Traditionally, the management of newly presenting patients has two stages—assessment and then treatment. However, this two stage approach has limitations. When underlying disease pathology is diagnosed there may be delays in starting effective treatment. If no disease is found reassurance is often ineffective. In both cases many patients are left feeling uncertain and dissatisfied. Lack of immediate information and agreed plans may mean that patients and their families become anxious and draw inappropriate conclusions, and an opportunity to engage them fully in their management is missed.

Mismatch of expectations and experiences

| What patients want | What some patients get |

| To know the cause | No diagnosis |

| Explanation and information | Poor explanation that does not address their needs and concerns |

| Advice and treatment | Inadequate advice |

| Reassurance | Lack of reassurance |

| To be taken seriously by a sympathetic and competent doctor | Feeling that doctor is uninterested or believes symptoms are unimportant |

Disease centred versus patient centred consultations

Disease centred—Doctor concentrates on standard medical agenda of diagnosis through systematic inquiries about patient's symptoms and medical history

Patient centred—Doctor works to patient's agenda, including listening and allowing patient to explain all the reasons for attending, feelings, and expectations. Decision making may be shared, and plans are explicit and agreed. Patient centred consultations need take no longer than traditional disease centred consultations

If simple diagnosis is supplemented with fuller explanation, patient satisfaction and outcomes are improved. This can be achieved by integrating assessment and treatment. The aim of an integrated consultation is that the patient leaves with a clear understanding of the likely diagnosis, feeling that concerns have been addressed, and knowledge of the treatment and prognosis (that is, the assessment becomes part of the treatment). This approach can be adopted in primary and secondary care and can be applied to patients with or without an obvious disease explanation for their symptoms. The integrated approach may require more time, but this is offset by a likely reduction in patients' subsequent attendance and use of resources.

This article describes principles and practical procedures for effective communication and simple interventions. They can be applied to various clinical situations—such as straightforward single consultation, augmenting brief medical care, and promoting an effective start to continuing treatment and care.

General principles

Integrating physical and psychological care

Somatic symptoms are subjective and have two components, a somatic element (a bodily sensation due to physiology or pathology) and a psychological element (related to thoughts and beliefs about the symptoms). Traditional management focuses only on the somatic component, with the aim of detecting and treating underlying pathology. Addressing the psychological component in the consultation as well, with simple psychological interventions, is likely to reduce distress and disability and reduce the need for subsequent specialist treatment.

Providing continuity

Seeing the same doctor on each visit increases patient satisfaction. Continuity may also improve medical outcomes, including distress, compliance, preventive care, and resource use. Problems resulting from lack of continuity can be minimised by effective communication between doctors.

Communication between doctors

Reduce need for communication between doctors by providing continuity of care whenever possible

Brief, structured letters are more likely to be read than lengthy, unstructured letters

Letters from primary to secondary care should provide relevant background information and a clear reason for referral

Letters from secondary to primary care should provide only essential information, address the needs of referrer, and outline a proposed management plan and what has been discussed with patient

Avoid using letters for medical records purposes rather than communication

The telephone can be a prompt and effective means of communication and is particularly useful in complex cases

Involving the patient

The psychological factors of beliefs and attitudes about illness and treatment are major determinants of outcome. Hence, strategies that increase understanding, sense of control, and participation in treatment can have large benefits. One example is written management plans agreed between doctor and patient. This approach is the basis of the Department of Health's “Expert Patient Programme,” which aims to help patients to “act as experts in managing their own condition, with appropriate support from health and social care services.”

Gaining understanding of patients' concerns

Read referral letter or notes, or both, before seeing patient

Encourage patients to discuss their presenting concerns without interruption or premature closure

Explore patients' presenting complaints, concerns, and understanding (beliefs)

Inquire about disability

Inquire about self care activities

Show support and empathy

Use silence appropriately

Use non-verbal communication such as eye contact, nods, and leaning forward

Thinking “family”

Relatives' illness beliefs and attitudes are also crucial to outcome and are therefore worth addressing. Key people may be invited to join a consultation (with the patient's permission) and their concerns identified, acknowledged, and addressed. Actively involving relatives, who will spend more time with the patient than will the doctor, allows them to function as co-therapists.

Effective communication

Gaining and demonstrating understanding

Simple techniques can be used to improve communication. The first two stages of the three function approach (see previous article) are appropriate. The first stage is building a relationship in which a patient gives his or her history and feels understood. The second stage is for the doctor to share his or her understanding of the illness with the patient. In cases that are more complicated it may be most effective to add an additional brief session with a practice or clinic nurse.

Showing your understanding of patients' concerns

Relay key messages—such as, “The symptoms are real,” “We will look after you,” and “You're not alone”

Take patients seriously and make sure they know it

Don't dismiss presenting complaints, whether or not relevant pathology is found

Explain your understanding of the problem—what it is, what it isn't, treatment, and the future. A diagram may help

Consider offering a positive explanation in the absence of relevant physical pathology

Reassure

Avoid mixed messages

Encourage and answer questions

Share decisions

Communicate the management plan effectively, both verbally and in writing

Provide self care information, including advice on lifestyle change

Explain how to get routine or emergency follow up, and what to look out for that would change the management plan

Providing information for patients

Patients require information about the likely cause of their illness, details of any test results and their meaning, and a discussion of possible treatments. Even when this information has been given in a consultation, however, many patients do not understand or remember what they are told. Hence, the provision of simple written information can be a time efficient way of improving patient outcomes.

Providing information

Invite and answer questions

Use lay terms, and build on patient's understanding of illness wherever possible

Avoid medical jargon and terms with multiple meanings, such as “chronic”

Involve relatives

Provide written material when available

Provide a written management plan when appropriate

One way of providing written information is to copy correspondence such as referral and assessment letters to the patient concerned. For those not used to doing this, it may seem a challenge, but any changes needed to make the letters understandable (and acceptable) to patients are arguably desirable in any case. Letters should be clearly structured, medical jargon minimised, pejorative terms omitted, and common words that may be misinterpreted (such as “chronic”) explained.

Well written patient information materials (leaflets and books) are available, as are guidelines for their development. The National Electronic Library of Health (www.nelh.nhs.uk) is a new internet resource that aims to provide high quality information for healthcare consumers and is linked to NHS Direct Online (www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk/main.jhtml). There are also many books to recommend—such as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS/ME): The Facts (see Further reading list). Information is most helpful if it addresses not only the nature of the problem, its prognosis, and treatment options, but also self care and ways of coping.

The complexity of reassurance

General reassurance

To know it will be OK

To know I will be looked after

To know there are others like me

Reassurance about cause

To know what it is

To know what it is not

To know it's not serious“There are several possible causes, not just cancer”“It's not cancer”“It will get better”

Reassurance about cure

To know it can be treated

To know it will be treated

To know how it will be treated

To know the complaint will go away

The assessment as treatment

Reassurance

Worry about health (health anxiety) is a common cause of distress and disability in those with and without serious disease. Reassurance is therefore a key component of starting treatment.

The first step is to elicit and acknowledge patients' expectations, concerns, and illness beliefs. This is followed by history taking, examination, and if necessary investigation. Premature reassurance (such as “I'm sure its nothing much”) may be construed as the doctor not taking the problem seriously. Finally, the explanation should address all of a patient's concerns and is best based on the patient's understanding of how his or her body functions, which may differ from the doctor's.

Characteristics of brief psychological intervention

Brief, single session intervention

Suitable for more complex problems, such as in secondary care

Delivered with or soon after clinic attendance

Integrated with usual care

Uses cognitive understanding of health anxiety

Minimises negative aspects of patient experience

Reinforces positive aspects of patient experience

Provides explicit explanation and reassurance

A modest increase in consultation time, provision of written information, and perhaps the use of trained nursing staff to facilitate information giving, can all enhance doctor-patient communication and, therefore, reassurance. Although extra time and effort may be needed, it may well reduce subsequent demand on resources.

Being positive

Doctors themselves are potentially powerful therapeutic agents. There is evidence that being deliberately positive in a consultation may increase this effect. In one randomised trial, general practice patients received either a positive consultation (firm diagnosis and good prognosis) or a non-positive consultation (no firm diagnosis and uncertain prognosis). Two weeks later, the positive consultation, which was simple and brief, had improved symptoms, with a number needed to treat of four (95% confidence interval 3 to 9).

Using tests as treatment

Tests should ideally be informative and reassuring for both doctors and patients. However, there is increasing evidence that tests may not reassure some patients and may even increase their anxiety. This is most likely with patients who are already anxious about their health. When weighing the pros and cons of ordering a test, doctors should take account of the psychological impact on their patient (positive and negative).

Providing explanations after negative investigation

Evidence based summary

The quality of communication, both in history taking and in discussing a management plan, influences patient outcome

Patients should be encouraged to take an active role in maintaining or improving their own health, and doctors should ensure they are given the necessary information and opportunities for self management

Reassurance involves eliciting and acknowledging patients' expectations, concerns, and illness beliefs

Coulter A, Entwistle V, Gilbert D. Sharing decisions with patients: is the information good enough? BMJ 1999;318:318-22

Di Blasi Z, Harkness E, Ernst E, Georgiou A, Kleijnen J. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet 2001;357:575-762

Stewart M. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J 1995;152:1423-33

Thomas KB. General practice consultations: is there any point in being positive? BMJ 1997;294:1200-2

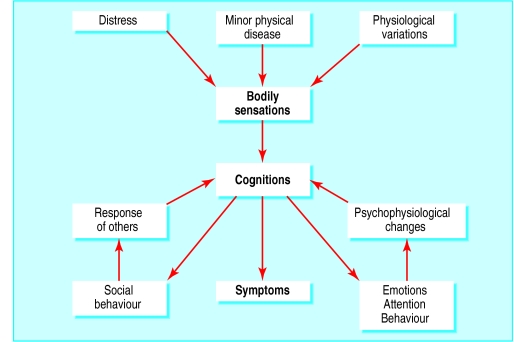

Even when tests are reported as normal, some patients are not reassured. Such patients may benefit from an explanation of what is wrong with them, not just what is not wrong. A cognitive behavioural model can be used to explain how interactions between physiology, thoughts, and emotion can cause symptoms without pathology. Simple headache provides an analogy: the pain is real, and often distressing and disabling, but is usually associated with “stress.” Diagnoses such as “tension headache” and “irritable bowel syndrome” can be helpful in reducing patients' anxiety about sinister causes for their symptoms.

Planning for the future

Maintaining and increasing activities

Sometimes patients unnecessarily avoid or reduce their activities for fear it will make their illness worse. This coping strategy magnifies disability. Planning a graded return towards normal activities is one of the most effective ways of helping such patients. A plan should specify clearly what activity, for how long, when, with whom, and how often. It is best if the plan is written down and reviewed regularly. A collaborative approach increases the chances of success.

Follow up

Positively following up patients who have presented for the first time can be an effective use of time. It allows review and modification of the management plan and may be particularly effective if the same doctor is seen.

Further reading

Balint M. The doctor, his patient, and the illness. Tunbridge Wells: Pitman Medical, 1957

Department of Health. The NHS plan—A plan for investment. A plan for reform. London: DoH, 2000

Campling F, Sharpe M. Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS/ME): the facts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000

Department of Health. The expert patient: a new approach to chronic disease management for the 21st century. 2001 (www.ohn.gov.uk/ohn/people/ep_report.pdf

Figure.

Taking time to listen to and address patients' ideas, concerns, and expectations can improve outcomes (A clinical lesson with Doctor Charcot at the Saltpêtrière by Pierre André Brouillet (1857-c1920))

Figure.

A simple cognitive model of physical symptoms. A cognitive model is one in which the patient's thoughts and beliefs are seen as central to the aetiology, perception, and presentation of the problem

Acknowledgments

The painting of Charcot is reproduced with permission of Bridgeman Art Library.

Footnotes

Jonathan Price is clinical tutor in psychiatry in the department of psychiatry, University of Oxford. Laurence Leaver is general practitioner at Jericho Health Centre, Oxford.

The ABC of psychological medicine is edited by Richard Mayou, professor of psychiatry, University of Oxford; Michael Sharpe, reader in psychological medicine, University of Edinburgh; and Alan Carson, consultant neuropsychiatrist, NHS Lothian, and honorary senior lecturer, University of Edinburgh. The series will be published as a book in winter 2002.