Abstract

Previous studies with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection of rhesus macaques suggested that the intrinsic susceptibility of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) to infection with SIV in vitro was predictive of relative viremia after SIV challenge. The present study was conducted to evaluate this parameter in a well-characterized cohort of six rhesus macaques selected for marked differences in susceptibility to SIV infection in vitro. Rank order relative susceptibility of PBMC to SIVsmE543-3-infection in vitro was maintained over a 1-year period of evaluation. Differential susceptibility of different donors was maintained in CD8+ T-cell-depleted PBMC, macrophages, and CD4+ T-cell lines derived by transformation of PBMC with herpesvirus saimiri, suggesting that this phenomenon is an intrinsic property of CD4+ target cells. Following intravenous infection of these macaques with SIVsmE543-3, we observed a wide range in plasma viremia which followed the same rank order as the relative susceptibility established by in vitro studies. A significant correlation was observed between plasma viremia at 2 and 8 weeks postinoculation and in vitro susceptibility (P < 0.05). The observation that the two most susceptible macaques were seropositive for simian T-lymphotropic virus type 1 may suggests a role for this viral infection in enhancing susceptibility to SIV infection in vitro and in vivo. In summary, intrinsic susceptibility of CD4+ target cells appears to be an important factor influencing early virus replication patterns in vivo that should be considered in the design and interpretation of vaccine studies using the SIV/macaque model.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection of humans is a fatal disease in the vast majority of patients, with a median survival of about 10 years from the time of diagnosis. However, the disease course in HIV-infected patients is highly variable, ranging from long-term asymptomatic survival for over 15 years (4, 8, 46) to rapid progression to AIDS within 1 or 2 years of infection (32, 38, 39, 42). Of particular interest are those patients that remain healthy, the long-term nonprogressors (4, 46). Persistent replication of virus is observed throughout infection (10, 47, 56). The level at which plasma viremia stabilizes following primary HIV infection is a highly significant prognostic indicator of subsequent disease course (37, 45), suggesting that host immune mechanisms in the early period after seroconversion are critical in the control of viremia. Indeed, the development of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) specific for HIV occurs concurrently with a decrease in primary plasma viremia, consistent with a role of CD8+ CTL in controlling virus replication (26, 41). The reasons behind nonprogression are unclear but encompass both host and viral factors. Host factors that influence disease progression include deletions in the chemokine coreceptor gene (CCR5) (8, 54), strength of the CTL response (23, 26, 41, 44), strength of the antibody response (33), and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I haplotype (5, 15). In addition, factors such as the biologic phenotype of the infecting virus, coreceptor usage, or attenuating mutations such as nef gene deletions in the infecting viral strain may also influence the rate of disease progression (7, 12). The rate of evolution of the HIV-1 envelope varies depending on the rate of disease progression of the patient (36). The viral strains, dose, and route of infection are highly variable among HIV-infected patients, making analysis of the contributions of host mechanisms to differences in disease progression complex.

Animal model systems are critical for gaining an in-depth understanding of the pathogenesis of AIDS. Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection of macaques is a highly relevant model for these types of studies since it induces an immunodeficiency syndrome that is remarkably similar to that seen in HIV-infected humans (1–3, 17, 28, 29, 35, 58). The median survival time of SIV-infected macaques is considerably shorter than for HIV-infected humans, ranging from 1 to 2 years depending on the strain of virus (1, 17). Like HIV-1-infected humans, SIV-infected macaques exhibit variable disease course even when inoculated with a common molecularly cloned virus (19, 20, 24). This is consistent with a strong influence of host factors on disease expression. There is also evidence from sequential studies that the virus can evolve in terms of virulence during the course of infection (9, 25). The majority of SIV-inoculated animals develop progressive disease and succumb to AIDS over a 1- to 2-year period. However, a few SIV-inoculated macaques exhibit low levels of virus replication and develop a nonprogressive infection, and a few progress rapidly to AIDS in a period of less than 6 months. These latter animals characteristically do not develop SIV-specific antibodies and exhibit persistent high levels of viral replication (17, 18, 55, 58).

As observed in humans infected with HIV-1, the postseroconversion viral load or viral load set point is also a strong predictor of disease progression in the SIV/macaque model (18, 55). The rate of development of viremia and the peak levels during primary viremia also appear to correlate with disease progression (31, 43, 52). The decrease in plasma viremia after seroconversion is coincident with the development of a CD8+ CTL response in SIV-infected macaques (27). Consistent with a role for CTL in controlling viremia, in vivo depletion of CD8+ T cells by administration of antibody results in higher levels of viremia and more rapid progression following SIV challenge of macaques (27). MHC class I haplotype also appears to influence the rate of disease progression (11) but has been studied far less intensively than in HIV-infected humans. There is also emerging evidence that the strength of the CTL response in macaques influences the viral set point and thereby disease progression. The percentage of CD8+ T cells that bind the MHC class 1/peptide tetramer in SIV-infected macaques that express the MHC class I allele Mamu-A*01 correlates inversely with the level of postseroconversion plasma viremia (51). These data suggest that the strength of the CTL response may be predictive of plasma viral set point and subsequent disease progression. Previous studies have suggested that there also may be nonimmune mechanisms responsible for some of the disease variability among SIV-infected macaques (31). A retrospective study revealed that the in vitro susceptibility of mitogen-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) of individual macaques to infection with SIV was predictive of the subsequent levels of plasma viremia (31). This study found no significant differences relative proportions of CD4+ T cells or in the expression of chemokines. Preliminary analysis suggested that the differences in intrinsic susceptibility were a property of the CD4+ target cells rather than a CD8 suppressor phenomenon.

In this study, we expanded on this previous observation by extensively characterizing in vitro susceptibility to SIV infection in longitudinal samples from a small cohort of macaques prior to challenge with a pathogenic SIV strain. The influence of MHC haplotype and CTL response to disease progression was considered as a separate issue. The purpose of this study was to confirm whether in vitro susceptibility was an accurate predictor of subsequent in vivo viral replication in macaques and to determine the cellular mechanisms responsible for differences in susceptibility to SIV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

A cohort of 22 Indian-origin rhesus macaques from a single commercial source were screened for in vitro susceptibility to SIVsmE543-3 as described below. Six rhesus macaques were selected for further study. Macaques were screened for coinfection with herpesvirus B virus, rhesus cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, simian type D retrovirus, SIV, and simian T-lymphotropic virus type 1 (STLV-1). All were seronegative for simian type D retrovirus and SIV and seropositive for all herpesviruses evaluated. Two animals (444 and 445) were seropositive for STLV-1. Animals were housed in accordance with federal guidelines (42). Macaques were inoculated intravenously with 1 ml of cell-free SIVsmE543-3 (10,000 50% tissue culture infective doses [TCID50]) and monitored sequentially for virus isolation from PBMC, plasma viral RNA levels antibodies by Western blot analysis, histopathology, and flow cytometric analysis of lymphocyte subsets.

In vitro susceptibility assay.

PBMC were separated by centrifugation through Ficoll (lymphocyte separation medium) and resuspended in RPMI 1640 with 5 μg of phytohemagglutinin (PHA) per ml, 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), and 10% interleukin-2 (IL-2) at a density of 2 × 106 PBMC per ml. Three to four days after initial culture, aliquots of 2 × 106 PBMC were incubated for 1 h with 1 ml of serial 10-fold dilutions of a cell-free virus stock of SIVsmE543-3 that was generated by transfection of CEMx174 cells. PBMC were washed with Hanks balanced salt solution to remove residual virus, resuspended in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS and 10% IL-2, and cultured in 48-well tissue culture plates. Culture supernatant were collected at days 0, 3, 7, 10, 14, and 17 after infection and monitored for the presence of virus by reverse transcriptase (RT) assay and antigen capture assay for SIV p27 antigen (Coulter Corp.). The minimal TCID or endpoint titer of virus required to infect the cells of different donors was determined as the last dilution in which virus was detected by 17 days after infection.

Infection of CD8+-depleted PBMC or monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM).

CD8+ cells were depleted from some PBMC cultures using two sequential incubations with CD8 Dynabeads (Dynal) on freshly separated PBMC prior to addition of PHA. The degree of CD8 depletion was assessed by flow cytometry for CD3, CD4, and CD8 markers prior to culture of the cells and at the time of infection. Macrophage cultures were prepared as previously described (19). Briefly, PBMC were plated in wells of a 24-well tissue culture plate at a density of 107 cells in RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS and 10% normal macaque serum. At 4 days, adherent macrophages were washed extensively with Hanks balanced salt solution to remove residual lymphocytes and infected with serial dilutions of virus. Cultures were confirmed to be 98% macrophages by α-naphthyl acetate esterase stain (Sigma Diagnostics, St. Louis, Mo.) and immunohistochemistry using antibody to Ham56. Supernatants were assessed in parallel for RT activity and p27 antigen.

Viruses and cell lines.

The majority of studies were performed with the molecularly cloned pathogenic SIVsmE543-3 (19). In vitro susceptibility to SIVmac251 was also assessed. T-cell lines were derived from each of the six macaques by transformation of CD8+ T-cell-depleted PBMC with herpesvirus saimirii (HVS; a gift from R. C. Desrosiers) generated by infection of OMK 637 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.). For transformation, PBMC were incubated with 1 ml of virus stock, washed, and seeded into 12-well plates in RPMI 1640 with 20% FCS and a 1:256,000 dilution of β-mercaptoethanol. PBMC were fed with 50% medium changes twice weekly and transferred to T25 flasks after 2 to 3 weeks in medium containing 10% IL-2 (Hemagen), when the cells began to proliferate and were slowly expanded.

Proliferation assay.

PBMC were separated on Ficoll (in lymphocyte separation medium), suspended in RPMI 1640 at a density of 106 cells per ml, and aliquoted into a 96-well tissue culture plate at 100 μl per well. Cells were incubated in the presence of 10% human AB serum with or without the addition of mitogens. Titrations of 0.5, 1, and 2 μg of concanavalin A (Sigma), Staphylococcus endotoxin A (ICN), pokeweed mitogen (Gibco/BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.), and PHA were performed to select the optimal concentration of each mitogen. Data shown in Table 2 are results of a proliferation assay using 5 μg of PHA per ml plus 10% IL-2, the concentrations of these reagents used for the in vitro susceptibility assay. PBMC were incubated for 6 days at 37°C and then incubated with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine for 18 h. Cells were harvested the next day, and the incorporation of [3H]thymidine was assayed. The mean value of six wells of resting cells was compared to the mean value obtained with mitogen (six wells) to obtain a stimulation index, and the standard deviation was calculated.

TABLE 2.

Susceptibility phenotype is a property of CD4+ T cells and macrophages

| Macaque | Log10 TCID in:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| PBMCa | CD8− PBMCb | MDM | |

| 458 | 1.3 | 1.5 (0.9) | 2 |

| 447 | 0.1 | <1.0 (2.6) | <1 |

| 460 | 3.6 | 4.0 (2.8) | 4 |

| 444 | 5.0 | 5.0 (2.8) | 4 |

| 445 | 4.6 | 4.0 (2.0) | NDc |

Mean TCID from three independent experiments.

Mean TCID from two independent experiments. Numbers in parentheses are percentages of CD8+ T cells in cultures at the time of infection in one experiment.

ND, not determined.

Flow cytometry.

Lymphocyte subsets in PBMC and transformed T-cell lines were analyzed by flow cytometry using a Coulter EPICS cell sorter. Monoclonal antibodies used included CD3-phycoerythrin (PE) (a gift from P. R. Johnson, New England Regional Primate Research Center), OKT4-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) for CD4 (Ortho Diagnostics), Leu2a-FITC or -peridinin chlorophyll protein for CD8 (Becton Dickinson), CCR5-FITC (2D7; Leukosite), CD45RA-PE-Cy5 (Serotec), CD62L-PE (Leu8; Becton Dickinson), and HLA-DR-PE (Becton Dickinson). DR was used as a marker for activation on gated CD3+ or CD4+ T cells.

RESULTS

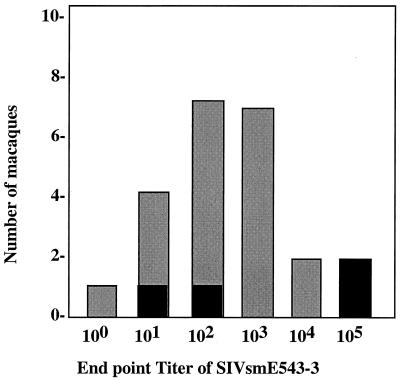

A total of 22 rhesus macaques were tested to assess variability in intrinsic susceptibility of their PBMC to SIVsmE543-3. Equal numbers of PBMC from each donor were infected with serial 10-fold dilutions of SIVsmE543-3 from undilute to a 1:1,000,000 dilution as described in Materials and Methods. The production of virus was assessed longitudinally by production of RT activity and SIV p27 antigen in culture supernatants, and a minimal TCID was determined for each donor. The TCID of a common stock of SIVsmE543-3 varied as much as 4 orders of magnitude (Fig. 1), depending on the donor PBMC used for the infectivity titration. The maximal TCID achieved for this virus stock in macaque PBMC was approximately 105 per ml, comparable to the infectivity observed in the highly susceptible CEMx174 cell line (data not shown). The TCIDs of donor PBMC followed a roughly Gaussian distribution as shown in Fig. 1, with the majority of macaques having an intermediate phenotype. Interestingly, two of the most susceptible donors were also seropositive for STLV-1. However, serology of the entire cohort revealed that two additional macaques of intermediate susceptibility phenotype were also seropositive for STLV-1. Thus, STLV-1 infection per se was not associated with increased susceptibility to SIV infection in vitro.

FIG. 1.

Bar graph of the distribution of in vitro susceptibility of PBMC of 22 macaques as assessed by relative TCID of the SIVsmE543-3 stock. STLV-1-seropositive macaques are indicated with black bars; STLV-1-negative macaques are indicated with shaded bars.

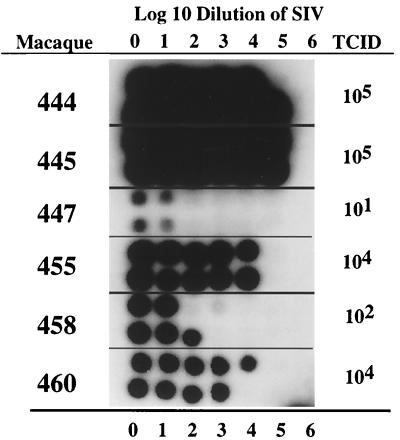

Six macaques with the most diverse range in susceptibility (444, 445, 447, 455, 458, and 460) were chosen for further study. The titer of SIVsmE543-3 in PBMC of these six macaque donors varied from 105 per ml (444 and 445) to 1 per ml (447), with a rank order of susceptibility of 444 = 445 > 460 > 455 > 458 > 447 (Table 1 and Fig. 2). These donors were also evaluated in parallel for susceptibility to SIVmac251 (Fig. 3); the rank order of susceptibility remained the same as observed with SIVsmE543-3, although the maximum titer achieved was lower (104 per ml for 444 and 445). This difference in the maximal titer between the two stocks is reflective of relative infectious titers of the two stocks. The susceptibility phenotype of these six donors was stable over a period of at least 1 year, as shown by the results of endpoint titrations performed at three separate times points in Table 1. Indeed the endpoint titers determined from different bleeds were remarkably consistent in terms of the rank order of susceptibility, with the most variation occurring in PBMC from macaques of intermediate phenotype (particularly 455).

TABLE 1.

Sequential evaluation of intrinsic in vitro susceptibility of macaque PBMC donors by determination of minimal TCID of SIVsmE543-3

| Macaque | Log10 minimal TCID/mla

|

Peak SIV p27 (ng/ml) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Expt 3 | Mean | ||

| 444 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 182.0 |

| 445 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 55.0 |

| 460 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 10.0 |

| 455 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 6.1 |

| 458 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 6.2 |

| 447 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

Determined as the last of a serial 10-fold duplicate dilution of SIVsmE543-3 to result in infection of PBMC as measured by RT activity and/or SIV p27 antigen in culture supernatants.

FIG. 2.

RT activity in culture supernatants collected at 11 days postinfection from PBMC of six macaques infected with serial 10-fold dilutions of SIVsmE543-3. Numbers at the top and bottom represent the log10 dilution of virus input (i.e., 6 = 106). The minimal TCIDs for these six donors are shown to the right.

FIG. 3.

Correlation between TCID of SIVsmE543-3 or SIVmac251 in six donors. The bar graph shows relative TCIDs of these two stocks in a representative experiment where all infections were performed in parallel. This result was confirmed in two independent experiments.

Not only did the donor PBMC vary in terms of relative susceptibility to SIV as determined by endpoint titers, but variation was also observed in the amount of virus produced during infection. The differential in virus production is evident in the differences in intensity of RT activity in a representative experiment in Fig. 2 and as assessed by peak p27 antigen levels in culture supernatants summarized in Table 1. PBMC cultures from the two highly susceptible animals produced considerably (almost 1,000-fold) more virus than those from the most resistant donor (0.2 versus 182 ng/ml), with macaques 460, 455, and 458 being intermediate. In the least susceptible donors (458 and 447), virus was initially detected in culture supernatants early after infection but subsequently declined to baseline levels. One of these donors (447) was remarkably resistant to infection with SIV even when undiluted virus of at least 105 TCID per ml was used for infection (Fig. 2). Resistance to infection was repeatedly observed in 10 independent infection experiments with this particular donor.

Differential susceptibility is a property of CD4+ target cells.

To determine whether resistance to SIV infection in the two most resistant donors (458 and 447) was due to CD8 suppressor factors, infections were performed using CD8-depleted PBMC. As shown in Table 2, depletion of CD8+ lymphocytes had no effect on the TCID of SIVsmE543 in the more resistant macaque's PBMC. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that low proportions of CD8+ T lymphocytes remained in these cultures. Sequential flow cytometry of these cultures revealed that the relative proportion of CD8+ T cells increased over time after infection, with no apparent difference between donors (data not shown). A second depletion of CD8+ T cells from cultures at 3 days after SIV infection had no effect on the relative susceptibility of the cultures. MDM from these resistant macaques (458 and 447) were also highly resistant, whereas MDM from 444 and 460 were highly susceptible to infection with SIVsmE543-3 (Table 2). These cultures were not evaluated by flow cytometry for residual CD8+ T cells, but T cells would be unlikely to survive for the over 14 days in the absence of IL-2 or PHA.

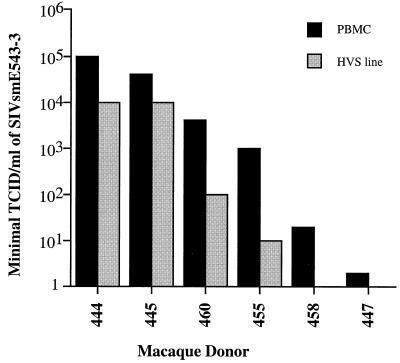

To confirm that the resistant phenotype was a property of the CD4+ target cells of individual macaques, T-cell lines of each donor were derived by transformation of CD8+-depleted PBMC with HVS. Flow cytometry of the resulting T-cell lines as summarized in Table 3 revealed that the majority (93 to 98%) of lymphocytes in these cultures expressed CD4, with a low proportion (1 to 6.4%) of CD8+ T cells. CD8 depletion was used to remove residual CD8+ lymphocytes (<1%) prior to infection. PCR analysis using HTLV/STLV-specific gag primers revealed that the T-cell lines from the STLV-positive macaques did not contain STLV provirus (data not shown). Susceptibility of each of the HVS lines was assessed in parallel with PBMC cultures from the cohort using the limiting dilution assay. As shown in Fig. 4, the relative susceptibility of these T-cell lines was similar to that of PBMC from the same donors. Thus, the rank order in susceptibility was the same as observed with PBMC cultures although the titers achieved were overall 10-fold lower.

TABLE 3.

Lymphocyte subset analysis of HVS-transformed T-cell lines from six different rhesus macaque donors

| Macaque | % of lymphocytes of indicated phenotype

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ | CD8+ | CD3+ | CD3+ T cells

|

||||

| DR+ | 45RA+ | 45RA+ 62L+ | CCR5+ | ||||

| 444 | 98.7 | 1.0 | 98.9 | 11.8 | 98.2 | 23.0 | 8.6 |

| 445 | 93.4 | 6.4 | 99.2 | 8.3 | 98.8 | 19.0 | 10.8 |

| 460 | 95.8 | 3.6 | 98.8 | 19.8 | 98.3 | 26.3 | 24.4 |

| 455 | 94.3 | 5.1 | 97.6 | 16.8 | 97.2 | 22.4 | 15.6 |

| 458 | 97.5 | 1.9 | 97.9 | 22.6 | 97.2 | 13.4 | 27.8 |

| 447 | 94.7 | 5.0 | 98.7 | 4.2 | 97.9 | 14.6 | 7.9 |

FIG. 4.

Correlation between susceptibility to SIVsmE543-3 of PBMC and HVS-transformed T-cell lines. The bar graph shows relative TCIDs of SIVsmE543 in PBMC and HVS lines of the six macaques.

Characterization of PBMC and HVS lines.

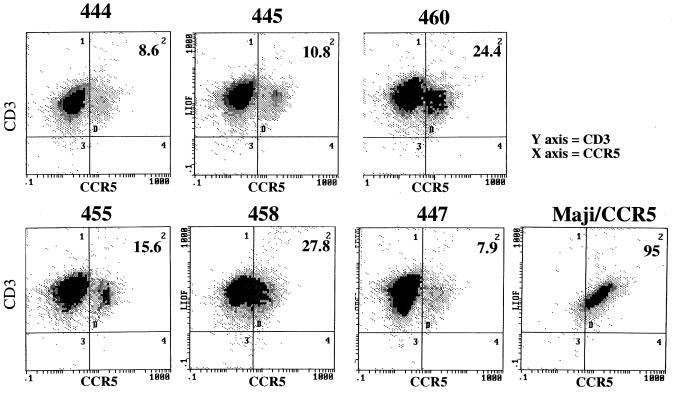

To determine whether there were major differences in the percentage of CD4+ T cells, CCR5 expression, or T-cell activation in these six macaques, flow cytometry on PBMC and HVS-transformed cell lines was performed as summarized in Tables 3 and 4. For the PBMC samples, the percentage of CD4+ T cells ranged from 36.1 to 64.1%. No consistent differences in the percentage of CD4+ T cells or in the proportion of activated (DR+), CD3+, or CD4+ T cells were observed. No consistent pattern of activation markers were observed among the HVS lines. The percentage of CD3+ or CD4+ T cells that expressed the DR antigen also varied (12.2 to 30.4%), with no apparent correlation between the percentage of DR-expressing cells and intrinsic susceptibility. For example, 445 and 447, which had highly diverse susceptibility phenotypes, had similar levels of DR expression of CD3+ T cells. Likewise, the frequency of CD3+ cells that coexpressed CD45RA and CD62L, which are markers believed to be expressed by naive T cells, also varied widely (7.1 to 47.6% of CD3+ T cells). We were particularly interested to determine whether variation in the expression of CCR5, a major coreceptor for SIV, might explain the differences in susceptibility. Expression of CCR5 on HVS-transformed cell lines from the six donors varied (Table 3 and Fig. 5); however, a higher level of expression did not correlate with a higher degree of susceptibility. For example, 445, one of the most susceptible donors, had one of the lowest percentage of T cells expressing CCR5. Thus, differential expression of CCR5 is unlikely to explain the observed differences in SIV susceptibility.

TABLE 4.

Lymphocyte subset analysis of PBMC from rhesus macaques

| Macaque | % of lymphocytes of indicated phenotype

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4+ | CD8+ | CD4+ CD8+ | CD4+ DR+ | CD3+ T cells

|

||||

| CD3+ | DR+ | CD45RA+ | 45RA+ 62L+ | |||||

| 444 | 64.1 | 27.0 | 1.1 | 22.7 | 75.6 | 30.4 | 74.3 | 47.6 |

| 445 | 37.4 | 52.2 | 1.2 | 19.8 | 82.7 | 12.2 | 81.0 | 18.6 |

| 460 | 36.1 | 36.9 | 1.1 | 18.4 | 58.8 | 29.8 | 52.7 | 17.5 |

| 455 | 39.8 | 43.4 | 4.1 | nd | 85.0 | 18.3 | 82.6 | 20.4 |

| 458 | 53.2 | 33.0 | 3.3 | 16.4 | 66.8 | 20.7 | 63.7 | 7.1 |

| 447 | 44.1 | 49.1 | 1.8 | 14.1 | 92.1 | 12.2 | 89.4 | 11.9 |

FIG. 5.

Flow cytometric analysis of CD3+ T cells in HVS-transformed T-cell lines for expression of CCR5 using monoclonal antibody 2D7. The percentage of cells expressing CCR5 is shown at the top right of each panel. Analysis of the Maji/CCR5 cell line is shown on the bottom right as a positive control for staining of CCR5.

We reasoned that PBMC from the most resistant donors (458 and 447) might not be responding adequately to the mitogens (PHA and IL-2) used for activation. Differential responses of CD4+ T cells to mitogens could have a major impact on infectivity of PBMC cultures. The ability of PBMC from the six donors to proliferate upon exposure to mitogens such as concanavalin A, PHA, and Staphylococcus enterotoxin B was evaluated using thymidine incorporation as a measure of cell proliferation. All donor PBMCs responded vigorously to each of these mitogens; the response to PHA in one representative experiment is summarized in Table 5. High baseline proliferation of PBMC in the absence of mitogens was observed for three of the donors (444, 445, and 455). Such an increase could indicate a high proportion of activated cells in PBMC from these donors. However, comparison of baseline proliferation of PBMC of donor 444 and 447 on five separate occasions (1,690 and 1,806 cpm, respectively) revealed no significant difference. Critically, PBMC from the two most resistant donors appeared to be fully competent to proliferate in response to mitogens. Therefore, the resistance of PBMC from macaques 458 and 447 is unlikely to be due to the inability to respond to mitogen stimulation.

TABLE 5.

Resistance of PBMC to SIV infection is not accounted for by differential response to mitogen stimulation

| Macaque | cpma

|

Stimulation index (Mean cpm with PHA/mean cpm with medium alone) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medium alone | PHA + IL-2 | ||

| 444 | 1,790 ± 847 | 74,300 ± 8,185 | 41 |

| 445 | 4,420 ± 536 | 263,580 ± 11,631 | 59 |

| 460 | 160 ± 41 | 203,340 ± 9,612 | 1,270 |

| 455 | 990 ± 553 | 126,510 ± 5,376 | 127 |

| 458 | 170 ± 106 | 86,130 ± 14,100 | 506 |

| 447 | 140 ± 39 | 114,940 ± 8,632 | 821 |

Mean of six individual wells ± standard deviation.

Levels of plasma viremia correlate with intrinsic susceptibility.

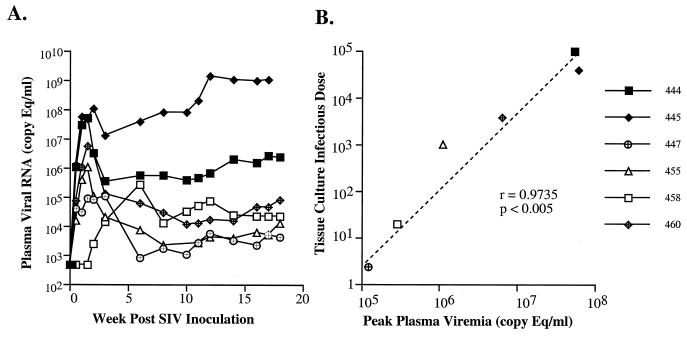

The six macaques were inoculated intravenously with equivalent amounts of SIVsmE543-3 and monitored for seroconversion, recovery of infectious virus from PBMC cultures, and plasma viral RNA levels. All macaques became persistently infected, as evidenced by rescue of infectious virus from their PBMC by cocultivation with CEMx174 cells (data not shown). However, the success of recovery of infectious virus from the two least susceptible donors was considerably less than for the other four macaques. Each of the animals developed SIV-specific antibodies as well as SIV Gag and/or Env-specific CTL by 3 weeks postinoculation (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 6A, plasma viremia monitored over the first 18 weeks of infection was highly variable, ranging from <500 copy eq/ml to >108 copy eq/ml. The rank order in viral load was the same as observed for in vitro susceptibility. The data were analyzed by Spearman rank correlation coefficient analysis (Fig. 6B and Table 6). A highly significant correlation was observed between the intrinsic susceptibility (as assessed by TCID) and plasma viremia at either peak primary viremia (r = 0.9429, P < 0.01), 2 weeks (r = 0.9429, P < 0.01), or 8 weeks (r = 0.8857, P < 0.05) postinoculation. Although primary plasma viremias in animals 444, and 445, the two most susceptible macaques, were indistinguishable, their viral load set points established by 8 weeks postinoculation differed by 2 orders of magnitude (106 versus 108). Macaque 445 mounted only a transient antibody and CTL response. This animal developed persistent diarrhea and wasting that necessitated euthanasia at 16 weeks postinoculation, a disease course characteristic of rapid progression. This result suggests that although intrinsic susceptibility can have a major role in determining the degree of initial plasma viremia, immune responses are clearly capable of modulating subsequent viremia to various degrees in different individuals.

FIG. 6.

Plasma viremia and the correlation between plasma viremia and in vitro susceptibility. (A) Plasma viremia in the cohort of six macaques is shown graphically over the first 18 weeks after inoculation. Plasma samples were collected at 0, 3, 7, 10, 14, 17, 21, and 28 days and every 2 weeks thereafter. (B) The statistically significant correlation observed between peak primary plasma viremia and TCID determined in vitro is shown in a scatter plot.

TABLE 6.

Spearman rank correlation coefficient analysis of plasma viral load and intrinsic susceptibility of macaques

| Macaque | TCID | Plasma viral RNA after SIV inoculation

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 wk | 8 wk | Peak | ||

| 444 | 100,000 | 54,000,000 | 6,100,000 | 54,000,000 |

| 445 | 40,000 | 51,000,000 | 91,000,000 | 63,000,000 |

| 460 | 4,000 | 6,300,000 | 31,000 | 6,300,000 |

| 455 | 1,000 | 1,100,000 | 2,400 | 1,100,000 |

| 458 | 20 | 2,700 | 14,000 | 280,000 |

| 447 | 3 | 98,000 | 1,800 | 120,000 |

| r | 0.943 | 0.886 | 0.943 | |

| P | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.01 | |

DISCUSSION

The mechanistic basis for differences in disease course among HIV-infected humans and SIV-infected macaques is obviously complex and multifactorial, encompassing both host and viral factors. The present study focused mainly on intrinsic, nonimmune host factors that influence disease course in SIV infection. We demonstrate that the CD4+ T cells of different rhesus macaques can vary significantly in susceptibility to infection by SIV in vitro. The different phenotypic properties of macaque PBMC cultures are stable over long periods of time. Most importantly, this property correlates significantly with the susceptibility of these macaques to SIV infection in vivo. The correlation between in vivo viremia and in vitro susceptibility is the most robust during primary viremia, consistent with previous observations that the extent of early viremia is predictive of disease course (31, 51). These data suggest that this phenomenon is stable property of the CD4+ target cells of the macaques and exerts its effect separate from the effects of the immune response to the virus.

Infection with STLV-1 was an extrinsic factor that could potentially affect virus and diseases susceptibility in this small cohort of macaques. The two most susceptible macaques were persistently infected with STLV-1. STLV-1 infection by producing T-lymphocyte activation could potentially increase the number of susceptible CD4+ target cells. Higher level of proliferation of resting PBMC from the two STLV-positive macaques may be consistent with an increased proportion of activated cells in these animals. However, similar assays performed at other times did not reveal consistent increases in baseline proliferation of PBMC of these macaques compared to other animals of the cohort. Similarly, flow cytometric analysis of the two STLV-1-infected macaques did not demonstrate unusually high proportions of DR+ T cells. Studies of the T-cell repertoire revealed clonal expansions primarily within the CD8+ T-cell population of all six macaques; such expansions are indicative of some degree of immune activation (6), consistent with serologic evidence of concurrent infections such as Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and STLV-1. However, there was no evidence for an unusual degree of immune activation in the STLV-infected macaques (444 and 445). Thus, while STLV-1 infection cannot be ruled out as influencing susceptibility to SIV infection of these two animals, a number of lines of evidence suggest that STLV-1 infection may be a coincidental finding in this study. First, not all STLV-1-infected macaques evaluated for susceptibility to SIV showed the marked increase susceptibility seen for macaques 444 and 445 (Fig. 1). Two additional STLV-infected macaques actually were relatively resistant to SIV infection in vitro. Second, the HVS-transformed T-cell lines of these highly susceptible macaques did not contain STLV-1 provirus and yet retained the highly susceptible phenotype. Third, there is considerable precedent in the literature that infection of macaques with STLV-1 or humans with HTLV-1 does not enhance viral load or disease progression associated with SIV or HIV, respectively (13, 14). The association between STLV-1 infection and increased susceptibility in vitro and in vivo clearly warrants further prospective studies.

We propose that disease progression in SIV infection of macaques is a complex multifactorial process. In this model, intrinsic susceptibility of CD4+ T cells would be the major determinant of the amount of viremia during primary infection. Immune activation at the time of SIV infection such as induced by concurrent infections might also influence the level of viremia. However, divergence in the effectiveness of cytotoxic T-cell responses and neutralizing antibody in two macaques with similar primary viremia might lead to considerable divergence in the establishment of plasma viral RNA set point. Superimposed over the immune response to the virus would be the evolution of virus within each individual and the potential emergence of more virulent variants, as observed previously for SIVmne (25) and SIVmac/BK28 (8), or neutralization and cytotoxic T-cell escape mutants. Thus, the relative susceptibility of each macaque is not necessarily predictive of the overall virologic and disease outcome. The most obvious example of the impact of immune response was observed with the two most susceptible macaques. These two macaques exhibited very similar kinetics and levels of primary viremia. However, one macaque (444) mounted an effective neutralizing antibody and cytotoxic T-cell response (S. Santra and V. Hirsch, unpublished observations), and viremia subsequently stabilized at approximately 106/ml (2 logs lower than primary viremia). This macaque has survived for 1 year with moderately high viremia and slowly declining CD4+ T-cell counts. The other macaque (445) exhibited a transient immune response and increasing levels of plasma viremia and rapidly developed a wasting syndrome by 16 weeks after SIV inoculation. Sequential CTL and neutralizing antibody responses in this cohort are being examined and may explain some of the inconsistencies between in vitro and in vivo viral replication.

The cellular mechanism that underlies in vitro and in vivo susceptibility to SIV infection of rhesus macaques is not clear. This study suggests that susceptibility to SIV infection is an intrinsic property of CD4+ T cells and macrophage target cells rather than a CD8 suppressor cell phenomenon. Preliminary studies of viral entry using a PCR-based assay suggest that viral replication in resistant macaque PBMC is blocked at a step following viral entry. Since the phenomenon is observed both in vitro and during primary infection, differences in susceptibility are unlikely to be due to differences in MHC class I haplotype and/or differential efficacy of the cellular immune response of the animals. Some potential mechanisms to be considered include differential expression or allelic polymorphism of cellular factors that interact with or are required for virus replication. This includes any of the critical coreceptors (CCR5, Bob, and Bonzo) or cellular factors that interact with Tat, Rev, Vpr, Vif, or preintegration complexes. Further studies will be required to define the stage(s) in the viral replication study affected in PBMC from resistant donors compared to susceptible donors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part with funds from the National Cancer Institute under contract NO1-CO-56000.

We thank R. Byrum, M. St. Claire, and Boris Skopets, Bioqual, Inc., for assistance with the animal studies, R. C. Desrosiers for the gift of HVS, and FAST Systems for flow cytometric analysis of macaque samples.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allan J S. Pathogenic properties of simian immunodeficiency viruses in nonhuman primates. Annu Rev AIDS Res. 1991;1:191–206. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baskin G B, Murphey-Corb M, Watson E A, Martin L N. Necropsy findings in rhesus monkeys experimentally infected with cultured simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV/Delta) Vet Pathol. 1988;25:456–467. doi: 10.1177/030098588802500609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benveniste R E, Arthur L O, Tsai C-C, Sowder R, Copeland T D, Henderson L E, Oroszlan S. Isolation of a lentivirus from a macaque with lymphoma: comparison with HTLV-III/LAV and other lentiviruses. J Virol. 1986;60:483–490. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.2.483-490.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cao Y, Qin L, Zhang L, Safrit J, Ho D. Virologic and immunologic characterization of long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:201–208. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrington M, Nelson G W, Martin M P, Kissner T, Vlahov D, Goedert J J, Kaslow R, Buchbinder S, Hoots K, O'Brien S J. HLA and HIV-1: heterozygote advantage and B*35-Cw*04 disadvantage. Science. 1999;283:1748–1752. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5408.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Currier J R, Stevenson K S, Kehn P J, Zheng K, Hirsch V M, Robinson M A. Contributions of CD4+, CD8+, and CD4+CD8+ T cells to skewing within the peripheral T cell receptor β-chain repertoire of healthy macaques. Hum Immunol. 1999;60:209–222. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(98)00109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deacon N J, Tsykin A, Solomon A, Smith K, Ludford-Menting M, Hooker D J, McPhee D A, Greenway A L, Ellett A, Chatfield C, et al. Genomic structure of an attenuated quasi species of HIV-1 from a blood transfusion donor and recipients. Science. 1995;270:988–991. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley G A, Smith M W, Allikmets R, Goedert J J, Buchbinder S P, Vittinghoff E, Gomperts E, Donfield S, Vlahov D, Kaslow R, Saah A, Rinaldo C, Detels R, O'Brien S J. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Science. 1996;273:1856–1862. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edmonson P, Murphey-Corb M, Martin L N, Delahunty C, Heeney J, Kornfeld H, Donahue R P, Learn G H, Hood L, Mullins J I. Evolution of a simian immunodeficiency virus pathogen. J Virol. 1998;72:405–414. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.405-414.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Embertson J, Zupancic J L, Ribas J, Haase A. Massive covert infection of helper T lymphocytes by HIV during the incubation period of AIDS. Science. 1994;259:359–362. doi: 10.1038/362359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans D T, Knapp L A, Jing P, Mitchen J L, Dykhuizen M, Montefiori D C, Pauza C D, Watkins D I. Rapid and slow progressors differ by a single MHC class I haplotype in a family of MHC-defined rhesus macaques infected with SIV. Immunol Lett. 1999;66:53–59. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fenyo E M, Albert J, Asjo B. Replicative capacity, cytopathic effect and cell tropism of HIV. AIDS. 1989;3(Suppl. 1):S5–S12. doi: 10.1097/00002030-198901001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fultz P N, McGinn T, Davis I C, Romano J W, Li Y. Coinfection of macaques with simian immunodeficiency virus and simian T cell leukemia virus type I: effects on viral burden and disease progression. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:600–611. doi: 10.1086/314627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison L H, Quinn T C, Schechter M. Human T cell lymphotropic virus type I does not increase human immunodeficiency virus load in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:438–440. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.2.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hendel H, Caillat-Zucman S, Lebuanec H, Carrington M, O'Brien S, Andrieu J M, Schachter F, Zagury D, Rappaport J, Winkler C, Nelson G W, Zagury J F. New class I and II HLA alleles strongly associated with opposite patterns of progression to AIDS. J Immunol. 1999;162:6942–6946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirsch V M, Olmsted R A, Murphey-Corb M, Purcell R H, Johnson P R. An African primate lentivirus (SIVsmm) closely related to HIV-2. Nature. 1989;339:389–391. doi: 10.1038/339389a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirsch V M, Johnson P R. Pathogenic diversity of simian immunodeficiency viruses. Virus Res. 1994;32:183–203. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(94)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirsch V M, Fuerst T R, Sutter G, Carroll M W, Yang L C, Goldstein S, Piatak M, Elkins W R, Alvord W G, Montefiori D C, Moss B, Lifson J D. Patterns of viral replication correlate with outcome in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaques: effect of prior immunization with a trivalent SIV vaccine in modified vaccinia virus Ankara. J Virol. 1996;70:3741–3752. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3741-3752.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirsch V M, Adger-Johnson D, Campbell B, Goldstein S, Brown C, Elkins W R, Montefiori D C. A molecularly cloned pathogenic neutralization-resistant simian immunodeficiency virus, SIVsmE543-3. J Virol. 1997;71:1608–1615. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1608-1620.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirsch V M, Dapolito G, Hahn A, Lifson J D, Montefiori D, Brown C R, Goeken R. Viral genetic evolution in macaques infected with molecularly cloned simian immunodeficiency virus correlates with the extent of persistent viremia. J Virol. 1998;8:6482–6489. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6482-6489.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirsch V M, Sharkey M E, Brown C R, Brichacek B, Goldstein S, Wakefield J, Byrum R, Elkins W R, Hahn B H, Lifson J D, Stevenson M. Vpx is required for dissemination and pathogenesis of SIVsmPBj: evidence for macrophage-dependent viral amplification. Nat Med. 1998;4:1401–1408. doi: 10.1038/3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho D, Neumann A U, Perelson A S, Chen W, Leonard J M, Markowitz M. Rapid turnover of plasma virions and CD4 lymphocytes in HIV-1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:123–126. doi: 10.1038/373123a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawana A, Tomiyama H, Takiguchi M, Shioda T, Nakamura T, Iwamoto A. Accumulation of specific amino acid substitutions in HLA-B35-restricted human immunodeficiency virus type 1 cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1999;15:1099–2107. doi: 10.1089/088922299310395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kestler H W, Kodama T, Ringler D, Marthas M, Pederson N, Lackner A, Rieger D, Seghal P, Daniel M, King N, Desrosiers R C. Induction of AIDS in rhesus monkeys by molecularly cloned simian immunodeficiency virus. Nature. 1988;248:1109–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.2160735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimata J T, Kuller L, Anderson D B, Dailey P, Overbaugh J. Emerging cytopathic and antigenic simian immunodeficiency virus variants influence AIDS progression. Nat Med. 1999;5:535–541. doi: 10.1038/8414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koup R A, Safrit J T, Cao Y, Andrews C A, McLeod G, Borkowsky W, Farthing C, Ho D D. Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J Virol. 1994;68:4650–4655. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4650-4655.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuroda M J, Schmitz J E, Charini W A, Nickerson C E, Lifton M A, Lord C I, Forman M A, Letvin N L. Emergence of CTL coincides with clearance of virus during primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus monkeys. J Immunol. 1999;162:5127–5133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Letvin N L, Daniel M D, Seghal P K, Desrosiers R C, Hunt R D, Waldron L M, MacKey J J, Schmidt D K, Chalifoux L V, King N W. Induction of AIDS-like disease in macaque monkeys with T-cell tropic retrovirus STLV-III. Science. 1985;230:71–73. doi: 10.1126/science.2412295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Letvin N L, King N. Immunopathologic and pathologic manifestations of the infection of rhesus monkeys with simian immunodeficiency virus of macaques. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr. 1990;3:1023–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lifson J D, Piatak M. Quantitative PCR techniques. Natick, Mass: Eaton Publishing; 1997. pp. 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lifson J D, Nowak M, Goldstein S, Rossio J, Kinter A, Vasquez G, Wiltrout T A, Brown C, Schneider D, Wahl L, Lloyd A, Elkins W R, Fauci A S, Hirsch V M. The extent of early virus replication is a critical determinant of the natural history of AIDS virus infection. J Virol. 1997;71:9508–9514. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9508-9514.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu S L, Schacker T, Musey L, Shriner D, McElrath M J, Corey L, Mullins J I. Divergent patterns of progression to AIDS after infection from the same source: human immunodeficiency virus type 1 evolution and antiviral responses. J Virol. 1997;71:4284–4295. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4284-4295.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loomis-Price L D, Cox J H, Mascola J R, VanCott T C, Michael N L, Fouts T R, Redfield R R, Robb M L, Wahren B, Sheppard H W, Birx D L. Correlation between humoral responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope and disease progression in early-stage infection. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1306–1316. doi: 10.1086/314436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luciw P A, Shaw K E, Unger R E, Planelles V, Stout M W, Lackner J E, Pratt-Lowe E, Leung N J, Banapour B, Marthas M L. Genetic and biological comparisons of pathogenic and nonpathogenic molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVmac) AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1992;8:395–402. doi: 10.1089/aid.1992.8.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McClure H M, Anderson D C, Fultz P N, Ansari A A, Lockwood E, Brodie A. Spectrum of disease in macaques monkeys chronically infected with SIVsmm. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1989;21:13–24. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(89)90126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDonald R A, Mayers D L, Chung R C, Wagner K F, Ratto-Kim S, Birx D L, Michael N L. Evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env sequence variation in patients with diverse rates of disease progression and T-cell function. J Virol. 1997;71:1871–1879. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1871-1879.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mellors J W, Rinaldo C R, Jr, Gupta P, White R M, Todd J A, Kingsley L A. Prognosis in HIV-1 infection predicted by the quantity of virus in plasma. Science. 1996;272:1167–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michael N L, Brown A E, Voigt R F, Frankel S S, Mascola J R, Brothers K S, Louder M, Birx D L, Cassol S A. Rapid disease progression without seroconversion following primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection—evidence for highly susceptible human hosts. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1352–1359. doi: 10.1086/516467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montagnier L, Brenner C, Chamaret S, Guetard D, Blanchard A, de Saint Martin J, Poveda J D, Pialoux G, Gougeon M L. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and AIDS in a person with negative serology. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:955–959. doi: 10.1086/513999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murphey-Corb M, Martin L N, Rangan S R S, Baskin G B, Gormus B J, Wolf R H, Andes W A, West M, Montelaro R C. Isolation of an HTLV-III-related retrovirus from macaques with simian AIDS and its possible origin in asymptomatic mangabeys. Nature. 1986;321:435–437. doi: 10.1038/321435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Musey L, Hughes J, Schacker T, Shea T, Corey L, McElrath M J. Cytotoxic-T-cell responses, viral load, and disease progression in early human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1267–1274. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710303371803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Research Council. Guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nowak M A, Lloyd A L, Vasquez G M, Wiltrout T A, Wahl L M, Bischofberger N, Williams J, Kinter A, Fauci A S, Hirsch V M, Lifson J D. Viral dynamics of primary viremia and antiretroviral therapy in simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 1997;71:7518–7525. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7518-7525.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Brien T R, Blattner W A, Waters D, Eyster E, Hilgartner M W, Cohen A R, Luban N, Hatzakis A, Aledort L M, Rosenberg P S, Miley W J, Kroner, B. L. B L, Goedert J J. Serum HIV-1 RNA levels and time to development of AIDS in the Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study. JAMA. 1996;276:105–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ogg G S, Kostense S, Klein M R, Jurriaans S, Hamann D, McMichael A J, Miedema F. Longitudinal phenotypic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes: correlation with disease progression. J Virol. 1999;73:9153–9160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9153-9160.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Panteleo G, Menzo S, Vaccarezza M, Graziosi C, Cohen O J, Demarest J F, Montefiori D, Orenstein J M, Fox C, Schrager L K, Margolick J B, Buchbinder S, Giorgi J V, Fauci A S. Studies in subjects with long-term nonprogressive human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:209–216. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501263320402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piatak M, Saag M S, Yang L C, Clark S J, Kappes K C, Luk K C, Hahn B H, Shaw G M, Lifson J D. High levels of HIV-1 in plasma during all stages of infection determined by competitive PCR. Science. 1993;259:1749–1754. doi: 10.1126/science.8096089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piatak M, Wages J, Luk K-C, Lifson J D. Competitive RT PCR for quantification of RNA: theoretical considerations and practical advice. In: Krieg P A, editor. A laboratory guide to RNA: isolation, analysis, synthesis. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1996. pp. 191–221. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reimann K A, Watson A, Dailey P J, Lin W, Lord C I, Steenbeke T D, Parker R A, Axthelm M K, Karlsson G B. Viral burden and disease progression in rhesus monkeys infected with chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency viruses. Virology. 1999;256:15–21. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmitz J E, Kuroda M J, Santra S, Sasseville V G, Simon M A, Lifton M A, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Dalesandro M, Scallon B J, Ghrayeb J, Forman M A, Montefiori D C, Rieber E P, Letvin N L, Reimann K A. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science. 1999;283:857–860. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seth A, Ourmanov I, Schmitz J E, Kuroda M J, Lifton M A, Nickerson C E, Wyatt L, Carroll M, Moss B, Venzon D, Letvin N L, Hirsch V M. Immunization with a modified vaccinia virus expressing simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) Gag-Pol primes for an anamnestic Gag-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response and is associate with reduction of viremia after SIV challenge. J Virol. 2000;74:2502–2509. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2502-2509.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Staprans S I, Dailey P J, Rosenthal A, Horton C, Grant R M, Lerche N, Feinberg M B. Simian immunodeficiency virus disease course is predicted by the extent of virus replication during primary infection. J Virol. 1999;73:4829–4839. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4829-4839.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suryanarayana K, Wiltrout T A, Vasquez G M, Hirsch V M, Lifson J D. Plasma SIV RNA viral load by real time quantification of product generation in RT PCR. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1998;14:183–189. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Unutmaz D, KewalRamani V N, Littman D R. G-protein coupled receptors in HIV and SIV: new perspectives on lentivirus-host interactions and on the utility of animal models. Semin Immunol. 1998;10:225–236. doi: 10.1006/smim.1998.0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watson A, Ranchalis J, Travis B, McClure J, Sutton W, Johnson P R, Hu S L, Haigwood N L. Plasma viremia in macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus: plasma viral load early in infection predicts survival. J Virol. 1997;71:284–2890. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.284-290.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wei X, Ghosh S K, Taylor M E, Johnson V A, Emini E A, Deutsch P, Lifson J D, Bonhoeffer S, Nowak M A, Hahn B H, Saag M S, Shaw G W. Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature. 1995;373:117–122. doi: 10.1038/373117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yin C, Wu M S, Pauza C D, Salvato M S. High major histocompatibility complex-unrestricted lysis of simian immunodeficiency virus envelope-expressing cells predisposes macaques to rapid AIDS progression. J Virol. 1999;73:3692–3701. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3692-3701.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang J, Martin L N, Warson E A, Montelaro R C, West M, Epstein L, Murphey-Corb M. Simian immunodeficiency virus/Delta-induced immunodeficiency disease in rhesus monkeys: relation of antibody response and antigenemia. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:1277–1286. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.6.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]