Abstract

BACKGROUND

Paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM) may involve the hepatic pedicle and peripancreatic lymph nodes, cause damage to the bile duct and manifest, exceptionally, in combination with extrahepatic cholestasis (EHC), making investigation and treatment challenging.

AIM

To investigate the management of patients with visceral PCM admitted with EHC.

METHODS

All patients diagnosed with PCM treated in a public, tertiary teaching hospital between 1982 and 2020 were retrospectively evaluated. Those also identified with EHC were allocated to two groups according to the treatment approach for the purpose of comparing clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings, resources used for etiological diagnosis, treatment results, and prognosis. Statistical analyses were performed using the linear mixed-effects model (random and fixed effects), which was adjusted using the PROC MIXED procedure of the SAS® 9.0 software, and Fisher’s exact test.

RESULTS

Of 1645 patients diagnosed with PCM, 40 (2.4%) had EHC. Of these, 20 (50.0%) lived in the rural area and 29 (72.5%) were men, with a mean age of 27.1 years (3-65 years). Jaundice as first symptom and weight loss of at least 10 kg were observed in 16 patients (40.0%), and a mass in the head of the pancreas was observed in 8 (20.0%). The etiological diagnosis was made by tissue collection during surgery in 4 cases (10.0%) and by endoscopic methods in 3 cases (7.5%). Twenty-seven patients (67.5%) received drug treatment alone (Group 1), whereas 13 (32.5%) underwent endoscopic and/or surgical procedures in combination with drug treatment (Group 2). EHC was significantly reduced in both groups (40.7% in Group 1, with a mean time of 3 months; and 38.4% in Group 2, with a mean time of 7.5 months), with no statistically significant difference between them. EHC recurrence rates, associated mainly with treatment nonadherence, were similar in both groups: 37% in Group 1 and 15.4% in Group 2. The mortality rate was 18.5% in Group 1 and 23% in Group 2, with survival estimates of 71.3% and 72.5%, respectively, with no statistically significant difference.

CONCLUSION

Although PCM-related EHC is rare, it needs to be included in the differential diagnosis of malignancies, as timely treatment can prevent hepatic and extrahepatic sequelae.

Keywords: Cholestasis, Jaundice, Obstructive, Blastomycosis, Paracoccidioides, Diagnosis, Treatment

Core Tip: Paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM) associated with extrahepatic cholestasis (EHC) is a rare condition that can mimic malignant tumors. Correct diagnosis and treatment are essential to prevent unnecessary operations. Immunoelectrophoresis has proven to be a sensitive and reliable method for diagnosis and has influenced treatment decisions. We compared the results of two groups based on the treatment and/or diagnostic approach. Of 1645 patients diagnosed with PCM, 40 (2.4%) had EHC. This study is a unique contribution to the medical literature, with the largest sample size ever reported, by drawing attention to the diagnosis of PCM in patients with EHC, especially in endemic regions.

INTRODUCTION

Paracoccidioidomycosis (PCM) is a systemic fungal infection caused by inhalation or ingestion of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. The fungus enters the damaged respiratory, oral, or anal mucosa, predominantly affecting healthy adult men from rural areas. The location and type of injury vary with age. In older patients, there is a predominance of mucocutaneous and pulmonary lesions[1,2], whereas young people typically suffer from disseminated infection, with lymph node enlargement involving the digestive system and the abdominal lymphatic system[3,4].

The acute form of the disease affects the abdominal organs, and lesions often develop in the intestines and intra-abdominal lymph nodes[5]. Rarely, patients under 30 years of age present with severe infection characterized by diffuse reticuloendothelial system involvement[6], which may mimic systemic lymphoproliferative disorders[7]. Extrahepatic cholestasis (EHC) occurs in 2.2% to 6.6% of patients with PCM[8,9] and is often related to bile duct obstruction by lymph nodes in the hepatic pedicle and close to the head of the pancreas, wall injury, or, more rarely, hepatitis secondary to PCM[4,8].

In PCM-related EHC, the clinical presentation and biochemical and imaging findings may simulate epithelial and lymphatic neoplasms that affect the biliary and pancreatic ducts, making the process of differential diagnosis challenging[10,11]. In some cases, when the epidemiological and clinical aspects of PCM are not properly considered, the patient undergoes invasive tests, and the diagnosis is made by laparotomy and lymph node biopsy[11-13].

This study aims to highlight aspects of the approach and prognosis of PCM-related EHC, with the goal of guiding physicians and health care systems regarding the differential diagnosis of patients with EHC and wasting syndrome in endemic regions, as well as the adoption of strategies to ensure access and adherence to timely treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

The medical records of patients diagnosed with PCM treated from 1982 to 2020 at Hospital das Clínicas of Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto at University of São Paulo (HCFMRP-USP) were evaluated. HCFMRP-USP is a public, tertiary teaching hospital of reference in the Brazilian Unified Health System. Included patients were diagnosed with PCM based on serological tests and isolation of the fungus from lymph nodes, mucous membranes, skin, expansile lesions in the abdomen, and secretions from fistulized lymph nodes. EHC was confirmed by biochemical and imaging tests.

Diagnosis and treatment of PCM

For the purpose of comparing the approach, results, and prognosis, patients were allocated to two groups according to whether they received drug treatment alone or drug treatment in combination with endoscopic/surgical procedures for the diagnosis and treatment of EHC.

Group 1 (G1): Patients receiving drug treatment, which consisted of intravenous administration of amphotericin B, combined with oral sulfonamide or imidazole compounds, for a prolonged period if on an inpatient basis or for maintenance if on an outpatient basis.

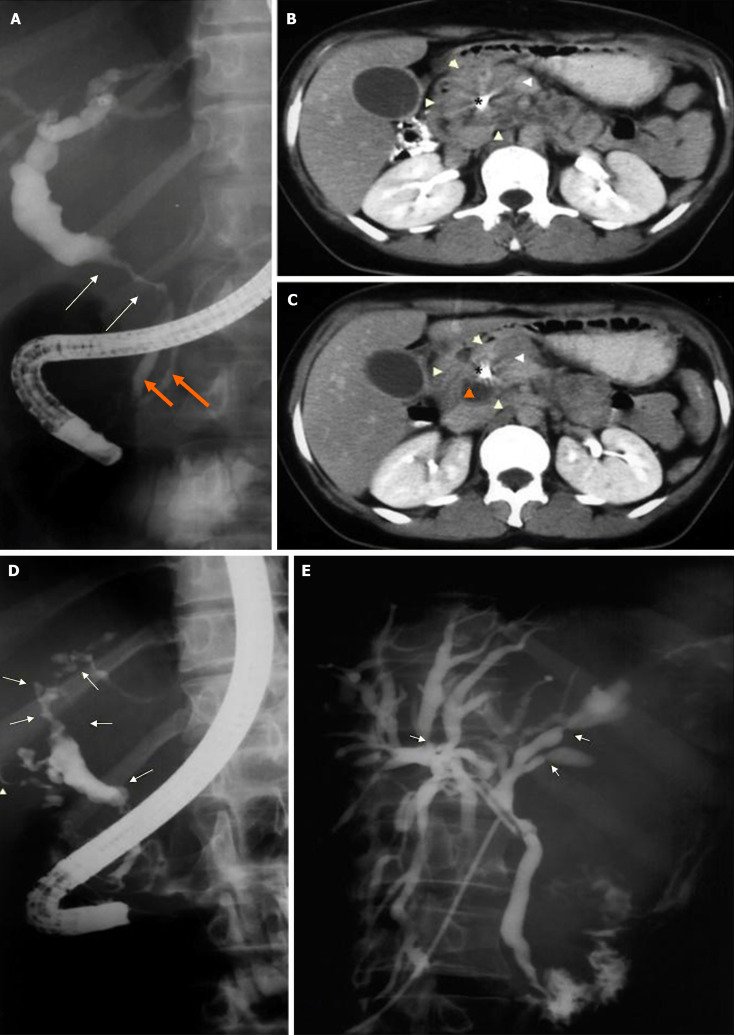

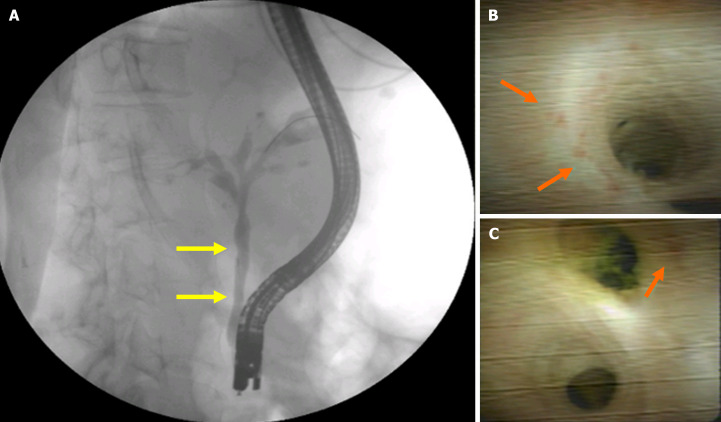

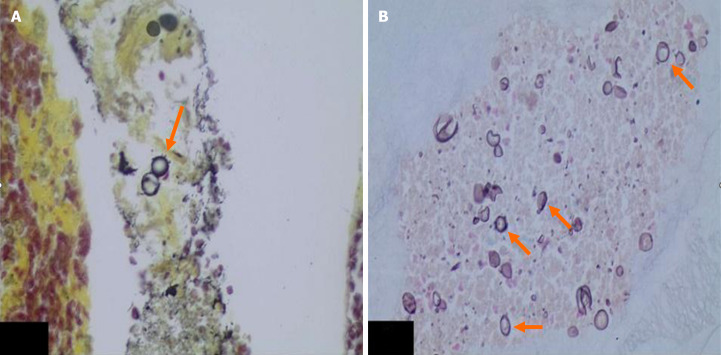

Group 2 (G2): Patients undergoing surgical and/or endoscopic procedures for the diagnosis and treatment of EHC. The procedures included cholecystectomy with radiological investigation of the bile ducts, biopsy of hilar or peripancreatic lymph nodes, biliodigestive anastomosis, and endoscopic procedures such as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with placement of a stent in the bile duct for drainage (Figure 1), endoscopic ultrasound (US)-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) for the diagnosis of abdominal masses, and biliary cholangioscopy for biopsy of the common bile duct wall (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

Paracoccidioidomycosis-related extrahepatic cholestasis mimicking cholangiocarcinoma and primary sclerosing cholangitis. A: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography showing abrupt stenosis of the common bile duct and irregular walls (white arrows). The intrahepatic bile duct is dilated, while the distal common bile duct and pancreatic duct have normal calibers (orange arrows); B and C: Computed tomography after placement of a plastic stent in the bile duct (asterisk*) showing enlargement of the pancreas head (white arrowheads) and a cystic component (orange arrow); D: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography before treatment showing irregularities in the wall of the intra and extrahepatic bile ducts, with areas of segmental stenosis and dilation (white arrows), similar to primary sclerosing cholangitis; E: T-tube cholangiography 1 month after drug treatment showing improvement of wall irregularities and areas of stenosis. There is slight residual dilation and restricted areas of stenosis (white arrows).

Figure 2.

Cholestasis, consumptive syndrome, and jaundice associated with blastomycosis. A: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography revealing irregularities in the wall of the common distal bile duct (yellow arrows); B and C: Images obtained by cholangioscopy biopsy of the distal common bile duct wall, which shows some superficial irregularity (orange arrows).

Figure 3.

Cholangioscopy biopsy. A and B: Presence of rounded fungal structures, detected by the Gomori’s methenamine silver (GMS) staining method, with multiple sporulation (orange arrows) compatible with paracoccidioidomycosis (GMS, 400 ×).

Statistical analysis and ethics approval

The number of patients with PCM identified during the study period determined the sample size. Statistical analyses were preformed using the linear mixed-effects model (random and fixed effects), which was adjusted using the PROC MIXED procedure of the SAS® 9.0 software. Fisher’s exact test was used to evaluate the variables found in the imaging tests and EHC recurrence between groups.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of HCFMRP-USP under number 4580249 on March 09, 2021.

RESULTS

Patients and symptoms

Among 1645 patients diagnosed with PCM during the study period, 40 (2.4%) had EHC. Of these, 20 (50.0%) lived in the rural area and 29 (72.5%) were men, with a mean age of 27.1 years (3 to 65 years).

Jaundice was the first symptom in 16 patients (40.0%). In the remaining patients, the mean time until EHC development was 34.3 months (1 month to 6.1 years). Daily fever was observed in 60.0% of patients, and weight loss of at least 10 kg was observed in 40%. Lymph node enlargement was observed in 85.0% of cases, hepatomegaly in 70.0%, and splenomegaly in 62.5%. Pruritus was the only symptom more commonly found in G2 (P = 0.03) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical manifestations of patients with paracoccidioidomycosis and extrahepatic cholestasis allocated to the clinical management (group 1) and clinical/endoscopic/surgical management (group 2) groups, n (%)

|

Symptom

|

Group 1 (n = 27)

|

Group 2 (n = 13)

|

P value

|

| Abdominal pain | 26 (96.2) | 10 (76.9) | 0.092 |

| Lymphadenomegaly | 25 (92.5) | 9 (69.2) | 0.074 |

| Hepatomegaly | 21 (77.7) | 7 (53.8) | 0.153 |

| Skin lesions | 21 (77.7) | 12 (92.3) | 0.393 |

| Choluria | 18 (66.6) | 7 (53.8) | 0.498 |

| Splenomegaly | 18 (66.6) | 7 (53.8) | 0.498 |

| Fever | 17 (62.9) | 7 (53.8) | 0.733 |

| Vomiting | 12 (44.4) | 5 (38.5) | 1.000 |

| Weight loss (> 10 kg) | 8 (29.6) | 8 (61.5) | 0.085 |

| Ascites | 7 (25.9) | 3 (23.0) | 1.000 |

| Pruritus | 6 (22.2) | 8 (61.5) | 0.031 |

Twenty-seven patients received drug treatment alone (67.5%; G1), while 13 (32.5%) underwent endoscopic treatment and/or surgery in addition to drug treatment (G2).

Laboratory tests and counterimmunoelectrophoresis

Total and direct bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and alanine aminotransferase levels were elevated in both groups, with no statistically significant difference between them. After treatment, there was a significant reduction in EHC markers, but also without statistically significant difference between the two groups. Hypoalbuminemia was observed in both groups. After treatment, a more pronounced improvement was observed in G1, but without statistically significant differences in the pre- and post-treatment comparison (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean level of total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, aspartate aminotransferase, and albumin before and after treatment of patients with paracoccidioidomycosis and extrahepatic cholestasis allocated to groups 1 and 2

|

Laboratory

|

Pre-group 1

|

Post-group 1

|

Pre-group 2

|

Post-group 2

|

| TB (mg/dL) | 5.10 | 1.90a | 6.60 | 0.90a |

| DB (mg/dL) | 3.20 | 0.40a | 4.40 | 0.28a |

| AP (U/L) | 1144.40 | 255.40a | 1045.00 | 192.70a |

| AST (U/L) | 94.10 | 55.90a | 99.60 | 45.60a |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 2.80 | 4.10 | 3.10 | 3.50 |

P > 0.05.

TB: Total bilirubin; DB: Direct bilirubin; AP: Alkaline phosphatase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase.

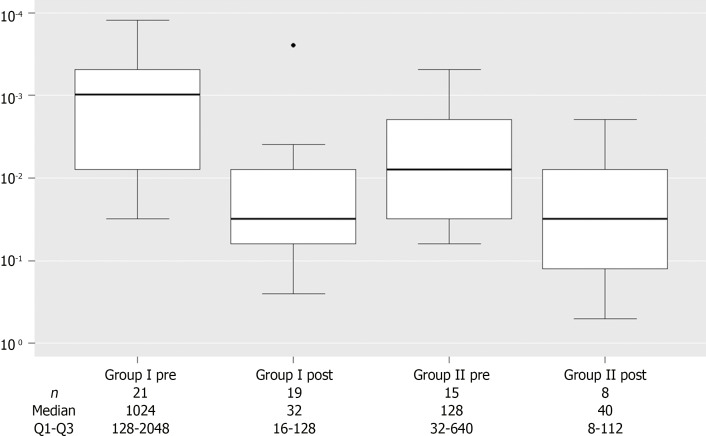

Counterimmunoelectrophoresis (CIE) was performed in all patients for the diagnosis of PCM and/or to evaluate treatment effect. Before treatment, CIE values were significantly elevated in G1. After treatment, there was a significant reduction in CIE in both groups, with no statistically significant difference between them (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Pre- and post-treatment counterimmunoelectrophoresis values in patients with paracoccidioidomycosis and extrahepatic cholestasis allocated to groups 1 and 2.

Imaging findings

US and computed tomography (CT) revealed dilation of the bile ducts, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and hilar or retroperitoneal lymph node enlargement (Table 3). Nine patients (32%) underwent ERCP: 1 procedure failed, 1 revealed normal bile ducts, and 7 revealed diffuse involvement of the bile duct wall, dilation of the bile ducts, and alternating segments of biliary narrowing and dilation. These changes may resemble those seen in primary sclerosing cholangitis (Figure 1D and E).

Table 3.

Incidence of abnormal imaging findings in patients with paracoccidioidomycosis and extrahepatic cholestasis allocated to groups 1 and 2, n (%)

|

Imaging finding

|

Group 1

|

Group 2

|

P value

|

|

n = 27

|

n = 13

|

||

| Abdominal lymphadenomegaly | 21 (77.7) | 10 (76.9) | 1.000 |

| Hepatomegaly | 20 (74.0) | 7 (53.8) | 0.283 |

| Biliary dilatation | 18 (66.6) | 10 (76.9) | 0.715 |

| Splenomegaly | 4 (14.8) | 6 (46.1) | 0.052 |

| Pancreatic head mass | 3 (11.0) | 5 (38.0) | 1.000 |

G1: Follow-up and evolution

Clinical treatment, consisting of intravenous amphotericin B or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole combined with oral sulfonamide or imidazole compounds for a prolonged period, was the initial option in 27 patients (67.6%) diagnosed with PCM. EHC resolution occurred in 13 patients (48.1%), with a mean time of 3 months. Two patients (7.4%) required second-line drug treatment: The first due to a significant increase in canalicular enzymes after receiving trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and the second due to therapeutic failure of the initial drug. Five patients (18.5%) experienced partial EHC improvement but were lost to follow-up before achieving complete resolution. Two patients (7.4%) experienced recurrence after the completion of clinical treatment: One patient was subsequently diagnosed with phagocytic immunodeficiency and hypogammaglobulinemia and was referred to the immunology department, and the other patient was lost to follow-up during the second therapeutic regimen.

There were 5 deaths in this group (18.5%), 2 children, and 3 adults. Four occurred in the first decade of follow-up and 1 in the second decade. One child had malnutrition and ascites and the other had multiple hepatic granulomas on autopsy. One of the adults was already in poor general condition, another died due to complications of chronic pancreatitis, and the medical records of the third adult were incomplete.

G2: Follow-up and evolution

Diagnosis and/or treatment was performed using an endoscopic/surgical approach in 13 patients (32.0%). ERCP was indicated in 9 patients (69.0%), 4 of whom (44.4%) underwent biliary drainage with a plastic stent. Surgical treatment was performed in 8 patients and, in addition to lymph node and/or liver biopsies, 2 patients underwent cholecystectomy and 3 underwent cholecystectomy plus biliodigestive anastomosis (hepaticojejunostomy in 2 and hepaticogastrostomy in 1).

The final diagnosis of PCM-related EHC was obtained by histopathological evaluation of lymph nodes, removed during surgery, in 4 patients (31.0%). In 2 patients, the diagnosis was made by EUS-FNA, while in 1 patient, it was made by ERCP followed by cholangioscopy and biopsy (Figures 2 and 3).

EHC resolution occurred in 7 patients (53.8%), with a mean time of 7.5 months. EHC did resolve after endoscopic biliary drainage in 2 patients (15.4%): One was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma during hospitalization, and the other continued to exhibit signs of EHC at lost to follow-up. The remaining patient (7.7%) showed signs of cholestasis 9 years after hepaticojejunostomy, but there was no record of EHC etiology.

Three patients died in this group (23.0%), all during the first decade of follow-up. These included 3 adults: 1 following ventriculoperitoneal shunting to treat PCM-related meningitis and 2 resulting from postoperative cardiorespiratory complications (one after open cholecystectomy, and the other after hepaticogastrostomy).

Recurrence and treatment adherence

Recurrence of EHC was observed in both groups, with no statistically significant difference between them. The main cause was nonadherence to treatment: 10 patients (37.0%) in G1 vs 2 patients (15.4%) in G2; P = 0.271).

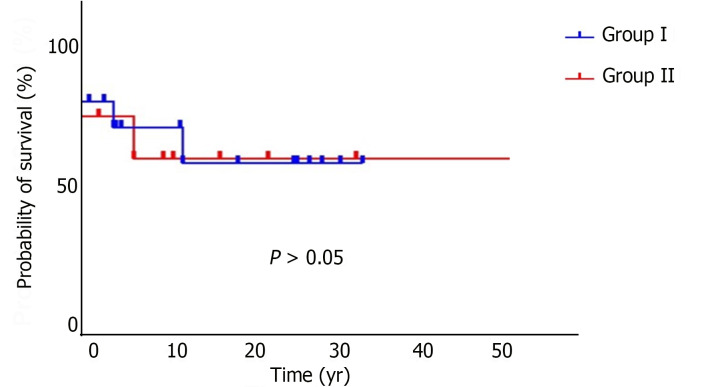

Survival estimates

During the follow-up period, 8 patients with PCM and EHC died, generating an overall mortality rate of 20.0%, with an estimated survival rate of approximately 71.2% in 38 years. The mortality rate was 18.5% in G1 and 23% in G2, with survival estimates of 71.3% and 72.5%, respectively, with no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) between the groups (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Survival estimates by group.

In G1, two children: One with malnutrition and ascites, and the other with several hepatic granulomas observed on autopsy; and an adult already admitted in poor general condition: Died within 12 d of admission. Another patient died from complications of chronic pancreatitis, and one patient lacked accurate information in the medical records.

In G2, 1 patient died after ventriculoperitoneal shunting to treat meningitis caused by PCM and 2 died from postoperative cardiorespiratory complications (1 from hepaticogastrostomy, and the other from open cholecystectomy).

Therefore, in G1, 4 patients died during the first decade of follow-up and 1 patient died during the second decade. In G2, 3 patients died during the first decade of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Among community-acquired systemic mycoses, PCM is the most relevant in South America[1,2,6]. The first case presenting with an abdominal tumor mimicking a malignant neoplasm was described in 1903[14]. Since then, sporadic reports have been published, highlighting the importance of including PCM in the differential diagnosis of abdominal masses in young men from rural areas and endemic regions[5,14].

On the other hand, there are few reports of biliary and peripancreatic involvement in PCM and the circumstances that lead some patients with EHC and consumptive syndrome to being initially treated based on a diagnosis of epithelial or lymphoid neoplasm[12,13,15]. Thus, the unprecedented characterization of a series of cases through critical analysis of the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches is justified, with emphasis on the incorporation of minimally invasive methods, such as puncture with EUS-guided biopsy of the lymph nodes and cholangioscopy with biopsy, as well as the adoption of measures that ensure adherence to treatment.

The number of patients with PCM who also presented EHC in this study was low (approximately 2.4%), but within the rates already reported in the scarce literature on the topic[13,16]. Young men (< 30 years of age) from rural areas, exposed to the environment, were the most affected. In young adults, the disease usually presents in the acute or subacute form and rapidly progresses, with lymphatic and hematogenous involvement associated with depressed cellular immunity and maintenance of the humoral immune response[7,8].

In patients with PCM-related EHC, the jaundice was the first sign in 40% of cases; in the remaining patients, it developed after a mean of 34.3 months (1.0 m to 6.1 y). The association between EHC and consumptive syndrome, which also occurs in 40% of cases, may simulate proliferative diseases, as most patients are young, or periampullary or bile duct neoplasms, as approximately 20% of patients have a mass in the head of the pancreas and 70% have stenosis with biliary duct dilation. This clinical presentation, associated with abnormal laboratory and imaging tests, should guide the investigation and performance of adequate tests.

In the first phase, patients in G2 who had EHC, pruritus more frequently than G1 patients, and consumptive syndrome without typical lesions in other organs underwent conventional surgery. However, with the advent of EUS and cholangioscopy in the last 20 years, an etiological diagnosis can be obtained, and biliary drainage can be performed using endoscopy combined with drug treatment. A minimally invasive approach can potentially reduce mortality, since 3 of the 4 deaths in G2 resulted from complications of conventional surgical procedures.

No statistically significant differences were observed in terms of disease severity, initial symptoms, or serum levels of alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyltransferase, bilirubin, aminotransferases, and albumin between the two groups. Radiological findings compatible with EHC also did not differ between the groups. CIE values were higher in G1 (P < 0.05), which may explain the diagnosis and treatment outcomes in this group. Therefore, with the exception of patients with suspected malignant pancreatic and biliary lesions and intense pruritus, among the parameters analyzed, no other clinical and laboratory factor supported the performance of endoscopic or surgical procedures.

EHC resolution was similar between the two groups, and jaundice did not resolve in only 2 patients (7.4%) after drug treatment. The mortality rate was 18.5% in G1 and 23% in G2, the latter being clearly associated with postoperative complications despite the severity of patients’ conditions. After excluding patients who did not adhere to treatment, there was no statistically significant difference in EHC recurrence between the two groups. After treatment, there was a trend toward normalization of serum levels of alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyltransferase, bilirubin, aminotransferases, and albumin and CIE values, with no statistically significant difference between the groups.

Among the 13 patients who underwent surgical treatment, 4 (30.8%) were suspected of having a malignant neoplasm of the head of the pancreas or the extrahepatic bile duct. The presence of marked EHC, without pain, accompanied by weight loss and intense pruritus is suggestive of epithelial neoplasm of the pancreatobiliary tract, in the same way that peripheral and abdominal lymph node involvement, associated with hepatosplenomegaly, is suggestive of lymphoproliferative disorders. In these patients, with relevant epidemiological data, it is extremely important to perform CIE and investigate the presence of fungi in the affected structures.

EHC was successfully resolved with clinical treatment in most patients. In those who used medications regularly, jaundice regressed in approximately 3 months, which is not enough time for EHC to cause irreversible hepatic damage. Therefore, the treatment of PCM-related EHC should always be drug-based, given its acceptable results and the number of complications arising from surgical therapy.

This study has some limitations, including its retrospective nature, extended study period (38 years), single-center design, and the fact that diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for patients with PCM-related EHC in the 1980s and 1990s were different from those used today. However, these limitations do not affect the conclusions, since this disease is rare, with an incidence of 2.4%. Furthermore, there is no case series in the literature describing a larger number of patients.

The results of this study allow us to infer that PCM-related EHC is rare, that it may occur in the acute or subacute form (juvenile type), and that it may present as disseminated/severe infection in some cases. It affects young men from rural areas, who present with weight loss, fever, and superficial and abdominal adenomegaly occurring in association with or preceding jaundice.

Drug treatment with oral or intravenous antifungals is effective, and adherence to clinical treatment promotes rapid clinical and laboratory recovery from EHC in most patients before irreversible liver damage occurs. Surgical treatment is reserved for patients for whom clinical treatment is ineffective, which is exceptional, or when PCM is suspected based on epidemiology and cannot be confirmed using conventional methods.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, young patients with EHC from rural areas, especially males, who present with painless jaundice and weight loss and in whom physical and imaging examinations reveal obstructive changes in the pancreatobiliary tract should be specifically evaluated for PCM, initially with laboratory tests and, if necessary, with the use of minimally invasive methods to diagnose and, eventually, drain the bile duct. Additionally, methods for monitoring PCM-related EHC, especially over 15 years, can reduce mortality.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of HCFMRP-USP (Approval No. 4580249).

Informed consent statement: The informed consent was waived from the patients as the study is retrospective, poses no risk to the patient’s health, and does not involve intervention or contact with them. Patient data will be anonymously compiled in a table with a password to minimize the risk of identity exposure.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

STROBE statement: The authors have read the STROBE Statement—checklist of items, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the STROBE Statement—checklist of items.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade A

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade A

P-Reviewer: Kotlyarov S, Russia S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

Contributor Information

José Sebastião dos Santos, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRP-USP), Departamento de Cirurgia e Anatomia, Ribeirão Preto 14049-900, São Paulo, Brazil.

Vitor de Moura Arrais, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRP-USP), Departamento de Cirurgia e Anatomia, Ribeirão Preto 14049-900, São Paulo, Brazil.

William José Rosseto Ferreira, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRP-USP), Departamento de Cirurgia e Anatomia, Ribeirão Preto 14049-900, São Paulo, Brazil.

Ricardo Ribeiro Correa Filho, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRP-USP), Departamento de Cirurgia e Anatomia, Ribeirão Preto 14049-900, São Paulo, Brazil.

Mariângela Ottoboni Brunaldi, Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRP-USP), Departamento de Patologia, Ribeirão Preto 14048900, São Paulo, Brazil.

Rafael Kemp, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRP-USP), Departamento de Cirurgia e Anatomia, Ribeirão Preto 14049-900, São Paulo, Brazil.

Ajith Kumar Sankanrakutty, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRP-USP), Departamento de Cirurgia e Anatomia, Ribeirão Preto 14049-900, São Paulo, Brazil.

Jorge Elias Junior, Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRP-USP), Departamento de Imagens Médicas, Hematologia e Oncologia Clínica, Ribeirão Preto 14048900, São Paulo, Brazil.

Fernando Bellissimo-Rodrigues, Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRP-USP), Departamento de Medicina Social , Ribeirão Preto 14015-010, São Paulo, Brazil.

Roberto Martinez, Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRP-USP), Departamento de Clínica Médica, Ribeirão Preto 14015-010, São Paulo, Brazil.

Edson Zangiacomi Martinez, Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRP-USP), Departamento de Medicina Social , Ribeirão Preto 14015-010, São Paulo, Brazil.

José Celso Ardengh, Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo (FMRP-USP), Departamento de Cirurgia e Anatomia, Ribeirão Preto 14049-900, São Paulo, Brazil and Hospital Moriah, Serviço de Endoscopia Digestiva, São Paulo 04084-002, São Paulo, Brazil. jcelso@uol.com.br.

Data sharing statement

Data can be acquired from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Peçanha PM, Peçanha-Pietrobom PM, Grão-Velloso TR, Rosa Júnior M, Falqueto A, Gonçalves SS. Paracoccidioidomycosis: What We Know and What Is New in Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. J Fungi (Basel) 2022;8 doi: 10.3390/jof8101098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hahn RC, Hagen F, Mendes RP, Burger E, Nery AF, Siqueira NP, Guevara A, Rodrigues AM, de Camargo ZP. Paracoccidioidomycosis: Current Status and Future Trends. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2022;35:e0023321. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00233-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silva AR, Vargas PA, Ribeiro AC, Martinez-Mata G, Coletta RD, Lopes MA. Fine needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of cervical tuberculosis and paracoccidioidomycosis. Cytopathology. 2010;21:66–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2303.2009.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maymó Argañaraz M, Luque AG, Tosello ME, Perez J. Paracoccidioidomycosis and larynx carcinoma. Mycoses. 2003;46:229–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2003.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prado FL, Prado R, Gontijo CC, Freitas RM, Pereira MC, Paula IB, Pedroso ER. Lymphoabdominal paracoccidioidomycosis simulating primary neoplasia of the biliary tract. Mycopathologia. 2005;160:25–28. doi: 10.1007/s11046-005-2670-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benard G, Neves CP, Gryschek RC, Duarte AJ. Severe juvenile type paracoccidioidomycosis in an adult. J Med Vet Mycol. 1995;33:67–71. doi: 10.1080/02681219580000141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Franco M, Montenegro MR, Mendes RP, Marques SA, Dillon NL, Mota NG. Paracoccidioidomycosis: a recently proposed classification of its clinical forms. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1987;20:129–132. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86821987000200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernardes Filho F, Sgarbi I, Flávia da Silva Domingos S, Sampaio RCR, Queiroz RM, Fonseca SNS, Hay RJ, Towersey L. Acute paracoccidioidomycosis with duodenal and cutaneous involvement and obstructive jaundice. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2018;20:21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cazzo E, Ferrer JA, Chaim EA. Obstructive jaundice secondary to paracoccidioidomycosis. Trop Gastroenterol. 2015;36:46–47. doi: 10.7869/tg.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teixeira F, Gayotto LC, De Brito T. Morphological patterns of the liver in South American blastomycosis. Histopathology. 1978;2:231–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1978.tb01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lima TB, Domingues MA, Caramori CA, Silva GF, de Oliveira CV, Yamashiro Fda S, Franzoni Lde C, Sassaki LY, Romeiro FG. Pancreatic paracoccidioidomycosis simulating malignant neoplasia: case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5750–5753. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i34.5750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaib E, de Oliveira CM, Prado PS, Santana LL, Toloi Júnior N, de Mello JB. Obstructive jaundice caused by blastomycosis of the lymph nodes around the common bile duct. Arq Gastroenterol. 1988;25:198–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shikanai-Yasuda MA, Conceição YM, Kono A, Rivitti E, Campos AF, Campos SV. Neoplasia and paracoccidioidomycosis. Mycopathologia. 2008;165:303–312. doi: 10.1007/s11046-007-9047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanchard R, Schwartz E, Binot J. Sur une blastomycose intra-peritonéale. Arch Parasitol. 1903;7:489. [Google Scholar]

- 15.da Cruz ER, Forno AD, Pacheco SA, Bigarella LG, Ballotin VR, Salgado K, Freisbelen D, Michelin L, Soldera J. Intestinal Paracoccidioidomycosis: Case report and systematic review. Braz J Infect Dis. 2021;25:101605. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2021.101605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiorillo M, Martinez R, Moraes C. Blastomicose sul americana. In: Del Negro G, Lacaz CS, Fiorillo M. Paracoccidioidomycose. São Paulo: Sarvier, 1982: 179-193. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be acquired from the corresponding author.