Abstract

Background and Aims

Since 1990, global child and infant mortality rates have typically stabilized or decreased due to improved healthcare, vaccination rollouts, and international funding. However, Afghanistan continues to face the highest child and infant mortality rates globally, with 43 deaths per 1000 live births. This study aims to examine the factors contributing to this high mortality rate and propose interventions to address the issue.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using databases such as Google Scholar and PubMed, focusing on articles published in English within the last 10 years (2013–2023). The search terms included “Child mortality,” “Infant mortality,” “SIDS,” “COVID‐19,” and “Afghanistan.” Original studies, systematic reviews, case studies, and reports meeting the inclusion criteria were selected for analysis. Additional sources from organizations such as UNICEF, the World Bank Group, WHO, and EMRO were also reviewed.

Results

The study findings reveal significant challenges contributing to Afghanistan's high infant and child mortality rates. These challenges include birth defects, preterm birth, malnutrition, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), traumatic injuries, fatal infections, infanticide, and abuse. The ongoing conflict, insecurity, and humanitarian crises further exacerbate the situation, leading to increased child casualties. Despite efforts by international agencies like UNICEF to provide vaccines and maternal education, the infant mortality rate remains high.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Afghanistan's child and infant mortality rates are of significant concern, and it is imperative that action be taken to reduce the incidence of child and infant mortality rates.

Keywords: Afghanistan, child mortality, infant mortality, public health

1. INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organisation(WHO) defines the infant mortality rate (IMR) as the likelihood of a child dying before reaching 1 year of age. 1 This rate is calculated by the number of infant deaths per 1000 live births. 2 It is a component of the child mortality rate, which refers to the number of deaths before reaching the age of 5. 1 These metrics plays a pivotal roles in assessing a country's healthcare infrastructure, socioeconomic status, and accessibility to high‐quality medical services. 1 Global child deaths have declined from 12.8 million per year in 1990, to 5 million in 2021. 3

Afghanistan faces significant challenges concerning its infant and child mortality rates, which serves as direct reflections of the nation's intricate socioeconomic and medical system. (Forde & Tripathi, 2022). Afghanistan contends with one of the world's highest infant mortality in 2021, experiencing 43 deaths per 1000 live births within the first year of life. 4 , 5 This rate remains unacceptably high, despite extensive efforts to enhance accessibility to essential reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health services. 6 This unpleasant reality not only compromises family well‐being but also impedes national development and international targets, for example the nation's progress reaching the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). 7 The 2023 SDGs progress report indicates Afghanistan ranks 158 out of 166 countries measured, and with major challenges remaining in addressing 15 out of the 17 goals. 8 Factors contributing to these persistently elevated rates include birth defects, preterm birth, malnutrition, Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), traumatic stress‐causing injuries, fatal infections, infanticide, and abuse. 5 , 9 These high rates continue despite the efforts of international agencies, such as United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), in providing vaccines and maternal education within the country. 4

The ongoing conflict and insecurity in Afghanistan have intensified crimes against children, such as kidnaping and displacement, making children even more vulnerable. 10 A child casualty report in 2021 reported the highest numbers of children killed and maimed in Afghanistan ever recorded. 10 The report also highlighted that out of every three civilians killed, one was a child. This backdrop of political instability and growing conflict has left children as the main casualties of violence, greatly increasing the child mortality rates in Afghanistan. 10 Furthermore, malnutrition remains a leading cause of child mortality in Afghanistan. 11 An estimated 45% of deaths among children less than 5 years of age in lower‐ and middle‐income families was linked to undernutrition. 11 With 95% of households in Afghanistan having inadequate intake of nutritious food, at least 1 million children were expected to die in 2021 of severe malnutrition. 11 Food insecurity, inadequate health care and lack of sanitation further exacerbates child malnutrition and contributes to preventable deaths and long term health consequences. 11 The critical need for comprehensive solutions and international cooperation to protect the lives and future opportunities of Afghani children is highlighted by these complex concerns.

In comparison, many higher‐income nations exhibit significantly lower IMR. As examples, the United States and Canada have 5 and 4 deaths per 1000 live births respectively. 4 This substantial disparity can be attributed to the higher quality levels of maternal and child healthcare, and support available for the wider population in richer countries. 5 , 9

This review aims to describe infant and child mortality rates in Afghanistan, along with the key contributing factors. Additionally, this review mentions newer interventions with better affordability and efficiency that can be used to manage the situation in Afghanistan. Furthermore, it proposes recommendations that can be implemented to address and improve these statistics.

2. METHODS

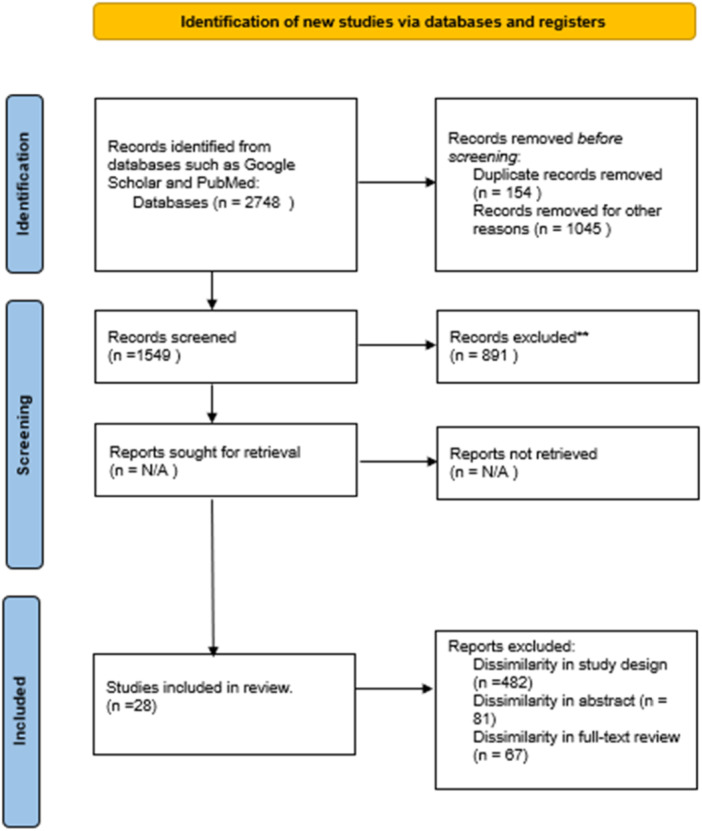

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was conducted to gather updated statistics on child and infant mortality rates in Afghanistan. The search also included articles highlighting effective strategies for reducing these mortality rates. Databases including Google Scholar and PubMed were utilized, employing the following search terms “Child mortality,” “Infant mortality,” “SIDS,” “COVID‐19,” and “Afghanistan.” The inclusion criteria included original research articles, systematic reviews, case studies, and reports published in English within the last 10 years (2013–2023). The exclusion criteria include articles available only as abstracts, those written before 2013, and those in languages other than English. Searches were also made of additional sources from websites, newspaper articles and reports including UNICEF, World Bank Group, WHO, EMRO (Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office). A summary of the included articles is shown in Table 1. Two authors (Qamar K and Salman Y) cross‐checked the included and excluded data, to ensure accuracy and consistency. A third author (Essar YM) was recruited to finalize the articles further in case of any disagreement between the former two authors. A Prisma chart (Figure 1) was used to identify, screen and include articles in this manuscript.

Table 1.

Summary of the articles included in the review.

| Author name | Title | Year | Journal | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forde IA et al. | Determinants of neonatal, postneonatal and child mortality in Afghanistan using frailty models | 2022 | Pediatric Research | Observational |

| Tharwani ZH et al. | Infant & Child Mortality in Pakistan and its Determinants: A Review | 2023 | INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing | Review |

| Rahmat ZS et al. | Child malnutrition in Afghanistan amid a deepening humanitarian crisis. | 2023 | International Health | Editorial |

| Najafizada SAM et al. | Social Determinants of Maternal Health in Afghanistan: A Review | 2017 | Central Asian Journal of Global Health. | Review |

| Thommesen T et al. | “The midwife helped me… otherwise I could have died”: women's experience of professional midwifery services in rural Afghanistan—a qualitative study in the provinces Kunar and Laghman. | 2020 | BioMed Central Pregnancy and Childbirth | Original |

| Almutairi A et al. | Morbidity and Mortality in Pakistan | 2016 | International Journal of Scientific & Technology Research | Original Study |

| Glass N et al. | The crisis of maternal and child health in Afghanistan. | 2023 | Conflict and Health. | Original study |

| Qamar K et al. | Mental health implications on Afghan children: an impending catastrophe. | 2021 | Global Mental Health | Editorial |

| Islam Z et al. | Afghanistan's humanitarian crisis and its impacts on the mental health of healthcare workers during COVID‐19. | 2021 | Global Mental Health. | Editorial |

| Thaler DS | Precision public health to inhibit the contagion of disease and move toward a future in which microbes spread health. | 2019 | BioMed Central Infectious Disease. | Original study |

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for updated systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers, and other sources.

3. RESULTS

The study findings reveal significant challenges contributing to Afghanistan's high infant and child mortality rates. These challenges include birth defects, preterm birth, malnutrition, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), traumatic injuries, fatal infections, infanticide, and abuse. The ongoing conflict, insecurity, and humanitarian crises further exacerbate the situation, leading to increased child casualties. Despite efforts by international agencies like UNICEF to provide vaccines and maternal education, infant mortality remains high. According to Forde IA et al. in their observational study, in 2022 they described very high rates of neonatal, postneonatal and child mortality due to many factors. Specifically this included breastfeeding status for neonatal and post‐natal groups, as the highest mortality in Afghanistan among neonates of 29.31% of live births were those who were not breast fed. High mortality was also observed in post‐neonates with mothers working in agricultural sites, resulting in a hazard ratio of 2.77 (95% CI 2.10, 3.65). 1 There are also statistics gathered by WHO in their Global Health Observatory on the probability of Infant mortality from birth to age 1 in 1000 live births, for 2021 the probability of infant death for both genders was 43.39 [ranging from 33.02 to 55.58], males exclusively was 46.51 [ranging from 35.38 to 59.77] and females exclusively was 40.18 [ranging from 30.46 to 51.63]. 2 Furthermore, on The World Bank open data for Infant mortality in Afghanistan, the general curve showed a decrease for all sexes neonatal mortality (43 per 1000 live births) for 2021, however the mortality rates of male infant were 47 per 1000 live births and female infant mortality rates were 40 per 1000 live births. 4 Another report from UN for Children and Armed Conflict during January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2020 claims that 5,770 children in Afghanistan had been killed or severely injured due to terrorist attacks. Terrorism groups also recruited around 260 male children to join them against the children's will. The reports also include 31 accounts of sexual violence and 69 abductions of predominantly male children. 10 This further extends to the problems Glass N et al. addressed in their study; among 131 Afghan health care workers in their study, the 81% of female health workers reported harassment due to terrorist reign. 38.1% of health care workers also reported the rise in sickness and malnutrition of children during 2021. 12 Zainab SR et al. mentions in their literature about the ongoing food insecurity and food related diseases in Afghanistan during 2022 as 14 million children under the age of 5, out of a population of more than 40 million, faced severe starvation that potentially causes death. 11

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Overview

Afghanistan's healthcare system faces significant challenges in addressing infant and child mortality. Despite efforts to improve healthcare infrastructure, a scarcity of evidence exists regarding this critical issue. Thus, this scoping review aims to shed light on the challenges while also proposing recommendations for enhancing infant and child survival rates in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan has the highest under‐five mortality rate in South Asia, a staggering 70.4 per 1000 live births. 1 Environmental variables such as maternal illnesses, radiation, and nutritional deficiencies such as folate and iodine can contribute to newborn mortality in developing countries, such as Pakistan, 9 with similar findings likely in Afghanistan though the true extent remains unknown. Anemia, insufficient access to vaccinations and inadequate medical checkups increases susceptibility to complications during pregnancy. These complications include premature ruptured membranes, pre/eclampsia, and postpartum hemorrhagic fatalities, with negative consequences for infant health outcomes. 13

The Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) in Afghanistan is responsible for executing the Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS), an efficacious approach to implementing primary health care within the country. BPHS strategically prioritises maternal and neonatal well‐being, child healthcare and immunization, public nutrition, mental health support, control of communicable diseases, and consistent provision of essential medications. However, local health system coverage across the country is inconsistent, with women often finding it difficult to access high‐quality healthcare. 13

UNICEF collaborates with the Ministry of Public Health to immunize every child, including the most vulnerable, against nine dangerous infectious diseases. They also work at the national level to establish and execute standardized newborn care recommendations. Every year, in Afghanistan, approximately 1.2 million children under the age of one and 6 million pregnant women receive vaccines that protect them from nine diseases. Despite UNICEF's efforts in reproductive, maternity, infant, and child health to expand services in existing facilities and reach mothers and children in rural settlements, infant mortality remains significant. 14

4.2. Significance of breastfeeding

Breast feeding practices are time sensitive determinants that impact mortality rates. There is an intricate link between not breastfeeding and mortality amongst newborns. It is a common issue among most poverty‐stricken countries to either prolong the first suckling of baby after delivery or shorten the years needed to breast feed (2 years or until baby can eat other foods). A newborn should not have any fluids except the breast milk for the first 6 months of life yet globally, more than 50% mothers do not follow this exclusive breast feeding routine. 15 The importance of breastfeeding becomes especially pronounced in the first year of a child's life, as predictors of mortality diminish with increasing age and size. 1

4.3. Birth defects

Home births without medical professionals or skilled attendants remain a common practice in Afghanistan. Currently births attended without a skilled health professional stand at 60% all over Afghanistan, where the highest rates of institutional deliveries lie in Central Afghanistan and lowest are at South Afghanistan. 16 In some provinces more than 61.4% of women do not have any medical assistance during labor. 16 Over 10% of Afghans must travel more than 2 h to obtain medical care, and this has an impact on the ability of pregnant women to access healthcare. 5 Sociocultural norms are that the head of the household, usually a male, is given the authority to make any decision, including any concerns around the health of the women in their household. This causes a delay in decision‐making and, as a result, in reaching the appropriate health care facility for deliveries. The restrictions imposed by the Afghan government on women's autonomy over their well‐being, and that of their child, further compounds risks associated with infant mortality. The collaborative efforts by UNICEF and other agencies focus on reducing infant death rates by providing newborn immunizations and educating young mothers, while also addressing the lack of sanitation, poor nutrition, and infections. These efforts are however limited in scope and therefore also limited in overall impact. Multiple gestations are a known risk factor for infant death, hence counseling on contraceptive techniques to use to avoid future unwanted pregnancies is provided. 5 Currently contraception is not a widely used method in Afghanistan for population control, it will require eradicating misconceptions and promoting its benefits among the civilians.

4.4. Topographical challenges

Afghanistan's challenging terrain causes formidable obstacles to both its citizens and medical professionals. The combination of severe weather patterns, difficult terrains, deeply ingrained social norms, and ongoing safety concerns has culminated in a shortage of adequately trained healthcare personnel and poor access to healthcare. 17 Health practitioners on the ground have consistently identified a series of ongoing issues. These include the persistent struggle to access quality care, a lack of training opportunities for healthcare workers, low pay, limited freedom for women, and inability to cover out‐of‐pocket healthcare costs. 17

4.5. Humanitarian crisis

Furthermore, a notable absence of a worldwide strategy for financial assistance, the continued sanctions and economic policies has exerted a significant toll on the country's overall economic health. This situation in turn has contributed significantly to the high mortality rates across all age groups. 12 In recent times, Afghanistan has become a focal point of numerous conflicts, precipitating a profound humanitarian crisis that has disrupted essential sectors such as healthcare and education. The multifaceted challenges arising from these conflicts have caused a significant deterioration in the functioning of crucial healthcare services and educational institutions. The culmination of these challenges was amplified following the 2021 takeover by the Taliban, a period marked by heightened instability and uncertainty. The confluence of factors has imposed unique hardships on Afghan children. In the face of economic hardships spurred by the circumstances, children are compelled to balance the demands of earning a livelihood to support their family with upholding their education. This is rooted in the belief among parents that achieving academic excellence holds the promise of a better poverty free future. However, the lack of child security casts a shadow over their development. Children are raised under the constant fear of violence, physical assault, child marriages and the exploitation of child labor. The accumulation of pressures, ranging from the weight of achievement to distressing realities of death and an uncertain future has resulted in prevalence of mental health disorders amongst these children. 18

Amidst the adversity, the people of Afghanistan managed to show resilience, the impact of the 12‐year‐long conflict has led to internal displacement of numerous families, particularly women and children. The consequence of this has exposed children to dangerous circumstances, rendering them vulnerable to criminal activities such as kidnaping, slavery and human trafficking. These risks remain an ever‐present cloud over their lives.

4.6. The impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on the health services

The COVID‐19 pandemic further exacerbated the challenges of infant and child mortality, compounding an already complex situation. The presence of a limited number of operational hospitals, coupled with shortage of active working staff and constrained humanitarian aid, has placed healthcare workers in Afghanistan at the forefront of vulnerability. These essential workers are primary targets of violence and mental health issues. Consequently the hostile environment has fostered workplace detachment and diminished self‐efficacy among healthcare professionals, impeding the ability to deliver optimal and high‐quality patient care. 19 Central to this issue is that a significant proportion of deaths are avoidable with a lack of timely application of appropriate care, treatments, and adoption of healthy behaviors (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summarizes the key points on infant and child mortality in Afghanistan.

| Issues | Details |

|---|---|

| High Under‐Five Mortality Rate | Staggering 70.4 per 1000 live births, influenced by environmental factors, maternal health, and nutritional deficiencies. |

| Healthcare System Challenges | MoPH's execution of BPHS for primary healthcare. Inconsistent local health system coverage, difficult access for women to high‐quality healthcare. Limited education amongst guardians/parents towards child birth and health. Many misconceptions towards health‐care. |

| Significance of Breastfeeding | Breastfeeding as a crucial determinant impacting mortality, with over 50% mothers globally not following exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months. |

| Birth Defects and Home Births | 60% of births without skilled health professionals. Sociocultural norms and governmental restrictions compound risks associated with infant mortality. |

| Topographical Challenges | Difficult terrain and social norms leading to healthcare personnel shortage and poor healthcare access. |

| Humanitarian Crisis | Economic challenges and conflicts leading to deteriorated healthcare services and educational institutions. Children facing violence, assault, and exploitation. |

| COVID‐19 Pandemic Impact | Limited hospitals, staff shortages, and constrained aid worsening healthcare challenges. Healthcare workers facing violence and mental health issues. |

Despite the recent improvements in reducing child and infant mortality rates, there are still gaps that need major attention from the Afghan government. The need for rigorous surveillance and real‐time data is clear, to better reflect the true numbers of child and infant mortality rates in remote areas of the country. This requires major investment in the healthcare and public health infrastructure.

4.7. Recommendations

Infant and child mortality in Afghanistan represents critical concerns that imperil the nation's population growth. Although the rates of infant and child mortality have decreased in recent years, Afghanistan still has the highest rate in the world, accounting 43 deaths per 1000 live births. 5 This demands the need to take urgent stance in reducing the mortality. While currently there have been some policies and implementations of foreign aid, spreading awareness and media coverage, it has not been efficient to manage Afghanistan's threats to infant and child lives. There are several recommendations that can be implemented to address these challenges.

Firstly, prioritising surveillance is paramount as this will help to meticulously collect data, especially specific regions within Afghanistan grappling with the highest infant and child mortality rates. This information would enable targeted investigations to unveil the underlying causes threatening the lives of children in these areas. This builds upon the principles of precision public health, where resources are very specifically targeted to the areas of highest needs, and these approaches can best be informed by provision of timely data. 20 Basic health needs cross‐sectional surveys across a range of populations can identify specific and broader issues that require prioritisation, within the limited health service resources available.

Socioeconomic factors can be considered to reconnect family units and support child safety. In January 2020 the Child Protection Area of Responsibility (CP AoR) by UNICEF in Afghanistan managed to trace and reunite 3974 displaced children to their families. 21 With consistency, even more lost children will be able to reunite with their families, reducing their vulnerability.

On the national level, collaboration between the Afghan government, international organizations, and NGOs is necessary to augment healthcare access for all Afghans. This includes expanding the number of healthcare facilities, training a larger cohort of healthcare professionals and providing financial assistance to families in need. Similarly, preventing healthcare professionals from becoming overwhelmed is pivotal, as their stress levels can detrimentally affect the quality of care provided. In rural areas especially, the establishment of additional healthcare facilities are essential to ensure swift access to neonatal and pediatric services, especially during emergencies. In 2002, a government reform called System Enhancement for Health Action in Transition (SEHAT) program by Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) opened clinics at Tupchi Village, Bamyan City, Afghanistan. 22 This is a rural area and the clinic aids almost 1800 patients per month, the program aims to improve health, nutrition, and family planning all over Afghanistan. 22 This health system model can potentially be adapted and adopted across other areas of the country. Ultimately, the Afghanistan government does need ro invest in itself health services, with could bring increased support from international donors.

Other factors include investing in education, fostering job creation, and establishing a robust social safety net. Hospitals and clinics should have donation drives and funding programs to support patients who are financially constrained. In India, Poverty Eradication Programs begun during 2000s where the government and private beneficiaries collaborated to make significant long‐term and short‐term improvements to bring its people above poverty line. This included improving rural infrastructure, utilizing agricultural industry, creating job opportunities, increasing education, providing food and shelter. 23 Similarly in Afghanistan such initiatives may effectively reduce poverty and financial struggles.

Also, addressing malnutrition is vital, this can be achieved through the establishment of food camps that offer staple foods like wheat, rice, meat, fruits, and vegetables. The World Food Program (WFP) works towards providing nutritious food globally. In USA, SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) WIC (Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children) function through electronic bank transfer cards, financially supporting low‐income families to access food. 24 , 25 Over a few years SNAP has helped 42 million families with food insecurity which improved overall health of Americans and reportedly reduced health care cost. 25 Similar models, that have the potential to be deployed in low‐resource environments, such as Afghanistan, can be considered.

The Afghan government must prioritise education, ensuring that every child has access to free and compulsory education, irrespective of their gender or socioeconomic status. This holistic approach will contribute to children's safety and provide a protective shield against various forms of child endangerment such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse. Furthermore, awareness must be provided to all families with children aged 0–15, educating them about the manifold threats to children's health. This education encompasses the importance of routine vaccinations, such as those provided by the Expanded Program on immunization (EPI), as well as prompt recognition of danger signs, and basic home management of common health complaints. A meta‐analysis and systematic review from Lancet reports a strong correlation between parental education and child survivability, as a mother with 12 years of education has a 31% lower risk of her child dying before turning 5 than a mother with 0 years of education. 26 Contributing factors included how educated parents have better life‐saving strategies, better communication with physicians, early detection of danger signs towards child health, and a better family planning strategy. A mother's education is also important as it empowers her own health‐related decision‐making, for both herself and her child,

In Afghanistan, awareness is also necessary for women during pregnancy to receive all maternal vaccines for TORCH (Toxoplasmosis, Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, Herpes and Other agents) infections as it commonly leads to neonatal birth defects or death. The pregnant mothers must also ensure taking supplements for vitamins and minerals to prevent common congenital abnormalities such as neural tube defects, retinal blindness, intrauterine growth retardation, cognitive impairment, cretinism, and malnutrition. 27 Currently many families in Afghanistan are hesitant to take precautionary decisions towards maternal and fetal health. Thus, concerted efforts to improve population trust with healthcare workers and other stakeholders is vital, to counter misinformation, suspicions, and paranoia. Enhanced health promotion and public health messaging for vaccinations, supplementations, breast feeding, umbilical cord hygiene and regular follow ups are necessary, for example to reduce postnatal complications of neonate and mother.

In many cases, fatal outcomes result due to inadequacy of health services. To improve the clinical care, it is crucial to prioritise early detection and management of risk factors for infant and child mortality, such as maternal malnutrition and prenatal infections. This can be achieved through the integration of maternal and child health services, routine screening programs, and community‐based interventions. Additionally, capacity‐building initiatives for healthcare providers, including training in neonatal resuscitation and emergency obstetric care, are essential to improve clinical outcomes and reduce mortality rates. Furthermore. mobile health apps and other digital tools can be used to educate people about health and hygiene, provide information about healthcare services, and connect people with healthcare providers. 28 Digital health services have the potential to answer any questions or information patients are too conservative or nervous to ask physicians (e.g., sensitive topics such as contraception). Emergency care can also be improved by enhanced communication and transport systems.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, Afghanistan's child and infant mortality rates are of significant concern and it is imperative that action be taken. The rates are substantially higher than those of other countries, especially developed countries. The causes for these high rates include birth defects, preterm birth, malnutrition, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), traumatic stress‐causing injuries, fatal infections, infanticide, and abuse. It is essential for more international humanitarian aid and support, nationally‐delivered health system improvements, as well as action by the local government and more funding, to help alleviate these rates and improve the overall healthcare available to mothers and children.

ETHICS APPROVAL

Our study did not require an ethical board approval because it is a narrative review.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Khulud Qamar: Writing ‐ original draft; Writing ‐ review & editing. Mohammad Yasir Essar: Conceptualization; Writing ‐ review & editing; Supervision. Javeria Arif Siddiqui: Writing ‐ original draft. Ariba Salman: Writing ‐ original draft. Yumna Salman: Writing ‐ original draft. Michael G Head: Writing ‐ review & editing.

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

The lead author Mohammad Yasir Essar affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Qamar K, Essar MY, Siddiqui JA, Salman A, Salman Y, Head MG. Infant and child mortality in Afghanistan: A scoping review. Health Sci Rep. 2024;7:e2224. 10.1002/hsr2.2224

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study. All data are available in the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Forde IA, Tripathi V. Determinants of neonatal, post‐neonatal and child mortality in Afghanistan using frailty models. Pediatr Res. 2022;91(4):991‐1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Infant mortality rate (between birth and 11 months per 1000 live births) [Internet] . Accessed August 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/infant-mortality-rate-(probability-of-dying-between-birth-and-age-1-per-1000-live-births)

- 3. Child mortality and causes of death [Internet] . Accessed September 22, 2023. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/child-mortality-and-causes-of-death

- 4. World Bank Open Data [Internet] . World Bank Open Data. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://data.worldbank.org

- 5. Philipp J. Everything to know about infant mortality in Afghanistan [Internet] The Borgen Project. 2023. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://borgenproject.org/infant-mortality-in-afghanistan/

- 6. afghanistan . World Health Organization ‐ regional office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Reducing maternal, neonatal and child deaths in Afghanistan. Accessed August 26, 2023. http://www.emro.who.int/afg/afghanistan-news/action-plan-reduction-mortality.html

- 7. UNICEF DATA [Internet] . Child‐Related SDG Progress Assessment for Afghanistan. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://data.unicef.org/sdgs/country/afg/

- 8. Sustainable Development Report 2023 [Internet] . Accessed December 26, 2023. https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/

- 9. Tharwani ZH, Bilal W, Khan HA, et al. Infant & child mortality in Pakistan and its determinants: a review. Inquiry. 2023;60:469580231167024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vinet F. Aghanistan: alarming scale of grave violations against children as current security situation collapses, country facing the unknown [Internet]. Accessed September 22, 2023. https://childrenandarmedconflict.un.org/2021/08/138737/

- 11. Rahmat ZS, Rafi HM, Nadeem A, Salman Y, Nawaz FA, Essar MY. Child malnutrition in Afghanistan amid a deepening humanitarian crisis. Int Health. 2023;15(4):353‐356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Glass N, Jalalzai R, Spiegel P, Rubenstein L. The crisis of maternal and child health in Afghanistan. Confl Health. 2023;17(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Najafizada SAM, Bourgeault IL, Labonté R. Social determinants of maternal health in Afghanistan: a review. Cent Asian J Glob Health. 2017;6(1):240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Health | UNICEF Afghanistan [Internet] . Accessed August 26, 2023. https://www.unicef.org/afghanistan/health

- 15. Breastfeeding [Internet] . Accessed September 18, 2023. https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding

- 16. Thommesen T, Kismul H, Kaplan I, Safi K, Van den Bergh G. “The midwife helped me otherwise I could have died”: women's experience of professional midwifery services in rural Afghanistan—a qualitative study in the provinces Kunar and Laghman. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2020;20(1):140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Almutairi A. Morbidity and mortality in Afghanistan. Int J Sci Technol Res. 2016;5(09):164‐165. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Qamar K, Priya M, Rija A, Vohra LI, Nawaz FA, Essar MY. Mental health implications on Afghan children: an impending catastrophe. Glob Ment Health. 2022;9:397‐400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Islam Z, Rija A, Mohanan P, et al. Afghanistan's humanitarian crisis and its impacts on the mental health of healthcare workers during COVID‐19. Glob Ment Health. 2022;9:61‐64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Thaler DS, Head MG, Horsley A. Precision public health to inhibit the contagion of disease and move toward a future in which microbes spread health. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Afghanistan Child Protection AoR, Response Monitoring Dashboard Jan ‐ Nov 2020 ‐ Afghanistan | ReliefWeb [Internet]. 2020. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://reliefweb.int/report/afghanistan/afghanistan-child-protection-aor-response-monitoring-dashboard-jan-nov-2020

- 22.Healthcare Reforms Bring Results in Afghanistan's Bamyan Province [Internet]. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2021/01/28/government-reforms-in-health-care-show-results-in-bamyan-province

- 23.(19) (PDF) An overview of poverty eradication programmes in India [Internet]. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326065825_An_overview_of_poverty_eradication_programmes_in_India

- 24.SNAP/WIC Communications and Advocacy Toolkit | National Recreation and Park Association [Internet]. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://www.nrpa.org/publications-research/best-practice-resources/snap-and-wic-outreach-toolkit/snapwic-communications-and-advocacy-toolkit/

- 25.SNAP Is Linked with improved nutritional outcomes and lower health care costs | Center on Budget and Policy Priorities [Internet]. 2018. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-is-linked-with-improved-nutritional-outcomes-and-lower-health-care

- 26.Parental education and inequalities in child mortality: a global systematic review and meta‐analysis ‐ the Lancet [Internet]. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)00534-1/fulltext#seccestitle140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Policy ‐ Strategy for the prevention and control of vitamin and mineral deficiencies in Afghanistan | Global database on the Implementation of Nutrition Action (GINA) [Internet]. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/en/node/17841

- 28.How digital health can help refugees access medical care | MobiHealthNews [Internet]. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://www.mobihealthnews.com/news/how-digital-health-can-help-refugees-access-medical-care

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study. All data are available in the manuscript.