Abstract

Question

This systematic review explores two questions: what parenting difficulties are experienced by mothers with borderline personality disorder (BPD); and what impact do these have on her children?

Study selection and analysis

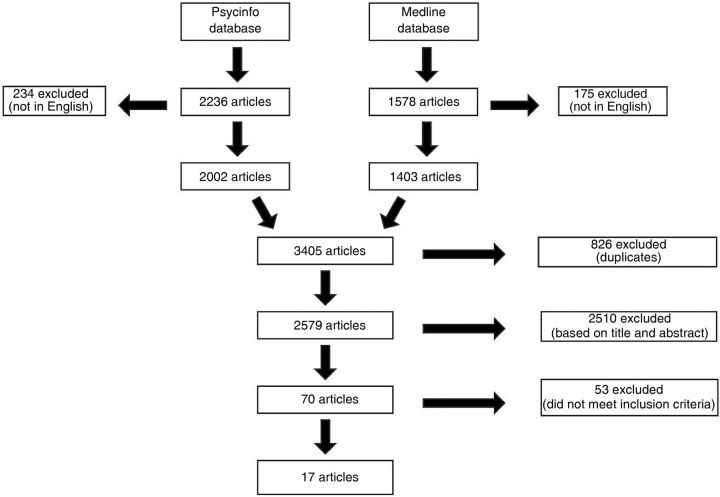

Studies had to include mothers with a diagnosis of BPD, who was the primary caregiver to a child/children under 19 years. PsycINFO and MEDLINE were screened (update: July 2014), yielding 17 relevant studies.

Findings

Mothers with BPD are often parenting in the context of significant additional risk factors, such as depression, substance use and low support. Interactions between mothers with BPD and their infants are at risk of low sensitivity and high intrusiveness, and mothers have difficulty in correctly identifying their emotional state. Levels of parenting stress are high, and self-reported competence and satisfaction are low. The family environment is often hostile and low in cohesion, and mothers with BPD show low levels of mind-mindedness but high levels of overprotection of older children. Outcomes for children are poor compared with both children of healthy mothers, and mothers with other disorders. Infants of mothers with BPD have poorer interactions with their mother (eg, less positive affect and vocalising, more dazed looks and looks away). Older children exhibit a range of cognitive–behavioural risk factors (eg, harm avoidance, dysfunctional attitudes and attributions), and have poorer relationships with their mothers. Unsurprisingly, given these findings, children of mothers with BPD have poorer mental health in a range of domains.

Conclusions

This review highlights the elevated need for support in these mother–child dyads.

Background

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) affects around 0.7–1% of the British population.1 Although there is much controversy over its definition and diagnosis, it is generally agreed to be characterised by difficulties in emotion regulation, and interpersonal relationships. Some individuals with BPD struggle with empathy, resulting in difficulties identifying and understanding others’ feelings. Relationships are often unstable and of high intensity, characterised by insecurity, hostility and lack of trust. They often exhibit chronic concerns about rejection and abandonment, most pronounced in close interpersonal relationships. Anxiety and depression are common in BPD, as are impulsivity and risk-taking.2

Individuals with BPD can also experience disturbances in their sense of identity, exhibiting unstable self-image, excessive self-criticism, and feelings of emptiness.2 Their self-presentation can fluctuate depending on the group or situation they are in, with the sufferer's sense of identity being experienced as dependent on a specific relationship.3

It is now widely accepted that mental health difficulties in parents impact on parenting and, subsequently, on outcomes for the child.4–7 However, despite the clear need for it, there is a paucity of research into the influences of parental BPD on parent as well as child. To the best of our knowledge, no attempt has been made at synthesis of the little that does exist. A better understanding of the impact of BPD on parenting and on children's outcomes might inform the development of interventions for this vulnerable group.

Objectives

Considering that BPD is most commonly diagnosed in women,8 many of whom will be mothers,9 the current review will draw together research considering maternal BPD. The aim is to systematically synthesise the findings of this research, in order to provide a better understanding of the consequences of maternal BPD.

Two questions are explored:

Are there deficits and difficulties in the parenting of mothers with BPD?

What difficulties are experienced by children of mothers with BPD?

Study selection and analysis

Searches were conducted on PsycINFO and MEDLINE.

The search string was: “child*” AND (“borderline personality disorder” OR “emotionally unstable personality disorder”). Figure 1 depicts the search process at the final date for checking: 10 July 2014.

Figure 1.

Search process.

Non-English language articles were removed, leaving 3405 articles. After removing duplicates, there remained 2579. In stage 1, titles and abstracts were read against inclusion/exclusion criteria by LP, and a random 10% were re-rated by an independent researcher. Agreement was 97.8%. Disagreements were resolved on discussion.

This resulted in removal of 2510 articles, leaving 70. At stage 2, each full paper was scrutinised against the inclusion/exclusion criteria (table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Type | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Sample | Mothers must have been diagnosed with BPD using standardised assessment procedures, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-II; First et al34), the Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines (DIB-R; Zanarini, et al35), the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (SIDP-IV; Pfohl et al36) or the Borderline Evaluation of Severity over Time (BEST; Pfohl et al37). Older studies using diagnostic techniques based on earlier editions of the DSM also acceptable | Diagnosis by any non-standardised assessment procedures |

| Mothers must be the primary caregiver to their child/children | Mothers not the primary caregiver to their children | |

| Mothers must be aged 18 or over | Mothers aged under 18 | |

| Children must be aged 18 or under | Children aged over 18 | |

| Procedure | Studies must measure factors influencing the mother's parenting and/or her child's functioning | Study does not measure these factors |

| Style | Studies must be written in English | Studies written in any other language |

| Studies must present outcome data | Study does not present unique outcome data (eg, reviews, commentaries, opinion pieces, books or chapters) | |

| Studies must be from peer-reviewed journals | Study is not peer-reviewed. Therefore, dissertations were excluded | |

| Studies must be quantitative in design | Case studies and qualitative papers were excluded |

BPD, borderline personality disorder; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Consequently, 54 papers were excluded (the reasons are summarised in table 2).

Table 2.

Reasons for exclusion following full-text examination

| Reason for exclusion | Number excluded |

|---|---|

| Non-peer-reviewed studies, or reviews or commentary pieces | 19 |

| Investigated the parents or siblings of individuals with BPD (but not offspring) | 11 |

| Investigated several different personality disorders, and did not present specific results for those with BPD | 7 |

| Investigated mothers with BPD, or their children, but did not examine parenting or children's outcomes | 7 |

| Only measured borderline features, no diagnosis of BPD | 5 |

| Children were aged over 18 | 3 |

| Case studies | 2 |

BPD, borderline personality disorder.

This left 17 papers that satisfied the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Reference lists were scrutinised for titles relevant to the review. This revealed no further papers.

Eight prominent authors were contacted, and asked to identify any additional studies, but none were found.

Quality appraisal

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist10 is widely accepted as a tool for improving the quality of reporting of observational studies.11 The cross-sectional variant lists 22 areas that are required for highest quality reporting of cross-sectional research. For this review, each area was rated on a five-point scale, and scores averaged to provide a total score. Four papers were categorised as ‘average to above average’, and 13 as ‘above average to good’ (terms based on the Jadad scale,12 which ranges from 0 (bad) to 5 (good); table 3).

Table 3.

Five-point rating system developed to score the STROBE checklist

| Rating | Explanation |

|---|---|

| 1 | Weak, main points missing, with little thought or consideration given to important factors |

| 2 | Below average, with some but not all main points included, some information still missing |

| 3 | Average, acceptable amount of information on main areas given, but additional relevant information that would have made the section stronger is missing |

| 4 | Above average, all main areas considered and discussed in depth, with a few pieces of less important information missing |

| 5 | Good, all areas carefully considered and discussed, very little missing |

Five randomly selected articles were re-scored by an independent rater. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using Spearman’s correlation, giving a strong, positive correlation between quality ratings, rs=0.95, n=5, p=0.014. The primary researcher’s ratings were, therefore, accepted.

Findings

Maternal BPD and parenting

Fourteen studies assessed parenting (table 4). Across the age range, these studies showed that mothers with BPD were parenting in the context of many factors that are known to put parenting and children's mental health at risk. All studies that explored parental depression showed this to be significantly elevated in mothers with BPD, compared with a range of control groups.13–16 Feldman et al17 noted higher drug and alcohol abuse in parents with BPD (present in 88%), and White et al18 noted that their sample of parents with BPD used more alcohol during pregnancy.

Table 4.

Summary of studies investigating the impact of maternal BPD on parenting, and on children

| Study (children's ages) | Number of mothers | Number of children | How BPD in the mother was diagnosed | Measures | Quality rating out of 5 | Summary of findings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With BPD | Healthy controls | With other disorders | Of mothers with BPD | Of healthy control mothers | Of mothers with other disorders | |||||

| Abela et al32 (6–14 years) | – | – | – | 20 | – | 120 from mothers with MDD | SCID-II | Verbal interviews, K-SADS, CASQ, CRSQ, SEQ, CDAS-R, CDEQ, IPPA and RSSC | 3.6 | Parental BPD was significantly related to children having more depressive symptoms, negative attributional style, dysfunctional attitudes, insecure attachment style, and excessive reassurance seeking. 45% of these children had experienced a major depressive episode |

| Barnow et al19 (11–18 years) | 16 | 116 | 36 mothers with depression 28 mothers with other personality disorders |

23 | 156 | 47 from mothers with depression, 31 from mothers with Cluster C PDs | SCID-II | Diagnostic Expert System for Psychiatric Disorders, SSAGA, and the Children Diagnostic Interview for Psychiatric Disorder. All given the CBCL, TCI, EMBU, YSR, and the Rosenberg Self-Worth Scale. Mothers interviewed using the Diagnostic Expert System for Psychiatric Disorders, and SSAGA | 4 | More comorbidity in the mothers with BPD. Described by their children as being overprotective. Children whose mothers had BPD had higher harm avoidance, more attention problems, more delinquency and aggression, social problems, and more self-ratings of depression, anxiety, emotional problems, suicidal tendencies and lower self-esteem |

| Crandell et al20 (2 months) | 8 | 12 | – | 8 | 12 | – | Completion of the questionnaire and full interview section of the SCID-II | Interactions between mother and baby rated using the global ratings for mother–infant interactions (Murray et al38) | 4 | Mothers with BPD relate to their infants in an intrusively insensitive manner, and their mother–infant interactions were scored as less satisfying by an objective rater. During the mother's non-response stage, infants of mothers with BPD had more dazed looks. After this stage, they showed less positive affect |

| Crittenden and Newman15 (3–36 months) | 15 | 17 | – | – | – | – | DIB-R | AAI, Working Model of the Child Interview | 3.8 | Mothers with BPD reported higher levels of depression and parenting stress |

| Delavenne et al25 (3 months) | 17 | 17 | – | 17 | 17 | – | SIDP-IV | Used vocal recordings of interactions and used software to define interactional phrases | 3.8 | Mothers with BPD had more fragmented interactions with their infants, characterised by longer pauses, fewer interactional phrases, and more non-vocal sounds to fill gaps. Infants of mothers with BPD vocalised less than control infants. Their vocalisations were also shorter |

| Elliot et al26 (3–14 months) | 13 | 13 | – | 13 | 13 | – | Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder | EPDS, BDI, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, CTQ, DERS, ECRS, PSI-SF, and PACOTIS | 4 | Mothers with BPD were less accurate when identifying emotions in infants. Higher scores for depression, total emotional dysregulation, and parenting stress. Lower perception of their own parenting competence |

| Feldman et al17 (4+. Mean age approx. 11 years) | 9 | – | 14 mothers with other personality disorders | 21 | – | 23 from mothers with other personality disorders | DIB-R | FTRI, FES, and FSS | 3.8 | Mothers with BPD scored significantly lower than control mothers on measures of cohesion and organisation, and had lower satisfaction with their families. Children of mothers with BPD were exposed to more parental suicide attempts and reported low levels of familial satisfaction, independence and expressiveness |

| Gratz et al14 (12–23 months) | 23 | 78 | – | 23 | 78 | – | DIB-R, BEST | Infant behaviours and the strange situation scenario were videotaped and coded using the AFFEX coding system, alongside using DERS, AIM, DASS | 4.4 | More depressive symptoms in mothers with BPD. Higher levels of maternal intensity and reactivity, found in those with BPD, were linked with lower self-focused emotion regulation, blunted fear and more anger in their infants |

| Herr et al29 (15 years) | 70 | 461 | 354 with either MDD, Depressive Disorder, or both | 70 | 461 | 354 from mothers with either MDD, Depressive Disorder, or both | SCID-II | KSADS-E, BDI, YCS, SPPA, Teacher Report of Youth Interpersonal Functioning, Bartholomew Attachment Prototypes Questionnaire, PPQ | 4.2 | Children of mothers with BPD found it hard to make friends and be socially accepted. Also had more fearful attachment cognitions. Rated their mothers as more likely to be hostile |

| Hobson et al21 (12 months) | 10 | 22 | – | 10 | 22 | – | SCID-II | Rated interactions using the global ratings for mother-infant interactions (Murray et al, 1996) | 4.4 | Mothers with BPD were found to be more intrusively insensitive. Infants whose mothers had BPD displayed less availability for positive engagement, lower behavioural organisation and mood state, and they gave fewer positive looks to a stranger |

| Hobson et al23 (Unclear. Circa 1–2 years; average age 69 weeks) | 13 | 31 | 15 mothers with depression | 13 | 31 | 15 from mothers with depression | SCID-II | AMBIANCE | 4 | Mothers with BPD were more likely to have disrupted affective communication with their infants. Showed more disorientation and fear during infants’ attachment bids |

| Kiel et al22 (12–23 months) | 22 | 77 | – | 22 | 77 | – | BEST | DERS, DASS, maternal affective and behavioural expressions were coded | 4 | Mothers with BPD had more emotion dysregulation. Took longer time to display positive affect in response to infant distress. Mothers with BPD were more likely to respond insensitively when infant distress continued |

| Macfie and Swan31 (4–7 years) | – | – | – | 30 | 30 | – | SCID-II | PPVT-III, ASCT, the MacArthur Story Stem Battery, coded using the same systems as Macfie et al39 | 4.4 | Children of mothers with BPD expressed more fear of abandonment, role reversal and more negative expectations of parent–child relationships in a role-play situation. More likely to represent themselves as incongruent and shameful. More confusion between fantasy and reality |

| Newman et al13 (mean 16 months) | 14 | 20 | – | 14 | 20 | – | Independent clinical diagnosis of BPD, meeting DSM-IV criteria for BPD, and DIB-R | Video interactions coded using EA scales | 4 | Mothers with BPD scored significantly higher on all SCL-90R psychopathology indices and on the EPDS. Mothers with BPD were less sensitive, and reported less satisfaction and more incompetence in their parenting. Infants whose mothers had BPD were less responsive to the mother, and less eager to engage with her |

| Schacht et al16 (39–61 months) | 20 | 19 | – | 20 | 19 | – | Mothers needed to attract a BPD diagnosis on at least one of two administrations of SCID-II | Mothers given BDI, Meins and Fernyhough's (2010) brief interview measure for mind-mindedness. Children given SCQ, BPVS-II, false-belief tasks, affective-labelling task, and a modified version of the causes of emotions interview | 4.2 | Mothers with BPD were more likely to report depressive symptoms. They also used significantly fewer mind-related comments to describe their children. Children of mothers with BPD struggled to identify and describe causes of emotion, and had less understanding of mental states, doing less well in the Theory of Mind tasks |

| Weiss et al33 (4+. Mean approximately 11 years) | 9 | – | 14 mothers with other personality disorders | 21 | – | 23 from mothers with other personality disorders | DIB-R | FTRI, KSADS-E, CGAS and CDIB | 4 | Children of mothers with BPD had significantly more general psychopathology. Both groups had history of trauma |

| White et al18 (c. 3 months) | 17 | 25 | 25 mothers with MDD and 20 mothers with BPD comorbid with MDD | 17 | 25 | 25 from mothers with MDD, 20 from mothers with comorbid MDD and BPD | SCID-IV and DIB-R | BDI and BAI. Videotaped interactions coded using the Interaction Rating Scale. Children given the IBQ-R | 4.2 | Women with BPD, and those with comorbid MDD, consumed more alcohol during pregnancy than healthy controls. Smiled less at their infants than healthy controls. Mothers with BPD also touched their infants less, played fewer games with them, and imitated them less. Infants of mothers with BPD had higher levels of fear, were less soothable, and were classed as having higher environmental risk. Less frequent smiling and vocalisation |

AAI, Adult Attachment Interview; AFFEX, System for Identifying Affect Expression by Holistic Judgement; AIM, Affect Intensity Measure; AMBIANCE, Atypical Maternal Behaviour Instrument for Assessment and Classification; ASCT, Attachment Story Completion Task; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BEST, Borderline Evaluation of Severity over Time; BPD, borderline personality disorder; BPVS-II, British Picture Vocabulary Scale II; CASQ, Children's Attributional Style Questionnaire; CBCL, Child Behaviour Checklist; CDAS-R, Children's Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale-Revised; CDEQ, Children's Depressive Experiences Questionnaire; CDIB, Child Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines; CGAS, Child Global Assessment Schedule; CRSQ, Children's Response Style Questionnaire; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; DASS, Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales; DERS, Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; DIB-R, Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; EA, Emotional Availability Scales; ECRS, Experiences in Close Relationships Scale; EMBU, Swedish acronym for Own Memories Concerning Upbringing; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; FES, Family Environment Scale; FSS, Family Satisfaction Scale; FTRI, Family Trauma and Resilience Interview; IBQ-R, Infant Behaviour Questionnaire, Revised; IPPA, Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment; K-SADS, Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children; KSADS-E, Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Episodic Version; MMD, major depressive disorder; PACOTIS, Parental Cognitions and Conduct Toward the Infant Scale; PPQ, Perceived Parenting Quality Questionnaire; PD, personality disorder; PPVT-III, Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Third Edition; PSI-SF, Parenting Stress Index Short Form; RSSC, Reassurance-Seeking Scale for Children; SCID-II, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist 90 Revised; SCQ, Social Communication Questionnaire; SEQ, Children's Self-Esteem Questionnaire; SIDP-IV, Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality; SPPA, Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents; SSAGA, Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism; TCI, Temperament and Character Inventory; YCS, Youth Chronic Stress Interview; YSR, Youth Self-Report.

Some studies15 19 noted that mothers with BPD were more likely than control groups to be parenting without the support of a partner, or within a household that frequently changed in its composition.17 This study also noted that children of BPD parents had experienced more changes in school, and more non-maternal care than controls.

Parental mental health also made its impact felt in other ways: Feldman et al17 showed that children of parents with BPD were at risk of witnessing parental suicide attempts, with 24% of the sample (mean age 11 years) having witnessed a maternal attempt, and 19% having witnessed a paternal attempt.

The impacts of BPD on parenting are now presented by age of child: babies and young children; older children.

Babies and young children

Parenting in the context of BPD is not well understood, but perhaps the greatest attention has been devoted to the newborn and toddler age group. All studies of this age group conclude that mothers with BPD parent differently, on average, to a range of control samples.

Interaction style

White et al18 studied mothers with BPD, major depressive disorder (MDD) and healthy controls, in interaction with their 3-month-old infants. Mothers with BPD smiled less, touched and imitated their infants less and played fewer games with their babies. Lack of sensitivity in interactions with offspring is a recurring theme. Crandell et al20 observed mothers of 2-month-old infants in face-to-face interaction with their child. Compared with healthy controls, mothers with BPD were less sensitive in their interactions, and more intrusive. Observers subsequently rated their interactions as less ‘satisfying’ and ‘engaged’. Similarly, Newman et al13 rated mothers with BPD of 16-month-olds as less sensitive than healthy controls, and Hobson et al21 also found their mothers with BPD to be more ‘intrusively insensitive’ in their interactions with their 1-year-olds, compared with healthy controls, and these differences remained once demographic differences between the groups were controlled. Kiel et al22 found that, in comparison with healthy control mothers, mothers with BPD showed less positive affect in response to infant distress, and took longer to do so. As infant distress increased in duration, mothers with BPD were increasingly likely to show insensitive behaviour towards their child. These differences remained even when group differences in anxiety and depression were controlled. Hobson et al23 also explored affective communication, this time in mothers with BPD of toddlers. This was found to be disrupted, in comparison to a healthy control group and a depressed control group. Mothers with BPD were also more likely to exhibit a ‘fear/disorientation’ response to their child's attachment bids, a pattern that has been linked to disorganised attachment in the child.24 Finally, musicologists recorded interactions between mothers and their 3-month-old infants.25 They found that, in comparison with healthy controls, interactions where the mother had BPD differed in ‘temporal qualities and musical organisation’. Mothers with BPD paused longer and used more non-vocal sounds than controls.

Emotion recognition

Ability to identify infants’ emotions was disrupted in BPD mothers of children aged 3–14 months.26 Compared with healthy controls, mothers with BPD were less accurate at identifying emotions in photographs of their own and unfamiliar children. In particular, they were prone to labelling neutral expressions as ‘sad’. This sample of mothers was also likely to self-report overprotection of their child.

Activity structuring

On a pragmatic level, mothers with BPD were found to be less good at structuring their children's activities, in comparison with healthy controls.27

Parenting stress/self-competence

Unsurprisingly, given the results described above, mothers with BPD, of children in this age group have been shown to self-report higher parenting stress,15 26 lower competence,27 26 and lower satisfaction in the parenting role13 than control parents.

Older children

Family environment

Using the Family Environment Scale,28 Feldman et al17 showed that mothers with BPD rated their family as lower in cohesion and organisation, and higher on conflict than the control group, which comprised mothers with other types of personality disorder. Children in this study (mean 11 years) were also more likely to rate their family as low in cohesion and expressiveness if their parent was diagnosed with BPD as opposed to another personality disorder. Similarly, Herr et al29 found that BPD symptoms in mothers were correlated with ratings of maternal hostility given by their 15-year-old offspring. Feldman et al17 concurred, finding that verbal abuse, physical abuse and witnessing of violence were common in their sample of children of mothers with BPD, even in comparison with children whose parents had other personality disorders.

Mind-mindedness

Schacht et al16 explored mind-mindedness (parental ability and willingness to think about their child's mental state30 in parents of children aged 39–61 months). They found evidence of reduced mind-mindedness in interviews with mothers with BPD, in comparison with healthy controls, a difference that remained once maternal depression was controlled.

Overprotection

Two studies found that mothers with BPD scored higher on a measure of overprotection of children. Children (mean age 11 years) of mothers with BPD rated their mothers as less encouraging of independence than children whose mothers had other personality disorders.17 Similarly, mothers with BPD were reported to be more overprotective by their children aged 11–18 years, in comparison with healthy controls and controls with depressive illness and other personality disorders.19 It should be noted, however, that children of mothers with BPD might be living in environments that are more risky than average children, and that this higher reported overprotection might be advantageous in these conditions.

Parenting stress/satisfaction

Finally, given the differences in parenting reported above, it is not surprising that Herr et al29 noted chronic stress in the relationship between mothers with high levels of BPD symptomatology and their 15-year-old offspring, and Feldman et al found extremely low self-reported satisfaction with their family (at the 1st centile) in mothers with BPD.19

Influence of maternal BPD on children's outcomes

Twelve papers measured the association between maternal BPD and child outcomes (see table 4). As above, the outcomes are reported separately for babies/toddlers and for older children.

Babies/toddlers

Across five studies, babies/toddlers of mothers with BPD behaved differently to those of control mothers. Crandell et al20 found that when exposed to a 90 s ‘still-face’ challenge, 2-month-old infants of mothers with BPD were more likely to look away, or to look dazed than children of healthy controls. In a standard face-to-face interaction with their mother, children of mothers with BPD showed less positive affect, and again, more dazed looks. In similar studies of face-to-face interactions between mothers and their infant children, children of mothers with BPD were shown to smile less,18 vocalise less,18 25 avert their gaze more, appear more fearful and be less soothable,18 be less responsive to mothers’ bids for interaction, and show less optimally ‘involving’ behaviours towards their mothers than control mothers.27 They also displayed lower ‘availability for positive engagement’ with and fewer positive looks towards a stranger, and had lower ‘behavioural organisation’ and mood state.21

Older children

Cognitive and behavioural risk factors

Older children of parents with BPD showed a range of cognitive and behavioural risk factors in comparison with control children. Herr et al29 found that maternal BPD symptoms were negatively correlated with Harter social acceptance scores, and ability to make close friends in their 15-year-old sample, and that this relationship held even after maternal depression was controlled. Schacht et al16 found that preschool-aged children of women with BPD had poorer theory of mind when given a false-belief task, and were poorer at both labelling pictures of emotional faces and identifying possible causes of the depicted emotions. Macfie and Swan31 found that their children aged 4–7 years of mothers with BPD displayed more negative self-representations, more fantasy-proneness and fantasy-reality confusion, lower narrative coherence and more intrusion of traumatic material when participating in a series of role-play scenarios, when compared with children of healthy mothers. Abela et al32 found their children aged 6–14 years of mothers with BPD to have a more negative attribution style, more dysfunctional attitudes, a more ruminative response style, engage in more reassurance-seeking, and have higher levels of self-criticism than a sample of children of depressed mothers. Finally, in the study by Barnow et al,19 children (aged 11–18 years) showed excessive harm-avoidance, in comparison with children of depressed mothers and healthy mothers.

Parent–child relationships

As well as these elevated cognitive and behavioural risk factors, children seem to have a higher risk of problematic relationships with their parents with BPD. Four studies showed that children of mothers with BPD had elevated instances of disrupted attachment styles.21 29 31 32 Additionally, in role-play tasks, children of mothers with BPD (aged 4–7 years) showed excessive role-reversal,31 and fear of abandonment in their relationships with their parents, and more negative expectations of these relationships. Interestingly, Gratz et al14 reported that although there was no direct relationship between maternal BPD symptoms and infant emotion regulation in their sample, there was an indirect relationship, which was mediated by maternal emotional dysfunction, and that this was particularly the case for the large proportion of children in their sample who were classified as having an insecure-resistant attachment style.

Mental health outcomes

In almost all instances where mental health outcomes were explored, children of parents with BPD fared worse than control children, even when these control children had parents with significant mental health difficulties, for example, Weiss et al33 found that children of mothers with BPD (mean age around 11 years) had lower Child Global Assessment Schedule (CGAS) scores than children of mothers with other personality disorders, and that the mean of these scores was in the ‘non-functional’ range. The one exception was the study by Abela et al,32 which did not find increased difficulties with self-esteem or dependency in children aged 6–14 years of mothers with BPD, compared with children of depressed mothers. It should be noted that lack of power (there were only 20 mothers with BPD) in this study could have accounted for this null finding.

Three studies that explored symptoms of emotional disorders found that these were higher in children of parents with BPD compared with control groups: Barnow et al compared children aged 11–18 years of mothers with BPD with children of mothers with depression, and mothers with other personality disorders, and found the children of mothers with BPD to have signs of higher levels of emotional disorder and of suicidal ideation.21 Indeed, 9% of children whose mothers had BPD had already attempted suicide, compared with 2% of children of healthy mothers. Abela et al32 studied children aged 6–14 years and found that those with a mother with BPD had experienced more depression (45% had suffered a major depressive episode), than a sample of children whose mothers were currently depressed. This study explored a number of potential cognitive and behavioural risk factors in children (see above) and found that these partly mediated the relationship between maternal BPD and children's depression. Finally, Herr et al29 found that symptoms of BPD in mothers were positively associated with depression in their 15-year-old youth, although in this instance, this relationship disappeared when maternal depression was controlled.

Two studies explored the relationship between maternal BPD and children's externalising symptoms. In both cases, there was a positive association. Weiss et al33 reported that children (with a mean age of 11) whose mother had BPD, were more likely to have a behavioural disorder or attention deficit disorder than the children in the control group, whose parents had a range of other personality disorders (but not BPD). Barnow et al19 also found more parent-reported symptoms of (11–18 years old) children's behavioural problems in their sample of mothers with BPD, in comparison with children of healthy controls.

Conclusions and clinical implications

In studies employing a range of designs and comparison groups, and all of reasonable quality, mothers’ BPD diagnosis was clearly associated with differences in parenting. In the studies of early childhood, most of which focussed on mother–child interactions, maternal BPD was associated with reduced sensitivity and increased intrusivity towards the child.13 20–22 This is, perhaps, not surprising, given the finding that mothers with BPD found it difficult to correctly identify emotions in photographs of both their own and strangers’ children.26 Mothers with BPD also found it more difficult to structure their young child's activities,13 and in later childhood were rated as having poorer levels of family organisation.17 The family environment where mothers had BPD was characterised by high levels of hostility,17 29 and low levels of cohesion,17 according to both parent and child reportings. Mothers with BPD were reported to show high levels of overprotection towards their children17 19 but to have lower levels of mind-mindedness,16 that is, a reduced ability to reflect on their child's internal world.

Given these difficulties in parenting experienced by mothers with BPD, it is perhaps unsurprising that they reported feeling less competence13 26 and satisfaction27 17 in the parenting role. In a number of studies, they also found parenting to be a very stressful task.15 26 29

The children of mothers with BPD experience a range of negative outcomes. In infancy, they appear to experience interactions with their mother as less satisfying,20 showing signs of less positive affect,18 20 21 more looking away,18 20 more dazed looks20 and fewer vocalisations.18 25 Subsequently, these children experience a range of cognitive–behavioural risk factors. Compared with control children, they had more difficulties with friendships,29 poorer theory of mind,16 difficulties labelling and understanding the causes of common emotions,16 increased fantasy proneness and difficulty distinguishing fantasy and reality,31 increased negative attributional style, dysfunctional attitudes, rumination and self-criticism.32 They also experience difficulties in the mother–child relationship, with four studies reporting high levels of disrupted attachment styles,21 29 31 32 and in role-play scenarios elevated levels of role-reversal with parents, fear of abandonment, and negative expectations of parents.31 These factors are known to put children at risk of poor mental health outcomes, and indeed, this appears to be the case. Children of mothers with BPD had poorer mental health than control groups, showing substantially elevated levels of depression,19 29 32 suicidality,19 fearfulness,18 29 behaviour problems19 33 and attention deficit disorder.33

Most notably, many studies included parents with other diagnoses as control groups, typically other severe presentations, such as MDD and other personality disorders. In most instances, mothers with BPD (and their children) had greater difficult and poorer outcomes than any of these groups, underscoring the particularly severe difficulties that are faced by these mothers and their children.

But, can a causal relationship between BPD and impaired parenting, and subsequently between parenting and child outcome be assumed? Given the difficult circumstances in which mothers with BPD are often parenting (increased likelihood of lone-parenting,15 19 depression,13–16 26 substance misuse,17 18 we must consider the possibility that it is these factors, rather than BPD that cause the poor outcomes for their children. However, many of the studies reported here controlled for maternal depression and/or demographic factors, and in almost every instance, the relationship between BPD and impaired parenting, or BPD and child outcomes, was upheld. Unfortunately, few studies have examined both parenting risks and child outcomes, and explored the mediating role of the former. However, in the handful of studies that did this, it was apparent that the relationship between parent and child mental health was mediated by parenting difficulties.

The current systematic review is subject to some limitations. First, owing to a lack of resource for translation, it excluded all papers that were not in English. Second, although all studies were deemed to be of a reasonable standard, all were subject to some risk of bias. In particular, all were cross-sectional in design, which limits the conclusions that may be drawn. Similarly, although all studies made some attempt to confirm a diagnosis of BPD in participants, in some cases,14 22 29 this was achieved only by means of self-report questionnaire measures, which is not an optimally valid approach. Similarly, parents were often the primary reporter on children's outcomes, which is likely to have introduced a bias. Almost all the studies were very small (see table 4), meaning that they were probably underpowered to detect smaller group differences (although it should be noted that most studies found significance between groups on almost all their outcome measures). However, the very small samples of mothers with BPD that were present in most of the studies will have had an impact on generalisability of the findings. The risk of publication bias is probably quite high, given the small sample sizes in the field, and the consequent lack of power likely in many studies. Finally, it is not clear whether the studies reported here employed samples that are highly representative of the diverse population of mothers with BPD. Most employed clinical samples, which is likely to be over-representative of the severe end of the disorder. It should be noted that all these studies represent the ‘average’ parent with BPD, and it is likely that many such parents actually manage very well and have children with good outcomes.

The findings of this review show how very difficult parenting is for mothers with a diagnosis of BPD. These difficulties are probably more severe than for families where a parent has MDD or another personality disorder. Furthermore, it seems likely that if these mothers are not supported in the parenting role, their children are at risk for a range of poor outcomes. While interventions exist for women with BPD,9 there are currently no interventions that aim to reduce the risk to their children. These families do not deserve to be as overlooked as they have been, as there is evidence, even though it is limited, that they are in particular need of help.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: This report is independent research arising from an NIHR Career Development Award supported by the National Institute for Health Research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research of the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Coid J, Yang M, Tyrer P, et al. Prevalence and correlates of personality disorder in Great Britain. Br J Psychiatry 2006;188:423–31. 10.1192/bjp.188.5.423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edn. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson-Ryan T, Westen D. Identity disturbance in borderline personality disorder: an empirical investigation. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:528–41. 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg-Nielsen TS, Vikan A, Dahl AA. Parenting related to child and parental psychopathology: a descriptive review of the literature. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2002;7:1045–359. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nomura Y, Wickramaratne PJ, Warner V, et al. Family discord, parental depression, and psychopathology in offspring: ten-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2002;41:402–9. 10.1097/00004583-200204000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohannessian CM, Hesselbrock VM, Kramer J, et al. The relationship between parental psychopathology and adolescent psychopathology: an examination of gender patterns. J Emot Behav Disord 2005;13:67–76. 10.1177/10634266050130020101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vostanis P, Graves A, Meltzer H, et al. Relationship between parental psychopathology, parenting strategies and child mental health--findings from the GB national study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2006;41:509–14. 10.1007/s00127-006-0061-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gunderson JG. Borderline personality disorder, second edition: a clinical guide. American Psychiatric Pub, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stepp SD, Whalen DJ, Pilkonis PA, et al. Children of mothers with borderline personality disorder: identifying parenting behaviors as potential targets for intervention. Personal Disord 2012;3:76–91. 10.1037/a0023081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology [STROBE] statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Gac Sanit 2008;22:144–50. 10.1157/13119325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bolignano D, Mattace-Raso F, Torino C, et al. The quality of reporting in clinical research: the CONSORT and STROBE initiatives. Aging Clin Exp Res 2013;25:9–15. 10.1007/s40520-013-0007-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1–12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newman LK, Ste CS, Bergman LR, et al. Borderline personality disorder, mother-infant interaction and parenting perceptions: preliminary findings. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2007;41:598–605. 10.1080/00048670701392833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gratz KL, Kiel EJ, Latzman RD, et al. Emotion: empirical contribution. Maternal borderline personality pathology and infant emotion regulation: examining the influence of maternal emotion-related difficulties and infant attachment. J Pers Disord 2014;28:52–69. 10.1521/pedi.2014.28.1.52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crittenden PM, Newman L. Comparing models of borderline personality disorder: mothers’ experience, self-protective strategies, and dispositional representations. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010;15:433–51. 10.1177/1359104510368209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schacht R, Hammond L, Marks M. The relation between mind-mindedness in mothers with borderline personality disorder and mental state understanding in their children. Infant Child Dev 2013;22(July 2012):68–84. 10.1002/icd.1766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldman RB, Zelkowitz P, Weiss M, et al. A comparison of the families of mothers with borderline and nonborderline personality disorders. Compr Psychiatry 1995;36:157–63. 10.1016/S0010-440X(95)90110-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White H, Flanagan TJ, Martin A, et al. Mother–infant interactions in women with borderline personality disorder, major depressive disorder, their co-occurrence, and healthy controls. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2011;29:223–35. 10.1080/02646838.2011.576425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnow S, Spitzer C, Grabe HJ, et al. Individual characteristics, familial experience, and psychopathology in children of mothers with borderline personality disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006;45:965–72. 10.1097/01.chi.0000222790.41853.b9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crandell LE, Patrick MPH, Hobson RP. ‘Still-face’ interactions between mothers with borderline personality disorder and their 2-month-old infants. Br J Psychiatry 2003;239–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hobson RP, Patrick M, Crandell L, et al. Personal relatedness and attachment in infants of mothers with borderline personality disorder. Dev Psychopathol 2005;17:329–47. 10.1017/S0954579405050169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiel EJ, Gratz KL, Moore SA, et al. The impact of borderline personality pathology on mothers’ responses to infant distress. J Fam Psychol 2011;25:907–18. 10.1037/a0025474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hobson RP, Patrick MPH, Hobson JA, et al. How mothers with borderline personality disorder relate to their year-old infants. Br J Psychiatry 2009;195:325–30. 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.060624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abrams KY, Rifkin A, Hesse E. Examining the role of parental frightened/frightening subtypes in predicting disorganized attachment within a brief observational procedure. Dev Psychopathol 2006;18:345–61. 10.1017/S0954579406060184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delavenne A, Gratier M, Devouche E, et al. Phrasing and fragmented time in “pathological” mother-infant vocal interaction. Music Sci 2008;12(Suppl 1):47–70. 10.1177/1029864908012001031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elliot R, Hunter M, Cooper G, et al. When I look into my baby's eyes…infant emotion recognition by mothers with borderline personality disorder. Infant Ment Health J 2014;35:21–32. 10.1002/imhj.21426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Newman L, Stevenson C. Issues in infant–parent psychotherapy for mothers with borderline personality disorder. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2008;13:505–14. 10.1177/1359104508096766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moos BS. Family environment scale manual. Consulting Psychologists Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herr NR, Hammen C, Brennan PA. Maternal borderline personality disorder symptoms and adolescent psychosocial functioning. J Pers Disord 2008;22: 451–65. 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.5.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meins E. Security of attachment and the social development of cognition. Psychology Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macfie J, Swan SA. Representations of the caregiver-child relationship and of the self, and emotion regulation in the narratives of young children whose mothers have borderline personality disorder. Dev Psychopathol 2009;21:993–1011. 10.1017/S0954579409000534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abela JRZ, Skitch SA, Auerbach RP, et al. The impact of parental borderline personality disorder on vulnerability to depression in children of affectively ill parents. J Pers Disord 2005;19:68–83. 10.1521/pedi.19.1.68.62177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss M, Zelkowitz P, Feldman RB, et al. Psychopathology in offspring of mothers with borderline personality disorder: a pilot study. Can J Psychiatry 1996;41:285–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R personality disorders (SCID-II). Part I: Description. J Pers Disord 1995;9:83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenburg FR, et al. The revised diagnostic interview for borderlines: discriminating BPD from other axis II disorders. J Pers Disord 1989;3:10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality: SIDP-IV. American Psychiatric Pub. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfohl B, Blum N, John DS, et al. Reliability and validity of the Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST): a self-rated scale to measure severity and change in persons with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 2009;23:281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murray L, Fiori-Cowley A, Hooper R, et al. The impact of postnatal depression and associated adversity on early mother -infant interactions and later infant outcome. Child Dev 1996;67:2512–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macfie J, Swan SA, Fitzpatrick KL, et al. Mothers with borderline personality and their young children: Adult Attachment Interviews, mother -child interactions, and children's narrative representations. Dev Psychopathol 2014;26:539–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]