Abstract

BACKGROUND

The etiological diagnosis of intracranial hypertension is quite complicated but important in clinical practice. Some common causes are craniocerebral injury, intracranial space-occupying lesion, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and hydrocephalus. When a patient presents with intracranial hypertension, the common causes are to be considered first so that other causes would be dismissed. With the morbidity lower than 9%, neuromelanin is very rare. Common symptoms include nerve damage symptoms, epilepsy, psychiatric symptoms, and cognitive disorders.

CASE SUMMARY

We present a patient with melanoma which manifested with isolated intracranial hypertension without any other neurological signs. A 22-year-old male had repeated nausea and vomiting for 2 mo with Babinski sign (+) on both sides, nuchal rigidity, and subarachnoid hemorrhage. He had been diagnosed with melanoma and was given surgery and whole-brain radiation. Ultimately, the patient died 2 mo later.

CONCLUSION

Malignant melanoma should be taken into consideration in the differential diagnosis of intracranial hypertension.

Keywords: Intracranial hypertension, Diagnosis, Melanoma, Neuromelanin, Case report

Core Tip: This manuscript is a case report. We report on a patient with malignant melanoma who primarily presented with intracranial hypertension. With no other symptoms except intracranial hypertension, the process of etiological diagnosis was hard and thought-provoking. Moreover, there are few melanoma cases that manifested with intracranial hypertension alone.

INTRODUCTION

With the morbidity lower than 9%[1], neuromelanin is rarely seen in the nervous system. Most of these are secondary and the metastatic sites of predilection are the ventricular system. From a report, the incidence of brain metastases of malignant melanoma is 8%-46% while 2 out of 3 patients are found to have brain metastasis according to autopsy results[2]. The Pia mater is often affected, and when widely affected, it is called meningeal melanomatosis. Common symptoms of meningeal melanomatosis include intracranial hypertension (IH), signs of meningeal irritation, and cranial nerve lesions[3]. However, its low morbidity, as well as the various and atypical symptoms lead to difficulty in diagnosis, a high rate of misdiagnosis and a poor prognosis[4]. 10% to 40% of melanomas may develop brain metastases in the course of the disease, with autopsy studies reporting a higher incidence (12%-73%). Approximately 6% to 11% of brain metastases originate from melanoma[5-7].

This case was primarily presented with IH without any other neurological symptoms. Physical examination was notable for the Babinski sign (+) on both sides and nuchal rigidity. There was a hairy nevus on the left side of the cheek and a pigment spot on the inside left lower arm. Head magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the meninges were widely thickening and enhanced. In the right cerebellopontine angle area, there were small nodular abnormal signals. After the investigation, the patient was finally diagnosed with secondary meningeal melanomatosis. Having informed this patient and his family members, this case and the related images were agreed to be reported, and the article was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ethical Research under Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 22-year-old man presented with repeated nausea and vomiting for 2 mo.

History of present illness

The head computed tomography (CT) scan done in another hospital showed subarachnoid hemorrhage while digital subtraction angiography (DSA) showed cerebral venous thrombosis.

History of past illness

His medical history was unremarkable.

Personal and family history

There was no other relevant personal or family history.

Physical examination

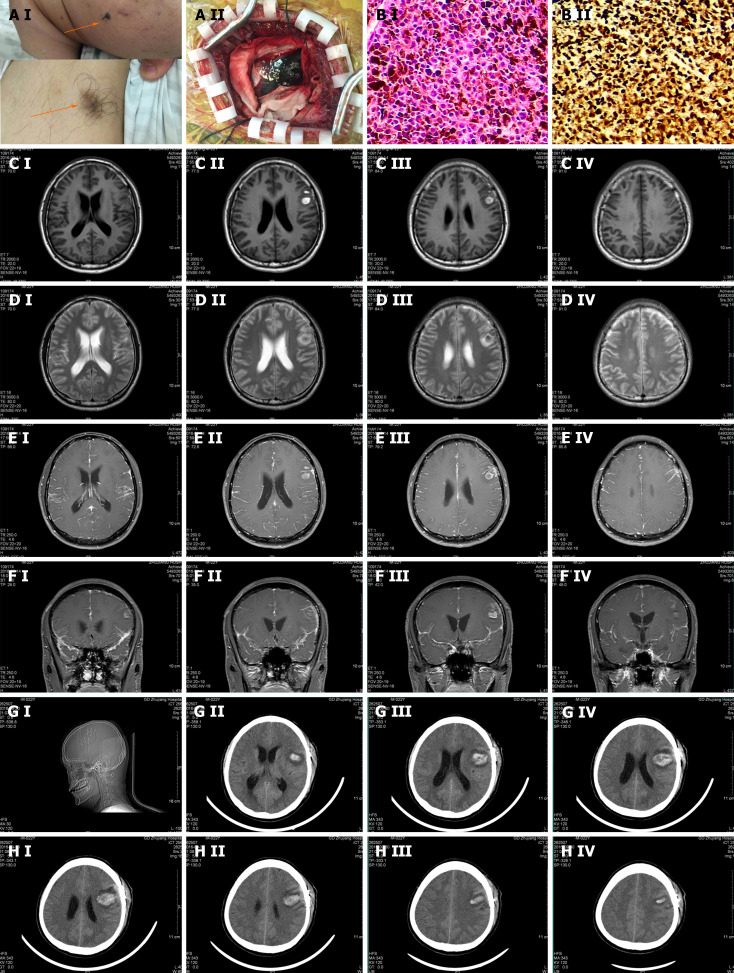

His physical examination was notable for the Babinski sign (+) on both sides and nuchal rigidity. On the left cheek, there was a hairy nevus with the size of 1.5 cm × 2.2 cm and the color was relatively dark with the edges blurred. It was as hard as a nasal tip and no ulcer was found. Meanwhile, there was a hairy pigment spot on the inside left lower arm with the size of 3.1 cm × 2.5 cm and the color was relatively light with the edges blurred, and the rigidity was the same as the former (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Pathological and imaging features of our melanoma patient. A: A-I: On the left cheek, there was a hairy nevus with the size of 1.5 cm × 2.2 cm. The color was relatively dark, and the edge blurred. It was as hard as a nasal tip and there was no ulcer around. Meanwhile, there was a hairy pigment spot on the inside left lower arm with the size of 3.1 cm × 2.5 cm. Its color was relatively light and the edge blurred. The rigidity was the same as the former. A-II: Histopathological examination: (Left frontal lobe lesion) the tumor tissue appears nest-like, with tumor cells showing polygonal shape, abundant cytoplasm, significant melanin content, large and deeply stained nuclei with irregular features. Immunohistochemistry: VIM (+), HMB45 (+), s-100 (+), Melin-A (+), P53 (+), CK (-), 70% Ki-67 (+). Pathological diagnosis: (Malignant melanoma) of the left frontal lobe. B: B-I: The distribution of carcinoma cells showed as nests (200 ×). The tumor cells were polygonal. The cell plasma was rich with a large amount of melanin in it. The nucleus was large and irregular. B-II: The tumor cells in immunohistochemical staining showed: VIM (+), HMB45 (+), S-100 (+), Melin-A (+), P53 (+), CK (-), KI-67 70% (+). CEDF: MRI showed a patch of long T1 and T2 signals on the left frontal lobe with nodular short T1 and T2 signals inside, and it was not enhanced in the enhancement scanning. However, in the enhancement scanning, the meninges were widely thickening and enhanced, especially around the abnormal signal lesion on the left frontal lobe and the tentorium of the cerebellum. There was a poor contrast agent filling in the superior sagittal sinus; C-I, II, III, and IV: T1 scan of the focal area; D-I, II, III, and IV: T2 scan of the focal area; E-I, II, III, and IV: Enhancement scan of the focal area; F-I, II, III, and IV: Enhancement scan on the focal area in coronal position; G and H: The head computed tomography (CT) scan after showed that there was still a high-density shadow on the left frontal lobe and the range got larger, inside new high-density shadow with the range of 23 mm × 45 mm was detected and the CT attenuation value was 58HU, and there was an edema zone around. In the adjacent sulci, there was a line-like high-density shadow. The ventricular system was enlarged.

Laboratory examinations

On September 18, 2016, we performed the lumbar puncture. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure was over 300 mmH2O. It appeared as yellow. The routine test showed that there was no fungal spores or hypha, no bacteria, and no Cryptococcus neoformans. GXMAg (-). Biochemistry indicators were as follows: Cl 101.2 mmol/L (120-130 mmol/L), glucose 5.0 mmol/L (2.8-4.5 mmol/L), ADA 10.3I U/L (0-8 mmol/L), and protein 1423 mg/L (150-450 mmol/L). TB-DNA was lower than the detection limit. Acid Fast Stain did not find the acid-fast bacillus. Meanwhile, we sent the CSF to the laboratory in Nanfang Hospital and found the tuberculostearic acid test was negative. Therefore, intracranial tuberculosis and fungi infection were excluded. On September 20, 2016, the cytological examination showed that there were a large number of atypical cells with pigment in them. Mitoses were widely observed. It was considered a malignant melanoma (Figure 1B).

Imaging examinations

On September 14, 2016, an MRI of the head was conducted and resulted as follows: (1) Left frontal lobe hematoma, mild communicating hydrocephalus, and signal abnormalities in the white matter beside the anterior horn of lateral ventricles; (2) The meninges were widely thickening and enhanced while there was poor contrast agent filling in the superior sagittal sinus; (3) In the right cerebellopontine angle area, there were small nodular abnormal signals; and (4) Signal abnormality in the basal ganglia on both sides was considered as lacunae vasorum. We suspected intracranial tuberculosis and fungi infection, while tumors cannot be excluded (Figure 1C-F). As for the operation findings, we presented them in Figure 1A. The pathological biopsy was performed and diagnosed as malignant melanoma. The head CT scan afterward showed that there was still a high-density shadow on the left frontal lobe and the range got larger, inside new high-density shadow with the range of 23 mm × 45 mm was detected and the CT attenuation value was 58 HU, and there was an edema zone around. In the adjacent sulci, there was a line-like high-density shadow. The ventricular system was enlarged (Figure 1G and H).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Malignant melanoma.

TREATMENT

The patient was sent to the neurosurgery department for surgical treatment. After the operation, the patient underwent whole-brain radiation.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient was kept in a coma and died 2 mo later. Follow-up was not applicable.

DISCUSSION

The patient could be diagnosed with malignant melanoma according to the cytological examination. Intracranial melanoma can be primary or secondary. Willis came up with 3 basic conditions to diagnose primary intracranial melanoma: (1) No melanoma was found on skin or eyeballs; (2) the patient has never gone through melanoma resection; and (3) no metastatic melanoma in internal organs[8]. Physical examination found that there was a hairy nevus on the left side of the cheek and a pigment spot on the inside left lower arm. Head MRI showed the meninges were largely thickening and enhanced. It thus should be secondary meningeal melanomatosis.

This case presented with IH. During clinical practice, the mechanism of IH is quite complicated: it can be caused by a narrow cranial cavity, enlargement of brain tissue, increase in CSF or cerebral blood flow, or an intracranial space-occupying lesion[9,10]. Various diseases can lead to IH, among which craniocerebral injury, intracranial space-occupying lesion, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and hydrocephalus are the most common.

Increased intracranial pressure can be classified into the following mechanisms: (1) Cerebral edema; (2) Space-occupying lesions; (3) Increased intracranial blood volume; (4) Increased CSF; and (5) Restricted intracranial space. The causes of elevated intracranial pressure in melanoma may include the first four mechanisms. The mechanism that leads to the IH of this patient might be as follows. Melanoma is rich in blood vessels, and they can spontaneously rupture. Meanwhile, the tumor cells have a predilection to the small blood vessels on the brain surface[11]. Therefore, hematoma and subarachnoid hemorrhage can easily occur. Subarachnoid hemorrhage and tumor cells are transferred to the subarachnoid space with CSF, which leads to the disturbance of CSF circulation and mild hydrocephalus. Both the enlargement of the brain parenchymal and the disorder of CSF circulation cause IH.

According to melanoma cases known for now that were primarily presented with neurological symptoms, the meningeal melanomatosis is often presented with nerve damage symptoms, epilepsy, psychiatric symptoms, and cognitive disorder[2]. The clinical significance of this patient is that he was simply presented with IH, which also makes it difficult to decide the reason for it. Chronic IH with an unremarkable medical history, intracranial space-occupying lesion, congenital malformation, bacterial meningitis, and intracranial tuberculosis and fungi infection thus should be first taken into consideration. Head CT and MRI are the first choices for patients with IH. The left frontal lobe hematoma and subarachnoid hemorrhage shown from the CT scan led us to think about cerebrovascular disease. However, the normal result in DSA excluded this suspect. The head MRI showed several nodules which could be a sign of intracranial tuberculosis and fungi infection. However, the negative result of the bacteriological examination excluded our guess. Because of the wide thickening and enhanced meninges with the abnormal signal nodules, we cannot dismiss intracranial tumors. At last, we verified that it was melanoma.

Melanoma brain metastases typically occur in areas with the highest blood flow, starting from the frontal lobe, while the involvement of the cerebellum, brainstem, and spinal cord is less common. Less than half of the lesions present as isolated tumors, causing corresponding neurological symptoms. Lesions smaller than 1 cm often remain asymptomatic, nonspecific complaints or neurological behavioral changes may occur. Melanoma metastases are more prone to hemorrhage (33%-50%) and seizures (25%), with the latter being the initial symptom in about 15% of cases. Diagnosing cutaneous melanoma can be highly challenging in certain patients, including those with psychiatric disorders, as these symptoms often serve as the first indicators of metastatic cancer[12]. Our patient, however, does not exhibit the early signs and symptoms mentioned earlier, such as altered mental status. It is worth noting that approximately 43% of patients with melanoma brain metastases may exhibit increased intracranial pressure, but it is typically accompanied by other neurological symptoms[13]. In addition, leptomeningeal enhancement diagnosed in the MRI, was the worst prognostic factor[14]. It may also explain the poor prognosis of our secondary melanomatosis patient.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, it is significant to consider and exclude cerebrovascular disease, intracranial infection, and tumors for the etiological diagnosis in patients with chronic IH. Meanwhile, because some tumors have no imaging manifestation, they must be emphasized enough in clinical practice.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: An informed consent form was signed by the parents of the case patient to approve the use of patient information or material for scientific purposes.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Clinical neurology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade C

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Dauyey K, Kazakhstan S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Cai YX

Contributor Information

Hai-Ting Xie, Department of Neurology, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510282, Guangdong Province, China.

Ding-Hao An, Department of Neurology, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Nanjing 210008, Jiangsu Province, China.

Duo-Bin Wu, Department of Neurology, Zhujiang Hospital of Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510282, Guangdong Province, China. 936861404@qq.com.

References

- 1.Tabouret E, Chinot O, Metellus P, Tallet A, Viens P, Gonçalves A. Recent trends in epidemiology of brain metastases: an overview. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4655–4662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sloan AE, Nock CJ, Einstein DB. Diagnosis and treatment of melanoma brain metastasis: a literature review. Cancer Control. 2009;16:248–255. doi: 10.1177/107327480901600307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pirini MG, Mascalchi M, Salvi F, Tassinari CA, Zanella L, Bacchini P, Bertoni F, D'Errico A, Corti B, Grigioni WF. Primary diffuse meningeal melanomatosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:115–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicolaides P, Newton RW, Kelsey A. Primary malignant melanoma of meninges: atypical presentation of subacute meningitis. Pediatr Neurol. 1995;12:172–174. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(94)00155-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amer MH, Al-Sarraf M, Baker LH, Vaitkevicius VK. Malignant melanoma and central nervous system metastases: incidence, diagnosis, treatment and survival. Cancer. 1978;42:660–668. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197808)42:2<660::aid-cncr2820420237>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel JK, Didolkar MS, Pickren JW, Moore RH. Metastatic pattern of malignant melanoma. A study of 216 autopsy cases. Am J Surg. 1978;135:807–810. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sampson JH, Carter JH Jr, Friedman AH, Seigler HF. Demographics, prognosis, and therapy in 702 patients with brain metastases from malignant melanoma. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:11–20. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.1.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma J, Zhang Z, Li S, Chen X, Wang S. Intracranial amelanotic melanoma: a case report with literature review. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:182. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0600-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman DI, Jacobson DM. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2002;59:1492–1495. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000029570.69134.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saitoh S, Momoi MY, Gunji Y. Pseudotumor cerebri manifesting as a symptom of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Pediatr Int. 2000;42:97–99. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-200x.2000.01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clifford JR, Kirgis HD, Connolly ES. Metastatic melanoma of the brain presenting as subarachnoid hemorrhage. South Med J. 1975;68:206–208. doi: 10.1097/00007611-197502000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avino A, Ion DE, Gheoca-Mutu DE, Abu-Baker A, Țigăran AE, Peligrad T, Hariga CS, Balcangiu-Stroescu AE, Jecan CR, Tudor A, Răducu L. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Particularities of Symptomatic Melanoma Brain Metastases from Case Report to Literature Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024;14 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14070688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byun J, Park ES, Hong SH, Cho YH, Kim YH, Kim CJ, Kim JH, Lee S. Clinical outcomes of primary intracranial malignant melanoma and metastatic intracranial malignant melanoma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018;164:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arai N, Kagami H, Mine Y, Ishii T, Inaba M. Primary Solitary Intracranial Malignant Melanoma: A Systematic Review of Literature. World Neurosurg. 2018;117:386–393. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.06.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]