Abstract

The RU5 region at the 5′ RNA terminus of spleen necrosis virus (SNV) has been shown to facilitate expression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV) unspliced RNA independently of the Rev-responsive element (RRE) and Rev. The SNV sequences act as a distinct posttranscriptional control element to stimulate gag RNA nuclear export and association with polyribosomes. Here we sought to determine whether RU5 functions to neutralize the cis-acting inhibitory sequences (INSs) in HIV RNA that confer RRE/Rev dependence or functions as an independent stimulatory sequence. Experiments with HIV gag reporter plasmids that contain inactivated INS-1 indicated that neutralization of INSs does not account for RU5 function. Results with luciferase reporter gene (luc) plasmids further indicated that RU5 stimulates expression of a nonretroviral RNA that lacks INSs. Northern blot and RT-PCR analyses indicated that RU5 does not increase the steady-state levels or nuclear export of the luc transcript but rather that the U5 region facilitates efficient polyribosomal association of the mRNA. RU5 does not function as an internal ribosome entry site in bicistronic reporter plasmids, and it requires the 5′-proximal position for efficient function. Our results indicate that RU5 contains stimulatory sequences that function in a 5′-proximal position to enhance initiation of translation of a nonretroviral reporter gene RNA. We speculate that RU5 evolved to overcome the translation-inhibitory effect of the highly structured encapsidation signal and other replication motifs in the 5′ untranslated region of the retroviral RNA.

Highly structured 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs) are known to inhibit ribosome scanning and prevent efficient translation of a variety of mRNAs (11, 14, 16, 22, 23, 29–31, 35, 42, 43). The 5′ UTR of the retroviral primary unspliced transcript contains highly structured motifs that direct viral packaging of RNA into infectious virus and other steps in retroviral replication (44). In vitro translation assays with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV) RNA have verified that the HIV 5′ UTR inhibits efficient translation (11, 30). Efficient posttranscriptional control of HIV gene expression is regulated by the interaction of viral regulatory protein Rev and the Rev-responsive element (RRE) within incompletely spliced HIV transcripts (5, 8, 24). Rev is essential for the stability and nuclear export of RRE-containing transcripts (9, 10, 15, 27, 28) and activates their translational efficiency (1, 5, 8, 24). Some genetically simpler retroviruses utilize an RRE-like constitutive transport element that interacts with cellular Rev-like proteins to modulate cytoplasmic accumulation of the primary unspliced viral transcript (4, 32, 33). However, an analogous RRE/Rev-like RNA-protein interaction that facilitates translation for simple retroviruses has not been characterized.

Recent experiments have shown that the 5′ long terminal repeat (LTR) of spleen necrosis virus (SNV) can facilitate RRE/Rev-independent expression of HIV gag reporter gene RNA over 20,000-fold (5). Comparison of HIV gag reporter plasmids that contain the SNV LTR with those that contain the cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter (CMV IE) indicates that the SNV LTR increases cytoplasmic accumulation and polyribosomal localization of gag mRNA 2- to 3-fold and yields a 20,000-fold or greater increase in Gag protein production. Further analysis of the SNV LTR sequences revealed that the RU5 region of the SNV LTR is sufficient to facilitate RRE/Rev-independent Gag production from the CMV IE reporter plasmid. Parallel control experiments with RRE-containing HIV gag reporter gene plasmids indicated that Rev/RRE interaction increases gag RNA export and polyribosomal localization 3-fold coincident with an even more dramatic 300,000-fold increase in Gag protein production. A possible explanation for the positive effect of SNV sequences is that RU5 functions in a manner similar to Rev/RRE to neutralize cis-acting inhibitory sequences (INSs) in gag RNA that contribute to the low steady-state level of viral mRNAs in the absence of Rev (6, 26, 37, 39). An alternative possibility that is consistent with the apparent increase in translational efficiency is that RU5 functions independently of HIV INSs and is a 5′-proximal translation-regulatory element. For example, the iron response element is a conserved RNA stem-loop that confers potent iron-responsive translational regulation when positioned near the 5′ RNA terminus of a reporter transcript (2, 13, 16). RU5 may similarly utilize the 5′-proximal position to modulate the translational efficiency of mRNA.

We used a series of HIV gag and firefly luciferase gene (luc) reporter plasmids to investigate whether SNV sequences neutralize HIV INSs or function independently of INSs to stimulate expression of nonretroviral reporter mRNA. Our results demonstrate that RU5 is a stimulatory sequence that functions independently of HIV INSs to enhance translational initiation of luc mRNA. RU5 does not function as an internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) and requires the 5′-proximal position for efficient function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

The gag sequence of p37M1-4 (a kind gift of B. K. Felber, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, Md.) (38), which contains inactivated INS-1, was introduced into pYW100 (5) to create pSNVRU5gag (INS negative). The derivative contains a mutated SphI site that was introduced by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis.

SNV-luc plasmids were derived from previously described plasmids pYW207, pYW100, pYW204, pYW205, and pYW208 (5) by replacement of gag-pol sequences with luc at BglII and XbaI sites to create pCMVluc, pSNVRU5luc, pSNVRluc, pSNVluc, and pCMVRU5luc, respectively. The luc gene was amplified from pGL3 (Promega, Madison, Wis.) by PCR. To create pCMVasRU5luc (which contains RU5 in the antisense orientation), a XhoI site was introduced into pYW207 (5) by site-directed mutagenesis. Intermediate plasmid pTR119 was digested with XhoI and XbaI, and the gag-pol sequences were replaced with luc on a XhoI-XbaI PCR product.

All IRES plasmids used here are derivatives of pRL-CMV Renilla (Promega). The luc gene was excised from pGL3-promoter (Promega) and ligated adjacent to the encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) IRES in pCITE-1 (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) at NcoI and XbaI sites, yielding pTR250. The IRES-luc fragment was excised from pTR250 and ligated at the XbaI site of pRL-CMV in the sense and antisense orientations to create pRENIRESluc and pRENlucIRES, respectively. RU5-luc was amplified by PCR on template pSNVRU5luc with primers containing XbaI sites and ligated at the XbaI site of pRL-CMV in the sense and antisense orientations to create pRENRU5luc and pRENlucRU5, respectively. To construct pRENluc and plucREN, the luc gene was ligated at the XbaI site of pRL-CMV in the sense and antisense orientations, respectively.

To create pSV40RU5luc, a HindIII-digested PCR product containing SNV RU5 was ligated at the unique HindIII site in pGL3-promoter (which contains the simian virus 40 SV40 promoter). To create pSV40RU52luc, the 5′ HindIII site in pSV40RU5luc was destroyed by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis and the HindIII-digested PCR product was ligated at the unique 3′ HindIII site. The identities of all plasmids were verified by restriction digestion and sequence analysis. All luc plasmids contain identical 5′ UTRs from pGL3.

DNA transfection and analysis of protein production.

Reporter gene assays were performed with cultures of 293 cells transfected by a CaCl2 protocol (5) in three replicate 100- or 33-mm-diameter plates. The cells were harvested 48 h later in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 3 min, and resuspended in 0.1 or 0.05 ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40). Gag levels were quantified by a Gag enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Coulter Corp., Miami, Fla.) and normalized to Luc activity (in relative light units [RLU]); Luc was expressed from cotransfected pGL3. Luc assays were performed with 20 μl of lysate and 100 μl of Luciferase Assay Reagent (Promega) and quantified in a Lumicount luminometer (Packard, Meriden, Conn.). Dual measurement of the luciferases expressed from the firefly (Photinus pyralis) luc and sea pansy (Renilla reniformis) ren genes was performed by using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

RNA preparation and analysis.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic RNAs were prepared, as previously described (5), by a gentle lysis of cells and isolation by the Tri Reagent protocol (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, Ohio). Reverse transcription was performed in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 20 ng of RNA and 1 μl of Sensiscript reverse transcriptase (RT) (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.) in a buffer provided by the manufacturer and with antisense primers that are complementary to luc and the actin gene. The actin gene primers will amplify across intronic sequences and are useful to distinguish spliced (289 nucleotides [nt]) and unspliced (400 nt) actin RNA. Two microliters of each cDNA was used in a reaction mixture with 2.5 U of Taq polymerase and subjected to 25 cycles of PCR (94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s). The linear range of the RT-PCR was determined by titrating the input RNA and varying the number of PCR cycles, and the assays were performed within the linear range.

Northern blot analyses were performed with 1 μg of total nuclear or cytoplasmic RNA. Samples were separated on 1.2% agarose gels containing 5% formaldehyde, transferred to Duralon-UV membranes (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), and incubated with either luc or cyclophilin gene (cyp) DNA probes. The probes were prepared by using a random-primer DNA-labeling system (Gibco-BRL) with gel-purified luc or cyp PCR products and [α-32P]dCTP. The membranes were visualized by PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) analysis and quantified by using ImageQuaNT version 4.2 software (Molecular Dynamics).

For ribosomal RNA profile analysis, 107 293 cells in a 125-cm2 flask were transfected and harvested 48 h later in PBS, incubated with a 100-μg/ml cyclohexamide solution for 20 min, washed twice in PBS, and divided into two fractions. Cells in each fraction were gently lysed on ice with 500 μl of chilled Mg buffer (10 mM HEPES, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM CaCl2, 7 mM MgCl2, 0.5% NP-40) containing 1 mM dithiothreitol and 100 U of RNasin (Promega)/ml. Cell lysates were centrifuged for 2 min at 14,000 × g, and 50 mM EDTA (pH 8) or equivalent Mg buffer was added to the cytoplasmic supernatant. The samples were then layered onto a 10-ml linear gradient of 15 to 45% sucrose in 10 mM HEPES containing 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM CaCl2, 7 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM dithiothreitol and centrifuged at 35,000 × g and 4°C for 2.25 h in a Beckman SW41 rotor. Gradients were fractionated, and the A254 was monitored using an ISCO (Lincoln, Nebr.) fractionation system. Each fraction was treated with DNase (Gibco-BRL, Rockville, Md.) and then extracted with phenol twice, and the RNA was precipitated with ethanol. RT-PCR with gag-specific primers was performed on 20 ng of RNA with Sensiscript RT, and reactions without RT were used to verify lack of DNA contamination. The amplification products were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis and quantified by Alpha Imager (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, Calif.) analysis. For Northern blot analyses, the entire RNA sample from each fraction was used and the membranes were probed as described above.

RESULTS

SNV RU5 contains stimulatory sequences.

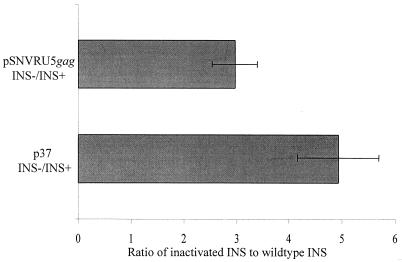

cis-acting INSs in HIV mRNA act as nuclear retention signals to dominantly repress the cytoplasmic accumulation of incompletely spliced HIV transcripts (6, 26, 37–39). The inhibitory effect of INSs is derepressed by interaction of RRE and Rev, and mutational inactivation of INSs neutralizes the RRE/Rev dependence of the HIV RNA (37, 38). If SNV sequences and putative host proteins derepress INSs in a manner analogous to RRE/Rev, mutational inactivation of INS would not augment Gag production from the SNVRU5gag reporter plasmid. Conversely, if SNV sequences function independently of INSs, inactivation of the INSs would augment Gag expression. Transfected 293 cells were evaluated for Gag production from reporter gene plasmids that encode either wild-type gag or gag with a previously characterized INS-1 inactivation from gag reporter plasmid p37M1-4 (38). Gag ELISA results from three triplicate experiments indicated that Gag protein levels were augmented in response to INS-1 inactivation and are consistent with an INS-independent phenotype (Fig. 1). pSNVRU5luc exhibited a threefold increase in response to INS-1 inactivation, and the control gag reporter plasmids p37 and p37M1-4 (38) yielded comparable (fivefold) increases.

FIG. 1.

Effect of INS-1 inactivation on Gag reporter gene production. Triplicate cultures of 293 cells were cotransfected with pSNVRU5gag containing or lacking the INS-1 mutation (1.5 μg) and the luc-containing transfection control plasmid pGL3 (0.5 μg). HIV LTR-based plasmids p37 (INS+) and p37M1-4 (INS−) (0.1 μg) were cotransfected with pGL3 (0.5 μg) and HIV Tat expression plasmid pSV2tat (0.01 μg). Cell lysates were analyzed for Gag by ELISA and for transfection efficiency by Luc assay. Data are presented as the ratio of Gag production from plasmids containing the INS-1 mutation to that from plasmids lacking the mutation (wild type).

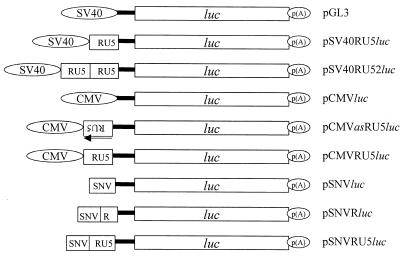

RU5 stimulation of a nonretroviral reporter gene that lacks INSs would provide further evidence of an INS-independent phenotype. RU5 was introduced at the proximal 5′ UTR of the luceriferase reporter gene plasmid pGL3 (Promega), which constitutively expresses luc mRNA from the SV40 late transcriptional control sequences, contains an optimized Kozak consensus sequence and lacks introns. Introduction of RU5 produced a threefold increase in Luc production (Fig. 2; Table 1). Insertion of two copies of SNV RU5 (pSV40RU52luc) did not further augment Luc production, indicating either that the 5′-proximal position of SNV RU5 is necessary for stimulation of Luc production or that insufficient host factors are available for additional stimulation. The stimulatory effect of SNV RU5 was also analyzed adjacent to the CMV IE transcriptional control sequences in pCMVluc. A similar twofold increase was observed when RU5 was introduced in the sense, but not antisense, orientation, indicating that RU5 functions in an orientation-dependent manner and that the stimulatory effect is not attributable to the increased length of the 5′ UTR (Fig. 2; Table 1). These results with two distinct luc reporter gene plasmids indicate that SNV RU5 contains stimulatory sequences that augment expression of reporter gene RNA that lacks INSs.

FIG. 2.

Summary of the structures of the luc reporter plasmids. Labeled 5′-terminal ovals, SV40 late or CMV IE promoter-enhancer; labeled 5′-terminal box, SNV U3 promoter-enhancer; black line, luc 5′ UTR; labeled white rectangle, luc coding region; 3′-terminal oval labeled p(A), polyadenylation signal; RU5, R and U5 regions of the SNV LTR. The arrow indicates the antisense orientation of the SNV RU5. All plasmids contain identical 5′ UTRs from pGL3.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Luc production and luc RNA expressiona

| Plasmid | Luc production, RLUc (mean ± SD) |

luc RNA levelb

|

luc RNA translation efficiencye | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear | Cytoplasmic | Cytoplasmic/nuclear ratiod | |||

| pSV40luc | 7,000 ± 200 (0.12) | NDf | ND | ND | ND |

| pSV40RU5luc | 20,000 ± 500 (0.35) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| pSV40RU52luc | 12,000 ± 300 (0.21) | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| pCMVluc | 31,000 ± 3,000 (0.54) | 29,360 (1.3) | 67,824 (1.3) | 2.3 | 0.41 |

| pCMVasRU5luc | 29,000 ± 4,000 (0.51) | 15,266 (0.7) | 40,582 (0.8) | 2.7 | 0.65 |

| pCMVRU5luc | 53,000 ± 2,500 (0.92) | 30,380 (1.3) | 66,422 (1.3) | 2.2 | 0.74 |

| pSNVluc | 8,800 ± 90 (0.15) | 24,979 (1.1) | 34,230 (0.7) | 1.4 | 0.24 |

| pSNVRluc | 8,000 ± 500 (0.14) | 18,632 (0.8) | 56,616 (1.1) | 3.0 | 0.14 |

| pSNVRU5luc | 57,000 ± 4,000 (1.00) | 23,340 (1.0) | 52,386 (1.0) | 2.2 | 1.00 |

Levels are relative to those of pSNVRU5luc.

RNA was extracted from transfected 293 cells, treated with DNase, subjected to Northern blot analysis with luc and cyp probes, and quantified by PhosphorImager analysis. The numbers in parentheses are luc RNA levels relative to that of pSNVRU5luc.

Luc levels measured in equivalent cell lysates from triplicate transfections of 293 cells normalized to cotransfected Ren values. The numbers in parentheses are Luc levels relative to that of pSNVRU5luc.

Ratio of PhosphorImager value of luc RNA in cytoplasmic sample to that in the nuclear sample.

Ratio of Luc protein to luc cytoplasmic RNA level.

ND, not determined.

Mutational analysis of RU5 in SNV-based luc reporter gene plasmids also indicated that RU5 augments expression of Luc. Deletion of RU5 (pSNVluc) or U5 (pSNVRluc) reduced Luc production by a factor of 7 compared to the intact LTR (pSNVRU5luc), revealing that U5 is necessary for maximal Luc production (Fig. 2; Table 1).

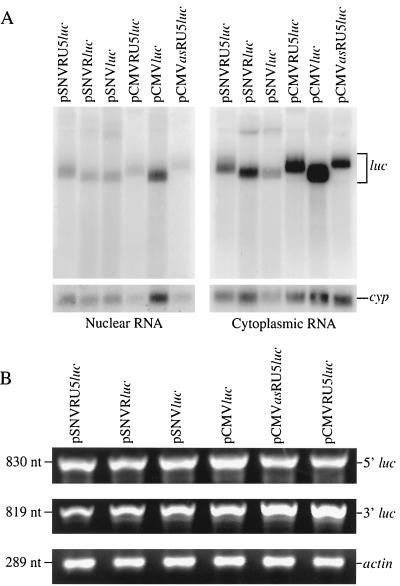

SNV RU5 does not modulate steady-state RNA levels or nuclear export.

RNA analyses were performed to determine if the increases in Luc production in response to RU5 sequences were attributable to increases in steady-state luc RNA or nuclear export efficiency. Northern analysis of nuclear RNA from cells transfected with the SNV- and CMV-based plasmids detected the expected luc transcripts (Fig. 3A). The minor differences in transcript size were expected and are attributable to the deletions of R and RU5. In addition, RT-PCR was performed with two overlapping sets of luc primers that together encompass the entire luc RNA (5′ 830 nt and 3′ 819 nt). The expected single product was observed, confirming that the luc transcript was not disrupted by a splicing event (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of luc RNA in transfected 293 cells. (A) Northern blot analysis of luc transcripts in nuclear or cytoplasmic RNA. RNAs were treated with DNase, and 1 μg of treated RNA was subjected to electrophoresis on a 1.2% agarose gel with 5% formaldehyde, transferred to a Duralon-UV membrane, and hybridized to α-32P-labeled DNA probes complementary to luc and cyp. The blots were subjected to PhosphorImager analysis. Lanes are labeled with the corresponding transfected plasmid. (B) RT-PCR analysis of luc transcripts in cytoplasmic RNA. Primers used are complementary to either the 5′ or 3′ half of luc, coordinates 274 to 1114 and 1112 to 1930 of pGL3-promoter (Promega), respectively, and the actin gene. Lanes are labeled with the corresponding transfected plasmid, product size, and amplified RNA.

The luc RNA levels in the Northern blots of nuclear and cytoplasmic preparations were quantified and normalized to levels of the cellular cyp RNA to control for differences in RNA loading. Similar steady-state luc RNA levels were observed in the presence as well as in the absence of RU5 from either the SNV- or CMV-based plasmids (Table 1). Similar nuclear-to-cytoplasmic RNA ratios were observed in the presence and in the absence of RU5. The data indicate that the increased Luc production was not attributable to increased transcription, stability, or cytoplasmic accumulation of luc RNA. The observation of comparable luc RNA levels despite differences in Luc protein production indicated that RU5 increases translational efficiency (Table 1). The magnitude of increased translational efficiency was most dramatic for the SNV-based plasmids.

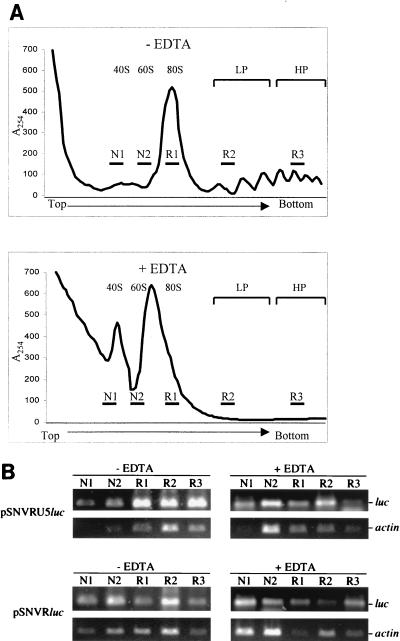

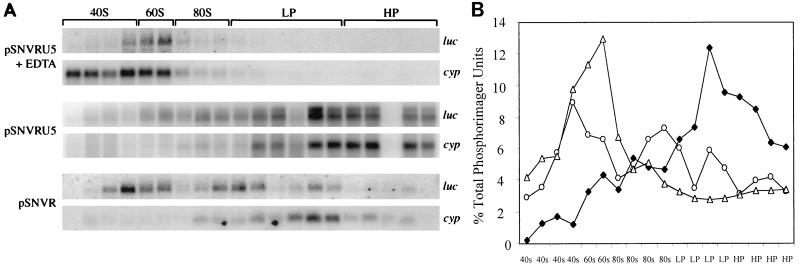

SNV U5 enhances ribosomal association.

To quantify the effect of U5 on luc translational efficiency, the polyribosomal abundance of luc mRNA was evaluated by ribosomal profile and RT-PCR or Northern blot analyses. As expected, the ribosomal profile of cells transfected with pSNVRU5luc is similar to that of cells transfected with pSNVRluc, and ribosomes are disrupted upon incubation with EDTA (representative profiles are shown in Fig. 4A). RT-PCR analysis of five selected fractions revealed that, as expected, the ribosomal association of luc and actin RNAs is sensitive to EDTA and validated the authentic ribosomal association of the transcripts (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Evaluation of cytoplasmic RNA distribution by ribosomal profile analysis. (A) Representative ribosomal profiles of 293 cells transfected with pSNVRU5luc or pSNVRluc. Cytoplasmic extracts were subjected to sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation, fractionation, and spectrophotometry (A254). Positions of 40S and 60S ribosomal subunits, 80S monosomes, light polyribosomes (LP; two to four ribosomes), and heavy polyribosomes (HP; five to eight ribosomes) are indicated. RNA in five fractions (indicated by the labeled horizontal bars) was subjected to RT-PCR. − EDTA and + EDTA, gradients were prepared in the absence or presence of EDTA, respectively; N, nonribosomal fraction; R, ribosomal fraction. The arrow indicates the direction of the gradient. (B) RT-PCR analysis of ribosomal profile RNA. RNA samples were treated with DNase and then incubated with RT, and the cDNA was amplified with primers complementary to luc or the actin gene, visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis, and quantified by Alpha Imager (Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, Calif.) analysis. On each panel are noted the transfected plasmid, RT-PCR product, presence (+) or absence (−) of EDTA in the gradient, and fraction number. Parallel reactions performed without RT were negative, confirming that the samples lacked DNA. Titration of input cDNA and PCR cycle number established that the reactions were in the linear range.

Quantification of luc transcript levels indicated that the overall cytoplasmic quantities of luc transcripts in response to the two plasmids were similar (Fig. 4B; Table 2). These data are in agreement with those of the previous Northern analysis indicating that U5 does not increase the steady-state level of luc mRNA. Evaluation of the cytoplasmic distribution of the luc mRNA in the five samples indicated that U5 increased the abundance of luc mRNA in 80S monosomes (fraction R1) and polyribosomes (fractions R2 and R3) (Fig. 4B). For pSNVRU5luc, the ratio of luc mRNA in ribosomal fractions (R1 plus R2 plus R3) to that in nonribosomal fractions (N1 plus N2) was 4:1, whereas for pSNVRluc the relative abundance was 1.4:1.0 (Table 2). These data reveal a threefold increase in ribosomal association of luc RNA in response to U5. The ratios were reduced to 0.6:1.0 and 0.4:1.0, respectively, upon addition of EDTA, as expected for authentic ribosomal association of the luc RNA.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Luc production and luc cytoplasmic RNA distributiona

| Plasmid | Luc activity (RLU)c | Relative luc RNA levelb

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − EDTA

|

Ratio | + EDTA

|

||||||||||||

| Cytod | N1 | N2 | R1 | R2 | R3 | N1 | N2 | R1 | R2 | R3 | Ratio | |||

| pSNVRU5luc | 57,000 ± 4,000 | 1.00 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 4.0 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.18 | 0.33 | 0.10 | 0.6 |

| pSNVRluc | 8,000 ± 500 | 0.92 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 1.4 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.4 |

Levels are relative to those of pSNVRU5luc.

Cytoplasmic extracts of transfected 293 cells were subjected to ribosomal profile analysis in the presence (+) and absence (−) of EDTA (Fig. 4A). The indicated fractions were treated with DNase, and RNA was amplified by RT-PCR with luc and actin gene primers. RT-PCR products were separated on agarose gels and quantified by Alpha Imager analysis. The Alpha Imager signals were tallied and are presented as percentages of the total signal. N and R, nonribosomal and ribosomal fractions, respectively (numbering corresponds to fractions indicated in Fig. 4A). Ratio, ratio of R1 plus R2 plus R3 to N1 plus N2.

Luc activity was measured in equivalent cell lysates from triplicate transfections.

Cyto, combined values of all cytoplasmic RNA samples normalized to actin RNA level.

To more completely analyze the cytoplasmic distribution of luc RNA, all 20 fractions of the ribosomal profile were subjected to Northern blot analysis. The ribosomal association of luc and cyp RNAs was sensitive to EDTA, confirming authentic ribosomal association of the transcripts (Fig. 5A). The distribution of luc RNA across the profiles again indicated that U5 increased the abundance of luc mRNA in polyribosomes (Fig. 5B). For pSNVRU5luc, the relative abundance of luc mRNA in the polyribosomal fractions was increased 3.4-fold compared to that for pSNVRluc. The results from Northern blot analyses across the entire profile and from RT-PCRs of representative samples both indicate that U5 facilitates a threefold increase in polyribosomal association. These results demonstrate that SNV U5 contains stimulatory sequences that increase translational efficiency by enhancing the polyribosomal association of mRNA.

FIG. 5.

Northern blot analysis of RNA across the ribosomal profiles. (A) Cytoplasmic extracts were subjected to sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation, fractionation, and spectrophotometry (A254). Each fraction was precipitated with ethanol, treated with RNase, and separated on a 1.2% agarose gel containing 5% formaldehyde. Membranes were hybridized with [α-32P]-dCTP-labeled DNA probes complementary to luc and cyp. RNA levels were quantified by PhosphorImager analysis. On each blot are noted the transfected plasmid and the luc or cyp transcript. Horizontal labels indicate the corresponding region of the ribosomal profile. +EDTA, gradient was performed in the presence of EDTA; 40S, 40S ribosomal subunits; 60S, 60S ribosomal subunits; 80S, 80S ribosomal subunits; LP, light polyribosomes (two to four ribosomes); HP, heavy polyribosomes (five to eight ribosomes). (B) Quantification of luc RNA levels across the ribosomal profiles. luc RNA levels were quantified by PhosphorImager analysis, tallied, and expressed as percentages of total PhosphorImager units. ⧫, pSNVRU5luc; ○, pSNVRluc; ▵, pSNVRU5luc plus EDTA.

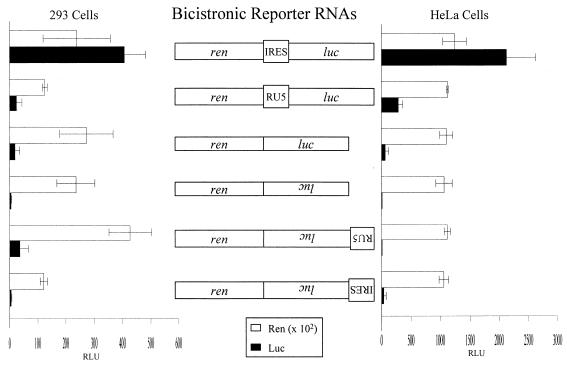

SNV RU5 is not an IRES.

A number of viruses utilize an IRES to enhance translational efficiency of highly structured mRNA (3, 17–19, 25, 41). To evaluate whether RU5 is an IRES, RU5 and the IRES of EMCV were independently introduced into a bicistronic reporter plasmid. The bicistronic reporter plasmid encodes Renilla luciferase (Ren) in the first cistron and luc in the second cistron, which is IRES dependent (Fig. 6). Ren production is a measure of transfection efficiency, and Luc production is a measure of IRES activity. The IRES from EMCV (34) provided high-level Luc production in either 293 or HeLa cells (Fig. 6). By contrast, SNV RU5 consistently produced baseline levels of Luc that were similar to the negative controls, which either lacked an IRES or contained antisense luc. These results confirm that RU5 does not function in a 5′-distal position and eliminate the possibility that RU5 is an IRES.

FIG. 6.

Summary of bicistronic reporter RNAs and corresponding Luc activity in transfected 293 or HeLa cells. Cultures were transfected in triplicate with the bicistronic plasmids, and reporter gene activities (in RLU) in equivalent cell lysate were measured by a dual luciferase assay (Promega). Luc levels are presented relative to transfection efficiency (Ren level). Rectangles labeled in the reverse orientation denote the antisense orientation of the indicated sequence. Labeled rectangles, coding region of ren and luc; RU5, SNV posttranscriptional control element.

DISCUSSION

SNV RU5 stimulates translational efficiency independently of INSs.

The major conclusion of this study is that SNV RU5 sequences stimulate the translational efficiency of reporter gene RNA. Ribosomal profile analysis of SNV-based luc reporter plasmids determined that U5 stimulated polyribosomal association of luc mRNA threefold and increased protein production sevenfold (Fig. 5; Table 1). These data confirm and extend previous results showing that the SNV LTR stimulates translation of HIV gag reporter gene RNA. The RRE/Rev dependence of HIV gag reporter gene RNA has been attributed to cis-acting INSs in HIV mRNA, which function to repress cytoplasmic accumulation (37, 38). In the present study, three pieces of data indicate that RU5 functions independently of INSs in HIV gag. First, Gag expression from pSNVRU5gag is augmented upon inactivation of INS-1, indicating that RU5 does not neutralize the inhibitory effect of INS-1 (Fig. 1). Second, expression of luc RNA, which lacks INSs, is stimulated by RU5 (Table 1). Third, luc RNA is subject to efficient nuclear export that is not augmented by RU5 (Table 1). Our data do not exclude the possibility that RU5 interacts with host proteins that play a role in posttranscriptional regulation by RRE/Rev but instead indicate that RU5 does not function exclusively to neutralize INSs.

RU5 is not an IRES and requires a 5′-proximal position.

Internal ribosome entry is a distinct mechanism by which initiation of translation of a number of viral and cellular mRNAs that encode IRESs is enhanced. IRESs have been identified in the 5′ UTRs of some simple retroviruses, although their importance in modulating retroviral translational efficiency has not been established. In particular, an IRES was identified in reticuloendotheliosis virus type A, an avian retrovirus that is highly related to SNV (25). A 129-nt region in the distal 5′ UTR adjacent to the gag AUG of reticuloendotheliosis virus type A was shown to function as an IRES in a bicistronic reporter (25). RU5 is distinct from this 129-nt region in position, and it does not function as an IRES in a biscistronic reporter gene assay (Fig. 6).

The functional importance of the 5′-proximal position of RU5 has been addressed by experiments here and in previous work. In previous work, it was determined that the ability to facilitate RRE/Rev-dependent HIV gag expression was abrogated when RU5 was positioned in the 3′ UTR (5). Here, results of studies with bicistronic plasmids confirmed that stimulation of luc translation was abrogated when RU5 was repositioned 1,100 nt downstream of the 5′ RNA terminus (Fig. 6). Also, results of experiments with pSV40RU52luc (Table 1) showed that the positive effect of RU5 was not increased by the presence of two copies of RU5, consistent with a strict requirement for a 5′-proximal position. In the case of translational regulation by the iron response element, the potency of translational control is successively reduced when this element is displaced more that 67 nt from the 5′ RNA terminus (13). Future experiments will investigate the precise spacing, relative to the +1 position, that is necessary for translation stimulation by RU5.

Distinctions in posttranscriptional function of RU5 of related simple retroviruses.

Cupelli et al. have shown that the R region of murine leukemia virus (MLV) is important for gene expression from the MLV LTR (7) and that MLV R sequences specifically increase the expression of unspliced RNAs (40). In contrast, previous experiments with HIV gag reporter plasmids indicated that SNV RU5 does not specifically increase cytoplasmic accumulation of unspliced RNAs but stimulates polysomal localization of both spliced and incompletely spliced HIV RNAs (5). Substitution of MLV R with R of chicken synctial virus (CSV), a member, along with SNV, of the reticuloendotheliosus virus type A family, partially augments expression of the MLV reporter gene plasmid (7). Other results with CSV-cat reporter plasmids also showed CSV R to be important for reporter gene expression (36). Deletion of CSV R reduced chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activity to 30% of that of the RU5-containing plasmid. In contrast to our results with SNV, a CSV U5 deletion had little effect on CAT production, reducing the level to 70% and suggesting that R, but not U5, is sufficient for efficient CAT expression. Our results with luc (Table 1), and previously with HIV gag reporter plasmids (5), indicate that SNV R is not sufficient for efficient reporter gene expression. Similar low-level Luc production has been observed from SNV luc plasmids with the SNV U3 promoter-enhancer alone or with R. In contrast, the presence of SNV U5 correlates with maximal reporter gene production. Deletion of U5 (and RU5) reduces Luc production to 15% (Table 1) and HIV gag production to 30% (5) of the wild-type levels. These apparent differences between the RU5 regions of MLV, CSV, and SNV may be attributable to distinctions in the reporter gene plasmids or functional differences in the viral sequences.

RU5 may have evolved to modulate translation of highly structured retroviral RNA.

The highly structured motifs in the 5′ UTRs of retroviral RNA correspond to cis-acting sequences that are necessary for various steps in replication, including viral RNA packaging (44). An intriguing possibility is that SNV RU5 evolved to modulate efficient translation of the highly structured 5′ UTR. Highly structured 5′ UTRs have been shown to inhibit translational efficiency, possibly by impeding cap-dependent ribosome scanning (11, 14, 16, 20–23, 29–31, 35, 42, 43). To circumvent this problem, some viral and cellular RNAs utilize an IRES to facilitate internal ribosome entry and efficient cap-independent translation. Our experiments eliminated the possibility that RU5 is an IRES. Instead, RU5 may have evolved a distinct mechanism to modulate efficient translation of the highly structured SNV RNA. Interestingly, studies with highly structured cellular transcripts have indicated that overexpression of eIF4E increases their translation efficiency (20, 21). eIF4E is the rate-limiting component of the eIF4F translation initiation complex. This complex also contains eIF4A, the prototype of the DEAD-box family, which synergizes with eIF4B to exhibit RNA-dependent ATPase and bidirectional helicase activities (12). It has been proposed that overexpression of eIF4E enhances melting of the inhibitory 5′ RNA structure (21). In SNV RNA, melting of the 5′ UTR structure could distort the RNA packaging signal and impede efficient packaging of the viral transcript. Thus, interaction of RU5 with these cellular translation factors could reduce the packaging efficiency of the RNA. This interaction would represent an important mechanism by which the cytoplasmic commitment of the viral primary transcript as mRNA for translation or virion precursor RNA for packaging is modulated. Identification of host proteins necessary for the translational function of U5 may illuminate how the cytoplasmic fate of SNV RNA is regulated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drew Dangel for invaluable assistance with the ribosomal profile protocol; Melinda Butsch, Patrick Green, and Stacey Hull for critical comments on the manuscript; and Barbara K. Felber for the gift of p37 and p37M1-4.

This work was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society, Ohio Division; the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R29AI40851); and the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md. (P30CA16058).

REFERENCES

- 1.Arrigo S J, Chen I S. Rev is necessary for translation but not cytoplasmic accumulation of HIV-1 vif, vpr, and env/vpu2 RNAs. Genes Dev. 1991;5:808–819. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aziz N, Munro H N. Iron regulates ferritin mRNA translation through a segment of its 5′ untranslated region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8478–8482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berlioz C, Darlix J-L. An internal ribosomal entry mechanism promotes translation of murine leukemia virus gag polyprotein precursors. J Virol. 1995;69:2214–2222. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2214-2222.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bray M, Prasad S, Dubay J W, Hunter E, Jeang K T, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold M L. A small element from the Mason-Pfizer monkey virus genome makes human immunodeficiency virus type 1 expression and replication Rev-independent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1256–1260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butsch M, Hull S, Wang Y, Roberts T M, Boris-Lawrie K. The 5′ RNA terminus of spleen necrosis virus contains a novel posttranscriptional control element that facilitates human immunodeficiency virus Rev/RRE-independent Gag production. J Virol. 1999;73:4847–4855. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4847-4855.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cochrane A W, Jones K S, Beidas S, Dillon P J, Skalka A M, Rosen C A. Identification and characterization of intragenic sequences which repress human immunodeficiency virus structural gene expression. J Virol. 1991;65:5305–5313. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.10.5305-5313.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cupelli L, Okenquist S A, Trubetskoy A, Lenz J. The secondary structure of the R region of a murine leukemia virus is important for stimulation of long terminal repeat-driven gene expression. J Virol. 1998;72:7807–7814. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7807-7814.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D'Agostino D M, Felber B K, Harrison J E, Pavlakis G N. The Rev protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 promotes polysomal association and translation of gag/pol and vpu/env mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1375–1386. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emerman M, Vazeux R, Peden K. The rev gene product of the human immunodeficiency virus affects envelope-specific RNA localization. Cell. 1989;57:1155–1165. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felber B K, Hadzopoulou-Cladaras M, Cladaras C, Copeland T, Pavlakis G N. rev protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 affects the stability and transport of the viral mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1495–1499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geballe A P, Gray M K. Variable inhibition of cell-free translation by HIV-1 transcript leader sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:4291–4297. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.16.4291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gingras A-C, Raught B, Sonenberg N. eIF4 initiation factors: effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:913–963. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goossen B, Hentze M W. Position is the critical determinant for function of iron-responsive elements as translational regulators. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1959–1966. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guan K L, Weiner H. Influence of the 5′-end region of aldehyde dehydrogenase mRNA on translational efficiency. Potential secondary structure inhibition of translation in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17764–17769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hadzopoulou-Cladaras M, Felber B K, Cladaras C, Athanassopoulos A, Tse A, Pavlakis G N. The rev (trs/art) protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 affects viral mRNA and protein expression via a cis-acting sequence in the env region. J Virol. 1989;63:1265–1274. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.3.1265-1274.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hentze M W, Caughman S W, Rouault T A, Barriocanal J G, Dancis A, Harford J B, Klausner R D. Identification of the iron-responsive element for the translational regulation of human ferritin mRNA. Science. 1987;238:1570–1573. doi: 10.1126/science.3685996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hershey J W B, Mathews M B, Sonenberg N, editors. Translational control. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 71–112. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jang S K, Davies M V, Kaufman R J, Wimmer E. Initiation of protein synthesis by internal entry of ribosomes into the 5′ nontranslated region of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA in vivo. J Virol. 1989;63:1651–1660. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.4.1651-1660.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang S K, Kräusslich H-G, Nicklin M J H, Duke G M, Palmenberg A C, Wimmer E. A segment of the 5′ nontranslated region of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA directs internal entry of ribosomes during in vitro translation. J Virol. 1988;62:2636–2643. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.2636-2643.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kevil C G, De Benedetti A, Payne D K, Coe L L, Laroux F S, Alexander J S. Translational regulation of vascular permeability factor by eukaryotic initiation factor 4E: implications for tumor angiogenesis. Int J Cancer. 1996;65:785–790. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960315)65:6<785::AID-IJC14>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koromilas A E, Lazaris-Karatzas A, Sonenberg N. mRNAs containing extensive secondary structure in their 5′ non-coding region translate efficiently in cells overexpressing initiation factor eIF-4E. EMBO J. 1992;11:4153–4158. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05508.x. . (Erratum, 11:5138.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kozak M. Influences of mRNA secondary structure on initiation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:2850–2854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kozak M. Features in the 5′ non-coding sequences of rabbit alpha- and beta-globin mRNAs that affect translational efficiency. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:95–110. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(05)80019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawrence J B, Cochrane A W, Johnson C V, Perkins A, Rosen C A. The HIV-1 Rev protein: a model system for coupled RNA transport and translation. New Biol. 1991;3:1220–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Lastra M, Gabus C, Darlix J-L. Characterization of an internal ribosomal entry segment within the 5′ leader of avian reticuloendotheliosis virus type A RNA and development of novel MLV-REV-based retroviral vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:1855–1865. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.16-1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maldarelli F, Martin M A, Strebel K. Identification of posttranscriptionally active inhibitory sequences in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA: novel level of gene regulation. J Virol. 1991;65:5732–5743. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5732-5743.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malim M H, Cullen B R. Rev and the fate of pre-mRNA in the nucleus: implications for the regulation of RNA processing in eukaryotes. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6180–6189. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.6180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malim M H, Hauber J, Le S Y, Maizel J V, Cullen B R. The HIV-1 rev trans-activator acts through a structured target sequence to activate nuclear export of unspliced viral mRNA. Nature. 1989;338:254–257. doi: 10.1038/338254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manzella J M, Blackshear P J. Regulation of rat ornithine decarboxylase mRNA translation by its 5′-untranslated region. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11817–11822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miele G, Mouland A, Harrison G P, Cohen É, Lever A M L. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 5′ packaging signal structure affects translation but does not function as an internal ribosome entry site structure. J Virol. 1996;70:944–951. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.944-951.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niepel M, Ling J, Gallie D R. Secondary structure in the 5′-leader or 3′-untranslated region reduces protein yield but does not affect the functional interaction between the 5′-cap and the poly(A) tail. FEBS Lett. 1999;462:79–84. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01514-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogert R A, Lee L H, Beemon K L. Avian retroviral RNA element promotes unspliced RNA accumulation in the cytoplasm. J Virol. 1996;70:3834–3843. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3834-3843.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pasquinelli A E, Ernst R K, Lund E, Grimm C, Zapp M L, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold M L, Dahlberg J E. The constitutive transport element (CTE) of Mason-Pfizer monkey virus (MPMV) accesses a cellular mRNA export pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:7500–7510. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.24.7500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pelletier J, Kaplan G, Racaniello V R, Sonenberg N. Cap-independent translation of poliovirus mRNA is conferred by sequence elements within the 5′ noncoding region. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:1103–1112. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.3.1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pelletier J, Sonenberg N. Insertion mutagenesis to increase secondary structure within the 5′ noncoding region of a eukaryotic mRNA reduces translational efficiency. Cell. 1985;40:515–526. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridgway A A, Kung H J, Fujita D J. Transient expression analysis of the reticuloendotheliosis virus long terminal repeat element. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:3199–3215. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.8.3199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneider R, Campbell M, Nasioulas G, Felber B K, Pavlakis G N. Inactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibitory elements allows Rev-independent expression of Gag and Gag/protease and particle formation. J Virol. 1997;71:4892–4903. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.4892-4903.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz S, Campbell M, Nasioulas G, Harrison J, Felber B K, Pavlakis G N. Mutational inactivation of an inhibitory sequence in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 results in Rev-independent gag expression. J Virol. 1992;66:7176–7182. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7176-7182.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz S, Felber B K, Pavlakis G N. Distinct RNA sequences in the gag region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 decrease RNA stability and inhibit expression in the absence of Rev protein. J Virol. 1992;66:150–159. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.150-159.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trubetskoy A M, Okenquist S A, Lenz J. R region sequences in the long terminal repeat of a murine retrovirus specifically increase expression of unspliced RNAs. J Virol. 1999;73:3477–3483. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3477-3483.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Iizuka N, Kohara M, Nomoto A. Internal ribosome entry site within hepatitis C virus RNA. J Virol. 1992;66:1476–1483. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1476-1483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vega Laso M R, Zhu D, Sagliocco F, Brown A J, Tuite M F, McCarthy J E. Inhibition of translational initiation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a function of the stability and position of hairpin structures in the mRNA leader. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6453–6462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Y, Newton D C, Robb G B, Kau C L, Miller T L, Cheung A H, Hall A V, VanDamme S, Wilcox J N, Marsden P A. RNA diversity has profound effects on the translation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12150–12155. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang S, Temin H M. A double hairpin structure is necessary for the efficient encapsidation of spleen necrosis virus retroviral RNA. EMBO J. 1994;13:713–726. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06311.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]