Early identification and active management of patients with renal impairment in primary care can improve outcomes

The number of patients with end stage renal disease is growing worldwide. About 20-30 patients have some degree of renal dysfunction for each patient who needs renal replacement treatment.1 Diabetes and hypertension are the two most common causes of end stage renal disease and are associated with a high risk of death from cardiovascular disease.

Mortality in patients with end stage renal disease remains 10-20 times higher than that in the general population. The focus in recent years has thus shifted to optimising the care of these patients during the phase of chronic kidney disease, before the onset of end stage renal disease. This review summarises current knowledge about the various stages of chronic renal disease, the risk factors that lead to progression of disease, and their association with common cardiovascular risk factors. It also provides strategies for intervention at an early stage of the disease process, which can readily be implemented in primary care, to improve the overall morbidity and mortality associated with chronic renal disease.

Summary points

Significant renal dysfunction might be present even when serum creatinine is normal or only slightly abnormal

Renal function declines progressively once creatinine clearance falls by about 25% of normal, but symptoms are often not apparent until renal failure is advanced

The baseline rate of urinary protein excretion is the best single predictor of disease progression

The prevalence of common cardiovascular risk factors is high in chronic renal disease; early identification and effective control of these risk factors is important to improve outcomes

Cardiovascular disease accounts for 40% of all deaths in chronic renal disease

Potentially reversible causes should be sought when renal function suddenly declines

Irreversible but modifiable complications (anaemia, cardiovascular disease, metabolic bone disease, malnutrition) begin early in the course of renal failure

Sources and search criteria

I searched Medline to identify recent articles (1992- 2001) related to the management of chronic renal disease and its complications. Key words used included chronic kidney disease, chronic renal failure, kidney disease, end stage renal disease, anaemia, erythropoietin, ischaemic heart disease, cardiac disease, lipid disorders, hyperparathyroidism, calcium, phosphate, nutrition, diabetes, and hypertension in relation to kidney disease. I also referred to the recent clinical practice guidelines published by the National Kidney Foundation.2

Diagnosis

Chronic renal failure is defined as either kidney damage or glomerular filtration rate less than 60 ml/min for three months or more.2 This is invariably a progressive process that results in end stage renal disease.

Serum creatinine is commonly used to estimate creatinine clearance but is a poor predictor of glomerular filtration rate, as it may be influenced in unpredictable ways by assay techniques, endogenous and exogenous substances, renal tubular handling of creatinine, and other factors (age, sex, body weight, muscle mass, diet, drugs).3 Glomerular filtration rate is the “gold standard” for determining kidney function, but its measurement remains cumbersome. For practical purposes, calculated creatinine clearance is used as a correlate of glomerular filtration rate and is commonly estimated by using the Cockcroft-Gault formula or the recently described modification of diet in renal disease equation (box B1).w1 w2

Box 1.

Methods for estimating creatinine clearance (glomerular filtration rate) in ml/min/1.73 m2

Stages of chronic renal disease

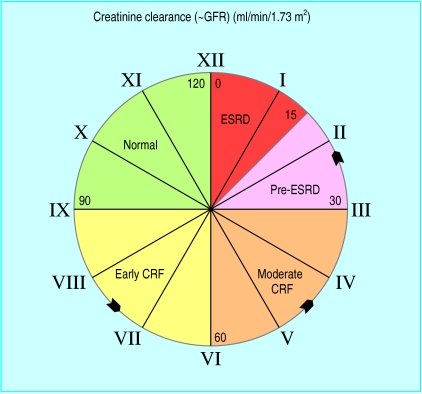

Chronic renal disease is divided into five stages on the basis of renal function (table, fig 1). Pathogenesis of progression is complex and is beyond the scope of this review. However, renal disease often progresses by “common pathway” mechanisms, irrespective of the initiating insult.4 In animal models, a reduction in nephron mass exposes the remaining nephrons to adaptive haemodynamic changes that sustain renal function initially but are detrimental in the long term.5

Figure 1.

Continuum of renal disease (anticlockwise model) (CRF=chronic renal failure; ESRD=end stage renal disease; GFR=glomerular filtration rate)

Early detection

Renal disease is often progressive once glomerular filtration rate falls by 25% of normal. Early detection is important to prevent further injury and progressive loss of renal function.

Patients at high risk (box B2) should undergo evaluation for markers of kidney damage (albuminuria (box B3), abnormal urine sediment, elevated serum creatinine) and for renal function (estimation of glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine) initially and at periodic intervals depending on the underlying disease process and stage of renal disease. Potentially reversible causes (box B4) should be identified and effectively treated if a sudden decline in renal function is observed.

Box 2.

Risk factors for chronic renal disease

- Age

- Diabetes*

- Hypertension*

- Family history of renal disease

- Renal transplant

- Diabetes*

- Hypertension*

- Autoimmune diseases

- Primary glomerulopathies

- Systemic infections

- Nephrotoxic agents

- Persistent activity of underlying disease

- Persistent proteinuria

- Elevated blood pressure*

- Elevated blood glucose*

- High protein/phosphate diet

- Hyperlipidaemia*

- Hyperphosphataemia

- Anaemia

- Cardiovascular disease

- Smoking*

- Other factors: elevated angiotensin II, hyperaldosteronism, increased endothelin, decreased nitric oxide

Box 3.

Definition of urinary albumin or protein excretion

- Normal albumin excretion: <30 mg/24 hours

- Microalbuminuria: 20-200 μg/min or 30-300 mg/24 hour or

- in men—urine albumin/creatinine 2.5-25 mg/mmol

- in women—urine albumin/creatinine 3.5-35 mg/mmol

- Macroalbuminuria (overt proteinuria): >300 mg/24 hour

- Nephrotic range proteinuria: >3 g/24 hour

Box 4.

Potentially reversible causes of worsening renal function

- Effective circulatory volume depletion: dehydration, heart failure, sepsis

- Obstruction: urinary tract obstruction

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- Toxic causes: nephrotoxic or radiocontrast agents

Diabetes

Diabetes is a common cause of chronic renal failure and accounts for a large part of the growth in end stage renal disease in North America.w3 Effective control of blood glucose and blood pressure reduces the renal complications of diabetes.

Meticulous control of blood glucose has been conclusively shown to reduce the development of microalbuminuria by 35% in type 1 diabetes (diabetes control and complications trial)6 and in type 2 diabetes (United Kingdom prospective diabetes study).7 Other studies have indicated that glycaemic control can reduce the progression of diabetic renal disease.8 Adequate control of blood pressure with a variety of antihypertensive agents, including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, has been shown to delay the progression of albuminuria in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.9,10 Recently, angiotensin receptor blockers have been shown to have renoprotective effects in both early and late nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes.11–13 Box B5 shows strategies for managing diabetic nephropathy.

Box 5.

Management strategies for diabetic nephropathy

- Initial stage (normal albumin excretion, <30 mg/24 hours):

- Optimal glycaemic control (haemoglobin A1c <7%)

- Target blood pressure <130/80 mm Hg

- Monitor urinary albumin excretion

- Incipient nephropathy (microalbuminuria, 30-300 mg/24 hour or 20-200 μg/min):

- Optimal glycaemic control (haemoglobin A1c <7%)

- Target blood pressure <125/75 mm Hg

- Control urinary albumin excretion, irrespective of blood pressure

- Angiotensin inhibition

- Overt nephropathy (albumin excretion >300):

- Optimal glycaemic control (haemoglobin A1c <7%)

- Target blood pressure <125/75 mm Hg

- Control urinary protein excretion

- Angiotensin inhibition, irrespective of blood pressure

- Avoid malnutrition

- Modest protein restriction, in selected groups

- Nephropathy with renal dysfunction:

- Optimal glycaemic control; avoid frequent hypoglycaemia

- Target blood pressure <125/75 mm Hg

- Angiotensin inhibition

- Watch for hyperkalaemia

- Avoid malnutrition; consider protein and phosphate restriction

- End stage renal disease:

- Renal replacement—transplantation or dialysis

- Monitor for hyperkalaemia

- Hold angiotensin inhibition (when glomerular filtration <15 ml/min) in selected patients

Hypertension

Hypertension is a well established cause, a common complication, and an important risk factor for progression of renal disease. Controlling hypertension is the most important intervention to slow the progression of renal disease.w4

Any antihypertensive agents may be appropriate, but angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors are particularly effective in slowing progression of renal insufficiency in patients with and without diabetes by reducing the effects of angiotensin II on renal haemodynamics, local growth factors, and perhaps glomerular permselectivity.9 w5 Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers have also been shown to retard progression of renal insufficiency in patients with type 2 diabetes. Recently, angiotensin receptor blockers (irbesartan and losartan) have been shown to have a renoprotective effect in diabetic nephropathy, independent of reduction in blood pressure.11–13 Early detection and effective treatment of hypertension to target levels is essential (box B6). The benefit of aggressive control of blood pressure is most pronounced in patients with urinary protein excretion of >3 g/24 hours.w4

Box 6.

Target blood pressure in renal diseasew6

- Blood pressure of <130/85 mm Hg in all patients with renal disease

- Blood pressure of <125/75 mm Hg in patients with proteinuric renal disease (urinary protein excretion ⩾1 g/24 hours)

Proteinuria

Proteinuria, previously considered a marker of renal disease, is itself pathogenic and is the single best predictor of disease progression.w7 Reducing urinary protein excretion slows the progressive decline in renal function in both diabetic and non-diabetic kidney disease.

Angiotensin blockade with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers is more effective at comparable levels of blood pressure control than conventional antihypertensive agents in reducing proteinuria, decline in glomerular filtration rate, and progression to end stage renal disease.11–14 w5 w8-w10

Intake of dietary protein

The role of dietary protein restriction in chronic renal disease remains controversial.15,16 w4 The largest controlled study initially failed to find an effect of protein restriction,17 but secondary analysis based on achieved protein intake suggested that a low protein diet slowed the progression. However, early dietary review is necessary to ensure adequate energy intake, maintain optimal nutrition, and avoid malnutrition.

Dyslipidaemia

Lipid abnormalities may be evident with only mild renal impairment and contribute to progression of chronic renal disease and increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. A meta-analysis of 13 controlled trials showed that hydroxymethyl glutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) decreased proteinuria and preserved glomerular filtration rate in patients with renal disease, an effect not entirely explained by reduction in blood cholesterol.18

Phosphate and parathyroid hormone

Hyperparathyroidism is one of the earliest manifestations of impaired renal function,19 and minor changes in bones have been found in patients with a glomerular filtration rate of 60 ml/min.20 Precipitation of calcium phosphate in renal tissue begins early, may influence the rate of progression of renal disease, and is closely related to hyperphosphataemia and calcium phosphate (Ca×P) product. Precipitation of calcium phosphate should be reduced by adequate fluid intake, modest dietary phosphate restriction, and administration of phosphate binders to correct serum phosphate. Dietary phosphate should be restricted before the glomerular filtration rate falls below 40 ml/min and before the development of hyperparathyroidism. The use of vitamin D supplements during chronic renal disease is controversial.

Smoking

Smoking, besides increasing the risk of cardiovascular events, is an independent risk factor for development of end stage renal disease in men with kidney disease.21 Smoking cessation alone may reduce the risk of disease progression by 30% in patients with type 2 diabetes.22

Anaemia

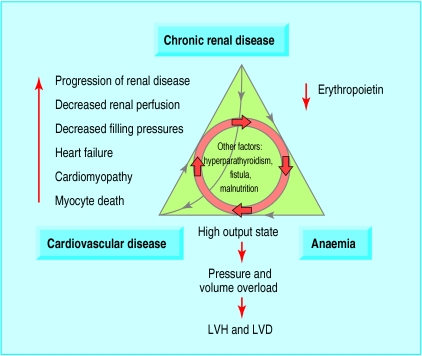

Anaemia of chronic renal disease begins when the glomerular filtration rate falls below 30-35% of normal and is normochromic and normocytic. This is primarily caused by decreased production of erythropoietin by the failing kidney,23 but other potential causes should be considered. Whether anaemia accelerates the progression of renal disease is controversial. However, it is independently associated with the development of left ventricular hypertrophy and other cardiovascular complications in a vicious cycle (fig 2).24

Figure 2.

Perpetuating triad of chronic kidney disease, anaemia, and cardiovascular disease (LVH=left ventricular hypertrophy; LVD=left ventricular dilatation)

Treatment of anaemia with recombinant human erythropoietin may slow progression of chronic renal disease but requires further study. Treatment of anaemia results in partial regression of left ventricular hypertrophy in both patients with pre-end stage renal disease and patients receiving dialysis and has reduced the frequency of heart failure and hospitalisation among patients receiving dialysis.25,26

Both National Kidney Foundation and European best practice guidelines recommend evaluation of anaemia when haemoglobin is <11 g/dl and consideration of recombinant human erythropoietin if haemoglobin is consistently <11 g/dl to maintain a target haemoglobin of >11 g/dl.27,28

Prevention or attenuation of complications and comorbidities

Malnutrition

The prevalence of hypoalbuminaemia is high among patients beginning dialysis, is of multifactorial origin, and is associated with poor outcome. Hypoalbuminaemia may be a reflection of chronic inflammation rather than of nutrition in itself. Spontaneous intake of protein begins to decrease when the glomerular filtration rate falls below 50 ml/min. Progressive decline in renal function causes decreased appetite, thereby increasing the risk of malnutrition. Hence early dietary review is important to avoid malnutrition. Adequate dialysis is also important in maintaining optimal nutrition.

Cardiovascular disease

The prevalence, incidence, and prognosis of clinical cardiovascular disease in renal failure is not known with precision, but it begins early and is independently associated with increased cardiovascular and all cause mortality.w11 Both traditional and uraemia specific risk factors (anaemia, hyperphosphataemia, hyperparathyroidism) contribute to the increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease.29 Cardiac disease, including left ventricular structural and functional disorders, is an important and potentially treatable comorbidity of early kidney disease.

No specific recommendations exist for either primary or secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic renal disease. Current practice is mostly derived from studies in patients with diabetic or non-renal disease. At present, in the absence of evidence, clinical judgment indicates effective control of modifiable and uraemia specific risk factors at an early stage of renal disease; definitive guidelines for intervention await well designed, adequately powered prospective studies.

Preparing patient for renal replacement treatment

Integrated care by the primary care physician, nephrologist, and renal team from an early stage is vital to reduce the overall morbidity and mortality associated with chronic renal disease. Practical points helpful at this stage of renal disease include

Patients should be referred to a nephrologist before serum creatinine is 150-180 μmol/l

Patients receiving comprehensive care by the renal team have shown slower rates of decline in renal function, greater probability of starting dialysis with higher haemoglobin, better calcium control, a permanent access, and a greater likelihood of choosing peritoneal dialysisw12

Patients with progressive renal failure should be educated to save vessels of the non-dominant arm for future haemodialysis access; they should have a permanent vascular access (preferably arteriovenous fistula) created when the glomerular filtration rate falls below 25 ml/min or renal replacement treatment is anticipated within a year

Patients starting dialysis at relatively higher levels of residual renal function (early starts) have better solute clearance, less malnutrition, better volume control, and less morbidity and mortality than patients starting at traditional low levels of renal function (late starts).w13

Conclusion

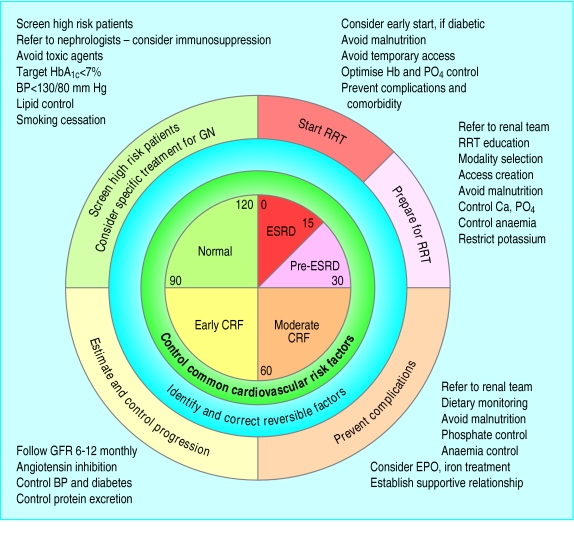

Chronic renal failure represents a critical period in the evolution of chronic renal disease and is associated with complications and comorbidities that begin early in the course of the disease. These conditions are initially subclinical but progress relentlessly and may eventually become symptomatic and irreversible. Early in the course of chronic renal failure, these conditions are amenable to interventions with relatively simple treatments that have the potential to prevent adverse outcomes. Fig 3 summarises strategies for effective management of chronic renal disease. By acknowledging these facts, we have an excellent opportunity to change the paradigm of management of chronic renal failure and improve patient outcomes.

Additional educational resources

Tomson CRV. Recent advances: nephrology. BMJ 2000;320:98-101

Mason PD, Pusey CD. Glomerulonephritis: diagnosis and treatment. BMJ 1994;309:1557-63

Walker R. Recent advances: general management of end stage renal disease. BMJ 1997;315:1429-32

Ifudu O. Care of patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1054-62

Remuzzi G, Schieppati A, Ruggenenti P. Clinical practice: nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1145-51

National Kidney Foundation—K/DOQI. Clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 2002;39(suppl 1):S1-266

Patient information

Kidney School (www.kidneyschool.org)—an interactive, web based program designed to help people learn what they need to know to understand renal disease and its treatment, adjust to renal disease, make good medical choices, and live as fully as possible

Doc-To-Me (www.doctome.com)—presents concise, informative, and authoritative pre-end stage renal disease lectures: “Staying healthy with bad kidneys”

Kidney Incorporated (www.hdialysis.com)—provides general information about kidneys, pre-end stage renal disease care, and dialysis treatment

Figure 3.

Strategies for active management of chronic renal disease (BP=blood pressure; Ca=calcium; CRF=chronic renal failure; EPO=erythropoietin; ESRD=end stage renal disease; GN=glomerulonephritis; GFR=glomerular filtration rate; Hb=haemoglobin; PO4=phosphate; RRT=renal replacement treatment)

Supplementary Material

Table.

Stages of renal dysfunction (adapted from National Kidney Foundation—K/DOQI)2

| Stage

|

Description

|

Creatinine clearance (∼GFR) (ml/min/1.73 m2)

|

Metabolic consequences

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal or increased GFR—people at increased risk (box B2) or with early renal damage | >90 | |

| 2 | Early renal insufficiency | 60-89* | Concentration of parathyroid hormone starts to rise (GFR∼60-80) |

| 3 | Moderate renal failure (chronic renal failure) | 30-59 | Decrease in calcium absorption (GFR<50) Lipoprotein activity falls Malnutrition Onset of left ventricular hypertrophy Onset of anaemia (erythropoietin deficiency) |

| 4 | Severe renal failure (pre-end stage renal disease) | 15-29 | Triglyceride concentrations start to rise Hyperphosphataemia Metabolic acidosis Tendency to hyperkalaemia |

| 5 | End stage renal disease (uraemia) | <15 | Azotaemia develops |

GFR=glomerular filtration rate.

May be normal for age.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Additional references appear on bmj.com

References

- 1.Jones C, McQuillan G, Kusek J, Eberhardt M, Herman W, Coresh J, et al. Serum creatinine levels in the US population: third national health and nutrition examination survey [correction appears in Am J Kidney Dis 2000;35:178] Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:992–999. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(98)70074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Kidney Foundation—K/DOQI. Clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(suppl 1):S1–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walser M. Assessing renal function from creatinine measurements in adults with chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32:1–22. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9669420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Remuzzi G, Bertani T. Pathophysiology of progressive nephropathies. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1448–1456. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811123392007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner BM, Meyer TW, Hostetter TH. Dietary protein intake and the progressive nature of kidney disease: the role of hemodynamically mediated glomerular injury in the pathogenesis of progressive glomerular sclerosis in aging, renal ablation, and intrinsic renal disease. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:652–659. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198209093071104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) Research Group. Effect of intensive therapy on the development and progression of nephropathy in the DCCT. Kidney Int. 1995;47:1703–1720. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317:703–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang P, Lau J, Chalmers T. Meta-analysis of the effects of intensive blood-glucose control on late complications of type I diabetes. Lancet. 1993;341:1306–1309. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90816-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis E, Hunsicker L, Bain R, Rhode R. The effect of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition on diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1456–1462. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311113292004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parving H-H, Osterby R, Anderson P, Hsuech W. Diabetic nephropathy. In: Brenner B, editor. The kidney. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1996. pp. 1864–1892. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parving H-H, Lehnert H, Brochner-Mortensen J, Gomis R, Anderson S, Arner P.for the Irbesartan in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Microalbuminuria Study Group. The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 Diabetes N Engl J Med 2001345870–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, et al. for the Collaborative Study Group. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes N Engl J Med 2001345851–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving H-H, et al. for the RENAAL Study Investigators. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy N Engl J Med 2001345861–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mogensen CE, Neldam I, Tikkanen I, Oren S, Viskoper R, Watts RW, et al. Randomised controlled trial of dual blockade renin-angiotensin system in patients with hypertension, microalbuminuria, and non-insulin dependent diabetes: the candesartan and lisinopril microalbuminuria (CALM) study. BMJ. 2000;321:1440–1444. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7274.1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klahr S. Is there still a role for a diet very low in protein, with or without supplements, in the management of patients with end-stage renal disease? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1996;5:384–387. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199607000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levey AS, Adler S, Caggiula AW, England BK, Greene T, Hunsicker LG, et al. Effects of dietary protein restriction on the progression of advanced renal disease in the modification of diet in renal disease study. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;27:652–663. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Effects of diet and antihypertensive therapy on creatinine clearance and serum creatinine in the modification of diet in renal disease study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:556–566. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V74556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fried LF, Orchard TJ, Kasiske BL. Effect of lipid reduction on the progression of renal disease: a meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2001;59:260–269. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez I, Saracho R, Montenegro J, Llach F. The importance of dietary calcium and phosphorus in the secondary hyperparathyroidism of patients with early renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:496–502. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coen G, Mazzaferro S, Ballant P, Sardella D, Chicca S, Manni M, et al. Renal bone disease in 76 patients with varying degrees of predialysis chronic renal failure: a cross-sectional study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:813–819. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a027404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orth S, Stockmann A, Conradt C, Ritz E, Ferro M, Kreusser W, et al. Smoking as a risk factor for end-stage renal failure in men with primary renal disease. Kidney Int. 1998;54:926–931. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritz E, Ogata H, Orth SR. Smoking a factor promoting onset and progression of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Metab. 2000;26(suppl 4):54–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eschbach JW. The anemia of chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 1989;35:134–148. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD, Kent GM, Murray DC, Barre PE. The impact of anemia on cardiomyopathy, morbidity and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28:53–61. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(96)90130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Portoles J, Torralbo A, Martin P, Rodrigo J, Herrero J, Barrientos A. Cardiovascular effects of recombinant human erythropoietin in predialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:541–548. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90335-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eschbach JW, Aquiling T, Haley NR, Fan MH, Blagg CR. The long-term effects of recombinant human erythropoietin on the cardiovascular system. Clin Nephrol. 1992;38:S98–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Kidney Foundation—Dialysis Outcomes Quality Initiative. Guidelines for the treatment of anemia of chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;30(suppl 3):S150–S191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.European best practice guidelines for the management of anaemia in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14(suppl 5):1–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foley RN, Parfrey PS. Cardiac disease in chronic uremia: clinical outcomes and risk factors. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 1997;4:234–238. doi: 10.1016/s1073-4449(97)70032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.