Abstract

Background

Patients with pancreatic cancer have an unfavorable 5-year survival rate of approximately 3% due to diagnosis occurring at advanced stages. Prior research has proposed vitamin C may have a therapeutic and preventative role in pancreatic cancer.

Methods

A Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant national database was utilized to assess pancreatic cancer risk in patients with or without a history of vitamin C intake. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes were used, specifically the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10) and International Classification of Diseases, Nineth Edition (ICD-9), between January 2010 and December 2020. Patients were matched, and statistical analyses were implemented. Chi-squared, logistic regression, and odds ratio were used to test for significance and to estimate relative risk.

Results

A total of 83,941 patients were identified as utilizing prescribed vitamin C. Subsequent matching by Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score and age resulted in two groups of 50,384 patients. The incidence of pancreatic cancer was 243 (0.48%) in the group with a history of vitamin C intake compared to 442 (0.88%) in the control group. The difference was statistically significant by P < 3.174 × 10-14 with an odds ratio of 0.548 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.468 - 0.641). Overall, patients without vitamin C prescription had an increased prevalence of pancreatic cancer throughout all ages and regions of the United States when compared to those with a vitamin C prescription. In addition, healthcare costs were higher in total for the control group when compared to the experimental group.

Conclusions

This retrospective cohort study found a statistically significant correlation between vitamin C and subsequent incidence of pancreatic cancer. Further studies are recommended to explore vitamin C’s redox and cofactor activity in the context of preventing and possibly treating pancreatic cancer, as well as consider pancreatic cancer lifestyle risk factors such as smoking.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, Vitamin C, Risk factors

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the seventh leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [1]. In the United States, approximately 30,000 individuals are newly diagnosed with pancreatic cancer each year, with a higher incidence in men when compared to women. Accounting for all stages of cancer, the 5-year survival rate is 4%, which can be attributed to the fact that once this cancer presents it is usually at a very advanced stage. In fact, metastatic disease is present in 80% of newly diagnosed pancreatic cancer cases [2]. Even though treating pancreatic cancer with surgical resection improves the 5-year survival rate to 40%, most patients are elderly individuals whose comorbidities decrease the probability of a favorable outcome. Not to mention most of the patients are not eligible for surgical intervention due to the presence of metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis [2, 3].

As a result, early diagnosis as well as prevention is important in reducing the incidence of pancreatic cancer. Currently, prevention focuses on diminishing known modifiable risk factors for pancreatic cancer development such as long-term smoking, obesity, and diabetes mellitus [2, 4, 5]. Unfortunately, many risk factors are non-modifiable such as advanced age, male sex, low socioeconomic status, and Ashkenazi Jewish heritage [2, 5, 6].

Current literature suggests that vitamin C decreases low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and cholesterol significantly, not only reducing the risk for cardiovascular disease but also targeting one of the modifiable risk factors for pancreatic cancer [7]. Unsurprisingly, vitamin C is an essential micronutrient that serves various important biological functions. These functions include, but are not limited to, enhancing the immune system function via natural killer, T cell, and monocyte activation. Additionally, vitamin C serves as an enzyme cofactor for collagen and carnitine synthesis and serves as a gene regulator via its effect on transcription factors [8-13].

In addition, vitamin C is also used to prevent and treat a multitude of ophthalmological, neurological, and cardiovascular conditions ranging from glaucoma to cerebrovascular accidents [14-17]. Regarding its anticarcinogenic role, it has been hypothesized that vitamin C has anticarcinogenic properties attributed to its ability to neutralize free radicals, role as a gene expression regulator, and ability to induce the degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor, hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), which is essential for tumor cells to survive in hypoxic conditions. The effects of vitamin C on cancer development are dependent on whether the route of administration is oral or intravenous, as well as the presence of vitamin C transporters in malignant cells. Some tumor cells have an increased expression of sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2 (SVCT2) and/or glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1), which are transporters that allow for increased absorption of vitamin C when compared to normal cells [18]. Especifically, pharmacological doses of vitamin C may be a promising therapeutic option for pancreatic cancer. In vivo treatment with ascorbate showed to inhibit viability in all pancreatic cells by inducing caspase-independent cell death that was associated with autophagy. However, ascorbate had no effect on an immortalized pancreatic ductal epithelial cell line [19]. More research is therefore required to explore if these results can be replicated in individuals with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, as a cell line is not equivalent to a complex organism such as the human body. In fact, current research has already begun exploring the safety and synergistic effect of intravenous vitamin C in the context of pancreatic cancer treatment. A phase I clinical trial demonstrated that vitamin C is well tolerated when combined with the chemotherapeutic agent, gemcitabine, in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma [20]. Not to mention, the same clinical trial hypothesized that vitamin C may act as a pro drug to cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents by aiding in the delivery of hydrogen peroxide to pancreatic tumors, resulting in oxidative stress and tumor cell destruction [20]. It is important to note that pharmacological doses of vitamin C must be administered intravenously for plasma concentrations to be high enough to reach antitumor activity based on pre-clinical studies [21]. In summary, current research has focused on the potential therapeutic role of intravenous vitamin C in the context of pancreatic cancer. However, further research is needed to explore whether or not pharmacological doses of vitamin C could be used to prevent or delay the development of pancreatic cancer in high-risk populations.

In turn, the aim of our study was to explore prevention of pancreatic cancer development with a focus on vitamin C.

Materials and Methods

Data extraction and analysis

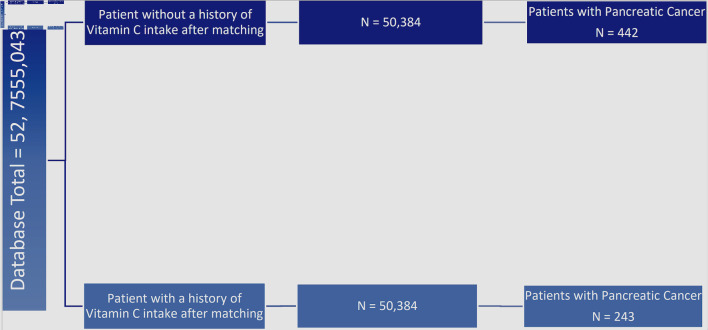

The Humana Health Insurance Portability and Accountability (HIPAA) compliant national database was used and granted accessed by Holy Cross Health, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, solely for academic research purposes. A retrospective analysis was conducted from January 2010 to December 2020 using the International Classification of Disease Ninth and 10th Revision (ICD-9, ICD-10) codes for pancreatic cancer and National Drug Codes (NDC) and Generic Drug codes for vitamin C. From the 52,755,043 HIPAA compliant patient records, 83,941 patients were identified as actively being prescribed vitamin C. Subsequent matching by Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score and age resulted in two groups in each the experimental and control group of 50,384 patients as seen in Figure 1. A statistical analysis was then conducted to evaluate the number of patients from each group that developed pancreatic cancer. In turn, the development of pancreatic cancer was the primary outcome measure of this study. Statistical analysis was performed using the PearlDiver statistical analysis software; specifically, we performed Chi-squared tests, calculated odds ratios, and estimated relative risk. Further analysis encompassed data stratification of the patient demographics in the control and experimental groups. Moreover, the inclusion criteria included active status in the database for at least 8 years and verified prescription of pharmacological doses of vitamin C. Of note, the database used for this study did not delineate the exact doses of vitamin C prescribed.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of incidence of pancreatic cancer in patients with and without history of prescribed vitamin C. Left side: total patients in the database (n = 52,755,043). First and second column from the left: evaluation of incidence of pancreatic cancer in patients without a prior history of being prescribed vitamin C (dark blue, n = 50,384) and with prior prescription of vitamin C (light blue, n = 50,384). Third column from left: additional stratification and matching were done based on patient comorbidities and age, illustrating the incidence of pancreatic cancer in matched groups with and without vitamin C prescription (light blue and dark blue respectively, n = 243 and n = 442). The difference between experimental and control group was statistically significant by P < 3.174 × 10-14 with an odds ratio of 0.548 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.468 - 0.641).

Literature review

The goal of the literature review was to gather data pertaining to any relationships between vitamin C and pancreatic cancer. The review was conducted using PubMed as the main database and used the keywords: “pancreatic cancer”, “ascorbic acid”, “vitamin C”. Currently available research tends to agree with the hypothesis that vitamin C may decrease the risk of developing pancreatic cancer. However, two studies stated that there was no association between vitamin C and pancreatic cancer, and one stated that there was insufficient evidence to formulate a conclusion. In terms of gaps in the current literature, there is a need to conduct a study with a population encompassing more than one US state.

IRB approval

This study was exempt from IRB approval because all data were obtained from a database that provided deidentified patient information, and the declaration of ethical compliance with human study is not applicable.

Results

Patients with history of prescribed vitamin C use had a decreased incidence of pancreatic cancer when compared to the control group

The incidence of pancreatic cancer was 243 (0.48%) in the group with a history of vitamin C intake compared to 442 (0.88%) in the control group as shown in Figure 1.

The difference was statistically significant by P < 3.174 × 10-14 with an odds ratio of 0.548 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.468 - 0.641).

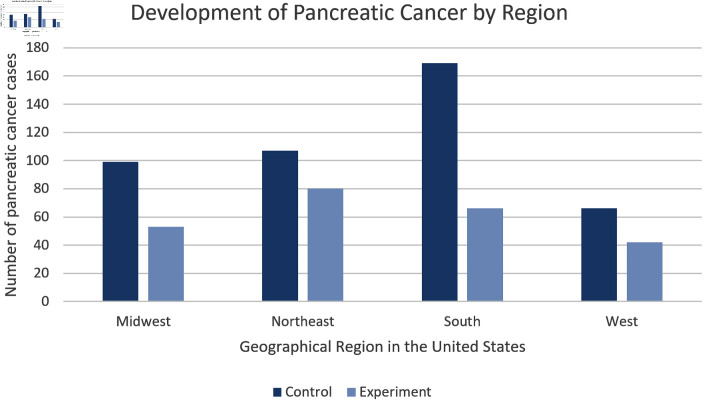

Patients with history of prescribed vitamin C use had a decreased incidence of pancreatic cancer across all regions of the United States when compared to the control group

We stratified the data based on region of residence within the United States. Specifically, we assessed the rate of pancreatic cancer development in the Midwest, Northeast, South, and West. In all regions, results consistently showed a reduced rate of pancreatic cancer within the experimental group. As seen in Figure 2, throughout all regions individuals within the control group were at least 1.34 times more likely to be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

Figure 2.

Regional Distribution. This bar chart shows the number of patients with pancreatic cancer sorted by United States region without prior history of prescribed vitamin C (dark blue) and with prior history of prescribed vitamin C (light blue). Patients from the control group located in the southern region display the highest incidence of pancreatic cancer in both groups.

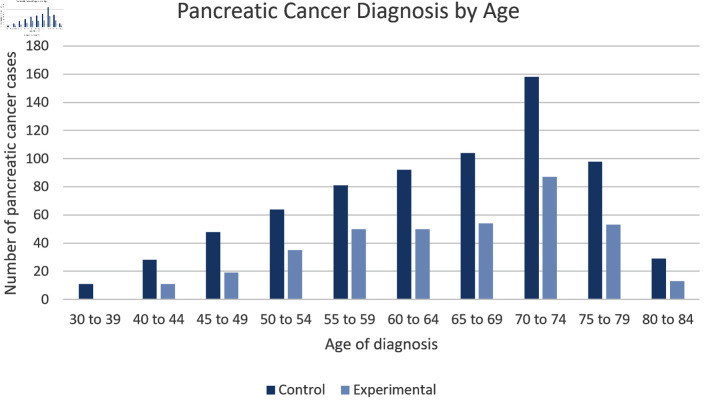

Patients with history of prescribed vitamin C use had a decreased incidence of pancreatic cancer across all age groups when compared to the control group

As seen in Figure 3 and Table 1, the data were also analyzed based on age of diagnosis. As expected, the highest incidence of pancreatic cancer was seen from ages 70 - 74. Moreover, patients from the control group consistently had a higher incidence of pancreatic cancer throughout all age groups when compared to the experimental group.

Figure 3.

Age Distribution. Incidence of pancreatic cancer is sorted by age in patients without history of prescribed vitamin C (dark blue) and no history of prescribed vitamin C (light blue) groups. Patients in the experimental group showed consistently lower numbers of pancreatic cancer cases in all age ranges and the number of pancreatic cancer cases peaked in the age range 70 - 74 for both groups. The difference between experimental and control group was statistically significant by P < 3.174 × 10-14 with an odds ratio of 0.548 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.468 - 0.641).

Table 1. Summary of Patient Factors.

| Control and PC | Experimental and PC | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 64.17 ± 10.99 | 64.93 ± 10.04 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 194 (43.9) | 150 (61.7) |

| Male | 248 (56.1) | 93 (38.3) |

Comparison of baseline characteristics of PC patients according to PC patients with/without vitamin C prescription (experimental and control group respectively). Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or frequencies (percentages). PC: pancreatic cancer.

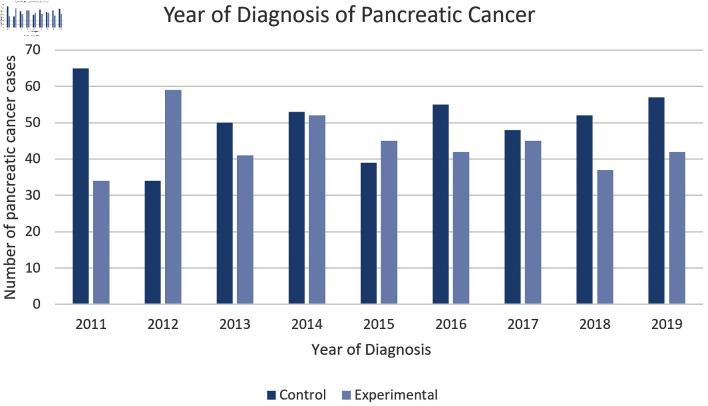

Furthermore, Figure 4 showcases how we assessed the incidence of pancreatic cancer diagnosis per year dating from 2011 to 2019. We found that there was a higher incidence within the control group except for the years 2012 and 2015.

Figure 4.

Incidence of pancreatic cancer by year. This figure illustrates the incidence of pancreatic cancer in both the experimental and control group by year. The control group was shown to have the highest incidence of pancreatic cancer in 6 out of the 8 years. The difference between experimental and control group was statistically significant by P < 3.174 × 10-14 with an odds ratio of 0.548 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.468 - 0.641).

Patients with history of prescribed vitamin C use who were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer had longer length of stay (LOS) in the hospital but decreased healthcare costs when compared to the control group.

Financial data and LOS were also analyzed utilizing matched data. On average, patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in the experimental group stayed 0.71 more days in the hospital than pancreatic cancer patients in the control group, with the longest LOS being in the Northeast region of the United States for both groups. However, pancreatic cancer patients in the control group paid 17,450 dollars more on average. In terms of the geographical region with higher costs, Northeast region of the United States had the highest total paid for the experimental group and the Southern region for the control group.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study a statistically significant correlation was found between vitamin C and subsequent incidence of pancreatic cancer. A possible explanation for these results may relate to vitamin C’s ability to reduce serum LDL and triglycerides [7]. Vitamin C can reduce reactive oxygen species leading to lower plasma lipid peroxide levels which halts oxidative modification of LDLs. Ultimately, this interaction results in a prompter removal of LDL from the blood via catabolic pathways [22, 23].

Moreover, vitamin C may have antineoplastic properties at pharmacological doses. Recent literature has proposed that breast cancer cells consume vitamin C via SVCT2 and GLUTs, which can be damaging to the cell in pharmacological or excessive doses. Vitamin C damages the cell by producing hydrogen peroxide extracellularly, in turn leading to oxidative stress and contributing to cell death [19, 24]. Unlike cancer cells, non-neoplastic breast cells do not absorb as much vitamin C due to a lesser amount of cell surface transporters. It is important to conduct similar research with pancreatic cells, as this is a promising mechanism that could be exploited to eventually utilize vitamin C as a component of a mainstay treatment for pancreatic cancer.

In addition, the data also supported lower healthcare costs as well as a longer LOS in the experimental group. We hypothesize this particular result may be product of confounding variables such as socioeconomic status and lifestyle choices such as smoking. In 2016, The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reported the rate of inpatient stays for each US census division and found that in every single region the individuals with the lower income had the highest rate of inpatient stays [25]. Moreover, it is important to note that these differences in LOS may be related to trust in the healthcare system and personal decisions to pursue palliative care at home [26].

In terms of limitations, our study did not stratify data based on ethnicity or race as the database we utilized does not contain that information. Since this may be a possible confounding variable, it limits the validity of the study. Moreover, the database also did not report the route of administration of vitamin C or lifestyle factors such as smoking as well as family history. In turn, future research will likely be necessary to confirm our findings by addressing these limitations.

Conclusions

This study shows a statistically significant correlation between history of prescribed vitamin C use and a decreased incidence of pancreatic cancer. There is a need for further research to understand the role of vitamin C in the context of pancreatic cancer prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Holy Cross Hospital and Nova Southeastern University, Dr. Kiran C. Patel College of Allopathic Medicine. K. Takabe was supported by US National Institutes of Health (R37CA248018, R01CA250412, R01CA251545, R01EB029596), as well as US Department of Defense BCRP grants (W81XWH-19-1-0674 and W81XWH-19-1-0111).

Funding Statement

Grant support: Broward Community Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this paper have no conflict of interest to report.

Informed Consent

The informed consent was exempted by the IRB because of the database study.

Author Contributions

Maria Pereira is the first author and is responsible for data analysis, figures, literature review, and manuscript writing. Matthew Cardeiro is responsible for database extraction and analysis, manuscript writing and editing. Lexi Frankel and Bryan Greenfield are responsible for supplemental editing. Authors Omar Rashid, corresponding author, and Kazuaki Takabe are responsible for manuscript writing, editing, and data analysis.

Data Availability

Data extracted from the PearlDiver national database are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HIF-1

hypoxia-inducible factor 1

- SVCT2

sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2

- GLUT1

glucose transporter 1

- HIPAA

Humana Health Insurance Portability and Accountability

- ICD-9

ICD-10, the International Classification of Disease Ninth and 10th Revision

- NDC

National Drug Codes

- CCI

Charlson Comorbidity Index

- LOS

length of stay

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

References

- 1.Rawla P, Sunkara T, Gaduputi V. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: global trends, etiology and risk factors. World J Oncol. 2019;10(1):10–27. doi: 10.14740/wjon1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeo TP, Hruban RH, Leach SD, Wilentz RE, Sohn TA, Kern SE, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. et al. Pancreatic cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 2002;26(4):176–275. doi: 10.1067/mcn.2002.129579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGuigan A, Kelly P, Turkington RC, Jones C, Coleman HG, McCain RS. Pancreatic cancer: A review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(43):4846–4861. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i43.4846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subhan M, Saji Parel N, Krishna PV, Gupta A, Uthayaseelan K, Uthayaseelan K, Kadari M. Smoking and pancreatic cancer: smoking patterns, tobacco type, and dose-response relationship. Cureus. 2022;14(6):e26009. doi: 10.7759/cureus.26009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai HJ, Chang JS. Environmental risk factors of pancreatic cancer. J Clin Med. 2019;8(9):1427. doi: 10.3390/jcm8091427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Midha S, Chawla S, Garg PK. Modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors for pancreatic cancer: A review. Cancer Lett. 2016;381(1):269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McRae MP. Vitamin C supplementation lowers serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides: a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials. J Chiropr Med. 2008;7(2):48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jcme.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dosedel M, Jirkovsky E, Macakova K, Krcmova LK, Javorska L, Pourova J, Mercolini L. et al. Vitamin C-sources, physiological role, kinetics, deficiency, use, toxicity, and determination. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):615. doi: 10.3390/nu13020615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carr AC, Maggini S. Vitamin C and immune function. Nutrients. 2017;9(11):1211. doi: 10.3390/nu9111211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pawlowska E, Szczepanska J, Blasiak J. Pro- and antioxidant effects of vitamin C in cancer in correspondence to its dietary and pharmacological concentrations. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:7286737. doi: 10.1155/2019/7286737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murad S, Grove D, Lindberg KA, Reynolds G, Sivarajah A, Pinnell SR. Regulation of collagen synthesis by ascorbic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(5):2879–2882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.2879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brabson JP, Leesang T, Mohammad S, Cimmino L. Epigenetic Regulation of Genomic Stability by Vitamin C. Front Genet. 2021;12:675780. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.675780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikkelsen SU, Gillberg L, Lykkesfeldt J, Gronbaek K. The role of vitamin C in epigenetic cancer therapy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;170:179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen GC, Lu DB, Pang Z, Liu QF. Vitamin C intake, circulating vitamin C and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(6):e000329. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valero MP, Fletcher AE, De Stavola BL, Vioque J, Alepuz VC. Vitamin C is associated with reduced risk of cataract in a Mediterranean population. J Nutr. 2002;132(6):1299–1306. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.6.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li S, Jakobs TC. Vitamin C protects retinal ganglion cells via SPP1 in glaucoma and after optic nerve damage. Life Sci Alliance. 2023;6(8):e202301976. doi: 10.26508/lsa.202301976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kocot J, Luchowska-Kocot D, Kielczykowska M, Musik I, Kurzepa J. Does vitamin C influence neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric disorders? Nutrients. 2017;9(7):659. doi: 10.3390/nu9070659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vissers MCM, Das AB. Potential Mechanisms of Action for Vitamin C in Cancer: Reviewing the Evidence. Front Physiol. 2018;9:809. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du J, Martin SM, Levine M, Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Wang SH, Taghiyev AF. et al. Mechanisms of ascorbate-induced cytotoxicity in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(2):509–520. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welsh JL, Wagner BA, van't Erve TJ, Zehr PS, Berg DJ, Halfdanarson TR, Yee NS. et al. Pharmacological ascorbate with gemcitabine for the control of metastatic and node-positive pancreatic cancer (PACMAN): results from a phase I clinical trial. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71(3):765–775. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2070-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padayatty SJ, Sun H, Wang Y, Riordan HD, Hewitt SM, Katz A, Wesley RA. et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics: implications for oral and intravenous use. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(7):533–537. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balkan J, Dogru-Abbasoglu S, Aykac-Toker G, Uysal M. Serum pro-oxidant-antioxidant balance and low-density lipoprotein oxidation in healthy subjects with different cholesterol levels. Clin Exp Med. 2004;3(4):237–242. doi: 10.1007/s10238-004-0031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polidori MC, Mecocci P, Levine M, Frei B. Short-term and long-term vitamin C supplementation in humans dose-dependently increases the resistance of plasma to ex vivo lipid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;423(1):109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roa FJ, Pena E, Gatica M, Escobar-Acuna K, Saavedra P, Maldonado M, Cuevas ME. et al. Therapeutic use of vitamin C in cancer: physiological considerations. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:211. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman WJ, Weiss AJ, Heslin KC. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): 2006. Overview of U.S. Hospital Stays in 2016: Variation by Geographic Region. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghosh AK, Geisler BP, Ibrahim S. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic variations in hospital length of stay: A state-based analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100(20):e25976. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data extracted from the PearlDiver national database are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.