Abstract

The European Commission requested the EFSA Panel on Plant Health to conduct a pest categorisation of Ceroplastes rubens Maskell (Hemiptera: Coccidae), following the commodity risk assessments of Acer palmatum plants grafted on A. davidii and Pinus parviflora bonsai plants grafted on P. thunbergii from China, in which C. rubens was identified as a pest of possible concern to the European Union (EU). The pest, which is commonly known as the pink, red or ruby wax scale, originates in Africa and is highly polyphagous attacking plants from more than 193 genera in 84 families. It has been present in Germany since 2010 in a single tropical glasshouse. It is known to attack primarily tropical and subtropical plants, but also other host plants commonly found in the EU, such as Malus sylvestris, Prunus spp., Pyrus spp. and ornamentals. It is considered an important pest of Citrus spp. The pink wax scale reproduces mainly parthenogenetically, and it has one or two generations per year. Fecundity ranges from 5 to 1178 eggs. Crawlers settle usually on young twigs and later stages are sessile. All life stages of C. rubens egest honeydew on which sooty mould grows. Host availability and climate suitability suggest that parts of the EU would be suitable for establishment. Plants for planting and cut branches provide the main pathways for entry. Crawlers could spread over short distances naturally through wind, animals, humans or machinery. C. rubens could be dispersed more rapidly and over long distances via infested plants for planting for trade. The introduction of C. rubens into the EU could lead to outbreaks causing damage to orchards, amenity ornamental trees and shrubs. Phytosanitary measures are available to inhibit the entry and spread of this species. C. rubens satisfies the criteria that are within the remit of EFSA to assess for it to be regarded as a potential Union quarantine pest.

Keywords: citrus, Coccidae, pest risk, plant health, plant pest, quarantine, ruby wax scale

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background and Terms of Reference as provided by the requestor

1.1.1. Background

The new Plant Health Regulation (EU) 2016/2031, on the protective measures against pests of plants, is applying from 14 December 2019. Conditions are laid down in this legislation in order for pests to qualify for listing as Union quarantine pests, protected zone quarantine pests or Union regulated non‐quarantine pests. The lists of the EU regulated pests together with the associated import or internal movement requirements of commodities are included in Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072. Additionally, as stipulated in the Commission Implementing Regulation 2018/2019, certain commodities are provisionally prohibited to enter in the EU (high risk plants, HRP). EFSA is performing the risk assessment of the dossiers submitted by exporting to the EU countries of the HRP commodities, as stipulated in Commission Implementing Regulation 2018/2018. Furthermore, EFSA has evaluated a number of requests from exporting to the EU countries for derogations from specific EU import requirements.

In line with the principles of the new plant health law, the European Commission with the Member States are discussing monthly the reports of the interceptions and the outbreaks of pests notified by the Member States. Notifications of an imminent danger from pests that may fulfil the conditions for inclusion in the list of the Union quarantine pest are included. Furthermore, EFSA has been performing horizon scanning of media and literature.

As a follow‐up of the above‐mentioned activities (reporting of interceptions and outbreaks, HRP, derogation requests and horizon scanning), a number of pests of concern have been identified. EFSA is requested to provide scientific opinions for these pests, in view of their potential inclusion by the risk manager in the lists of Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072 and the inclusion of specific import requirements for relevant host commodities, when deemed necessary by the risk manager.

1.1.2. Terms of Reference

EFSA is requested, pursuant to Article 29(1) of Regulation (EC) No 178/2002, to provide scientific opinions in the field of plant health.

EFSA is requested to deliver 53 pest categorisations for the pests listed in Annex 1A, 1B, 1D and 1E (for more details see mandate M‐2021‐00027 on the Open.EFSA portal). Additionally, EFSA is requested to perform pest categorisations for the pests so far not regulated in the EU, identified as pests potentially associated with a commodity in the commodity risk assessments of the HRP dossiers (Annex 1C; for more details see mandate M‐2021‐00027 on the Open.EFSA portal). Such pest categorisations are needed in the case where there are not available risk assessments for the EU.

When the pests of Annex 1A are qualifying as potential Union quarantine pests, EFSA should proceed to phase 2 risk assessment. The opinions should address entry pathways, spread, establishment, impact and include a risk reduction options analysis.

Additionally, EFSA is requested to develop further the quantitative methodology currently followed for risk assessment, in order to have the possibility to deliver an express risk assessment methodology. Such methodological development should take into account the EFSA Plant Health Panel Guidance on quantitative pest risk assessment and the experience obtained during its implementation for the Union candidate priority pests and for the likelihood of pest freedom at entry for the commodity risk assessment of High Risk Plants.

1.2. Interpretation of the Terms of Reference

Ceroplastes rubens is one of a number of pests covered by Annex 1C to the terms of reference (ToR) to be subject to pest categorisation to determine whether it fulfils the criteria of a potential Union quarantine pest for the area of the EU excluding Ceuta, Melilla and the outermost regions of Member States referred to in Article 355(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), other than Madeira and the Azores, and so inform EU decision‐making as to its appropriateness for potential inclusion in the lists of pests of Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/ 2072. If a pest fulfils the criteria to be potentially listed as a Union quarantine pest, risk reduction options will be identified.

1.3. Additional information

This pest categorisation was initiated following the commodity risk assessments of Acer palmatum plants grafted on A. davidii from China (EFSA PLH Panel, 2022a) and of bonsai plants from China consisting of Pinus parviflora grafted on P. thunbergii (EFSA PLH Panel, 2022b), in which C. rubens was identified as a relevant non‐regulated pest which could potentially enter the EU on Acer spp. and Pinus spp. plants for planting.

2. DATA AND METHODOLOGIES

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Information on pest status from NPPOs

In the context of the current mandate, EFSA is preparing pest categorisations for new/emerging pests that are not yet regulated in the EU. When official pest status is not available in the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) Global Database (EPPO, online), EFSA consults the NPPO of any relevant MS. To obtain information on the official pest status for C. rubens, EFSA contacted the NPPOs of Germany and Hungary in February and March 2024.

2.1.2. Literature search

A literature search on C. rubens was conducted at the beginning of the categorisation in the ISI Web of Science bibliographic database, using the scientific name of the pest as search term. Papers relevant for the pest categorisation were reviewed, and further references and information were obtained from experts, as well as from citations within the references and grey literature.

2.1.3. Database search

Pest information, on host(s) and distribution, was retrieved from the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) Global Database (EPPO, online), the CABI databases and scientific literature databases as referred above in Section 2.1.1.

Data about the import of commodity types that could potentially provide a pathway for the pest to enter the EU and about the area of hosts grown in the EU were obtained from EUROSTAT (Statistical Office of the European Communities).

The Europhyt and TRACES databases were consulted for pest‐specific notifications on interceptions and outbreaks. Europhyt is a web‐based network run by the Directorate General for Health and Food Safety (DG SANTÉ) of the European Commission as a subproject of PHYSAN (Phyto‐Sanitary Controls) specifically concerned with plant health information. TRACES is the European Commission's multilingual online platform for sanitary and phytosanitary certification required for the importation of animals, animal products, food and feed of non‐animal origin and plants into the European Union, and the intra‐EU trade and EU exports of animals and certain animal products. Up until May 2020, the Europhyt database managed notifications of interceptions of plants or plant products that do not comply with EU legislation, as well as notifications of plant pests detected in the territory of the Member States and the phytosanitary measures taken to eradicate or avoid their spread. The recording of interceptions switched from Europhyt to TRACES in May 2020.

GenBank was searched to determine whether it contained any nucleotide sequences for Ceroplastes rubens which could be used as reference material for molecular diagnosis. GenBank® (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) is a comprehensive publicly available database that as of August 2019 (release version 227) contained over 6.25 trillion base pairs from over 1.6 billion nucleotide sequences for 450,000 formally described species (Sayers et al., 2020).

2.2. Methodologies

The Panel performed the pest categorisation for C. rubens, following guiding principles and steps presented in the EFSA guidance on quantitative pest risk assessment (EFSA PLH Panel, 2018), the EFSA guidance on the use of the weight of evidence approach in scientific assessments (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2017) and the International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures No. 11 (FAO, 2013).

The criteria to be considered when categorising a pest as a potential Union quarantine pest (QP) is given in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 Article 3 and Annex I, Section 1 of the Regulation. Table 1 presents the Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 pest categorisation criteria on which the Panel bases its conclusions. In judging whether a criterion is met the Panel uses its best professional judgement (EFSA Scientific Committee, 2017) by integrating a range of evidence from a variety of sources (as presented above in Section 2.1) to reach an informed conclusion as to whether or not a criterion is satisfied.

TABLE 1.

Pest categorisation criteria under evaluation, as derived from Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column).

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Criterion in regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding union quarantine pest (article 3) |

|---|---|

| Identity of the pest (Section 3.1 ) | Is the identity of the pest clearly defined, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and to be transmissible? |

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU territory (Section 3.2 ) |

Is the pest present in the EU territory? If present, is the pest in a limited part of the EU or is it scarce, irregular, isolated or present infrequently? If so, the pest is considered to be not widely distributed. |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU territory (Section 3.4 ) | Is the pest able to enter into, become established in, and spread within, the EU territory? If yes, briefly list the pathways for entry and spread |

| Potential for consequences in the EU territory (Section 3.5 ) | Would the pests' introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory? |

| Available measures (Section 3.6 ) | Are there measures available to prevent pest entry, establishment, spread or impacts? |

| Conclusion of pest categorisation (Section 4 ) | A statement as to whether (1) all criteria assessed by EFSA above for consideration as a potential quarantine pest were met and (2) if not, which one(s) were not met |

The Panel's conclusions are formulated respecting its remit and particularly with regard to the principle of separation between risk assessment and risk management (EFSA founding regulation (EU) No 178/2002); therefore, instead of determining whether the pest is likely to have an unacceptable impact, deemed to be a risk management decision, the Panel will present a summary of the observed impacts in the areas where the pest occurs, and make a judgement about potential likely impacts in the EU. While the Panel may quote impacts reported from areas where the pest occurs in monetary terms, the Panel will seek to express potential EU impacts in terms of yield and quality losses and not in monetary terms, in agreement with the EFSA guidance on quantitative pest risk assessment (EFSA PLH Panel, 2018). Article 3 (d) of Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 refers to unacceptable social impact as a criterion for quarantine pest status. Assessing social impact is outside the remit of the Panel.

3. PEST CATEGORISATION

3.1. Identity and biology of the pest

3.1.1. Identity and taxonomy

Is the identity of the pest clearly defined, or has it been shown to produce consistent symptoms and/or to be transmissible?

Yes, the identity of the species is established and Ceroplastes rubens Maskell is the accepted name.

Ceroplastes rubens Maskell (1893) is an insect within the order Hemiptera and family Coccidae, commonly known as the pink, red or ruby wax scale (EPPO, online; García Morales et al., 2016).

C. rubens was originally described by Maskell (1893), from material collected from Mangifera indica (mango) and Ficus sp. in Queensland, Australia (García Morales et al., 2016). Ceroplastes rubens minor Maskell (1897) is a synonym (García Morales et al., 2016).

The EPPO code 1 (EPPO, 2019; Griessinger & Roy, 2015) for this species is CERPRB (EPPO, online).

3.1.2. Biology of the pest

C. rubens completes its life cycle in three developmental stages (egg, nymph and adult). The female passes through four nymphal instars and the male through five (Malumphy, 2014). Adult females deposit their eggs in a mass beneath their concave ventral surface (Waterhouse & Sands, 2001). First‐instar nymphs, known as crawlers, usually settle at or near the leaf veins (Blumberg, 1935; Waterhouse & Sands, 2001), however, in a study of Citrus unshiu in Japan, crawlers showed a preference for settling on new season twigs (Itioka & Inoue, 1991). At the end of the first‐instar stage, a wax shell cover is formed on their body. This wax shell becomes larger and thicker with the subsequent growth of the nymph, protecting it against predators, parasitoids and desiccation (Itioka, 1993; Itioka & Inoue, 1991; Sands, 1984). C. rubens egests honeydew throughout its lifetime, attracting some ant species for foraging, and rarely wasps and flies (Malumphy, 2014). Honeydew droplets accumulate on leaves, twigs and on the scale colonies (Itioka & Inoue, 1996). This honeydew provides a medium for the growth of sooty mould fungus (Hodges et al., 2001).

Table 2 summarises key features of the biology of each life stage.

TABLE 2.

Important features of the life history strategy of Ceroplastes rubens.

| Life stage | Phenology and relation to host | Other relevant information |

|---|---|---|

| Egg | Fecundity ranged from 5 to 1178 eggs in Australia, and from 500 to 800 in China (Loch & Zalucki, 1997; Lu & Jiang, 2015). Hatching occurs after 2–3 days of oviposition (Itioka & Inoue, 1991) | |

| Nymph | Found on twigs, usually young twigs (0–1‐year‐old) and leaves (especially the upper surface across or on the leaf veins) (Waterhouse & Sands, 2001). In southern New South Wales of Australia and China, first emergence of crawlers occurs during late spring, in Japan in early summer and in South Africa and northern New South Wales and Queensland of Australia early spring (Bi et al., 2022; Itioka & Inoue, 1996; Prinsloo & Uys, 2015; Waterhouse & Sands, 2001). In Japan, second‐ and third‐instar nymphs emerge in mid‐summer and late summer, respectively (Itioka & Inoue, 1996) | The crawlers have well‐developed legs and are mobile. After hatching the crawlers settle to feed within 6 h. After settling, they do not move further than this point and tend to form aggregations around the adult female (Waterhouse & Sands, 2001) |

| Adult | Adults are found on leaves, branches and stems of host plants (Malumphy, 2014). Hill (2008) reported that C. rubens may cover shoots, fruit stalks and parts of the fruits. In Japan, adult females overwinter and begin to oviposit from early to mid‐July for a 20 day‐period (Itioka & Inoue, 1996). Reproduction is mainly parthenogenic (Waterhouse & Sands, 2001). However, in Shanghai where males are more common, it is reported that the pest reproduces sexually and overwinter as fertilised females (Lu & Jiang, 2015; Xia et al., 2005) | Males were rarely identified in Japan and never in Australia (Hamon & Williams, 1984; Itioka & Inoue, 1996; Qin & Gullan, 1994) |

The pest is either univoltine (e.g. in China, Japan and southern New South Wales of Australia) or bivoltine (e.g. in South Africa, northern New South Wales and Queensland of Australia) (Berry, 2014; Itioka & Inoue, 1996; Malumphy et al., 2018; Smith, 1976). The duration of the life cycle varies based on the season. In Australia, summer generation can last from 4 to 6 months, while in winter from 6 to 8 months (Blumberg, 1935). According to Blumberg (1935), newly hatched nymphs do not survive after 4 or 5 days without food, while adults can produce eggs after 40–46 days of starvation.

3.1.3. Host range/species affected

C. rubens is a highly polyphagous pest, feeding on plants in more than 193 genera in 84 plant families (García Morales et al., 2016). It attacks primarily tropical and subtropical plants but additionally Malus sylvestris, Prunus spp., Pyrus spp. and ornamentals (Malumphy, 2010). The insect has also been reported as a pest of Pinus spp., specifically found on seedlings in nurseries (Waterhouse & Sands, 2001) and in seed orchards (Merrifield & Howcroft, 1975). According to Summerville (1935), C. rubens is an important pest of Citrus spp., mainly mandarin (Citrus reticulata) and Washington navel orange (Citrus × aurantium var. sinensis, CRC 1241A). It is occasionally found on other Citrus species, while rarely on grapefruit (Citrus × aurantium var. paradisi) and lemon (Citrus × limon). The full host list is presented in Appendix A.

3.1.4. Intraspecific diversity

No intraspecific diversity is reported for this species.

3.1.5. Detection and identification of the pest

Are detection and identification methods available for the pest?

Yes, there are methods available for detection and morphological identification of C. rubens.

Symptoms and Detection

Symptoms of infestation include deposition of sugary honeydew, which fouls plant surfaces (usually leaves and fruits). This honeydew provides a medium for the growth of sooty mould fungus on leaves, reducing the active photosynthetic area (Hodges et al., 2001). Heavy infestations of wax scales can cause leaf discoloration and premature drop, branch dieback and even plant death. Therefore, they cause loss of production and reduce the aesthetic value of the crop or the produce (Malumphy, 2014; Vithana et al., 2019). Symptoms on Pinus spp. are more distinctive, C. rubens affects mainly the upper crown needles leading to sparse and dark foliage covered by sooty‐mould and reduced height (Merrifield & Howcroft, 1975). Scales can be detected by visual inspection on leaves by their thick wax layer forming a pentagonal or amorphous shape (CABI, online). Usually, they settle on the upper side along the leaf‐veins and stems (Malumphy, 2014).

Identification

The identification of C. rubens requires microscopic examination and verification of the presence of key morphological characteristics. Detailed morphological descriptions, illustrations and keys to adult and nymphal instars of C. rubens can be found in Borchsenius (1957), Gimpel et al. (1974), Hodgson (1994), Qin and Gullan (1994), Tang (1991) and Ben‐Dov et al. (2000).

Molecular diagnostic protocols for C. rubens identification such as sequences from the DNA barcode region of the mitochondrial COI gene have been suggested by Deng et al. (2012), Wang et al. (2015) and Lu et al. (2023).

When Genbank was searched on 22 March 2024, there were 126 gene nucleotide sequences of C. rubens (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/taxonomy/536005/).

Description

Eggs

Eggs are pink, usually found in masses in a cavity under the female body, protected by the waxy test (Vithana et al., 2019; Waterhouse & Sands, 2001).

Nymphs

First‐instar nymphs are mobile and pink, with three pairs of legs, eyespots and antennae (Prinsloo & Uys, 2015; Vithana et al., 2019). Within 24 h after settling, two pairs of white marginal points of wax appear. Within a week, a thick wax layer covers the general body surface and turns purple. After 15 days from settling, the dorsum appears purple producing small amounts of powdery white wax (Blumberg, 1935). Secretion of clumps of wax also occurs on the second‐ and third‐instar nymphs which appear star‐shaped (Vithana et al., 2019). The fourth‐instar nymphs usually do not migrate further (Waterhouse & Sands, 2001). A detailed morphological description and illustration of all four instars is provided by Blumberg (1935).

Adults

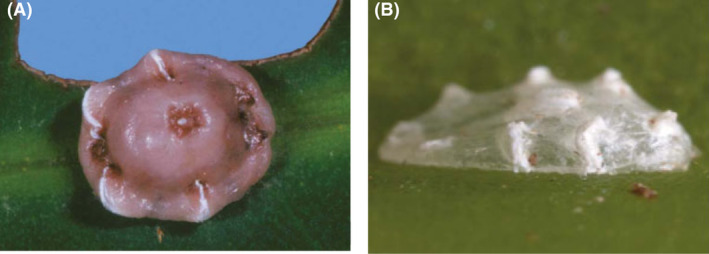

Adult females are covered in a dense layer of watery wax which varies in colour from white, cream, pink (Figure 1A), reddish or even brownish. It is strongly convex, longer than wide, pentagonal in dorsal view, and with two conspicuous pairs of white bands that extend dorsally from the anterior margin and halfway along the body; female wax cover length 3.5–4.5 mm. Adult C. rubens can usually be recognised in life by the presence of these white bands, particularly by the anterior bands which often almost touch each other. Immature males form a whitish translucent, elongate, oval scale (Malumphy & Eyre, 2011; Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Ceroplastes rubens (A) Adult female (©Kondo, 2008) and (B) Male cover on Aglaonema from Sri Lanka (©Fera).

3.2. Pest distribution

3.2.1. Pest distribution outside the EU

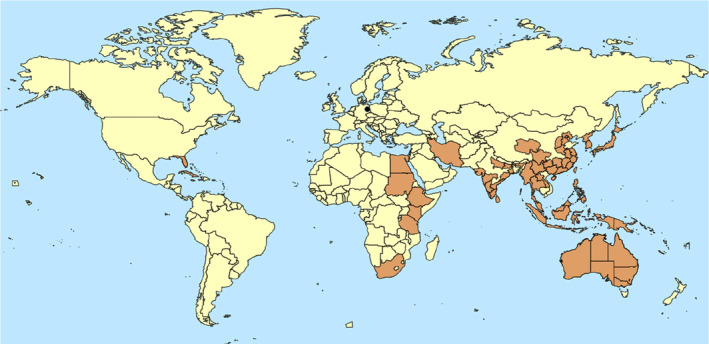

C. rubens is of African origin (Waterhouse & Sands, 2001). It is widely distributed in south Asia, Australia (except Tasmania), India, South Pacific, East Africa and the Carribean (Figure 2). It has also been reported from the USA, from Florida and Hawaii. Usually when found in temperate climates, it is present in protected environment, e.g. greenhouses or tropical gardens (Hodgson, 1994). The list of countries where the presence of C. rubens is reported is shown in detail in Appendix B.

FIGURE 2.

Global distribution of Ceroplastes rubens (Source: EPPO Global Database (EPPO, online), CABI CPC (CABI, online) and García Morales et al. (2016) accessed on 3 January 2024 and literature; for details, see Appendix B. In EU (Germany) one location point appears in the map, as C. rubens was found in a tropical indoor garden and has not been established further.

3.2.2. Pest distribution in the EU

Is the pest present in the EU territory?

Yes, C. rubens is present at one location in Germany.

If present, is the pest in a limited part of the EU or is it scarce, irregular, isolated or present infrequently? If so, the pest is considered to be not widely distributed.

C. rubens has restricted distribution in the EU; It has only been reported in a tropical greenhouse in Germany (Brandenburg) in 2010 and is still considered to be present but has not established further.

In Germany, C. rubens was collected from a tropical greenhouse in Brandenburg from Aglaonema sp. plants in 2010 (Schönfeld, 2015). According to the official reply by the German NPPO ‘The finding of Ceroplastes rubens on Aglaonema sp. in a Tropical Hall in the federal state of Brandenburg in 2010 has remained unique for Germany and no official measures against this pest have been considered.’ The pest status in Germany has been declared as ‘Present, at one location’.

In Hungary, C. rubens was collected from Schefflera sp. in a botanical garden in Budapest, in 2012 (Fetyko & Kozar, 2012). The Hungarian NPPO has declared its status as: ‘Absent, confirmed by survey’.

3.3. Regulatory status

3.3.1. Commission Implementing Regulation 2019/2072

C. rubens is not listed in Annex II of Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072, an implementing act of Regulation (EU) 2016/2031. It is not known to be in any emergency EU plant health legislation either.

3.3.2. Hosts or species affected that are prohibited from entering the union from third countries

A number of C. rubens hosts are prohibited from entering the EU (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

List of plants, plant products and other objects that are Ceroplastes rubens hosts whose introduction into the Union from certain third countries is prohibited (Source: Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/2072, Annex VI).

| List of plants, plant products and other objects whose introduction into the union from certain third countries is prohibited | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | CN code | Third country, group of third countries or specific area of third country | |

| 1. | Plants of […]., Cedrus Trew, […] Pinus L., […] other than fruit and seeds |

ex 0602 20 20 ex 0602 20 80 ex 0602 90 41 ex 0602 90 45 ex 0602 90 46 ex 0602 90 47 ex 0602 90 50 ex 0602 90 70 ex 0602 90 99 ex 0604 20 20 ex 0604 20 40 |

Third countries other than Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Canary Islands, Faeroe Islands, Georgia, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Norway, Russia (only the following parts: Central Federal District (Tsentralny federalny okrug), Northwestern Federal District (Severo‐ Zapadny federalny okrug), Southern Federal District (Yuzhny federalny okrug), North Caucasian Federal District (Severo‐Kavkazsky federalny okrug) and Volga Federal District (Privolzhsky federalny okrug)), San Marino, Serbia, Switzerland, Türkiye, Ukraine and the United Kingdom |

| 2. | Plants of […] Quercus L., with leaves, other than fruit and seeds |

ex 0602 10 90 ex 0602 20 20 ex 0602 20 80 ex 0602 90 41 ex 0602 90 45 ex 0602 90 46 ex 0602 90 48 ex 0602 90 50 ex 0602 90 70 ex 0602 90 99 ex 0604 20 90 ex 1404 90 00 |

Third countries other than Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Canary Islands, Faeroe Islands, Georgia, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Norway, Russia (only the following parts: Central Federal District (Tsentralny federalny okrug), Northwestern Federal District (Severo‐ Zapadny federalny okrug), Southern Federal District (Yuzhny federalny okrug), North Caucasian Federal District (Severo‐Kavkazsky federalny okrug) and Volga Federal District (Privolzhsky federalny okrug)), San Marino, Serbia, Switzerland, Türkiye, Ukraine and the United Kingdom |

| 8. | Plants for planting of Chaenomeles Ldl., […] Malus Mill., Prunus L., Pyrus L. […] other than dormant plants free from leaves, flowers and fruits |

ex 0602 10 90 ex 0602 20 20 ex 0602 20 80 ex 0602 40 00 ex 0602 90 41 ex 0602 90 45 ex 0602 90 46 ex 0602 90 47 ex 0602 90 48 ex 0602 90 50 ex 0602 90 70 ex 0602 90 91 ex 0602 90 99 |

Third countries other than Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Canary Islands, Faeroe Islands, Georgia, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Norway, Russia (only the following parts: Central Federal District (Tsentralny federalny okrug), Northwestern Federal District (Severo‐ Zapadny federalny okrug), Southern Federal District (Yuzhny federalny okrug), North Caucasian Federal District (Severo‐Kavkazsky federalny okrug) and Volga Federal District (Privolzhsky federalny okrug)), San Marino, Serbia, Switzerland, Türkiye, Ukraine and the United Kingdom |

| 9. | Plants for planting of […] Malus Mill., Prunus L. and Pyrus L. and their hybrids, and […] other than seeds |

ex 0602 10 90 ex 0602 20 20 ex 0602 90 30 ex 0602 90 41 ex 0602 90 45 ex 0602 90 46 ex 0602 90 48 ex 0602 90 50 ex 0602 90 70 ex 0602 90 91 ex 0602 90 99 |

Third countries other than Albania, Algeria, Andorra, Armenia, Australia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Canada, Canary Islands, Egypt, Faeroe Islands, Georgia, Iceland, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Liechtenstein, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, Morocco, New Zealand, North Macedonia, Norway, Russia (only the following parts: Central Federal District (Tsentralny federalny okrug), Northwestern Federal District (Severo‐Zapadny federalny okrug), Southern Federal District (Yuzhny federalny okrug), North Caucasian Federal District (Severo‐ Kavkazsky federalny okrug) and Volga Federal District (Privolzhsky federalny okrug)), San Marino, Serbia, Switzerland, Syria, Tunisia, Türkiye, Ukraine, the United Kingdom (1) and United States other than Hawaii |

| 11. | Plants of Citrus L., […] Poncirus Raf., and their hybrids, other than fruits and seeds |

ex 0602 10 90 ex 0602 20 200,602 20 30 ex 0602 20 80 ex 0602 90 45 ex 0602 90 46 ex 0602 90 47 ex 0602 90 50 ex 0602 90 70 ex 0602 90 91 ex 0602 90 99 ex 0604 20 90 ex 1404 90 00 |

All third countries |

| 12. | Plants for planting of Photinia Ldl., other than dormant plants free from leaves, flowers and fruits |

ex 0602 10 90 ex 0602 90 41 ex 0602 90 45 ex 0602 90 46 ex 0602 90 47 ex 0602 90 48 ex 0602 90 50 ex 0602 90 70 ex 0602 90 91 ex 0602 90 99 |

China, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Japan, Republic of Korea and United States |

| 18. | Plants for planting of Solanaceae other than seeds and the plants covered by entries 15, 16 or 17 |

ex 0602 10 90 ex 0602 90 30 ex 0602 90 45 ex 0602 90 46 ex 0602 90 48 ex 0602 90 50 ex 0602 90 70 ex 0602 90 91 ex 0602 90 99 |

Third countries other than: Albania, Algeria, Andorra, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Canary Islands, Egypt, Faeroe Islands, Georgia, Iceland, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Liechtenstein, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, Morocco, North Macedonia, Norway, Russia (only the following parts: Central Federal District (Tsentralny federalny okrug), Northwestern Federal District (Severo‐Zapadny federalny okrug), Southern Federal District (Yuzhny federalny okrug), North Caucasian Federal District (Severo‐Kavkazsky federalny okrug) and Volga Federal District (Privolzhsky federalny okrug)), San Marino, Serbia, Switzerland, Syria, Tunisia, Türkiye, Ukraine and the United Kingdom |

Points to note from Table 3: Although a number of host genera are prohibited from entering into the EU, some are permitted from the United States and Egypt (i.e. item 9, Plants for planting of Malus Mill., Prunus L. and Pyrus L.) where C. rubens occurs. However, Malus Mill. and Prunus L. fall under the high risk plant legislation (Regulation (EU) 2018/2019; see below), excluding Pyrus L. Also, Photinia spp. (i.e. item 12) and Solanaceae (i.e. item 18) are permitted from several countries where C. rubens is present.

The following C. rubens host genera are listed in Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2018/2019 as high‐risk plants for planting, whose introduction into the Union is prohibited pending risk assessment other than as seeds, in vitro material or naturally or artificially dwarfed woody plants: Acacia Mill., Acer L., Annona L., Bauhinia L., Diospyros L., Ficus carica L., Ligustrum L., Malus Mill., Persea Mill., Prunus L., Quercus L.

3.4. Entry, establishment and spread in the EU

3.4.1. Entry

Is the pest able to enter into the EU territory? If yes, identify and list the pathways.

Yes, C. rubens could re‐enter the EU via the import of host plants for planting (excluding seed and pollen) or on cut branches and occasionally on fruits.

Comment on plants for planting as a pathway.

Plants for planting provide the most likely pathway for entry into, and spread within, the EU.

Table 4 provides broad descriptions of potential pathways for the entry of C. rubens into the EU.

TABLE 4.

Potential pathways for Ceroplastes rubens into the EU.

| Pathways Description (e.g. host/intended use/source) | Life stage | Relevant mitigations [e.g. prohibitions (Annex VI), special requirements (Annex VII) or phytosanitary certificates (Annex XI) within Implementing Regulation 2019/2072] |

|---|---|---|

| Plants for planting (dormant/without leaves) (excluding seed) | All life stages |

Plants for planting that are hosts of C. rubens and are prohibited from third countries (Regulation 2019/2072, Annex VI) are listed in Table 3 Some hosts are considered high‐risk plants (Regulation EU 2018/2019) for the EU and their import is prohibited subject to risk assessment |

| Plants for planting (with buds or leaves; excluding seed) | All life stages |

Plants for planting that are hosts of C. rubens and are prohibited from third countries (Regulation 2019/2072, Annex VI) are listed in Table 3 Some hosts are considered high‐risk plants (Regulation EU 2018/2019) for the EU and their import is prohibited subject to risk assessment |

| Cut branches | All life stages |

Annex XI (Part A) prohibitions apply for several host plants on foliage, branches and other parts of plants without flowers or flower buds, being goods of a kind suitable for bouquets or for ornamental purposes, fresh |

| Fruits | All life stages | Fruits from third countries require a phytosanitary certificate to be imported into the EU (2019/2072, Annex XI, Part A) |

When host plants are heavily infested, fruits can also be affected but considered as a rare pathway. At this level of infestation, the fruit would be highly deteriorated due to sooty mould formation and would be rejected. The most likely pathway for the scale is plants for planting as first instars are found on leaves, buds or twigs, feeding on the phloem. The detection is difficult at this stage, especially when the insect density is low (Malumphy, 2011). Appendix A lists the hosts of C. rubens. Some hosts are prohibited from entering the EU (see Section 3.3.2).

Annual imports of C. rubens hosts from countries where the pest is known to occur are provided in Table 5 and in details in Appendix C.

TABLE 5.

EU annual imports of some Ceroplastes rubens host plants from countries where C. rubens is present, 2018–2022 (tonnes) Source: Eurostat accessed on 3 April 2024

| Commodity | HS code | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus fruit, fresh or dried | 0805 | 10,253,519.58 | 9,715,660.50 | 11,947,564.03 | 12,146,801.25 | 11,022,256.45 |

| Dates, figs, pineapples, avocados, guavas, mangoes and mangosteens, fresh or dried | 0804 | 1,908,286.43 | 1,770,016.69 | 2,150,888.07 | 2,457,622.93 | 2,275,588.71 |

| Indoor rooted cuttings and young plants (excl. cacti) | 06029070 | 73,129.84 | 99,021.59 | 73249.58 | 85,712.39 | 41,868.17 |

| Fresh persimmons | 081070 | 212.05 | 7858.49 | 4991.91 | 5596.43 | 11,192.33 |

Notifications of interceptions of harmful organisms began to be compiled in Europhyt in May 1994 and in TRACES in May 2020. As of 05 January 2024, there were two interceptions of Ceroplastes sp., in 2012 and 2014, on Ficus macrocarpa (bonsai plants for planting or already planted) originating from China. In 2018, one interception of C. rubens was recorded on bonsai Ilex sp. plants for planting also from China. According to Jansen (1995), C. rubens was intercepted in the Netherlands in 1978 on Aglaonema plants imported from Sri Lanka, and on Podocarpus plants from Taiwan.

In the UK, C. rubens has been intercepted several times throughout the years, from 1984 until 2007 on various host plants, mainly ornamentals, from Thailand and the USA (Malumphy, 2011). Between 1995 and 2012, C. rubens was intercepted 2321 times in the USA (Miller et al., 2014). A summary of the different interceptions recorded in the EU and UK is presented in Table 6.

TABLE 6.

Summary of interceptions of Ceroplastes rubens and Ceroplastes sp. in the EU and the UK in 1978–2018.*

| Year | Host plant | Country of entry | Country of origin | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | Aglaonema sp. | Netherlands | Sri Lanka | Jansen (1995) |

| 1978 | Podocarpus sp. | Netherlands | Taiwan | Jansen (1995) |

| 1984 1 | Cycas sp. | United Kingdom | Thailand | Malumphy (2011) |

| 1999 | Dimocarpus longan 2 | United Kingdom | Thailand | Malumphy (2010) |

| 2002 | Rhaphidophora sp. | United Kingdom | USA | Malumphy (2011) |

| 2005 | Citrus hystrix 2 | United Kingdom | Thailand | Malumphy (2011) |

| 2005 | Aglaonema sp. | United Kingdom | USA | Malumphy (2011) |

| 2006 | Various objects 3 | United Kingdom | New Zealand | Europhyt (online); TRACES (online) |

| 2007 | Unspecified aquatic plant | United Kingdom | Thailand | Malumphy (2010) |

| 2012 | Ficus macrocarpa 3 | Italy | China | Europhyt (online); TRACES (online) |

| 2014 | Ficus macrocarpa 3 | Spain | China | Europhyt (online); TRACES (online) |

| 2018 | Ilex sp. | Spain | China | Europhyt (online); TRACES (online) |

No interceptions were reported after this year.

Intercepted eight times that year.

Found on foliage.

Ceroplastes sp.

3.4.2. Establishment

Is the pest able to become established in the EU territory?

Yes, biotic factors (host availability) and abiotic factors (climate suitability) suggest that parts of the EU would be suitable for establishment. Climate types found in countries where C. rubens occurs are also found in the EU.

Based on climate matching and host availability, large parts of the EU correspond to climate types that occur in countries where C. rubens occurs.

Climatic mapping is the principal method for identifying areas that could provide suitable conditions for the establishment of a pest taking key abiotic factors into account (Baker, 2002; Baker et al., 2000). Availability of hosts is considered in Section 3.4.2.1. Climatic factors are considered in Section 3.4.2.2.

3.4.2.1. EU distribution of main host plants

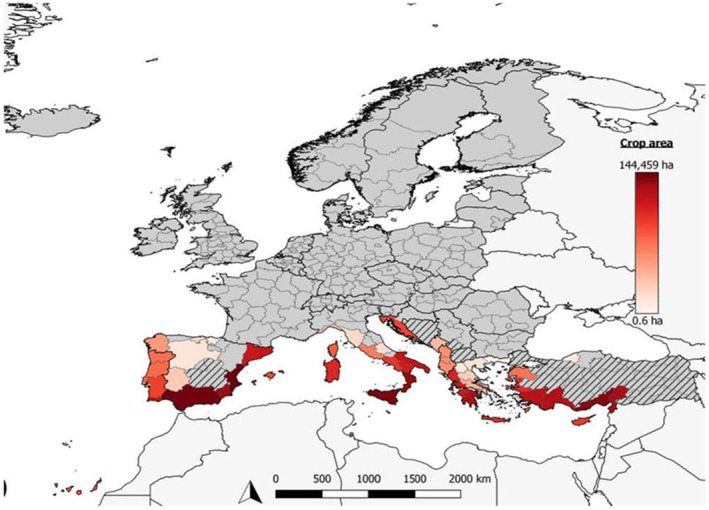

Many genera and species of C. rubens host plants are present or widely grown across the EU (e.g. Citrus spp., Ficus spp., Olea sp., Pinus spp. and Prunus sp.; Table 7, Figure 3). Its polyphagous nature (Appendix A) and wide host availability in the EU would support establishment in the EU.

TABLE 7.

Harvested area (1000 ha) of main host plants of Ceroplastes rubens in the EU. Source Eurostat (accessed on 4 January 2024).

| Crops | Code | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olives | O1000 | 5098.62 | 5071.59 | 5104 | 5008 | 4987 |

| Oranges | T1000 | 273.64 | 271.97 | 275.27 | 274.88 | 277 |

| Yellow lemons | T3100 | 78.06 | 76.37 | 80.76 | 82.17 | 84.21 |

| Figs | F2100 | 24.99 | 25.59 | 27.64 | 25.81 | 26.28 |

| Avocados | F2300 | 13.22 | 17.50 | 19.58 | 22.86 | 25.05 |

| Bananas | F2400 | 17.94 | 18.27 | 22.12 | 22.01 | 21.26 |

| Satsumas | T2100 | 8.45 | 7.69 | 7.10 | 7.04 | 6.30 |

| Pomelos and grapefruit | T4000 | 3.49 | 3.68 | 3.87 | 4.06 | 4.49 |

FIGURE 3.

European citrus‐growing areas based on data of crop area at NUTS 2 level (from EFSA PLH Panel, 2019). Areas with lines indicate regions with no data. Areas in light grey are neighbouring countries not included in the analysis.

3.4.2.2. Climatic conditions affecting establishment

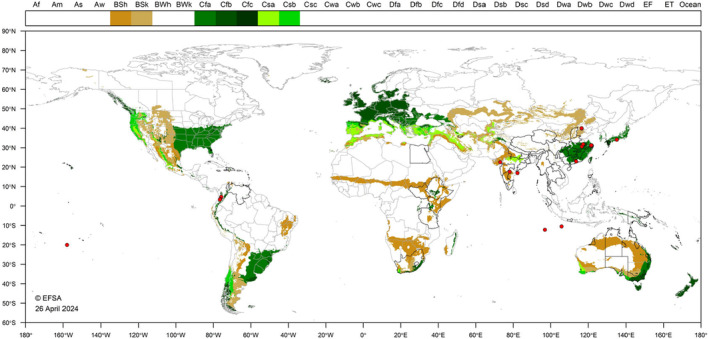

C. rubens is most frequently reported from tropical and subtropical areas of Asia, the Caribbean, Africa and Oceania. Figure 4 shows the world distribution of seven Köppen–Geiger climate types (Kottek et al., 2006) that occur in the EU and in countries where C. rubens has been reported. In northern EU, establishment may be possible in greenhouses, especially where heated.

FIGURE 4.

World distribution of the seven Köppen–Geiger climate types that occur in the EU and in countries where Ceroplastes rubens occurs (Red dots represent specific coordinate locations where C. rubens was reported).

3.4.3. Spread

Describe how the pest would be able to spread within the EU territory following establishment?

Natural spread by first instar nymphs crawling or being carried by wind, or by hitchhiking on other animals, humans or machinery, will occur locally. All stages may be moved over long distances in trade of infested plant material specifically plants for planting, cut branches and fruits.

Comment on plants for planting as a mechanism of spread.

C. rubens could be dispersed more rapidly and over long‐distances via infested plants for planting for trade.

In Japan, adult females usually overwinter in the lower parts of twigs and branches and can spread over long distances via infested plants for trade. Newly hatched nymphs usually settle on green parts of the tree and few of them disperse through the wind (Noda et al., 1982). C. rubens crawlers can spread in shorter distances through human movements, ants and animals. As they barely move naturally, they have limited dispersal activity (Malumphy, 2014). All stages are likely to disperse more rapidly and over longer distances with the movement of infested plants via trade (Malumphy et al., 2018). Dispersal can be increased by waste material, e.g. discarding whole rotten fruits via household compost (MAF Biosecurity NZ, 2007).

3.5. Impacts

Would the pests' introduction have an economic or environmental impact on the EU territory?

Yes, the introduction of C. rubens into the EU could most probably have an economic impact on orchards, amenity ornamental trees and shrubs.

C. rubens is regarded as one of the major coccid pests in tropical and subtropical areas of the world (Gill & Kosztarab, 1997). It attacks many plant species, but it is a particularly damaging pest of Citrus spp. in Australia, Hawaii, Korea, China and Japan (Malumphy, 2014). In Japan, C. rubens became a serious pest of citrus and persimmons (Diospyros kaki) following its introduction in about 1897; however, it was controlled effectively after the release of the parasitoid Anicetus beneficus Ishii & Yamumatsu (Hymenopetra: Encyrtidae) in 1948–1952 (Swirski et al., 1997). Nowadays, C. rubens may be found on citrus trees along roads which are covered with dust that protects it from parasitoid attacks (Swirski et al., 1997). Recently, C. rubens is reported as a major pest of tea plantations in northeast India, West Bengal and Sri Lanka (Kakoti et al., 2023; Sammani et al., 2023). In a recent outbreak of the pest in Sri Lanka, it was recorded infesting plant species belonging to 28 families with higher infestation densities recorded for plant species in the families Araceae (mean infestation level 9.74 ± 2.6 insects/10 cm2) and Myrtaceae (mean infestation level 9.29 ± 1.5 insects/10 cm2) (Vithana et al., 2019). It has also been reported as a pest on Pinus caribaea and P. taeda in Australia and Papua New Guinea (Merrifield & Howcroft, 1975). Adult females and nymphs feed on phloem sap causing direct damage. The production of sugary honeydew causes indirect damage on leaves and twigs, developing a layer of sooty mould fungus (Capnophaeum fuliginoides in Japan; Itioka & Inoue, 1991). This leads to low photosynthetic ability and diminished growth. Heavy infestations can result to leaf loss, necrosis of foliage, leaf discoloration, dieback and even death of susceptible host plants (Malumphy et al., 2018; Vithana et al., 2019). Fruits are also affected leading to reduced marketing value (Malumphy, 2014).

C. rubens has been recorded in the EU, in Germany (2010) in a tropical greenhouse on Aglaonema sp. (Kozár et al., 2013; Schönfeld, 2015). No impact has been officially reported after this record.

3.6. Available measures and their limitations

Are there measures available to prevent pest entry, establishment, spread or impacts such that the risk becomes mitigated?

Yes, some hosts are already prohibited from entering the EU (see Section 3.3.2). Hosts that are permitted entry require a phytosanitary certificate and a proportion of consignments is inspected. Additional options are available to reduce the likelihood of pest entry, establishment and spread into the EU (Section 3.6.1).

3.6.1. Identification of potential additional measures

Phytosanitary measures are currently applied to several host genera (e.g. prohibitions – see Section 3.3.2).

Additional potential risk reduction options and supporting measures are shown in Sections 3.6.1.1 and 3.6.1.2.

3.6.1.1. Additional potential risk reduction options

Potential additional risk reduction and control measures are listed in Table 8.

TABLE 8.

Selected control measures (a full list is available in EFSA PLH Panel, 2018) for pest entry/establishment/spread/impact in relation to currently unregulated hosts and pathways. Control measures are measures that have a direct effect on pest abundance.

| Control measure/risk reduction option (blue underline = Zenodo doc, Blue = WIP) | RRO summary | Risk element targeted (entry/establishment/spread/impact) |

|---|---|---|

| Require pest freedom | Pest‐free place of production (e.g. place of production and its immediate vicinity is free from pest over an appropriate time period, e.g. since the beginning of the last complete cycle of vegetation, or past two or three cycles) | Entry/Spread |

| Growing plants in isolation | Place of production is insect proof originate in a place of production with complete physical isolation | Entry/Spread |

| Managed growing conditions | Plants should be grown in officially registered nurseries, which are subject to an officially supervised control regime | Entry/Spread |

| Crop rotation, associations and density, weed/volunteer control | Removal of weeds around host plants is a great cultural control, as weeds are usually colonised by ants, which disturb parasitoid populations (Kabashima & Drelstadt, 2014). Crop rotation is not applicable to C. rubens host plants | Establishment/Impact |

| Use of resistant and tolerant plant species/varieties | A study by Hodges et al. (2001) showed that certain species of hollies (Illex spp.) have demonstrated a degree of resistance to Florida wax scales (C. floridensis). No studies are available targeting specifically C. rubens | Establishment/Impact |

| Roguing and pruning | Roguing (removal of infested plants) and pruning (removal of infested plant parts only without affecting the viability of the plant) can reduce the population density of the pest. During nursery inspections, any symptoms on twigs or branches of plants detected could be pruned, when feasible | Entry/Establishment/Spread/Impact |

| Biological control and behavioural manipulation |

The encyrtid parasitoid, Anicetus beneficus, a parasitoid of C. rubens with high host specificity, was released in Japan in 1948 (Yasumatsu, 1951) Successful control of C. rubens was achieved ~ 2.5 years after release of A. beneficus, reaching 60%–80% parasitism in Queensland (Smith, 1986). Noda et al. (1982) give a detailed description on the parasitisation of A. beneficus on C. rubens Apart from A. beneficus, several parasitoids have been reported In Japan, C. rubens was found on Citrus to be parasitised by Microterys speciosus, Ishii, and Coccophagus japonicus, Comp. (Smith, 1986) According to Prinsloo and Uys (2015), in South Africa, six parasitic wasps have been recorded from C. rubens on mango trees: Aprostocetus sp. prob. ceroplastae (Girault) (Eulophidae), Cheiloneurus sp. prob. cyanonotus Waterston, Metaphycus sp., Metaphycus sp. near capensis Annecke & Mynhard (all Encyrtidae), Coccophagus flaviceps Compere (Aphelinidae), Scutellista sp. (Pteromalidae) and a predatory thrip; Aleurodothrips fasciapennis (Franklin) (Daneel et al., 1994) In Florida, Scutellista cyanea is recorded as a parasite of C. rubens while in Bermuda, Microterys kotinskyi (Hamon & Williams, 1984). While using parasitoids, the control of ants is crucial, as ants are attracted by honeydew, and might suppress the number of parasitoids. Lasuis niger (common black ant) is known to attack A. beneficus in Japan (Encyrtidae, Hymenoptera) (Itioka & Inoue, 1996) |

Establishment/Spread/Impact |

| Chemical treatments on crops including reproductive material | The effectiveness of contact insecticide applications against C. rubens may be reduced by the protective wax cover over the scale. Most vulnerable is the crawler‐stage. Systemic pesticides could be effective, while contact wide range pesticides might disrupt natural enemies (Talhouk, 1978). Lu and Jiang (2015) have tested spraying with various active substances against larvae at the initial nymph stage resulting to more than 80% control (Kabashima & Drelstadt, 2014) | Entry/Establishment/Spread/Impact |

| Physical treatments on consignments or during processing |

This control measure deals with the following categories of physical treatments: irradiation/ionisation; mechanical cleaning (brushing, washing); sorting and grading, and removal of plant parts Irradiation against C. rubens is reported as postharvest control on fruits by Follett et al. (2007) |

Entry/Spread |

| Cleaning and disinfection of facilities, tools and machinery | The physical and chemical cleaning and disinfection of facilities, tools, machinery, transport means, facilities and other accessories (e.g. boxes, pots, hand tools) | Entry/Spread |

| Waste management | Treatment of the waste (deep burial, composting, incineration, chipping, production of bio‐energy…) in authorised facilities and official restriction on the movement of waste | Establishment/Spread |

| Heat and cold treatments | Controlled temperature treatments aimed to kill or inactivate pests without causing any unacceptable prejudice to the treated material itself. Vapour heat treatment, specifically, 45.2°C for 2 h is proposed by MAF Biosecurity New Zealand (2017) on imported Litchi chinensis (Litchi) fresh fruits | Entry/Spread |

| Post‐entry quarantine and other restrictions of movement in the importing country | Plants in PEQ are held in conditions that prevent the escape of pests; they can be carefully inspected and tested to verify they are of sufficient plant health status to be released, or may be treated, re‐exported or destroyed. Tests on plants are likely to include laboratory diagnostic assays and bioassays on indicator hosts to check whether the plant material is infected with pests | Entry/Spread |

3.6.1.2. Additional supporting measures

Potential additional supporting measures are listed in Table 9.

TABLE 9.

Selected supporting measures (a full list is available in EFSA PLH Panel, 2018) in relation to currently unregulated hosts and pathways. Supporting measures are organisational measures or procedures supporting the choice of appropriate risk reduction options that do not directly affect pest abundance.

| Supporting measure | Summary | Risk element targeted (entry/establishment/spread/impact) |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection and trapping |

Inspection is defined as the official visual examination of plants, plant products or other regulated articles to determine if pests are present or to determine compliance with phytosanitary regulations (ISPM 5; FAO, 2023) For Ceroplastes spp., female scales, nymphs, honeydew, sooty mould and ants can be detected during visual inspections Honeydew drippings from plants can be efficiently monitored using water‐sensitive paper, which is commonly used for monitoring insecticide droplets and calibrating (Kabashima & Drelstadt, 2014) |

Entry/Spread/Establishment |

| Laboratory testing |

Required to confirm diagnosis and identification of the pest Examination, other than visual, to determine if pests are present using official diagnostic protocols. Diagnostic protocols describe the minimum requirements for reliable diagnosis of regulated pests |

Entry/Spread |

| Sampling |

According to ISPM 31, it is usually not feasible to inspect entire consignments, so phytosanitary inspection is performed mainly on samples obtained from a consignment. It is noted that the sampling concepts presented in this standard may also apply to other phytosanitary procedures, notably selection of units for testing For inspection, testing and/or surveillance purposes the sample may be taken according to a statistically based or a non‐statistical based sampling methodology |

Entry/Spread |

| Phytosanitary certificate and plant passport |

Required to attest that a consignment meets phytosanitary import requirements a) phytosanitary certificate (imports) b) plant passport (EU internal trade) |

Entry/Spread |

| Certified and approved premises | Certification of premises to ensure the phytosanitary compliance of consignments; for example, to enable traceability and provide access to information that can help prove the compliance of consignments with phytosanitary requirements of importing countries | Entry/Spread |

| Delimitation of Buffer zones | ISPM 5 defines a buffer zone as ‘an area surrounding or adjacent to an area officially delimited for phytosanitary purposes in order to minimise the probability of spread of the target pest into or out of the delimited area, and subject to phytosanitary or other control measures, if appropriate’ (ISPM 5). The objectives for delimiting a buffer zone can be to prevent spread from the outbreak area and to maintain a pest‐free production place (PFPP), site (PFPS) or area (PFA) | Spread |

| Surveillance | Surveillance for early detection of outbreaks | Entry/Establishment/Spread |

3.6.1.3. Biological or technical factors limiting the effectiveness of measures

Wide range of host plants (e.g. making inspection of buffer zones very difficult).

Limited effectiveness of contact insecticides due to the presence of protective wax cover.

C. rubens may not be easily detected at low densities.

3.7. Uncertainty

No key uncertainties have been identified in the assessment.

4. CONCLUSIONS

Ceroplastes rubens satisfies all the criteria that are within the remit of EFSA to assess for it to be regarded as a potential Union quarantine pest (Table 10).

TABLE 10.

The Panel's conclusions on the pest categorisation criteria defined in Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 on protective measures against pests of plants (the number of the relevant sections of the pest categorisation is shown in brackets in the first column).

| Criterion of pest categorisation | Panel's conclusions against criterion in regulation (EU) 2016/2031 regarding union quarantine pest | Key uncertainties (casting doubt on the conclusion) |

|---|---|---|

| Identity of the pest (Section 3.1 ) | The identity of the species is established and Ceroplastes rubens Maskell is the accepted name | None |

| Absence/presence of the pest in the EU (Section 3.2 ) | C. rubens has been recorded in Germany, but only in a protected indoor environment (tropical greenhouse) | None |

| Pest potential for entry, establishment and spread in the EU (Section 3.4 ) | C. rubens could further enter the EU mainly via the import of host plants for planting (excluding seed) or on cut branches. Biotic factors (host availability) and abiotic factors (climate suitability) suggest that large parts of the EU would be suitable for establishment. Natural spread by first instar nymphs crawling or being carried by wind, or by hitchhiking on other animals, humans or machinery, will occur locally. C. rubens could be dispersed more rapidly and over long‐distances via infested plants for planting for trade | None |

| Potential for consequences in the EU (Section 3.5 ) | Further introduction of C. rubens into the EU could lead to outbreaks causing damage to orchard, forest, amenity ornamental trees and shrubs | None |

| Available measures (Section 3.6 ) | Some hosts are already prohibited from entering the EU. There are measures available to prevent entry, establishment and spread of C. rubens in the EU | None |

| Conclusion (Section 4 ) | C. rubens satisfies all the criteria assessed by EFSA for consideration as a potential Union quarantine pest | None |

| Aspects of assessment to focus on/scenarios to address in future if appropriate: | ||

GLOSSARY

- Containment (of a pest)

Application of phytosanitary measures in and around an infested area to prevent spread of a pest (FAO, 2023).

- Control (of a pest)

Suppression, containment or eradication of a pest population (FAO, 2023).

- Entry (of a pest)

Movement of a pest into an area where it is not yet present, or present but not widely distributed and being officially controlled (FAO, 2023).

- Eradication (of a pest)

Application of phytosanitary measures to eliminate a pest from an area (FAO, 2023).

- Establishment (of a pest)

Perpetuation, for the foreseeable future, of a pest within an area after entry (FAO, 2023).

- Greenhouse

A walk‐in, static, closed place of crop production with a usually translucent outer shell, which allows controlled exchange of material and energy with the surroundings and prevents release of plant protection products (PPPs) into the environment.

- Hitchhiker

An organism sheltering or transported accidentally via inanimate pathways including with machinery, shipping containers and vehicles; such organisms are also known as contaminating pests or stowaways (Toy and Newfield, 2010).

- Impact (of a pest)

The impact of the pest on the crop output and quality and on the environment in the occupied spatial units.

- Introduction (of a pest)

The entry of a pest resulting in its establishment (FAO, 2023).

- Pathway

Any means that allows the entry or spread of a pest (FAO, 2023).

- Phytosanitary measures

Any legislation, regulation or official procedure having the purpose to prevent the introduction or spread of quarantine pests, or to limit the economic impact of regulated non‐quarantine pests (FAO, 2023).

- Quarantine pest

A pest of potential economic importance to the area endangered thereby and not yet present there, or present but not widely distributed and being officially controlled (FAO, 2023).

- Risk reduction option (RRO)

A measure acting on pest introduction and/or pest spread and/or the magnitude of the biological impact of the pest should the pest be present. A RRO may become a phytosanitary measure, action or procedure according to the decision of the risk manager.

- Spread (of a pest)

Expansion of the geographical distribution of a pest within an area (FAO, 2023).

ABBREVIATIONS

- EPPO

European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization

- FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization

- IPPC

International Plant Protection Convention

- ISPM

International Standards for Phytosanitary Measures

- MS

Member State

- PLH

EFSA Panel on Plant Health

- PZ

Protected Zone

- TFEU

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

- ToR

Terms of Reference

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

If you wish to access the declaration of interests of any expert contributing to an EFSA scientific assessment, please contact interestmanagement@efsa.europa.eu.

REQUESTOR

European Commission

QUESTION NUMBER

EFSA‐Q‐2024‐00040

COPYRIGHT FOR NON‐EFSA CONTENT

EFSA may include images or other content for which it does not hold copyright. In such cases, EFSA indicates the copyright holder and users should seek permission to reproduce the content from the original source. Figure 1a: Courtesy of Kondo (2008); Figure 1b: Courtesy of Fera.

PANEL MEMBERS

Claude Bragard, Paula Baptista, Elisavet Chatzivassiliou, Francesco Di Serio, Paolo Gonthier, Josep Anton Jaques Miret, Annemarie Fejer Justesen, Alan MacLeod, Christer Sven Magnusson, Panagiotis Milonas, Juan A. Navas‐Cortes, Stephen Parnell, Roel Potting, Philippe L. Reignault, Emilio Stefani, Hans‐Hermann Thulke, Wopke Van der Werf, Antonio Vicent Civera, Jonathan Yuen, and Lucia Zappalà.

MAP DISCLAIMER

The designations employed and the presentation of material on any maps included in this scientific output do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Food Safety Authority concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

APPENDIX A. Ceroplastes rubens host plants/species affected

A.1.

Source: CABI CPC (CABI, online), García Morales et al. (2016) and literature.

| Scientific name | Family | Common name | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acacia | Fabaceae | – | Qin and Gullan (1994) |

| Acca sellowiana | Myrtaceae | Pineapple guava | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Acer buergerianum | Sapindaceae | Trident maple | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Acer palmatum | Sapindaceae | Japanese maple | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Acer tataricum | Sapindaceae | Tartar maple | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Acrostichum aureum | Pteridaceae | Golden leather fern; heart fern; leather fern; mangrove fern; swamp fern | CABI (online) |

| Agathis lanceolata | Araucariaceae | Koghis kauri | CABI (online) |

| Aglaonema commutatum | Araceae | Chinese evergreen; silver queen aglaonema | Moghaddam and Nematian (2021) |

| Aglaonema costatum | Araceae | Chinese evergreen; Fox's aglaonema; spotted evergreen | CABI (online) |

| Aglaonema crispum | Araceae | Painted droptongue | CABI (online) |

| Aglaonema marantifolium | Araceae | – | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Aglaonema modestum | Araceae | – | Nakahara (1981) |

| Aglaonema nitidum | Araceae | Burmese evergreen | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Aglaonema pictum | Araceae | Indonesian evergreen | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Aglaonema tricolor | Araceae | – | Hamon and Williams (1984) |

| Agonis flexuosa | Myrtaceae | Sweet willow myrtle | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Allamanda cathartica | Apocynaceae | Butter cup; common trumpetvine | Nakahara (1981) |

| Alpinia purpurata | Zingiberaceae | Red ginger | CABI (online) |

| Alstonia scholaris | Apocynaceae | Devil tree; dita bark; Indian pulai; milk wood; scholar tree | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Alternanthera dentata | Amaranthaceae | Purple‐leaved chaff flower | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Alyxia gynopogon | Apocynaceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Alyxia stellata | Apocynaceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Anacardium occidentale | Anacardiaceae | Cashew; cashew apple; cashew nut | CABI (online) |

| Annona squamosa | Annonaceae | Cuban sugar apple | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Anthurium andraeanum | Araceae | Flamingo flower | Nakahara (1981) |

| Antidesma bunius | Phyllanthaceae | China laurel | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Aralia | Araliaceae | – | Qin and Gullan (1994) |

| Ardisia humilis | Primulaceae | Low shoebutton | CABI (online) |

| Ardisia japonica | Primulaceae | Japanese ardisia | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Arillastrum gummiferum | Lithomyrtus | – | CABI (online) |

| Artemisia vulgaris | Asteraceae | Common mugwort | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Arthropteris palisotii | Tectariaceae | Lesser creeping fern | CABI (online) |

| Artocarpus altilis | Moraceae | Breadfruit | CABI (online) |

| Artocarpus heterophyllus | Moraceae | Jackfruit | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Artocarpus integer | Moraceae | Champedak | CABI (online) |

| Aspidotis | Pteridaceae | – | Qin and Gullan (1994) |

| Asplenium australasicum | Aspleniaceae | – | Qin and Gullan (1994) |

| Asplenium nidus | Aspleniaceae | Bird's‐nest fern | CABI (online) |

| Astronidium robustum | Melastomataceae | – | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Asystasia gangetica | Acanthaceae | Chinese violet; coromandel; creeping foxglove | CABI (online) |

| Atractocarpus fitzalanii | Rubiaceae | – | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Atractocarpus tahitiensis | Rubiaceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Barringtonia asiatica | Lecythidaceae | Barringtonia; bishop's cap; fish poison tree | CABI (online) |

| Barringtonia racemosa | Lecythidaceae | Cassowary pine; China pine; common putat | CABI (online) |

| Bauhinia | Fabaceae | Camel's foot | Suh and Bombay (2015) |

| Belvisia | Pteridaceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Bischofia javanica | Phyllanthaceae | Java bishopwood | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Bixa orellana | Bixaceae | Lipstick tree | Nakahara (1981) |

| Blechnum orientale | Blechnaceae | Centipede fern | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Bougainvillea | Nyctaginaceae | – | Nakahara (1981) |

| Bruguiera sexangula | Rhizophoraceae | Six‐angled orange mangrove; upriver orange mangrove | CABI (online) |

| Buxus microphylla | Buxaceae | Little‐leaf box | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Cajanus cajan | Fabaceae | Bengal pea; cajan pea; Congo pea | CABI (online) |

| Callistemon viminalis | Myrtaceae | Weeping bottlebrush | Qin and Gullan (1994) |

| Calophyllum inophyllum | Clusiaceae | Alexandrian laurel; beach calophyllum; beauty leaf | CABI (online) |

| Calophyllum tomentosum | Calophyllaceae | – | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Calyptranthes kiaerskovii | Myrtaceae | – | Malumphy et al. (2019) |

| Calyptranthes thomasiana | Myrtaceae | – | Malumphy et al. (2019) |

| Camellia japonica | Theaceae | Japanese camellia | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Camellia sasanqua | Theaceae | Christmas camellia | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Camellia sinensis | Theaceae | Tea; tea plant | CABI (online) |

| Carissa macrocarpa | Apocynaceae | Natal plum | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Cascabela thevetia | Apocynaceae | Trumpet flower | Qin and Gullan (1994) |

| Cedrus deodara | Pinaceae | Himalayan cedar | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Ceiba pentandra | Bombacaceae | Giant kapok; God's tree; kapok tree | CABI (online) |

| Celosia argentea | Amaranthaceae | Celosia; cock's‐comb; crimson cockscomb; fireweed | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Celtis | Ulmaceae | Nettle tree | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Centipeda minima | Asteraceae | Spreading sneezeweed | Suh (2020) |

| Cephalotaxus | Cephalotaxaceae | – | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Chaenomeles | Rosaceae | – | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Chrysanthemum morifolium | Asteraceae | Chrysanthemum | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Chrysophyllum caniote | Sapotaceae | Star apple | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Cibotium | Cibotiaceae | – | Nakahara (1981) |

| Cinnamomum camphora | Lauraceae | Camphor; camphor laurel; camphor tree; Japanese camphor tree | Deng et al. (2012) |

| Cinnamomum japonicum | Lauraceae | Japanese cinnamon | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Cinnamomum loureiroi | Lauraceae | – | Suh (2020) |

| Cinnamomum verum | Lauraceae | Ceylon cinnamon; cinnamon bark tree | CABI (online) |

| Citrus aurantiifolia | Rutaceae | Key lime | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Citrus deliciosa | Rutaceae | Mediterranean mandarin | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Citrus glauca | Rutaceae | Australian desert lime | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Citrus junos | Rutaceae | Yuzu | CABI (online) |

| Citrus limon | Rutaceae | Lemon | CABI (online) |

| Citrus maxima | Rutaceae | Bali lemon; pummelo | CABI (online) |

| Citrus paradisi | Rutaceae | Grapefruit | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Citrus reticulata | Rutaceae | Clementine; mandarin; tangerine | CABI (online) |

| Citrus sinensis | Rutaceae | Sweet orange | CABI (online) |

| Citrus trifoliata | Rutaceae | Golden apple | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Citrus unshiu | Rutaceae | Satsuma | CABI (online) |

| Citrus x paradisi | Rutaceae | Grapefruit | CABI (online) |

| Cleyera japonica | Pentaphylacaceae | Japanese cleyera | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Coccoloba uvifera | Polygonaceae | Common sea grape; Jamaica kino; platter leaf; sea grape | CABI (online) |

| Cocos nucifera | Arecaceae | Coconut; coco palm; common coconut palm | CABI (online) |

| Coffea arabica | Rubiaceae | Arabian coffee; coffee tree | CABI (online) |

| Coffea liberica | Rubiaceae | Liberian coffee | CABI (online) |

| Coprosma laevigata | Rubiaceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Cryptocarya triplinervis | Lauraceae | – | Qin and Gullan (1994) |

| Cupaniopsis serrata | Sapindaceae | – | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Cycas circinalis | Cycadaceae | Fern palm | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Cycas media | Cycadaceae | Australian nut palm | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Cycas revoluta | Cycadaceae | Japanese fern palm | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Cycas thouarsii | Cycadaceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Cytisus scoparius | Fabaceae | Scottish broom | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Daphne odora | Thymelaeaceae | Winter daphne | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Davallia | Polypodiaceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Denhamia cunninghamii | Celastraceae | – | Qin and Gullan (1994) |

| Dicranopteris flexuosa | Gleicheniaceae | Forked fern | Nakahara and Miller (1981) |

| Dicranopteris linearis | Gleicheniaceae | Old World forked fern; scrambling fern | CABI (online) |

| Dieffenbachia seguine | Araceae | Dumb cane; mother‐in‐law plant; poison arum | CABI (online) |

| Dieffenbachia | Araceae | – | Nakahara (1981) |

| Dimocarpus longan | Sapindaceae | Dragon's eye; longan | Wen et al. (2002) |

| Dioclea violacea | Fabaceae | Nakahara (1981) | |

| Diospyros digyna | Ebenaceae | – | Qin and Gullan (1994) |

| Diospyros kaki | Ebenaceae | Chinese date plum; Chinese persimmon; Japanese persimmon; kaki | CABI (online) |

| Distylium racemosum | Hamamelidaceae | Isu tree | Suh (2020) |

| Dizygotheca elegantissima | Araliaceae | False aralia | CABI (online) |

| Dracaena | Agavaceae | – | Suh and Bombay (2015) |

| Elaeocarpus bifidus | Elaeocarpaceae | – | Nakahara (1981) |

| Elaeocarpus sylvestris | Elaeocarpaceae | – | Suh (2020) |

| Elaeodendron | Celastraceae | – | Qin and Gullan (1994) |

| Elaphoglossum crassifolium | Dryopteridaceae | – | Nakahara (1981) |

| Epipremnum pinnatum | Araceae | Centipede tonga vine; devil's ivy; golden pothos; hunter's robe; marble queen | CABI (online) |

| Eriobotrya japonica | Rosaceae | Japanese medlar |

García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Eucalyptus globulus | Myrtaceae | Southern blue gum | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Eugenia uniflora | Myrtaceae | Surinam cherry | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Eugenia luehmanni | Myrtaceae | Lillipilly | Hackman and Trikojus (1952) |

| Euonymus alatus | Celastraceae | Burning bush | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Euonymus europaeus | Celastraceae | Common spindle | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Euonymus japonicus | Celastraceae | Japanese spindle | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Euphorbia heterophylla | Euphorbiaceae | Mexican fire plant | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Euphorbia pulcherrima | Euphorbiaceae | Christmas flower; Christmas star; common poinsettia | CABI (online) |

| Euphorbia pulcherrima | Euphorbiaceae | Mexican fire plant | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Eurya emarginata | Pentaphylacaceae | – | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Eurya japonica | Pentaphylacaceae | – | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Exocarpos phyllanthoides | Santalaceae | – | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Fatsia japonica | Araliaceae | Fatsia; Formosa rice tree | Deng et al. (2012) |

| Feijoa | Myrtaceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Ficus amplissima | Moraceae | – | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Ficus benjamina | Moraceae | Benjamin's fig |

García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Ficus carica | Moraceae | Common fig; fig | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Ficus citrifolia | Moraceae | García Morales et al. (2016) | |

| Ficus elastica | Moraceae | Assam rubber tree; Indian rubber fig | CABI (online) |

| Ficus glandifera | Moraceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Ficus microcarpa | Moraceae | Indian laurel | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Ficus montana | Moraceae | – | Williams and Miller (2010) |

| Ficus prolixa | Moraceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Fitchia | Asteraceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Flindersia australis | Rutaceae | Australian teak | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Flindersia bennettii | Rutaceae | – | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Flindersia bourjotiana | Rutaceae | Queensland silver ash | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Flindersia brayleyana | Rutaceae | Queensland maple | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Flindersia schottiana | Rutaceae | Cudgerie | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Garcinia amplexicaulis | Clusiaceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Garcinia gummi‐gutta | Clusiaceae | Basavaraju et al. (2021) | |

| Garcinia indica | Clusiaceae | Basavaraju et al. (2021) | |

| Garcinia mangostana | Clusiaceae | Mangosteen | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Garcinia morella | Clusiaceae | Ceylon gamboge | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Garcinia myrtifolia | Clusiaceae | – |

CABI (online) |

| Garcinia spicata | Clusiaceae | – |

García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Garcinia subelliptica | Clusiaceae | – | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Gardenia jasminoides | Rubiaceae | Cape jasmine; Cape jessamine; common gardenia | CABI (online) |

| Gardenia taitensis | Rubiaceae | Tahitian gardenia | Nakahara (1981) |

| Gerbera jamesonii | Asteraceae | African daisy | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Gleichenia | Gleicheniaceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Grammatophyllum | Orchidaceae | – | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Hedera helix | Araliaceae | Common ivy; English ivy | CABI (online) |

| Hedera rhombea | Araliaceae | Japanese ivy | Suh (2020) |

| Helianthus | Asteraceae | Sunflower | CABI (online) |

| Heliconia | Heliconiaceae | CABI (online) | |

| Heptapleurum actinophyllum | Araliaceae | – | Nakahara (1981) |

| Hernandia nymphaeifolia | Hernandiaceae | Sea hearse | CABI (online) |

| Hibiscus mutabilis | Malvaceae | Confederate rose mallow | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Hibiscus rosa‐sinensis | Malvaceae | China rose; Chinese hibiscus; Chinese rose; Hawaiian hibiscus | CABI (online) |

| Hibiscus tiliaceus | Malvaceae | Coast hibiscus; cottonwood; hau tree; linden hibiscus | CABI (online) |

| Hydrangea paniculata | Hydrangeaceae | Panicle hydrangea | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Ilex aquifolium | Aquifoliaceae | Panicle hydrangea | Nakahara (1981) |

| Ilex chinensis | Aquifoliaceae | Kashi holly | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Ilex cornuta | Aquifoliaceae | Chinese holly; horned holly | Deng et al. (2012) |

| Ilex crenata | Aquifoliaceae | Japanese holly | Suh (2020) |

| Ilex integra | Aquifoliaceae | Mochi | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Ilex latifolia | Aquifoliaceae | Tarajo | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Ilex pedunculosa | Aquifoliaceae | Long‐stalk holly | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Ilex rotunda | Aquifoliaceae | Round‐leaf holly | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Ilex serrata | Aquifoliaceae | Japanese winterberry | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Illicium anisatum | Schisandraceae | Japanese star anise | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Impatiens balsamina | Balsaminaceae | Garden balsam | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Inocarpus fagifer | Fabaceae | Otaheite chestnut; Polynesian chestnut; Tahiti chestnut | CABI (online) |

| Iris domestica | Iridaceae | Blackberry lily | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Ixora chinensis | Rubiaceae | Flame of the woods | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Ixora coccinea | Rubiaceae | Jungle flame | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Kadsura japonica | Schisandraceae | Evergreen magnolia vine | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Lagerstroemia indica | Lythraceae | Cannonball; carrion tree; crepe myrtle | CABI (online) |

| Laurus nobilis | Lauraceae | Apollo laurel; bay; Greek laurel | CABI (online) |

| Leucopogon | Ericaceae | – | CABI (online) |

| Ligustrum japonicum | Oleaceae | Japanese privet | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Ligustrum obtusifolium | Oleaceae | Border privet | CABI (online) |

| Lindera citriodora | Lauraceae | – | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Litchi chinensis | Sapindaceae | Litchee; litchi | Malumphy et al. (2018) |

| Lophostemon confertus | Myrtaceae | Brisbane box | Qin and Gullan (1994) |

| Loranthus | Loranthaceae | – | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Machilus thunbergii | Lauraceae | Makko | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Maclura cochinchinensis | Moraceae | Cockspur‐thorn | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Macropiper excelsum | Piperaceae | Kawakawa | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Magnolia denudata | Magnoliaceae | Magnolia yulan; yulan | CABI (online) |

| Magnolia salicifolia | Magnoliaceae | Willow‐leaved magnolia | Gimpel et al. (1974) |

| Mallotus japonicus | Euphorbiaceae | Food wrapper plant | Suh (2020) |

| Malus sylvestris | Rosaceae | Wild apple | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Mangifera indica | Anacardiaceae | Mango | Vithana et al. (2019) |

| Manilkara bidentata | Sapotaceae | Bullet tree; bulletwood; cherry mahogany | Merrifield and Howcroft (1975) |

| Melaleuca bracteata | Myrtaceae | Black tea tree | Qin and Gullan (1994) |

| Melaleuca leucadendra | Myrtaceae | Weeping paperbark | Qin and Gullan (1994) |

| Melaleuca nodosa | Myrtaceae | – | García Morales et al. (2016) |

| Melaleuca quinquenervia | Myrtaceae | Paperbark tea tree | Qin and Gullan (1994) |