Child health has improved greatly in the past decade, thanks to research that has quantified health problems and identified strategies for improving child health. The Working Group on Women and Child Health reviews the major advances in this field in developing countries since 1990 and argues that research is fundamental to further improvements in child health

Child mortality (before age 5 years) has shown a relative decrease of 15% since 1990 but remains above 100 per 1000 live births in more than 40 countries.1 The risk of death can be reduced through evidence based interventions such as immunisation and oral rehydration treatment. Research has helped to quantify child health problems, identified strategies to improve health, and shown the effectiveness of interventions. In preparation for the forthcoming United Nations special session on children, we review the major advances in child health in developing countries since 1990 and illustrate the role of research in this progress.

Summary points

Child health has improved markedly over the past 10 years

In many developing countries, mortality among children under 5 remains above 100 deaths per 1000 live births; most of these deaths are preventable

Reduction of childhood morbidity and mortality remains a public health priority worldwide

Investing in survival of children is an essential element of national development

Research is fundamental to further improvements in child health

Without continued and increased research investment, further advances to improve the health of the world's children are put at risk

Methods

We reviewed the literature published between January 1990 and June 2001 to document progress of and challenges in child health research since the previous UN session for children in 1990. The Medline search strategy was based on the combination (Boolean operator AND) of “child” and “developing countries” and the following keywords: breastfeeding, diarrhoeal diseases, health system, HIV infection, immunisation, injuries, malaria, measles, mental health, mortality, opportunistic diseases, oral health, perinatal health, respiratory infections, sanitation, and welfare. The search identified 4701 references, of which we selected 488 on title and 137 on content. We identified unpublished documents and reports by major child health institutions through an electronic mail survey to over 90 informants in national and international public, private, and non-profit organisations.

The magnitude of child morbidity and mortality

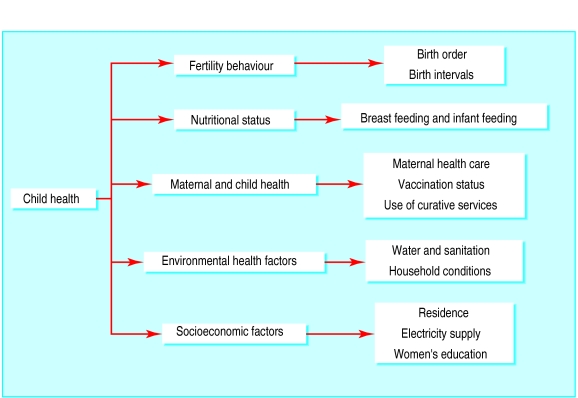

Five of the 10 most important conditions contributing to the global burden of disease are childhood diseases (table 1). Respiratory infections and diarrhoeal diseases are the most important causes of mortality in children under 5, with about eight million deaths globally each year.2 Most deaths are preventable by targeting factors such as fertility behaviour, nutritional status of children, and breastfeeding patterns (fig 1).3

Table 1.

Leading causes of disability adjusted life years (DALYs)* worldwide in 19902

| Causes

|

Rank

|

Percentage of total

|

|---|---|---|

| Lower respiratory infections† | 1 | 8.2 |

| Diarrhoeal diseases† | 2 | 7.2 |

| Perinatal conditions† | 3 | 6.7 |

| Unipolar major depression | 4 | 3.7 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 5 | 3.4 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 6 | 2.8 |

| Tuberculosis | 7 | 2.8 |

| Measles† | 8 | 2.6 |

| Road traffic crashes | 9 | 2.5 |

| Congenital abnormalities† | 10 | 2.4 |

DALYs are indicators of the time lived with a disability and the time lost to premature mortality.

Primarily or exclusively childhood diseases.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework: the determinants of child health (adapted from Rutstein3)

Research to improve child survival

Child health research aims to quantify childhood mortality and morbidity, improve understanding of causes, and identify appropriate interventions (table 2). The following three examples document the value of child health research, leading to successful interventions, translation of research findings into public health practice, and subsequent improvement in survival of children.

Table 2.

Types of research in the area of child health and nutrition

| Type of research

|

Objective

|

Examples of needs or recent advances

|

|---|---|---|

| Descriptive epidemiology and burden of disease | To describe the magnitude of the problem and identify the causes of childhood illness and death in different communities | The importance of childhood injuries and abuse is greatly under-recognised4 |

| Aetiology and mechanisms | To understand the determinants of childhood diseases | Streptococcus pneumoniae causes 50% of all early infant meningitis5 |

| Development of interventions | To design the most appropriate strategies to improve child health | Teaching mothers to provide antimalarial drugs promptly to sick children at home decreases mortality in under 5s6 |

| Impact and evaluation | To measure the effect of the implemented strategies and raise new research questions | Less than half of children in western and central Africa are receiving measles vaccine7 |

| Health systems | To increase the effectiveness of child health interventions and services | Improved quality of hospital care may lead to better outcomes in severely ill children8 |

| Policy | To analyse retrospectively and monitor prospectively the scaling up of child health and nutrition interventions | Social marketing of insecticide treated nets contributes to improving survival of children9 |

Vitamin A deficiency

Vitamin A deficiency is a major cause of childhood blindness and a contributor to mortality from measles and diarrhoea in Asia and Africa. In the early 1990s, results from observational studies showed an increased mortality among children with clinical xerophthalmia. Randomised trials subsequently showed that improving the vitamin A status of deficient children significantly reduced mortality,10–12 although not always.13 A South African study found that vitamin A supplementation in children with moderate or severe measles halved mortality.14 Large dose vitamin A treatment thus became part of the routine management of measles, to reduce the incidence of both blindness and fatality. Vitamin A supplementation may also improve outcome in HIV infected children with diarrhoea.15

International agencies have worked with governments from affected areas to train healthcare workers in distributing vitamin A and setting up food fortification programmes, linking vitamin A distribution to immunisation programmes and other child survival programmes (box B1).16 Further research should focus on ways to monitor and evaluate such programmes and extend their coverage to children who do not routinely access health services.

Box 1.

Research on vitamin A deficiency—lessons learnt

- Research findings and development of indicators to assess vitamin A status by biologists, nutritionists, clinicians, and epidemiologists with international agencies have encouraged the development of programmes to prevent vitamin A deficiency at national levels

- Research into social marketing, education, and communication strategies to encourage changes in dietary practices and delivery of health services has contributed substantially to improving the coverage of effective programmes

Mother to child transmission of HIV

Results from epidemiological studies in the late 1980s and early 1990s revealed that, worldwide, at least 30% of infants born to HIV infected mothers acquired HIV infection. In some developing countries the prevalence of HIV infection in pregnant women now approaches 30-40%, and mother to child transmission of HIV contributes substantially to child mortality.17 Such transmission can occur in utero, intrapartum, and postpartum via breast milk.18

Reducing maternal HIV viral load through antiretroviral treatment administered prophylactically before and during delivery significantly reduces the risk of transmission.19–22 Further reduction in the risk of mother to child transmission in developed countries can be achieved through delivery by elective caesarean section, combination antiretroviral treatment, and avoidance of breast feeding. In countries where randomised trials have shown simple and shorter antiretroviral prophylaxis interventions to be effective, results from observational studies are now showing the effectiveness of such interventions outside trial settings.23,24 Postnatal transmission through breast feeding remains an important problem, however, and further research is ongoing to improve the safety of breast feeding in settings with high prevalence of HIV and where refraining from breast feeding is not an option.

Thus, by 2000, governments and organisations such as the World Health Organization, Unicef, and UNAIDS could make informed policy decisions to prevent mother to child transmission of HIV.25 Currently, the focus is on the wider implementation of simplified interventions along with guidelines on breast feeding. Research should now aim to identify behavioural, social, cultural, and economic factors that may limit access to and use of these effective interventions (box B2).26

Box 2.

Research on preventing mother to child transmission of HIV—lessons learnt

- Large, sustained, and coordinated research effort with clear goals can yield high impact results

- Science has informed evidence based strategies to substantially reduce mother to child transmission, but these strategies are far from being universally applied

- Research now needs to identify ways to reach the women and children who are at greatest risk

Malaria prevention and bed nets

Malaria in children is estimated to cause one million child deaths each year in sub-Saharan Africa.2 Clarification of the role of the life cycles of parasites and mosquitos led to the hypothesis that the number of infective bites could be reduced by using protective bed nets. Indeed, the use of bed nets treated with non-toxic, synthetic pyrethroid has been shown to result in significant reduction of febrile episodes in children27 and all-cause mortality among children aged 1-4 years,28 although the methods of insecticide application have caused concern.29 Large scale effectiveness studies in the Gambia and Kenya show the impact of this form of malaria control in national programmes on child mortality23 and paediatric hospital admissions.30 The evidence base for the use of insecticide treated bed nets has recently been greatly enhanced by economic evaluations conducted alongside these trials.31

The transition of research results into a sustainable public health intervention has been hampered by cost, compliance, and public acceptance (box B3). Research is now needed to clarify the value of social marketing, the effect of affordable price scales, and requirements for behavioural change. The recently published results from a Tanzanian study taking these factors into account showed that the large scale use of bed nets remained effective for at least three years, improving child survival by 27%.32

Box 3.

Research on use of bed nets for preventing malaria—lessons learnt

- Research has led to the development of a low cost intervention against malaria

- The low number of children sleeping under insecticide treated bed nets at night calls for operational research at a family level to improve access and proper use

- Sustained availability of this intervention requires effective infrastructures and mechanisms, able to empower communities to tackle childhood malaria

Research challenges for the next decade

Evidence from child health research over the past 10 years has provided guidance to decision makers. Priority must be given to funding research that will optimise health benefits in the most appropriate and effective way (table 3).33

Table 3.

Selected research challenges for the next decade to further improve child health in developing countries

| Type of research

|

Example

|

|---|---|

| Descriptive epidemiology and burden of disease | Access to quality health care |

| Aetiology and mechanisms | Prevention of childhood injuries and abuse |

| Development of interventions | Community based care for neonatal survival |

| Impact and evaluation | Vaccination programmes; prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV |

| Health systems | Quality of childhood care |

| Policy | HIV orphans programmes |

To maximise efficiency and responsiveness of research into child health and nutrition, setting of research priorities should be based on evidence, consider local ownership and partnership, respect ethical issues, and address the interactions between child health and other sectors.2,34,35 The multiplicity of child health determinants calls for a multisectoral partnership—a combination of socioeconomic policies and health interventions. Further research to inform such policy packages is essential.

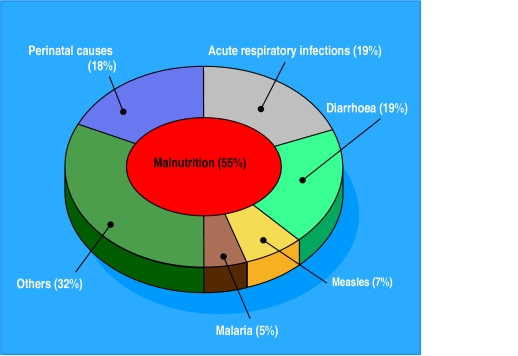

The burden of childhood morbidity and mortality could be further reduced through the reduction of gaps in research resources and capacity. Although there are limited accurate estimates of global spending and the amount allocated for research on the main diseases, an imbalance exists between the burden of disease and investment in research and development for the world's two biggest killer diseases (fig 2). Although pneumonia and diarrhoeal diseases represent 11% of the global burden of disease, and a much higher percentage in children (38%), only an estimated 0.2% of the total amount spent on research and development is allocated to these conditions.38

Figure 2.

Main causes of death in children under 5 years of age in developing countries, 1995 (adapted from Murray and Lopez36 and Pelletier et al37)

Research evaluating the effectiveness and safety of population based intervention packages would contribute to appropriate use of funds and prioritise effective interventions in child health and nutrition.39 To maximise support for initiatives in child research and the impact of available research results, each country, no matter how poor, should adopt essential national health research strategies emphasising priorities and national ownership of research findings, equity in health care, and translation of research into policy and action.35

Strengthening links between non-governmental organisations, health workers, religious leaders, women's groups, and others and integrating the health system and other sectors into a dynamic network are important for the introduction of programmes based on research findings.40 Furthermore, many results of child health research from one setting will be applicable to another—for example, vaccines to protect individual children and communities; disease eradication programmes (poliomyelitis); and effective control of communicable diseases such as tuberculosis, measles, malaria, and AIDS. Such transfer of knowledge has been successful in the 1990s but needs to be further encouraged and strengthened.

Conclusion

Research has resulted in substantial progress in child health over the past 10 years, but many problems remain to be tackled. Further progress requires that research continues to deal with the needs of children affected by preventable conditions in the developing world. Strengthening national research capacities to respond to local health needs is fundamental for the implementation and sustainability of research findings at a population level. A dynamic interaction between researchers, policy makers, advocacy groups, and funding institutions, within developing and developed nations, is essential to ensure that priorities in child research are based on sound evidence and remain at the top of the international development agenda.

Acknowledgments

We thank E Mouillet (ISPED) for assistance with the literature review. Unpublished material and reports were made available by A de Francisco (Global Forum for Health Research, Geneva) and O Fontaine (WHO, Geneva). The Global Forum for Health Research commissioned us to prepare a report on the status of child health and nutrition research (Child health research: a foundation for improving child health. Geneva: WHO, 2002. (WHO/FCH/CAH/02.3.)), which forms the basis of this review paper. We also thank the participants in the Global Forum for Health Research Workshop in Geneva, Switzerland, 18-21 April 2001, for their input in reviewing the background document used for this paper. Special thanks are due to the participants in the electronic survey.

Footnotes

Funding: Global Forum for Health Research.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World health report 1999. Geneva: WHO; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ad Hoc Committee on Health Research Relating to Future Interventions Options. Investing in health research and development. Geneva: WHO; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutstein SO. Factors associated with trends in infant and child mortality in developing countries during the 1990s. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:1256–1270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deen JL, Vos T, Huttly SR, Tulloch J. Injuries and noncommunicable diseases: emerging health problems of children in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77:518–524. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Young Infants Study Group. Bacterial etiology of serious infections in young infants in developing countries: results of a multicentre study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18(suppl):S17–S22. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199910001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kidane G, Morrow RH. Teaching mothers to provide home treatment of malaria in Tigray, Ethiopia: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:550–555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02580-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutts FT, Henao-Restrepo A, Olive JM. Measles elimination: progress and challenges. Vaccine. 1999;17:S47–S52. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00309-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nolan T, Angos P, Cunha AJ, Muhe L, Qazi S, Simoes EA, et al. Quality of hospital care for seriously ill children in less-developed countries. Lancet. 2001;357:106–110. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03542-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong Schellenberg JRM, Abdulla S, Nathan R, Mukasa R, Marchant TJ, Kibumbih N, et al. Effect of large-scale social marketing of insecticide-treated nets on child survival in rural Tanzania. Lancet. 2001;357:1241–1247. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghana VAST Study Team. Vitamin A supplementation in northern Ghana: effects on clinic attendances, hospital admissions, and child mortality. Lancet. 1993;342:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fawzi WW, Chalmers TC, Herrera MG, Mosteller F. Vitamin A supplementation and child mortality. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1993;269:898–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Vitamin A and Pneumonia Working Group. Potential interventions for the prevention of childhood pneumonia in developing countries: a meta-analysis of data from field trials to assess the impact of vitamin A supplementation on pneumonia morbidity and mortality. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73:609–619. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nacul LC, Kirkwood BR, Arthur P, Morris SS, Magalhaes M, Fink MCDS. Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled clinical trial of efficacy of vitamin A treatment in non-measles childhood pneumonia. BMJ. 1997;315:505–510. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7107.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussey GD, Klein M. A randomized, controlled trial of vitamin A in children with severe measles. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:160–164. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007193230304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coutsoudis A, Bobat RA, Coovadia HM, Kuhn L, Tsai W-Y, Stein ZA. The effects of vitamin A supplementation on the morbidity of children born to HIV-infected women. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1076–1081. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.8_pt_1.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO/CHD Immunisation-Linked Vitamin A Supplementation Study Group. Randomised trial to assess benefits and safety of vitamin A supplementation linked to immunisation in early infancy. Lancet. 1998;352:1257–1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberg AE, Dabis F, Marum LH, De Cock KM. HIV infection in Africa. In: Pizzo PA, Wilfert CM, editors. Pediatric AIDS—the challenge of HIV infection in children and adolescents. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nduati R, John G, Mbori-Ngacha D, Richardson B, Overbaugh J, Mwatha A, et al. Effect of breastfeeding and formula feeding on transmission of HIV-1: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2000;283:1167–1174. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.9.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, Kiselev P, Scott G, O'Sullivan MJ, et al. for the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group. Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment N Engl J Med 19943311173–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaffer N, Chuachoowong R, Mock PA, Bhadrakom C, Siriwasin W, Young NL, et al. for the Bangkok Collaborative Perinatal HIV Transmission Study Group. Short-course zidovudine for perinatal HIV-1 transmission in Bangkok, Thailand: a randomised controlled trial Lancet 1999353773–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dabis F, Msellati P, Meda N, Welffens-Ekra C, You B, Manigart O, et al. 6-month efficacy, tolerance, and acceptability of a short regimen of oral zidovudine to reduce vertical transmission of HIV in breastfed children in Côte d'Ivoire and Burkina Faso: a double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Lancet. 1999;353:786–792. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)11046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guay LA, Musoke P, Fleming T, Bagenda D, Allen M, Nakabiito C, et al. Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Kampala, Uganda: HIVNET 012 randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354:795–802. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thisyakorn U, Khongphatthanayothin M, Sirivichayakul S, Rongkavilit C, Poolcharoen W, Kunanusont C, et al. Thai Red Cross zidovudine donation program to prevent vertical transmission of HIV: the effect of the modified ACTG 076 regimen. AIDS. 2000;14:2921–2927. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200012220-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Msellati P, Hingst G, Kaba F, Viho I, Welffens-Ekra C, Dabis F. Operational issues in prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire 1998-1999. Feasibility of providing voluntary counselling and testing, short regimen with zidovudine and promoting alternatives to breastfeeding. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:641–647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.on behalf on the UNFPA/UNICEF/WHO/UNAIDS Inter-Agency Task Team on Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV. WHO Technical Consultation New data on the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and their policy implications: conclusions and recommendations at Geneva, 11-13 October 2000. 2001Geneva: WHO [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baggaley R, van Praag E. Antiretroviral interventions to reduce mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus: challenges for health systems, communities and society. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:1036–1044. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magesa SM, Wilkes TJ, Mnzava AE, Njunwa KJ, Myamba J, Kivuyo MD, et al. Trial of pyrethroid impregnated bednets in an area of Tanzania holoendemic for malaria. Part 2. Effects on the malaria vector population. Acta Trop. 1991;49:97–108. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(91)90057-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alonso PL, Lindsay SW, Armstrong JR, Conteh M, Hil AG, David PH, et al. The effect of insecticide-treated bed nets on mortality of Gambian children. Lancet. 1991;337:1499–1502. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93194-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D'Alessandro U, Olaleye BO, McGuire W, Langerock P, Bennett S, Aikins MK, et al. Mortality and morbidity from malaria in Gambian children after introduction of an impregnated bednet programme. Lancet. 1995;345:479–483. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90582-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nevill CG, Some ES, Mung'ala VO, Mutemi W, New L, Marsh K, et al. Insecticide-treated bednets to reduce mortality and severe morbidity from malaria among children on the Kenyan coast. Trop Med Int Health. 1996;1:139–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.1996.tb00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodman CA, Mills AJ. The evidence base on the cost-effectiveness of malaria control measures in Africa. Health Policy Plan. 1999;14:301–312. doi: 10.1093/heapol/14.4.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdulla S, Armstrong Schellenberg J, Nathan R, Mukasa R, Marchant TJ, Smith T, et al. Impact on malaria morbidity of a programme supplying insecticide-treated nets in children aged under 2 years in Tanzania: community cross sectional study. BMJ. 2001;322:270–273. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7281.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Working Group on Priority Setting; Council on Health Research and Development. Priority setting for health research: lessons from developing countries. Health Policy Plan. 2000;15:130–136. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Global Forum For Health Research. The 10/90 report on health research. Geneva: Global Forum for Health Research; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Council on Health Research and Development. The ENHR Handbook. A guide to essential national health research. Geneva: COHRED; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease: methods, results and projections. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pelletier DL, Frongillo EAJ, Schroeder DG, Habicht JP. The effects of malnutrition on child mortality in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73:443–448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization. WHO news and activities—Acute respiratory infections: the forgotten pandemic. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76:101–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kristensen I, Aaby P, Jensen H. Routine vaccinations and child survival: follow up study in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. BMJ. 2000;321:1435–1438. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7274.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Council on Health Research and Development; COHRED Working Group on Research to Action and Policy. Lessons in research to action, case studies from seven countries. Geneva: COHRED; 2000. [Google Scholar]