thrombi in small arterioles and capillaries, inducing widespread microvascular ischemia.11,12

Nevertheless, a severe enzyme deficiency is necessary, but not sufficient on its own to cause an episode of TTP. It has been suggested that another stressor factor in conjunction with this severe deficiency is usually required to develop a clinical evident TTP, such as activation of the complement system.13–15

Anti-ADAMTS13 autoantibodies can be divided into two groups: inhibitory and non-inhibitory. Inhibitory antibodies neutralize the proteolytic activity of the enzyme, while non-inhibitory antibodies accelerate its clearance from plasma by binding to the protease and increasing its uptake by the reticular endothelial system (RES).16,17 Even if inhibitory antibodies have always been considered the major cause of ADAMTS13 deficiency, recent studies have proved that antigen depletion plays an important role in this deficiency.18 Immune TTP is characterized by a polyclonal immune response, as proven by the fact that autoantibodies have been found against all domains of ADAMTS13.19,20 However, the spacer domain is the most frequently involved with autoantibodies directed against it in 95% of cases.21

The most common isotype class of anti-ADAMT13 autoantibodies is IgG, but IgA and IgM have been reported as well (20% of cases). Among the IgG isotype, the IgG4 subclass is most frequent, followed by IgG1.22–24 The autoantibody isotype may contribute to the disease’s clinical phenotype; for example, IgA and IgG1 antibodies are associated with a higher death rate and IgG4 with an increased risk of relapse.22–24 In addition to free anti-ADAMTS13 autoantibodies, circulating ADAMTS13-specific immune complexes have also been reported during acute iTTP.25–27 These complexes may lead to complement activation; in fact, during an acute iTTP episode, it has been found that C3a and C5a are elevated, suggesting a complement activation through the classic pathway; nevertheless, elevated levels of factor Bb have been detected, evoking activation of the alternative pathway.13–15,21,28 Complement activation in TTP may play the role of the “second hit”, acting as another stressor in combination with severe ADAMTS13 deficiency to induce the clinical syndrome.15 Molecular mimicry between ADAMTS13 and certain pathogens infection might be considered one of the triggers to evoke an immune response, although no bacterial or viral infections are directly linked with iTTP.21,29–33 Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection can also be considered a possible trigger of TTP and may cause refractoriness at iTTP treatment.34 COVID-19 infection has been associated with endotheliopathy, and it is also associated with TTP. Recently, de novo and relapsed iTTP have been reported during SARS-Cov-2 infection.35 Cases of iTTP following the administration of vaccines have been described in the literature.36–37 Recently, de novo and relapsed iTTP have been reported after COVID-19 vaccination, mainly with adenoviral and rarely with mRNA vaccines.38–39 Some studies have investigated the possible correlation between COVID-19 vaccines and the iTTP new onset or recurrence. Results showed that COVID-19 vaccination does not increase the risk of de novo or relapsed iTTP, except in individuals in hematologic remission with extremely low ADAMTS13 activity (<20%), requiring closer monitoring in these patients.40–43

Clinical Manifestation and Diagnosis

The TMA syndromes (TMAs) are a group of different diseases united by common clinical and pathological features. They occur in children or in adults. The clinical manifestations include microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and organ damage. Although they are different entities, they have in common a pathogenic mechanism involving endothelial injury and thrombus formation. Therefore, laboratory tests are important alongside a thorough history and examination. Prognosis and treatment depend on the nature of the underlying disease. In TTP and Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (HUS), there is an underlying abnormality, such as ADAMTS13 deficiency or a complement mutation, that may not be clinically expressed until pregnancy, surgery, or an inflammatory disorder precipitates an acute TMA episode. The treatment, in these patients, is focused on the cause of the primary TMA syndrome, not the precipitating condition. These patients are distinct from many other patients who have microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia that are manifestations of an underlying disorder, such as systemic infections, systemic cancer, severe preeclampsia or HELLP syndrome, severe hypertension, autoimmune disorders and hematopoietic stem cell or organ transplantation. The treatment of such patients is focused on the underlying disorder. A thorough diagnostic evaluation will usually reveal the underlying etiology and guide treatment. As many of the investigations will not be available at the initial presentation, the initial focus should be on the consideration of TTP, given the high mortality if untreated. The ADAMTS13 activity test should be applied to any diagnosis of thrombotic microangiopathy.

Anemia with schistocytes >1%, elevated serum LDH, reticulocyte count, total bilirubin, predominantly unconjugated, decreased haptoglobin, thrombocytopenia, and microvascular ischemia are the typical clinical manifestations in TMAs. Direct and indirect antiglobulin tests are negative, and coagulation parameters are normal. In TTP, although all organs can be affected, central nervous system, heart, and digestive tract involvement are more frequent. Conversely, renal damage is usually mild, in contrast to other forms of TMA, such as HUS. Signs and symptoms are variable at presentation. More than 60% of cases present with neurological manifestations, which widely range from mild confusion or altered sensorium to headache, transient focal brain defect, stroke, seizures, or coma.2,3,44 Abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea are due to gastrointestinal ischemia, which can be evident in 35% of patients.3 Evidence of myocardial ischemia highlighted either by an abnormal electrocardiogram or, more commonly, by elevated cardiac troponin-I measurements can be found in around a quarter of acute TTP patients. Most frequently, this myocardial ischemia is asymptomatic. Benhamou et al. have found that even if asymptomatic, a cardiac troponin-I (CTnI) level of < 0.25 μg/L at presentation in patients with TTP appears to be an independent factor associated with a three-fold increase in the risk of death or refractoriness.45 Renal injury is not uncommon in iTTP. Hence, most patients present with creatinine below 2 mg/dL.3,46 The main causes of morbidity and mortality in iTTP are thrombotic and ischemic complications.

Early diagnosis and treatment reduce the mortality rate, which, however, remains around 10–15%.47 Severe deficiency of ADAMTS13 activity (<10 IU/dl) with detectable inhibitory autoantibodies against ADAMTS13 confirms the diagnosis. Due to the rarity of TTP, ADAMTS13 assays are not widely performed and remain mainly confined to specialized laboratories, therefore, the initial diagnosis is a clinical diagnosis.48 Scoring systems developed using data from TMA registries, such as the French score and Plasmic score,49–51 may help decide on the urgency of ADAMTS13 testing and the likelihood of a positive TTP diagnosis. The PLASMIC and French scores turned out to be useful predictors of a significant reduction in ADAMTS13 activity, and in the high-risk group (scores 6–7) of the PLASMIC score (Table 1), patients who received treatment had meaningfully higher overall survival than those who did not. However, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that the PLASMIC score can support differential diagnosis by excluding TTP, but due to low specificity and positive predictive value, it is insufficient to confirm TTP diagnosis.52 Older iTTP patients have an atypical clinical presentation and a poorer response to treatment and prognosis. Renal and cardiac involvement are more frequent and severe in older patients, whereas hematologic features such as thrombocytopenia and anemia are less pronounced. These differences translate into poorer performances of both the French and PLASMIC scores.53

Table 1.

Predictive score for severe ADAMTS13 deficiency in suspected TTP.

| Plasmic Score | French Score | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Platelet count | <30x109/L (+1) | <30x109/L (+1) |

| Serum creatinine level | <2.0 mg/dl (+1) | <2.26 mg/dl (+1) |

| Hemolysis | (+1) | - |

| Indirect bilirubin>2 mg/dl | ||

| Or reticulocyte count>2.5% | ||

| Or undetectable haptoglobin | ||

| No active cancer in previous year | (+1) | - |

| No history of solid organ or stem cell transplant | (+1) | - |

| INR<1.5 | (+1) | - |

| MCV<90fL | (+1) | - |

| Likelihood of severe ADAMTS13 deficiency (ADAMTS13 activity<10%) | ||

| Low risk | 0–4: 0–4% | 0: 2% |

| Intermediate risk | 5: 5–24% | 1: 70% |

| High risk | 6–7: 62–82% | 2: 94% |

INR: international normalized ratio, MCV: mean corpuscular value.

Hence, ADAMTS13 activity measurement remains necessary for an accurate differential diagnosis and management of TTP.

Management of Acute Phase

When a TTP is suspected, the patient’s blood sample for ADAMTS13 activity testing should be collected immediately, but treatment must be initiated before the result is available. According to the ISTH guidelines, the results of ADAMTS13 activity should ideally be available within 72 hours, though a result within seven days is acceptable.54 Prompt initiation of therapy reduces mortality to 10–15%.

Until recently, the standard treatment of acute iTTP consisted of daily therapeutic plasma exchange (PEX) and immunosuppressive therapy. In 1991, the Canadian randomized clinical trial documented the effectiveness of PEX over plasma infusion alone.55 However, in situations where PEX cannot be quickly performed, plasma infusion may be used temporarily as a temporizing measure.56 PEX removes anti-ADAMTS13 antibodies and replaces ADAMTS13. It should be initiated as soon as possible and not later than 6 hours of presumptive clinical diagnosis.57 The expert panel suggests one PEX session daily; the usual volume for exchange is 40 ml/kg (1 plasma volume), but in patients with severe disease, such as those with neurological manifestations or who do not readily respond to treatment, the PEX volume can be increased to 60 ml/kg (1.5 plasma volume), or PEX may be performed more than once daily. According to 2022 guidelines, PEX may be discontinued soon after a clinical response, defined by a sustained platelet count ≥150x109/L and LDH <1.5 times the upper limit of normal and no clinical evidence of new or progressive ischemic organ injury, is achieved.58

Corticosteroid therapy is commonly used in conjunction with PEX to suppress the production of anti-ADAMTS13 autoantibodies.54,57 Although the corticosteroid dosage, dose adjustment, or tapering were not well determined in randomized clinical trials, high-dose corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone, 1 mg/kg per day, orally, or methylprednisolone, 125 mg, IV, two to four times) are usually used as the initial regimen. Balduini et al. compared high-dose methylprednisolone (10 mg/kg/day for 3 days followed by 2.5 mg/kg/day) to standard dose methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) and found that remission rates were significantly higher in the high dose group (76.6% vs. 46.6%).59 Therefore, high-dose steroids bolus with methylprednisolone may be used as the first-line, especially in patients with severe presentations or neurological symptoms.59

Anti-vWF therapy with caplacizumab was recently approved for the initial treatment of iTTP in conjunction with PEX and steroids. Caplacizumab is a nanobody (a bivalent humanized immunoglobulin fragment) that binds to the A1 domain of vWF, blocking the interaction of ultra-large vWF multimers with the platelet GpIb-IX-V receptor and thereby preventing the formation of platelet-rich thrombi.60 The current ISTH guidelines recommend its use in acute iTTP because immunosuppressive therapy requires a certain period to obtain a response, and fatal thrombosis is very common in the first 10 days after diagnosis.54 Caplacizumab is started at 10 mg intravenously immediately after diagnosis, followed by 10 mg subcutaneously (s.c.) after each PEX, and subsequently followed by daily s.c. injections until stable recovery of ADAMTS13 activity > 10–20 IU/dl. Its efficacy and safety have been demonstrated in two randomized controlled trials: the phase II (TITAN) and phase III (HERCULES) studies.61–62 In the integrated analysis of data from both trials, a significant reduction in the number of deaths (0 vs. 4; P <0.05) and a significantly lower incidence of refractory TTP (0 vs. 8; P <0.05) were observed in patients who received caplacizumab versus placebo.63 Also, caplacizumab significantly reduced the time to platelet count normalization (P < .001), significantly reduced the time to normalization of the organ damage marker LDH (P .03) and induced a faster normalization of troponin and serum creatinine. During the overall treatment period, there was a 33.3% reduction in the median number of PEX days with caplacizumab vs placebo (5.0 days vs 7.5 days, respectively). The trials also demonstrated a reduction in hospital and ICU length of stay. The most common adverse event associated with caplacizumab was mucocutaneous bleeding. However, these events were mild or moderate in severity and resolved spontaneously in most patients.

Recent studies provide real-world data on the efficacy and safety of caplacizumab, confirming its therapeutic benefits when used as initial treatment. The time to platelet count normalization and clinical remission was much shorter among patients who received caplacizumab within 3 days of the first PEX, and the early prevention of microcirculation occlusion and ischemic organ damage seemed to avoid long-term complications and eventually death.64–68

Caplacizumab is an expensive drug, but the costs are balanced by reduced hospitalization and long-term effects. It has been described that patients with TTP in the pre-caplacizumab era, in the long run, suffer from disabling conditions related to cerebral microthrombosis.69

Our patient, based on clinical suspicion, was treated with PEX, steroids, and caplacizumab, achieving improvement of neurological symptoms and normalization of platelet count. Seven PEX were performed, and then the patient was discharged, continuing home steroids and caplacizumab. Five days after the last PEX, a reduction in platelet count was noted. This event is possible during caplacizumab administration but is not frequent. Training had been performed to teach her the correct administration of caplacizumab at home. However, we do not know whether the patient was compliant with the dosing and administration, and no anti-vWF tests were performed to demonstrate the caplacizumab activity.70 Plasma ADAMTS13 activity was less than 3 IU/dl, and ADAMTS13 autoantibodies were still present. Therefore, PEX was resumed, and immunosuppressive treatment was intensified with the addition of Rituximab.

In registration trials, more relapses occurred with caplacizumab compared with placebo (14 vs 0 participants) and occurred within 10 days of stopping caplacizumab in patients with persistent ADAMTS13 levels <10 IU/dl, highlighting the importance of monitoring weekly ADAMTS13 activity and continuing caplacizumab treatment until resolution of the underlying autoimmune disease, possibly optimizing immunosuppressive therapy.61–62 An ADAMTS13 threshold above which anti-vWF therapy can be safely discontinued remains to be defined, although a level that is increasing >20 IU/dl for at least 2 consecutive weeks has been suggested.71 In the recently reported German post-marketing experience with caplacizumab, there were no iTTP recurrences when the drug was discontinued in patients with ADAMTS13 activity >10 IU/dl.72

Until now, the criteria for response to treatment mainly took into account the normalization of platelet count and discontinuation of PEX. Now, with the use of caplacizumab, leading to rapid normalization of platelet count, it has been necessary to redefine the response criteria, taking into account also the underlying autoimmune disease. Therefore, the International Working Group for TTP proposed revised consensus outcome definitions that incorporate ADAMTS13 activity and the effects of anti-VWF therapy on the platelet count, by using an estimate-talk-estimate approach.73 The updated definitions distinguish clinical remission and clinical relapse, defined primarily by platelet count, from ADAMTS13 remission and ADAMTS13 relapse, defined by ADAMTS13 activity. The IWG defines clinical remission as a sustained clinical response with both no TPE and no anti-vWF therapy in the past 30 days. Clinical exacerbation occurs when the platelet count decreases to < 150x109/L (with other causes of thrombocytopenia excluded), with or without clinical evidence of new or progressive ischemic organ injury, within 30 days of stopping PEX or anti-vWF therapy. Refractory TTP is used to describe cases where there is no clinical response after five sessions of PEX or there is an initial response followed by a platelet decline while receiving standard treatment and requires early intensified treatment. Partial ADAMTS13 remission as ADAMTS13 activity >20 UI/dl but less than the lower limit of normal (LLN) and complete ADAMTS13 remission as ADAMTS13 activity >= LLN.73

Due to biological variability in ADAMTS13 activity, it is important to repeat the measurement to confirm ADAMTS13 activity, relying more on the trend than on a specific value.

Some patients may achieve clinical remission without ADAMTS13 remission; therefore, the risk of clinical relapse is very high in these patients, so it is important to optimize immunosuppressive therapy to avoid recurrence.

Platelet transfusions are usually avoided in TTP. However, platelet transfusions are sometimes used in TTP patients with serious bleeding or in TTP patients undergoing invasive procedures with a high risk of bleeding.74

Rituximab Treatment

Rituximab is a chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody. It suppresses anti-ADAMTS13 antibody production by depleting B lymphocytes via complement-dependent cytotoxicity and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Rituximab is effective in patients with refractory disease whose platelet counts do not recover despite conventional therapy and in those with early relapsed disease. The usual dosage is 375 mg/m2 once a week for four weeks, modifying the schedule from weekly to every 3–4 days in case of concurrent PEX treatment considering the accelerated clearance.75 In refractory patients, Rituximab can normalize platelet count early and prevent short-term relapse.76 Currently, the use of Rituximab has expanded, both in front-line treatment and as a pre-emptive approach in patients in clinical remission but having low ADAMTS13 levels.

In 2011, the UK group reported in a prospective trial that front-line treatment with Rituximab administered within three days of admission resulted in shorter hospitalization and fewer relapses (10% vs >50% in historical controls) and was well-tolerated.77 This study provided evidence for the benefits of Rituximab as initial therapy, showing a high remission rate in patients who received the standard therapy, with nearly half of the patients not relapsing. Therefore, Rituximab may be suitable as a first-line treatment of iTTP for some patients; however, a subgroup of patients may receive unnecessary treatment.

A recent meta-analysis also suggests the benefit of upfront Rituximab, which documented that its use reduces mortality and prevents relapse.78 However, the study has some limitations because none of the included studies was a randomized trial.

In a recent study, Coppo et al. treated 90 iTTP patients with a frontline triplet regimen associating PEX, immunosuppression with corticosteroids and Rituximab, and caplacizumab. Outcomes were compared with 180 historical patients treated with the standard frontline treatment (PEX and corticosteroids, with Rituximab as salvage therapy). Patients from the triplet regimen experienced fewer exacerbations (3.4% vs. 44%, P < .01); they recovered durable platelet count 1.8 times faster than historical patients (P < .01), with fewer PEX sessions (P < .01) and the number of days in hospital was 41% lower in the triplet regimen than in the historical cohort (13 vs 22 days; P < .01). In addition, the use of Rituximab in frontline resulted in more rapid improvement in ADAMTS13 activity (>20 IU/dl) than the historical regimen in which Rituximab was introduced only later as salvage therapy, with a mean of 28 days compared with 48 days (P .01).68

To date, however, the use of Rituximab in the frontline remains controversial, and the ISTH guidelines suggest that Rituximab should be used as part of the first-line treatment of severe TTP, recommending Rituximab in the frontline therapy for only selected cases such as patients with comorbid autoimmune disorders due to low levels of evidence.54

Monitoring ADAMTS13 activity could help identify those patients who do not have an optimal response to immunosuppressive treatment with steroids as they maintain a low value of activity (<10 IU/dl) after at least three weeks of steroid treatment.

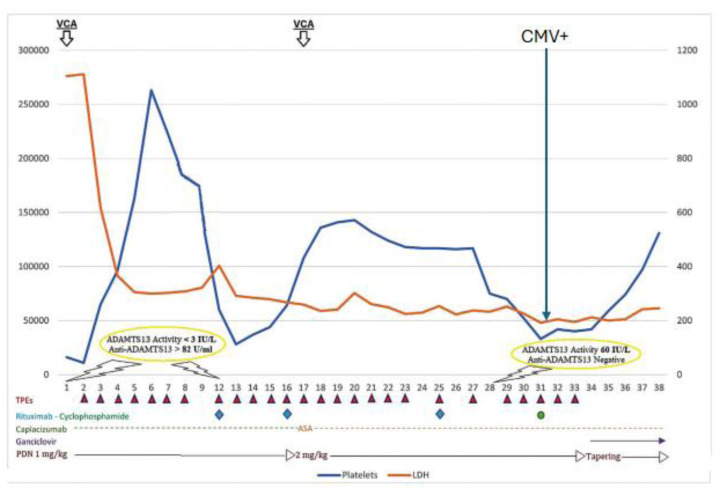

Increasing immunosuppression in cases with refractory iTTP or in those without normalization of ADAMTS13 activity may expose patients to opportunistic viral or bacterial infections. A literature review of viral infections after Rituximab conducted by Aksov et al. showed that hepatitis B virus infection was the most common infection observed in 39% of the cases. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection was observed in 23% of the cases; CMV usually is a latent infection and gets reactivated during an immunocompromised state.79 Thrombocytopenia, due to CMV reactivation, may mimic an iTTP exacerbation as described by Laganà et al. (Figure 1).80 Therefore, early identification of CMV is essential for the successful treatment of refractory/relapsed iTTP or a false iTTP exacerbation to avoid CMV complications.

Figure 1.

Adapted from Laganà et Al. Blood Coagulation and Fibrinolysis 2024, 35:37–42.

Platelet (PLT), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Blue line: PLT count. Orange: LDH levels. ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; PDN, prednisone; TPE, therapeutic plasma exchange; VCA, cerebrovascular accident; CMV, Cytomegalovirus. During the third platelet drop, days 27–34, the ADAMS 13 was high, CMV was positive, and Ganciclovir was added.

In our patient, a second fall in platelet count was not associated with signs of hemolysis. Since the ADAMTS13 activity was normal, we looked for secondary causes that could explain the reduction in platelet count. Cytomegalovirus infection was documented and responsive to antiviral treatment.

Additional Immunosuppressive Agents

Some patients do not achieve ADAMTS13 remission following the acute phase despite steroids and rituximab treatment, requiring an individualized immunosuppressive approach to prevent clinical relapse. Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or azathioprine are both used in the treatment of autoimmune diseases by modulating the immune system with suppression of B and T lymphocyte proliferation and antibody production.81–82 Cyclosporin A has been used to treat relapsed and refractory iTTP with recovery of ADAMTS13 activity and reduction of antibody levels, suggesting a role in patients with disease recurrence.83–84 Cyclophosphamide was utilized as salvage therapy for refractory/relapsed patients.85

In patients unable to receive Rituximab due to severe allergic reactions, alternative anti-CD 20 therapy (including ofatumumab or obinutuzumab) has also been used.86–87 Finally, in some cases where patients do not have an adequate response to anti-CD20 therapy, other immunomodulating agents (such as bortezomib or daratumumab) can be considered.88–89

Caplacizumab and Thromboprophylaxis

In iTTP, there is an increased risk of venous and arterial thrombotic events (VTEs). VTE rates range from 3.8% to 13%, and most VTEs occur after platelet normalization, especially in patients who do not receive thromboprophylaxis.90

The effect of caplacizumab on the risk of VTE is unclear. In real-world studies, the risk of VTE was similar between caplacizumab and control groups, suggesting that caplacizumab was not effective in preventing VTE.91,68 There is no consensus on the use of pharmacological thromboprophylaxis in patients on caplacizumab because the drug is known to increase bleeding risk, so co-administration with antiplatelets or anticoagulant drugs may lead to major bleeding. In the recent ISTH guidelines for the treatment of TTP, no recommendations on antithrombotic use either with or without caplacizumab are included, and there is no statement to withhold or continue caplacizumab in case of adding an antithrombotic agent due to a new thrombotic event.54

When our patient presented a second episode of aphasia, dysarthria, and confusion, although there were no signs of cerebral hemorrhage, in order to treat the new ischemic event, we preferred not to administer caplacizumab together with acetylsalicylic acid not to increase the hemorrhagic risk. Recently, Elverdi et al. published a review focusing on the thrombotic complications and bleeding events observed in TTP patients both in the pre- and post-capacizumab era.92 They suggest that, in the absence of clinical indication, concomitant use of caplacizumab and antiplatelet drugs should not be encouraged. However, if strongly indicated, they can be used concomitantly safely, yet careful monitoring is mandatory. When the platelet counts are <50 x 109/L, the indication could be assessed on a patient-by-patient basis by weighing the risk of hemorrhage vs. thrombosis.

TTP in Remission

After complete remission, the risk of relapse is between 30 to 50%, exposing patients to death and treatment-related complications.93 It has been reported that persistently undetectable ADAMTS13 activity (<10 IU/dl) in patients in remission represents an early predictor of clinical relapse and that the cumulative incidence of relapse increases dramatically with time (74% at 7 years).94 Therefore, long-term monitoring of ADAMTS13 activity is necessary during follow-up. In patients in remission, ADAMTS13 activity testing is usually scheduled every month for the first 3 months, then every 3 months for the first year, then every 6–12 months if stable, and more frequently if levels begin to drop. It has been shown that pre-emptive rituximab infusions in patients with persistently undetectable ADAMTS13 activity or when the activity falls from normal levels to <20 IU/dl allow, in most cases, the rapid recovery of ADAMTS13 activity.95–97 However, this recovery may not be sustained, and a substantial number of patients require repeated rituximab infusions to maintain a detectable enzyme activity over time. Consequently, the systematic pre-emptive use of Rituximab in this setting is still debated.98

In a recent retrospective study, the French TMA group reported the long-term outcome of 92 patients with iTTP in clinical remission who received pre-emptive Rituximab after identification of severe ADAMTS13 deficiency (activity <10 IU/dl) during the follow-up and presented an improved relapse-free survival, compared with a historical control of patients.99 There was no increased incidence of adverse effects with long-term use of Rituximab and no loss of response with repeated courses. Dosing regimens, apart from the standard weekly 375 mg/m2 dose, have been used, ranging from 100 mg to 500 mg/m2 weekly with 1 o 2 o 4 infusions per course. They found that half of the patients treated with pre-emptive Rituximab required repeated courses for subsequent recurrences of ADAMTS13 relapses, and retreated patients usually responded again to Rituximab. However, they observed that the interval between treatments was twice as long after a preemptive course of 4 infusions compared with a course with 1 or 2 infusions. Retrospective evidence suggests that although low-dose Rituximab (200 mg x4 weekly) prevents iTTP relapses, it is associated with higher re-treatment rates than the standard dose.96

Also, whereas an ADAMTS13 level of >20 IU/dl < ULN may be sufficient to prevent iTTP relapse, it may not be sufficient to prevent other adverse clinical outcomes. Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated that, among patients with a history of iTTP who are in clinical remission, those with a partial ADAMTS13 remission are at greater risk of ischemic stroke than those with a complete ADAMTS13 remission.100 A recent study showed that a subgroup of anti-ADAMTS13 autoantibodies from iTTP patients can induce an open ADAMTS13 conformation. Most importantly, an open ADAMTS13 conformation is present in acute iTTP patients and in those in clinical remission with decreased ADAMTS13 activity <50 IU/dl. Therefore, open ADAMTS13 may become a novel and sensitive biomarker to monitor iTTP patients and identify the early stages of subclinical iTTP, but further investigation is warranted.101

Finally, in patients who have recovered from an acute TTP episode, the Guideline panel acknowledged the importance of monitoring for the development of mood disorders, neurocognitive symptoms (including short-term memory issues), and hypertension, which may develop during remission. Specific recommendations regarding screening for long-term complications cannot be made at this time. However, serial follow-up and monitoring for these complications should be considered part of routine follow-up.97

The Future: Recombinant Adamts13

Another novel therapy currently under investigation in clinical trials is recombinant ADAMTS13 (BAX930/SHP655/TAK755).102 A Phase II trial is assessing the role of rADAMTS13 in treating acute presentations of iTTP in addition to standard care (NCT03922308). The potential inhibitory effect of autoantibodies on the recombinant ADAMTS13 will need to be evaluated.

Concluding Remarks

Major advances in iTTP pathophysiology and management have occurred over the last few decades, leading to a significant improvement in patient outcomes. Early diagnosis and improved therapeutic management have reduced mortality and prolonged survival. Plasma exchange and immunosuppressive therapy remain the standard treatments.

Caplacizumab reduces mortality due to ischemic events, refractoriness, and exacerbations after treatment discontinuation; for maximum efficacy, it should be started as early as possible with the first PEX.

However, there are still open issues. When can the PEX be discontinued with the use of caplacizumab, which induces rapid normalization of platelet count, whether sufficient to rely only on platelet count?

Close monitoring of ADAMTS13 activity after platelet recovery can guide in optimizing immunosuppressive therapy with Rituximab, although rituximab treatment in combination with steroids may induce opportunistic infections such as pneumocystis infections or viral infections (CMV or hepatitis). Such infections may also mimic an exacerbation of TTP.

In case of ischemic events or VTE, concomitant administration of caplacizumab and antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy is not encouraged but can be done very cautiously if necessary.

Targeted immune treatments should be performed in remission to reduce relapses during follow-up.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no conflict of Interest.

Author Contributions: SMT and AL wrote and edited the manuscript. SC revised and corrected the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Moschcowitz E. Hyaline Thrombosis of the Terminal Arterioles and Capillaries: A Hitherto Undescribed Disease. Proc N Y Pathol Soc. 1924;24:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scully M, Yarranton H, Liesner R, Cavenagh J, Hunt B, Benjamin S, Bevan D, Mackie I, Machin S. Regional UK TTP registry: Correlation with laboratory ADAMTS 13 analysis and clinical features. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:819–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mariotte E, Azoulay E, Galicier L, Rondeau E, Zouiti F, Boisseau P, Poullin P, de Maistre E, Provôt F, Delmas Y, et al. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of adulthood-onset thrombotic microangiopathy with severe ADAMTS13 deficiency (thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura): A cross-sectional analysis of the French national registry for thrombotic microangiopathy. Lancet Haematol. 2016;3:e237–e245. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(16)30018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amorosi EL, Ultmann JE. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic Purpura: report of 16 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1966;45:139–60. doi: 10.1097/00005792-196603000-00003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George JN, Nester CM. Syndromes of thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2014 Aug 14;371(7):654–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1312353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy GG, Nichols WC, Lian EC, et al. Mutations in a member of the ADAMTS gene family cause thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Nature. 2001;413(6855):488–494. doi: 10.1038/35097008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.South K, Luken BM, Crawley JTB, et al. Conformational activation of ADAMTS13. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(52):18578–18583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411979112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muia J, Zhu J, Gupta G, et al. Allosteric activation of ADAMTS13 by von Willebrand factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(52):18584–18589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413282112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deforche L, Roose E, Vandenbulcke A, et al. Linker regions and flexibility around the metalloprotease domain account for conformational activation of ADAMTS-13. J Thromb Haemost JTH. 2015;13(11):2063–2075. doi: 10.1111/jth.13149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawley JTB, de Groot R, Xiang Y, et al. Unraveling the scissile bond: how ADAMTS13 recognizes and cleaves von Willebrand factor. Blood. 2011;118(12):3212–3221. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-306597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadler JE. What’s new in the diagnosis pathophysiology of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Hematol Educ Program Am Soc Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015:631–636. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furlan M, Robles R, Galbusera M, et al. von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(22):1578–1584. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811263392202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Réti M, Farkas P, Csuka D, Rázsó K, Schlammadinger Á, Udvardy ML, Madách K, Domján G, Bereczki C, Reusz GS, et al. Complement activation in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Thromb Haemost. 2012:791–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner N, Sartain S, Moake J. Ultralarge von Willebrand factor-induced platelet clumping and activation of the alternative complement pathway in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and the hemolytic-uremic syndromes. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2015;29:509–524. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyata T, Fan X. A second hit for TMA. Blood. 2012;120:1152–1154. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-433235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scheiflinger F, Knöbl P, Trattner B, Plaimauer B, Mohr G, Dockal M, Dorner F, Rieger M. Nonneutralizing IgM and IgG antibodies to von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease (ADAMTS-13) in a patient with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2003;102:3241–3243. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rieger M, Mannucci PM, Kremer Hovinga JA, Herzog A, Gerstenbauer G, Konetschny C, Zimmermann K, Scharrer I, Peyvandi F, Galbusera M, et al. ADAMTS13 autoantibodies in patients with thrombotic microangiopathies and other immunomediated diseases. Blood. 2005;106:1262–1267. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas MR, de Groot R, Scully MA, Crawley JT. Pathogenicity of Anti-ADAMTS13 Autoantibodies in Acquired Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:942–952. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng XL, Wu HM, Shang D, Falls E, Skipwith CG, Cataland SR, Bennett CL, Kwaan HC. Multiple domains of ADAMTS13 are targeted by autoantibodies against ADAMTS13 in patients with acquired idiopathic thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Haematologica. 2010;95:1555–1562. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.019299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamaguchi Y, Moriki T, Igari A, Nakagawa T, Wada H, Matsumoto M, Fujimura Y, Murata M. Epitope analysis of autoantibodies to ADAMTS13 in patients with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Thromb Res. 2011;128:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verbij FC, Fijnheer R, Voorberg J, et al. Acquired TTP: ADAMTS13 meets the immune system. Blood Rev. 2014;28(6):227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrari S, Scheiflinger F, Rieger M, Mudde G, Wolf M, Coppo P, Girma JP, Azoulay E, Brun-Buisson C, Fakhouri F, et al. Prognostic value of anti-ADAMTS 13 antibody features (Ig isotype, titer, and inhibitory effect) in a cohort of 35 adult French patients undergoing a first episode of thrombotic microangiopathy with undetectable ADAMTS 13 activity. Blood. 2007;109:2815–2822. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-006064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrari S, Mudde GC, Rieger M, Veyradier A, Kremer Hovinga JA, Scheiflinger F. IgG subclass distribution of antiADAMTS13 antibodies in patients with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1703–1710. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bettoni G, Palla R, Valsecchi C, Consonni D, Lotta LA, Trisolini SM, Mancini I, Musallam KM, Rosendaal FR, Peyvandi F. ADAMTS-13 activity and autoantibodies classes and subclasses as prognostic predictors in acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:1556–1565. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lotta LA, Valsecchi C, Pontiggia S, Mancini I, Cannavò A, Artoni A, Mikovic D, Meloni G, Peyvandi F. Measurement and prevalence of circulating ADAMTS13-specific immune complexes in autoimmune thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:329–336. doi: 10.1111/jth.12494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferrari S, Palavra K, Gruber B, Kremer Hovinga JA, Knöbl P, Caron C, Cromwell C, Aledort L, Plaimauer B, Turecek PL, et al. Persistence of circulating ADAMTS13-specific immune complexes in patients with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Haematologica. 2014;99:779–787. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.094151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mancini I, Ferrari B, Valsecchi C, Pontiggia S, Fornili M, Biganzoli E, Peyvandi F IGoT Investigators. ADAMTS13-specific circulating immune complexes as potential predictors of relapse in patients with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;39:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westwood JP, Langley K, Heelas E, Machin SJ, Scully M. Complement and cytokine response in acute Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura. Br J Haematol. 2014;164:858–866. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kosugi N, Tsurutani Y, Isonishi A, Hori Y, Matsumoto M, Fujimura Y. Influenza A infection triggers thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura by producing the anti-ADAMTS13 IgG inhibitor. Intern Med. 2010;49:689–693. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franchini M. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: Proposal of a new pathogenic mechanism involving Helicobacter pylori infection. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65:1128–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talebi T, Fernandez-Castro G, Montero AJ, Stefanovic A, Lian E. A case of severe thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura with concomitant Legionella pneumonia: Review of pathogenesis and treatment. Am J Ther. 2011;18:e180–e185. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181d1b4a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yagita M, Uemura M, Nakamura T, Kunitomi A, Matsumoto M, Fujimura Y. Development of ADAMTS13 inhibitor in a patient with hepatitis C virus-related liver cirrhosis causes thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Hepatol. 2005;42:420–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunther K, Garizio D, Nesara P. ADAMTS13 activity and the presence of acquired inhibitors in human immunodeficiency virus-related thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Transfusion. 2007;47:1710–1716. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boteju M, Weeratunga P, Sivashangar A, Chang T. Cytomegalovirus induced refractory TTP in an immunocompetent individual: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2019 May 8;19(1):394. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4037-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alhomoud M, Alhobay B. Armitage K COVID-19 infection triggering Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura IDCases. 2021:26. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dias PJ, Gopal S. Refractory thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura following influenza vaccination. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(4):444–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kojima Y, Ohashi H, Nakamura T, et al. Acute thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura after pneumococcal vaccination. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2014;25(5):512–514. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greinacher A, Selleng K, Palankar R, et al. Insights in chAdox1 nCoV-19 vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2021;138(22):2256–2268. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021013231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alislambouli M, Veras Victoria A, Matta J, Yin F. Acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura following Pfizer COVID-19 vaccination. Eur J Haematol. 2022;3(1):207–210. doi: 10.1002/jha2.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Picod A, Rebibou JM, Dossier A, et al. Immune-mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura following COVID-19 vaccination. Blood. 2022;139(16):2565–2569. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021015149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shah H, Kim A, Sukumar S, et al. sARS-CoV-2 vaccination and immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2022;139(16):2570–2573. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022015545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trisolini SM, Capria S, Artoni A, Mancini I, Biglietto M, Gentile G, Peyvandi F. Test AM Covid-19 vaccination in patients with immune-mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: a single-referral center experience. Haematol. 2023 Jul 1;108(7):1957–1959. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2022.282311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Capecchi M, De Leo P, Abbatista M, Mancini I, Agosti P, Biganzoli M, Suffrritti C, Ferrari B, Lecchi A, La Marca S, Padovan L, Scalambrino E, Clerici M, Tripodi A, Artoni A, Gualtierotti R, Peyvandi F. Risk of relapse after SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in the Milan cohort of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura patients. Haematol. 2023 Nov 1;108(11):3152–3155. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2022.282478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jang MJ, Chong SY, Kim IH, Kim JH, Jung CW, Kim JY, Park JC, Lee SM, Kim YK, Lee JE, et al. Clinical features of severe acquired ADAMTS13 deficiency in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: The Korean TTP registry experience. Int J Hematol. 2011;93:163–169. doi: 10.1007/s12185-011-0771-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benhamou Y, Boelle PY, Baudin B, Ederhy S, Gras J, Galicier L, Azoulay E, Provôt F, Maury E, Pène F, et al. Cardiac troponin-I on diagnosis predicts early death and refractoriness in acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Experience of the French Thrombotic Microangiopathies Reference Center. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:293–302. doi: 10.1111/jth.12790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vesely SK, George JN, Lämmle B, Studt JD, Alberio L, El-Harake MA, Raskob GE. ADAMTS13 activity in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome: Relation to presenting features and clinical outcomes in a prospective cohort of 142 patients. Blood. 2003;102:60–68. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bell WR, Braine HG, Ness PM, Kickler TS. Improved survival in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura-hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clinical experience in 108 patients. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:398–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108083250605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mackie I, Mancini I, Muia J, Kremer Hovinga J, Nair S, Machin S, Baker R. International Council for Standardization in Haematology (ICSH) recommendations for laboratory measurement of ADAMTS13. Int J Lab Hematol. 2020 Dec;42(6):685–696. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.13295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coppo P, Schwarzinger M, Buffet M, Wynckel A, Clabault K, Presne C, et al. Predictive features of severe acquired ADAMTS13 deficiency in idiopathic thrombotic microangiopathies: the French TMA reference center experience. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bendapudi PK, Hurwitz S, Fry A, Marques MB, Waldo SW, Li A. Derivation and external validation of the PLASMIC score for rapid assessment of adults with thrombotic microangiopathies: a cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4:157–164. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li A, Khalighi PR, Wu Q, Garcia DA. External validation of the PLASMIC score: a clinical prediction tool for thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura diagnosis and treatment. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16:164–9. doi: 10.1111/jth.13882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paydary K, Banwell E, Tong J, Chen Y, Cuker A. Diagnostic accuracy of the PLASMIC score in patients with suspected thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfusion. 2020 Sep;60(9):2047–2057. doi: 10.1111/trf.15954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Joseph A, Joly BS, Picod A, Veyradier A, Coppo P. The Specificities of Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura at Extreme Ages: A Narrative Review. J Clin Med. 2023 May;12(9):3068. doi: 10.3390/jcm12093068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zheng XL, Vesely SK, Cataland SR, Coppo P, Geldziler B, Iorio A, Matsumoto M, Mustafa RA, Pai M, Rock G, Russell L, Tarawneh R, Valdes J, Peyvandi F. ISTH guidelines for treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Oct;18(10):2496–2502. doi: 10.1111/jth.15010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rock GA, Shumak KH, Buskard NA, Blanchette VS, Kelton JG, Nair RC, Spasoff RA. Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Canadian Apheresis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:393–397. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108083250604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coppo P, Bussel A, Charrier S, Adrie C, Galicier L, Boulanger E, et al. High-dose plasma infusion versus plasma exchange as early treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003;82:27–38. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scully M, Hunt BJ, Benjamin S, Liesner R, Rose P, Peyvandi F, Cheung B, Machin SJ British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and other thrombotic microangiopathies. Br J Haematol. 2012 Aug;158(3):323–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eller Kathrin, Knoebel Paul, Bakkaloglu Sevcan A, Menne Jan J, Brinkkoetter Paul T, Grandt Leonie, Thiem Ursula, Coppo Paul, Scully Marie, Haller Maria C. European renal best practice endorsement of guidelines for diagnosis and therapy of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura published by the International Society on thrombosis and Haemostasis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37:1229–1234. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfac034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Balduini CL, Gugliotta L, Luppi M, Laurenti L, Klersy C, Pieresca C, Quintini G, Iuliano F, Re R, Spedini P, et al. High versus standard dose methylprednisolone in the acute phase of idiopathic thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: A randomized study. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:591–596. doi: 10.1007/s00277-009-0877-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Callewaert F, Roodt J, Ulrichts H, Stohr T, van Rensburg WJ, Lamprecht S, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and safety of the anti-VWF Nanobody ALX-0681 in a preclinical baboon model of acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2012;120:3603–10. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-420943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peyvandi F, Scully M, Kremer Hovinga JA, Cataland S, Knöbl P, Wu H, et al. Caplacizumab for acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic Purpura. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:511–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scully M, Cataland SR, Peyvandi F, Coppo P, Knöbl P, Kremer Hovinga JA, et al. Caplacizumab treatment for acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic Purpura. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:335–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peyvandi Flora, Cataland Spero, Scully Marie, Coppo Paul, Knoebl Paul, Johanna A. Kremer Hovinga, Ara Metjian, Javier de la Rubia, Katerina Pavenski, Jessica Minkue Mi Edou, Hilde De Winter, Filip Callewaert; Caplacizumab prevents refractoriness and mortality in acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: integrated analysis. Blood Adv. 2021;5(8):2137–2141. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Izquierdo CP, Mingot-Castellano ME, Fuentes AEK, García-Arroba Peinado J, Cid J, Jimenez MM, Valcarcel D, Gómez-Seguí I, de la Rubia J, Martin P, Goterris R, Hernández L, Tallón I, Varea S, Fernández M, García-Muñoz N, Vara M, Zarzoso MF, García-Candel F, Paciello ML, García-García I, Zalba S, Campuzano V, Gala JM, Estévez JV, Jiménez GM, López Lorenzo JL, Arias EG, Freiría C, Solé M, Ávila Idrovo LF, Hernández Castellet JC, Cruz N, Lavilla E, Pérez-Montaña A, Atucha JA, Moreno Beltrán ME, Moreno Macías JR, Salinas R, Del Rio-Garma J. Real-world effectiveness of caplacizumab vs the standard of care in immune thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood Adv. 2022 Dec 27;6(24):6219–6227. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2022008028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Albanell-Fernández M, Monge-Escartín I, Carcelero-San Martín E, Riu Viladoms G, Ruiz-Boy S, Lozano M, Soy D, Moreno-Castaño AB, Diaz-Ricart M, Cid J. Real-world data of the use and experience of caplacizumab for the treatment of acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: Case series. Transfus Apher Sci. 2023 Jun;62(3):103722. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2023.103722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sarode R. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in caplacizumab era - An individualized approach. Transfus Apher Sci. 2023 Apr;62(2):103682. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2023.103682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dutt T, Shaw RJ, Stubbs M, Yong J, Bailiff B, Cranfield T, Crowley MP, Desborough M, Eyre TA, Gooding R, Graiger J, Hanley J, Haughton J, Hermans J, Hill Q, Humphrey L, Lowe G, Lyall H, Mohsin M, Nicolson PLR, Pridde N, Rampotas A, Rayment R, Rhodes S, Taylor A, Thomas W, Tomkins O, Van Veen JJ, Lane S, Toh CH, Scully M. Real-world experience with caplacizumab in the management of acute. TTP Blood. 2021 Apr 1;137(13):1731–1740. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007599. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Coppo P, Bubenheim M, Azoulay E, Galicier L, Malot S, Big’e N, et al. A regimen with caplacizumab, immunosuppression, and plasma exchange prevents unfavorable outcomes in immune-mediated TTP. Blood. 2021;137:733–42. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Riva Silvia, Mancini Ilaria, Maino Alberto, Ferrari Barbara, Artoni Andrea, Agosti Pasquale, Peyvandi Flora. Long-term neuropsychological sequelae, emotional wellbeing and quality of life in patients with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Heamatologica 2020 Jul. 105(7):1957–1962. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.226423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bowyer A, Brown P, Hopkins B, Scully M, Shepherd F, Lowe A, Mensah P, Maclean R, Kitchen S, van Veen JJ. Von Willebrand factor assays in patients with acquired immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia purpura treated with caplacizumab. Br J Haematol. 2022 May;197(3):349–358. doi: 10.1111/bjh.18080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mazepa MA, Masias C, Chaturvedi S. How targeted therapy disrupts the treatment paradigm for acquired TTP: the risks, benefits, and unknowns. Blood. 2019 Aug 1;134(5):415–420. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Völker LA, Kaufeld J, Miesbach W, Brähler S, Reinhardt M, Kühne L, Mühlfeld A, Schreiber A, Gaedeke J, Tölle M, Jabs WJ, Özcan F, Markau S, Girndt M, Bauer F, Westhoff TH, Felten H, Hausberg M, Brand M, Gerth J, Bieringer M, Bommer M, Zschiedrich S, Schneider J, Elitok S, Gawlik A, Gäckler A, Kribben A, Schwenger V, Schoenermarck U, Roeder M, Radermacher J, Bramstedt J, Morgner A, Herbst R, Harth A, Potthoff SA, von Auer C, Wendt R, Christ H, Brinkkoetter PT, Menne J. ADAMTS13 and VWF activities guide individualized caplacizumab treatment in patients with aTTP. Blood Adv. 2020 Jul 14;4(13):3093–3101. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cuker A, Cataland SR, Coppo P, de la Rubia J, Friedman KD, George JN, Knoebl PN, Kremer Hovinga JA, Lämmle B, Matsumoto M, Pavenski K, Peyvandi F, Sakai K, Sarode R, Thomas MR, Tomiyama Y, Veyradier A, Westwood JP, Scully M. Redefining outcomes in immune TTP: an international working group consensus report. Blood. 2021 Apr 8;137(14):1855–1861. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020009150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Swisher KK, Terrell DR, Vesely SK, Kremer Hovinga JA, Lämmle B, George JN. Clinical outcomes after platelet transfusions in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Transfusion. 2009 May;49(5):873–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.02082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McDonald V, Manns K, Mackie IJ, Machin SJ, Scully MA. Rituximab pharmacokinetics during the management of acute idiopathic thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Thromb Haemost. 2010 Jun;8(6):1201–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kremer Hovinga JA, Coppo P, Lämmle B, Moake JL, Miyata T, Vanhoorelbeke K. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017 Apr 6;3:17020. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scully M, McDonald V, Cavenagh J, Hunt BJ, Longair I, Cohen H, Machin SJ. A phase 2 study of the safety and efficacy of Rituximab with plasma exchange in acute acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2011 Aug 18;118(7):1746–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Owattanapanich W, Wongprasert C, Rotchanapanya W, Owattanapanich N, Ruchutrakool T. Comparison of the long-term remission of Rituximab and conventional treatment for acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic Purpura: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2019:25. doi: 10.1177/1076029618825309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Aksoy S, Harputluoglu H, Kilickap S, Dede DS, Dizdar O, Altundag K, Barista I. Rituximab-related viral infections in lymphoma patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007 Jul;48(7):1307–12. doi: 10.1080/10428190701411441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Laganà A. Trisolini SM, Capria S True vs. false immune-mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura exacerbations: a clinical case in the caplacizumab era. Blood Coagulation and Fibrinol. 2024 Jan;35(1):37–42. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000001266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Allison AC, Eugui EM. Mycophenolate mofetil and its mechanisms of action. Immunopharmacology. 2000 May;47(2–3):85–118. doi: 10.1016/S0162-3109(00)00188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moake JL, Rudy CK, Troll JH, Schafer AI, Weinstein MJ, Colannino NM, Hong SL. Therapy of chronic relapsing thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura with prednisone and azathioprine. Am J Hematol. 1985 Sep;20(1):73–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nosari A, Redaelli R, Caimi TM, Mostarda G, Morra E. Cyclosporine therapy in refractory/relapsed patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:313–4. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cataland SR, Jin M, Lin S, Kraut EH, George JN, Wu HM. Effect of prophylactic cyclosporine therapy on ADAMTS13 biomarkers in patients with idiopathic thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol. 2008 Dec;83(12):911–5. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zappasodi P, Corso A, Castagnola C, Tajana M, Lunghi M, Bernasconi C. A successful combination of plasma exchange and intravenous cyclophosphamide in a patient with a refractory thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Eur J Haematol. 1999 Oct;63(4):278–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1999.tb01893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ahmadpoor P, Aglae C, Garo F, Cariou S, Renaud S, Reboul P, Moranne O. Humanized anti CD-20 as an alternative in chronic management of relapsing thrombotic thrombocytopenic microangiopathy resistant to Rituximab due to anti chimeric antibody. Int J Hematol. 2021 Mar;113(3):456–460. doi: 10.1007/s12185-020-03020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Doyle AJ, Stubbs MJ, Lester W, Thomas W, Westwood JP, Thomas M, Percy C, Prasannan N, Scully M. The use of obinutuzumab and ofatumumab in the treatment of immune thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Br J Hematol. 2022 Jul;198(2):391–396. doi: 10.1111/bjh.18192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shortt J, Oh DH, Opat SS. ADAMTS13 antibody depletion by bortezomib in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 3;368(1):90–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1213206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Van den Berg J, Kremer Hovinga JA, Pfleger C, Hegemann I, Stehle G, Holbro A, Studt JD. Daratumumab for immune thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood Adv. 2022 Feb 8;6(3):993–997. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tse B, Lim G, Sholzberg M, Pavenski K. Describing the point prevalence and characteristics of venous thromboembolism in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 Nov;18(11):2870–2877. doi: 10.1111/jth.15027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dutt T, Shaw RJ, Stubbs M, Yong J, Bailiff B, Cranfield T, Crowley MP, Desborough M, Eyre TA, Gooding R, Grainger J, Hanley J, Haughton J, Hermans J, Hill Q, Humphrey L, Lowe G, Lyall H, Mohsin M, Nicolson PLR, Priddee N, Rampotas A, Rayment R, Rhodes S, Taylor A, Thomas W, Tomkins O, Van Veen JJ, Lane S, Toh CH, Scully M. Real-world experience with caplacizumab in the management of acute TTP. Blood. 2021 Apr 1;137(13):1731–1740. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020007599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Elverdi Tuğrul, Çerme Melis Dila Özer, Aydın Tahacan, Eşkazan Ahmet Emre. Do patients with immune-mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura receiving caplacizumab need antithrombotic therapy? Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. 14(10):1183–1188. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2021.1944102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Selvakumar S, Liu A, Chaturvedi S. Immune thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: Spotlight on long-term outcomes and survivorship. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023 Feb 28;10:1137019. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1137019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Peyvandi F, Lavoretano S, Palla R, Feys HB, Vanhoorelbeke K, Battaglioli T, Valsecchi C, Canciani MT, Fabris F, Zver S, Réti M, Mikovic D, Karimi M, Giuffrida G, Laurenti L, Mannucci PM. ADAMTS13 and anti-ADAMTS13 antibodies as markers for recurrence of acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura during remission. Haematologica. 2008 Feb;93(2):232–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cuker A. Adjuvant rituximab to prevent TTP relapse. Blood. 2016 Jun 16;127(24):2952–3. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-04-710475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Westwood JP, Thomas M, Alwan F, McDonald V, Benjamin S, Lester WA, Lowe GC, Dutt T, Hill QA, Scully M. Rituximab prophylaxis to prevent thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura relapse: outcome and evaluation of dosing regimens. Blood Adv. 2017 Jun 26;1(15):1159–1166. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017008268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zheng XL, Vesely SK, Cataland SR, Coppo P, Geldziler B, Iorio A, Matsumoto M, Mustafa RA, Pai M, Rock G, et al. Good practice statements (GPS) for the clinical care of patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Thromb Heemost. 2020 Oct;18(10):2503–12. doi: 10.1111/jth.15009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Page EE, Kremer Hovinga JA, Terrell DR, Vesely SK, George JN. Rituximab reduces risk for relapse in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2016 Jun 16;127(24):3092–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-703827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jestin M, Benhamou Y, Schelpe AS, Roose E, Provôt F, Galicier L, Hié M, Presne C, Poullin P, Wynckel A, Saheb S, Deligny C, Servais A, Girault S, Delmas Y, Kanouni T, Lautrette A, Chauveau D, Mousson C, Perez P, Halimi JM, Charvet-Rumpler A, Hamidou M, Cathébras P, Vanhoorelbeke K, Veyradier A, Coppo P French Thrombotic Microangiopathies Reference Center. Preemptive Rituximab prevents long-term relapses in immune-mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2018 Nov 15;132(20):2143–2153. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-04-840090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Upreti H, Kasmani J, Dane K, Braunstein EM, Streiff MB, Shanbhag S, Moliterno AR, Sperati CJ, Gottesman RF, Brodsky RA, Kickler TS, Chaturvedi S. Reduced ADAMTS13 activity during TTP remission is associated with stroke in TTP survivors. Blood. 2019 Sep 26;134(13):1037–1045. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019001056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Roose E, Schelpe AS, Tellier E, Sinkovits G, Joly BS, Dekimpe C, Kaplanski G, Le Besnerais M, Mancini I, Falter T, Von Auer C, Feys HB, Reti M, Rossmann H, Vandenbulcke A, Pareyn I, Voorberg J, Greinacher A, Benhamou Y, Deckmyn H, Fijnheer R, Prohászka Z, Peyvandi F, Lämmle B, Coppo P, De Meyer SF, Veyradier A, Vanhoorelbeke K. Open ADAMTS13, induced by antibodies, is a biomarker for subclinical immune-mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2020 Jul 16;136(3):353–361. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Scully M, Knöbl P, Kentouche K, Rice L, Windyga J, Schneppenheim R, Kremer Hovinga JA, Kajiwara M, Fujimura Y, Maggiore C, Doralt J, Hibbard C, Martell L, Ewenstein B. Recombinant ADAMTS-13: first-in-human pharmacokinetics and safety in congenital thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2017 Nov 9;130(19):2055–2063. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-06-788026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]