Abstract

Background

High throughput technologies provide new opportunities to further investigate the pathophysiology of ischemic strokes. The present cross‐sectional study aimed to evaluate potential associations between the etiologic subtypes of ischemic stroke and blood‐based proteins.

Methods

We investigated the associations between ischemic stroke subtypes and a panel of circulating inflammation biomarkers in 364 patients included in the Stroke Cohort Augsburg (SCHANA). Stroke etiologies were categorized according to the TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) classification. Serum concentrations of 52 biomarkers were measured using the Bio‐Plex Pro™ Human Cytokine Screening Panel, ICAM‐1 set and VCAM‐1 set, plus the Pro™ Human TH17 cytokine sCD40L set and IL31 set (all Bio‐Rad, USA). Multivariable linear regression models were used to examine associations. Point estimates were calculated as the mean difference in ‐standardized cytokine levels on the log2‐scale.

Results

Stromal‐cell‐derived‐factor 1 alpha (SDF‐1a) showed significantly higher serum levels in cardioembolic compared with large vessel atherosclerotic stroke (β = 0.48; 95% CI 0.22; 0.75; P adj = 0.036). Significantly lower levels of interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) (β = −0.53; 95% CI −0.84; −0.23; P adj = 0.036) and macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) (β = −0.52; 95% CI −0.84; −0.21; P adj = 0.043) were found in the small vessel versus large vessel stroke subtype.

Conclusions

Immune dysregulations observed in different stroke subtypes might help uncover pathophysiological mechanisms of the disease. Further studies are needed to validate identified biomarkers in diverse study populations before they can potentially be used in clinical practice to further improve stroke management and patient outcomes.

Keywords: biomarker, inflammation, pathophysiology, stroke, TOAST classification

INTRODUCTION

In industrialized countries, stroke is the third leading cause of death and the most widespread cause of long‐term disability. Ischemic stroke is the most common form of all strokes, accounting for approximately 87% of all cases [1]. Whenever possible, acute stroke therapy consists of recanalization of the occluded artery by administration of intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (tPA). In the case of occlusion of larger intracranial vessels, this therapy needs to be combined with endovascular mechanical thrombectomy [2].

The etiology of ischemic stroke is usually classified according to the TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) classification [3] into large artery atherosclerosis (20%), cardioembolism (20%), small vessel occlusion (20%), other (5%) determined causes (e.g., dissection, mitochondrial or genetic) and a fifth category termed “cryptogenic (30%)” which includes all strokes of unknown causes [4]. The correct identification of stroke etiology is important to start a specific secondary prevention treatment in order to effectively reduce the risk for recurrent strokes. Furthermore, multiple potential causes can be present simultaneously leading to uncertainty in identifying the relevant cause and difficulties in prioritizing treatment decisions. Biomarkers have the potential to be supportive in assigning the relevant stroke etiology.

Due to the varying causes of the different stroke subtypes (e.g., atherosclerosis versus cardiac embolism), it can be hypothesized that the various stroke etiologies may be associated with a specific expression pattern of serum proteins. To date, no biological marker exists that provides a precise etiology of stroke [5]. However, specific blood‐based biomarker measurements might have the potential to improve the classification of ischemic stroke mechanisms and thus increase the chance of a specific therapy. A better understanding of the pathophysiology of ischemic stroke would lead to improved preventive measures in addition to diagnostic and therapeutic improvement. Therefore, in the present study we aimed to evaluate potential associations between different etiologic stroke subtypes and a wide panel of blood‐based proteins in the ‘Stroke Cohort Augsburg’ (SCHANA).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study sample

This study is based on data from the SCHANA study, an observational single‐center stroke cohort study that included 945 patients aged 18 years and older treated at Augsburg University Hospital between September 2018 and November 2019 [6]. For the present cross‐sectional investigation, we excluded patients with a cerebral hemorrhage or unavailable fasting blood samples. Thus, 364 patients with ischemic stroke were included in the analysis. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München (Reference: 18–196). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians. This study followed the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) statements [7].

Data collection

Patients enrolled in the SCHANA study completed a standardized questionnaire after the acute stroke event during their hospitalization. The questionnaire collected demographic information, medical history, risk factors and lifestyle factors. Clinical data were gathered from the participants' medical records. Fasting status (yes, no) before blood collection and the elapsed time between hospital admission and blood collection were documented. Several clinical variables including modified Rankin Scale (mRS) [8], National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) [9] and stroke treatments (e.g., systemic thrombolysis, thrombectomy) were recorded. Stroke etiology as determined by the treating physicians according to the TOAST criteria was grouped into the following five categories: (1) large artery atherosclerosis, (2) cardioembolism, (3) small vessel disease, (4) other determined or (5) undetermined etiology, with the last two categories combined for the present analysis. Strokes of unexplained etiology (with no landmark diagnostic finding, in the presence of competing causes or with inadequate diagnostic testing) were referred to as cryptogenic strokes.

Assessment of blood parameters

From each SCHANA participant about 70 mL blood were collected during the hospital stay. The blood samples were processed immediately. Serum was kept at room temperature, centrifuged and separated after 30 min. They were aliquoted into sample tubes at the Chair of Epidemiology, University Hospital Augsburg, and frozen at −80°C until they were used for biomarker analyses.

Concentrations of 52 cytokines and chemokines were measured in serum using the Bio‐Plex Pro™ Human Cytokine Screening Panel, ICAM‐1 set and VCAM‐1 set, plus the Pro™ Human TH17 cytokine sCD40L set and IL31 set (all Bio‐Rad, USA) according to the manufacturer's specifications. Briefly, 50 μL of diluted magnetic beads were placed in the wells and washed two times. Then the standard samples (dilution 1:4 HCSP and IL31, sCD40L, 1:100 VCAM/ICAM), blank and controls were pipetted into the respective well and incubated between 30 and 60 min on the shaker at 850 ± rpm at room temperature depending on the panel (60 min IL31 and sCD40L, 30 min VCAM/ICAM and HCSP). This incubation was followed by a three‐fold wash step, the addition of the diluted detection antibody and an incubation of 30 min. After another wash step, streptavidin phycoerythrin (PE) was added and incubated for 10 min. Finally, the plate was washed three more times and re‐suspended with 125 microliter Bio‐Plex assay buffer. All incubation steps were performed at room temperature. Measurements were carried out on a Luminex xMAP technology instrument using Bioplex Manager Software.

Measurements were performed in six batches, and the technical variation between the plates was corrected using the intensity normalization defined as , where and represent the plate‐specific and overall medians, respectively. Values specified as below or above the lower or upper limit of detection, respectively, were replaced by the lowest or highest detectable level according to the manufacturer's specifications, if present in fewer than 25% of the cases. Otherwise the corresponding cytokine was excluded from the statistical analyses. Finally, cytokine‐specific outliers (exceeding μ ± 3σ) were excluded resulting in 39 cytokines, which were used for further analyses (Table S1).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described as median and interquartile range (IQR) and categorical variables as absolute and relative frequencies. Differences between the four stroke categories were tested using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test in the case of continuous variables and Fisher's exact test in the case of categorical variables.

Multivariable linear regression models were performed to assess the cross‐sectional associations between the ischemic stroke subtypes (exposure) and the 39 inflammation biomarkers (outcomes). Regarding the model performance and comparability of estimates, all inflammation parameters were log2‐transformed and ‐standardized (i.e., division of individual cytokines by their standard deviation), respectively. The confounder selection process based on directed acyclic graphs revealed the following variables to be controlled for in the regression models. Age (years), body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2), the time between admission and blood collection (days) and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) were considered as continuous variables to minimize residual confounding. Sex, smoking status (never, ex, current), hypertension (yes, no), incident stroke (yes, no) and any treatment (systemic thrombolysis or thrombectomy, no) were considered as categorical variables. Robustness of results was assessed by performing subgroup analyses excluding patients who underwent reperfusion therapies.

All regression assumptions were ensured in the following way. Linearity between all continuous variables and a specific outcome was tested and, if necessary, corrected using restricted cubic splines. More precisely, in each regression model, where linearity could not be assumed for at least one continuous variable based on the likelihood‐ratio test, the optimum number of variable‐specific knots (between three and five) was determined with regard to the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Normality of residual‐distribution was ensured by visual assessment of the model‐specific Q‐Q plots. Highly leveraged outliers leading to violation of the normally distributed residuals were removed from the analyses. Heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation were tested using the Breusch–Pagan test and Durbin–Watson test, respectively. Finally, the variance inflation factor was calculated to assess multicollinearity.

All statistical tests were performed based on the significance level =0.05. Regarding multiple testing issues, p‐values obtaining from the 39 regression models were false discovery rate (FDR)‐adjusted. All analyses were done using the statistical software R (version 4.2.2).

RESULTS

As presented in Table 1, the median age ranged significantly between 67 (IQR: 60; 78) years in the small vessel occlusion and 76 (IQR: 63.5; 81.25) in the cardioembolic stroke subtypes. Median duration between admission and blood collection varied between 3.87 days (IQR: 3.26; 5.31) for patients with a small vessel occlusion stroke and 5.28 days (IQR: 3.84; 6.82) for patients with large vessel atherosclerotic subtype. The NIHSS as indicator for stroke severity was lower in patients with cryptogenic stroke compared with the other subtypes. Sex, hypertension and receipt of any therapy also differed significantly between etiologies (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics regarding etiology of stroke according to the TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) classification.

| Characteristic | Etiology | P‐value a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 364) | Large artery atherosclerosis (n = 86) | Cardioembolic (n = 88) | Small vessel occlusion (n = 73) | Cryptogenic/other (n = 117) | ||

| Age | 364 | 70.5 (63; 80) | 76 (63.5; 81.25) | 67 (60; 78) | 68 (56; 78) | 0.027 |

| BMI | 358 | 26.45 (24.19; 29.30) | 26.7 (24.47; 29.76) | 27.27 (24.70; 31.01) | 25.87 (22.96; 29.38) | 0.238 |

| Time to blood collection (days) | 363 | 5.28 (3.84; 6.82) | 4.55 (2.94; 5.89) | 3.87 (3.26; 5.31) | 4.71 (3.30; 5.88) | 0.002 |

| NIHSS | 360 | 2 (0; 6) | 2 (1; 5.75) | 2 (0; 3) | 1 (0; 3) | 0.013 |

| Sex | 364 | 0.020 | ||||

| Males | 57 (0.663) | 53 (0.602) | 40 (0.548) | 53 (0.453) | ||

| Females | 29 (0.337) | 35 (0.398) | 33 (0.452) | 64 (0.547) | ||

| Smoking status | 364 | 0.246 | ||||

| Current smoker | 15 (0.174) | 16 (0.182) | 14 (0.192) | 18 (0.154) | ||

| Ex‐smoker | 42 (0.488) | 40 (0.455) | 27 (0.37) | 40 (0.342) | ||

| Never smoker | 29 (0.337) | 32 (0.364) | 32 (0.438) | 59 (0.504) | ||

| Re‐stroke event | 363 | 0.823 | ||||

| No | 65 (0.756) | 66 (0.75) | 51 (0.708) | 90 (0.769) | ||

| Yes | 21 (0.244) | 22 (0.25) | 21 (0.292) | 27 (0.231) | ||

| Revascularization | 364 | 0.028 | ||||

| No | 67 (0.779) | 57 (0.648) | 60 (0.822) | 94 (0.803) | ||

| Yes | 19 (0.221) | 31 (0.352) | 13 (0.178) | 23 (0.197) | ||

| Hypertension | 364 | 0.001 | ||||

| No | 9 (0.105) | 21 (0.239) | 8 (0.11) | 39 (0.333) | ||

| Yes | 77 (0.895) | 67 (0.761) | 65 (0.89) | 78 (0.667) | ||

Note: Continuous data presented as median (interquartile range) and tested with the Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test. Categorical data presented as absolute and relative frequencies.

Bold type denotes statistical significance.

Tested with the Fisher's exact test (categorical variables) or the Kruskal‐Wallis rank sum test (continuous variables).

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Notable cytokines included interleukin‐6 (IL‐6), interleukin‐16 (IL‐16) and macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), which had the lowest median levels in the microangiopathic subtype and the highest levels in large vessel atherosclerotic strokes (Table 2). The same applied reversely for the human interferon gamma‐induced protein (IP‐10). Further differences were observed for the human monokine induced by gamma interferon (MIG) and stromal cell‐derived‐factor 1 alpha (SDF‐1a) levels for patients with atherothrombotic stroke compared with the undetermined and cardioembolic strokes, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of inflammation markers regarding etiology of stroke according to the TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) classification.

| Characteristic | Etiology | P‐value a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 364) | Large artery atherosclerosis (n = 86) | Cardioembolic (n = 88) | Small vessel occlusion (n = 73) | Cryptogenic /other (n = 117) | ||

| CTACK | 364 | 16.431 (15.96; 16.922) | 16.578 (16.009; 17.01) | 16.293 (15.896; 16.72) | 16.343 (15.852; 16.983) | 0.279 |

| Eotaxin | 359 | 6.788 (6.152; 7.213) | 6.773 (6.387; 7.221) | 6.807 (6.457; 7.245) | 6.777 (6.24; 7.183) | 0.762 |

| FGF_basic | 364 | 24.675 (24.246; 25.319) | 24.63 (23.891; 25.242) | 24.675 (23.888; 25.07) | 24.675 (23.987; 25.075) | 0.536 |

| G_CSF | 363 | 13.927 (13.415; 14.552) | 13.927 (13.428; 14.45) | 13.864 (13.372; 14.419) | 13.79 (13.332; 14.373) | 0.708 |

| GM_CSF | 360 | 2.094 (1.717; 2.534) | 2.226 (1.339; 2.806) | 1.99 (1.406; 2.438) | 2.226 (1.726; 2.768) | 0.151 |

| GROA | 364 | 12.187 (11.732; 12.541) | 12.135 (11.697; 12.424) | 12.195 (11.577; 12.501) | 12.152 (11.627; 12.565) | 0.799 |

| HGF | 364 | 15.543 (15.041; 16.112) | 15.615 (14.994; 16.313) | 15.213 (14.917; 15.742) | 15.52 (14.968; 15.924) | 0.088 |

| ICAM_1 | 359 | 21.81 (21.56; 22.192) | 21.7 (21.294; 22.006) | 21.746 (21.481; 22.121) | 21.615 (21.243; 22.078) | 0.121 |

| IFN_g | 363 | 7.391 (7.126; 7.825) | 7.234 (6.749; 7.57) | 7.35 (6.997; 7.911) | 7.253 (6.918; 7.875) | 0.298 |

| IFNa | 364 | 8.612 (8.194; 8.931) | 8.56 (8.192; 8.908) | 8.493 (8.092; 8.896) | 8.56 (8.2; 8.875) | 0.803 |

| IL_13 | 364 | 1.68 (1.286; 2.078) | 1.68 (1.347; 2.064) | 1.68 (1.376; 2.14) | 1.68 (1.183; 2.099) | 0.796 |

| IL_16 | 354 | 7.437 (6.978; 7.943) | 7.373 (6.996; 8.038) | 7.172 (6.769; 7.615) | 7.411 (6.812; 7.879) | 0.041 |

| IL_18 | 364 | 9.13 (8.641; 9.902) | 9.275 (8.718; 9.802) | 9.392 (8.934; 10.033) | 9.138 (8.658; 9.719) | 0.277 |

| IL_1b | 363 | 4.876 (4.459; 5.262) | 4.876 (4.459; 5.259) | 4.876 (4.459; 5.309) | 4.876 (4.531; 5.537) | 0.797 |

| IL_1ra | 363 | 12.678 (12.213; 13.154) | 12.614 (12.303; 12.969) | 12.566 (12.112; 13.071) | 12.537 (12.157; 12.984) | 0.766 |

| IL_2ra | 364 | 13.695 (13.299; 14.178) | 13.592 (13.095; 14.073) | 13.452 (13.119; 13.786) | 13.504 (13.032; 13.886) | 0.093 |

| IL_4 | 364 | 4.794 (4.347; 5.16) | 4.723 (4.364; 5.232) | 4.72 (4.275; 5.223) | 4.794 (4.432; 5.192) | 0.887 |

| IL_6 | 359 | 1.824 (1.444; 2.189) | 1.636 (1.15; 2.271) | 1.38 (0.87; 1.635) | 1.444 (0.957; 1.819) | 0.001 |

| IL_7 | 361 | 6.376 (6.03; 6.873) | 6.376 (6.042; 6.782) | 6.376 (6.125; 6.778) | 6.376 (5.703; 6.786) | 0.623 |

| IL_8 | 361 | 4.327 (3.991; 4.96) | 4.375 (3.957; 4.8) | 4.179 (3.846; 4.657) | 4.171 (3.878; 4.57) | 0.08 |

| IL_9 | 364 | 18.86 (18.403; 19.184) | 18.814 (18.255; 19.258) | 19.064 (18.582; 19.373) | 18.883 (18.382; 19.431) | 0.319 |

| IP_10 | 359 | 9.126 (8.894; 9.683) | 9.34 (9.062; 9.86) | 9.424 (8.975; 9.995) | 9.223 (8.855; 9.568) | 0.045 |

| lif | 364 | 11.27 (10.898; 11.806) | 11.198 (10.781; 11.711) | 11.27 (10.932; 11.723) | 11.27 (10.895; 11.674) | 0.730 |

| MCP_1_MCAF | 361 | 7.22 (6.589; 7.746) | 7.23 (6.736; 7.818) | 7.324 (6.68; 8.142) | 7.372 (6.921; 7.906) | 0.446 |

| MCSF | 364 | 6.77 (6.378; 7.26) | 6.816 (5.999; 7.322) | 6.838 (6.402; 7.282) | 6.632 (6.152; 7.096) | 0.314 |

| MIF | 364 | 16.532 (15.976; 17.091) | 16.409 (15.832; 17.068) | 16.259 (15.604; 16.636) | 16.487 (15.849; 17.163) | 0.025 |

| MIG | 360 | 6.955 (6.491; 7.494) | 6.931 (6.523; 7.517) | 6.904 (6.55; 7.574) | 6.713 (6.186; 7.125) | 0.016 |

| MIP_1a | 364 | 2.751 (2.098; 3.375) | 2.411 (1.858; 3.072) | 2.528 (2.045; 3.007) | 2.478 (1.869; 3.11) | 0.308 |

| MIP_1b | 363 | 19.025 (18.493; 19.493) | 18.802 (18.384; 19.54) | 19.105 (18.52; 19.744) | 19.026 (18.47; 19.648) | 0.405 |

| PDGF_BB | 360 | 17.333 (16.982; 17.823) | 17.196 (16.739; 17.744) | 17.236 (16.878; 17.7) | 17.344 (16.955; 17.892) | 0.133 |

| RANTES | 363 | 20.09 (19.762; 20.378) | 20.26 (19.817; 20.5) | 20.203 (19.922; 20.478) | 20.261 (19.92; 20.73) | 0.15 |

| SCF | 364 | 14.674 (14.201; 15.171) | 14.715 (14.34; 15.272) | 14.466 (14.095; 14.928) | 14.578 (14.029; 15.099) | 0.12 |

| SCGFB | 364 | 36.211 (35.709; 36.68) | 36.258 (35.683; 36.626) | 36.226 (35.784; 36.774) | 36.264 (35.657; 36.763) | 0.98 |

| SDF‐1a | 363 | 18.643 (18.309; 18.951) | 18.931 (18.684; 19.318) | 18.66 (18.128; 18.927) | 18.795 (18.385; 19.175) | 0.001 |

| TNF_a | 362 | 19.184 (18.627; 19.731) | 19.336 (18.711; 19.821) | 19.138 (18.651; 19.578) | 19.104 (18.609; 19.626) | 0.499 |

| TNFb | 364 | 20.21 (19.794; 20.636) | 20.29 (19.68; 20.69) | 20.329 (19.979; 20.795) | 20.335 (19.771; 20.742) | 0.601 |

| TRAIL | 363 | 11.316 (10.617; 11.714) | 11.316 (10.615; 11.759) | 11.419 (10.948; 11.932) | 11.316 (10.723; 11.732) | 0.556 |

| VCAM_1 | 313 | 22.732 (22.394; 23.203) | 22.864 (22.495; 23.365) | 22.82 (22.521; 23.121) | 22.789 (22.361; 23.328) | 0.703 |

| VEGF | 340 | 5.307 (4.887; 5.615) | 5.374 (5.088; 5.663) | 5.288 (4.765; 5.487) | 5.352 (4.868; 5.733) | 0.333 |

Note: Data presented as median (interquartile range).

Bold type denotes statistical significance.

Tested with the Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test. Meanings of the cytokine abbreviations are listed in Table S1.

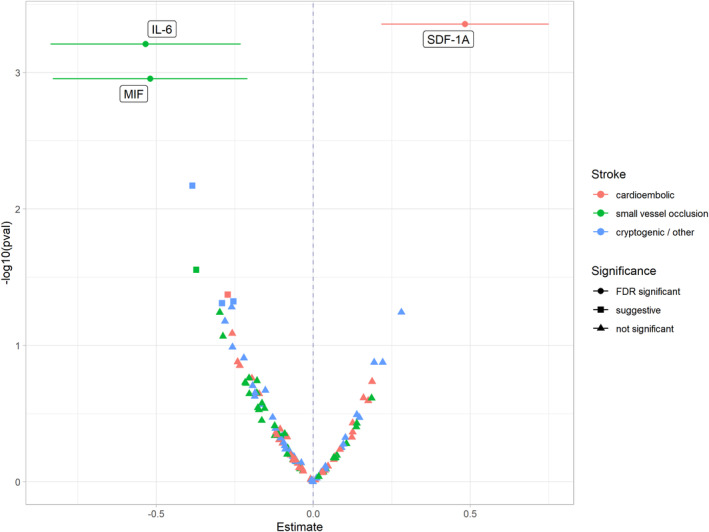

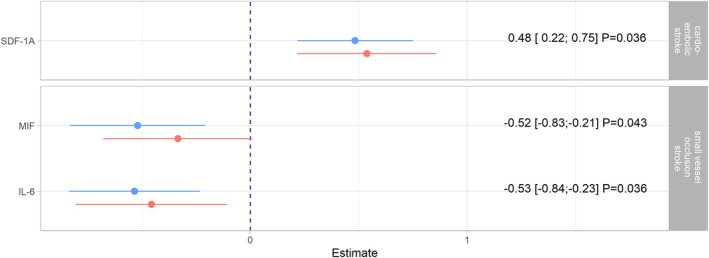

Point estimates presented in the following can be interpreted as the mean difference in ‐standardized cytokine levels on the log2‐scale between a specific etiology and large artery atherosclerosis subtype as the reference group. SDF‐1a levels were significantly higher in the cardioembolic stroke subjects compared with the large vessel atherosclerotic subtype (β = 0.48; 95% CI 0.22; 0.75; adjusted p‐value = 0.036) (Figures 1 and 2). Furthermore, both MIF (β = −0.52; 95% CI −0.83; −0.21; adjusted p‐value = 0.043) and IL‐6 (β = −0.53; 95% CI −0.84; −0.23; adjusted p‐value = 0.036) levels were significantly lower in the small vessel disease subtype. ICAM 1 levels in the cardioembolic subtype, IL‐16 levels in the microangiopathic subtype as well as ICAM 1, IL‐6 and IL‐7 levels in the undetermined subtype were significantly lower before but not after correction for multiple testing (designated as “suggestive significant” in the Figures). All cytokine‐specific associations can be found in Figures S1–S3. Subgroup analyses excluding all subjects who received reperfusion therapy yielded consistent estimates (Figure S4) and thus supported the findings of main analyses (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Volcano plot of results from multivariable linear regression models investigating the associations between etiology of stroke and inflammation markers. In the linear regression models, it was controlled for age (years), body mass index (kg/m2), the time between admission and blood collection (days), the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), sex, smoking status (never, ex, current), hypertension (yes, no), incident stroke (yes, no) and any treatment (systemic thrombolysis or thrombectomy, no). Atherothrombotic subtype is the reference category. Estimates and 95% confidence intervals represent the standard deviation change in cytokine levels on the log2‐scale. On the y‐axis the –log10‐transormed p‐values are given. The significance level of an association is labeled as suggestive if the association lost its significance after correction for multiple testing.

FIGURE 2.

Notable associations from the main analyses (Figure 1) presented in graphical and tabular form as point estimates, 95% confidence intervals and false‐discovery rate (FDR)‐adjusted p‐values. These estimates (colored blue) are compared with estimates from subgroup analyses (colored red), in which patients undergoing reperfusion therapies were excluded. In the linear regression models, it was controlled for age (years), body mass index (kg/m2), the time between admission and blood collection (days), the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), sex, smoking status (never, ex, current), hypertension (yes, no), incident stroke (yes, no) and – only in the main analyses – for any treatment (systemic thrombolysis or thrombectomy, no).

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study suggest that differences in serum proteins may be useful for distinguishing different ischemic stroke etiologies. We observed that the biomarker SDF‐1a was significantly positively associated with the cardioembolic stroke subtype when compared with large artery atherosclerosis strokes. Small vessel occlusion strokes were independently inversely related to the biomarkers MIF and IL‐6. However, there was no association between cryptogenic strokes and any biomarker after adjustment for multiple testing.

In recent years, research has intensified regarding the relationship between blood biomarkers and various stroke mechanisms [10, 11]. Some prior studies have been conducted to examine whether markers of systemic inflammation such as C‐reactive protein (CRP) and pro‐inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL‐6) can be used to differentiate between stroke subtypes [12, 13]. Other studies in this context focused on common lipid parameters (e.g., total cholesterol, triglycerides, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol) [14, 15, 16] or on hemostatic biomarkers (e.g., D‐dimer concentration) [17, 18]. Various biomarkers were found to be significantly associated with cardioembolic stroke, such as D‐dimer, CRP, IL‐6, BNP/NT‐proBNP, while common lipids and inflammation markers (CRP, NLR) were related to the atherosclerotic stroke subtype [19].

In our study, patients with cardioembolic stroke subtype had significantly higher levels of SDF‐1a, also known as CXCL12, a member of the CXC chemokine family. SDF‐1a is a chemoattractant cytokine with diverse biological functions including stem cell migration, proliferation, cell apoptosis and angiogenesis [20] and is constitutively expressed by many tissues, including the heart [21] and the brain [22]. It is known that SDF‐1a has various functions in the brain during development and in adulthood [23]. Furthermore, it is upregulated under pathological conditions such as ischemic stroke [24]. Studies have shown that cell death of cortical neurons after stroke is reduced by administration of SDF‐1a. This is probably due to a stimulation of angiogenesis and neurogenesis and due to a modulation of inflammatory responses [25]. SDF‐1a is upregulated in the penumbra of ischemic stroke and has a role in promoting repair [26]. In a Chinese acute stroke cohort, elevated serum levels of SDF‐1a were associated with increased lesion volumes and stroke severity [27] and predicted unfavorable outcome and mortality [28]. Cardioembolic strokes are associated with larger infarct sizes and poorer prognosis, thus higher serum SDF‐1a levels may not be due to other pathophysiological mechanisms but rather due to infarct size. Conversely, elevated circulating SDF‐1a levels seem to indicate an increased risk of future strokes [29, 30].

In our study we observed significantly lower concentrations of MIF and IL‐6 in patients with small vessel strokes in comparison with large artery atherosclerosis strokes. MIF is a proinflammatory cytokine with pleiotropic properties and involved, among others, in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases [31]. It is basically found in various cell types and tissues and is released as a response to acute stress or inflammation [32]. It is associated with the release of proinflammatory cytokines, overcomes the inhibitory effects of glucocorticoids, and exerts a chemokine function that causes increased migration and recruitment of leukocytes to inflamed tissues [31]. There is accumulating evidence that MIF is a multifaceted protein with various functions within the central nervous system. MIF plays a role in neurological diseases but its role appears diverse with both beneficial and adversary effects [32]. While some prior studies found a protective function of MIF in stroke [33], other studies suggested an association of MIF concentrations with increasing clinical severity of stroke and a poor early outcome [29]. A study in mice demonstrated that MIF promotes cell death and aggravates neurologic symptoms after experimental stroke [30]. Very recently, another study in mice concluded that MIF exerts a neuroprotective function after ischemic stroke by protecting neuronal cells from apoptosis while inducing the inflammatory process, facilitating neurogenesis [34].

A prior study showed that patients with small vessel occlusion stroke subtype had significantly lower serum levels of IL‐6, an important regulator of the immune system, compared with large artery atherosclerosis strokes [35]. These results were consistent with our findings, which revealed that the highest IL‐6 levels were found in patients with large artery atherosclerosis stroke compared with the other stroke subtypes, thus supporting the hypothesis that inflammation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of the large artery atherosclerosis stroke subtype. An inflammatory response including endothelial and coagulation mechanisms contributes pathophysiologically to neuronal injury in ischemic stroke. The lower IL‐6 concentrations in patients with small vessel subtype strokes may therefore be an expression of the lower acute neurological deficit in patients with this subtype, which typically occurs without any change detectable on computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain [35, 36].

Strengths and limitations

There are limitations to the present study. First, this was a cross‐sectional study, thus only associations rather than causal relationships could be shown. Second, blood samples were collected at different time points after the acute stroke event. Thus, time between admission and blood collection was considerable and there were statistically significant differences between the various stroke subtypes. This shortcoming may have influenced the results. We attempted to minimize potential bias by accounting for this fact in the regression models. Third, no neuroimaging parameters could be considered in the present analysis. Fourth, the reason why a stroke was classified as cryptogenic was not provided, and why patients with multiple etiologies were assigned to the cryptogenic stroke subtype and could not be excluded from the analyses. This fact could partially explain the high proportion of cryptogenic strokes in our study. In addition, ESUS cases were not explicitly defined in our dataset. Fifth, the study was carried out by using a single‐center approach. Fifth, mainly Caucasians were included in the present study, so the results do not apply to individuals of other ethnic origins.

Strengths of our study include the availability of a large panel of standardized measured protein biomarkers to investigate the research question. In addition, selection of confounding factors on a theoretical basis and optimization of each regression model with respect to its assumptions led to robust results and stronger evidence.

In conclusion, using a broad panel of inflammatory proteins in acute stroke patients we found some differences according to the stroke subtype. The immense progress in the measurement of proteomics offers the possibility to study and understand the pathophysiology of stroke subtypes in greater detail. Further studies are needed to validate and confirm identified biomarkers in diverse study populations before they can be used in the clinical setting to further improve stroke management and patient outcomes. In addition to the postulated etiology of stroke and classification into stroke subtypes, future biomarker studies should also consider infarct size in neuroimaging.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Jakob Linseisen, Markus Naumann, Michael Ertl. Methodology: Christine Meisinger, Dennis Freuer, Timo Schmitz. Formal analysis and investigation: Dennis Freuer, Timo Schmitz, Philipp Zickler. Writing – original draft preparation: Christine Meisinger, Dennis Freuer. Writing – review and editing: Timo Schmitz, Michael Ertl, Philipp Zickler, Markus Naumann, Jakob Linseisen. Funding acquisition: Michael Ertl. Resources: Jakob Linseisen, Markus Naumann.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The study was funded by the Medical Faculty, University of Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1 and Figure S1‐S4

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to all members of the Department of Neurology and Clinical Neurophysiology at the University Hospital Augsburg and the Chair of Epidemiology, University of Augsburg, for their support. Moreover, we express our appreciation to all study participants. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Meisinger C, Freuer D, Schmitz T, et al. Inflammation biomarkers in acute ischemic stroke according to different etiologies. Eur J Neurol. 2024;31:e16006. doi: 10.1111/ene.16006

Christa Meisinger and Dennis Freuer contributed equally to this work.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139(10):e56‐e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344‐e418. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke. 1993;24(1):35‐41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Caplan LR, Donnan GA, Hennerici MG. Classification of stroke subtypes. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27(5):493‐501. doi: 10.1159/000210432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Montaner J, Ramiro L, Simats A, et al. Multilevel omics for the discovery of biomarkers and therapeutic targets for stroke. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(5):247‐264. doi: 10.1038/s41582-020-0350-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ertl M, Meisinger C, Linseisen J, Baumeister SE, Zickler P, Naumann M. Long‐term outcomes in patients with stroke after in‐hospital treatment‐study protocol of the prospective stroke cohort Augsburg (SCHANA study). Medicina (Kaunas). 2020;56(6):280. doi: 10.3390/medicina56060280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Banks JL, Marotta. CA. Outcomes validity and reliability of the modified Rankin scale: implications for stroke clinical trials: a literature review and synthesis. Stroke. 2007;38(3):1091‐1096. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258355.23810.c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kasner SE, Chalela JA, Luciano JM, et al. Reliability and validity of estimating the NIH stroke scale score from medical records. Stroke. 1999;30(8):1534‐1537. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.8.1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sonderer J, Katan Kahles. M. Aetiological blood biomarkers of ischaemic stroke. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145:w14138. doi: 10.4414/smw.2015.14138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jickling GC, Sharp. FR. Biomarker panels in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2015;46(3):915‐920. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boos CJ, Anderson RA, Lip. GY. Is atrial fibrillation an inflammatory disorder? Eur Heart J. 2006;27(2):136‐149. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guo Y, Lip GY, Apostolakis. S. Inflammation in atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(22):2263‐2270. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Laloux P, Galanti L, Jamart. J. Lipids in ischemic stroke subtypes. Acta Neurol Belg. 2004;104(1):13‐19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yuan BB, Luo GG, Gao JX, et al. Variance of serum lipid levels in stroke subtypes. Clin Lab. 2015;61(10):1509‐1514. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2015.150118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zambrelli E, Emanuele E, Marcheselli S, Montagna L, Geroldi D, Micieli G. Apo(a) size in ischemic stroke: relation with subtype and severity on hospital admission. Neurology. 2005;64(8):1366‐1370. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158282.83369.1D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu LB, Li M, Zhuo WY, Zhang YS, Xu AD. The role of hs‐CRP, D‐dimer and fibrinogen in differentiating etiological subtypes of ischemic stroke. PloS One. 2015;10(2):e0118301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ageno W, Finazzi S, Steidl L, et al. Plasma measurement of D‐dimer levels for the early diagnosis of ischemic stroke subtypes. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(22):2589‐2593. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.22.2589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harpaz D, Seet RCS, Marks RS, Tok AIY. Blood‐based biomarkers are associated with different ischemic stroke mechanisms and enable rapid classification between cardioembolic and atherosclerosis etiologies. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10(10):804. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10100804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aiuti A, Webb IJ, Bleul C, Springer T, Gutierrez‐Ramos JC. The chemokine SDF‐1 is a chemoattractant for human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells and provides a new mechanism to explain the mobilization of CD34+ progenitors to peripheral blood. J Exp Med. 1997;185(1):111‐120. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.1.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wei YJ, Tang Y, Li J, et al. Cloning and expression pattern of dog SDF‐1 and the implications of altered expression of SDF‐1 in ischemic myocardium. Cytokine. 2007;40(1):52‐59. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hickey KN, Grassi SM, Caplan MR, Stabenfeldt SE. Stromal cell‐derived factor‐1a autocrine/paracrine signaling contributes to spatiotemporal gradients in the brain. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2021;14(1):75‐87. doi: 10.1007/s12195-020-00643-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zendedel A, Johann S, Mehrabi S, et al. Activation and regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome by intrathecal application of SDF‐1a in a spinal cord injury model. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(5):3063‐3075. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9203-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cui L, Qu H, Xiao T, Zhao M, Jolkkonen J, Zhao C. Stromal cell‐derived factor‐1 and its receptor CXCR4 in adult neurogenesis after cerebral ischemia. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2013;31(3):239‐251. doi: 10.3233/RNN-120271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shyu WC, Lin SZ, Yen PS, et al. Stromal cell‐derived factor‐1 alpha promotes neuroprotection, angiogenesis, and mobilization/homing of bone marrow‐derived cells in stroke rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324(2):834‐849. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen BY, Wang X, Chen LW, Luo ZJ. Molecular targeting regulation of proliferation and differentiation of the bone marrow‐derived mesenchymal stem cells or mesenchymal stromal cells. Curr Drug Targets. 2012;13(4):561‐571. doi: 10.2174/138945012799499749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu P, Xiang JW, Jin SX. Serum CXCL12 levels are associated with stroke severity and lesion volumes in stroke patients. Neurol Res. 2015;37(10):853‐858. doi: 10.1179/1743132815Y.0000000063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cheng X, Lian YJ, Ma YQ, Xie NC, Wu CJ. Elevated serum levels of CXC chemokine ligand‐12 are associated with unfavorable functional outcome and mortality at 6‐month follow‐up in Chinese patients with acute ischemic stroke. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54(2):895‐903. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9645-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schutt RC, Burdick MD, Strieter RM, Mehrad B, Keeley EC. Plasma CXCL12 levels as a predictor of future stroke. Stroke. 2012;43(12):3382‐3386. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.660878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gu XL, Liu L, Lu XD, Liu ZR. Serum CXCL12 levels as a novel predictor of future stroke recurrence in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53(5):2807‐2814. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9151-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thiele M, Donnelly SC, Mitchell RA. OxMIF: a druggable isoform of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in cancer and inflammatory diseases. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10(9):e005475. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2022-005475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leyton‐Jaimes MF, Kahn J, Israelson. A. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a multifaceted cytokine implicated in multiple neurological diseases. Exp Neurol. 2018;301(Pt B):83‐91. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zis O, Zhang S, Dorovini‐Zis K, Wang L, Song W. Hypoxia signaling regulates macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) expression in stroke. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;51(1):155‐167. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8727-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim JA, Kim YY, Lee SH, Jung C, Kim MH, Kim DY. Neuroprotective effect of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) in a mouse model of ischemic stroke. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(13):6975. doi: 10.3390/ijms23136975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tuttolomondo A, di Raimondo D, Pecoraro R, Arnao V, Pinto A, Licata G. Inflammation in ischemic stroke subtypes. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18(28):4289‐4310. doi: 10.2174/138161212802481200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Licata G, Tuttolomondo A, di Raimondo D, Corrao S, di Sciacca R, Pinto A. Immuno‐inflammatory activation in acute cardio‐embolic strokes in comparison with other subtypes of ischaemic stroke. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101(5):929‐937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 and Figure S1‐S4

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.