Abstract

The United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) targets aim to reduce new HIV infections below 370 000 annually by 2025. However, there were 1.3 million new HIV infections worldwide in 2022. We collected and analyzed data for key variables of the HIV epidemic from UNAIDS and supplemented by PUBMED/EMBASE searches and national reports. A total of 53% of the HIV infections worldwide were in 14 high-prevalence countries in Southern/East Africa—where most of the funding for treatment and prevention is allocated—versus 47% in 54 low-prevalence countries. In 2022, there were more new HIV infections (770 000 vs 468 000), more HIV-related deaths (383 000 vs 225 000), higher rates of mother-to-child transmissions (16% vs 9%) and lower antiretroviral therapy coverage (67% vs 83%) in low-prevalence countries versus high-prevalence countries. To achieve UNAIDS annual new infections target for 2025, ART coverage needs to be optimized worldwide, and preexposure prophylaxis coverage expanded to 74 million people, versus 2.5 million currently treated.

Keywords: ART, epidemic, HIV, incidence, prevalence

Most of the funding for treatment and prevention of HIV is allocated to countries in Southern/Eastern Africa with the highest prevalence, but low incidence. Expansion of resources to countries with low prevalence is vital to achieving United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS targets for 2025.

BACKGROUND

The United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 95-95-95 targets for HIV delineate the objective of diagnosing 95% of people with HIV (PWH), ensuring that 95% of people diagnosed receive antiretroviral therapy (ART), and achieving viral suppression in 95% of people treated by the year 2025. In June 2021, UNAIDS key prevention goals were updated, aiming for <370 000 new infections worldwide by 2025. To reach this goal, UNAIDS advocates for the implementation of treatment as prevention and preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), targeting adolescents and risk groups.

Treatment as prevention has proven effective in reducing incidence, demonstrated by notable progress across South-Eastern African nations targeted for their high prevalence. Through an intensive internationally-funded response and ART coverage >90%, Eswatini, Botswana, Lesotho, Zimbabwe, and Malawi have some of the lowest infection rates in the world, all below 2% [1]. The availability of generic antiretrovirals has made this possible. Current first-line ART, combination tenofovir-lamivudine-dolutegravir (TLD), can now be purchased generically for approximately 40–60 USD per person per year (PPPY), but only for countries included in voluntary licensing agreements. The voluntary license for dolutegravir has unclear rationale for national access, including all low- and middle-income countries by arbitrary cutoff of gross domestic product (GDP), rather than those deemed unable to afford patented medications on top of delivery expenses or appropriate socioeconomic analysis [2]. Despite the existence of affordable and effective drugs, there were 1.3 million new HIV infections worldwide in 2022, and the rate of incidence reduction has been far below that needed to meet 2025 targets [1]. To improve progress toward 95-95-95, decisions around ART licensing and health system funding need to be equitably needs driven, rather than precedent based.

Successful treatment programmes are only possible with strong funding for sexual health services to be free at the point of care so that vulnerable people can be reached and retained by clinics. Otherwise, people will often only return to clinic when they become unwell, meaning they remain virologically unsuppressed and therefore possibly infectious. Socioeconomic factors play a huge role in the likelihood of virologic suppression: poverty (often involving an inability to get to the clinic), food insecurity, drug and alcohol problems, poor mental health, and childcare issues. PWH rely on interpersonal support such as counselling to navigate treatment. The extra costs of meaningful social support programmes to ensure high suppression rates emphasize the importance of nonexclusive antiretroviral licensing, especially for middle-income countries where drugs have little impact on incidence until they can be accessed through the Indian generics market [3]. This has resulted in Colombia challenging ViiV's exclusive licensing of dolutegravir [4].

Although efforts toward the 95-95-95 goals have potential to be successful in many high-income or high-prevalence nations with large, targeted test-and-treat or PrEP campaigns, many nations will not achieve these goals on the current trajectory. The global HIV epidemic may endure at its current size because of limited capacity for effective programs in countries excluded from access agreements or ineligible for significant external support. It is important to understand the global distribution of new HIV infections, and how to mobilize truly efficacious prevention campaigns. This paper will show which areas have the greatest contribution to global incidence and mortality of HIV to explore the implications in terms of how access efforts and international funding can be more equitably directed. To contextualize the manageable scale of the efforts needed to move toward 95-95-95 if the correct priorities are set, we will also calculate global revenues of the main HIV pharmaceutical companies.

METHODS

The UNAIDSinfo database provides estimates for a wide variety of epidemiological data, including HIV prevalence, epidemic size, ART coverage, PrEP coverage, numbers of new HIV infections, and HIV/AIDS-related deaths, as well as mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) [1]. We gathered UNAIDS data from 2023. Where UNAIDS data were not available, data were collected from national databases and reports found in specific PubMed searches, referenced in Appendix 1. Certain metrics like PrEP coverage were more poorly reported than metrics such as incidence or prevalence—where relevant, data scarcity was reported alongside results.

Countries included in this study had an epidemic size of more than 40 000 PWH, as reporting was worse for nations with smaller epidemics and prevention campaigns were not anticipated to be fully augmented. They were categorized as higher (≥3.5%) or lower (<3.5%) prevalence countries (HPCs and LPCs). This threshold split the global population of PWH roughly in half to assess weighting of disease and response between the 2 groups, with the higher prevalence group accounting for 53% and the lower prevalence group accounting for 47%.

Data were analyzed for ART coverage, PrEP uptake, new infections, mortality rate, and MTCT by generating summary statistics for HIV metrics. Mortality rate was calculated from deaths divided by epidemic size. Epidemic growth rate was calculated by new infections divided by epidemic size. This was chosen over number of new infections because it provides a ratio of transmissibility. Bubble plots were generated on Excel and were weighted by epidemic size to describe the relationship between HPCs and LPCs for each HIV metric. Quadratic trends were generated using Excel to demonstrate the relationship between HPCs and LPCs on the bubble graphs. Maps were generated through uploading the database to DataWrapper.

Number needed to treat with oral PrEP to prevent 1 infection was found to be 60 people in previous work [2]. This figure was used assess the necessary scale of PrEP coverage to reach incidence goals.

Annual revenue data for GSK, Gilead Pharmaceuticals, and Johnson & Johnson were collated from the quarterly financial reports [5–7].

RESULTS

Prevalence

Overall, there were 37 million PWH in the 68 countries included in this study. There were 19.5 million PWH across 14 HPCs, comprising 53% of the global population. All 14 HPCs were in South-Eastern Africa (Figure 1). Fifty-four LPCs were spread across the remainder of the globe (Figure 1), comprising 17.5 million infections, 47% of total HIV infections worldwide. Table 1 illustrates the key differences between the HPCs and LPCs in this study.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of HIV by country. High-prevalence countries (HPCs) (≥3.5%) vs low prevalence countries (LPCs) (<3.5%).

Table 1.

Key Epidemiological Statistics for HPCs vs LPCs in 2023

| Higher Prevalence >3.5% (n = 14) | Lower Prevalence <3.5% (n = 54) | Ratio Higher:lower | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemic size (n) | 19 462 000 | 17 459 263 | |

| ART coverage | 81.6% | 67.4% | 1.21 |

| Mortality | 225 100 | 383 190 | 0.59 |

| New infections | 468 400 | 770 703 | 0.61 |

| Annual epidemic growth | 2.41% | 4.41% | 0.55 |

| PrEP initiations | 1 323 493 (n = 12) | 1 174 539 (n = 42) | 1.13 |

| MTCT | 9% | 16% (n = 43) | 0.56 |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; MTCT, mother-to-child-transmission; PrEP, preexposure prophylaxis.

Epidemic Growth

Overall, there were 1 238 000 new infections across the countries included in this study in 2022 (Table 1). Despite a smaller total epidemic size, there were more new HIV infections in LPCs than in HPCs (770 000 vs 468 000) (Table 1), whereas the number of new infections in upper-middle or high-income countries was 375 917. The rate of HIV epidemic growth (new infections/epidemic size) was 4.4% in LPCs versus 2.6% in HPCs, showing greater relative rise in HIV infections across LPCs as well as a higher total number of new cases (Table 1).

Figure 2 shows epidemic growth rate across the globe. Most of the nations with an epidemic growth rate >5.2% were in Central and South America, Central Africa, and Central and East Asia. The majority of HPCs were in the lower 2 quartiles (10 countries), suggesting successful implementation of prevention strategies. The HPCs in higher growth rate quartiles, such as Congo and Mozambique, are outliers because of political circumstances and so do not break this association.

Figure 2.

Epidemic growth rate by country by quartile. Epidemic growth rate is the number of new infections divided by epidemic size in 2022.

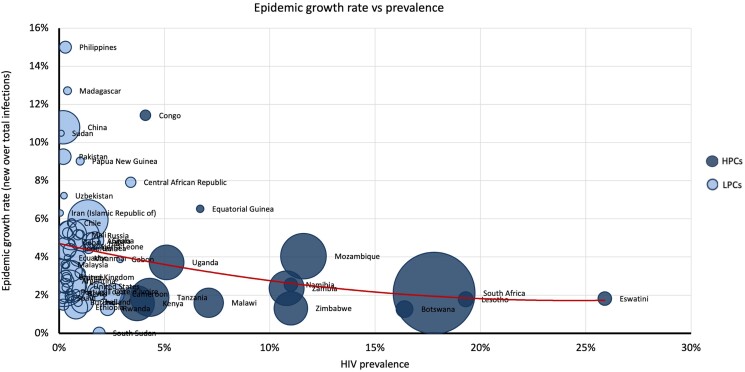

Figure 3 details the numbers behind this map in a bubble plot to give weighting by epidemic size. LPCs (light blue) with higher growth rates tended to have smaller prevalence, whereas HPCs (dark blue) generally conform to the x-axis indicating consistently low epidemic growth rate. The opposite is true for LPCs (light blue), which conform to the y-axis indicating consistently low prevalence but a wider spread of growth rates. Linear trend (red line) shows that LPCs tended to have higher epidemic growth rates. These nations tended to have a small epidemic size, apart from China, and prevalence of less than 1%.

Figure 3.

Epidemic growth rate (y-axis) versus prevalence (x-axis), weighted by epidemic size.

ART Coverage and PrEP

Globally, the rate of ART coverage for PWH was 76%. In 2022, there was lower ART coverage on average in LPCs (67%) when compared to HPCs (83%). Figure 4, which differentiates nations at >90% ART coverage (10 countries), 70%–90% ART coverage (32 countries), 50%–70% ART coverage (15 countries), and <50% ART coverage (11 countries) shows that this split again defined HPCs in South-Eastern Africa as near global exceptions (green) above 90% coverage. Ten of 14 (71%) of the HPCs highlighted here were in the lower 2 quartiles for epidemic growth rate (green and yellow in figure 2). Conversely, the only LPCs achieving >90% ART coverage were France, the United Kingdom, and Rwanda. Those with poor ART coverage were predominantly Central African and Central and East Asian countries. Notably, the United States, Russia, and India also had low rates of coverage.

Figure 4.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) coverage by country.

Figure 5 shows ART coverage against prevalence. HPCs (dark blue) conform to the upper x-axis, showing consistently high levels of ART coverage. The inverse is true for LPCs (light blue), which conform to the y-axis, indicating varying degrees of ART coverage.

Figure 5.

Percentage of people With HIV (PWH) receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART) (y-axis) versus prevalence (x-axis).

PrEP was reportedly used by 1.3 million in HPCs versus 1.2 million in LPCs, though data coverage was poor. There were 770 000 new HIV infections in LPCs in 2022 and 468 000 in HPCs. Therefore, 46 million people in LPCs would have to be treated with oral PrEP to reduce incidence to 0, and a further 28 million would need to be treated in HPCs, totalling 74 million people worldwide based on number needed to treat of 60 to prevent 1 infection.

MTCT

In concurrence with higher epidemic growth rates, LPCs had higher rates of MTCT when compared to HPCs (16% vs 9%). Figure 6 shows MTCT against prevalence. The HPCs (dark blue) conform to the x-axis showing increasing prevalence levels but consistently low MCTC rates. The LPCs (light blue) conform to the y-axis, showing consistently low prevalence but increasing rates of MTCT. The linear trend (red line) shows that countries with lower prevalence tended to have higher MTCTs.

Figure 6.

Mother-to-child-transmission (MTCT) (y-axis) versus prevalence (x-axis), weighted by epidemic size.

Case Study: Botswana

Botswana is one of the global leaders in ART delivery, with 94% coverage. As a result, the HIV epidemic growth in Botswana was well below the global average (1.3% vs 3.3%), as were AIDS-related deaths (1.1% vs 1.6%), MTCT (2% vs 11%), and AIDS-related deaths in children (0–14 years) (2.9% vs 5.6%) (Table 2). Extrapolating Botswana's 1.3% epidemic growth rate to the LPCs in this study, 550 000 new HIV infections could be prevented every year. With Botswana's 94% ART coverage globally, there would be 800 000 new infections prevented, 200 000 AIDS-related deaths prevented, 40 000 AIDS-related deaths in children aged 0–14 years, and an MTCT of 2% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Global Epidemic Key Statistics vs Botswana, and Extrapolated Cases

| Global Number 2022 | Global Rate 2022 | Botswana Rate 2022 | Total Difference in Global Number Using Botswana Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ART coverage | 29 800 000 | 76% | 94% | +6 994 664 |

| New infections | 1 300 000 | 3.3% | 1.3% | −806 764 |

| AIDS-related deaths | 630 000 | 1.6% | 1.1% | −194 117 |

| AIDS-related deaths in children (0–14 y) | 84 000 | 5.6% | 2.9% | −41 142 |

| MTCT | N/A | 11% | 2% | N/A |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; MTCT, mother-to-child-transmission; N/A, not available.

Pharmaceutical Revenue

Figure 7 shows the annual combined revenue from HIV drugs for 3 of the main HIV drug providers. In 2022, these 3 companies generated $27 billion in annual revenue from drugs used to treat HIV. The Clinton Health Access Initiative reported a benchmark price of $42 PPPY for TLD [8]. If there were global access to ART at this price, it would cost $1.6 billion per year to treat 39 million PWH. This cost is more than 16 times smaller than the HIV-related revenue generated by 3 pharmaceutical companies in 2022.

Figure 7.

Combined annual revenue of HIV drug sales.

DISCUSSION

Worldwide, 770 703 (62%) new HIV infections are now reported in 54 countries outside of South-Eastern Africa, despite their lower total epidemic size (17 459 263) than the 14 African nations (19 462 000), meaning a higher epidemic growth rate of 4.4% versus 2.6% (Table 1). Infection rate in these LPCs may be explained by lower ART coverage than HPCs in South-Eastern Africa (67% vs 83%) and lower uptake of PrEP (1.2 million vs 1.3 million), leading to significantly more HIV-related deaths (383 000 vs 225 000) and higher rates of MTCT (16% vs 9%) (Table 1). Our results highlight an increasing need for effective preventative and treatment programs in LPCs.

There were several limitations to this study. The AIDSinfo database, from most of the data were extracted, uses the SPECTRUM model. Given the limited availability of surveillance data, SPECTRUM applies modelling approaches; over- and underestimations cannot be excluded [9]. Furthermore, where AIDSinfo data were not available, we analyzed heterogeneous national reports or peer-reviewed studies, meaning potential for differing methodology and inconsistent errors. As an illustrative paper, deeper statistical analyses were not required, but a regression analysis based on GDP or health system expenditure would be beneficial to explore why these differences have arisen and where funding may be being misdirected. Last, our results must be interpreted with caution; we are not recommending deprioritizing HPCs, but upscaling responses in neglected, middle-income LPCs.

Key strategies that have reduced infection rates and mortality in South-Eastern African HPCs were developed through community, academic, and activist means. Massive community care adjustments and targeted support through aid initiatives like PEPFAR made an exceptional difference. However, these efforts only became truly transformative when aligned with cheap and readily available ART. For this to happen, patient and civil society groups put prolonged pressure on the pharmaceutical industry. Since then, safety and efficacy of pharmaceutical prevention and treatment for HIV has steadily improved. Novel drugs are no longer needed. But research and design processes for new drugs are still used to justify rising pharmaceutical revenues: $27 billion across the main 3 for HIV technologies in 2023. Regardless, most genuinely innovative research is public [10]. Despite this, the results are exclusively licensed and commercialized, and access initiatives are limited to discretionary voluntary licensing agreements.

Previous analysis has shown that these access agreements are not justified by GDP or health system funding [2, 5]. Our current analysis shows that they are not justified by HIV infection trends, mortality distribution, or strength of treatment and prevention programs either. These agreements need to be more empirically validated and adaptive, without sharp cutoffs delineated by simple metrics such as prevalence. Many MICs in South America, West Africa, and Asia miss out on access initiatives despite high infection rates because they are below prevalence cutoffs and above GDP cutoffs set in these agreements.

Technology patenting and the resultant legislative challenges for access to medicines misdirect energy and funding from the real causes of prolonged and unequal HIV epidemics. Health equity means uninhibited health care according to need. Risk groups are often also discriminated against by existing services. The huge caseload and mortality in MICs results from avoidable and reducible health inequity. Generically available medicines are essential, and the pathway for their use must also be safe, efficient, and destigmatized. To push toward 95-95-95, LPCs can apply lessons learnt from successful campaigning and clinical activity in South-East African nations. Though vertical HIV-targeted programs can detract from wider shifts in health system strengthening [6], some mechanisms of successful HIV programs have had widespread positive influence on health outcomes that could translate to other nations, even those with stable health care systems, for example, health system decentralization to communities [7], task shifting [11], and uptake of mobile technology [12]. Transferable methods will be presented chronologically: prevention, testing, treatment, retention-in-care.

Prevention must be cheap and readily available. Total use of PrEP is far below the 74 million people required to optimize preventive efficacy. More PrEP has been delivered in 14 South-East African countries than 54 LPCs around the rest of the world. Huge incidence reduction in the Netherlands (95%) and Australia (88%) show what is possible with rapid and wide introduction of PrEP [13, 14]. Crucially, these programs provide PrEP free at the point of access. Clinical trials and incidence surveys have shown that Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (TDF)/Emtricitabine (FTC) needs to be given to at least 60 people at high risk of HIV transmission to prevent 1 new infection, so free or extremely cheap access is vital.

Oral PrEP (TDF/FTC) is off-patent and available across the globe. However, roll out of PrEP has been poor, despite the Global Fund pooled procurement price of approximately 45 USD per year [8]. One year's access to generic PrEP at the appropriate scale to meet global prevention targets would cost approximately $37 million, less than one-hundredth the annual revenues of the main 3 pharmaceutical companies. Meanwhile, cabotegravir (CAB-LA) has been licensed as a long-acting injectable form of PrEP but is inaccessible for many low- and middle-income countries [8]. CAB-LA provides a different option, potentially more acceptable and less stigmatizing with a 2-monthly, pill-free regimen. Efficacy in clinical trial settings is superior to TDF/FTC [15, 16]. However, ViiV markets CAB-LA at a nonprofit price of $25 per shot, or $150 per year, versus $45 per year for generic oral PrEP [8]. Though a voluntary license for access in LMICs was reached, 38 countries were excluded from the license despite constituting 122 000 infections and lower GDP than included nations, meaning prices up to $22 200 per year [2]. Furthermore, the restrictive ViiV Medicines Patent Pool (MPP) licensing agreement means that supply is limited to a few points of production, which are saturated until 2028, meaning no access for LMICs.

Prevention is not always possible. Test-and-treat within 24 hours is the next best option, recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). Community-based clinics and task-shifting have made this possible in South-East Africa. However, these changes are meaningless without destigmatization of HIV infection, and improved rights for gay communities and sex workers [17]. Point-of-care testing still only constitutes 30% of HIV testing [8, 18]. Low-cost, community-based testing kits are more accessible and less stigmatizing [8, 18]. These should be offered at negligible cost to at-risk communities, alongside education, especially through active recall of people known to services, for example accompanying needle-exchange programs for intravenous drug users [19]. Prices continue to fall, with many companies now offering combined home testing, though not yet approved by the WHO. MICs should focus on local production capacity or collaborative pooled procurement mechanisms like the WHO MPP to acquire high quantities of tests at low cost [20]. However, MPP usage has been limited; barriers to its use must be assessed and broken down, as seen with dolutegravir.

Countries not included in licensing deals for dolutegravir had to pay a median 8718 USD PPPY in 2018 because it is still on patent until July 2029 [21, 22]. Colombia, for example, has been forced to attempt a compulsory licence for dolutegravir [4]. Global access to generic TLD would cost $1.6 billion, 16 times less than the $27 billion revenues of the main 3 pharmaceutical companies [23–25]. Corporate responsibility to the public should be enforceable, with the expansion of march-in agreements equivalent to Bayh-Dole, allowing intervention at early stages of production and distribution.

Possibly, as debate ensues about the future of funds like PEPFAR, which supports vertical HIV programs in South-East Africa with 76% of its funding [26], ways in which international aid organizations could transform to enact deeper change rather than reciprocating outdated power dynamics should be considered. For example, PEPFAR could be composted to nurture ground-level organizations or more impactful and representative civil society groups. Restrictive licensing regimes and pharmaceutical lobbying within congress and around Trade Agreements must be challenged. At the very least, support must be negotiated for MICs no longer covered by the Global Fund or voluntary license agreements.

CONCLUSION

LPCs now constitute more than half of the global burden of new HIV infections, mortality, and MTCT. To bring global new infections below the UNAIDS target of 370 000 per year by 2025, ART coverage needs to be optimized worldwide, and PrEP coverage expanded to 74 million people versus 2.5 million currently treated. This is possible with cheap generic TLD and TDF/FTC, for a fraction of the current global expenditure on pharmaceuticals for HIV. To meet UNAIDS 95-95-95 goals, stigma and inequality must be targeted, if the necessary funding space is to be opened up for MICs to suitably strengthen health systems and provide equitable HIV prevention and care, multilateral regulation must be reshaped so that the price of health technologies is not a barrier to progress in any nation.

Appendix 1.

Data collected for 14 high-prevalence countries (>3.5%) and 54 low-prevalence countries (<3.5%) with >40 000 people living with HIV

| Country | Epidemic Size | Prevalence (%) | Percentage on ART | Incidence 2022 | Epidemic Growth Rate | MTCT | AIDS-related Deaths | Income Band | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-prevalence Countries (>3.5%) | |||||||||

| Eswatini | 220 000 | 25.90% | 96.1% | 4000 | 1.8% | 2% | 2700 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Lesotho | 270 000 | 19.30% | 87.2% | 4800 | 1.8% | 6% | 4000 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| South Africa | 7 600 000 | 17.80% | 75.0% | 160 000 | 2.1% | 3% | 45 000 | Upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| Botswana | 340 000 | 16.40% | 94.3% | 4300 | 1.3% | 2% | 3800 | Upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| Mozambique | 2 400 000 | 11.60% | 81.8% | 97 000 | 4.0% | 10% | 48 000 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Namibia | 220 000 | 11.00% | 89.6% | 5600 | 2.5% | 4% | 3100 | Upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| Zimbabwe | 1 300 000 | 11.00% | 94.9% | 17 000 | 1.3% | 8% | 20 000 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Zambia | 1 400 000 | 10.80% | 90.7% | 33 000 | 2.4% | 9% | 19 000 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Malawi | 1 000 000 | 7.10% | 93.2% | 16 000 | 1.6% | 8% | 12 000 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Equatorial Guinea | 72 000 | 6.70% | 41.4% | 4700 | 6.5% | 24% | 2800 | Upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| Uganda | 1 400 000 | 5.10% | 86.5% | 52 000 | 3.7% | 7% | 17 000 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Tanzania | 1 700 000 | 4.30% | 95.1% | 32 000 | 1.9% | 7% | 22 000 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Congo | 140 000 | 4.10% | 24.3% | 16 000 | 11.4% | 32% | 7700 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Kenya | 1 400 000 | 3.70% | 92.7% | 22 000 | 1.6% | 9% | 18000 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Low-prevalence Countries (<3.5%) | |||||||||

| Central African Republic | 120 000 | 3.40% | 50.9% | 9500 | 7.9% | 26% | 4500 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Gabon | 49 000 | 2.90% | 58.3% | 1900 | 3.9% | 13% | 1800 | Upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| Cameroon | 480 000 | 2.60% | 88.5% | 9900 | 2.1% | 14% | 10 000 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Rwanda | 230 000 | 2.30% | 93.6% | 3000 | 1.3% | 5% | 2700 | Low | UNAIDS |

| South Sudan | 160 000 | 1.90% | 32.9% | 11 | 0.0% | 26% | 7600 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 410 000 | 1.80% | 71.4% | 9000 | 2.2% | 11% | 10 000 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Ghana | 350 000 | 1.70% | 63.6% | 17 000 | 4.9% | 17% | 9400 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Haiti | 140 000 | 1.70% | 78.0% | 6600 | 4.7% | 18% | 1600 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Togo | 110 000 | 1.70% | 79.0% | 2400 | 2.2% | 16% | 2400 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Angola | 310 000 | 1.50% | 46.5% | 15 000 | 4.8% | 16% | 13 000 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Guinea | 130 000 | 1.40% | 62.4% | 5800 | 4.5% | 25% | 3500 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Sierra Leone | 77 000 | 1.40% | 75.3% | 3500 | 4.5% | 16% | 2300 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Nigeria | 1 800 000 (2019) | 1.37% | 63.0% | 107 112 (2019) | 6.0% | – | 45894 (2019) | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Russia | 1 137 000 | 1.15% | 45.0% | 58 340 | 5.1% | 2.2% | 34 000 | upper-middle | HIV Russia. [Accessed from: https://tochno.st/problems/hiv] |

| Thailand | 560 000 | 1.10% | 81.6% | 9200 | 1.6% | 2% | 11 000 | upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| Chad | 120 000 | 1.00% | 73.9% | 3800 | 3.2% | 19% | 2800 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Dominican Republic | 79 000 | 1.00% | 63.1% | 4100 | 5.2% | 16% | 1500 | Upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| Papua New Guinea | 72 000 | 1.00% | 60.9% | 6500 | 9.0% | 34% | 1100 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Burundi | 80 000 | 0.90% | 85.5% | 1300 | 1.6% | 11% | 1300 | Low | CEIC Data [Accessed from: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/colombia/social-health-statistics/co-antiretroviral-therapy-coverage--of-people-living-with-hiv] |

| Mali | 120 000 | 0.90% | 50.0% | 6200 | 5.2% | 32% | 4900 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Myanmar | 280 000 | 0.90% | 74.5% | 11 000 | 3.9% | 24% | 6400 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Benin | 72 000 | 0.80% | 81.7% | 1500 | 2.1% | 11% | 1900 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Ethiopia | 610 000 | 0.80% | 82.7% | 8300 | 1.4% | 12% | 11000 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Brazil | 990 000 | 0.60% | 73.8% | 51 000 | 5.2% | – | 13000 | Upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| Burkina Faso | 97 000 | 0.60% | 80.9% | 1900 | 2.0% | 14% | 2600 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Chile | 83 000 | 0.60% | 74.1% | 4800 | 5.8% | 14% | 566 (2019) | High | Statista |

| Cuba | 42 000 | 0.60% | 66.8% | 2000 | 4.8% | 6% | 500 | Upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 490 000 | 0.60% | 82.3% | 16 000 | 3.3% | 26% | 12 000 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Cambodia | 76 000 | 0.50% | 85.4% | 1400 | 1.8% | 10% | 1100 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Colombia | 190 000 | 0.50% | 74.0% | 8300 | 4.4% | 11% | 1500 | Upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| Portugal | 46 000 | 0.50% | 87.0% | 1000 | 2.2% | – | 500 | High | UNAIDS |

| Venezuela | 92 000 | 0.50% | 67.2% | 1800 | 2.0% | – | 1500 | Lower-middle | GNI [Accessed from: https://publications.iadb.org/en/venezuela-still-upper-middle-income-country-estimating-gni-capita-2015–2021] |

| United States | 1 200 000 | 0.47% | 55.8% | 29 500 | 2.5% | – | 18 489 (2020) | High | CDC [Accessed from: https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics] |

| Argentina | 182 041 | 0.40% | 58.2% | 5000 | 2.7% | – | 1300 | Upper-middle | Index Mundi [https://www.indexmundi.com/facts/argentina/hiv-incidence] |

| Ecuador | 48 000 | 0.40% | 79.7% | 1900 | 4.0% | 12% | 500 | Upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| Madagascar | 70 000 | 0.40% | 17.5% | 8900 | 12.7% | 39% | 3200 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Mexico | 370 000 | 0.40% | 62.0% | 20 000 | 5.4% | 22% | 4600 | Upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| Peru | 110 000 | 0.40% | 79.1% | 5800 | 5.3% | 16% | 1000 | Upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| United Kingdom | 91 432 | 0.33% | 98.4% | 2692 | 2.9% | – | 723 | High | UK GOV [Accessed from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hiv-annual-data-tables] |

| Canada | 62 790 | 0.31% | 87.0% | 1500 | 2.4% | – | 1538 | High | Government of Canada [Accessed from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/estimates-hiv-incidence-prevalence-canada-meeting-90–90–90-targets-2020.html] |

| France | 200 000 | 0.30% | 97.0% | 5900 | 3.0% | 3% | 1000 | High | UNAIDS |

| Indonesia | 540 000 | 0.30% | 33.3% | 24 000 | 4.4% | 30% | 26 000 | Upper-middle | UNAIDS |

| Malaysia | 86 000 | 0.30% | 54.7% | 3100 | 3.6% | 2% | 2500 | Upper-middle | Code Blue [Accessed from: https://codeblue.galencentre.org/2022/12/06/hiv-stigma-in-malaysia-still-very-much-alive-in-2022/] |

| Philippines | 160 000 | 0.30% | 42.5% | 24 000 | 15.0% | 41% | 1500 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Senegal | 42 000 | 0.30% | 79.4% | 1500 | 3.6% | 16% | 1000 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Viet Nam | 250 000 | 0.30% | 73.4% | 6200 | 2.5% | 13% | 4100 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Uzbekistan | 48 000 | 0.23% | 76.0% | 3463 | 7.2% | 680 | Lower-middle | World bank [Accessed from: https://data.worldbank.org/country/uzbekistan] | |

| India | 2 500 000 | 0.20% | 67.0% | 66 000 | 2.6% | 20% | 40 000 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

| Italy | 140 000 | 0.20% | 80.0% | 2100 | 1.5% | – | 1000 | High | UNAIDS |

| Pakistan | 270 000 | 0.20% | 12.7% | 25 000 | 9.3% | – | 12 000 | Lower-middle | WHO [Accessed from https://www.emro.who.int/asd/country-activities/pakistan.html] |

| Spain | 150 000 | 0.20% | 88.9% | 2785 | 1.9% | – | 1000 | High | UNAIDS |

| China | 1 250 000 | 0.19% | 78.3% | 135 000 | 10.8% | – | 34 800 | Upper-middle | Bavinton et al, 2021 [Accessed from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468–2667(21)00112–2/fulltext] |

| Sudan | 41 000 | 0.10% | 27.6% | 4300 | 10.5% | 39% | 100 | Low | UNAIDS |

| Iran (Islamic Republic of) | 46 000 | 0.05% | 36.2% | 2900 | 6.3% | 33% | 2300 | Lower-middle | UNAIDS |

Non-UNAIDS sources are listed in column K. Non-UNAIDS data are highlighted in red.

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; MTCT, mother-to-child transmission; UNAIDS, United Nations Program and HIV/AIDS; WHO, World Health Organization.

Contributor Information

Toby Pepperrell, School of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK.

Andrew Hill, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, NHS Scotland, Glasgow, UK.

Samuel Cross, Department of Translational Medicine, Liverpool University, Liverpool, UK.

Notes

Financial support . This work was funded by the International Treatment Preparedness Coalition (ITPC)—Make Medicines Affordable Campaign.

Patient consent statement. This paper does not include factors necessitating patient consent.

References

- 1. UNAIDS . AIDSinfo database 2022. Available at: https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/. Accessed 8 December 2023.

- 2. Pepperrell T, Cross S, Hill A. Cabotegravir—global access to long-acting pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Open Forum Infect Dis 2022; 10:ofac673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Waning B, Diedrichsen E, Moon S. A lifeline to treatment: the role of Indian generic manufacturers in supplying antiretroviral medicines to developing countries. J Int AIDS Soc 2010; 13:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kansteiner F. Colombia, pursuing healthcare savings, plots compulsory license for ViiV's HIV drug dolutegravir. Fierce Pharma. 2023. Available at: https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/seeking-cheaper-generics-colombia-plots-compulsory-license-viivs-hiv-med-dolutegravir.

- 5. Gilead . SEC Filing 2022, Gilead Sciences; 2022:60. Available at: https://s29.q4cdn.com/585078350/files/doc_financials/2022/q4/068833e5-38fe-4148-b82f-2324d040315e.pdf.

- 6. Johnson & Johnson. Annual report 2022. Johnson & Johnson; 2022:25. Available at: https://www.investor.jnj.com/files/doc_financials/2022/ar/2022-annual-report.pdf.

- 7. Kates J, Carbaugh A, Isbell M. Key issues and questions for PEPFAR's future. KFF: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2021. Available at: https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/issuebrief/key-issues-and-questions-for-pepfars-future/#:∼:text=While%20early%20actions%20by%20PEPFAR,mitigate%20impact%20and%20make%2Dup.

- 8. CHAI . HIV Market Report: the state of HIV treatment, testing, and prevention in low- and middle-income countries. Clinton Health Access Initiative. October 2023.

- 9. Mahy M, Penazzato M, Ciaranello A, et al. Improving estimates of children living with HIV from the spectrum AIDS impact model. AIDS 2017; 31 Suppl 1:S13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Galkina Cleary E, Beierlein JM, Khanuja NS, McNamee LM, Ledley FD. Contribution of NIH funding to new drug approvals 2010–2016. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018; 115:2329–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Callaghan M, Ford N, Schneider H. A systematic review of task- shifting for HIV treatment and care in Africa. Hum Resour Health 2010; 8:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Braun R, Catalani C, Wimbush J, Israelski D. Community health workers and mobile technology: a systematic review of the literature. PLoS One 2013; 8:e65772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hughson G. 95% decline in new HIV infections in Amsterdam Aidsmap; 2023. Available at: https://www.aidsmap.com/news/dec-2023/95-decline-new-hiv-infections-amsterdam#:∼:text=New%20cases%20of%20HIV%20infection,treatment%20have%20achieved%20viral%20suppression.

- 14. IAS . HIV transmission virtually eliminated in Inner Sydney, Australia 2023. Available at: https://www.iasociety.org/news-release/hiv-transmission-virtually-eliminated-inner-sydney-australia.

- 15. Delany-Moretlwe S, Hughes JP, Bock P, et al. Cabotegravir for the prevention of HIV-1 in women: results from HPTN 084, a phase 3, randomised clinical trial. Lancet 2022; 399:1779–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Landovitz RJ, Donnell D, Clement ME, et al. Cabotegravir for HIV prevention in cisgender men and transgender women. N Engl J Med 2021; 385:595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brent RJ. The value of reducing HIV stigma. Soc Sci Med 2016; 151:233–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Suthar AB, Ford N, Bachanas PJ, et al. Towards universal voluntary HIV testing and counselling: a systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based approaches. PLoS Med 2013; 10:e1001496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Desai M, Woodhall SC, Nardone A, Burns F, Mercey D, Gilson R. Active recall to increase HIV and STI testing: a systematic review. Sex Transm Infect 2015; 91:314–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. MPP . Medicines Patent Pool: About. 2023. Available at: https://medicinespatentpool.org/.

- 21. Johns BA, Aoyama Y, Hakogi T. Dolutegravir Prodrugs, Worldwide Patent Applications. 2014. Available at: https://patents.google.com/patent/SI2320908T1/en.

- 22. Sim J, Hill A. Is pricing of dolutegravir equitable? A comparative analysis of price and country income level in 52 countries. J Virus Erad 2018; 4:230–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. GSK . Annual report 2022. Glaxo-Smith-Klein; 2022:274–275. Available at: https://www.gsk.com/media/9956/annual-report-2022.pdf.

- 24. Park C, Moon S, Burrone E, et al. Voluntary licensing: an analysis of current practices and key provisions in antiretroviral voluntary licences. In: XIX AIDS Conference. Washington: Medicines Patent Pool, 2012.

- 25. Bayer R. Clinical progress and the future of HIV exceptionalism. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:1042–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. UNAIDS . Key populations. 2016. Available at: https://www.unaids.org/en/topic/key-populations#:∼:text=UNAIDS%20considers%20gay%20men%20and,lack%20adequate%20access%20to%20services.