Abstract

目的

探讨高流量鼻导管(HFNC)吸氧在妊娠合并心脏病患者剖宫产中的应用。

方法

本研究为单中心、单盲、随机临床试验。拟行剖宫产的妊娠合并心脏病患者被随机分为2组:HFNC组接受HFNC疗法(n=27,吸气流量30 L/min,氧浓度40%),传统吸氧(COT)组接受传统氧疗(n=31,通过鼻导管输送,氧流量5L/min)。主要观察指标为母体血氧饱和度下降(SpO2<94%,持续3 min以上,或PaO2/FIO2≤300 mmHg)。母体及新生儿不良事件数据分析中,对于近似高斯分布的连续变量,使用Student的t检验;对于倾斜分布的变量,进行Wilcoxon秩和检验。分类变量采用Fisher的确切检验或卡方检验。

结果

HFNC组中有7.4% 的孕妇(n=2/27)出现母体血氧饱和度下降,而COT组中有32.3%的孕妇(n=10/31)出现。在围手术期间,没有任何病例需要气管插管。HFNC组在术后白细胞增多的发生率较高(P<0.05),但没有母体发热及其他与炎症相关的症状。在母体次要结局指标(呼吸支持需求、母体重症监护室入住时间、术后呼吸系统并发症和心血管系统并发症)以及新生儿结局方面,两组之间无显著差异(P>0.05)。

结论

HFNC疗法显著降低了妊娠合并心脏病患者围手术期母体血氧饱和度下降的发生率,并且对母体或胎儿的短期临床结果没有不良影响。

Keywords: 传统氧疗, 高流量鼻导管吸氧, 母体血氧饱和度下降, 术后白细胞增高, 妊娠合并心脏病

Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the beneficial effects of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy during cesarean section in pregnant women with heart disease.

Methods

We conducted a single-center, single-blinded randomized trial of HFNC oxygen therapy in pregnant women with heart disease undergoing cesarean section under neuraxial anesthesia. The participants were randomly assigned to receive either HFNC oxygen therapy with inspiratory flow of 30 L/min with 40% FIO2 (n=27) or conventional oxygen therapy (COT) with oxygen flow rate of 5 L/min via a nasal cannula (n=31). The primary outcome was maternal desaturation (SpO2<94% lasting more than 3 min or PaO2/FIO2≤300 mmHg).

Results

Maternal desaturation was observed in 7.4% (2/27) of the women in HFNC group and in 32.3% (10/31) in the COT group. None of the cases required tracheal intubation during the perioperative period. The HFNC group had a significantly higher incidence of postoperative leukocytosis (P<0.05) but without pyrexia or other inflammation-related symptoms. There were no significant differences between the two groups in the secondary maternal outcomes (need for respiratory support, maternal ICU admission, postoperative respiratory complications, and cardiovascular complications) or neonatal outcomes (P>0.05).

Conclusion

In pregnant women with heart disease, HFNC therapy can significantly reduce the rate of maternal desaturation during the perioperative period of cesarean section without adverse effects on short-term maternal or fetal outcomes.

Keywords: conventional oxygen therapy, high flow nasal cannula, maternal desaturation, postoperative leukocytosis, pregnancy with heart disease

在许多国家,妊娠期心血管疾病的患病率逐渐上升,成为产妇死亡的主要原因之一[1, 2]。对于麻醉医生来说,处理合并心脏病的围产期患者是一项具有挑战性的任务,因为它涉及到复杂的气道管理和波动的母体血流动力学[3]。此外,采用不同的麻醉管理策略可能会对胎儿产生相关的不良影响[4]。值得注意的是,不同程度的母体缺氧会对母体心血管系统,以及胎盘胎儿等产生相应的不良事件[5, 6]。目前,针对高危妊娠的安全氧疗缺乏相应的指南及循证医学支持。因此,应更加重视对进行剖宫产的妊娠合并心脏病患者的管理。

既往对于合并心脏病的患者进行剖宫产常常选择气管插管全身麻醉。然而,过去几年中,越来越多的妊娠合并心脏病患者选择椎管内麻醉。研究发现[7-9],合并心脏病的孕妇进行剖宫产时,全身麻醉可导致更高的母体不良事件发生率。相反,椎管内麻醉导致心血管不良事件的发生率较低[10],并且与术后呼吸不良事件发生率呈负相关[11]。此外,妊娠期解剖及生理结构的变化增加了困难气道管理的风险。研究指出妊娠合并呼吸衰竭的风险约1/500,尤其多见于合并心脏病的女性[12]。因此,有必要确定一种最佳的氧疗方法,既能最小化气管插管的需求,又能确保在剖宫产围手术期间母婴的安全。

高流量鼻导管吸氧(HFNC)是一种新型的呼吸支持技术。它通过鼻导管提供高流量、加热和湿化的可控氧浓度[13]。目前HFNC在各种临床适应症中的使用逐渐增多。最近的研究表明,HFNC氧疗[14-16]与较低的气管插管发生率,减少患者对呼吸机的依赖以及较低的死亡率密切相关。尽管HFNC氧疗在产妇中的应用逐渐增多[17-20],但其在合并心脏病的孕妇进行剖宫产时的疗效和安全性仍然缺乏证据。因此,我们进行了一项随机对照试验,研究HFNC氧疗对妊娠合并心脏病患者母婴的相关事件。

1. 资料和方法

1.1. 研究设计

本研究获得广东省人民医院伦理委员会的伦理批准[伦理批号:GDREC2017367H(R1);中国临床试验注册:ChiCTR1800019788]。所有方法均按照相关的指南和法规进行。研究中的每位参与者都签署了知情同意书。纳入标准:年龄在18岁及以上、患有母体心脏病的孕妇,准备接受椎管内麻醉下的剖宫产手术。排除标准:多胎妊娠、存在鼻腔气道阻塞或已知气道病理、选择全身麻醉、BMI≥40 kg/m2、怀疑胎儿患有先天性心脏病、术前SpO2<94%以及拒绝参与研究。

1.2. 分组信息

在HFNC组(Optiflow)中,氧气以30 L/min的流速、37 ℃的温度、40% 的FIO2浓度进行输送。在COT组中,采用鼻导管以5 L/min的流速进行氧气供应,氧浓度估算方法采用以下Shapiro公式[21]:每分钟的氧流量×0.04+0.20。

使用Microsoft Excel 2013生成了一个1∶1分配给HFNC组或COT组的随机序列,将该序列放入密封信封中,并在参与者入组之前对其保密。由于干预的性质和研究方法的原因,本临床试验采用单盲实验方法。

1.3. 手术和监测

在手术前,妊娠合并心脏病的患者在病房里均接受了低流量鼻导管氧疗。送达手术室后,每个患者均实施标准监测,并在局麻下在桡动脉置入一根20 G的动脉导管并进行有创监测血压。待所有监测建立后,立即给患者根据随机分组使用不同氧疗方式。在实施椎管内麻醉前,给予胶体液300~500 mL。在严格无菌条件下,产妇为侧卧位,通过中线技术在L2~3或L3~4的间隙处实施腰硬联合麻醉(CSEA)。麻醉完成后,产妇维持于左侧倾斜15°仰卧位。在麻醉完成10 min后进行针刺试验以确定麻醉平面。当平面达到T6时,开始剖宫产。当平面低于T6时,通过硬膜外导管给予2%利多卡因(上海朝晖,10 mL:200 mg)以进行调整。如果切皮时患者仍有疼痛感,静脉注射舒芬太尼(5 µg,宜昌人福,1 mL:50 μg)。出院后,通过电话调查的方式对受试者进行了产后42 d以及6个月的随访。通过询问获取了母婴健康状况的评估、再入院和门诊就诊等信息。

1.4. 数据收集

本研究收集了患者基础信息以及相关的临床数据。在入室时、CSEA后10 min、剖宫产开始时、胎儿分娩时以及手术结束时均记录了生理变量,包括有创动脉血压、呼吸频率、心率和外周血氧饱和度(SpO2)。记录了母体住院时间和不良事件,包括低血压、心律失常、恶心、呕吐、寒战以及其他特定的辅助治疗,如利尿剂和苯肾上腺素。在3个时间点分别采集母体动脉血气:⑴入室建立动脉导管时;⑵胎儿分娩时(可以更好地反映椎管内麻醉对母体的影响);⑶手术结束时(相对稳定的血流动力学状态)。在胎儿娩出时,收集了胎儿脐静脉(UV)血液进行血气测量。所有进行血液分析的研究人员不知道患者的分组情况,并且未参与患者护理。

围手术期母体血氧饱和度下降定义为SpO2<94%,持续时间超过3 min,或PaO2/FIO2≤300 mmHg。对于SpO2<94%,持续时间超过3 min,或者SpO2<90%,并且通过应用较高的FIO2来恢复血氧饱和度读数至≥94%的患者,记录该患者数据,但此动脉血气及后续指标不用于该研究的分析。低血压定义为平均动脉压(MAP)在1 min以上低于65 mmHg。母体低血压发生时,给予苯肾上腺素(50 µg)的静脉注射,直至MAP≥65 mmHg。研究还记录了术中需要治疗的心律失常事件。术后呼吸并发症定义为急性呼吸衰竭、肺炎和肺不张。母体心血管并发症包括心力衰竭、静脉血栓栓塞事件、严重心律失常、高血压急症和肺动脉高压危象。

1.5. 主要终点

主要观察指标是母体血氧饱和度下降(SpO2<94%,持续时间超过3 min或PaO2/FIO2≤300 mmHg)。母体次要结果包括呼吸支持、呼吸频率、其他生理变量(动脉血压和心率)、受试者舒适度、不良事件和ICU时间等。新生儿结果由一位对该研究保密的儿科医生评估。在胎儿娩出后,记录新生儿体质量、1 min和5 min的Apgar评分、脐静脉血气分析、新生儿复苏措施等。所有新生儿在出生后24 h内进行了随访,并记录了不良事件。

1.6. 统计学分析

样本量的计算基于手术结束时母体PaO2/FIO2≤300 mmHg。我们的前期实验结果显示HFNC组和COT组的发生率分别为8%和39%。按照80%的功效和双侧显著性水平0.05检测差异,估计每组需要27名受试者。考虑到可能的10%~15%的随访丧失,计划在研究中每组招募30~32例患者。

所有统计分析均使用Stata(版本15.1)进行。比较HFNC组和COT组的基础数据和相关的结果。近似高斯分布的连续变量以均数±标准差表示,而倾斜分布的连续变量表示为中位数和四分位数范围。分类变量以频数和百分比表示。对于近似高斯分布的连续变量,使用Student的t检验;对于倾斜分布的变量,进行Wilcoxon秩和检验。分类变量采用Fisher的确切检验或卡方检验。所有P值均为双侧,显著性水平为0.05。

2. 结果

2.1. 实验流程图和患者基线特征

研究持续时间为2018年12月~2019年12月,随访结束于2020年6月。共有66例受试者受邀参与试验,其中58例完成了试验(图1)。两组患者均患有器质性心脏病,其心脏病类型之间没有统计学意义上的差异。

图1.

临床试验流程图

Fig.1 Flow diagram of patient recruitment.

两组的母体基线特征,包括术前用药和实验室检验指标等数据,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05,表1)。所有受试者在手术中的相关数据之间差异没有统计学意义(P>0.05,表2)。其中,HFNC组有1例患者,在手术前血红蛋白水平为7.7 g/dL,在手术期间输注了两个单位的红细胞。

表1.

患者术前临床基本资料

Tab.1 Baseline maternal characteristics

| Characteristic | COT (n=31) | HFNC (n=27) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 29.0±0.9 | 30.4±1.1 | 0.28 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.7±0.4 | 25.7±0.8 | 0.29 |

| Gestational age(weeks) | 36.7±2.2 | 35.8±3.0 | 0.18 |

| Primigravida | 14 (45.2%) | 10 (37%) | 0.53 |

| Primiparity | 22 (71%) | 17 (63%) | 0.52 |

| NYHA functional classification | 0.33 | ||

| I | 26 (83.9%) | 18 (66.7%) | |

| II | 1 (3.2%) | 1 (3.7%) | |

| III | 4 (12.9%) | 6 (22.2%) | |

| IV | 0 (0) | 2 (7.4%) | |

| mWHO classification | 0.82 | ||

| Missing# | 1 (3.2%) | 2 (7.4%) | |

| I | 7 (22.6%) | 4 (14.8%) | |

| II | 3 (9.7%) | 2 (7.4%) | |

| II-III | 5 (16.1%) | 4 (14.8%) | |

| III | 8 (25.8%) | 5 (18.5%) | |

| IV | 7 (22.6%) | 10 (37%) | |

| Hemoglobin (115-150 g/L) | 0.19 | ||

| Low | 15 (48.4%) | 18 (66.7%) | |

| Normal | 16 (51.6%) | 9 (33.3%) | |

| High | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Emergent CS | 11 (35.5%) | 8 (29.6%) | 0.64 |

| Maternal hypertension | 2 (6.5%) | 3 (11.1%) | 0.66 |

| Maternal gestational diabetes mellitus | 4 (12.9%) | 5 (18.5%) | 0.72 |

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 108.4±1.9 | 111.6±3.0 | 0.36 |

| Diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 68.4±1.6 | 66.1±2.3 | 0.42 |

| Heart rate (beat/min) | 81.5±2.4 | 85.4±2.5 | 0.28 |

| SpO2 (%) | 98.4±0.2 | 98.1±0.4 | 0.47 |

| Oxygen flow rate (L/min) ## | 0.64 | ||

| 3 | 29 (93.5%) | 25 (92.6%) | |

| 4 | 2 (6.5%) | 2 (7.4%) |

Data are presented as Mean±SD or number of cases with percentages [n (%)]. #Heart diseases of missing mWHO classification include aortic right coronary sinus aneurysm, left atrial myxoma, and small coronary-pulmonary artery fistula. ##Oxygen therapy through nasal catheter at least 24 h before cesarean section in the ward.

表2.

患者术中各项临床指标

Tab.2 Intraoperative clinical and parturition conditions of the mothers who gave birth under neuraxial anesthesia

| Outcomes | COT (n=31) | HFNC (n=27) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of block (Above T6) | 2 (6.5%) | 0(0) | 0.37 |

| Volume of local anesthetics (0.5% Bupivacaine, mL) | 1.84±0.03 | 1.89±0.03 | 0.23 |

| Intravenous opioid adjuvant | 2 (6.5%) | 1 (3.7%) | 1.00 |

| Arrhythmia | 18 (58.1%) | 16 (59.3%) | 0.57 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 3 (9.7%) | 0 (0) | 0.24 |

| Shivering | 1 (3.2%) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Treatment of hypotension | 9 (29%) | 9 (33.3%) | 0.78 |

| Furosemide | 0 (0) | 3 (11.1%) | 0.10 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 240.3±45.2 | 247±77.1 | 0.68 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 69.8±16.3 | 70.3±19.8 | 0.91 |

| Reduced respiratory rate# | 15 (48.4%) | 16 (59.3%) | 0.41 |

| SpO2≤94%## | 2 (6.5%) | 0 (0) | 0.49 |

| Oxygen partial pressure increase(T2-T1, mmHg)### | 51.5±37.9 | 83.7±41.7 | <0.01 |

| Oxygen partial pressure increase(T3-T1, mmHg)### | 47.9±48.1 | 88.5±40.7 | <0.01 |

| Maternal desaturation (PaO2:FIO2, T2) ### | 5 (16.1%) | 1 (3.7%) | 0.20 |

| Maternal desaturation (PaO2:FIO2,T3) ### | 10(32.3%) | 2(7.4%) | 0.02 |

Data are presented as Mean±SD or number of cases with percentages [n(%)]. #Respiratory rate at the end of the operation was compared with the baseline value. ##SpO2 levels rising to more than 94% within 3 min. The PaO2/FIO2 at T2 and T3 were 382.5 mmHg and 332.5 mmHg in one patient, and were 186.23 mmHg and 204.25 mmHg in the others, respectively. ###Maternal arterial blood gas analysis was done at T1 (baseline), T2 (at delivery of the fetus) and T3 (at the end of the operation).

2.2. HFNC组与COT组对妊娠合并心脏病母体术中氧合指标的影响

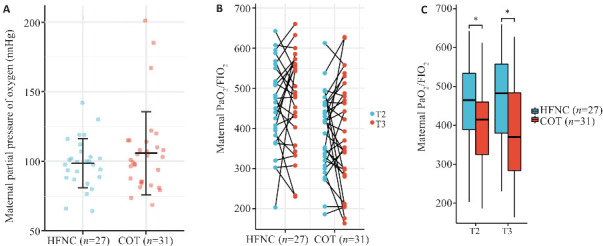

在手术结束时,母体血氧饱和度下降发生率存在显著差异(图2,P<0.05)。但是母体次要结局指标之间没有显著的统计学差异。在 COT组中,有2例患者出现PaO2/FIO2<200 mmHg:其中1例患者在手术后发生心力衰竭(T3时间点的动脉血氧饱和度为SaO2 93.7%),另1例患者需要使用血管活性药物来维持围手术期的血压(SaO292.2%)。两组中母体的动脉血气分析结果(pH,pCO2和Lac)呈现出相似的趋势(图3)。在COT组的基线中,有3例患者的PaO2>200 mmHg,其中1例在手术前在病房接受了低流量氧疗(4 L/min)。

图2.

母体动脉血氧分压变化

Fig.2 Levels of maternal partial pressure of oxygen during the operation. A: Maternal partial pressure of oxygen at T1 (baseline). B: Pairing diagram of maternal partial pressure of oxygen at T2 (at delivery of the fetus) and T3 (at the end of the operation). Among them, there were 2 cases in the HFNC group and 9 cases in the CON group, and the value at T3 was lower than that at T2 and was less than 300. C: Box-plot of maternal partial pressure of oxygen at T2 and T3. *P<0.05.

图3.

母体动脉血气pH、pCO2和Lac散点图

Fig.3 Scatter plot of maternal pH, pCO2 and Lac. A: Maternal pH values. B: Maternal partial pressure of carbon dioxide. C: Maternal lactate values. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

2.3. HFNC组与COT组对母体次要观察指标的影响

本研究未记录到任何母体死亡事件。两组母体次要指标的差异没有统计学意义(表3)。COT组中1例患者在剖宫产术后10 d接受了破裂的右冠状窦动脉瘤和室间隔缺损修补术。HFNC组中有1例患者由于术后肺水肿需要接受无创通气呼吸支持。

表3.

母体次要指标

Tab.3 Maternal secondary outcomes

| Variables | COT (n=31) | HFNC (n=27) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory complications | 1 (3.2%) | 2 (7.4%) | 0.59 |

| Cardiovascular complications | 5 (16.1%) | 8 (29.6%) | 0.34 |

| Pyrexia | 1 (3.2%) | 1 (3.7%) | 1.00 |

| Pelvic adhesion | 8 (25.8%) | 10 (37%) | 0.40 |

| Postoperative leukocytosis# | 12 (38.7%) | 18 (66.7%) | 0.04 |

| Need for respiratory support## | 11(35.5%) | 13(48.1%) | 0.43 |

| Maternal ICU admission | 7 (22.6%) | 10 (37%) | 0.26 |

| Admission time in ICU (h)### | 78.42 (32, 94) | 142.43 (94, 253) | 0.11 |

| Length of stay (d) | 9.5±4.9 | 10.3±4.4 | 0.50 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 5.8±2.3 | 7±3.6 | 0.16 |

Data are presented as Mean±SD, median, (interquartile) or number of cases with percentages [n(%)]. #Analysis was limited to the normal preoperative leucocyte range[(4~10)×109/L]. Leukocytosis is defined as a WBC count greater than 10×109/L. ##Need for respiratory support, defined as presence of at least one of the following conditions within 72 h after surgery: use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or high-flow nasal cannula for at least 2 consecutive hours; supplement oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen of at least 0.3 for at least 24 continuous hours. ###Analysis was limited to ICU admission cases.

2.4. HFNC组与COT组对新生儿各项临床的影响

新生儿的各项临床指标以及脐静脉血气分析结果之间没有显著差异(表4)。其中1例早产儿(29周孕龄)因多器官功能衰竭而死亡。

表4.

新生儿各项临床指标

Tab.4 Neonatal outcomes

| Outcomes | COT (n=31) | HFNC (n=27) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intubation | 1 (3.2%) | 5 (18.5%) | 0.09 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 5 (16.1%) | 6 (22.2%) | 0.74 |

| Neonatal death≤72 hour | 0 (0) | 1 (3.7%) | 0.47 |

| Severe respiratory complication# | 9 (29%) | 12 (44.4%) | 0.22 |

| Admission to intermediate care nursery or NICU | 13 (41.9%) | 16 (59.3%) | 0.19 |

| Admission time in ICU (h)## | 212 (117, 364) | 215 (70, 541) | 0.91 |

| Umbilical cord around the neck | 6 (19.4%) | 3 (11.1%) | 0.48 |

| Gestational age (week) | 0.33 | ||

| >36 | 24(77.4%) | 19 (70.4%) | |

| 32-36 | 6(19.4%) | 4 (14.8%) | |

| 28-32 | 1(3.2%) | 4 (14.8%) | |

| Birth weight (kg) | 2757.3±489.8 | 2558.1±649.2 | 0.19 |

| Body length (cm) | 47.8±2.9 | 46.7±3.9 | 0.23 |

| Head circumference (cm) | 33.1±2 | 32.6±2.1 | 0.36 |

| 1 min Apgar≤7 | 0 (0) | 3 (11.1%) | 0.10 |

| 5 min Apgar≤7 | 0 (0) | 1 (3.7) | 0.47 |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 8 (25.8%) | 9 (33.3%) | 0.53 |

| Umbilical vein gas analysis### UV pH (7.23-7.44) | 1.00 | ||

| Low level | 1 (3.3%) | 0 (0) | |

| Normal | 29 (96.7%) | 26 (100%) | |

| High level | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Data are presented as Mean±SD, mean (median, interquartile) or number of cases with percentages [n(%)]. #Severe respiratory complication is defined as any of the following conditions within 72 h after birth: CPAP or HFNC for at least 12 hours; supplemental oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 0.3 or more for at least 4 continuous hours; mechanical ventilation; and death. ##Analysis was limited to ICU admission cases. ###Two umbilical venous samples were lost for analysis of ABG in each group.

2.5. HFNC组与COT组对术后随访的影响

术后随访数据分析中,HFNC组与COT组之间自我评估健康状况无显著统计学差异(P>0.05)。HFNC组有3例患者,COT组有1例患者在剖宫产后6个月内因心脏相关疾病需要门诊就诊。HFNC组中有1例患者因实施左心房粘液瘤切除术再次住院。两组之间的再入院率和门诊就诊次数相当。

3. 讨论

本研究指出,对于在椎管内麻醉下行剖宫产的孕妇,采用低浓度(40%)且高流量的氧疗,可以有效预防妊娠合并心脏病患者在麻醉期间母体氧饱和度下降。本实验探讨了更适合高危孕妇,尤其是妊娠合并心脏病患者围术期的氧疗模式。

妊娠合并心脏病母体低氧血症的原因可能包括V/Q失调、右向左分流、通气不足、弥散障碍、吸入氧分压降低、氧含量减少或携氧能力减弱。本研究中,两组患者的术前基线资料和心脏疾病类型相似,因此氧合指标的差异主要由不同氧疗方式引起。目前尚未明确异常SpO2或SaO2标准,因为组织缺氧的确切阈值尚未确定。因此,我们着重讨论该研究中氧合标准的选择,并比较HFNC和COT氧疗方式的优缺点。

对于存在心脏病的孕妇在椎管内麻醉下行剖宫产,必须防止低氧血症,因为这可能增加肺血管阻力,适当的氧疗是维持目标血氧饱和度范围内的必要手段[22]。临床上,低危妊娠妇女在剖宫产期间常规接受氧疗,被认为有助于防止母体血氧饱和度下降[23, 24]。然而,很少有研究评估高危孕妇,特别是妊娠合并心血管疾病的患者。有文献指出[25],对于高危孕妇,妊娠合并急性COVID-19感染期间建议维持SpO2水平在94%以上。当母体PaO2降至70 mmHg以下或血氧饱和度降至95%以下时,胎儿的氧输送会明显受影响[26]。Ukah等[27]指出,血氧饱和度可以预测子痫前期患者的不良母体结局,尤其是当SpO2值≤93%时[28]。本研究显示有5名孕妇患有高血压,我们在试验中将SpO2水平降至94%以下视为妊娠合并心脏病的氧合警告指标。

在COT组中,有2例患者出现短暂性SpO2低于94%的情况,她们被指导进行深呼吸,监测显示SpO2在3 min内上升到94%以上。指导产妇进行深呼吸后,根据观察结果决定是否需要进一步呼吸支持,考虑到孕产妇在分娩时对心脏疾病的担忧及胎儿娩出时的情绪波动。在本实验中,有2例患者的SaO2水平低于94%,但外周血氧饱和度显示的SpO2读数较高。与血气测量相比,外周血氧饱和度已被证明会高估血氧饱和度,尤其是在动脉血气SaO2低于90%的情况下。这种差异可能受到种族等因素的影响,与动脉血气测量值相比,亚洲人种个体的脉搏血氧仪读数可能高估5.8%[29]。因此,本研究选择结合动脉血气和外周血氧饱和度来分析氧合水平。

在此次随机对照实验中,我们从相同的低氧浓度(40%)开始观察两组之间的差异。最近的研究[30]表明,对于低流量氧疗(低于5 L/min),传统预测公式对供氧浓度的估算是不准确的。在低流量氧疗(2~4 L/min) 时,由于鼻腔是开放的补充系统,氧气源周围会有明显的空气补偿[31, 32]。Sorg等[33]指出,FIO2仅取决于供氧流量,而不取决于鼻导管的设计,因此我们认为HFNC组与COT组鼻导管之间的差异可忽略不计。此外,在临床实践中,PaO2/FIO2的比值是评估肺部疾病进展和氧合下降的有效指标[34]。本研究中,两组患者术前均无肺部疾病,且术前血红蛋白和血氧饱和度差异无统计学意义。综上所述,本研究选择了5 L/min的供氧流量。建立了动脉氧分压(PaO2:FIO2)≤300 mmHg的评价标准,认为这是评价通气和氧合的标准方法[35]。

本研究的受试者为年龄在18岁及以上的妊娠合并心脏病患者,这些患者在椎管内麻醉下接受宫产手术。妊娠合并心脏病患者可以采用自然分娩或剖宫产方式。椎管内麻醉通常用于循环相对稳定的剖宫产患者,这保证了本研究中术前患者基础数据的一致性。Pelaia等[36]探讨了HFNC治疗肺动脉高压患者的效果,发现这种治疗可以改善右心室功能。在本研究中,尽管HFNC组有更多的mWHO IV级患者,且该组血氧饱和度下降的发生率较低,但两组间差异无统计学意义,这表明需要进一步大样本量研究来确定妊娠合并心脏病患者是否从HFNC治疗中获益。

低血氧饱和度可能导致母婴不良结局,但高氧分压也可能增加新生儿不良事件的风险。目前,对于患有心脏病的孕妇,最佳氧分压范围尚不清楚。现有证据表明,母体氧疗采用50%的FIO2对胎儿氧分压没有显著影响,也不会增加自由基活性[37]。研究数据显示,母体氧分压水平与脐静脉pH及其他新生儿不良事件发生率之间未见明显差异,这与Raghuraman等[38]的研究结果一致。该临床试验提示,对于患有心脏病的孕妇,低浓度(40%)高流量氧疗可能是合适的选择。在HFNC组中,有5名新生儿需要气管插管,而COT组中仅有1名新生儿需要气管插管,这与HFNC组中有更多早产儿有关。在本研究中,两组新生儿的孕周没有显著差异,且没有证据表明母体HFNC治疗对早产婴儿有不良影响。

尽管HFNC治疗似乎有益,但仍存在潜在危害。我们发现HFNC组患者术后白细胞增多的发生率更高,尽管两组出现发热和其他炎症相关症状的比率相似。现有的证据未显示在接受剖宫产的女性中,高氧分压是否会增加手术部位感染风险[39-41],提示了进一步研究的必要性。

本研究存在若干限制和不足:伦理委员会要求在病房内保持入组患者的脉搏氧饱和度在94%以上,可能导致一些危重孕妇被排除在外;HFNC组退出率较高,由于2020年2月COVID-19爆发期间要求所有人佩戴口罩,导致我们未能补充更多数据;妊娠合并心脏病患者属高危人群,通常在病房内接受低流量氧疗,因此在本试验中有3例患者术前氧分压较高;我们未设定受试队列中氧分压的最佳水平。因此,需要进一步研究以探讨更精确的氧浓度和流量,从而使妊娠合并心脏病患者获益。

综上所述,在患有器质性心脏病的孕妇中,使用HFNC治疗可能更为优越,但这一结果仍需进一步验证。与传统氧疗相比,HFNC治疗在椎管内麻醉下行剖宫产的孕妇,采用40% FIO2显著预防了围手术期母体血氧饱和度的下降。尽管HFNC组患者术后白细胞增多更为明显,但未影响母体或胎儿的短期临床结果。

基金资助

广东省医学科学技术研究基金(B2021387)

参考文献

- 1. Okoth K, Chandan JS, Marshall T, et al. Association between the reproductive health of young women and cardiovascular disease in later life: umbrella review[J]. BMJ, 2020, 371: m3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ramlakhan KP, Johnson MR, Roos-Hesselink JW. Pregnancy and cardiovascular disease[J]. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2020, 17(11): 718-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hu KM, Hong AS. Resuscitating the crashing pregnant patient[J]. Emerg Med Clin North Am, 2020, 38(4): 903-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hoefnagel A, Yu A, Kaminski A. Anesthetic complications in pregnancy[J]. Crit Care Clin, 2016, 32(1): 1-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ducsay CA, Goyal R, Pearce WJ, et al. Gestational hypoxia and developmental plasticity[J]. Physiol Rev, 2018, 98(3): 1241-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tong W, Giussani DA. Preeclampsia link to gestational hypoxia[J]. J Dev Orig Health Dis, 2019, 10(3): 322-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng C, Liao AH, Chen CY, et al. A systematic review with network meta-analysis on mono strategy of anaesthesia for preeclampsia in Caesarean section[J]. Sci Rep, 2021, 11(1): 5630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hu JQ, Ye YX, Lu AY, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in patients with heart disease in China[J]. Am J Cardiol, 2020, 125(11): 1718-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rex S, Devroe S. Anesthesia for pregnant women with pulmonary hypertension[J]. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol, 2016, 29(3): 273-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Meng ML, Arendt KW. Obstetric anesthesia and heart disease: practical clinical considerations[J]. Anesthesiology, 2021, 135(1): 164-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corcione N, Karim H, Mina B, et al. Non-invasive ventilation during surgery under neuraxial anaesthesia: a pathophysiological perspective on application and benefits and a systematic literature review[J]. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther, 2019, 51(4): 289-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lapinsky SE. Management of acute respiratory failure in pregnancy[J]. Semin Respir Crit Care Med, 2017, 38(2): 201-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rochwerg B, Einav S, Chaudhuri D, et al. The role for high flow nasal cannula as a respiratory support strategy in adults: a clinical practice guideline[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2020, 46(12): 2226-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chaudhuri D, Granton D, Wang DX, et al. High-flow nasal Cannula in the immediate postoperative period: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Chest, 2020, 158(5): 1934-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rochwerg B, Granton D, Wang DX, et al. High-flow nasal cannula compared with conventional oxygen therapy for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: author’s reply[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2019, 45(8): 1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao HY, Wang HX, Sun F, et al. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy is superior to conventional oxygen therapy but not to noninvasive mechanical ventilation on intubation rate: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Crit Care, 2017, 21(1): 184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shippam W, Preston R, Douglas J, et al. High-flow nasal oxygen vs. standard flow-rate facemask pre-oxygenation in pregnant patients: a randomised physiological study[J]. Anaesthesia, 2019, 74(4): 450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tan P, Dennis AT. High flow humidified nasal oxygen in pregnant women[J]. Anaesth Intensive Care, 2018, 46(1): 36-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tan PCF, Millay OJ, Leeton L, et al. High-flow humidified nasal preoxygenation in pregnant women: a prospective observational study[J]. Br J Anaesth, 2019, 122(1): 86-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Preston KL, Butler P, Mudannayake R. Determining time to preoxygenation using high-flow nasal oxygen in pregnant women[J]. J Clin Anesth, 2020, 62: 109722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zimmerman ME, Hodgson DS, Bello NM. Effects of oxygen insufflation rate, respiratory rate, and tidal volume on fraction of inspired oxygen in cadaveric canine heads attached to a lung model[J]. Am J Vet Res, 2013, 74(9): 1247-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mohamed TM, Ahmed TM. Chestnut’s obstetric anesthesia: principles and practice, 6th ed[J]. Anesth Analg, 2019, 129(5): 1213. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chatmongkolchart S, Prathep S. Supplemental oxygen for Caesarean section during regional anaesthesia[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016, 3(3): CD006161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Siriussawakul A, Triyasunant N, Nimmannit A, et al. Effects of supplemental oxygen on maternal and neonatal oxygenation in elective cesarean section under spinal anesthesia: a randomized controlled trial[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2014, 2014: 627028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pacheco LD, Saad AF, Saade G. Early acute respiratory support for pregnant patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2020, 136(1): 42-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cole DE, Taylor TL, McCullough DM, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in pregnancy[J]. Crit Care Med, 2005, 33(10 Suppl): S269-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ukah UV, de Silva DA, Payne B, et al. Prediction of adverse maternal outcomes from pre-eclampsia and other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a systematic review[J]. Pregnancy Hypertens, 2018, 11: 115-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Millman AL, Payne B, Qu ZG, et al. Oxygen saturation as a predictor of adverse maternal outcomes in women with preeclampsia[J]. J D’obstetrique Gynecol Du Can, 2011, 33(7): 705-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Crooks CJ, West J, Morling JR, et al. Pulse oximeter measurements vary across ethnic groups: an observational study in patients with COVID-19[J]. Eur Respir J, 2022, 59(4): 2103246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fuentes S, Chowdhury YS. Fraction of Inspired Oxygen. 2022 Nov 29. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McDonald CF. Low-flow oxygen: how much is your patient really getting[J]? Respirology, 2014, 19(4): 469-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sharma S, Danckers M, Sanghavi DK, et al. High-Flow Nasal Cannula. Updated 2023 Apr 6. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sorg ME, Chatburn RL. Comparison of FIO2 Delivery With Low Flow vs High Flow Cannulas: A Simulation Study [J]. Respirat Care, 2021, 66(Suppl 10): 3597405. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Feiner JR, Weiskopf RB. Evaluating pulmonary function: an assessment of PaO2/FIO2[J]. Crit Care Med, 2017, 45(1): e40-e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Collins JA, Rudenski A, Gibson J, et al. Relating oxygen partial pressure, saturation and content: the haemoglobin-oxygen dissociation curve[J]. Breathe, 2015, 11(3): 194-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pelaia C, Armentaro G, Lupia C, et al. Effects of high-flow nasal Cannula on right heart dysfunction in patients with acute-on-chronic respiratory failure and pulmonary hypertension[J]. J Clin Med, 2023, 12(17): 5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ahuja V, Gombar S, Jaswal S, et al. Effect of maternal oxygen inhalation on foetal free radical activity: a prospective, randomized trial[J]. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand, 2018, 62(1): 26-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Raghuraman N, Temming LA, Doering MM, et al. Maternal oxygen supplementation compared with room air for intrauterine resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. JAMA Pediatr, 2021, 175(4): 368-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cohen B, Schacham YN, Ruetzler K, et al. Effect of intraoperative hyperoxia on the incidence of surgical site infections: a meta-analysis[J]. Br J Anaesth, 2018, 120(6): 1176-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Klingel ML, Patel SV. A meta-analysis of the effect of inspired oxygen concentration on the incidence of surgical site infection following cesarean section[J]. Int J Obstet Anesth, 2013, 22(2): 104-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dahlke JD, Mendez-Figueroa H, Rouse DJ, et al. Evidence-based surgery for cesarean delivery: an updated systematic review[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2013, 209(4): 294-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]