ABSTRACT

Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri (Xcc) is a bacterium that causes citrus canker, an economically important disease that results in premature fruit drop and reduced yield of fresh fruit. In this study, we demonstrated the involvement of XanB, an enzyme with phosphomannose isomerase (PMI) and guanosine diphosphate-mannose pyrophosphorylase (GMP) activities, in Xcc pathogenicity. Additionally, we found that XanB inhibitors protect the host against Xcc infection. Besides being deficient in motility, biofilm production, and ultraviolet resistance, the xanB deletion mutant was unable to cause disease, whereas xanB complementation restored wild-type phenotypes. XanB homology modeling allowed in silico virtual screening of inhibitors from databases, three of them being suitable in terms of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADME/Tox) properties, which inhibited GMP (but not PMI) activity of the Xcc recombinant XanB protein in more than 50%. Inhibitors reduced citrus canker severity up to 95%, similarly to copper-based treatment. xanB is essential for Xcc pathogenicity, and XanB inhibitors can be used for the citrus canker control.

IMPORTANCE

Xcc causes citrus canker, a threat to citrus production, which has been managed with copper, being required a more sustainable alternative for the disease control. XanB was previously found on the surface of Xcc, interacting with the host and displaying PMI and GMP activities. We demonstrated by xanB deletion and complementation that GMP activity plays a critical role in Xcc pathogenicity, particularly in biofilm formation. XanB homology modeling was performed, and in silico virtual screening led to carbohydrate-derived compounds able to inhibit XanB activity and reduce disease symptoms by 95%. XanB emerges as a promising target for drug design for control of citrus canker and other economically important diseases caused by Xanthomonas sp.

KEYWORDS: Xanthomonas , citrus canker, GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase, phosphomannose isomerase, inhibitors, citrus protection, innovation

INTRODUCTION

Citrus canker is a disease caused by the bacterium Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri (Xcc), which manifests as circular, raised, cortical, and brown lesions on leaves, branches, and fruits (1). In more severe cases, it can lead to premature fruit drop, directly impacting citrus production (2). In citrus-growing regions where the disease is endemic, a range of control measures is employed to minimize crop loss, including the use of resistant or less susceptible cultivars, windbreaks around the orchard perimeter, and frequent application of copper-based bactericides during spring and summer months (3, 4). While copper-based treatments have shown effectiveness in managing citrus canker, their long-term use may have negative environment implications and pose potential risks to consumers, highlighting the necessity for the development of novel disease management strategies.

Previous studies carried out at Laboratory of Biochemistry and Applied Molecular Biology (from the Portuguese "Laboratório de Bioquímica e Biologia Molecular Aplicada, LBBMA") at the Federal University of São Carlos by Carnielli and colleagues (5) demonstrated a 4.8-fold increase in the abundance of the XanB enzyme on the surface of Xcc cells grown in vivo compared to those grown in vitro. This enzyme is associated with the production of xanthan gum, an exopolysaccharide known to play a crucial role in bacterial defense by protecting cells against dehydration in harsh environments (6), as well as in pathogen-host interactions (7).

XanB is a metalloenzyme with phosphomannose isomerase (PMI) or mannose-6-phosphate isomerase activity, catalyzing the interconversion of fructose-6-phosphate and mannose-6-phosphate. Additionally, the enzyme possesses GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase (GMP) activity, which catalyzes the synthesis of guanosine mannose diphosphate (GDP-mannose) (8). The putative PMI-GMP enzyme encoded by the ORF XAC3580 in Xcc [National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)] is bifunctional, known as type II (9), consists of 467 amino acid residues, and belongs to the family of mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase and mannose-6-phosphate isomerase (10). Notably, this enzyme is conserved in various other microorganisms and serves as a potential therapeutic target in animal pathogens such as Candida albicans (11), Mycobacterium smegmatis (12), and Leishmania mexicana (13).

Computational chemistry tools have been employed in designing novel drugs that interact with specific targets, aiming to prevent the progression of diseases (14, 15). Virtual screening is a commonly used computational technique for drug discovery, which identifies compounds capable of binding to a particular protein or enzyme (16). This approach involves two main methods: ligand-based and structure-based methods (17). The ligand-based method analyzes electronic, structural, physicochemical, and molecular similarities between different ligands and suggests a binding mechanism to a specific receptor (18). Ligand similarity methods are based on the assumption that compounds similar to a known active ligand for a given target are more likely to be active than those without similar characteristics (19). Structure-based methods include computational approaches to analyze the structure of the target. One of the most used techniques within this method is molecular docking, which employs a scoring function to indicate ligands with greater affinity for the active binding site (20, 21).

Since the 1980s, computational techniques have been utilized for drug discovery, particularly for human consumption (22). However, there is significant potential to develop novel and safer products for disease and pest control in agriculture. Therefore, this study aims to demonstrate the essential role of GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase activity of XanB in the pathogenicity of Xcc and to screen and evaluate inhibitors of this activity as sustainable alternative to copper for protecting against citrus canker.

RESULTS

xanB is an essential gene for Xcc pathogenicity in Citrus aurantifolia

The colonies of the deletion mutant and complemented strains (XccΔxanB and XccΔCxanB, respectively) selected on sucrose were assessed for gene deletion and complementation by PCR. The amplicons were of the expected sizes, being 3.5 kb for the wild type (Fig. S1, lane 1) and complemented strains (Fig. S1, lane 7), and 2 kb for the mutant strain (Fig. S1, lane 2). As expected, no PCR amplification was obtained using the pNPTS138_xanB deletion vector as a template (Fig. S1, lane 4). To confirm that the amplified PCR product from these strains corresponded to the chromosomal regions of interest, digestion with EcoRI was performed, which resulted in two 1-kb bands for XccΔxanB (Fig. S1, lane 3) and a 1.5-kb band for the coding region of the xanB gene, and another 1-kb band referring to the two flanking regions of 1 kb each for XccΔCxanB (Fig. S1, lane 8).

The mutant, complemented, and wild-type strains were evaluated for pathogenicity and virulence in Citrus aurantifolia through syringe infiltration and spraying. Twenty days post-infiltration, the leaves were detached and digitally recorded to compare the infection (Fig. 1). In the spray test, the bacterial suspension and saline solution were each sprayed, and leaves were digitally recorded 28 days post-spraying (Fig. 2).

Fig 1.

In vivo pathogenicity assay by infiltration of Xcc, XccΔxanB, and XccΔCxanB into Citrus aurantifolia leaves. Plants of C. aurantifolia were utilized for comparative evaluation of pathogenicity and virulence of Xcc, XccΔxanB, and XccΔCxanB. The positive control image (Xcc) is identical to that used in our previous work for the in vivo assays for xylA gene mutants (23), since both assays were carried out together. All plants had four leaves of independent branches infiltrated with the three strains and the negative control using saline (0.9% NaCl). Leaves were documented 20 days post-inoculation.

Fig 2.

In vivo pathogenicity assay by spraying of Xcc, XccΔxanB, and XccΔCxanB in Citrus aurantifolia leaves. Potted Citrus aurantifolia plants kept in a greenhouse were used for comparative evaluation of the pathogenicity and virulence of Xcc, XccΔxanB, and XccΔCxanB. Ten milliliters of each bacterial culture and the same volume of saline solution (negative control) were sprayed on four plants. Leaves were scanned 28 days post-inoculation.

The wild-type Xcc strain induced the typical citrus canker symptoms, as expected, whereas the deletion of xanB reduced pathogenicity for XccΔxanB in both infiltration and spray inoculation. Furthermore, the complemented strain XccΔCxanB showed a phenotype reversion. Both Xcc and XccΔCxanB strains caused similar degrees of water soaking and disease severity (Fig. 1 and 2).

xanB gene is involved in motility, biofilm formation, and UV resistance of Xcc

The motility capacity was evaluated by measuring the diameter of the colonies, which were 2.70 ± 0.02, 1.15 ± 0.02, and 2.72 ± 0.09 cm for Xcc, XccΔxanB, and XccΔCxanB, respectively (Fig. 3). XccΔxanB showed a reduction in motility of approximately 60% compared to wild-type Xcc and the complemented strain XccΔCxanB, indicating that the xanB gene plays a role in this characteristic related to bacterial pathogenicity.

Fig 3.

Motility of xcc, XccΔxanB, and XccΔCxanB. Cultures were pipetted in the center of petri dishes with 0.7% Luria-Bertani agar. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 48 h without shaking and were digitally recorded (on the left). The diameter of the colonies obtained was measured using ImageJ software. The calculated averages are presented graphically (on the right). Error bars indicate the absolute standard deviation of each of the triplicates. Columns followed by the same letter do not show significant difference using Tukey’s test (P = 0.05).

The three strains were evaluated for biofilm formation over 24, 48, and 72 h. After 24 h, the biofilm produced by XccΔxanB was higher than that of Xcc and XccΔCxanB. However, after 48 and 72 h, this pattern was significantly reversed, with biofilm formation in XccΔxanB being 4.5 and 14.5 times lower, respectively, than in Xcc (Fig. 4). The biofilm produced by XccΔCxanB was similar to that of Xcc, confirming the effect of xanB depletion on biofilm formation in XccΔxanB.

Fig 4.

Biofilm formation by Xcc, XccΔxanB, and XccΔCxanB. Cultures were evaluated for biofilm formation. The results are presented as the average of the ratio between the crystal violet absorbance at 595 nm and the optical density of each bacterial culture immediately before the measurement of biofilm formation (A595 nm/OD595 nm). Measurements were taken at 24, 48, and 72 h after incubation. Error bars indicate the absolute standard deviation of each of the sextuplicates. Columns followed by the same letter do not show significant difference using Tukey’s test (P = 0.05).

The xanB gene also plays a role in Xcc resistance to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. XccΔxanB was found to survive for a period three times shorter than Xcc. The wild-type level of UV resistance was restored in XccΔCxanB through xanB complementation (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

Evaluation of resistance to ultraviolet (UV) radiation by Xcc, XccΔxanB, and XccΔCxanB. Cultures were evaluated for survival after exposure to UV radiation. The results are presented in percentage of survival relatively to the controls of each bacterial strain not exposed to UV radiation. Error bars indicate the absolute standard deviation of each of the triplicates. Columns followed by the same letter do not show significant difference using Tukey’s test (P = 0.05).

XanB is a bifunctional enzyme

Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) transformed with the pET41a_xanB vector and induced with isopropyl-ß-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) is expected to produce an 85-kDa recombinant protein fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST), with 51 and 26 kDa corresponding to the xanB and GST coding regions, respectively, and an additional 8-kDa fragment encoded by the pET41a vector. SDS-PAGE analysis showed that the recombinant protein was predominantly present in the soluble fraction (Fig. S2).

The isomerase activity of the recombinant XanB was confirmed using Seliwanoff’s reagent (Fig. S3) and a coupling method with PGI and G6PD (Fig. S4). The second predicted activity of the recombinant XanB was also confirmed by the pyrophosphatase coupling method (Fig. S5).

Xcc XanB tridimensional modeling and in silico searching for XanB inhibitors

Construction and evaluation of Xcc XanB and human PMI homology models

In the absence of a deposited Xcc XanB crystallographic structure in the Protein Data Bank, a homology model was employed to discover novel potential inhibitors using a structure-based drug design. To construct the homology model for Xcc XanB, the National Institutes of Health BLASTp server (24) was utilized, which identified the following homologous structures with high-resolution crystallographic data (ranging from 1.9 to 2.35 Å): PDB IDs 2CU2, 2 × 5S and 2QH5, sharing 38%, 40%, and 40% sequence identity, respectively, with Xcc XanB. Additionally, the PDB ID 1H5R, with 29% sequence identity and containing a ligand (the substrate) located within the enzyme’s active site, was also considered/selected.

The selection of these crystallographic structures as templates in the homology modeling process included a PMI structure in complex with a ligand, specifically, the B chain of the PDB ID 1H5R protein structure. Given that all the selected structures share above 25% sequence identities with Xcc XanB, they are likely to exhibit potential structural and functional similarities with the modeled structure.

Based on the sequences of the Xcc XanB homologs used as templates, we performed a multiple alignment analysis using the referred templates and Xcc XanB. Sequence alignments were conducted using the Clustal Omega web server (25), and the four crystallographic structures mentioned above were superimposed using the Discovery Studio software to verify the quality of the alignment.

When comparing both alignments, one obtained using only Clustal Omega and the other refined, some differences were observed. Certain gaps were suggested based on the templates’ structural superpositions, with the most evident one occuring in the PDB ID 2QH5 structure, where a gap was added between the Gly11 and Tyr12 amino acid residues (Fig. S6).

Finally, the MODELLER-generated final model was validated using WHAT IF and PROCHECK, including the Ramachandran Plot, Verify-3D, ERRAT, and PROVE methodologies (described in the supplemental material). The results confirmed the suitability of the models in structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) simulations.

A human PMI model was also constructed and validated using the same protocol as the Xcc XanB model to facilitate the evaluation and comparison of the two enzymes’ active sites, which are distinct. This approach enabled us to obtain specific inhibitors for Xcc XanB.

Model and methodology validation

We performed a redocking study (26) to select the appropriate docking program for our simulations (GOLD and GLIDE). The program that demonstrated the highest pose conformity and an root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) below 2.5 Å, which is considered a partial success by the aforementioned authors (27, 28), was GOLD (Fig. 6). Therefore, GOLD was selected for our future docking simulations in comparison with the crystallographic ligand (glucose-1-phosphate).

Fig 6.

Superposition between the Xcc XanB model (ribbon representation in pink) and the PDB ID 1H5R structure (ribbon representation in green). The figure shows the docking poses of the glucose-1-phosphate ligand in comparison to the crystallographic pose (stick representation, colored by atoms), inside the XanB GMP active site, when using the GOLD (stick representation, in yellow) and GLIDE (stick representation, in blue) software.

Models’ validation

After selecting and refining the final Xcc XanB model, we evaluated its efficiency for virtual screening studies using the receiver operator characteristic curve (ROC) and area under the curve (AUC) (29, 30). A database was constructed using 30 ligands with reported biological activity values (IC50) from the BindingDB web server (31) (supplemental material).The AUC ROC value obtained for this study with our model was 0.760, which was close to the ideal value of 1.

For human PMI, the studies also showed favorable results, with an obtained AUC value of 0.792, which is considered significant when close to the ideal value of 1.

Therefore, based on these validation results, we can confirm that the models built for both Xcc and human PMI are capable of distinguishing between more and less potent XanB inhibitors selected from the BindingDB structures repository. Furthermore, the Xcc model is suitable for subsequent virtual screening studies. Additional information about the model validation can be found in the supplemental material.

Virtual screening procedures

For virtual screening purposes, we divided the compound databases into two groups. The first group consisted of ZINC, Drugs FDA, Chembridge and Maybridge, while the second group included the Princeton and IBS databases. In the virtual screening simulations involving compounds from the first group, we selected the 2,000 top-ranked compounds from each database. These compounds were obtained by virtual screening based on shape similarity and were scored according to their Tanimoto similarity indexes (ROCS_TanimotoCombo). Then, we retrieved the 1,000 top-ranked results for each base based on the Tanimoto index (EON_ET_Combo), resulting in a total of 7,000 surviving compounds after the first stage of our protocol.

The compounds obtained in the previous step underwent docking simulations, and the 500 top-ranked ones were selected based on the GOLD Fitness function for each database. Subsequently, these compounds had their ADME/Tox properties predicted, resulting in 117 compounds in this first group of compound databases. The next stage involved visual inspection of the binding modes predicted for these compounds in relation to the Xcc XanB model, from which only 40 molecules were selected as potential and promising candidates for Xcc XanB inhibition.

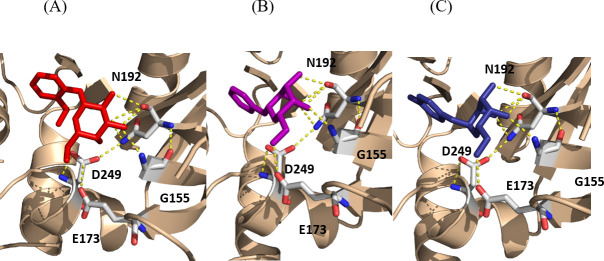

Finally, 33 compounds were commercially acquired, and three compounds emerged as the most promising, referred to as i1, i2, and i3. According to our docking simulations, these three selected inhibitors potentially interact with the same amino acid residues (Gly155, Glu173, Asn192, and Asp249). Two of them (i1 and i2) establish all these interactions, with Gly155 acting as a hydrogen bond donor, while the other amino acids (Glu173, Asn192, and Asp249) act as hydrogen bond acceptors (Fig. 7).

Fig 7.

Stick representation of docking poses for the selected inhibitors i1 (A), i2 (B), and i3 (C) inside the Xcc XanB (in ribbon representation) GMP active site, with hydrogen bonds represented in yellow dashed lines. Main residues of the XanB active site are depicted here with labels.

The other compound, i3, demonstrates potential interactions with Gly155, serving as a hydrogen bond donor, though its interactions with other amino acid residues, such as Glu173 and Asn192, are distinct, excluding any interaction with the Asp249 residue (Fig. 7). In the context of virtual screening simulations for compounds from the second group, we initially identified the top 5,000 compounds using similarity-based virtual screening focused on the shape of the ligand. These compounds were evaluated based on their Tanimoto similarity indexes, leading to the selection of the top 3,000 compounds by this metric. Following this, docking simulations were conducted on these compounds, and the 500 with the highest scores, as determined by the GOLD Fitness function, were chosen from each database. The ADME/Tox properties of these compounds were then predicted, narrowing the field to 13 promising candidates from this second group of compound databases. A final visual inspection of these molecules’ potential binding modes with the Xcc XanB model was performed, yet none of the compounds met the criteria to proceed beyond this stage of the protocol.

Pyrophosphorylase activity of the recombinant XanB is inhibited by the selected compounds

The inhibition assay for the pyrophosphorylase activity of recombinant XanB confirmed the effectiveness of the three compounds at 1 mM, with inhibition percentages of 54.96% (SD = 12.66, P = 0.035), 74.11% (SD = 6.63, P = 0.0042) and 78.01% (SD = 21.32, P = 0.0038) for i1, i2, and i3, respectively (Fig. 8). There was no statistical difference in the inhibition percentages when comparing the three compounds.

Fig 8.

Pyrophosphorylase activity of the recombinant XanB in the presence of the potential XanB inhibitors. In silico selected inhibitors i1, i2, and i3 at 1 mM were tested for the ability to inhibit the pyrophosphorylase activity of the recombinant XanB. The inhibition percentage was calculated in relation to the reaction that replaces the volume of inhibitors by buffer 50-mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 100-mM NaCl.

Compounds i1 and i2 were also tested for their ability to inhibit the isomerase activity of recombinant XanB (Fig. S7). For i3, it was not possible to determine its inhibitory effect due to its strong absorbance at 340 nm (data not shown). The negative control, which did not include recombinant XanB, exhibited lower absorbance at 340 nm than the reaction containing the enzyme (enzyme test) (P < 0.0001), as previously observed (Fig. S4). However, there were no significant differences between the positive control (without inhibitor) and the reactions containing i1 (P = 0.4318) and i2 (P = 0.9984), indicating that both compounds do not inhibit the isomerase activity of recombinant XanB.

The docking pose of the most potent inhibitor of the pyrophosphorylase activity of recombinant XanB investigated (i3) is represented inside the Xcc XanB structure (Fig. 9).

Fig 9.

Surface, stick, and ribbon representations of i3 located inside the XanB active site. In this figure, the i3 inhibitor is visualized in stick representation (atoms in blue); selected XanB GMP active site residues are visualized in stick representation (colored by atoms); and PMI is visualized in surface as well as ribbon representations (in light brown).

XanB inhibitors protect C. aurantifolia and C. sinensis against citrus canker

The protective effect of XanB inhibitory compounds against Xcc was evaluated 35 days after spray inoculation of Xcc in C. aurantifolia and C. sinensis (Fig. 10). In both hosts, the three selected inhibitors reduced the severity of citrus canker, as indicated by the number of lesions per leaf area. In C. aurantifolia, inhibitor 3 reduced disease severity by 95.4% compared to the untreated control (P < 0.0001). For inhibitors 1 and 2, disease control reached 65.9% (P < 0.0001) and 90.4% (P < 0.0001), respectively.

Fig 10.

Potential of the inhibitors for protection of C. aurantifolia and C. sinensis against citrus canker. For each treatment, 10 leaves from three plants were sprayed on both surfaces with inhibitors i1, i2, i3, water (control), and copper oxychloride (the latter only for the assay with C. sinensis). The plants were spray-inoculated 24 h after the application of the inhibitors using Xcc suspension at 106 CFU/mL and kept in a plastic humid chamber for 24 h in a humid room. Marked leaves from of each plant were evaluated 35 dpi, and the number of lesions on each leaf was divided by the leaf area. Error bars indicate the absolute standard deviation of each of the triplicates. Columns followed by the same letter do not show significant difference using Tukey’s test (P = 0.05).

In C. sinensis, the severity of citrus canker was reduced by inhibitors 1, 2, and 3 by 82.0% (P = 0.0018), 76.5% (P = 0.0031), and 74.9% (P = 0.0036), respectively. This level of control was similar to that provided by copper treatment on C. sinensis, which reduced the disease symptoms by 74.9% (P = 0.0036).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we conducted functional characterization of the Xcc xanB gene, confirming its predicted enzymatic activities of PMI and GMP and demonstrating its essentiality for Xcc pathogenicity. Our research group previously identified XanB, encoded by the ORF XAC3580, as a potential contributor to pathogenicity through differential surface proteomics analysis of Xcc cells under in vivo and in vitro conditions (5). XanB was also identified in a proteomic analysis of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris interacting with Brassica oleracea (32). Additionally, we successfully selected XanB inhibitors capable of protecting C. aurantifolia and C. sinensis against citrus canker, further highlighting the potential of XanB as a target for disease control strategies (5, 33).

Deletion of a single gene resulting in the loss of pathogenicity is not so common in plant pathogens. Several mutant strains of Xcc have exhibited reduced virulence (32, 34–37). Deletion of xanB led to the inability of Xcc to induce symptoms in the host using both spray and infiltration methods (Fig. 1; Fig. 2). This suggests that the absence of symptoms is due to the inability not solely to survive in the epiphytic environment or to invade the host but also to colonize the apoplastic milieu. It is worth highlighting that the complemented strain XccΔCxanB regained its pathogenicity and virulence phenotypes, confirming that the loss of pathogenicity in XccΔxanB resulted from the deletion of xanB.

In our study, we observed increased severity of symptoms of the complemented strain relatively to the wild strain, which is an intriguing finding. This variation in disease severity could be attributed to several factors beyond mere biological variability. Environmental and experimental conditions, including slight differences in the age and health status of the plants as well as the microenvironment at the time of inoculation, may influence the expression of virulence factors and the host’s susceptibility to infection. Moreover, the influence of epigenetic factors on the virulence and genetic characteristics of bacterial plant pathogens has been documented (38). In constructing the complemented strain, we reintroduced the xanB gene into its original genomic locus, being that this copy has EcoRI flanking sites which were incorporated during construction of the plasmid used for complementation. These sites are absent in the wild-type strain, providing unique targets for Xcc EcoRI methylases in the complemented strain.

As demonstrated by Baránek and colleagues (38), the application of DNA demethylating chemicals has clear effects, with treated strains exhibiting reduced virulence. These findings suggest that methylation patterns can significantly affect the pathogenicity of Xcc strains, potentially explaining the observed increase in virulence of the complemented strain in our experiments relatively to the wild strain. This hypothesis suggests a nuanced understanding of pathogenicity, where modification of xanB vicinity can inadvertently affect virulence through epigenetic mechanisms.

In addition to the pathogenicity analyses previously described, growth tests were conducted to assess the impact of the xanB gene deletion on the growth capability of the XccΔxanB under nutrient-rich conditions. For this purpose, both the mutant and wild-type strains were cultured in a rich growth medium, such as Luria-Bertani (LB), and their growth was monitored (results not shown). The growth capacity of the xanB mutant strain was significantly affected, exhibiting a reduced growth rate compared to the wild-type strain. These findings indicate that the deletion of the xanB gene not only compromises Xcc pathogenicity but also adversely affects its growth in nutrient-rich environments. This observation suggests a potential role of the xanB gene in Xcc adaptation and survival under varying environmental conditions, in addition to its known role in pathogenicity.

The involvement of XanB in the synthesis of GDP-D-mannose, a precursor in the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) production pathways, emphasizes the already known importance of this exopolymer for the Xcc infection process. LPS constitutes the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and acts as an elicitor molecule during plant-pathogen interactions. It triggers defense responses, including the generation of reactive oxygen species (39), the expression of defense-related genes (40), and the influx of cytosolic calcium (41), which induce programmed cell death (42).

The triggering of host defense responses is partially responsible for the appearance of symptoms during citrus canker pathogenesis. In X. campestris pv. campestris, interruption of the xanB gene with a transposon produced a strain with an altered profile of LPS, lacking the outer portion of the core sugar and O-antigen and an incomplete inner portion of the core sugar. As expected, the mutation caused the absence of mannose units in LPS and decreased the amounts of galacturonic acid and glucose. Consequently, the mutant strain elicited milder host defense responses, including oxidative burst (43), which can also be expected for XccΔxanB. Thus, it is possible to suggest that the absence of symptoms of XccΔxanB (Fig. 1; Fig. 2) is due to the host’s inability to recognize bacterial LPS, leading to a weak oxidative defense response. Although the ability to remain unrecognized by the host seems advantageous for XccΔxanB, this strain was not able to successfully infect the host, which can be explained by other factors.

Cell adhesion and biofilm formation are critical factors for the success of the Xcc infection process. XccΔxanB exhibited a 61.15% reduction in motility compared to the wild type, a phenotype also restored by XccΔCxanB (Fig. 3), suggesting that the xanB gene is involved in this crucial characteristic of the infectious process. In Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, xanB mutation using a transposon impaired bacterial motility, which was attributed to the lack of the polar flagellum in the mutant cells (44). Therefore, the decreased motility of XccΔxanB may have contributed to its loss of pathogenicity. As is known, phytopathogens use motility mechanisms to reach nutrient-rich surfaces and plant tissues (45). Xcc motility is conferred by a single polar flagellum that allows the bacterium to glide in the epiphytic environment and in the apoplast (46). The disruption of the wxacO gene, which participates in LPS synthesis, had a negative impact on Xcc (47). Thus, although it is necessary to confirm that XccΔxanB is defective in LPS production and polar flagellum formation, it is possible that the reduction in motility is related to these two components acting in the pathogenesis of citrus canker.

Biofilm formation is a common ability of bacteria to aggregate in matrices, allowing adhesion to surfaces and providing a dynamic way of life for bacterial populations (48). Although the XccΔxanB strain showed higher biofilm formation than the wild type and XccΔCxanB in the first 24 h, after 48 and 72 h, the pattern was reversed (Fig. 4). This unexpected behavior in the first hours was also observed for Photorhabdus luminescens, where PMI-GMP was related only to the biofilm maturation stage and not to the initial stage of its development (48).

A large-scale mutagenesis approach using transposons identified 92 genes related to biofilm formation in Xcc, including xanB, which supports the data obtained here using a different methodology to mutate the target gene (49). The formation and maturation process of biofilms involves the participation of exopolysaccharide (EPS) and LPS, polymeric substances that act in cell cohesion and intercellular communication (50). Specifically for Xcc, motility and adhesion are necessary characteristics for the early stages of biofilm formation, while biofilm maturation depends on LPS and EPS, such as xanthan gum (47, 49). Therefore, the participation of the xanB gene in the LPS and EPS biosynthesis pathways can also explain the loss of pathogenicity of XccΔxanB. Furthermore, biofilm formation promotes the epiphytic survival of Xcc (51), protects against environmental stresses, such as resistance to ultraviolet radiation, and also acts in defense against host response mechanisms (52). Thus, the reduction in biofilm formation presented by XccΔxanB may explain the in vivo results.

XccΔxanB showed threefold lower survival to UV compared to the wild type, and this phenotype was restored by gene complementation (Fig. 5). The increased susceptibility of XccΔxanB to ultraviolet radiation can be explained by the role of XanB in the xanthan biosynthesis pathway, as this EPS has been associated with resistance to various environmental stresses, including exposure to UV radiation (53).

The XanB enzyme is bifunctional, as previously described. In silico selected compounds inhibited its pyrophosphorylase activity, which affects the formation of GDP-mannose from mannose-1-phosphate and GTP (54). GDP-mannose is one of the components necessary for the formation of xanthan gum (55), which is a survival mechanism for bacteria as it helps to protect against ultraviolet radiation, freezing, and desiccation. The role of the XanB enzyme on the bacterial surface is still unknown. Although many proteins are involved in Xcc pathogenicity and complex secretion systems have been described as important for successful colonization of the citrus host, this study showed that the absence of a single protein, XanB, was sufficient to cause the loss of bacterial infectivity, evidencing its high potential as a target of biotechnological interest.

The three compounds interact with the amino acids Gly155, Glu173, and Asn192, showing that these residues play a fundamental role in inhibiting the GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase activity, for which they were specifically designed. Inhibitor i3 does not interact with Asp249, unlike i1 and i2. However, this interaction does not appear to be relevant for the inhibition process, as there was no statistical difference between the three compounds. The inhibitors were specifically designed to target the pyrophosphorylase activity of the enzyme at its active site, not for the isomerase site, as mentioned earlier.

This study opens up future perspectives with broader implications, starting from the premise that XanB is either a target of biotechnological interest in Xcc and is absent in the genome sequences of Citrus hosts at NCBI, particularly C. sinensis (orange), C. delicious (tangerine), and C. limon (lemon). Moreover, annotated genomes of over 20 species belonging to the genus Xanthomonas, which are responsible for causing several diseases in economically important crops, show the presence of XanB homologs sharing 95% identity or more with XanB of Xcc. Finally, the possibility of molecular optimization of the inhibitors also suggests a promising way forward for future investigation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Detailed descriptions are given in Supplemental Text.

Bacterial strains, culture media and conditions, and general procedures

Cultures of Xcc and E. coli strains, DH5α and BL21 (DE3), were grown on LB agar (Sigma-Aldrich) or LB broth (Sigma-Aldrich), under incubation at 30°C for Xcc and 37°C for E. coli strains, and 250 rpm. For the biofilm formation assay, cultures were grown in XAM-M medium (56). Molecular biology procedures were carried out following Ausubel’s protocols (57) with modifications when necessary.

Construction of xanB deleted mutant and complemented strain

The mutant strain was generated via double homologous recombination between xanB flanking regions cloned in the pNPTS138 plasmid and the corresponding regions of Xcc genome as standardized by our research group (33, 58, 59). To construct the deletion plasmid, 1-kb regions flanking the ORF XAC3580 were amplified by PCR using Xcc genomic DNA as template and the oligonucleotides specific for the upstream and downstream fragments (Table S1). The deletion plasmid pNPTS138_xanB was utilized to transform Xcc by electroporation (60), and the kanamycin-resistant colonies were grown repeatedly in LB and plated on sucrose 10%. An Xcc mutant colony (XccΔxanB) was confirmed by PCR using the ko-F and ko-R oligonucleotides (Table S1).

A complemented strain was also obtained by double homologous recombination. The PCR-amplified xanB gene was cloned into the EcoRI unique site of pNPTS138_xanB deletion vector (between the two flanking fragments), producing the complementation vector pNPTS138_CxanB, which was used in the XccΔxanB mutant transformation to obtain the complemented strain XccΔCxanB.

Pathogenicity tests in Citrus spp. for mutant and complemented strains

The pathogenicity of Xcc, XccΔxanB, and XccΔCxanB strains was evaluated in Citrus aurantifolia plants by infiltration and spraying methods. For both assays, isolated colonies were initially cultured in 5 mL of LB broth until reaching an optical density (OD595 nm) of 0.4. Subsequently, 100 µL of these cultures was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The resulting pellets were resuspended in 10 mL of 0.9% saline solution, yielding a bacterial suspension of approximately 106 colony-forming unit (CFU)/mL.

In infiltration assays, 150 µL of the bacterial suspensions (or 0.9% saline solution for the negative control) was injected into the abaxial side of the leaves using a 5-mL syringe. To ensure comprehensive assessment, four leaves from independent branches were infiltrated for each condition, with all plants receiving both bacterial and saline solution treatments (23).

For the spraying assay, 10 mL of the bacterial suspensions (or 0.9% saline solution for the negative control) was applied onto quadruplicate plants. The most susceptible leaves were marked at the outset to facilitate consistent application and assessment.

Both infiltration and spraying assays were conducted on two separate days, employing two biological replicates (independent cultures) each time and four experimental replicates (four leaves for infiltration and four plants for spraying) for each bacterial line. The leaves and plants were photographically documented after 20 days (for infiltration) and 28 days (for spraying), allowing for a visual comparison of the symptoms associated with the infectious process.

Motility, biofilm, and UV resistance assays for xanB deletion mutant and complemented strain

Swarming motility of the Xcc, XccΔxanB, and XccΔCxanB strains was assessed following the protocol previously described (61). Bacterial cells were inoculated in the center of the petri dishes containing LB solid medium. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 48 h without shaking. Colony diameter was measured and statistical analysis (Tukey’s test) was performed.

Biofilm formation by XccΔxanB and XccΔCxanB strains was carried out in 96-well plates containing XAM-M medium by incubation at 30°C without shaking for 24, 48, and 72 h. After staining with crystal violet and washes, residual dye from the adhered cells was solubilized and quantified.

Resistance to UV radiation was carried out by exposing Xcc, XccΔxanB, and XccΔCxanB cells to UV radiation from a biological safety cabinet (47). The Xcc, XccΔxanB, and XccΔCxanB strains were cultured in 5 mL of LB at 37°C for 16 h. Subsequently, the optical density at 595 nm was adjusted to 0.1 (approximately 3.107 CFU/mL). In triplicate, 100 µL of these cultures contained in Eppendorf tubes was exposed to a 15-W lamp that produces UV light with a spectrum predominantly peaking at 253.7 nm at a distance of 60 cm from the light source. After 15 minutes of exposure, serial dilutions were performed, and the samples were plated on LB agar for CFU counting and calculation of the survival percentage. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using Tukey’s test.

xanB gene cloning, recombinant expression, and purification

The xanB coding sequence (ORF XAC3580) was PCR-amplified using genomic DNA from Xcc and cloned into the pJET v.1.2 vector and subsequently into the pET41a vector (Novagen). After transformation of E. coli DH5α and plating, the plasmid from a kanamycin-resistant clone (pET41a_xanB) was used to transform E. coli BL21 (DE3). A transformant was grown in LB containing kanamycin, and 0.1-mM IPTG was added. After cell sonication, the protein (recombinant XanB) was purified from the soluble fraction by immobilized-metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) and elution with glutathione. After analysis by SDS-PAGE (62), the last eluate fraction was dialyzed and quantified by the UV absorption method.

XanB homology modeling and virtual screening for inhibitors

Construction, evaluation, and validation of the model

The models were generated following the traditional steps of a homology modeling procedure. BLASTp search and selection of homologous structures containing crystallographic data (63) were used as templates. Sequences of these crystallographic structures were aligned with the query protein by using Clustal Omega (25). Models were generated for the query protein using MODELLER (64), and validation was performed by selecting the best model proposal using WHAT IF and SAVES v.5 suite (65).

Library preparation

Several commercially available databases for this study, including ZINC (subcollections Natural Stock, Drug-database, and Drug-like) (66, 67), BindingDB subdivision Drugs FDA (68), ChemBridge (with subcollections such as DIVERSet-EXPEXPRESS-Pick Collection and DIVERSet Core Library) (69), Maybridge subdivision Screeening Collection (70), Princeton and IBS (subdivision Natural e Synthetic), which collectively contain approximately 20 million marketable compounds. The compounds were prepared using OMEGA software (71) for conformers generation, with only one conformation per molecule, a strain energy of 9 kcal/mol, and a 0.6-Å cutoff for conformer differentiation (72).

Ligand preparation

For our ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS) studies we used the G1P ligand, retrieved from the PDB ID 1H5R complex structure, in its supposed bioactive conformation used here as a query/template for the virtual screening studies.

Virtual screening studies

LBVS was the first virtual screening here performed. We use the ROCS (73) and EON (74) software to carry out three-dimensional similarity studies (of shape and electrostatic potential, respectively). After LBVS, SBVS studies were then performed and, thus, the resulting compounds were screened according to the scores obtained in the docking simulations performed using the GOLD software.

Molecules were evaluated regarding their ADME/Tox properties, using the QikProp (75) (from the Schroedinger company) and DEREK (76) (from the Lhasa company) software, respectively.

The “surviving” compounds to the ADME/Tox filter were then submitted to pharmacokinetic analyses performed using QikProp and toxicological analysis performed using DEREK. Finally, for final selection of the compounds, a visual inspection of the interaction/binding modes of these compounds inside the XanB catalytic site was performed.

XanB enzymatic activities and in vitro inhibition by the in silico selected compounds

The PMI activity of the recombinant XanB was first assessed by Seliwanoff’s test (77, 78). Briefly, 30 µg of recombinant XanB, D-mannose-6-phosphate at 0.5 mM, and Seliwanoff reagent were added, and results were photographed. The enzyme was replaced by the buffer for the negative control, and fructose-6-phosphate was used instead of D-mannose-6-phosphate at the same concentration of 0.5 mM for the positive control. Tests were performed in triplicate. A second method involving the coupling of three enzymatic reactions (79) was used by quantifying NAPDH formation at 340 nm. The reaction consisted of recombinant XanB 4 ng/µL, mannose-6-phosphate 10 mM, PGI 0.06 U/µL, G6PD 0.06 U/µL, NADP +40 mM, and MgCl2 500 mM (80). The negative control replaced XanB by buffer, while the positive control had fructose-6-phosphate 10 mM instead of mannose-6-phosphate. Triplicate reactions were monitored at 340 nm every 30 seconds. Mean absorbance and standard deviation were calculated. Inhibitors were tested at 1 mM using the same conditions.

GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase activity of XanB was tested by the method of Davis et al. (81) by conversion of mannose-1-phosphate and GTP into GDP-mannose and pyrophosphate, coupled with pyrophosphatase, which converts pyrophosphate into inorganic phosphate (absorption at 650 nm). Briefly, reaction was composed of XanB 20 ng/µL, D-mannose-1-phosphate 1 mM, GTP 1 mM, MgCl2 500 mM, pyrophosphatase 0.01 U/µL, and dithiothreitol (DTT) 100 mM. For the negative control, XanB was replaced by buffer. Reactions were performed in triplicate, and pyrophosphate detection was performed using a reagent containing malachite green, ammonium molybdate, and Triton in HCl. Absorbance at 650 nm was measured, and the mean absorbance and standard deviation were calculated. For the inhibition tests, the same conditions were repeated, but XanB was incubated with inhibitors at 1 mM for 30 minutes at 30°C.

In vivo pathogenicity assays of Xcc in Citrus spp. in presence of XanB inhibitors

The protective effect of XanB inhibitors was assessed in C. aurantifolia and C. sinensis. Each treatment consisted of three plants, with 10 leaves per plant. Inhibitors were sprayed at a concentration of 1 mM on the adaxial and abaxial surfaces of the leaves. In the assay with C. sinensis, copper was applied at 1.08 g/L, which was the same as the field application rate (3). Twenty-four hours after inhibitor application, the plants were spray-inoculated with a Xcc suspension on both surfaces of the leaves and placed in a humid chamber for 24 h. Evaluation of the 10 leaves of each plant was conducted using ImageJ software.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Célia Regina Câmara for the technical assistance (LBBMA-UFSCar).

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–Brasil–Finance Code 001 (A.V.A. grant number 88882.426495/2019–01) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (Programa Jovem Pesquisador Proc. 07/50910-2, and Auxílio à Pesquisa Proc. 2020/05529-3).

M.T.M.N.-M. proposed the Xanthomonas citri target protein for this study, coordinated collaborative interaction among most research groups, was A.V.A.’s doctoral advisor, and idealized with A.V.A. most of the genetics assays and in vitro experiments. C.H.T.P.S. idealized, supervised, and coordinated most of the in silico experiments and was M.P.B.'s advisor and L.B.F.’s supervisor. A.V.A. performed the construction of the xanB deleted mutant and complemented strains, and idealized and performed motility, biofilm, and UV resistance assays for both strains. A.V.A. performed the xanB gene cloning, recombinant expression, and purification with the participation of C.H.A.M., who was supervised by A.V.A. L.B.C. performed preliminary pathogenicity tests on Citrus spp. for the xanB deletion mutant, under H.F.'s supervision. A.V.A. and T.G.S. performed most of the in vivo experiments with the mutant and complemented strains, and also the in vivo assays with the inhibitors under F.B.'s coordination and supervision. In vitro enzymatic assays and in vitro inhibition tests were performed by A.V.A. M.P.B. contributed in part with in vitro inhibition assays and with homology modeling and some virtual screening experiments, whereas L.B.F. continued with some other virtual screening experiments. The original draft of the manuscript was written by A.V.A. and M.P.B. Manuscript review and editing were performed by A.V.A., F.B., L.B.F., and M.P.B. under continuous interactive revision by M.T.M.N.-M. and C.H.T.P.S. C.A.T. provided oversight as well as critical review of the paper. All authors read and agreed on the submitted version of the manuscript and declared no conflict of interest.

This work has generated the patent BR 102021008663-7 A2 ("Uso de compostos químicos inibidores da fosfomanose isomerase para controle do cancro cítrico e fitopatologias associadas ao gênero Xanthomonas"), deposited at the Instituto Nacional da Propriedade Industrial (INPI- Brazil, https://www.gov.br/inpi/pt-br) on 4 May 2021, published by INPI on 16 November 2022 and licensed in December 2022.

Contributor Information

Carlos Henrique Tomich de Paula Silva, Email: tomich@fcfrp.usp.br.

Maria Teresa Marques Novo-Mansur, Email: marinovo@ufscar.br.

Lindsey Price Burbank, USDA - San Joaquin Valley Agricultural Sciences Center, Parlier, California, USA.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data are available in the paper or in the supplemental material.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.03673-23.

Additional experimental details, Figures S1 to S7, and Table S1.

Additional text for Material and Methods.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Naqvi SAH, Wang J, Malik MT, Umar U-U-D Ateeq-Ur-RehmanHasnain A, Sohail MA, Shakeel MT, Nauman M Hafeez-ur-RehmanHassan MZ, Fatima M, Datta R. 2022. Citrus canker—distribution, taxonomy, epidemiology, disease cycle, pathogen biology, detection, and management: a critical review and future research agenda. Agronomy 12:1075. doi: 10.3390/agronomy12051075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Behlau F, Barelli NL, Belasque J. 2014. Lessons from a case of successful eradication of citrus canker in a citrus-producing farm in São Paulo state, Brazil. Plant Pathol J 96:561–568. doi: 10.4454/JPP.V96I3.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Behlau F, Lanza FE, da Silva Scapin M, Scandelai LHM, Silva Junior GJ. 2021. Spray volume and rate based on the tree row volume for a sustainable use of copper in the control of citrus canker. Plant Dis 105:183–192. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-12-19-2673-RE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ference CM, Gochez AM, Behlau F, Wang N, Graham JH, Jones JB. 2018. Recent advances in the understanding of Xanthomonas Citri ssp. citri pathogenesis and citrus canker disease management. Mol Plant Pathol 19:1302–1318. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carnielli CM, Artier J, de Oliveira JCF, Novo-Mansur MTM. 2017. Xanthomonas Citri subsp. citri surface proteome by 2D-DIGE: ferric enterobactin receptor and other outer membrane proteins potentially involved in citric host interaction. J Proteomics 151:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Papoutsopoulou SV, Kyriakidis DA. 1997. Phosphomannose isomerase of Xanthomonas campestris: a zinc activated enzyme. Mol Cell Biochem 177:183–191. doi: 10.1023/a:1006825825681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wiederschain GYa. 2013. Glycobiology: progress, problems, and perspectives. Biochemistry (Moscow) 78:679–696. doi: 10.1134/S0006297913070018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gao H, Yu Y, Leary JA. 2005. Mechanism and kinetics of metalloenzyme phosphomannose isomerase: measurement of dissociation constants and effect of zinc binding using ESI-FTICR mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 77:5596–5603. doi: 10.1021/ac050549m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jensen SO, Reeves PR. 1998. Domain organisation in phosphomannose isomerases (types I and II). Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology 1382:5–7. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4838(97)00122-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. da Silva ACR, Ferro JA, Reinach FC, Farah CS, Furlan LR, Quaggio RB, Monteiro-Vitorello CB, Van Sluys MA, Almeida NF, Alves LMC, et al. 2002. Comparison of the genomes of two Xanthomonas pathogens with differing host Specificities. Nature 417:459–463. doi: 10.1038/417459a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cleasby A, Wonacott A, Skarzynski T, Hubbard RE, Davies GJ, Proudfoot AE, Bernard AR, Payton MA, Wells TN. 1996. The X-ray crystal structure of phosphomannose isomerase from Candida albicans at 1.7 angstrom resolution. Nat Struct Biol 3:470–479. doi: 10.1038/nsb0596-470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patterson JH, Waller RF, Jeevarajah D, Billman-Jacobe H, McConville MJ. 2003. Mannose metabolism is required for mycobacterial growth. Biochem J 372:77–86. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Garami A, Ilg T. 2001. Disruption of mannose activation in Leishmania mexicana: GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase is required for virulence, but not for viability. EMBO J 20:3657–3666. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.14.3657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Federico LB, Barcelos MP, Silva GM, Francischini IAG, Taft CA, da Silva CHT de P. 2021. Key aspects for achieving hits by virtual screening studies, p 455–487. In

- 15. B MP, F LB, T CA, C.H.T de P da S. 2020. Prediction of the three-dimensional structure of phosphate-6-mannose PMI present in the cell membrane of Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri of interest for the citrus canker control, p 259–276. In Emerging research in science and engineering based on advanced experimental and computational strategies. Engineering materials. Springer, Cham. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rollinger JM, Stuppner H, Langer T. 2008. Virtual screening for the discovery of bioactive natural products, p 211–249. In Natural compounds as drugs volume I. Birkhäuser Basel, Basel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McInnes C. 2007. Virtual screening strategies in drug discovery. Curr Opin Chem Biol 11:494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Santana K, do Nascimento LD, Lima E Lima A, Damasceno V, Nahum C, Braga RC, Lameira J. 2021. Applications of virtual screening in bioprospecting: facts, shifts, and perspectives to explore the chemo-structural diversity of natural products. Front Chem 9:662688. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.662688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hamza A, Wei N-N, Zhan C-G. 2012. Ligand-based virtual screening approach using a new scoring function. J Chem Inf Model 52:963–974. doi: 10.1021/ci200617d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kroemer RT. 2007. Structure-based drug design: docking and scoring. Curr Protein Pept Sci 8:312–328. doi: 10.2174/138920307781369382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cavasotto CN, Orry AJW. 2007. Ligand docking and structure-based virtual screening in drug discovery. Curr Top Med Chem 7:1006–1014. doi: 10.2174/156802607780906753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sliwoski G, Kothiwale S, Meiler J, Lowe EW. 2014. Computational methods in drug discovery. Pharmacol Rev 66:334–395. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.007336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alexandrino AV, Prieto EL, Nicolela NCS, da Silva Marin TG, dos Santos TA, de Oliveira da Silva JPM, da Cunha AF, Behlau F, Novo-Mansur MTM. 2023. Xylose isomerase depletion enhances virulence of Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri in Citrus aurantifolia. Int J Mol Sci 24:11491. doi: 10.3390/ijms241411491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. National center for biotechnology information; National library of medicine (US). 1988. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)[Internet]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- 25. Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Söding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. 2011. Fast, sscalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol 7:1–6. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cole JC, Murray CW, Nissink JWM, Taylor RD, Taylor R. 2005. Comparing protein-ligand docking programs is difficult. Proteins: Struct Funct Genet 60:325–332. doi: 10.1002/prot.20497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bursulaya BD, Totrov M, Abagyan R, Brooks CL. 2003. Comparative study of several algorithms for flexible ligand docking. J Comput Aided Mol Des 17:755–763. doi: 10.1023/b:jcam.0000017496.76572.6f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vieth M, Hirst JD, Kolinski A, Brooks CL. 1998. Assessing energy functions for flexible docking. J Comput Chem 19:1612–1622. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Empereur-Mot C, Zagury JF, Montes M. 2016. Screening explorer-an interactive tool for the analysis of screening results. J Chem Inf Model 56:2281–2286. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Empereur-Mot C, Guillemain H, Latouche A, Zagury JF, Viallon V, Montes M. 2015. Predictiveness curves in virtual screening. J Cheminform 7:52. doi: 10.1186/s13321-015-0100-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu T, Lin Y, Wen X, Jorissen RN, Gilson MK. 2007. BindingDB: a web-accessible database of experimentally determined protein-ligand binding affinities. Nucleic Acids Res 35:D198–201. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Andrade AE, Silva LP, Pereira JL, Noronha EF, Reis FB, Bloch C, dos Santos MF, Domont GB, Franco OL, Mehta A. 2008. In vivo proteome analysis of Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris in the interaction with the host plant Brassica oleracea. FEMS Microbiol Lett 281:167–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01090.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goto LS, Vessoni Alexandrino A, Malvessi Pereira C, Silva Martins C, D’Muniz Pereira H, Brandão-Neto J, Marques Novo-Mansur MT. 2016. Structural and functional characterization of the phosphoglucomutase from Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics 1864:1658–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Petrocelli S, Tondo ML, Daurelio LD, Orellano EG. 2012. Modifications of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri lipopolysaccharide affect the basal response and the virulence process during citrus canker. PLoS One 7:e40051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Picchi SC, Granato LM, Franzini MJF, Andrade MO, Takita MA, Machado MA, de Souza AA. 2021. Modified monosaccharides content of xanthan gum impairs citrus canker disease by affecting the epiphytic lifestyle of Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. Microorganisms 9:1176. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9061176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Baptista JC, Machado MA, Homem RA, Torres PS, Vojnov AA, do Amaral AM. 2010. Mutation in the xpsD gene of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri affects cellulose degradation and virulence. Genet Mol Biol 33:146–153. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572009005000110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Conforte VP, Malamud F, Yaryura PM, Toum Terrones L, Torres PS, De Pino V, Chazarreta CN, Gudesblat GE, Castagnaro AP, R Marano M, Vojnov AA. 2019. The histone‐Like protein HupB influences biofilm formation and virulence in Xanthomonas citri ssp. citri through the regulation of flagellar biosynthesis. Mol Plant Pathol 20:589–598. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Baránek M, Kováčová V, Gazdík F, Špetík M, Eichmeier A, Puławska J, Baránková K. 2021. Epigenetic modulating chemicals significantly affect the virulence and genetic characteristics of the bacterial plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Genes (Basel) 12:804. doi: 10.3390/genes12060804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Meyer A, Pühler A, Niehaus K. 2001. The lipopolysaccharides of the phytopathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris induce an oxidative burst reaction in cell cultures of Nicotiana tabacum. Planta 213:214–222. doi: 10.1007/s004250000493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Newman MA, Daniels MJ, Dow JM. 1995. Lipopolysaccharide from Xanthomonas campestris induces defense-related gene expression in Brassica campestris. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 8:778–780. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-8-0778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wanke A, Malisic M, Wawra S, Zuccaro A. 2021. Unraveling the sugar code: the role of microbial extracellular glycans in plant–microbe interactions. J Exp Bot 72:15–35. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eraa414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ren H, Zhao X, Li W, Hussain J, Qi G, Liu S. 2021. Calcium signaling in plant programmed cell death. Cells 10:1089. doi: 10.3390/cells10051089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Braun SG, Meyer A, Holst O, Pühler A, Niehaus K. 2005. Characterization of the Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris lipopolysaccharide substructures essential for elicitation of an oxidative burst in tobacco cells. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 18:674–681. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-0674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Huang T-P, Somers EB, Wong ACL. 2006. Differential biofilm formation and motility associated with lipopolysaccharide/exopolysaccharide-coupled biosynthetic genes in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. J Bacteriol 188:3116–3120. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.8.3116-3120.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Harshey RM. 2003. Bacterial motility on a surface: many ways to a common goal. Annu Rev Microbiol 57:249–273. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.091014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Graham JH, Gottwald TR, Cubero J, Achor DS. 2004. Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri: factors affecting successful erradication of citrus canker. Mol Plant Pathol 5:1–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2004.00197.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li J, Wang N. 2011. The wxacO gene of Xanthomonas citri ssp. citri encodes a protein with a role in lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis, biofilm formation, stress tolerance and virulence. Mol Plant Pathol 12:381–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00681.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Flemming H-C, Wingender J. 2010. The biofilm matrix. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:623–633. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Li J, Wang N. 2011. Genome-wide mutagenesis of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri reveals novel genetic determinants and regulation mechanisms of biofilm formation. . PLoS One 6:e21804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Donlan RM. 2002. Biofilms: microbial life on surfaces. Emerg Infect Dis 8:881–890. doi: 10.3201/eid0809.020063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rigano LA, Siciliano F, Enrique R, Sendín L, Filippone P, Torres PS, Qüesta J, Dow JM, Castagnaro AP, Vojnov AA, Marano MR. 2007. Biofilm formation, epiphytic fitness, and canker development in Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 20:1222–1230. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-10-1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Karatan E, Watnick P. 2009. Signals, regulatory networks, and materials that build and break bacterial biofilms. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73:310–347. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00041-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Meyer DF, Bogdanove AJ. 2009. Genomics-driven advances in Xanthomonas biology. Plant pathogenic bacteria: genomics and molecular Biology 147:161. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jiang H, Ouyang H, Zhou H, Jin C. 2008. GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase is essential for cell wall integrity, morphogenesis and viability of Aspergillus fumigatus. Microbiology (Reading) 154:2730–2739. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/019240-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Salinas SR, Bianco MI, Barreras M, Ielpi L. 2011. Expression, purification and biochemical characterization of GumI, a monotopic membrane GDP-mannose:glycolipid 4 - D-mannosyltransferase from Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Glycobiology 21:903–913. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwr022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Artier J, da Silva Zandonadi F, de Souza Carvalho FM, Pauletti BA, Leme AFP, Carnielli CM, Selistre-de-Araujo HS, Bertolini MC, Ferro JA, Belasque Júnior J, de Oliveira JCF, Novo-Mansur MTM. 2018. Comparative proteomic analysis of Xanthomonas citri ssp. citri periplasmic proteins reveals changes in cellular envelope metabolism during in vitro pathogenicity induction. Mol Plant Pathol 19:143–157. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ausubel FM. 2002. Short protocols in molecular biology: a compendium of methods from current protocols in molecular. Biology5th ed. Wiley, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Alexandrino AV, Goto LS, Novo-Mansur MTM. 2016. TreA codifies for a trehalase with involvement in Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri pathogenicity. PLoS One 11:e0162886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cabrejos DAL, Alexandrino AV, Pereira CM, Mendonça DC, Pereira HD, Novo-Mansur MTM, Garratt RC, Goto LS. 2019. Structural characterization of a pathogenicity-related superoxide dismutase codified by a probably essential gene in Xanthomonas citri subsp. PLoS One 14:e0209988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ferreira H, Barrientos FJA, Baldini RL, Rosato YB. 1995. Electrotransformation of three pathovars of Xanthomonas campestris. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 43:651–655. doi: 10.1007/BF00164769 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Malamud F, Torres PS, Roeschlin R, Rigano LA, Enrique R, Bonomi HR, Castagnaro AP, Marano MR, Vojnov AA. 2011. The Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri flagellum is required for mature biofilm and canker development. Microbiology (Reading) 157:819–829. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.044255-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Laemmli UK. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Webb B, Sali A. 2016. Comparative protein structure modeling using MODELLER. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 54:5. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vriend G. 1990. WHAT IF: a molecular modeling and drug design program. J Mol Graph 8:52–56. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(90)80070-v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Irwin JJ, Shoichet BK. 2005. ZINC − A free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening ZINC - a free database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. J Chem Inf Model 45:177–182. doi: 10.1021/ci049714+ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sterling T, Irwin JJ. 2015. ZINC 15 - ligand discovery for everyone. J Chem Inf Model 55:2324–2337. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chen X, Liu M, Gilson MK. 2001. BindingDB: a web-accesible molecular recognition database. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen 4:719–725. doi: 10.2174/1386207013330670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. ChemBridge . 2018. The Glod standard in small molecule screening libraries and building blocks

- 70. Maybridge . 2004. The Maybridge screening collection. Screening Guide. Available from: http://www.maybridge.com

- 71. Boström J, Greenwood JR, Gottfries J. 2003. Assessing the performance of OMEGA with respect to retrieving bioactive conformations. J Mol Graph Model 21:449–462. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(02)00204-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. da Silva CHT de P, Taft CA. 2017. 3d descriptors calculation and conformational search to investigate potential bioactive conformations, with application in 3d-QSAR and virtual screening in drug design. J Biomol Struct Dyn 35:2966–2974. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2016.1237382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Openeye scientific software . 2018. Rocs 3.4.0.4. Santa Fe.

- 74. Openeye scientific software . 2018. Eon 2.3.1.2. 2.2.0.5. Santa Fe, New Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Schrodinger L. 2021. QikProp: rapid ADME predictions of drug candidates. https://www.schrodinger.com/qikprop.

- 76. Marchant CA, Briggs KA, Long A. 2008. In silico tools for sharing data and knowledge on toxicity and metabolism: derek for windows, meteor, and vitic. Toxicol Mech Methods 18:177–187. doi: 10.1080/15376510701857320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Chawla R. 2014. Practical clinical biochemistry: methods and interpretations. JP Medical Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Roe JH. 1934. A colorimetric method for the determination of fructose in blood and urine. J Biol Chem 107:15–22. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)75382-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gracy RW, Noltmann EA. 1968. Studies on Phosphomannose isomerase I. isolation, homogeneity measurements, and determination of some physical properties. J Biol Chem 243:3161–3168. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)93391-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wu B, Zhang Y, Zheng R, Guo C, Wang PG. 2002. Bifunctional phosphomannose isomerase/GDPGDP- D -mannose pyrophosphorylase is the point of control for GDP- D -mannose biosynthesis in Helicobacter pylori. FEBS Lett 519:87–92. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)02717-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Davis AJ, Perugini MA, Smith BJ, Stewart JD, Ilg T, Hodder AN, Handman E. 2004. Properties of GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase, a critical enzyme and drug target in Leishmania mexicana. J Biol Chem 279:12462–12468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312365200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional experimental details, Figures S1 to S7, and Table S1.

Additional text for Material and Methods.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the paper or in the supplemental material.