ABSTRACT

Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors (IP3Rs) are high-conductance channels that allow the regulated redistribution of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the cytosol and, at specialized membrane contact sites (MCSs), to other organelles. Only a subset of IP3Rs release Ca2+ to the cytosol in response to IP3. These ‘licensed’ IP3Rs are associated with Kras-induced actin-interacting protein (KRAP, also known as ITPRID2) beneath the plasma membrane. It is unclear whether KRAP regulates IP3Rs at MCSs. We show, using simultaneous measurements of Ca2+ concentration in the cytosol and mitochondrial matrix, that KRAP also licenses IP3Rs to release Ca2+ to mitochondria. Loss of KRAP abolishes cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ signals evoked by stimulation of IP3Rs via endogenous receptors. KRAP is located at ER–mitochondrial membrane contact sites (ERMCSs) populated by IP3R clusters. Using a proximity ligation assay between IP3R and voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1), we show that loss of KRAP reduces the number of ERMCSs. We conclude that KRAP regulates Ca2+ transfer from IP3Rs to mitochondria by both licensing IP3R activity and stabilizing ERMCSs.

Keywords: Ca2+, Endoplasmic reticulum, HeLa cell, Histamine, IP3 receptor, KRAP, MCU, Membrane contact site, Mitochondria, Proximity ligation assay, VDAC1

Summary: KRAP regulates transfer of Ca2+ from IP3 receptors to mitochondria by both stabilizing membrane contact sites between the ER and mitochondria and licensing IP3 receptors to respond to IP3 at these junctions.

INTRODUCTION

Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors (IP3Rs) are Ca2+ channels expressed in the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where their opening, after binding of IP3 and Ca2+, allows Ca2+ to leak rapidly from the ER (Foskett et al., 2007; Prole and Taylor, 2019b). The Ca2+ released can then diffuse into the cytosol to increase the cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, which can then regulate diverse cellular activities. Ca2+ can also be delivered to other membranes to which the ER is closely apposed at membrane contact sites (MCSs) (Helle et al., 2013; Roest et al., 2017). Opening of IP3Rs within MCSs between the ER and lysosomes or mitochondria, for example, delivers Ca2+ locally at concentrations sufficient to fuel uptake by the low-affinity Ca2+ uptake systems of these organelles (De Stefani et al., 2011; Atakpa et al., 2018). The most thoroughly studied of these exchanges occurs within ER–mitochondrial MCSs (ERMCSs), where IP3Rs deliver Ca2+ to the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU), thereby shaping cytosolic Ca2+ signals and regulating mitochondrial function and cell fate (Kirichok et al., 2004; Mendes et al., 2005; De Stefani et al., 2011; Rowland and Voeltz, 2012; Bartok et al., 2019; Vecellio Reane et al., 2020). Recent observations suggest that all three IP3R subtypes (IP3R1–3) localize to ERMCSs and support Ca2+ delivery to mitochondria (Bartok et al., 2019). ERMCSs are held together by tethers (Vecellio Reane et al., 2020), with tripartite interactions among IP3Rs, the anchoring cytosolic protein GRP75 (also known as HSPA9) and the voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1 (VDAC1) in the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), most thoroughly implicated in regulating Ca2+ transfer (Gincel et al., 2001; Rapizzi et al., 2002; De Stefani et al., 2012). Disruption of ERMCSs is implicated in neurodegenerative diseases (Milakovic et al., 2006; Area-Gomez et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2021), metabolic disorders (Tubbs and Rieusset, 2017) and cancer (Simoes et al., 2020).

Only a fraction of the IP3Rs expressed in a cell (∼30% in HeLa cells) release Ca2+ into the cytosol in response to IP3; these have been described as ‘licensed’ IP3Rs (Thillaiappan et al., 2017). Evidence that Kras-induced actin-binding protein (KRAP; also known as IP3 receptor-interacting domain-containing protein 2 or ITPRID2) associates with IP3Rs and actin (Fujimoto et al., 2011a,b) and perhaps influences Ca2+ release (Fujimoto et al., 2011c) prompted further analysis of its role in licensing IP3Rs. KRAP is ubiquitously expressed, its amino acid sequence is well-conserved across species (Inokuchi et al., 2004; Fujimoto et al., 2007; Fujimoto and Shirasawa, 2011), its interaction with IP3R requires a double phenylalanine motif within the N-terminal region of KRAP (Fujimoto et al., 2011b), and loss of KRAP alters the subcellular distribution of IP3Rs (Fujimoto et al., 2011a; Thillaiappan et al., 2021). It is now clear that licensed IP3Rs are tethered in small clusters by KRAP to actin near the plasma membrane and adjacent to the sites where store-operated Ca2+ entry occurs (Thillaiappan et al., 2021; Vorontsova et al., 2022).

Loss of KRAP abolishes the cytosolic Ca2+ signals evoked by IP3Rs, which are initiated by KRAP-licensed IP3Rs parked immediately beneath the plasma membrane (PM). The functions of the many IP3Rs that are neither immobilized nor associated with KRAP are unresolved (Thillaiappan et al., 2021). It is not known, for example, whether the IP3Rs that transfer Ca2+ at MCSs to the cytosolic surface of organelles are, similar to the IP3Rs that evoke cytosolic Ca2+ signals, licensed by KRAP. As the positioning of IP3Rs within specialized ERMCSs is critical for transfer of Ca2+ via MCU (Kirichok et al., 2004; Mendes et al., 2005; De Stefani et al., 2011; Rowland Voeltz, 2012; Bartok et al., 2019; Vecellio Reane et al., 2020), we assessed whether KRAP also regulates the IP3Rs that transport Ca2+ at these MCSs. The role of KRAP at ERMCSs has not hitherto been studied.

Here, we show that KRAP both regulates the activity of the IP3Rs that deliver Ca2+ to mitochondria and structurally stabilizes the ERMCSs. We conclude that KRAP exerts a dual regulation of Ca2+ transfer from ER to mitochondria.

RESULTS

IP3-evoked cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ signals require KRAP

We used validated Ca2+ indicators to simultaneously record the free Ca2+ concentrations in the cytosol ([Ca2+]c) and mitochondrial matrix ([Ca2+]m) of single HeLa cells (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1; Materials and Methods). Stimulation of HeLa cells in Ca2+-free HEPES-buffered saline (HBS) with a maximally effective concentration of histamine to evoke IP3 formation through endogenous receptors caused a rapid increase in both [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m (Fig. 1B). Pre-treatment of cells with carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) to dissipate the H+ gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane had no effect on the histamine-evoked increase in [Ca2+]c, but it almost abolished the increase in [Ca2+]m (Fig. 1C). We used siRNA to reduce expression of MCU by 78±7% (mean±s.e.m.) (Fig. 1D). This treatment almost abolished the histamine-evoked increase in [Ca2+]m without significantly affecting the increase in [Ca2+]c (Fig. 1E–G). These results, which are consistent with many published observations (Rapizzi et al., 2002; De Stefani et al., 2011, 2012; Bartok et al., 2019; Katona et al., 2022), confirm that IP3-evoked Ca2+ release causes rapid uptake of Ca2+ into mitochondria via MCU.

Fig. 1.

Histamine evokes transfer of Ca2+ from the ER to mitochondria through IP3Rs. (A) Wide-field fluorescence images of HeLa cells expressing TOM20–GFP (green) and Mito-R-GECO1 (pseudo-coloured in magenta); the overlay shows colocalization in white. Images are typical of four independent experiments. Manders' coefficients for the fraction of Mito-R-GECO1 colocalizing with TOM20–GFP=0.88±0.07 (mean±s.d.), n=4. (B) HeLa cells expressing Mito-R-GECO1 (mitochondrial Ca2+ indicator) and loaded with Calbryte 520 (cytosolic Ca2+ indicator) were stimulated with histamine (100 µM) in Ca2+-free HBS. Fluorescence from the Ca2+-saturated indicators (Fmax) was determined by addition of CGP 37157 (CGP, 50 µM) to inhibit the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and then ionomycin (Iono, 10 μM) with 20 mM CaCl2. Results (F/Fmax) show fluorescence recorded from an entire cell. Results are typical of at least ten experiments. (C) Summary results show peak changes in fluorescence (ΔF/Fmax) evoked by histamine (100 µM) alone, or after pre-incubation with FCCP (5 µM, 10 min). Results show values for individual cells and mean±s.d. from ten (control) or 15 cells (FCCP) from three independent experiments. ns, not significant, P>0.05; **P<0.01; one-way ANOVA with Tukey's correction. (D) Western blots showing the effect of non-silencing (NS) siRNA or siRNA directed at MCU in HeLa cells. Protein loadings (μg/lane) and molecular mass markers (kDa) are shown. Results are typical of three independent experiments. MCU siRNA reduced MCU expression to 22±7% of its expression in cells treated with NS siRNA (mean±s.e.m., n=3). (E,F) Effects of histamine (100 µM) in Ca2+-free HBS on [Ca2+]c (Calbryte 520) (E) or [Ca2+]m (Mito-R-GECO1) (F) in single HeLa cells treated with NS or MCU siRNA. Results, reported as F/Fmax, are typical of 15–16 cells from three independent experiments. (G) Summary results show effects of histamine in HeLa cells treated with NS or MCU siRNA. Results (individual values, mean±s.d.) are from 16 (NS) or 15 cells (MCU siRNA) from three independent experiments. ns, not significant, P>0.05; **P<0.01; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction.

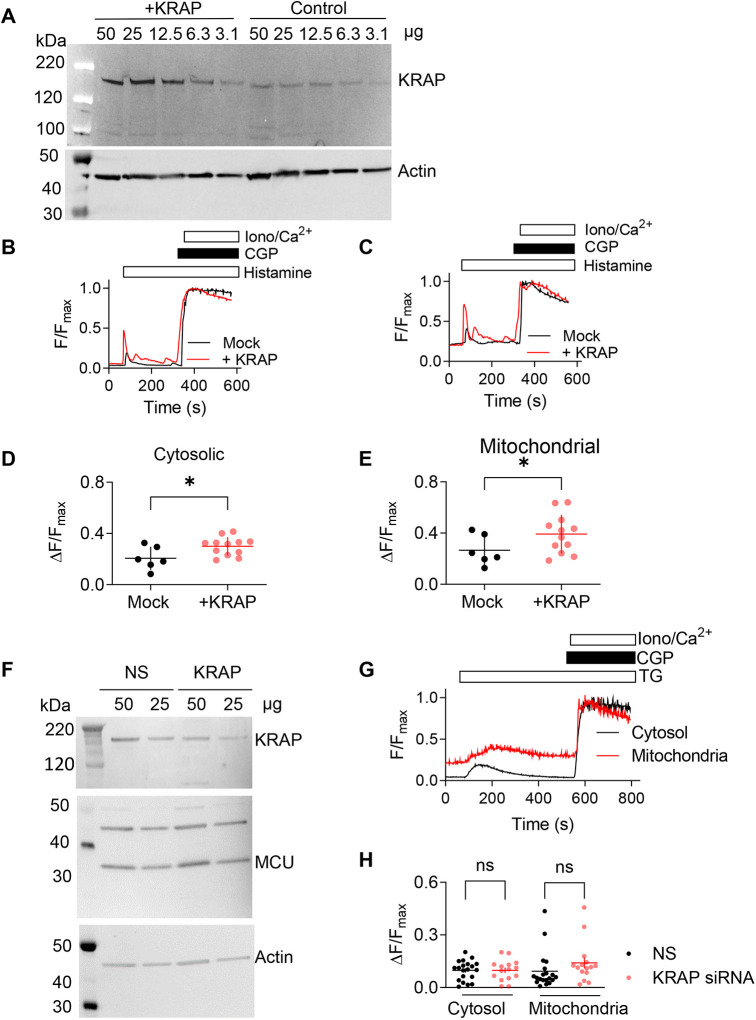

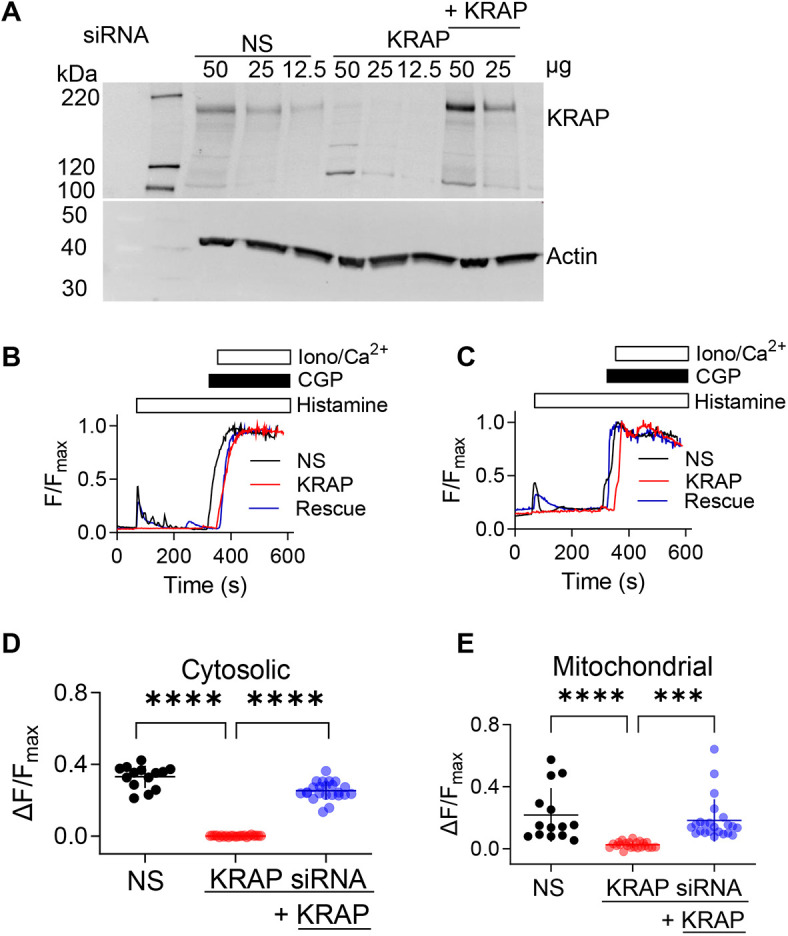

Treatment of HeLa cells with an appropriate siRNA caused a substantial (83±9%, mean±s.e.m.) reduction in KRAP expression (Fig. 2A) and abolished the histamine-evoked increases in both [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m. Both responses were rescued by expression of a siRNA-resistant KRAP (Fig. 2B–E). Furthermore, overexpression of KRAP in HeLa cells (352±32% of control levels, mean±s.e.m.) exaggerated the histamine-evoked increases in both [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m (Fig. 3A–E). We conclude that both the global cytosolic Ca2+ signals evoked by IP3 and the uptake of Ca2+ by mitochondria through MCU require KRAP.

Fig. 2.

KRAP is required for transfer of Ca2+ from the ER to mitochondria through IP3R. (A) Western blots from HeLa cells showing the effect of NS siRNA or siRNA directed at KRAP alone or after expression of siRNA-resistant KRAP. Results are typical of four experiments. Protein loadings (μg/lane) and molecular mass markers (kDa, left) are shown. (B,C) Effects of histamine (100 µM) in Ca2+-free HBS on [Ca2+]c (Calbryte 520) (B) or [Ca2+]m (Mito-R-GECO1) (C) in single HeLa cells treated with NS siRNA, KRAP siRNA or KRAP siRNA with siRNA-resistant KRAP (‘rescue’). Results, reported as F/Fmax, are typical of 14–23 cells from three independent experiments. (D,E) Summary results show peak changes in fluorescence (ΔF/Fmax) from cytosolic (D) or mitochondrial (E) Ca2+ indicators. Results show individual values with mean±s.d. from 14 (NS siRNA), 23 (KRAP siRNA) and 23 cells (rescue) from three independent experiments. ***P<0.001; ****P<0.0001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction.

Fig. 3.

KRAP regulates IP3R-mediated transfer of Ca2+ from the ER to mitochondria without affecting MCU. (A) Western blots from control HeLa cells and after overexpression of KRAP. KRAP expression was 3.5±0.3-fold greater in cells overexpressing KRAP (mean±s.e.m., three independent analyses). Protein loadings (μg/lane) and molecular mass markers (kDa) are shown. (B,C) Effects of histamine (100 µM) in Ca2+-free HBS on [Ca2+]c (Calbryte 520) (B) or [Ca2+]m (Mito-R-GECO1) (C) in single HeLa cells overexpressing KRAP or after mock transfection with an empty vector. (D,E) Summary results show peak changes in cytosolic (D) and mitochondrial (E) fluorescence from Ca2+ indicators evoked by histamine (100 µM) in HeLa cells overexpressing KRAP or after mock transfection. Individual values with mean±s.d. are shown from six (mock) or 12 (KRAP) cells. Cells were transfected with plasmids expressing Mito-R-GECO and KRAP (in a 1:3 ratio), and all cells expressing Mito-R-GECO in the field were included in the analysis. *P<0.05; two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. (F) Western blots from HeLa cells showing the effect of NS siRNA or siRNA directed against KRAP on the expression of MCU. KRAP expression was reduced by 70±6% (mean±s.e.m.). MCU expression was 97±24% of its level in NS siRNA-treated cells. P>0.05; two-tailed paired Student's t-test of MCU expression in KRAP siRNA-treated cells compared to that in NS siRNA-treated cells from six independent experiments. (G) HeLa cells expressing Mito-R-GECO1 and loaded with Calbryte 520 were stimulated with thapsigargin (TG, 5 µM) in Ca2+-free HBS, and then CGP 37157 (CGP, 50 µM) and ionomycin (Iono, 10 μM) with 20 mM CaCl2 to obtain Fmax. Results (F/Fmax) show fluorescence recorded from an entire cell for each indicator. Results are typical of at least three experiments. (H) Summary results show peak changes in fluorescence (ΔF/Fmax) from cytosolic or mitochondrial Ca2+ indicators evoked by thapsigargin (5 µM). Mean±s.d. (and individual values) are shown from 20 (NS siRNA) and 15 (KRAP siRNA) cells from three independent experiments. ns, not significant, P>0.05; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction.

KRAP is required for delivery of Ca2+ from IP3R to mitochondria

We next considered whether the requirement for KRAP for mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake arises from KRAP regulating delivery of Ca2+ to the OMM and/or regulation of MCU. Treatment of HeLa cells with KRAP siRNA had no effect on MCU expression [MCU expression was 97±24% of its level in non-silencing (NS) siRNA-treated cells, mean±s.e.m., n=6] (Fig. 3F) or mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. S2). HeLa cells were stimulated with thapsigargin in Ca2+-free HBS to promote loss of Ca2+ from the ER, which is independent of IP3R activity. Thapsigargin evoked increases in both [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m, but neither response was affected by siRNA-mediated loss of KRAP expression (Fig. 3G,H).

These results establish that KRAP is required for mitochondria to accumulate Ca2+ released through IP3Rs. Furthermore, the deficient Ca2+ transfer in the absence of KRAP is not due to collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential, loss of MCU expression or compromised function of MCU.

KRAP mediates association of IP3R with mitochondria

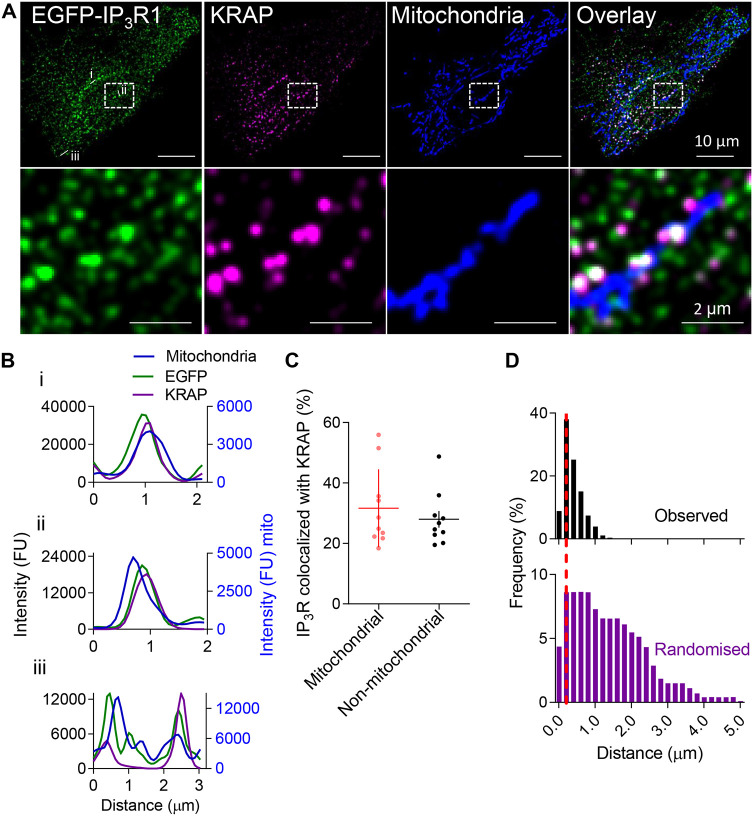

We used HeLa cells in which endogenous IP3R1 (encoded by ITPR1) was tagged with EGFP (EGFP–IP3R1 HeLa cells), an antibody to KRAP and MitoTracker to explore the relationships among IP3Rs, mitochondria and KRAP. Although only IP3R1 is visible in EGFP–IP3R1 HeLa cells, it is the major IP3R subtype in these cells (Itzhak et al., 2016) and it assembles into tetrameric channels with the other subtypes (Thillaiappan et al., 2017). We assume, therefore, that EGFP identifies most IP3Rs in EGFP–IP3R1 HeLa cells (Thillaiappan et al., 2021). Confocal microscopy established that 24±11% of EGFP–IP3Rs (mean±s.d., n=10 cells) were associated with mitochondria and many of these IP3R puncta were associated with KRAP (Fig. 4A,B). Quantitative analyses using an object-based method (Gilles et al., 2017) established that the colocalization of KRAP with IP3Rs was indistinguishable for IP3Rs associated with mitochondria (32±13%, mean±s.d., n=10) and for IP3Rs with no mitochondrial association (28±9%, n=10) (Fig. 4C). Analysis of nearest-neighbour distances revealed that IP3Rs affiliated with mitochondria were significantly more colocalized with KRAP compared to randomly distributed IP3R puncta (Fig. 4D). These results establish that a significant fraction of the IP3Rs that associate with mitochondria are also associated with KRAP. Our conclusion is consistent with a proteomic analysis that identified KRAP near the OMM (Hung et al., 2017).

Fig. 4.

Colocalization of KRAP and IP3R with mitochondria. (A) Confocal section near the plasma membrane of an EGFP–IP3R1 HeLa cell loaded with MitoTracker Deep Red (pseudo-coloured in blue) and immunostained for KRAP (magenta). GFP Booster was used to enhance the fluorescence intensity of the EGFP signal. Images show some IP3R puncta (green) colocalized with KRAP (white where colocalized) associated with mitochondria. Boxed regions are enlarged below. Images are typical of ten cells. (B) Fluorescence intensity profiles of EGFP–IP3R1, KRAP and mitochondria from the regions marked by white lines and labelled i–iii in A. FU, fluorescence units. (C) Percentage of mitochondria-associated IP3R puncta or non-mitochondria-associated IP3R puncta that colocalize with KRAP (centre-to-centre separations <233 nm). Results show individual values with mean±s.d. for ten cells. P>0.05; two-tailed paired Student's t-test. (D) Frequency distributions of centre-to-centre distances for mitochondria-associated IP3R puncta (2071 puncta from ten cells) and the nearest KRAP punctum. Observed values and values after randomization of positions of the KRAP puncta (100 iterations) are shown. 31.7±12.9% (mean±s.d., n=10 cells) of IP3R puncta are within 233 nm (red line) of a KRAP punctum (5.2±2.7% after randomization; P<0.0001, two-tailed paired Student's t-test). Images and results are representative of ten independent dishes.

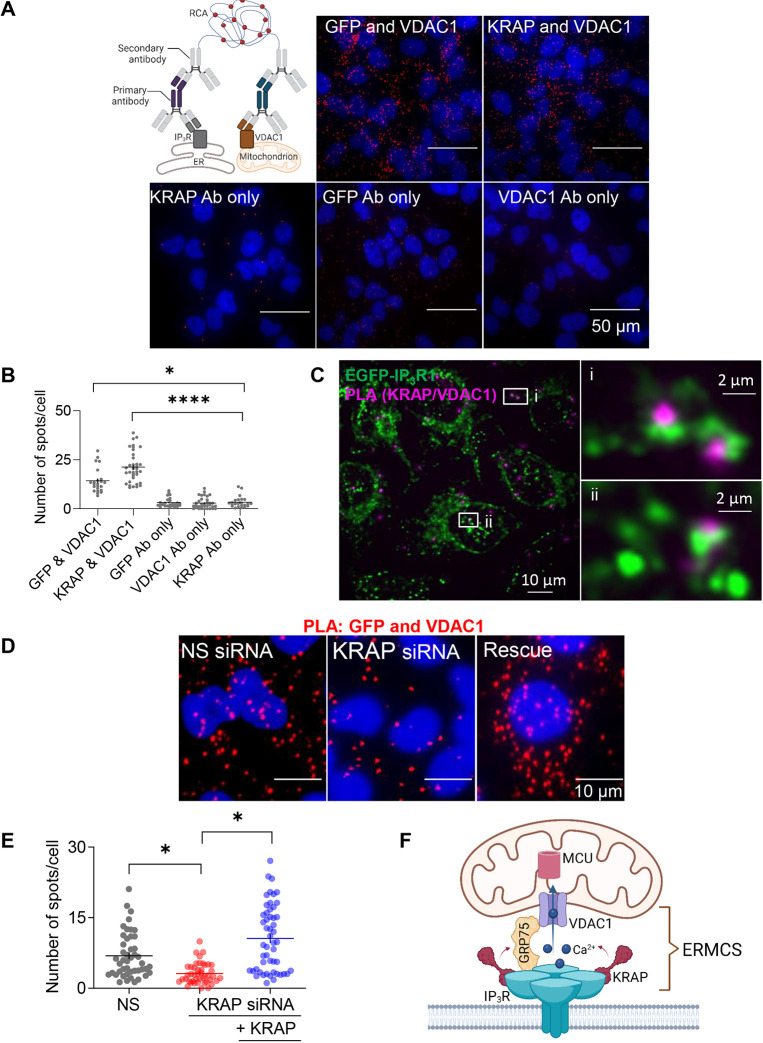

We used proximity ligation assays (PLAs), which detect proteins closer than about 40 nm (Tubbs and Rieusset, 2016), to examine the association of VDAC1, a protein embedded in the OMM, with IP3Rs and KRAP. The results demonstrate that VDAC1 is in close proximity to both IP3Rs and KRAP in EGFP–IP3R1 HeLa cells (Fig. 5A,B). Furthermore, EGFP–IP3R puncta and the PLA spots indicative of KRAP and VDAC1 proximity were significantly colocalized (Manders' split coefficient, 0.82±0.15; n=7 cells, Costes' P-value, 100%) (Fig. 5C). These results confirm that many IP3Rs that are affiliated with mitochondria are closely associated with KRAP.

Fig. 5.

KRAP contributes to the association of IP3R with mitochondria. (A) Proximity ligation assay (PLA) uses primary antibodies that recognize proteins in the ER or mitochondrial membranes. Hybridization of complementary oligonucleotides conjugated to secondary antibodies occurs if the primary antibodies are within ∼40 nm of each other. Ligation of the hybridized strands then allows rolling circle amplification (RCA) of the oligonucleotide and incorporation of the red fluorescent probe. PLA analyses of EGFP–IP3R1 HeLa cells used combinations of antibodies (Ab) to VDAC1, KRAP or GFP (for EGFP–IP3R1). Maximum-intensity z-projections of confocal images show the PLA dots (red) and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Control images with only single antibodies are also shown. Results are typical of three to five independent PLA analyses. (B) Summary results show the average number of PLA dots per cell in a field that typically included ∼10 cells. Results show values for each field with mean±s.e.m. For each analysis, the number of cells, fields and independent experiments were: GFP and VDAC1 (512, 23, 4), KRAP and VDAC1 (983, 37, 6), KRAP only (559, 23, 3), GFP only (767, 26, 3) and VDAC1 only (738, 34, 4). *P<0.05; ****P<0.0001; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s correction. (C) Confocal section of PLA in EGFP–IP3R1 HeLa cells shows KRAP proximity to VDAC1 (PLA dots, magenta) and endogenously tagged IP3R1 (green). Enlargements of boxed areas show coincidence of EGFP–IP3R puncta with PLA spots. Manders' split coefficient, 0.82±0.15 (mean±s.d.); n=7 cells. (D) PLA analyses of the interactions between VDAC1 and EGFP–IP3R1 in EGFP–IP3R1 HeLa cells treated with NS siRNA or KRAP siRNA and after rescue with an siRNA-resistant KRAP expression plasmid. Maximum-intensity z-projections of confocal images show the PLA dots (red) and nuclei (DAPI, blue). (E) Summary results show the average number of PLA dots per cell in a field, with mean±s.e.m. For each treatment, the number of cells, fields and independent experiments were: NS siRNA (1116, 46, 7), KRAP siRNA (1003, 44, 7) and rescue (753, 51, 7). *P<0.05; repeated measures one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's test performed on the seven matched experiments. (F) IP3Rs at ER–mitochondrial membrane contact sites (ERMCSs) release Ca2+ that fuels the low-affinity mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake system (MCU). KRAP licenses these IP3Rs to release Ca2+ and it also stabilizes the ERMCS.

Next, we used PLA with EGFP–IP3R1 and VDAC1 to determine the effects of KRAP on the association of IP3Rs with mitochondria. siRNA-mediated knockdown of KRAP caused a significant reduction in the PLA signal. The association of IP3Rs with mitochondria was restored by the expression of siRNA-resistant KRAP (Fig. 5D,E). These results establish that KRAP contributes to maintaining the ERMCSs wherein IP3Rs and mitochondria interact to facilitate the delivery of Ca2+ from the ER to mitochondria (Fig. 5F).

DISCUSSION

We showed previously that IP3Rs must be licensed by their association with KRAP before they can respond to IP3 and evoke local or global cytosolic Ca2+ signals (Thillaiappan et al., 2021). Our present results extend these observations by demonstrating that KRAP is also required to license the IP3Rs that deliver Ca2+ to the surface of mitochondria within ERMCSs (Figs 1–3). KRAP is present at ERMCSs, a substantial fraction of mitochondria-associated IP3Rs (∼30%) colocalize with KRAP, and loss of KRAP abolishes the mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake that usually follows activation of IP3Rs (Figs 1–5). As the loss of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is not due to collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. S2) or deficient MCU (Fig. 3G,H), we suggest that regardless of whether IP3Rs deliver Ca2+ to the cytosol or within ERMCSs, their activity must be licensed by association with KRAP (Fig. 5F). Within both the cytosol and ERMCSs, only ∼30% of IP3Rs are associated with KRAP, suggesting that, in both locations, most IP3Rs are incapable of mediating Ca2+ release.

We note in passing that dissipating the mitochondrial membrane potential (with FCCP) or inhibition of MCU expression abolished IP3-evoked mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake, but there was no associated ‘overflow’ increase in [Ca2+]c (Fig. 1C–G). Similar results have been reported by others (Young et al., 2022), although, more commonly, inhibition of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake has been reported to exaggerate the IP3-evoked increase in [Ca2+]c (Drago et al., 2012; Fonteriz et al., 2016; Koval et al., 2019; Lombardi et al., 2019). The disparity probably reflects the differential distribution of licensed IP3Rs between ERMCSs and cytosol-disposed ER in different cells; only cells with many of their licensed IP3Rs within ERMCSs are likely to show detectable ‘overflow’ increases in [Ca2+]c when mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake is inhibited.

Our results identified an additional role for KRAP in facilitating Ca2+ transfer at ERMCSs, namely in maintaining the assembly of the ERMCSs wherein Ca2+ transfer from IP3Rs to mitochondria occurs. PLA analyses of KRAP with VDAC1 (in the OMM) showed that they were closely associated (within ∼40 nm of each other) at ERMCSs, and similar analyses with VDAC1 and IP3Rs established that their association was disrupted when KRAP expression was reduced (Fig. 5). The PLA analyses were restricted to endogenously tagged EGFP–IP3R1 because the GFP antibody is better than any available IP3R antibodies. However, our results are likely to be applicable to all three IP3R subtypes. First, within the HeLa cells used for PLA, the association of EGFP–IP3R1 with the other subtypes is consistent with their random assembly into tetramers (Thillaiappan et al., 2017). Second, recent work shows that all three IP3R subtypes contribute to Ca2+ transfer between the ER and mitochondria (Bartok et al., 2019; Katona et al., 2022). We have not therefore assessed whether KRAP differentially regulates IP3R subtypes at ERMCSs.

We suggest that KRAP is required for effective assembly or for maintaining the stability of ERMCSs wherein IP3R delivers Ca2+ to mitochondria (Fig. 5F). This observation aligns with a developing theme in Ca2+ signalling, namely that the Ca2+ channels responsible for delivering Ca2+ into MCSs might independently contribute to the structural stability of the MCSs. IP3Rs, for example, have been reported to contribute to the stability of ERMCSs (Bartok et al., 2019), and the endosomal Ca2+ channel TPC1 (also known as TPCN1) has been reported to stabilize the MCS between the ER and endosomes (Kilpatrick et al., 2017). Within ERMCSs, the structural contribution of IP3Rs to MCS stability occurred even with pore-dead Ca2+ channels (Bartok et al., 2019; Katona et al., 2022). Hence, the ∼70% of IP3Rs at ERMCSs that are not associated with KRAP and thus incapable of releasing Ca2+ might nevertheless contribute to assembling the ERMCSs. Our results develop this theme further by revealing that KRAP, a protein essential for IP3R activity, also contributes to the structural stability of ERMCSs. IP3Rs can move in and out of ERMCSs, but they must be immobilized to effectively transfer Ca2+ to mitochondria (Katona et al., 2022). Our results suggest that KRAP, in addition to its role in licensing IP3Rs beneath the PM (Thillaiappan et al., 2017, 2021), also immobilizes and licenses IP3Rs deeper within the cell at ERMCSs. We have not resolved whether the enhanced stability of ERMCSs by KRAP is mediated by immobilized IP3Rs or by other interactions between KRAP and the ER and/or mitochondrial proteins.

A protein related to KRAP, TESPA1 (thymocyte-expressed, positive selection-associated 1), which shares an IP3R-binding motif with KRAP, also interacts with IP3Rs at ERMCSs and regulates cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ signals (Matsuzaki et al., 2013). However, unlike the ubiquitously expressed KRAP (Fujimoto et al., 2007), TESPA1 is expressed predominantly in immune cells (Matsuzaki et al., 2012), such that a widespread regulation of ERMCSs by TESPA1 is unlikely.

We conclude that KRAP, originally identified because it is upregulated in colorectal cancer cell lines expressing mutant KRas (Inokuchi et al., 2004), fulfils a dual function in regulating Ca2+ transfer from the ER to mitochondria through IP3Rs. KRAP licenses IP3R within ERMCSs to respond to IP3, just as it does for IP3Rs that release Ca2+ to the cytosol (Thillaiappan et al., 2021). In addition, KRAP contributes to the structural stability of the ERMCSs wherein the Ca2+ transfer from the ER to mitochondria occurs. Remodelling of mitochondrial Ca2+ signalling is critical in shaping Ras-dependent oncogenic signalling cascades (Rimessi et al., 2015). Therefore, our findings also link the regulation of IP3R-mediated Ca2+ delivery at ERMCSs to Ras signalling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Calbryte 520 AM was from AAT Bioquest (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Histamine dihydrochloride, Triton X-100, FCCP, ECL western blotting detection reagents (Cytiva) and poly-L-lysine (0.1% w/v in H2O) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was from Europa Bio-Products (Ely, UK). Human fibronectin was from Merck Millipore (Watford, UK). CGP 37157 [7-chloro-5-(2-chlorophenyl)-1,5-dihydro-4,1-benzothiazepin-2(3H)-one] and ionomycin were from Cambridge Biosciences (Cambridge, UK). MitoTracker Deep Red FM, NuPAGE 4–12% Bis–Tris gels (NB0322BOX), iBlot 2 transfer stacks, polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) regular size membranes (IB24001), iBlot gel transfer system, PBS and the Neon transfection system were from Thermo Fisher Scientific. TransIT-LT1 reagent was from Geneflow (Lichfield, UK). Imaging dishes were from Cellvis (Gerasdorf bei Wein, Austria). Plasmids encoding the following proteins were used: TOM20 [translocase of outer (mitochondrial) membrane 20, also known as TOMM20] tagged to GFP (TOM20–GFP) (Prole and Taylor, 2019a), Mito-R-GECO1 (Addgene, #46021) (Wu et al., 2013), human KRAP with an N-terminal myc-DDK tag (OriGene, Rockville, MD, USA, #RC205550) and siRNA-resistant human KRAP with an N-terminal myc-DDK tag (Thillaiappan et al., 2021). The following antibodies were used for western blotting (WB), immunocytochemistry (IC), or PLAs: anti-KRAP (rabbit polyclonal; ProteinTech, Manchester, UK, #14157-1-AP, RRID:AB_2195472; WB 1:1000), ChromoTek GFP-Booster ATTO488 (nanobody; Chromotek, Planegg-Martinsried, Germany #gba488; RRID: AB_2631386; IC 1:500), anti-MCU (rabbit polyclonal; Thermo Fisher Scientific, PA5-109304, RRID:AB_2854715; WB 1:1000), anti-β-actin (mouse monoclonal; Cell Signaling Technology, Leiden, Netherlands, #8H10D10, RRID:AB_2242334; WB 1:20,000), IRDye 680RD goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (LI-COR, 926-68070, RRID:AB_10956588; WB 1:10,000), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Abcam, ab6795, RRID:AB_955446; WB 1:10,000), Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-11011, RRID:AB_143157; WB 1:10,000), Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-11008, RRID:AB_143165; WB 1:10,000), Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A-21235, RRID:AB_2535804; WB 1:10,000), anti-VDAC1 (Abcam, ab14734, RRID:AB_443084; PLA 1:400), anti-GFP (Abcam, ab290, RRID:AB_303395; PLA 1:200, WB 1:1000) and anti-TOM20 (Abcam, ab56783, RRID:AB_945896; WB 1:1000). The PLA kits used were Duolink in situ PLA probes (anti-rabbit PLUS and anti-mouse MINUS, affinity-purified donkey anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG, respectively), Duolink in situ detection reagents Red, mounting medium containing DAPI and wash buffer, from Sigma-Aldrich or NaveniFlex 100 MR (from Cambridge Biosciences). The siRNAs used were: Silencer siRNA against human KRAP (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #AM16708, assay ID, 143004), Silencer negative control no.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #AM4635) and ON-TARGETplusTM SMARTpool MCU siRNA (Dharmacon, L-015519-02-0005). All siRNA sequences are provided in Table S1. The Bradford protein assay kit (DC protein assay kit II, 5000112) and MOPS SDS Running Buffer 20× (NP001-02) were from Bio-Rad. Tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE)-mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit was from Abcam (ab113852). The sources of additional materials are provided in relevant sections of the Materials and Methods.

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa and edited HeLa cells, in which both copies of the endogenous genes encoding IP3R1 (ITPR1) were N-terminally tagged with monomeric EGFP (EGFP–IP3R1 HeLa cells) (Thillaiappan et al., 2017), were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM)/F-12 with GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #31331028) and 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich, #F7524, batch BCBX5042). The cells were maintained at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2 and passaged every 3–4 days with TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #12605010). Regular screening confirmed that all cells were mycoplasma free.

For imaging, cells were grown on 35-mm glass-bottomed dishes coated with human fibronectin (10 μg/ml). For transient transfections with protein-encoding plasmids, cells were transfected using TransIT-LT1 reagent (1.5 μg DNA per 3.75 μl reagent per dish) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were assayed after 24 h. Transfections with siRNA followed the manufacturer's instructions using a Neon transfection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Briefly, ∼100,000 cells were diluted in 100 μl of R buffer and incubated with siRNA (200 nM). Cells were electroporated using a 100-μl Neon pipette tip (pulse voltage 1005 V; pulse width, 35 ms; two pulses) and transferred into complete growth medium. Electroporated cells were distributed into fibronectin-coated 35-mm imaging dishes (∼50,000 cells/dish) for microscopy or into 25-cm2 culture flasks (∼100,000 cells) for protein analyses. Cells were assayed after 72 h. For rescue experiments, cells were first electroporated with siRNA (200 nM), and after 48 h, they were transfected with an siRNA-resistant KRAP plasmid (4.5 μg) using TransIT-LT1 reagent. Cells were used after a further 24 h.

Western blotting

Cells in 25-cm2 culture flasks were harvested by centrifugation (650 g, 2 min, 22°C), washed with ice-cold PBS (1.06 mM KH2PO4, 155 mM NaCl, 3 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.3, 20°C), and the pellet was resuspended (0.1 ml) in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA; 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0) containing protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich, #11873580001; 1 mini-tablet per 10 ml). After sonication on ice (Transsonic, T420; three 10 s sonication pulses and three 10 s pauses), samples were incubated with rotation (30 min, 4°C) and centrifuged (14,000 g, 15 min, 4°C), and the supernatant was used for analysis. Proteins were quantified using the DC protein assay kit II with BSA in RIPA buffer as the standard. For western blotting, proteins were separated on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels, run at 160 V for 45 min in MOPS SDS running buffer, and transferred to a PVDF membrane using an iBlot 2 gel-transfer system. The membrane was blocked (1 h with shaking) in TBS (137 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.6) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) with 5% BSA, washed twice with TBST, incubated in TBST containing 1% BSA (16 h, 4°C with shaking) with the primary antibody, washed with TBST (five times for 5 min), incubated with secondary antibody in TBST containing 1% BSA (1 h, 20°C with shaking), and washed with TBST (five times for 5 min). Bands were quantified using an iBright FL1500 imaging system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) either directly for the fluorescent secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 568) or by chemiluminescence after treatment with ECL Prime western blotting detection reagent (for HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies; see Materials). We confirmed that, within the range of loadings used for analysis, protein band intensities scaled linearly with the amount of protein loaded.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells grown on fibronectin-coated 35-mm glass-bottomed dishes were washed three times with HBS (20°C) and then incubated with MitoTracker Deep Red (500 nM, 30 min, 37°C). HBS had the following composition: 135 mM NaCl, 5.9 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 11.5 mM d-glucose, 11.6 mM HEPES, pH 7.3. Cells were washed three times with HBS, fixed with methanol (20 min, −20°C), washed three times with PBS, and permeabilized using 0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS (5 min, 20°C). After three washes with PBS, cells were incubated in PBS containing 5% BSA (1 h, 20°C), washed in the same medium, then incubated (12 h, 4°C) with ChromoTek GFP-Booster ATTO488 and the primary antibody to KRAP in PBS containing 3% BSA. Cells were then washed three times with PBS, incubated in the dark with the secondary antibody in PBS with 3% BSA (1 h, 20°C), and washed three times with PBS before imaging. Dilutions of the antibodies used are provided in the Materials section.

Proximity ligation assays

A Duolink PLA was used to determine protein interactions at ERMCSs. PLA reports the presence of juxtaposed proteins when secondary antibodies conjugated to complementary oligonucleotides come sufficiently close (∼40 nm) to hybridize and allow rolling-circle amplification, which is then detected with a fluorescent probe (Texas Red) (Tubbs and Rieusset, 2016) (Fig. 5A). Cells grown on fibronectin-coated 35-mm glass-bottomed dishes were fixed in PBS with 4% paraformaldehyde (30 min, 20°C), washed with PBS, permeabilized (0.25% Triton X-100 in PBS, 5 min, 20°C) and incubated with primary antibodies (16 h, 4°C). All subsequent steps, including incubation with the oligonucleotide-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit PLUS and anti-mouse MINUS), were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The antibodies and their dilutions are described in the Materials section. PLA products were visualized using an Olympus microscope equipped with a 60× objective, and the number of spots per cell were quantified using ImageJ. PLA analysis of interactions between EGFP–IP3R and VDAC1 or KRAP and VDAC1 used Duolink PLA reagents (Fig. 5A,B). Supply difficulties necessitated the use of a different PLA kit (NaveniFlex) for analyses of KRAP knockdown (Fig. 5D,E). Indistinguishable results were obtained when the two kits were applied to analyses of the interactions between IP3R on the ER and VDAC1 on the mitochondria.

Fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy used an Olympus (Ca2+ imaging, colocalization of Mito-R-GECO and PLA analysis) or Zeiss (three-colour imaging of IP3R, KRAP and mitochondria) microscope. The inverted Olympus IX83 microscope was equipped with 60× (numerical aperture or NA, 1.45) and 100× oil-immersion objectives (NA, 1.49), a multi-line laser bank (488 and 561 nm) and an iLas2 targeted laser illumination system (Cairn, Faversham, UK). The excitation light passed through a quad dichroic beam-splitter (TRF89902-QUAD). The emitted light passed through appropriate filters (Cairn Optospin; peak/bandwidth (nm): 525/50 and 630/75) and was detected with an iXon Ultra 897 electron multiplied charge-coupled device (EMCCD) camera (512×512 pixels, Andor, Belfast, Northern Ireland). The Zeiss LSM700 upright confocal microscope, on which imaging dishes were viewed in an inverted position, was equipped with a 63× oil-immersion objective (NA, 1.4) and four excitation solid-state laser lines (405, 488, 555 and 639 nm). The emitted light was detected by two photomultiplier tubes in the scanhead using a shared pinhole and a sliding dichroic filter to separate the emitted wavelengths. We confirmed that for all multi-colour imaging, there was no bleed-through between channels.

Measurement of cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ concentrations in single cells

We sought cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ indicators with compatible spectra and with changes in fluorescence amplitude after stimulation with a maximally effective concentration of histamine (100 μM) that were usually less than 50% of the maximal fluorescence signal (Fmax). Fmax signals were determined after addition of CGP 37157 (50 µM) to inhibit the mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (Suzuki et al., 2014) and then, after 1 min, addition of ionomycin (10 μM) in HBS containing a final Ca2+ concentration of 20 mM. With these conditions satisfied (i.e. the fluorescence signal F usually less than 50% of Fmax), it is reasonable to assume that changes in the fluorescence intensity of the Ca2+ indicators are approximately linearly related to changes in [Ca2+]. After investigating several cytosolic (Fluo 8 AM, Cal 520 AM and Calbryte 520 AM) and mitochondrial Ca2+ indicators (Fura 2 AM, MtCEPIA 2, Mito-LAR-GECO1.2 and Mito-R-GECO1), we selected Calbryte 520 (equilibrium dissociation constant for Ca2+,  =1200 nM) and Mito-R-GECO1 (

=1200 nM) and Mito-R-GECO1 ( = 480 nM) (Wu et al., 2013) to measure [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m, respectively.

= 480 nM) (Wu et al., 2013) to measure [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m, respectively.

HeLa cells grown on fibronectin-coated 35-mm glass-bottomed dishes were transfected with Mito-R-GECO1 and then loaded with Calbryte 520 by incubation with Calbryte 520 AM (2 μM, 1 h, 20°C) in HBS supplemented with 0.02% Pluronic F-127 (Sigma-Aldrich, #P2443). Cells were then washed and incubated in HBS for 30 min, and, immediately before imaging, the HBS was replaced with Ca2+-free HBS (HBS with no added CaCl2). Imaging at 20°C used an Olympus IX83 microscope with a 100× objective and switches between pairs of excitation (λex) and emission (λem) wavelengths: Calbryte 520 (λex=488 nm, λem=525 nm) and Mito-R-GECO1 (λex=561 nm, λem=630 nm). Images were acquired at 1-s intervals for each indicator, corrected for background fluorescence, and analyzed using MetaMorph Microscopy Automation and Image Analysis software (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). A region of interest was drawn around each cell successfully transfected with Mito-R-GECO1 and responses for both cytosolic and mitochondrial Ca2+ indicators were reported as F/Fmax. We confirmed that under the conditions used for recording [Ca2+]c and [Ca2+]m, there was no bleed-through between the two channels (Fig. S1).

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

HeLa cells treated with NS siRNA or siRNA against KRAP were grown on poly-L-lysine-coated (0.01% w/v) 35-mm imaging dishes. Mitochondrial membrane potential was measured using a TMRE assay following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were incubated with TMRE (100 nM, 15 min) and DAPI at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2. Where indicated, cells were incubated with FCCP (20 µM, 10 min) to dissipate the mitochondrial membrane potential before addition of TMRE. Cells were then washed twice with PBS, and fluorescence intensity was measured from single cells at 20°C in PBS using an EVOS M7000 cell imaging system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a 60× oil-immersion objective (NA, 1.45). Cells were kept in the dark during all manipulations.

Quantification of fluorescence images

Fluorescence images were corrected for background by subtraction of fluorescence collected from a region outside the cell using MetaMorph software. Capture and processing of widefield images and confocal PLA images was performed using MetaMorph. Confocal images of IP3R, KRAP and mitochondrial fluorescence were captured using Zen imaging software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Germany).

Colocalization analysis within widefield images (Mito-R-GECO1 and TOM20–GFP) used the JACoP plugin (Bolte and Cordelieres, 2006) in Fiji/ImageJ (Schindelin et al., 2012) to calculate the Manders' coefficients that report the fraction of Mito-R-GECO1 colocalized with TOM20–GFP. For colocalization analyses of confocal images, images were first deconvolved using SVI HuygensPro software (Scientific Volume Imaging B.V., VB Hilversum, the Netherlands) and then background corrected using MetaMorph. Colocalization used an object-based program within ImageJ (DiAna) (Gilles et al., 2017), wherein the centre-to-centre distances between each EGFP–IP3R punctum and the nearest KRAP punctum were assessed following a spot segmentation of each image. For analysis of three-colour colocalization (IP3Rs, KRAP and mitochondria), a mask of the regions containing mitochondria was generated, EGFP–IP3R puncta within these regions were identified and the centre-to-centre distances from these IP3R puncta to the nearest KRAP punctum were assessed using DiAna. We considered IP3R and KRAP puncta to be colocalized if their centre-to-centre distance was <233 nm (3 pixels), which is close to the theoretical lateral resolution of the confocal microscope.

PLA spots were quantified according to previously described methods (López-Cano et al., 2019). Briefly, following background subtraction, maximum z-projected images were converted into binary images. The number of PLA spots and cells in a field identified by DAPI staining were counted using the Analyze Particles function on ImageJ.

Statistical analysis

Most results are presented as mean±s.d. or s.e.m. from n independent analyses. Statistical analyses used either two-tailed paired or unpaired Student's t-test (two variables) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test (more than two variables); P<0.05 was considered significant (PRISM, version 9, GraphPad, USA). For colocalization analyses using DiAna, the distribution of KRAP puncta was shuffled 100 times within each cell and the distances from each KRAP punctum to the nearest IP3R punctum was reassessed. We considered the observed distances to be statistically significant if they fell outside the 95% confidence interval of the randomized distances.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Graham Ladds for his support during the latter stages of this work.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conceptualization: P.A.-A., C.W.T.; Methodology: P.A.-A.; Formal analysis: P.A.-A., A.I., K.K.; Investigation: P.A.-A., A.I., K.K.; Writing - original draft: P.A.-A.; Writing - review & editing: P.A.-A., A.I., C.W.T.; Supervision: C.W.T.; Funding acquisition: C.W.T.

Funding

This work was supported by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council grant (BB/TO/12986/1) to C.W.T. (then held by Graham Ladds, Cambridge) and a Senior Investigator Award to C.W.T. from Wellcome. P.A-A. is an Alan Wilson Research Fellow at Emmanuel College, Cambridge. A.I. was supported by a PhD studentship from the Cambridge Trust. Open Access funding provided by University of Cambridge. Deposited in PMC for immediate release.

Data availability

All relevant data can be found within the article and its supplementary information.

References

- Area-Gomez, E., de Groof, A. J., Boldogh, I., Bird, T. D., Gibson, G. E., Koehler, C. M., Yu, W. H., Duff, K. E., Yaffe, M. P., Pon, L. A.et al. (2009). Presenilins are enriched in endoplasmic reticulum membranes associated with mitochondria. Am. J. Pathol. 175, 1810-1816. 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atakpa, P., Thillaiappan, N. B., Mataragka, S., Prole, D. L. and Taylor, C. W. (2018). IP3 receptors preferentially associate with ER-lysosome contact sites and selectively deliver Ca2+ to lysosomes. Cell Reports 25, 3180-3193. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.11.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartok, A., Weaver, D., Golenar, T., Nichtova, Z., Katona, M., Bansaghi, S., Alzayady, K. J., Thomas, V. K., Ando, H., Mikoshiba, K.et al. (2019). IP3 receptor isoforms differently regulate ER-mitochondrial contacts and local calcium transfer. Nat. Commun. 10, 3726. 10.1038/s41467-019-11646-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolte, S. and Cordelieres, F. P. (2006). A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J. Microsc. 224, 213-232. 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01706.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefani, D., Raffaello, A., Teardo, E., Szabo, I. and Rizzuto, R. (2011). A forty-kilodalton protein of the inner membrane is the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 476, 336-340. 10.1038/nature10230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefani, D., Bononi, A., Romagnoli, A., Messina, A., De Pinto, V., Pinton, P. and Rizzuto, R. (2012). VDAC1 selectively transfers apoptotic Ca2+ signals to mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 19, 267-273. 10.1038/cdd.2011.92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drago, I., De Stefani, D., Rizzuto, R. and Pozzan, T. (2012). Mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake contributes to buffering cytoplasmic Ca2+ peaks in cardiomyocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 12986-12991. 10.1073/pnas.1210718109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonteriz, R., Matesanz-Isabel, J., Arias-Del-Val, J., Alvarez-Illera, P., Montero, M. and Alvarez, J. (2016). Modulation of calcium entry by mitochondria. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 898, 405-421. 10.1007/978-3-319-26974-0_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foskett, J. K., White, C., Cheung, K. H. and Mak, D. O. (2007). Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol. Rev. 87, 593-658. 10.1152/physrev.00035.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, T. and Shirasawa, S. (2011). KRAS-induced actin-interacting protein: a potent target for obesity, diabetes and cancer. Anticancer Res. 31, 2413-2417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, T., Koyanagi, M., Baba, I., Nakabayashi, K., Kato, N., Sasazuki, T. and Shirasawa, S. (2007). Analysis of KRAP expression and localization, and genes regulated by KRAP in a human colon cancer cell line. J. Hum. Genet. 52, 978-984. 10.1007/s10038-007-0204-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, T., Machida, T., Tanaka, Y., Tsunoda, T., Doi, K., Ota, T., Okamura, T., Kuroki, M. and Shirasawa, S. (2011a). KRAS-induced actin-interacting protein is required for the proper localization of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in the epithelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 407, 438-443. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, T., Machida, T., Tsunoda, T., Doi, K., Ota, T., Kuroki, M. and Shirasawa, S. (2011b). Determination of the critical region of KRAS-induced actin-interacting protein for the interaction with inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 408, 282-286. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, T., Machida, T., Tsunoda, T., Doi, K., Ota, T., Kuroki, M. and Shirasawa, S. (2011c). KRAS-induced actin-interacting protein regulates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-receptor-mediated calcium release. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 408, 214-217. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.03.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles, J. F., Dos Santos, M., Boudier, T., Bolte, S. and Heck, N. (2017). DiAna, an ImageJ tool for object-based 3D co-localization and distance analysis. Methods 115, 55-64. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gincel, D., Zaid, H. and Shoshan-Barmatz, V. (2001). Calcium binding and translocation by the voltage-dependent anion channel: a possible regulatory mechanism in mitochondrial function. Biochem. J. 358, 147-155. 10.1042/bj3580147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helle, S. C., Kanfer, G., Kolar, K., Lang, A., Michel, A. H. and Kornmann, B. (2013). Organization and function of membrane contact sites. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1833, 2526-2541. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung, V., Lam, S. S., Udeshi, N. D., Svinkina, T., Guzman, G., Mootha, V. K., Carr, S. A. and Ting, A. Y. (2017). Proteomic mapping of cytosol-facing outer mitochondrial and ER membranes in living human cells by proximity biotinylation. eLife 6, e24463. 10.7554/eLife.24463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inokuchi, J., Komiya, M., Baba, I., Naito, S., Sasazuki, T. and Shirasawa, S. (2004). Deregulated expression of KRAP, a novel gene encoding actin-interacting protein, in human colon cancer cells. J. Hum. Genet. 49, 46-52. 10.1007/s10038-003-0106-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhak, D. N., Tyanova, S., Cox, J. and Borner, G. H. (2016). Global, quantitative and dynamic mapping of protein subcellular localization. Elife 5, e16950. 10.7554/eLife.16950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona, M., Bartók, Á., Nichtova, Z., Csordás, G., Berezhnaya, E., Weaver, D., Ghosh, A., Várnai, P., Yule, D. I. and Hajnóczky, G. (2022). Capture at the ER-mitochondrial contacts licenses IP3 receptors to stimulate local Ca2+ transfer and oxidative metabolism. Nat. Commun. 13, 6779. 10.1038/s41467-022-34365-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, B. S., Eden, E. R., Hockey, L. N., Yates, E., Futter, C. E. and Patel, S. (2017). An endosomal NAADP-sensitive two-pore Ca2+ channel regulates ER-endosome membrane contact sites to control growth factor signaling. Cell Rep. 18, 1636-1645. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.01.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., Moody, J. P., Edgerly, C. K., Bordiuk, O. L., Cormier, K., Smith, K., Beal, M. F. and Ferrante, R. J. (2010). Mitochondrial loss, dysfunction and altered dynamics in Huntington's disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 3919-3935. 10.1093/hmg/ddq306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirichok, Y., Krapavinsky, G. and Clapham, D. E. (2004). The mitochondrial calcium uniporter is a highly selective ion channel. Nature 427, 360-364. 10.1038/nature02246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koval, O. M., Nguyen, E. K., Santhana, V., Fidler, T. P., Sebag, S. C., Rasmussen, T. P., Mittauer, D. J., Strack, S., Goswami, P. C., Abel, E. D.et al. (2019). Loss of MCU prevents mitochondrial fusion in G1-S phase and blocks cell cycle progression and proliferation. Sci. Signal. 12, eaav1439. 10.1126/scisignal.aav1439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, A. A., Gibb, A. A., Arif, E., Kolmetzky, D. W., Tomar, D., Luongo, T. S., Jadiya, P., Murray, E. K., Lorkiewicz, P. K., Hajnóczky, G.et al. (2019). Mitochondrial calcium exchange links metabolism with the epigenome to control cellular differentiation. Nat. Commun. 10, 4509. 10.1038/s41467-019-12103-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Cano, M., Fernández-Dueñas, V. and Ciruela, F. (2019). Proximity ligation assay image analysis protocol: addressing receptor-receptor interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 2040, 41-50. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9686-5_3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki, H., Fujimoto, T., Ota, T., Ogawa, M., Tsunoda, T., Doi, K., Hamabashiri, M., Tanaka, M. and Shirasawa, S. (2012). Tespa1 is a novel inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor binding protein in T and B lymphocytes. FEBS Open Biol. 2, 255-259. 10.1016/j.fob.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki, H., Fujimoto, T., Tanaka, M. and Shirasawa, S. (2013). Tespa1 is a novel component of mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes and affects mitochondrial calcium flux. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 433, 322-326. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.02.099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, C. C., Gomes, D. A., Thompson, M., Souto, N. C., Goes, T. S., Goes, A. M., Rodrigues, M. A., Gomez, M. V., Nathanson, M. H. and Leite, M. F. (2005). The type III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor preferentially transmits apoptotic Ca2+ signals into mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 40892-40900. 10.1074/jbc.M506623200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milakovic, T., Quintanilla, R. A. and Johnson, G. V. (2006). Mutant huntingtin expression induces mitochondrial calcium handling defects in clonal striatal cells: functional consequences. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 34785-34795. 10.1074/jbc.M603845200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prole, D. L. and Taylor, C. W. (2019a). A genetically-encoded toolkit of functionalized nanobodies against fluorescent proteins for visualizing and manipulating intracellular signalling. BMC Biol. 17, 41. 10.1186/s12915-019-0662-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prole, D. L. and Taylor, C. W. (2019b). Structure and function of IP3 receptors. Cold Spring Harb. Persp. Biol. 11, a035063. 10.1101/cshperspect.a035063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapizzi, E., Pinton, P., Szabadkai, G., Wieckowski, M. R., Vandecasteele, G., Baird, G., Tuft, R. A., Fogarty, K. E. and Rizzuto, R. (2002). Recombinant expression of the voltage-dependent anion channel enhances the transfer of Ca2+ microdomains to mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 159, 613-624. 10.1083/jcb.200205091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimessi, A., Patergnani, S., Bonora, M., Wieckowski, M. R. and Pinton, P. (2015). Mitochondrial Ca2+ remodeling is a prime factor in oncogenic behavior. Front. Oncol. 5, 143. 10.3389/fonc.2015.00143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roest, G., La Rovere, R. M., Bultynck, G. and Parys, J. B. (2017). IP3 receptor properties and function at membrane contact sites. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 981, 149-178. 10.1007/978-3-319-55858-5_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, A. A. and Voeltz, G. K. (2012). Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contacts: function of the junction. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 607-625. 10.1038/nrm3440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin, J., Arganda-Carreras, I., Frise, E., Kaynig, V., Longair, M., Pietzsch, T., Preibisch, S., Rueden, C., Saalfeld, S., Schmid, B.et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676-682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoes, I. C. M., Morciano, G., Lebiedzinska-Arciszewska, M., Aguiari, G., Pinton, P., Potes, Y. and Wieckowski, M. R. (2020). The mystery of mitochondria-ER contact sites in physiology and pathology: A cancer perspective. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1866, 165834. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, J., Kanemaru, K., Ishii, K., Ohkura, M., Okubo, Y. and Iino, M. (2014). Imaging intraorganellar Ca2+ at subcellular resolution using CEPIA. Nat. Commun. 5, 4153. 10.1038/ncomms5153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thillaiappan, N. B., Chavda, A. P., Tovey, S. C., Prole, D. L. and Taylor, C. W. (2017). Ca2+ signals initiate at immobile IP3 receptors adjacent to ER-plasma membrane junctions. Nat. Commun. 8, 1505. 10.1038/s41467-017-01644-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thillaiappan, N. B., Smith, H. A., Atakpa-Adaji, P. and Taylor, C. W. (2021). KRAP tethers IP3 receptors to actin and licenses them to evoke cytosolic Ca2+ signals. Nat. Commun. 12, 4514. 10.1038/s41467-021-24739-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubbs, E. and Rieusset, J. (2016). Study of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria interactions by in situ proximity ligation assay in fixed cells. J. Vis. Expts. 118, 54899. 10.3791/54899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tubbs, E. and Rieusset, J. (2017). Metabolic signaling functions of ER-mitochondria contact sites: role in metabolic diseases. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 58, R87-R106. 10.1530/JME-16-0189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecellio Reane, D., Rizzuto, R. and Raffaello, A. (2020). The ER-mitochondria tether at the hub of Ca2+ signaling. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 17, 261-268. 10.1016/j.cophys.2020.08.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vorontsova, I., Lock, J. T. and Parker, I. (2022). KRAP is required for diffuse and punctate IP3-mediated Ca2+ liberation and determines the number of functional IP3R channels within clusters. Cell Calcium. 107, 102638. 10.1016/j.ceca.2022.102638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J., Liu, L., Matsuda, T., Zhao, Y., Rebane, A., Drobizhev, M., Chang, Y. F., Araki, S., Arai, Y., March, K.et al. (2013). Improved orange and red Ca²+ indicators and photophysical considerations for optogenetic applications. ACS. Chem. Neurosci. 4, 963-972. 10.1021/cn400012b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, M. P., Schug, Z. T., Booth, D. M., Yule, D. I., Mikoshiba, K., Hajnόczky, G. and Joseph, S. K. (2022). Metabolic adaptation to the chronic loss of Ca2+ signaling induced by KO of IP3 receptors or the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter. J. Biol. Chem. 298, 101436. 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, W., Jin, H. and Huang, Y. (2021). Mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs): a potential therapeutic target for treating Alzheimer's disease. Clin. Sci. 135, 109-126. 10.1042/CS20200844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.