Doctors often consider anxiety to be a normal response to physical illness. Yet, anxiety afflicts only a minority of patients and tends not to be prolonged. Any severe or persistent anxious response to physical illness merits further assessment.

What is anxiety?

Anxiety is a universal and generally adaptive response to a threat, but in certain circumstances it can become maladaptive. Characteristics that distinguish abnormal from adaptive anxiety include

Somatic and psychological symptoms of anxiety disorders

In all anxiety disorders

| • Palpitations, pounding heart, accelerated heart rate | • Sweating |

| • Trembling or shaking | • Dry mouth |

| • Difficulty in breathing | • Feeling of choking |

| • Chest pain or discomfort | • Nausea or abdominal discomfort |

| • Feeling dizzy, unsteady, faint, light headed | • Feeling that objects are unreal or that self is distant |

| • Fear of losing control, going crazy, passing out | • Fear of dying |

| • Numbness or tingling sensations | |

| • Hot flushes or cold chills | |

In more severe or generalised anxiety disorders

| • Muscle tension or aches and pains | • Restlessness, inability to relax |

| • Feeling keyed up, on edge, or mentally tense | • Sensation of difficulty swallowing, lump in the throat |

| • Exaggerated response to minor surprises or being startled | • Difficulty concentrating or “mind going blank” from anxiety or worry |

| • Persistent irritability | • Difficulty in getting to sleep because of worry |

Anxiety out of proportion to the level of threat

Persistence or deterioration without intervention (>3 weeks)

Symptoms that are unacceptable regardless of the level of threat, includingRecurrent panic attacks Severe physical symptomsAbnormal beliefs such as thoughts of sudden death

Disruption of usual or desirable functioning.

Unfortunately, there are few studies of the natural course of anxiety in physically ill patients, so it can be difficult to judge the distinction between normal and abnormal anxiety. In particular, some of the criteria used can be difficult to apply when a patient is experiencing a real threat of disease. A more reliable basis for diagnosing morbid anxiety is often that it causes unacceptable and disruptive problems in its own right.

Distinguishing features of anxiety disorders

Anxious adjustment disorder

Prevalence in general population—Not known

Cardinal features

Onset of symptoms within 1 month of an identifiable stressor

No specific situation or response

Generalised anxiety disorder

Prevalence in general population—31 cases/1000 adults

Cardinal features

Period of 6 months with prominent tension, worry, and feelings of apprehension about everyday problems

Present in most situations and no specific response

Panic disorder

Prevalence in general population—8 cases/1000 adults

Cardinal features

Discrete episode of intense fear or discomfort with crescendo pattern; starts abruptly and reaches a maximum in a few minutes

Occurs in many situations, with a hurried exit the typical response

Phobia

Prevalence in general population—11 cases/1000 adults

Cardinal features

No specific symptom pattern

Occurs in specific situations, with an avoidance response

Abnormal anxiety can present with various typical symptoms and signs, which include

Autonomic overactivity

Behaviours such as restlessness and reassurance seeking

Changes in thinking, including intrusive catastrophic thoughts, worry, and poor concentration

Physical symptoms such as muscle tension or fatigue.

Classification of abnormal anxiety

Abnormal anxiety can be classified according to its clinical features. In standardised diagnostic systems there are four main patterns of abnormal anxiety.

Anxious adjustment disorder—Anxiety is closely linked in time to the onset of a stressor.

Generalised anxiety disorder—Anxiety is more pervasive and persistent, occurring in many different settings.

Panic disorder—Anxiety comes in waves or attacks and is often associated with panicky thoughts (catastrophic thoughts) of impending disaster and can lead to repeated emergency medical presentations.

Phobic anxiety—Anxiety is provoked by exposure to a specific feared object or situation. Medically related phobic stimuli include blood, hospitals, needles, doctors and (especially) dentists, and painful or unpleasant procedures.

Additionally, anxiety often presents in association with depression. Mixed anxiety and depressive disorders are much more common than anxiety disorders alone. Treatment for the depression may resolve the anxiety. Anxiety can also be the presenting feature of other psychiatric illnesses common in physically ill people, such as delirium or drug and alcohol misuse.

Detecting anxiety and panic

Who is at risk?—Certain groups are more vulnerable to anxiety disorders: younger people, women, those with social problems, and those with previous psychiatric problems. However, such associations are less consistent in the setting of life threatening illness, perhaps because susceptibility to anxiety becomes less important as the stressor becomes more severe. Pathological anxiety is commoner among patients with a chronic medical condition than in those without.

Medical conditions mimicking or directly resulting in anxiety

| • Poor pain control—Such as ischaemic heart disease, malignant infiltration | • Anaemia |

| • Hypoxia—May be episodic in both asthma and pulmonary embolus | • Hypoglycaemia |

| • Hypocapnia—May be due to occult bronchial hyperreactivity | • Hyperkalaemia |

| • Central nervous system disorders (structural or epileptic) | • Alcohol or drug withdrawal |

| • Vertigo | |

| • Thyrotoxicosis | |

| • Hypercapnia | |

| • Hyponatraemia | |

Excluding physical causes—There are many presentations with physical complaints whose aetiology may be due to anxiety. Equally, several physical illnesses can cause anxiety or similar symptoms. When such disorders cannot be reliably distinguished from anxiety by clinical examination they need to be excluded through appropriate investigation. A firm diagnosis of anxiety should therefore be made only when a positive diagnosis can be supported by the presence of a typical syndrome and after appropriate investigation.

Use of screening questionnaires—Screening, with self completed questionnaires, has been widely used to improve detection of psychiatric morbidity, including anxiety. Such questionnaires are acceptable to patients and can be amenable to computerised automation in the clinic. The hospital anxiety and depression scale, the general health questionnaire, and many quality of life instruments include anxiety items. No one questionnaire has been consistently shown to be preferable to another.

Self reported questionnaires used to assess anxiety

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

Advantages

Excludes somatic symptoms of disease

Brevity (14 items in all, 7 concerning anxiety)

Widespread use in cancer and other physical illnesses

More effective than many other instruments

Used as a screen and a measure of progress

Disadvantages

Recent concern that, used alone, it is poor at detecting depression

State-trait anxiety inventory

Advantages

Specific to anxiety

Used as a screen and a measure of progress

Disadvantages

Used alone does not detect depression

Longer (20-40 items) than many other self reported questionnaires

General health questionnaire

Advantages

Brevity (12 or 28 items)

Excludes somatic symptoms of disease

Used as a screen and a measure of progress

Disadvantages

May not be accurate in detecting chronic problems

Iatrogenic anxiety—Anxiety symptoms can be caused by poor communication (see first two articles in this series) and by prescribed drugs. Well known causes include corticosteroids, β adrenoceptor agonists, and metoclopramide, but doctors should remember that many less commonly used drugs can cause psychiatric syndromes.

Common drug causes of anxiety

| • Anticonvulsants—Carbamazepine, ethosuximide | • Antidepressants—Specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| • Antimicrobials—Cephalosporins, ofloxacin, aciclovir, isoniazid | • Antihistamines |

| • Bronchodilators—Theophyllines, β2 agonists | • Calcium channel blockers—Felodipine |

| • Digitalis—At toxic levels | • Dopamine |

| • Oestrogen | • Inotropes—Adrenaline, noradrenaline |

| • Insulin—When hypoglycaemic | • Levodopa |

| • Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs—Indomethacin | • Corticosteroids |

| • Thyroxine | |

Many drugs can cause palpitation or tremor, but these should be easily distinguished from anxiety by clinical examination

Treatment of anxiety and panic

Role of non-specialists

Treating anxiety is part of the management of most medical conditions. It can lead to direct improvement of symptoms or improve patient compliance. It is important to intervene if a positive diagnosis of anxiety is made. Without treatment, anxiety is associated with increased disability, increased use of health service resources, and impaired quality of life.

Involving a mental health professional is not always possible for anxious patients, particularly those in general hospital settings. The range of available services is often limited, and not all patients are prepared to accept referral. Since many patients have to be managed without recourse to psychiatric services, treating anxiety should be considered a core skill for all doctors.

Giving information is often the first step in helping anxious patients, so much so that it has been said that knowledge is reassurance. While information must be tailored to the wishes of the individual, many patients want more information than they are given. Such a simple step as showing people where they are to be cared for can reduce anxiety.

Effective communication is central to information giving, with evidence that anxiety is associated with poor communication. Training doctors to use open questions, discuss psychological issues, and summarise—and to avoid reassurance, “advice mode,” and leading questions—has been shown to lead to greater disclosure and enduring change in patients with psychological problems.

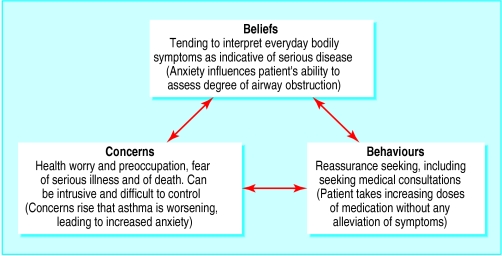

Reassurance is one of the most widely practised clinical skills. Doctors often need to tell patients that their symptoms are not due to occult disease. Simple reassurance, however, may be ineffective for anxious patients; their anxiety may be reduced initially by the consultation, but it rapidly returns. Several theoretical models of this problem have been suggested, based on the patterns of thinking (“cognitions”) of people who are difficult to reassure.

Drug interventions in anxious medical patients

β Blockers

Benefits unproved in randomised controlled trials

Help to control palpitation and tremor, but not anxiety itself

Often used for performance anxiety, such as in interviews or examinations

Tricyclic antidepressants (such as imipramine)

Likely to be beneficial (number needed to treat=3)

Anxiolytic effect is slow in onset (weeks)

Not dependency inducing

Useful in panic disorder or in anxiety with depression

Anticholinergic effects can be ameliorated by a low starting dose

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (such as paroxetine)

Benefit unproved but suggested

Less anticholinergic effects than tricyclic antidepressants

Start at low dose in anxious patients

Short acting benzodiazepines (such as alprazolam)

Effectiveness and relative lack of toxicity well established

All benzodiazepines can induce dependency and should be used only when an identified stressor will end after a short period (days)

Rapid onset of effect, but problems may recur on withdrawal

Less likely to accumulate in liver

Antipsychotics (such as haloperidol)

Benefits unproved in randomised controlled trials

Useful adjunct to benzodiazepines

Less respiratory depression that benzodiazepines, particularly for haloperidol

Not dependency inducing

Risk of acute dystonia, akathisia, and parkinsonism

Avoid long term use because of risk of tardive dyskinesia

Buspirone

Limited evidence for effectiveness from randomised controlled trials, few clinicians are convinced

Causes some nausea and dizziness

Preparation for unpleasant procedures can remove the additional burden of facing the unknown. It may also allow planning of short term tactics for dealing with anxiety provoking circumstances. Anxious patients are highly vigilant and overaware of threatening stimuli. They often use “quick fix” techniques based on avoidance of threat to reduce anxiety; such strategies are generally maladaptive and result in increasing disability. In some medical situations, however, such avoidance may not be a bad thing if the threat is temporary. A similar effect is seen with use of benzodiazepine to provide temporary relief from anxiety symptoms that will not recur because the stressor is not persistent.

Behavioural treatments are among the most effective treatments for anxiety disorders. Many patients restrict their activities in response to anxiety, which often has the effect of increasing both the level of anxiety and the degree of disability in the longer term. The principle of treatment is that controlled exposure to the anxiety producing stimulus will eventually lead to diminution in symptoms. Although specific behavioural treatments will normally be conducted by specialists, other clinicians should be aware of the basic principles. It is important to encourage and help patients to maintain their normal activities as much as possible, even if this causes temporary increases in anxiety.

Drug treatments—Several drugs can be used to treat anxiety, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. Long term benzodiazepine dependence and misuse are considered by many to be a problem in medical practice. Although the evidence for this is conflicting, the use of benzodiazepines may be reserved for the short term treatment of anxiety and for emergencies.

Drug withdrawal—Dependence on other substances, particularly analgesics and alcohol, occurs fairly frequently in the context of anxiety. This often results from self medication for anxiety. In this situation withdrawal from the existing “treatment” will be an important part of the anxiety management programme.

Role of specialist treatment in brief psychological therapies

Clinical studies indicate that psychological interventions for anxiety can be effective both in general psychiatric settings and for physically ill patients. The most popular, and those with the best evidence to support them, are based on the principles of behaviour, cognitive behaviour, or interpersonal therapy.

Further reading

Noyes R, Hoehn-Saric R. Anxiety in the medically ill: disorders due to medical conditions and substances. In: Noyes R, Hoehn-Saric R, eds. The anxiety disorders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998:285-334

Colon EA, Popkin MK. Anxiety and panic. In: Rundell JR, Wise MG, eds. Textbook of consultation-liaison psychiatry. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1996:403-25

Westra HA, Stewart SH. Cognitive behavioural therapy and pharmacotherapy: complementary or contradictory approaches to the treatment of anxiety?

Cochrane Depression Anxiety and Neurosis Group. See list of reviews at www.update-software.com/abstracts/g240index.htm

In behaviour and cognitive behaviour therapies the main aim is to help patients identify and challenge unhelpful ways of thinking about and coping with physical symptoms and their meaning, about themselves, and about how they should live their lives. In interpersonal therapies the main focus is on relationships with family members and friends—how such relationships are affected by illness and how they influence patients' current emotional state. Patients need to know that such therapies may be both brief and practical. Fewer than six sessions may be enough, concentrating on symptoms or the immediate problems associated with them and learning new ways of dealing with problems. In only a minority of cases is more extended therapy needed, usually when anxiety is longer standing and only partially due to associated physical disease.

Figure.

William Cullen (1710-90) coined the term neurosis (though the term as he used it bears little resemblance to modern concepts of anxiety disorders)

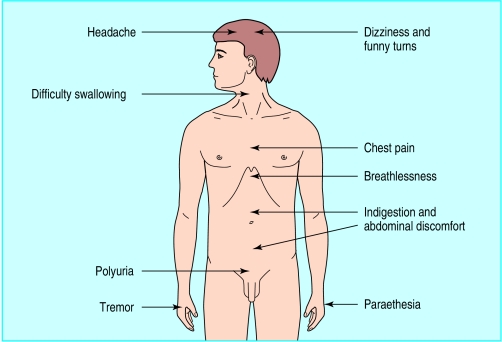

Figure.

Common physical problems that may be caused by anxiety

Figure.

Characteristic features of health anxiety (using the example of asthma)

Footnotes

Allan House is professor of liaison psychiatry at the Academic Unit of Psychiatry and Behavioural Sciences, School of Medicine, University of Leeds. Dan Stark is specialist registrar in medical oncology at the Academic Unit of Oncology, St James's University Hospital, Leeds

The ABC of psychological medicine is edited by Richard Mayou, professor of psychiatry, University of Oxford; Michael Sharpe, reader in psychological medicine, University of Edinburgh; and Alan Carson, consultant neuropsychiatrist, NHS Lothian, and honorary senior lecturer, University of Edinburgh. The series will be published as a book in winter 2002.