Abstract

Aberrant aggregates of amyloid‐β (Aβ) and tau protein (tau), called amyloid, are related to the etiology of Alzheimer disease (AD). Reducing amyloid levels in AD patients is a potentially effective approach to the treatment of AD. The selective degradation of amyloids via small molecule‐catalyzed photooxygenation in vivo is a leading approach; however, moderate catalyst activity and the side effects of scalp injury are problematic in prior studies using AD model mice. Here, leuco ethyl violet (LEV) is identified as a highly active, amyloid‐selective, and blood‐brain barrier (BBB)‐permeable photooxygenation catalyst that circumvents all of these problems. LEV is a redox‐sensitive, self‐activating prodrug catalyst; self‐oxidation of LEV through a hydrogen atom transfer process under photoirradiation produces catalytically active ethyl violet (EV) in the presence of amyloid. LEV effectively oxygenates human Aβ and tau, suggesting the feasibility for applications in humans. Furthermore, a concept of using a hydrogen atom as a caging group of a reactive catalyst functional in vivo is postulated. The minimal size of the hydrogen caging group is especially useful for catalyst delivery to the brain through BBB.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, amyloid, ethyl violet, photooxygenation catalyst, prodrug

Leuco ethyl violet (LEV), identified as a highly active, amyloid‐selective, and blood‐brain barrier permeable photooxygenation catalyst, functions as a self‐activating pro‐catalyst. Under photoirradiation, LEV undergoes self‐oxidation through a hydrogen atom transfer process, forming catalytically active ethyl violet (EV) in amyloid's presence. This enables in vivo photooxygenation of amyloid‐β without inducing scalp injury and facilitates the oxygenation of amyloids in Alzheimer disease patients.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a chronic, progressive, neuro‐degenerative brain disorder associated with loss of memory and cognitive decline.[ 1 ] AD is pathologically characterized by two types of lesions: senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. These are composed of aberrantly aggregated amyloid‐β (Aβ) and tau, respectively. Protein aggregates like these are called amyloid.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ] Decreasing amyloid levels in AD patients is an effective treatment of AD; the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved two monoclonal antibodies to Aβ, aducanumab[ 6 ] and lecanemab,[ 7 ] as anti‐AD drugs. The switch from biologics to small‐molecule drugs acting as functional surrogates of biologics, will be an important next step.

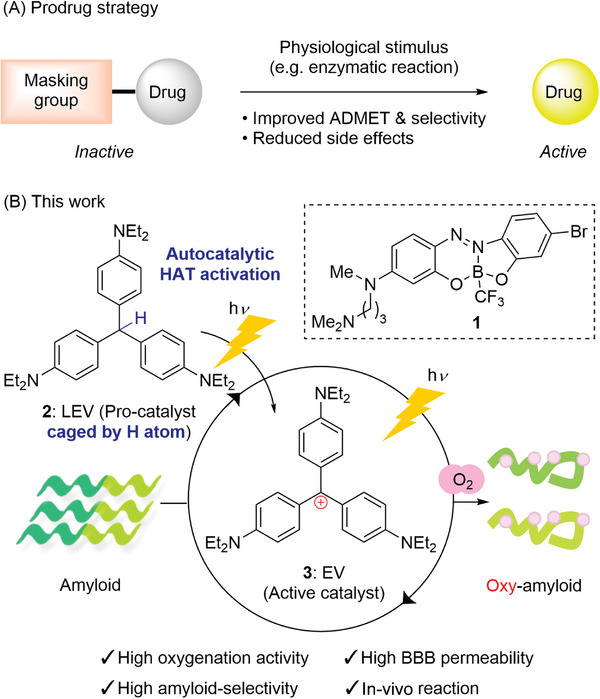

Degradation of amyloids using small‐molecule catalysts is an emerging approach.[ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ] Targeting the cross‐β‐sheet structure characteristic to amyloids, we previously developed amyloid‐selective photooxygenation catalysts.[ 18 , 19 , 20 ] When interacting with the cross‐β‐sheet structure, these catalysts acted as photosensitizers to generate singlet oxygen (1O2) under light irradiation. Due to the short‐lived nature of 1O2, it reacted selectively with the proximal amyloid. Specific amino acid residues, such as histidine (His)[ 21 ] and/or methionine (Met), were oxygenated. The covalent installation of hydrophilic oxygen functionalities into amyloid decreased its aggregative propensity and toxicity. Furthermore, catalyzed photooxygenation of Aβ amyloid facilitated its phagocytotic degradation by microglia cells in the mouse brain.[ 22 ] Specifically, we achieved non‐invasive photooxygenation and a significant (ca. 30%) decrease of Aβ amyloid in the brains of living AD model mice through intravenous administration of an azobenzene‐boron complex catalyst (ABB: 1) and light irradiation (λ = 595 nm) to the head.[ 20 ] However, two main challenges remain for catalyst 1. First, the activity was moderate, and photooxygenation did not proceed when using lysate from an AD patient's brain. Second, the treatment induced scalp injury as a side effect, likely due to the low blood‐brain barrier (BBB) permeability and insufficient target selectivity of 1. To overcome these challenges, we investigated using a prodrug strategy (Figure 1A)[ 23 ] with the catalytic treatment, so called catalysis medicine.[ 24 ] This strategy would maximize the efficacy by improving the ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity) properties of a highly active catalyst while reducing its potential toxicity. We envisioned that an external stimulus (photoirradiation in this study) would generate a highly active photocatalyst from a pro‐catalyst with better ADMET properties in the vicinity of amyloid selectively, thereby enabling efficient photooxygenation with minimal side effects.

Figure 1.

Catalytic photooxygenation of amyloids by prodrug strategy. A) General concept of prodrug strategy. B) Photooxygenation of amyloids by leuco ethyl violet 2 as a procatalyst.

In this study, we report that leuco ethyl violet (LEV: 2) functions as a less toxic and BBB‐permeable pro‐catalyst of ethyl violet (EV: 3), whose photooxygenation activity is two orders of magnitude greater than that of ABB 1 (Figure 1B). Photoirradiation to 2 locally generates catalytically active 3 near amyloid through an autocatalytic hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) mechanism, enabling selective photooxygenation of Aβ amyloid. The high BBB permeability and amyloid selectivity of 2 have allowed us to achieve in vivo photooxygenation of Aβ without scalp injury. Furthermore, 2 can oxygenate AD patient‐derived human Aβ and tau amyloids, suggesting its potential as a multi‐targeting agent for the treatment of AD.

2. Results and Discussion

We envisioned trityl cations as a new photocatalyst scaffold with greater activity than 1. The heteroatom‐substituted triarylmethane dyes (hsTMDs) are stable trityl cations of wide utility, being used as fluorescent probes,[ 25 , 26 , 27 ] pH indicators,[ 28 , 29 ] photocatalysts,[ 30 , 31 ] and drugs.[ 32 ] In the photoexcited state, hsTMDs furnish n–π* electron transition, which facilitates the intersystem crossing (ISC) process[ 33 ] and enhances the photooxygenation activity. In addition, their molecular size is generally small, while still absorbing relatively long‐wavelength light. This property is advantageous to BBB permeability[ 34 ] and in vivo applications. Furthermore, hsTMDs bear an aggregation‐induced emission (AIE) switch[ 35 , 36 ] to turn on/off depending on the environment (i.e., binding/non‐binding to amyloids), like Thioflavin T (ThT) dyes do.[ 19 , 37 ] Last but not least, TMDs were reported to bind to Aβ and other amyloids containing cross‐β‐sheet structures and reduce their toxicity and aggregation propensity by acting as aggregation inhibitors.[ 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 ]

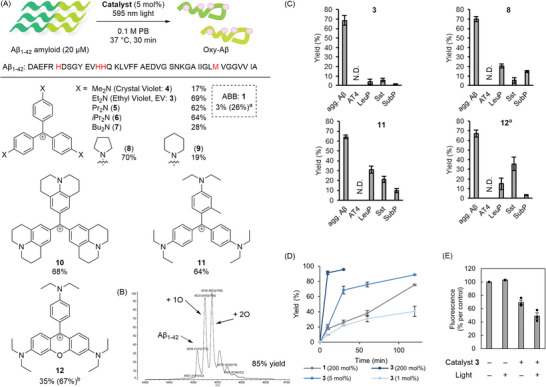

We screened hsTMDs in photooxygenation of aggregated Aβ under 595 nm light irradiation to identify ethyl violet (EV: 3) as the most active and selective catalyst (69% yield, Figures 2A–C and S1, Supporting Information). Oxygenation yield was calculated from MALDI‐TOF MS analysis (Figure 2B). No heavy atom, such as a halogen atom, was required for the photooxygenation activity. The catalyst activity was dependent on the substituents on the nitrogen atoms (3‒10). The balance between water solubility and Aβ binding affinity might be attributable to this tendency. Catalyst 11, bearing an ortho‐methyl group at the trityl core skeleton, and 12, with a rhodamine skeleton, also showed high activity.

Figure 2.

Photooxygenation of aggregated Aβ using triarylmethane catalysts. A) Activity‐based catalyst screening. A 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB) solution (pH 7.4) containing aggregated Aβ1–42 (20 × 10−6 m) and catalyst (1 × 10−6 m, 5 mol%) was photoirradiated (λ = 595 nm, 10 mW) at 37 °C for 30 min. Oxygenation yield is the sum of the yields of products that are oxygenated in at least one sites. Yield was determined by MALDI‐TOF MS analysis (average of n = 3 experiments). a200 mol% instead of 5 mol% catalyst was used. b500 nm light instead of 595 nm light was used. B) A representative MALDI‐TOF MS chart for photooxygenation of Aβ using 3 (EV). C) Evaluation of amyloid selectivity. A PB solution (pH 7.4) containing aggregated Aβ1–42 (agg. Aβ), angiotensine‐IV (AT4: amino acid sequence with underlined potential oxidation sites: VYIHPF), leuprorelin (LeuP: PyroEHWSYLLRP), somatostatin (Sst: AGCKNFFWKTFTSC), or [Tyr8]‐substance P (SubP: RPKPQQFYGLM‐NH2) (20 × 10−6 m each) was photoirradiated (λ = 595 nm, 10 mW) in the presence of catalyst 3 (EV), 8, 11, or 12 (each 1 × 10−6 m, 5 mol%) at 37 °C for 30 min. Yield was analyzed using MALDI‐TOF MS (n = 3 experiments, mean ± SEM). a500 nm light instead of 595 nm light was used. D) Reaction profile. A PB solution (pH 7.4) containing Aβ1–42 (20 × 10−6 m) and 3 (0.2 × 10−6, 1 × 10−6, or 40 × 10−6 m) or ABB (40 × 10−6 m) was photoirradiated (λ = 595 nm, 10 mW) at 37 °C for certain time periods. Yield was analyzed using MALDI‐TOF MS (n = 3 experiments, mean ± SEM). E) Evaluation of amyloidogenic cross‐β‐sheet propensity by Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence assay with or without treatment by catalyst 3 (EV). Lane 4 (catalyst + and light +): A 0.1 m PB solution (pH 7.4) containing monomer Aβ1–42 (20 × 10−6 m) and catalyst 3 (1 × 10−6 m, 5 mol%) was photoirradiated (λ = 595 nm, 10 mW) at 37 °C for 3 h. After the reaction, the aggregation level was evaluated with ThT fluorescence (n = 3 experiments, mean ± SEM).

To evaluate Aβ amyloid selectivity, we compared photooxygenation yield of Aβ with four non‐aggregative peptides (angiotensin IV (AT4), somatostatin (Sst), leuprorelin (LeuP), and [Tyr8]‐substance P (SubP)) as off‐target models, using catalysts with high activity (3, 8, 11, or 12) (Figure 2C). Yield for the photooxygenation of the non‐aggregative peptides was less than 6% using 3, while it was 13–35% using 8, 11, or 12. The high off‐target oxygenation level using 8 was likely due to the self‐aggregation of the catalyst in an aqueous solvent; the absorption spectrum of 8 showed a larger peak ratio at 600 nm/ca. 550 nm than 3 did, suggesting formation of self‐aggregates[ 44 ] (Figures S2 and S3, Supporting Information). Self‐aggregation would turn on the AIE switch of 8 to generate 1O2 irrespective of the existence of amyloid or promote excimer formation and subsequent single electron reduction of molecular oxygen through a type I mechanism to generate highly oxidative superoxide anion radical (O2 •–).[ 45 ] Compared to 3, the cyclic alkyl amine substituents of 8 diminished the molecular flexibility and steric hindrance, promoting self‐aggregation. For 11 and 12, the single bond rotation between the aryl group and the cationic carbon atom was partly inhibited. This accelerated non‐selective oxygenation of off‐target peptides. We also confirmed the high amyloid selectivity of 3 by using lysozyme as an off‐target non‐aggregative protein model (Figure S4, Supporting Information).

Next, we characterized 3 regarding the reaction kinetics, optical properties, and structures/aggregation propensities of the products. The catalyst activity of 3 was ca. >100 times greater than 1 (Figure 2D). The initial kinetics using 1 mol% 3 were almost comparable to 200 mol% 1, whereas the reaction did not reach completion. This was likely due to catalyst deactivation such as photodegradation during the reaction. However, because photooxygenated Aβ inhibited aggregation of native Aβ and thus markedly decreased the toxicity of Aβ amyloid despite the limited oxygenation (ca. 15% yield),[ 18 , 19 ] 3 can still be effective under low catalyst concentrations, especially in in vivo applications (see Figure 6A and Figure S29, Supporting Information). The maximum absorption wavelength of 3 redshifted from 595 to 603 nm in the presence of Aβ amyloid (Figure S3, Supporting Information). Furthermore, the fluorescence intensity was increased by 19‐fold in the presence of Aβ amyloid (Figure S5, Supporting Information). These optical properties indicate that 3 binds with Aβ amyloid, thereby inhibiting the relaxation process and promoting fluorescence emission. Based on the MALDI‐TOF MS analysis of the Aβ photooxygenation products after enzymatic digestion, the oxygenated amino acid residues were His6, His13, His14, and Met35 (Figure 2A and Figure S6, Supporting Information). It was reported that His oxygenation produced crosslinked products through the intermolecular addition reaction of nucleophilic amino acid residues to the electrophilic oxygenated His intermediates (Figure S7, Supporting Information).[ 21 , 46 ] Thus, a crosslinked fragment of FRHD at the oxygenated His residue was also detected (Figure S6, Supporting Information). The ThT fluorescence intensity, an indicator of the cross‐β‐sheet propensity,[ 37 ] was significantly lower for the photooxygenated products than for the control samples without photooxygenation (Figure 2E). ThT fluorescence also decreased for the catalyst‐only sample. This result suggests that 3 shares the same binding site as ThT on Aβ amyloid.

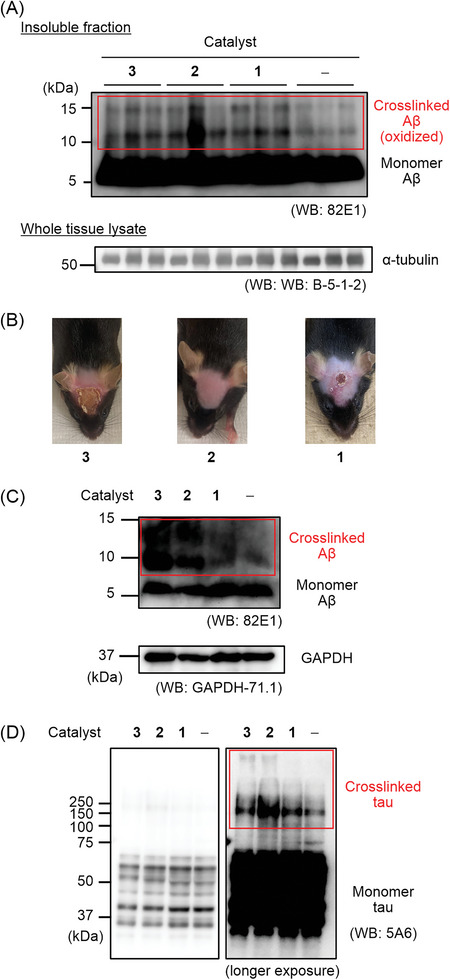

Figure 6.

In vivo and ex‐vivo photooxygenation reaction. A) In vivo photooxygenation reaction. A solution of EV 3, LEV 2, or ABB 1 was intravenously injected into 5–6 month old AppNL‐G‐F/NL‐G‐F mice (n = 3 experiments, each group) expressing human Arctic Aβ. After an interval, the mice were irradiated with LED (λ = 595 nm) for 10 min. The operation set (catalyst injection and photoirradiation) was repeated five times over 5 d. At 24 h after the final operation set, the brain was excised and homogenized using a 1× PBS buffer. After the fractionation, the insoluble fraction was analyzed by SDS‐PAGE using a 15% Tris‐Tricine gel and Western blot (WB) using an anti‐Aβ antibody. For loading controls, α‐tubulin in lysates before fractionation was analyzed. B) Photos of mouse scalp after the photooxygenation treatment in (A). C, D) Catalytic photooxygenation of human brain lysate. The temporal cortex of an AD patient was homogenized using a 10× volume of PBS (containing cOmplete EDTA+ (Roche) and PhosSTOP (Sigma)). A catalyst (2.5 × 10−6 m) was added to the brain lysate and the mixture was irradiated with 595 nm light for 3 h or kept in the dark at 37 °C. The resulting mixture was analyzed with SDS‐PAGE and WB (anti‐Aβ antibodies: 82E1 (IBL) and anti‐GAPDH antibodies: GAPDH‐71.1 for (C), anti‐tau antibodies: 5A6 for (D)). Human AD‐tau is comprised of 6 isoforms, whose sizes are 36.8–45.9 kDa. CBB staining was shown in Figure S30 (Supporting Information).

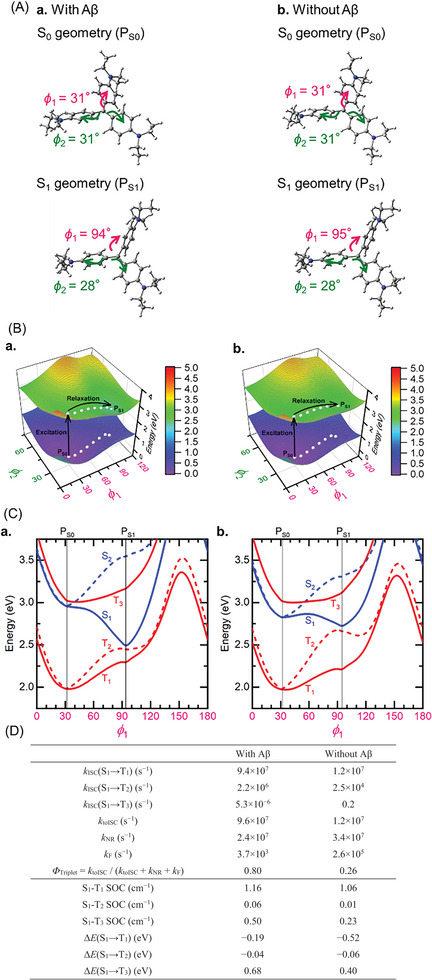

We conducted density functional theory (DFT) calculations to understand why 3 shows a higher triplet generation ability when binding Aβ than when not (Tables S1‒S4, Supporting Information). First, we optimized the ground‐state (S0) geometries of 3 using the M06‐2X/6‐31G(d) method. Second, we optimized the lowest excited singlet state (S1) geometries using the M06‐2X/6‐31G(d) method under Tamm‐Dancoff approximation (TDA). To model 3 without binding Aβ in an aqueous solution, we employed the polarized continuum model and the relative permittivity of water (ε r = 78). Meanwhile, we set ε r = 1 to model 3 binding with Aβ, based on the reported docking structure between 4 and an Aβ trimer model (Figure S8, Supporting Information).[ 43 ] The optimized S0 geometries (denoted PS0) with and without binding Aβ belong to the D 3h symmetry, whereas the optimized S1 geometries (denoted PS1) belong to the C 2 symmetry (Figure 3A). Comparing the optimized S0 and S1 geometries shows that the torsion angle of one of the benzene rings (ϕ 1) increases from 31° to 94°/95° during the geometry relaxation after S0‐S1 excitation. Meanwhile, the torsion angles of the other benzene rings (ϕ 2) essentially do not change (from 31° to 28°). Then, we calculated the S0 and S1 potential energy surfaces for ϕ 1 and ϕ 2 rotations with and without binding Aβ (Figure 3B). White dots on the green surface in Figure 3B show possible decay paths from the S0 to S1 geometries in the S1 state. The ϕ 1 rotation is relevant for the geometry deformation. Finally, we calculated potential energy curves for S0, excited singlet states (S1 and S2), and excited triplet states (T1, T2, and T3) along the decay paths (as a function of ϕ 1) (Figure 3C). There is no crossing point between the potential energy curves of the excited singlet and triplet states, indicating that the transition from the excited state to the ground state proceeds after relaxation to the most stable geometry in the S1 state. All the calculations were performed with the Gaussian 16 program package.[ 47 ]

Figure 3.

DFT calculation of EV (3). A) Optimized S0 and S1 geometries calculated using the M06‐2X/6‐31G(d) and TDA‐M06‐2X/6‐31G(d) methods, respectively. (a) 3 with binding Aβ (ε r = 1); (b) 3 without binding Aβ (ε r = 78). B) Potential energy surfaces for the ground state (S0) and lowest excited singlet states (S1). (a) 3 with binding Aβ (ε r = 1); (b) 3 without binding Aβ (εr = 78). White dots depict geometry relaxation paths. C) Potential energy curves for the excited singlet states (S1 and S2) and excited triplet states (T1, T2, and T3) calculated along the decay paths in Figure 3B. (a) 3 with binding Aβ; (b) 3 without binding Aβ. D) Rate constants for ISC (k ISC), non‐radiative decay (k NR), and fluorescence (k F), spin–orbit couplings (SOCs), and excited‐state energy differences (ΔE), calculated at the TDA‐M06‐2X/6‐31G(d) level of theory.

We calculated the rate constants for S1→T1 ISC (k ISC(S1‐T1)), S1→T2 ISC (k ISC(S1‐T2)), S1→T3 ISC (k ISC(S1‐T3)), S1→S0 fluorescence (k F), and S1→S0 nonradiative decay (k NR) at the optimized S1 geometries (Figure 3D).[ 48 ] We estimated the rate constant of total ISC (k to ISC) and triplet generation quantum yield (ϕTriplet) in 3 as:

| (1) |

| (2) |

The calculated ϕ Triplet is larger for 3 with binding Aβ (0.80) than without binding Aβ (0.26). This is primarily because the k toISC value is more considerable with binding Aβ (9.6 × 107 s−1) than without binding Aβ (1.2 × 107 s−1). The k F values are far smaller than the k toISC values with and without Aβ and do not substantially change ϕ Triplet. From Figure 3D, the k toISC values are almost identical to the k ISC(S1→T1) values, suggesting that the S1→T1 ISC dominates the total ISC process. Thus, the difference in ϕ Triplet is attributed to the difference in k ISC(S1→T1). k ISC(S1→T1) increases by decreasing the S1–T1 energy difference (ΔE) and increasing the S1–T1 spin–orbit coupling (SOC). The theoretical calculations show that the S1–T1 SOCs are of the same order of magnitude regardless of with or without binding Aβ (1.16 and 1.06 cm−1, respectively), suggesting that the smaller ǀΔE(S1–T1)ǀ with binding Aβ (0.19 eV; 0.52 eV without Aβ) is responsible for the larger k ISC(S1→T1). The energy transfer from the excited catalyst in the T1 state to molecular oxygen (3O2) affords 1O2, which reacts with nearby amyloid (Figure S9, Supporting Information). Thus, the activity turn‐on mechanism of 3 by binding amyloid is due to the enhanced ISC kinetics from S1 to T1 by sensing the hydrophobic environment (i.e., small ε r ) of amyloid.

Toward in vivo applications, we evaluated cytotoxicity of catalyst 3 to find that 3 was highly toxic with the LD50 value for PC12 cells to be 0.14 × 10−6 m under dark conditions (Figure S10, Supporting Information). The high toxicity of 3 was likely due to its cationic character and interaction with cell membranes.[ 49 ] We hypothesized that the reduced form 2 would act as a precursor of 3 through autocatalytic oxidation.[ 50 ] This oxidative procatalyst activation would be accelerated in the presence of amyloids, further enhancing the amyloid selectivity. Based on this hypothesis, we synthesized leuco ethyl violet (LEV: 2). As expected, toxicity of 2 was markedly decreased with its LD50 >10 × 10−6 m (Figure S10, Supporting Information). Furthermore, the BBB permeability of 2 was improved compared to 1 and 3; the recovery rates of 2, 1, and 3 from mice brains at 10 min after intravenous injection were 1.7%, 0.58%, and 0.046%, respectively (Figure S11, Supporting Information). The maximum absorption wavelength of 2 blue‐shifted from 288 nm to 283 nm in the presence of Aβ amyloid (Figure S12, Supporting Information), suggesting that 2 interacts with Aβ amyloid.

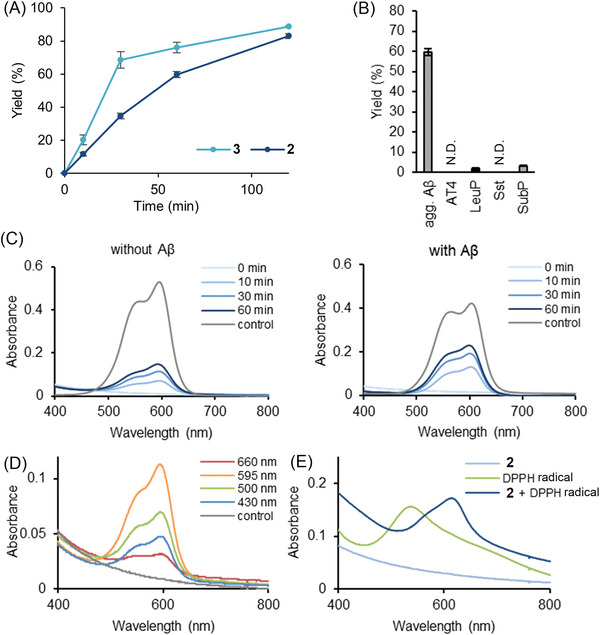

We then studied the photooxygenation ability and selectivity of 2 to Aβ amyloid (Figure 4 ). The reaction proceeded in high yield over 2 h using 5 mol% 2 (Figure 4A and Figure S13, Supporting Information). LEV 2 showed slower kinetics at the initial stage (ca. 1 h) than EV 3, but both catalysts reached comparable yield after 2 h. Photooxygenated Aβ by 2 exhibited decreased cross‐β‐sheet propensity based on the ThT fluorescence detection (Figure S14, Supporting Information), as was observed using 3. The Aβ amyloid selectivity of 2 to off‐target model peptides and a protein (lysozyme) was even higher than that of 3 (Figure 4B and Figures S3 and S15, Supporting Information).

Figure 4.

Photooxygenation of Aβ amyloid using LEV (2). A) Reaction time course. A PB solution (pH 7.4) containing aggregated Aβ1–42 (20 × 10−6 m) and 2 or 3 (1 × 10−6 m, 5 mol%) was photoirradiated (λ = 595 nm, 10 mW) at 37 °C, and the reaction progress was analyzed using MALDI‐TOF MS (n = 3 experiments, mean ± SEM). B) Evaluation of amyloid selectivity. A PB solution (pH 7.4) containing aggregated Aβ1–42 (agg. Aβ), AT4, LeuP, Sst, or SubP (20 × 10−6 m each) was photoirradiated (λ = 595 nm, 10 mW) in the presence of 2 (1 × 10−6 m, 5 mol%) at 37 °C for 60 min. Yield was analyzed using MALDI‐TOF MS (n = 3 experiments, mean ± SEM). C) Spectroscopic time course for the generation of 3 from 2. A PB solution (pH 7.4) containing 2 (20 × 10−6 m) with (right) or without (left) Aβ amyloid (20 × 10−6 m) was photoirradiated (λ = 595 nm, 10 mW) at 37 °C, and the absorption spectra were measured. The control is the absorption spectrum of 3. D) Conversion of 2 to 3 under photoirradiation with variable wavelength light. A PB solution (pH 7.4) containing 2 (20 × 10−6 m) was irradiated at the indicated wavelength (10 mW) at 37 °C for 30 min, and the absorption spectra were measured. The control is the absorption spectrum of 2. E) Activation of 2 to 3 through a hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) process. To a PB solution (pH 7.4) of 2 (20 × 10−6 m), 1,1‐diphenyl‐2‐picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical (20 × 10−6 m) was added and the mixture was incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 30 min under air. After incubation, the absorption spectrum of the solution was measured.

We reasoned that the active catalyst when using 2 is indeed 3, on the basis of the following results. First, we observed the formation of 3 from 2 by photoirradiation at λ = 595 nm either in the absence or presence of Aβ amyloid. The absorption peak at 600 nm, characteristic to 3, increased according to the time course (Figure 4C). The conversion rate was greater in the presence of Aβ than in its absence (54% vs 28% at 60 min). The light‐induced conversion from 2 to 3 was also confirmed by LC‐MS analysis and fluorescence spectroscopy (Figure S16, Supporting Information). This conversion did not proceed without light irradiation. However, the light absorbance of 2 at λ = 595 nm was very weak (Figure S12, Supporting Information). To gain deeper insight into what species absorbs light for the conversion from 2 to 3, we studied this process by irradiating 2 with variable wave‐length light. The formation of 3 was enhanced in the order of λ = 595, 500, 430, and 660 nm (Figure 4D). This tendency is consistent with the absorption coefficient of 3. Therefore, 3 must be responsible for the activation of 2 to 3 and thus this process is autocatalytic.[ 51 ]

Then, we collected mechanistic information for the conversion from 2 to 3. The formation of 3 was retarded under degassed conditions, indicating the involvement of 3O2 (Figure S17, Supporting Information). However, 1O2 was not likely relevant to this process. Thus, the addition of NaN3, a 1O2 scavenger,[ 51 ] did not affect the light‐induced generation of 3 from 2 (Figure S18, Supporting Information). Furthermore, treatment of 2 with 1O2 generated from H2O2 and Na2MoO4 without photoirradiation,[ 52 , 53 ] did not produce 3 (Figure S19, Supporting Information). The addition of 1,1‐diphenyl‐2‐picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical[ 54 ] acting as a hydrogen atom abstracting reagent from the central methine C─H bond of 2, however, led to the formation of 3 under aerobic conditions without photoirradiation (Figure 4E). These results all support that photoexcited 3 works as a hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) catalyst in the activation of 2 to 3.[ 55 ]

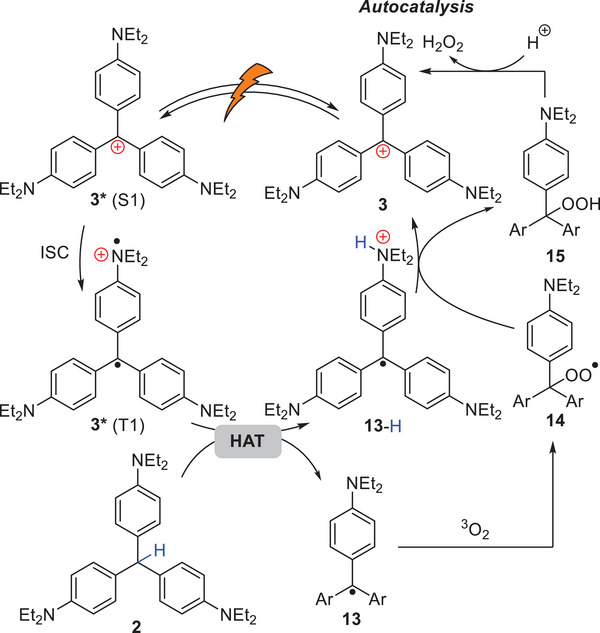

Based on the above results, we proposed a plausible mechanism for the activation of 2 to 3 (Figure 5 ). A small amount of 3 is generated by autooxidation of 2. Photoexcitation of 3, followed by ISC affords excited 3 in a triplet state [3* (T1)], which abstracts the methine hydrogen atom of 2 to generate trityl radicals 13 and 13‐H. DFT calculation suggested that this HAT process is thermodynamically feasible (Figure S20, Supporting Information). 13 reacts with 3O2 to produce peroxy radical 14. Subsequently, the reaction between 13‐H and 14 proceeds through another HAT process, or a stepwise single electron transfer (SET) from 13‐H to 14 followed by proton transfer, to regenerate 3 and hydroperoxide 15. Finally, elimination of hydrogen peroxide from 15 affords 3. The generation of H2O2 in photoirradiation of 2 to form 3 was confirmed by an iodometry experiment (Figure S21, Supporting Information also see Figures S22–S25, Supporting Information, for further mechanistic supports). Furthermore, since the photocatalytic activity of 3 is turned on by binding to Aβ amyloid, the activation from 2 to 3 is also accelerated in the presence of amyloid. This enhances amyloid selectivity of 2 compared to 3. Autocatalytically activated 3 initiates the facilitated generation of 1O2 under photoirradiation in the hydrophobic environment proximate to amyloid, leading to selective oxygenation of the amyloid.

Figure 5.

Proposed mechanism for conversion of 2 to 3.

We confirmed the greater catalytic activity of 2 and 3 compared to 1 using brain lysates derived from AD model mice (AppNL‐G‐F/NL‐G‐F )[ 56 ] expressing Aβ1–38 and Aβ1–42 containing the human Arctic mutation (Figures S26‒S28, Supporting Information).[ 57 ] Then, in vivo photooxygenation of Aβ amyloid in AppNL‐G‐F/NL‐G‐F mice brains was examined. To a 6 month old AppNL‐G‐F/NL‐G‐F mouse containing matured Aβ amyloid,[ 58 ] a catalyst was intravenously injected, and the head of the mouse was irradiated with 595 nm LED light for 10 min. This treatment was repeated 5 times over 5 days. After the treatment, the brain was extracted and the progress of photooxygenation of Aβ was evaluated by Western blot (WB) analysis. When treated with catalyst 1, 2, or 3, Aβ dimer and trimer bands at ca. 10 and 15 kDa, respectively, increased compared to the control samples without the catalyst treatment (Figure 6A).[ 21 ] This result indicates that the catalytic photooxygenation of Aβ indeed proceeded in vivo. Furthermore, while 3 and 1 damaged the mice scalp tissue, the treatment with 2 produced few if any apparent side effects (Figure 6B). This stark difference is likely due to the higher BBB permeability and amyloid selectivity of 2 relative to 1 and 3.

A preventive approach inhibiting amyloid formation through intervention at an early stage of the disease before symptoms appear is also important for AD treatment. To mimic such preventive treatment, we investigated a chronic administration (2 months) of catalyst 2 to 2–3 month old AppNL‐G‐F/NL‐G‐F mice containing less matured Aβ amyloid. The dimer and trimer Aβ bands again increased in the mice brains treated with 2 (Figure S29, Supporting Information). This result suggests the applicability of 2 towards the prevention of AD.

Finally, we investigated the catalytic photooxygenation of Aβ in human AD‐brain lysate. It has been argued that human Aβ fibrils expressed in AD model mice brains do not reproduce the higher‐order structures of Aβ fibrils in human brains of sporadic AD.[ 59 ] Therefore, the applicability of the catalysts to Aβ amyloid in human AD‐brain lysate is critically important. Intensities of the WB bands corresponding to Aβ dimer and trimer were significantly greater for the samples treated with 3 or 2 than the samples treated with 1 or the negative control without treatment (Figure 6C and Figure S30, Supporting Information). Furthermore, we analyzed the effect of these catalysts on tau in the same samples, as aggregated tau is also photooxygenated by another catalyst.[ 60 ] The reaction with an AD patient‐derived tau is challenging due to its large molecular size and the presence of many isoforms and post‐translational modifications. We found that crosslink products of tau also increased following catalytic photooxygenation, especially when using 2 (Figure 6D). These results suggest that 2 can be a multi‐targeting catalyst against Aβ and tau, both of which are related to AD etiology.[ 61 ]

3. Conclusion

Catalytic photooxygenation of amyloid is an emerging approach to the development of therapies treating AD, a cognitive disease currently difficult to cure. Considering the limited light intensity available in the deep brain by non‐invasive light irradiation from outside the body, however, increasing the catalyst activity is critically important from a chemical perspective. In this study, we identified EV 3 as a highly active and amyloid‐selective photooxygenation catalyst. The activity of 3 was two orders of magnitude greater than that of the previous catalyst 1,[ 20 ] which was applicable to non‐invasive in vivo photooxygenation of Aβ amyloid in AD model mice brains. Theoretical calculations rationalized the high activity and selectivity of 3 by the facilitated ISC under a hydrophobic environment when binding to Aβ amyloid. However, 3 was cytotoxic due to its cationic characteristics. Therefore, we developed a procatalyst, LEV 2, which is charge neutral. Photoirradiation in the presence of amyloid activated 2 to generate 3 through an autocatalytic HAT mechanism. Catalyst 2 was less toxic and furnished favorable properties for in vivo applications; high activity and amyloid selectivity, enhanced BBB permeability, and absorption of tissue‐permeable long‐wavelength light. We established the superiority of 2 over 1 and 3 by demonstrating its reduced side effects and applicability to Aβ and tau amyloids derived from a human AD patient.

This is the first demonstration of autocatalytic oxidative activation of a leuco dye used as a caged prodrug by spatiotemporally controllable external stimuli, such as light, without the exogenous addition of other chemical species. This approach has improved ADMET and enhanced amyloid selectivity, while generating a highly active photo‐catalyst on‐demand. A room for improvement is the light wavelength required for the excitation of active catalyst 2 (595 nm). For applications to higher animal models having greater brain size, catalysts activatable by near infrared light is preferable.[ 62 ] Further optimization of the catalyst structure, as well as the development of a photodevice to transfer light energy deep into the body, are currently ongoing.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant numbers JP23H05466 and JP23H04909 (M.K.), JP20H05843 (Dynamic Exciton) and JP21K15220 (H.M.), JP20H05840 (H.K.) (Dynamic Exciton), 22K05252 (K.S.), JP19H01015 (T.T.), JP18K06653 and JP21H02622 (Y.H.), JP16H06277 (CoBiA), JP21H02602 (Y.S.), AMED Grant Numbers JP19dm0107106, JP19dm0307030 and JP22gm6410017 (Y.H.). This research was also supported by JST‐PRESTO Grant Numbers JPMJPR2279 (H.M.). M.F. was supported by a JSPS Research Fellowship for Young Scientists (JP20J22142) and World‐leading Innovative Graduate Study Program for Life Science and Technology (WINGS‐LST). The authors appreciate T.C. Saido (Riken Center for Brain Science) and T. Saito (Nagoya City University) for providing the AD‐model mice. The authors also appreciate J. Q. Trojanowski, V. M. Y. Lee (University of Pennsylvania), Japan Brain Bank Net (JBBN), and the AD patients and their families for human brain donation. The authors thank D. Kitagawa, T. Ohwada, and Y. Otani (University of Tokyo) for allowing us to access to the equipment such as the ultracentrifuge and the Circular Dichroism spectrometer. The computation was performed using the Research Center for Computational Science, Okazaki, Japan (Project: 21‐IMS‐C110).

Furuta M., Arii S., Umeda H., Matsukawa R., Shizu K., Kaji H., Kawashima S. A., Hori Y., Tomita T., Sohma Y., Mitsunuma H., Kanai M., Leuco Ethyl Violet as Self‐Activating Prodrug Photocatalyst for In Vivo Amyloid‐Selective Oxygenation. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2401346. 10.1002/advs.202401346

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.

References

- 1. Drew L., Nature. 2018, 559, S2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Glenner G. G., Wong C. W., Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1984, 120, 885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Masters C. L., Simms G., Weinman N. A., Multhaup G., McDonald B. L., Beyreuther K., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985, 82, 4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kondo J., Honda T., Mori H., Hamada Y., Miura R., Ogawara M., Ihara Y., Neuron. 1988, 1, 827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goedert M., Spillantini M. G., Jakes R., Rutherford D., Crowther R. A., Neuron. 1989, 3, 519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sevigny J., Chiao P., Bussiere T., Weinreb P. H., Williams L., Maier M., Dunstan R., Salloway S., Chen T., Ling Y., O'Gorman J., Qian F., Arastu M., Li M., Chollate S., Brennan M. S., Monzon O. Q., Scannevin R. H., Arnold H. M., Engber T., Rhodes K., Ferrero J., Hang Y., Mikulskis A., Grimm J., Hock C., Nitsch R. M., Sandrock A., Nature. 2016, 537, 50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dyck C. H. v., Swanson C. J., Aisen P., Bateman R. J., Chen C., Gee M., Kanekiyo M., Li D., Reyderman L., Cohen S., Froelich L., Katayama S., Sabbagh M., Vellas B., Watson D., Dhadda S., Irizarry M., Kramer L. D., Iwatsubo T., N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Suh J., Yoo S. H., Kim M. G., Jeong K., Ahn J. Y., Kim M., Chae P. S., Lee T. Y., Lee J., Lee J., Jang Y. A., Ko E. H., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 7064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ishida Y., Tanimoto S., Takahashi D., Toshima K., MedChemComm. 2010, 1, 212. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee B. I., Suh Y. S., Chung Y. J., Yu K., Park C. B., Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kwak J., Woo J., Park S., Lim M. H., J. Inorg. Biochem. 2023, 238, 112053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sohma Y., Sawazaki T., Kanai M., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 10017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kuang S., Zhu B., Zhang J., Yang F., Wu B., Ding W., Yang L., Shen S., Liang S. H., Mondal P., Kumar M., Tanzi R. E., Zhang C., Chao H., Ran C., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202312519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ran C., Pu K., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202314468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Du Z., Li M., Ren J., Qu X., Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang H., Yu D., Liu S., Liu C., Liu Z., Ren J., Qu X., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202109068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu Z., Deng Q., Qin G., Yang J., Zhang H., Ren J., Qu X., Chem. 2023, 9, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taniguchi A., Sasaki D., Shiohara A., Iwatsubo T., Tomita T., Sohma Y., Kanai M., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taniguchi A., Shimizu Y., Oisaki K., Sohma Y., Kanai M., Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nagashima N., Ozawa S., Furuta M., Oi M., Hori Y., Tomita T., Sohma Y., Kanai M., Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabc9750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matsukawa R., Yamane M., Kanai M., Chem. Rec. 2023, 23, e202300198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ozawa S., Hori Y., Shimizu Y., Taniguchi A., Suzuki T., Wang W., Chiu Y. W., Koike R., Yokoshima S., Fukuyama T., Takatori S., Sohma Y., Kanai M., Tomita T., Brain. 2021, 144, 1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rautio J., Kumpulainen H., Heimbach T., Oliyai R., Oh D., Järvinen T., Savolainen J., Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2008, 7, 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kanai M., Takeuchi Y., Tetrahedron. 2023, 131, 133227. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Urano Y., Kamiya M., Kanda K., Ueno T., Hirose K., Nagano T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 4888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kalluruttimmal R., Thattariyil D. T., Parambil A. P., Sen A. K., Chakkumkumarath L., Manheri M. K., Analyst. 2019, 144, 4210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wan W., Huang Y., Xia Q., Bai Y., Chen Y., Jin W., Wang M., Shen D., Lyu H., Tang Y., Dong X., Gao Z., Zhao Q., Zhang L., Liu Y., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 11335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lottman C., Grader G., Hazan Y. D., Melchior S., Avnir D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 8533. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heger D., Klánová J., Klán P. J., J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016, 110, 1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fukuzumi S., Ohkubo K., Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 561. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hari D. P., König B., Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 6688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li K., Lei W., Jiang G., Hou Y., Zhang B., Zhou Q., Wang X., Langmuir. 2014, 30, 14573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baba M., J. Phys. Chem. A. 2011, 115, 9514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen Y., Liu L., Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2012, 64, 640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Duxbury D. F., Chem. Rev. 1993, 93, 381. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Würthner F., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 14192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Amdursky N., Erez Y., Huppert D., Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wong H. E., Qi W., Choi H.‐M., Fernandez E. J., Kwon I., ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2011, 2, 645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jana M. K., Cappai R., Ciccotosto G. D., ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saleveson P. J., Haerianardakani S., Thuy‐Boun A., Yoo S., Kreutzer A. G., Demeler B., Nowick J. S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 5842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. How S.‐C., Hsu W.‐T., Tseng C.‐P., Lo C.‐H., Chou W.‐L., Wang S. S.‐S., J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2017, 36, 3420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ahsan N., Siddique I. A., Gupta S., Surolia A., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Salveson P. J., Haerianardakani S., Thuy‐Boun A., Yoo S., Kreutzer A. G., Demeler B., Nowick J. S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 11745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Würthner F., Kaise T. E., Saha‐Möller C. R., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Baptista M. S., Cadet J., Mascio P. D., Ghogare A. A., Greer A., Hamblin M. R., Lorente C., Nunez S. C., Ribeiro M. S., Thomas A. H., Vignoni M., Yoshimura T. M., Photochem. Photobiol. 2017, 93, 912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu M., Zhang Z., Cheetham J., Ren D., Zhou Z. S., Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 4940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Frisch M. J., Trucks G. W., Schlegel H. B., Scuseria G. E., Robb M. A., Cheeseman J. R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Petersson G. A., Nakatsuji H., Li X., Caricato M., Marenich A. V., Bloino J., Janesko B. G., Gomperts R., Mennucci B., Hratchian H. P., Ortiz J. V., Izmaylov A. F., Sonnemberg J. L., Williams‐Young D., Ding F., Lipparini F., Egidi F., Goings J., Peng B., Petrone A., Henderson T., Ranasinghe D., et al., Gaussian 16 Rev. C.01, Wallingford, CT: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shizu K., Kaji H., Commun. Chem. 2022, 5, 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lin J., Alexander‐Katz A., ACS Nano. 2013, 7, 10799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kim S., Dibildox A. M., Aguirre‐Soto A., Sikes H. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 11544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. We investigated the conversion of 2 to 3 under Hg lump irradiation (including λ = ca. 300 nm, which 2 absorbs), yet almost no 590 nm absorbance corresponding to 3 was detected. Therefore, photoexcitation of 2 would not promote the conversion from 2 to 3 .

- 52. Foote C. S., Fujimoto T. T., Chang Y. C., Tetrahedron Lett. 1972, 1, 45. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Boehme K., Brauer H. D., Inorg. Chem. 1992, 31, 3468. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pham D., Basu U., Pohorilets I., St Croix C. M., Watkins S. C., Koide K., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 17435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yamaguchi T., Takamura H., Matoba T., Terao J., Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1998, 62, 1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Capaldo L., Ravelli D., Fagnoni M., Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Saito T., Matsuba Y., Mihara N., Takano J., Nilsson P., Itohara S., Iwata N., Saido T. C., Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nilsberth C., Westlind‐Danielsson A., Eckman C. B., Condron M. M., Axelman K., Forsell C., Stenh C., Luthman J., Teplow D. B., Younkin S. G., Näslund J., Lannfelt L., Nat. Neurosci. 2001, 4, 887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yang Y., Arseni D., Zhang W., Huang M., Lövestam S., Schweighauser M., Kotecha A., Murzin A. G., Peak‐Chew S. Y., Macdonald J., Lavenir I., Garringer H. J., Gelpi E., Newell K. L., Kovacs G. G., Vidal R., Ghetti B., Ryskeldi‐Falcon B., Scheres S. H. W., Goedert M., Science. 2022, 375, 167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Umeda H., Sawazaki T., Furuta M., Suzuki T., Kawashima S. A., Mitsunuma H., Hori Y., Tomita T., Sohma Y., Kanai M., ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. For applications of 2 and 3 to other disease‐related amyloids, see Figure S31 (Supporting Information).

- 62. Ni J., Taniguchi A., Ozawa S., Hori Y., Kuninobu Y., Saito T., Saido T. C., Tomita T., Sohma Y., Kanai M., Chem. 2018, 4, 807. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supporting Information of this article.