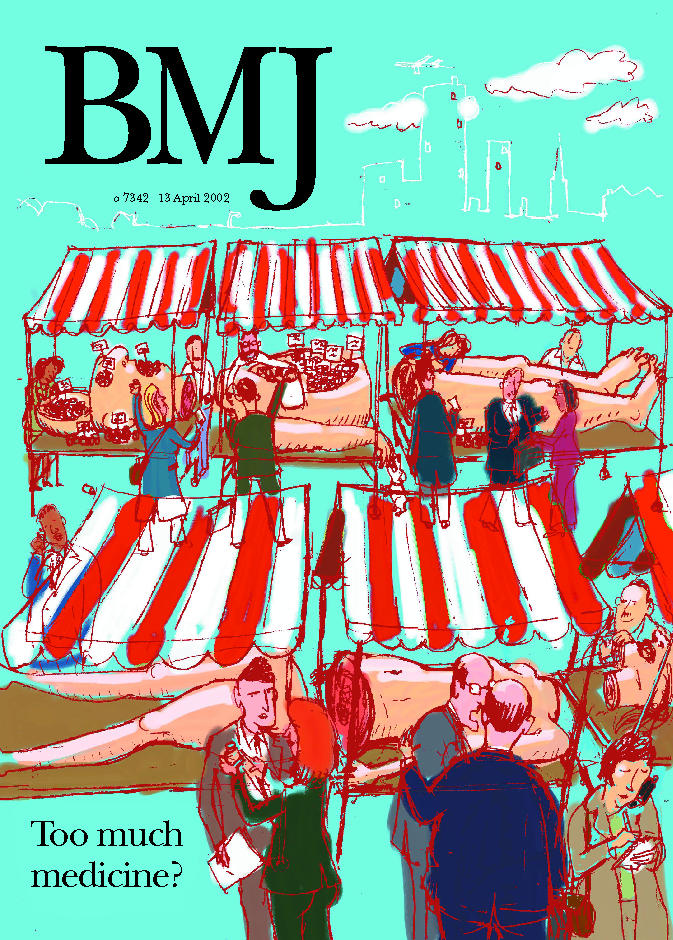

Editor—It is true that the pharmaceutical industry, with others, is involved in sponsoring the definition of diseases, as suggested by Moynihan et al.1 Both the pharmaceutical industry and regulatory authorities that license new medicines need to develop closely defined definitions so that the safety and efficacy of new medicines can be properly measured.

More medicalisation is in fact needed, as indicated by Ebrahim and Bonaccorso and Sturchio.2,3 The rise of guideline led care around the Western world shows that far too many serious diseases are underdiagnosed and undertreated. Failure to put evidence based medicine into practice is quite legitimately addressed by the pharmaceutical industry. Examples include the underuse of statins in the United Kingdom, the delay in the uptake of thrombolysis during the 1980s, and reliance on old psychotropic drugs when newer agents have a much more favourable profile of side effects.

Of course, disease awareness campaigns are likely to expand the market for drugs for a given disease, but the market will expand for competitors' products as well as those of the sponsoring company. However, the real value of disease awareness campaigns is exactly what it says: making consumers aware that treatment may be available for their condition. Not infrequently, major disease is detected as a result of a patient seeking medical advice after contact with a disease awareness campaign.

Moynihan et al imply that preventive medicine is threatening the viability of publicly funded healthcare systems. Yet clearly, it is far better to prevent disease than to treat it when it is established. The benefits of stopping smoking, treating hypertension, reducing raised blood lipid concentrations, etc, are all well established but could not be done without the help of the pharmaceutical industry.

In choosing the diseases that Moynihan et al detail as sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry, it is unfortunate that the Australian experience has been highlighted. In Europe patients cannot be targeted with promotional material and such material for health professionals in the United Kingdom has to comply with the code of practice of the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. Moynihan et al imply that osteoporosis has been effectively sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry. However, far too many people who fall and develop a fracture are not considered for treatment of osteoporosis.

In conclusion, the pharmaceutical industry is not inventing disease but rather working hard to develop new, innovative drugs for the overall benefit of humankind.

References

- 1.Moynihan R, Heath I, Henry D. Selling sickness: the pharmaceutical industry and disease mongering [with commentary by P C Gøtzsche] BMJ. 2002;324:886–891. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.886. . (13 April.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebrahim S. The medicalisation of old age. BMJ. 2002;324:861–863. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.861. . (13 April.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonaccorso SN, Sturchio JL. Direct to consumer advertising is medicalising normal human experience: against. BMJ. 2002;324:910–911. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.910. . (13 April.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]