Abstract

PURPOSE

The experience of ethnically diverse parents of children with serious illness in the US health care system has not been well studied. Listening to families from these communities about their experiences could identify modifiable barriers to quality pediatric serious illness care and facilitate the development of potential improvements. Our aim was to explore parents’ perspectives of their children’s health care for serious illness from Somali, Hmong, and Latin-American communities in Minnesota.

METHODS

We conducted a qualitative study with focus groups and individual interviews using immersion-crystallization data analysis with a community-based participatory research approach.

RESULTS

Twenty-six parents of children with serious illness participated (8 Somali, 10 Hmong, and 8 Latin-American). Parents desired 2-way trusting and respectful relationships with medical staff. Three themes supported this trust, based on parents’ experiences with challenging and supportive health care: (1) Informed understanding allows parents to understand and be prepared for their child’s medical care; (2) Compassionate interactions with staff allow parents to feel their children are cared for; (3) Respected parental advocacy allows parents to feel their wisdom is heard. Effective communication is 1 key to improving understanding, expressing compassion, and partnering with parents, including quality medical interpretation for low–English proficient parents.

CONCLUSIONS

Parents of children with serious illness from Somali, Hmong, and Latin-American communities shared a desire for improved relationships with staff and improved health care processes. Processes that enhance communication, support, and connection, including individual and system-level interventions driven by community voices, hold the potential for reducing health disparities in pediatric serious illness.

Key words: pediatric health care, health disparities, qualitative research, community-based participatory research, communication

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, nearly 500,000 children live with a serious or life-threatening illness,1,2 defined by the Institute of Medicine as those who carry a substantial probability of death in childhood, although treatment may succeed in curing the condition or substantially prolonging life, and are perceived as potentially having fatal outcomes.3 Family caregivers of children with serious illness are challenged by managing intense medical needs,4,5 navigating a complex health system and significant time demands,6 and becoming medical experts and parent advocates.7 Consequences for parents of children with serious illness include increased psychological distress, higher risk of developing symptoms of depression and anxiety, and increased risk for persisting psychiatric morbidity, particularly among those with prior stressful or traumatic experiences.8

Racially and ethnically diverse families, limited– or non–English speaking families, and families with lower socioeconomic status experience disparities across the spectrum of pediatric health care, including health status, mortality rates, access to care and use of services, and quality of care.9-11 There is a large knowledge gap in understanding the health care experience among racially and ethnically diverse parents of children with serious illness.12 Engaging parents who are underrepresented in pediatric serious illness research has the potential to identify modifiable factors that may be contributing to health inequities.

We conducted this community-based participatory research study to explore Somali, Hmong, and Latin American (SHL) parents’ experiences of pediatric serious illness care and identify their perspectives about what could improve health care for their children.

METHODS

Approach

We utilized a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach because it effectively engages community members in the research process as full partners and builds upon communities’ knowledge, expertise, and resources.13 CBPR has been shown to improve trustworthiness of research results, increase the likelihood that interventions will be applicable, acceptable, sustainable and disseminated broadly, and address health disparities.14

Our CBPR research team included a Somali female nurse (A.A.), Hmong female community health worker (S.L.), Latino male physician (R.B.), Latina female nurse (P.P.), Asian male graduate student (J.C.), White female public health researcher (S.P.), and 2 White female physicians (J.N., K.A.C-P). All but 1 research team member (J.N.) were members of SoLaHmo Partnership for Health and Wellness, a community-driven research program. We worked as a central research team, with 3 community-specific teams that included 1 or more language-concordant members: Somali (A.A., S.P., J.N.), Hmong (S.L., K.A.C-P.), and Latin-American (R.B., P.P., S.P.). We partnered with a community advisory board (CAB) consisting of SHL community leaders and parents, which gave input on study design, data analysis, and recommendations. The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board approved the study (00015786 Approved 6/22).

Setting and Recruitment

We recruited participants through clinician referrals, flyers, social media, and community networks in the Minneapolis-Saint Paul, Minnesota metropolitan area. SHL research team members discussed the study with interested people in their preferred language (Hmong, Somali, Spanish, or English) and evaluated inclusion criteria, including adults aged ≥18 years; from an SHL community; spoke English, Somali, Hmong, or Spanish; and caregiver/parent of a child with a serious illness, defined as illnesses and conditions that pose a significant risk of death and impose physical and emotional distress during the illness trajectory.15

Data Collection

Researchers obtained participants’ consents, completed demographic surveys, and scheduled participants for a focus group or individual interviews if unable to attend a focus group. Researchers conducted 1.5- to 2-hour community-specific focus groups or individual interviews on Zoom (Zoom Video Communications Inc) or by phone in participants’ preferred languages. We designed structured interview guides based on literature review, professional and community knowledge, and CAB input. The interview guides (translated into Hmong, Somali, and Spanish) inquired about parents’ positive and negative experiences with health care experiences and their recommendations for improvement. All interviews were audio-recorded, anonymized, translated into English, and transcribed. Researchers tried to engender trust by speaking participants’ language and asserting expectations of confidentiality and respect at the beginning of focus groups and interviews.

Data Analysis

For qualitative data analysis, we used an immersion/crystallization analysis16 process to identify common aspects of parents’ experiences across all 3 communities and a participatory approach17 to bring community expertise into each step of analysis. These 2 intertwined processes involved repeated interactions between the culturally specific sub-teams and the full team, with input from the CAB. In the initial immersion/crystallization step, the 3 sub-teams immersed themselves in their first transcript by reading, reflecting, taking notes, and discussing their emerging ideas, until they agreed upon 3 to 5 major ideas about parents’ experiences. The full team explored and discussed all sub-teams’ major ideas until we identified major ideas across all 3 communities, which became a coding tree. Each team used the coding tree to analyze each subsequent transcript, discussing and adjusting the codes as relevant. The full team iteratively identified and reorganized the data into major themes and sub-themes that were shared across all 3 communities and chose illustrative quotes. Given the small sample size, we did not analyze the data by parents’ characteristics, data collection methods (focus group or individual interview), nature or severity of children’s illnesses, or extent of health care experiences. When the importance of parents’ education and English language skills became evident, however, we analyzed the data by education and English ability. Finally, we identified recommendations to improve parental experiences based on parents’ recommendations as well as the full team and CAB’s interpretations of parents’ positive and negative experiences.

RESULTS

Participants’ Characteristics

Twenty-six parents participated, including 8 Somali, 10 Hmong, and 8 Latin American parents. All but 1 participants were mothers (96%). By self-report, 58% spoke excellent/good English, and 42% had limited English proficiency (LEP). Twenty-one parents attended 1 of 7 focus groups and 5 parents had individual interviews. Participants’ children included 6 infants, 14 children, 2 adolescents, and 3 adults who had a range of serious illness diagnoses and functional status, including 38% with feeding tubes, 4% with ventilatory support, and 1 infant who died 2 weeks before the study. Fourteen of the children were hospitalized in the last 6 months and 7 had consulted with palliative care (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants and Their Children

| Parents | Total (n = 26) | Somali (n = 8) | Hmong (n = 10) | Latin American (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median years (range) | 38 (26-62) | 39 (28-53) | 37 (26-62) | 38 (27-46) |

| Gender, % female | 96 | 100 | 90 | 100 |

| Method, % | ||||

| Focus group | 81 | 75 | 90 | 75 |

| Individual interview | 19 | 25 | 10 | 25 |

| Highest education, % | ||||

| None and primary school | 8 | 0 | 10 | 12 |

| High school | 50 | 75 | 10 | 75 |

| College and graduate degree | 42 | 24 | 80 | 12 |

| English proficiency, % | ||||

| Excellent/good | 58 | 38 | 90 | 38 |

| Fair/poor (limited English proficiency) | 42 | 62 | 10 | 62 |

| Religion, % | ||||

| Animist | 19 | 0 | 50 | 0 |

| Christian-Catholic | 15 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| Christian-Protestant | 12 | 0 | 50 | 13 |

| Muslim | 31 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Children | ||||

| Current age category, % | ||||

| Infant (<1 y) | 23 | 26 | 10 | 38 |

| Child (1-13 y) | 57 | 50 | 60 | 62 |

| Adolescent (14-21 y) | 8 | 12 | 10 | 0 |

| Adult (≥21 y) | 12 | 12 | 20 | 0 |

| Primary diagnosis category, % | ||||

| Consequences of prematurity | 8 | 13 | 0 | 12 |

| Cardiac | 15 | 25 | 10 | 12 |

| Neurologic/cognitive impairment | 35 | 38 | 40 | 26 |

| Renal | 11 | 12 | 10 | 12 |

| Genetic condition | 23 | 4 | 30 | 26 |

| Cancer | 8 | 0 | 10 | 12 |

| Technology dependent, % yes | 38 | 50 | 40 | 25 |

| Hospitalized last 6 months, % yes | 54 | 88 | 40 | 38 |

| Received palliative care, % yes | 27 | 50 | 20 | 25 |

Themes

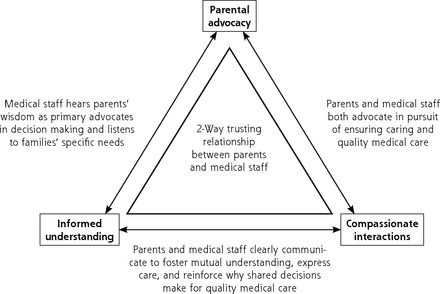

Somali, Hmong, and Latin-American parents had an overarching desire for 2-way trusting and respectful relationships with medical staff. Three distinct but interrelated themes contributed to enhancing 2-way trusting respectful relationships: informed understanding, compassionate interactions, and respected parental advocacy (Figure 1) (Supplemental Table 1 for expanded illustrative quotes).

Figure 1.

Interrelated themes contributing to enhancing 2-way trusting respectful relationships.

Theme 1. Informed Understanding

Parents praised and criticized aspects of staff communication that impacted 2-way trusting respectful relationships. Parents were grateful for staff who took the time to explain medical diagnoses and recommended treatments in simple English, and/or worked with interpreters so that parents understood the medical perspectives. Parents with a clear understanding of their child’s medical situation were more able to trust the medical team. Parents shared how medical jargon presented challenges as they navigated the complexity of a child’s serious illness.

Even if they talk to us in our language the medical terminology is hard to understand, and if it is in a different language it is even worse. (Latin-American-7)

Universally, parents with LEP highlighted the critical roles that interpreters play in communication and understanding. They shared how they often did not trust the information that was being presented, that interpreters were not communicating the gravity of the situation, or that interpreters were not accurately relaying parents’ questions and desires for more information. To overcome this interpreter-communication barrier, parents resorted to utilizing trusted English-proficient family members.

He didn’t mention my daughter’s condition was critical. I ended up getting upset when I realize the interpreter wasn’t saying exactly what the doctor was mentioning. (Somali-3)

Parents expressed how they were often overwhelmed by their medical experiences, feeling unprepared for what to expect. Lack of preparedness led to feelings of mistrust, especially when parents perceived that information was being withheld or misrepresented. Similarly, lack of consistent plans between the medical team contributed to parents’ lack of trust.

(F)or parents like me with children with these problems, that they need to explain to us what the future of our children will be, but they (need to) explain with better words. (Latin-American-2)

Theme 2. Compassionate Interactions

Parents shared they were more trusting of staff when they experienced that staff cared about them, paid attention to their cultural and religious needs, provided quality care, and did not treat them poorly because of their race, ethnicity, or language. Caring connections eased parents’ feelings of fear about their child’s health, and feelings of alienation.

(The NICU nurse) was just so loving toward my daughter…and I knew that my daughter was in good hands. (Hmong-9)

Parents felt grateful when staff expressed caring with respect to their cultural and religious traditions. Parents struggled with maintaining their cultural and religious traditional healing practices in the face of highly technological modern medicine. Acceptance of the role of traditional healing improved parents’ trust in the health care team.

By the time the nurse wheeled me to the NICU the Quran was already playing. This was one of the best feelings I have ever experienced. (Somali-1)

Some parents recalled how staff expressed negative attitudes toward them, acted disrespectfully, disregarded their cultural and religious practices, or spoke abusively to the child. Parents described their experiences with racism that contributed to their mistrust of health care clinicians and their concerns about quality care. Some parents pointed to poor communication, poorly trained interpreters, and inadequate time with staff as being due to racism. Others expressed fears of medical experimentation, medical errors, or poor quality of care occurring because of racism.

Many times, we feel alone or not listened to, like you did not exist, because of our language or our race. (Latin-American-2)

Theme #3. Respected Parental Advocacy

Parents felt that staff trusted them when staff listened to them and sought their wisdom as knowledgeable caretakers. Many parents expressed that they knew their child best, including their baseline, needs, and responses to treatments. When staff did not consider their input, parents felt disrespected, unheard, and frustrated, which contributed to conflicts.

Doctors should step back and listen to parents…I wish doctors would remember that they are not the parents. (Somali-2)

Including parents in shared decision making in both minor and major decisions engendered trust among the parents. Some parents expressed that the health care team often has an “agenda” for decision making that excluded parental preferences.

The doctors should listen to parents because the parents see the kids more than the doctors, (should) ask for parents’ thoughts using shared decision-making tools to make decisions. (Somali-5)

Parents advocated for their children’s needs in many ways, from educating the medical team to accepting or refusing recommended treatments. Parents’ ability to advocate was variable; some parents felt more empowered as they gained experience with their child, their child’s medical needs, navigating the health system, and having relationships with staff. Participants with higher education and excellent or good English skills also reported being better able to ask for help, obtain information, navigate the system, manage disagreements, and stand up for their children’s needs.

I think once you start to be okay in the situation and you start finding resources and you start to advocate, then…the staff see that… and they start to respect you in that aspect too. (Hmong-4)

Some parents expressed concern that there could be repercussions for their child’s care if they disagreed too strongly. Parents described the need to moderate their disagreement to prevent negative responses from clinicians.

Many Hmong parents are very afraid to speak up because they think ‘if I offend the doctor, the doctor will not give my child the best medicine or they will not treat her well if I upset them…’ (Hmong-5)

Parents asked for assistance, eg, social workers to deal with social-emotional needs, staff members to communicate with extended family members, patient advocates to mediate parent-staff conflicts, cultural brokers to address unmet cultural needs, and parent-support groups to learn from other parents facing similar issues.

Recommendations

Table 2 contains recommendations for individual staff members, institutions, and the health care system that addresses parents’ desires for change, related to the 3 main themes.18-26

Table 2.

Recommendations for Health Care Staff and Health Care Systems

| Themes | Parents Want To... | Recommendations for: | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health Care Staff | Health Care Systems | ||

| Informed understanding | Understand their child’s illness and medical plan Understand with quality interpretation |

For LEP Parents

|

|

| Be prepared |

|

|

|

| Have consistent team plans |

|

||

| Compassionate interactions | Feel cared about |

|

|

| Feel culturally and religiously respected |

|

||

| Feel safe, and not discriminated against |

|

||

| Respected parental advocacy | Be heard for parental wisdom |

|

|

| Be respected for authority to make decisions |

|

|

|

| Not be harmed after advocating |

|

|

|

| Have continuity in medical care |

|

|

|

| Receive support |

|

||

LEP = limited English proficiency.

DISCUSSION

This study elicited the experiences of Somali, Hmong, and Latin-American parents of children with serious illness utilizing a CBPR approach with language and culturally concordant researchers. We identified that parents’ overarching desire for health care was having 2-way trusting and respectful relationships with health care providers. Parents from all 3 ethnic communities described contributors to 2-way trust: informed understanding (being prepared), compassionate interactions (being cared for), and respected parental advocacy (being heard). Our results confirmed the challenges faced by all parents of children with serious illness within a complex health care system.27-29 Additional challenges in these 3 communities were language barriers, underlying mistrust in clinicians and the system, and historical and current experiences with racism.30

Communication and 2-Way Trust

Parents’ understanding of medical diagnoses and treatments and being prepared to take care of their children with serious illness improved trusting relationships. Consistent with prior studies on parents of children with serious illness,12 we found barriers to informed understanding including insufficient, inaccurate, and unclear information, the overuse of medical jargon, and information being given with little opportunity for questions or discussion. These barriers and their impact on 2-way trust were particularly evident among LEP participants.

Language barriers perpetuate health inequities across the spectrum of care from decreased access to services, decreased utilization of preventive care services,31 and increased risks of error, misdiagnosis, and adverse events.32,33 There is ample evidence that the use of professional interpreters improves the quality of care for LEP patients, resulting in higher patient satisfaction,34 fewer errors in communication,35 reduced disparities in utilization of services,36 and improved clinical outcomes37 when compared with nonprofessional or no interpreter. Despite these proven advantages, LEP parents in our study consistently expressed concerns that interpreters hindered 2-way trust in the health care team. While some parents preferred trusted family members as interpreters, studies have shown risks in utilizing nonprofessional interpreters, including misinterpretation and increased conflict between families and health care providers.38 High quality professional interpreters provide a necessary link to establishment of 2-way trust between health care providers and LEP families.

Compassion and 2-Way Trust

Overall, caring and compassionate interactions with the health care team facilitated 2-way trust. Attention to patients’ religious, spiritual, and cultural needs in the context of their child’s illness instilled a sense of trust from families that their child would be well cared for. On the contrary, parents’ experiences of racism in the health care system increased their distrust in individuals and the system. Parents’ social attributes, such as low socio-economic status, inadequate insurance, or LEP, may have increased their vulnerability to the power imbalance between themselves and medical staff.

Racism is a key cause of health inequities through its contribution to poor access to health care, lower quality of care, increased health risks, and poor health status for marginalized communities.39 The literature demonstrates a measurable impact of racism, such as reported by our participants, on health care delivery and health outcomes.40 These parents’ experiences with racism are consistent with studies of people from diverse backgrounds in various health care settings,41 reinforcing that interventions and policies aimed at minimizing bias and discrimination in the health care setting are crucial to health equity.

Advocacy and 2-Way Trust

Parent participants highlighted that when they were heard and they felt respected as experts, 2-way trusting respectful relationships were improved. Parents of children with chronic and serious illnesses become experts in their child’s care, as they learn and advocate for their child within the medical system,42 and continued advocacy allows parents to develop greater self-confidence as they learn new skills.43 In the existing literature as well as our study, parents report feeling unheard or being dismissed in the clinical setting44 and report a desire for staff to regard, respect, and trust them as experts.45 Parents of children with serious illness, similar to parents in our study, must balance their need and desire to advocate as experts on their child with their concern of being perceived as adversarial.45

Patient trust in health care clinicians is well researched. Characteristics of clinicians that correlate with trust include patient-centered communication, showing empathy and compassion, and providing high quality care.46 Our study adds to this knowledge base by identifying clinician trust in parents as a key contributor to parent trust in health care providers. Two-way trust could contribute to improved communication, understanding, shared decision making, and health care outcomes.46 Our study affirms that clinician behaviors that engender trust, such as active listening and questioning, collaboration, and shared decision making, is especially important for parents from ethnically diverse communities.

Interconnections

The 3 major components of 2-way trust are interconnected, with each aspect impacting the others. Studies show that clinician behaviors such as patient-centered communication, showing empathy and compassion, and providing high quality care,45,47 engender trust. Our study affirms these are important for parents from ethnically diverse communities and adds to this knowledge base by identifying clinician trust in parents as a key contributor to parent trust in health care providers. Two-way trust has been speculated to contribute to improved communication, understanding, shared decision making, and health care outcomes.48 The recommendations in Table 2 are intertwined also, so that if 1 recommendation improves an aspect of trust, it may improve other aspects of trust. For example, improving parent-child-staff continuity could improve parents’ understanding, sense of caring, and confidence in advocating, which then would improve 2-way trusting relationships. Studies have shown that patient-clinician continuity is an important contributor to trust.49

Limitations

This study had several limitations. The small sample precluded analyzing by variations in parents’ characteristics (gender, race/ethnicity, religion) and parents’ experiences based on the child’s condition (diagnoses, treatments, and length of time since diagnosis). Additionally, our conducting both focus groups and individual interviews may have influenced our data, given that people may express their experiences differently in group settings than in individual interviews. As a qualitative study in 1 metropolitan area, these results cannot be generalized to parents from all SHL communities, living in other states, and interacting in other health care systems. Nonetheless, this formative qualitative study with a purposive, criterion-based, stratified sampling included parents from diverse socioeconomic, educational, and experiential backgrounds, and yielded coherent themes from 3 diverse communities of shared desires for improved parent-staff relationships.

CONCLUSION

This study identifies recommendations to health care clinicians and institutions to improve the health care experiences for parents of children with serious illness from the SHL communities. Recommendations center on improving processes that increase informed understanding, compassionate interactions, and respect parental advocacy, which support parents’ desires for trusting and respectful 2-way relationships between parents and medical staff. Our findings highlights the potential to improve health care processes that enhance relationships, which could benefit all children. These processes should include both individual and system-level interventions driven by community voices, such as the parents in our study.

Acknowledgments

We thank the parent participants whose voices are critically important. We also acknowledge all the CAB members for their guidance, expertise, and insights into this process, including those who have granted permission to mention them by name: Carolina Gentry, Anisa Hagi-Mohamed, Mohamed Mohamed, Maria Navas, Miguel Ruiz, Dao Xiong.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

References

- 1.Hoyert DL, Mathews TJ, Menacker F, Strobino DM, Guyer B.. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2004. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):168-183. 10.1542/peds.2005-2587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang IC, Wen PS, Revicki DA, Shenkman EA.. Quality of life measurement for children with life-threatening conditions: limitations and a new framework. Child Indic Res. 2011;4(1):145-160. 10.1007/s12187-010-9079-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families . When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. National Academies Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cousino MK, Hazen RA.. Parenting stress among caregivers of children with chronic illness: a systematic review. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(8):809-828. 10.1093/jpepsy/jst049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page BF, Hinton L, Harrop E, Vincent C.. The challenges of caring for children who require complex medical care at home: ‘The go between for everyone is the parent...’. Health Expect. 2020;23(5):1144-1154. 10.1111/hex.13092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCann D, Bull R, Winzenberg T.. The daily patterns of time use for parents of children with complex needs: a systematic review. J Child Health Care. 2012; 16(1):26-52. 10.1177/1367493511420186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith J, Cheater F, Bekker H.. Parents’ experiences of living with a child with a long-term condition: a rapid structured review of the literature. Health Expect. 2015;18(4):452-474. 10.1111/hex.12040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woolf C, Muscara F, Anderson VA, McCarthy MC.. Early traumatic stress responses in parents following a serious illness in their child: a systematic review. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2016;23(1):53-66. 10.1007/s10880-015-9430-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flores G; Committee On Pediatric Research . Technical report—racial and ethnic disparities in the health and health care of children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4): e979-e1020. 10.1542/peds.2010-0188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Dyck PC, Kogan MD, McPherson MG, Weissman GR, Newacheck PW.. Prevalence and characteristics of children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(9):884-890. 10.1001/archpedi.158.9.884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinojosa MS, Knapp CA, Madden VL, Huang IC, Sloyer P, Shenkman EA.. Caring for children with life-threatening illnesses: impact on White, African American, and Latino families. J Pediatr Nurs. 2012;27(5):500-507. 10.1016/j.pedn.2011.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith J, Cheater F, Bekker H.. Parents’ experiences of living with a child with a long-term condition: a rapid structured review of the literature. Health Expect. 2015;18(4):452-474. 10.1111/hex.12040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, et al. ; IIsrael BA. Community-based participatory research: a capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094-2102. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmittdiel JA, Grumbach K, Selby JV.. System-based participatory research in health care: an approach for sustainable translational research and quality improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(3):256-259. 10.1370/afm.1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End of Life Issues; Institute of Medicine . Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. National Academies Press; 2015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK285690/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borkan JM. Immersion-Crystallization: a valuable analytic tool for healthcare research. Fam Pract. 2022;39(4):785-789. 10.1093/fampra/cmab158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson SF. A participatory group process to analyze qualitative data. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2008;2(2):161-170. 10.1353/cpr.0.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flores G, Laws MB, Mayo SJ, et al. Errors in medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences in pediatric encounters. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1): 6–14. 10.1542/peds.111.1.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S.. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):727-754. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS, Meltzer D, Shorey JM, Levinson W, Thisted RA.. Impact of interpreter services on delivery of health care to limited-English-proficient patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(7):468-474. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007468.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madrigal V, Walter JK, Sachs E, Himebauch AS, Kubis S, Feudtner C.. Pediatric continuity care intensivist: a randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2019;76:72-78. 10.1016/j.cct.2018.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edwards JD, Williams EP, McHale BL, Lucas AR, Malone CT.. Parent and provider perspectives on primary continuity intensivists and nurses for long-stay pediatric intensive care unit patients. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2023;20(2):269-278. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202205-379OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai JW, Michelson CD.. Attitudes toward implicit bias and implicit bias training among pediatric residency program directors: a national survey. J Pediatr. 2020;221:4-6. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper LA, Saha S, Van Ryn M.. Mandated implicit bias training for health professionals—a step toward equity in health care. JAMA Health Forum. 2022; 3(8):e223250. 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.3250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konrad, SC. What parents of seriously ill children value: parent-to-parent connection and mentorship. Omega (Westport). 2007;55(2):117-130. 10.2190/OM.55.2.b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lion KC, Arthur KC, García MF, et al. Pilot evaluation of the Family Bridge program: a communication- and culture-focused inpatient patient navigation program. Acad Pediatr. 2024;24(1):33-42. 10.1016/j.acap.2023.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golden SL, Nageswaran S.. Caregiver voices: coordinating care for children with complex chronic conditions. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51(8):723-729. 10.1177/0009922812445920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caicedo C. Families with special needs children: family health, functioning, and care burden. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2014;20(6):398-407. 10.1177/1078390314561326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eneriz-Wiemer M, Sanders LM, Barr DA, Mendoza FS.. Parental limited English proficiency and health outcomes for children with special health care needs: a systematic review. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(2):128-136. 10.1016/j.acap.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laster M, Kozman D, Norris KC.. Addressing structural racism in pediatric clinical practice. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2023;70(4):725-743. 10.1016/j.pcl.2023.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai J, Shi L, Yu WL, Lebrun LA.. Usual source of care and the quality of medical care experiences: a cross-sectional survey of patients from a Taiwanese community. Med Care. 2010;48(7):628-634. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181dbdf76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu T, Myerson R.. Disparities in health insurance coverage and access to care by English language proficiency in the USA, 2006–2016. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1490-1497. 10.1007/s11606-019-05609-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yeheskel A, Rawal S.. Exploring the ‘patient experience’ of individuals with limited English proficiency: a scoping review. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019; 21(4):853-878. 10.1007/s10903-018-0816-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boylen S, Cherian S, Gill FJ, Leslie GD, Wilson S.. Impact of professional interpreters on outcomes for hospitalized children from migrant and refugee families with limited English proficiency: a systematic review. JBI Evid Synth. 2020; 18(7):1360-1388. 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flores G, Laws MB, Mayo SJ, et al. Errors in medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences in pediatric encounters. Pediatrics. 2003; 111(1):6-14. 10.1542/peds.111.1.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S.. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):727-754. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kai J, Beavan J, Faull C.. Challenges of mediated communication, disclosure and patient autonomy in cross-cultural cancer care. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(7): 918-924. 10.1038/bjc.2011.318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT.. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson TJ. Racial bias and its impact on children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2020;67(2):425-436. 10.1016/j.pcl.2019.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamed S, Bradby H, Ahlberg BM, Thapar-Björkert S.. Racism in healthcare: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):988. 10.1186/s12889-022-13122-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bogetz JF, Trowbridge A, Lewis H, et al. Parents are the experts: a qualitative study of the experiences of parents of children with severe neurological impairment during decision-making. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62(6): 1117-1125. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang M, Mannan H, Poston D, Turnbull AP, Summers JA.. Parents’ perceptions of advocacy activities and their impact on family quality of life. Res Pract Persons Severe Disabil. 2004;29(2):144-155. 10.2511/rpsd.29.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hong H, Oh HJ.. The effects of patient-centered communication: exploring the mediating role of trust in healthcare providers. Health Commun. 2020;35(4): 502-511. 10.1080/10410236.2019.1570427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brady PW, Giambra BK, Sherman SN, et al. The parent role in advocating for a deteriorating child: a qualitative study. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10(9):728-742. 10.1542/hpeds.2020-0065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rolfe A, Cash-Gibson L, Car J, Sheikh A, McKinstry B.. Interventions for improving patients’ trust in doctors and groups of doctors. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;(3):CD004134. 10.1002/14651858.CD004134.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williamson LD, Thompson KM, Ledford CJW.. Trust takes two…. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022;35(6):1179-1182. 10.3122/jabfm.2022.220126R1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thornton RL, Glover CM, Cené CW, Glik DC, Henderson JA, Williams DR.. Evaluating strategies for reducing health disparities by addressing the social determinants of health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(8):1416-1423. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee TH, McGlynn EA, Safran DG.. A framework for increasing trust between patients and the organizations that care for them. JAMA. 2019;321(6):539-540. 10.1001/jama.2018.19186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mainous AG III, Baker R, Love MM, Gray DP, Gill JM.. Continuity of care and trust in one’s physician: evidence from primary care in the United States and the United Kingdom. Fam Med. 2001;33(1):22-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]