In this article, based on a talk given to a recent meeting on global health, Julio Frenk and Octavio Gómez-Dantés argue that, although there are many threats inherent in globalisation, improving health is a unifying activity. They suggest that “exchange, evidence, and empathy” should characterise international activities to improve health and health care for all the world's people

In the aftermath of the events of 11 September Britain's prime minister, Tony Blair, reminded us of what he called “the fragility of our frontiers in the face of the world's new challenges” (Labour Party Conference, Brighton, October 2001). This shift of human affairs from the restricted frame of the nation state to the vast theatre of planet earth is not only affecting trade, finance, science, the environment, crime, and terrorism; it is also changing the nature of health challenges facing people all over the world.1

In 1997 an influential report by the US Institute of Medicine stated: “Distinctions between domestic and international health problems are losing their usefulness and are often misleading.”2 We are all coming closer to each other. One of the great revolutions of the 20th century was, in the words of the historian Eric Hobsbawm, the virtual annihilation of time and distance.3

Summary points

Globalisation is affecting health as well as other aspects of human activity

All countries must deal with the international transfer of risks—whether this is of microbes, unregulated distribution of drugs, or tobacco marketing

On the other hand, globalisation makes the sharing of information on health care easier

The aspiration for good health is also a unifying factor across different parts of the world, cultures, and religions

The death of distance

Intense international contacts are not new. From time immemorial the forces of trade, migration, war, and conquest have bound together people from distant places. The expression “citizen of the world” was coined by the Greek philosopher Diogenes in the fourth century BC. What is new is the pace, range, and depth of integration. As never before, the consequences of actions that are taking place far away show up, literally, at our doorsteps.

The degree of proximity in our world can be illustrated by the fact that the number of international travellers has tripled since 1980, and it now reaches three million people every day. Last year the traffic on international telephone switchboards topped 100 billion for the first time.4

We cannot underestimate the implications of these changes for health. In addition to their own domestic problems, all countries must now deal with the international transfer of risks.5

The most obvious case of the blurring of health frontiers is the transmission of communicable diseases. Again, this is not in itself a new phenomenon. The first documented case of a transnational epidemic was the Athenian plague of 430 BC.6 The Black Death of 1347, which killed one third of the European population, was the direct result of international trade. In the 16th century the conquest of the Aztec and Inca empires was an early example of involuntary microbiological warfare through the introduction of smallpox to previously unexposed populations. More recently, the global spread of the influenza pandemic of the early 20th century accounted for far more casualties than the first world war.

Microbial traffic and other vectors

Again, what is new is the scale of what has been called “microbial traffic.” The explosive increase of world travel produces thousands of potentially infectious contacts daily. Even the longest intercontinental flights are briefer than the incubation period of any human infectious disease. Thus, a Peruvian outbreak of cholera turned into a continental epidemic in a matter of days in the early 1990s. Drug resistant strains of tuberculosis may travel from detention centres in Russia to Paris in just a few hours.7 Likewise, the Asian “tiger mosquito,” a potential vector for dengue fever virus, was introduced into the United States in the 1980s in a shipment of used tyres imported from northern Asia.8 These are all examples of what Arno Karlen has called our new biocultural era, generated by radical changes in our environment and life styles.9

Indeed, to make matters more complex, it is not only people, microbes, and material goods that travel from one country to another; it is also ideas and lifestyles. Take smoking as an example.

Whenever a legal or regulatory battle against the tobacco companies is won in the United States, we rejoice for the American public but tremble for the consequences in other countries because those victories give those same companies the incentive to look for new markets with less stringent regulations. Already about 4 million people are dying of smoking related causes every year. By 2020 that number will grow to 10 million, making tobacco the leading killer worldwide. This shows why effective national policies must be coupled with global action, like the international convention currently being promoted by the World Health Organization, whereby governments will join forces to match tobacco's transnational power.

Effects on health care

Furthermore, the globalisation of health goes beyond diseases and risk factors to include also health care and its inputs. For example, careful restrictions on access to prescription drugs in one country may be subverted when its neighbour allows the unrestricted purchase of antibiotics, thereby stimulating the appearance of resistant microbes in the first country. The growing commerce of pharmaceutical products and healthcare services over the internet is another way in which national authorities may be bypassed.

Interdependence has also opened up new avenues for international collective action. For instance, initial efforts in the 1990s to secure cheaper drugs for AIDS victims in poor countries yielded only modest results. A few months ago, however, strong international mobilisation persuaded several major multinational drug companies to establish agreements with developing countries to sell AIDS drugs at heavily discounted prices.

Forces related to globalisation also prompted the organisation of the UN General Assembly special session on HIV/AIDS in June 2001, which approved a historical declaration of commitment. This was the first time that a session of the general assembly was devoted to a health topic, thus underscoring the growing link between pandemics such as AIDS with economic development and global security.

These are two clear examples of what Richard Feachem recently called “the political benefits of openness.”10

Information as a global public good

Increasing communication, in the face of the growing complexity of health systems, has also made international comparisons more valuable than ever. Given the enormous economic and social impact of policy decisions, countries can benefit from a process of shared learning. This is the significance of the recent effort by the World Health Organization (WHO) to assess the performance of all 191 health systems of the world. Imperfect as it is, this exercise has nourished an intense and fruitful debate, which builds on previous efforts by academic and intergovernmental organisations such as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). This kind of comparative analysis has the virtue of turning information into a global public good, a topic widely addressed at the recent meeting convened by the UN in Monterrey, Mexico, on development financing.11 Global public goods for health were also well discussed by the Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, whose report was launched recently.12

The performance of local health systems can also be enhanced by one of the most potent motors of globalisation: the telecommunications revolution. This is opening up the prospect of improving access to care for underserved populations. Telemedicine points the way to a future when physical distance may no longer be a significant barrier to health care.

The challenge, of course, will be to make sure that the distance divide is not merely replaced by the digital divide. The size of this challenge becomes clear when we realise that the 80% of the population living in developing countries represents less than 10% of internet users.13 Canada, the United States, and Sweden rank among the most wired nations, with 40% of their population regularly connected to the internet.14 In contrast, many African countries can count just a few hundred active internet users.

The dark side of globalisation

The new forms of social exclusion feed on the old scourges of poverty and inequality. The 1.3 billion people who survive on $1 a day are a reminder to all of the enormous gaps that must still be overcome within and between countries.

Exclusion and inequality are one dark side of globalisation. Insensitivity to local cultures is another. Together they may explain a painful paradox of our days: Precisely when technology has brought human beings closer to each other than ever before, we are witnessing intolerance in its ugly guises of xenophobia and ethnic cleansing. According to the French philosopher Regis Debray, there seems to be an intrinsic relation between the disappearance of cultural points of reference and the dogmatic reaffirmation of the myths of origins.15

And with intolerance, as a Siamese twin, comes terrorism, traditionally the instrument of offended fanatical minorities that resist believing in persuasion. At its essence, terrorism is the worst form of dehumanisation, as it turns innocent people into mere targets.

In the long run, the challenge we have before us is to build a world order characterised by peace in the midst of diversity. Instead of asserting one's identity by rejecting or destroying what is different, we must try to soften collisions, balance claims, and reach compromises.16 In this way, we may try living according to what President Vaclav Havel of the Czech Republic has called a basic code of mutual coexistence.17

Health as a force for unity

Even as we share America's grief over the attack of 11 September, we must join together in searching for new ways of making our interdependence a force for peace and prosperity. As Prime Minister Blair said, the best memorial for those who lost their lives on 11 September will be “A new beginning, where we seek to resolve differences in a calm and ordered way; greater understanding between nations and between faiths; and above all justice and prosperity for the poor and dispossessed, so that people everywhere can see the chance of a better future through the hard work and creative power of the free citizen” (Labour Party Conference, Brighton, October 2001).

Health may contribute to this pursuit because it involves those domains that unite all human beings. It is there, in birth, in sickness, in recovery, and ultimately in death that we can all find our common humanity. In our turbulent world health remains one of the few truly universal aspirations. It therefore offers a concrete opportunity to reconcile national self interest with international mutual interest. More today than ever, health is a bridge to peace, a common ground, a source for shared security.

But for this to happen, we must renew international cooperation for health. “Successful globalisation,” says George Soros, “requires effective global institutions devoted not only to finance and trade, but also to public health, human rights, [and] environmental protection.”18

Exchange, evidence, and empathy

We suggest three key elements for such renewal, three “e's”: exchange, evidence, and empathy.

Firstly, we should exchange experiences around common problems.

Secondly, we need evidence on alternatives, so that we may build a solid knowledge base of what works and what doesn't. This is why international comparative analysis of health systems is so important.

But there is another value. The late British philosopher Isaiah Berlin proposed the comparative studies of other cultures as an antidote to intolerance, stereotypes, and the dangerous delusion by individuals, tribes, states, and religions of being the sole possessors of truth.19 And this leads to the third element, empathy—that human characteristic which allows us to participate mentally in a foreign reality, understand it, relate to it, and, in the end, value the core elements that make us all members of the human race.

As we engage in the process of renewal, we would do well to remember the words of a great American, Martin Luther King Jr: “It really boils down to this: that all life is interrelated. We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied into a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”20

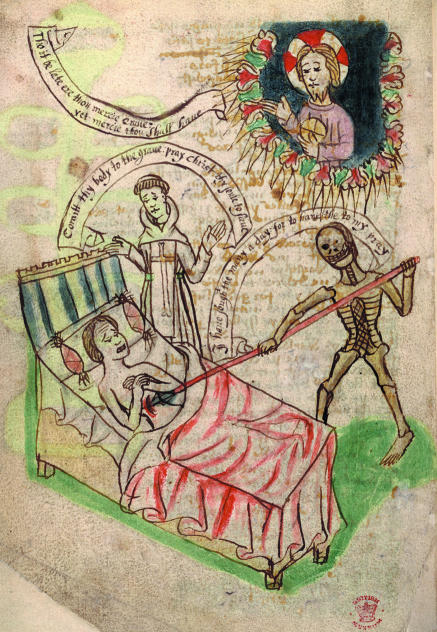

Figure.

THE BRITISH LIBRARY

Globalisation is nothing new: the Black Death of the 14th century was a direct result of international trade

Acknowledgments

This article is based on a talk given to a meeting on globalisation and health in San Francisco in May 2002 and on a fuller article published in the May-June issue of Health Affairs.

References

- 1.Valaskakis K. Westfalia II: por un nuevo orden mundial. Este País. 2001;126:4–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Board on International Health; Institute of Medicine. America's vital interest in global health: protecting our people, enhancing our economy, and advancing our international interests. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hobsbawm E. The age of extremes: a history of the world. 1914-1991. New York: Pantheon Books; 1994. p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 4. AT Kearny Inc. Foreign policy. measuring globalization. Foreign Policy 2001;Jan-Feb.

- 5.Frenk J, Sepulveda J, Gomez-Dantes O, McGuinness MJ, Knaul F. The new world order and international health. BMJ. 1997;314:1404–1407. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7091.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen LC, Evans TG, Cash RA. Health as a global pubic good. In: Kaul Y, Grumberg Y, Stern MA, editors. Global public goods: international cooperation in the 21st century. New York: Oxford University Press for the United Nations Development Programme; 1999. pp. 284–304. [Google Scholar]

- 7.York G. A deadly strain of TB races toward the West. Toronto Globe and Mail. 1999;March 24:A1. and A12. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawley WA, Reiter P, Copeland RW, Pumpini CB, Craig Jr GB. Aedes albopictus in North America: probable introduction in used tires from northern Asia. Science. 1987;236:1114–1116. doi: 10.1126/science.3576225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karlen A. Man and microbes. Disease and plagues in history and modern times. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feachem R. Globalisation is good for your health, mostly. BMJ. 2001;323:504–506. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7311.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaul I, Grumberg Y, Stern MA, editors. Global public goods: international cooperation in the 21st century. New York: Oxford University Press for the United Nations Development Programme; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Macroeconomics and health: investing in health for economic development. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 1999. New York: Oxford University Press for the United Nations Development Programme; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prescott-Allen R. The wellbeing of nations. A country-by-country index of quality of life and the environment. Washington, DC: Island Press, International Development Research Center; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Debray R. God and the political planet. New Perspectives Q 2001;9(1).

- 16.Berlin I. The crooked timber of humanity. New York: Vintage Books; 1992. The pursuit of the ideal; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Havel V. A courageous and magnanimous creation. Harvard Gazette. 1995;June 15:9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Epstein H, Chen L. Can AIDS be stopped? New York Review of Books 2001;14 March.

- 19.Berlin I. Nacionalismo: notas para una conferencia futura. Letras Libres. 2001;3:105–106. [Google Scholar]

- 20.King ML., jr . Trumpet of conscience. New York: Harper; 1968. [Google Scholar]