Abstract

Background

Finding individuals with drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) is important to control the pandemic and improve patient clinical outcomes. To our knowledge, systematic reviews assessing the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of different DR-TB case-finding strategies to inform research, policy, and practice, have not been conducted and the scope of primary research is unknown.

Objective

We therefore assessed the available literature on DR-TB case-finding strategies.

Methods

We looked at systematic reviews, trials, qualitative studies, diagnostic test accuracy studies, and other primary research that sought to improve DR-TB case detection specifically. We excluded studies that included patients seeking care for tuberculosis (TB) symptoms, patients already diagnosed with TB, or were laboratory-based. We searched the academic databases of MEDLINE, Embase, The Cochrane Library, Africa-Wide Information, CINAHL (Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Epistemonikos, and PROSPERO (The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) using no language or date restrictions. We screened titles, abstracts, and full-text articles in duplicate. Data extraction and analyses were carried out in Excel (Microsoft Corp).

Results

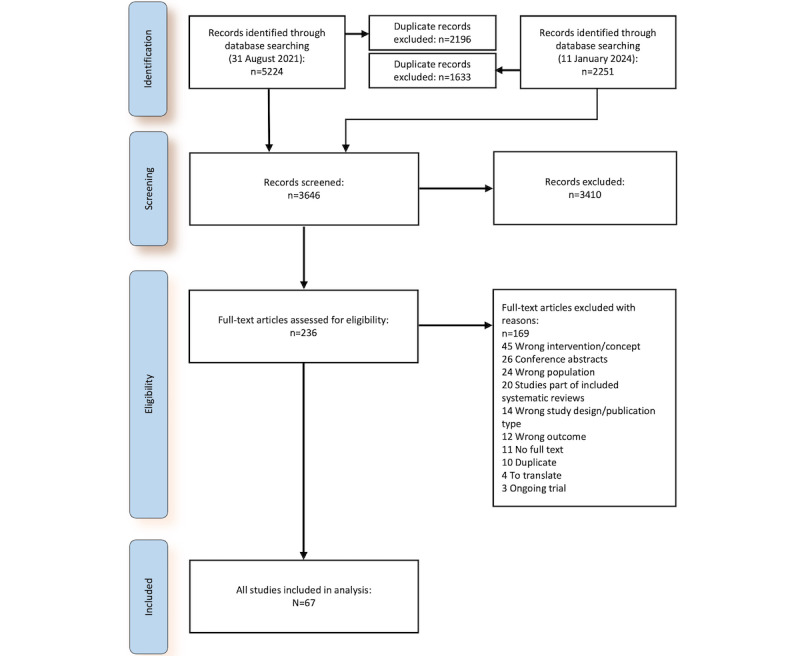

We screened 3646 titles and abstracts and 236 full-text articles. We identified 6 systematic reviews and 61 primary studies. Five reviews described the yield of contact investigation and focused on household contacts, airline contacts, comparison between drug-susceptible tuberculosis and DR-TB contacts, and concordance of DR-TB profiles between index cases and contacts. One review compared universal versus selective drug resistance testing. Primary studies described (1) 34 contact investigations, (2) 17 outbreak investigations, (3) 3 airline contact investigations, (4) 5 epidemiological analyses, (5) 1 public-private partnership program, and (6) an e-registry program. Primary studies were all descriptive and included cross-sectional and retrospective reviews of program data. No trials were identified. Data extraction from contact investigations was difficult due to incomplete reporting of relevant information.

Conclusions

Existing descriptive reviews can be updated, but there is a dearth of knowledge on the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of DR-TB case-finding strategies to inform policy and practice. There is also a need for standardization of terminology, design, and reporting of DR-TB case-finding studies.

Keywords: tuberculosis, drug-resistant tuberculosis, drug-resistant tuberculosis case finding, drug-resistant tuberculosis case detection, drug-resistant tuberculosis screening, drug-resistant tuberculosis contact investigation, scoping review, TB symptom, anti-tuberculosis drug, strategies, multidrug-resistant, systematic review, drug resistant, drug resistance, medication, tuberculosis, diagnosis, screening

Introduction

With the emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains resistant to first-line antituberculosis drugs, strategies to control tuberculosis (TB) have become even more challenging [1]. It is estimated that almost half a million people developed rifampicin-resistant TB, of which 78% had multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in 2019 [2]. Although drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) is not as prevalent as drug-susceptible tuberculosis (DS-TB), it is more difficult to diagnose, treatment is longer and more toxic, outcomes are worse, and costs are higher.

Finding individuals with DR-TB and initiating treatment as early as possible is important to improve patient clinical outcomes and to break the chain of transmission to help control the pandemic. Despite new diagnostic technologies, only a third of the estimated number of people who developed DR-TB initiated treatment in 2020 [3].

TB can be detected after the patient presents passively to health services or follows one of several different screening pathways depending on the case-finding strategy of a TB program [4]. Pathways can also be enhanced through several activities such as health promotion in the community, improved access to TB diagnostic services, or training of health workers to identify presumptive TB at general health services. Multiple activities often result in complex interventions and heterogeneous trials that are difficult to meta-analyze in systematic reviews [5,6].

To our knowledge, systematic reviews assessing the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of different DR-TB case-finding strategies to inform research, policy, and practice, have not been conducted and it is unknown whether enough research exists to conduct such reviews. It is also unknown whether case-finding strategies are similar for DR-TB and DS-TB and whether we can draw on findings from DS-TB reviews to inform decisions on DR-TB case-finding strategies.

Scoping reviews are useful for scoping the literature and to clarify concepts [7,8]. We therefore conducted a scoping review to assess whether enough research exists for a systematic review, to identify priority questions for such a review, and to clarify which case-finding strategies exist for DR-TB specifically.

Methods

Reporting Guidelines and Protocol

The Arksey and O’Malley framework [9], Levac et al [10], and the Joanna Briggs Institute scoping review methodology [8] guided methods for this scoping review. The review is reported according to the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) [11]. See Multimedia Appendix 1 for the completed PRISMA-ScR checklist. The protocol for this review was published in JMIR Research Protocols [12].

Defining the Research Question

The question for our review was, what literature is available on DR-TB case finding and which case-finding strategies are described? We looked at studies that had sought to improve DR-TB case detection.

Eligibility Criteria

Textbox 1 lists the inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants, concept, outcome, context, and study design.

Eligibility criteria.

Inclusion criteria

Participants

Participate regardless of symptoms, for example, contacts, people living with HIV attending HIV care, whole communities

Concept/Intervention

Strategies aiming to improve or enhance participants’ pathways to drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) case detection specifically

Outcome

Patients diagnosed with tuberculosis (TB)

Context

Community

Primary, secondary, or tertiary care

Study design

Primary studies

Systematic reviews

Qualitative studies, where the experiences of individuals who receive the intervention or those who provide the intervention are investigated

Studies of diagnostic test accuracy if the study describes a DR-TB screening strategy

Trials comparing different screening or diagnostic tools within a DR-TB case-finding intervention

Exclusion criteria

Participants

Patients with TB symptoms seeking care

Patients diagnosed with TB

Laboratory samples/isolates

Concept/Intervention

Intervention strategies aiming to improve TB case finding in general, even if they do report the yield of people with DR-TB

Outcome

No report of patients diagnosed with TB

Context

Laboratory based

Study design

Meta-reviews (review of reviews)

Narrative reviews

Editorials

Opinion articles

Meeting summaries

Guidelines

Prevalence surveys, except if the survey includes an intervention strategy to find individuals with DR-TB specifically

Conference abstracts

Identifying Relevant Studies

With assistance from an information specialist, we searched the academic databases of MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase (Ovid), The Cochrane Library, Africa-Wide Information (EBSCOhost), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), Epistemonikos, and PROSPERO (The International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) using no language or date restrictions. These searches were conducted on August 31, 2021, and after an initial peer review of this article, an updated search was conducted on January 11, 2024.

The search string included combinations of the following 3 domains, that are (1) terms related to “TB”; (2) terms related to “drug resistance”; and (3) terms related to “case finding,” “case detection,” “screening,” “contact investigation,” and “contact tracing.”

Search strategies from each electronic database are detailed per search date in Multimedia Appendix 2.

Study Selection

We used Rayyan systematic review software [13] to screen titles, abstracts, and full-text articles. Decisions were blinded, except when reviewing conflicts. Reviewers screened abstracts in duplicate for inclusion. Conflicts were resolved through discussion. Full-text articles were also screened in duplicate. Disagreements were resolved through discussion to determine final inclusion.

Charting the Data

We developed a data extraction form in Excel (Microsoft Corp). The data extraction form was applied to all primary research reports to collect standard information on each study. Textbox 2 lists the information that was collected.

Information collected on each study.

Authors, journal, year of publication

Aim or purpose of the research

Study design

Country

Income

Tuberculosis prevalence

HIV prevalence

Urban or rural setting

Participants

Age

Sex

HIV status

Other reported risk factors

Target group and how the group was identified if applicable

Interventions

All components (activities) of the intervention

Types of providers

Screening and diagnostic tools used

Treatment support, including preventive therapy

Outcomes assessed

One reviewer extracted data from included papers and a second reviewer (SSvW) checked the extracted data. Reviewers met regularly to determine whether their approach was consistent and in line with the research question.

Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

We provide a narrative report with supporting tables to summarize the data. Table 1 contains definitions we used in charting, collating, summarizing, and reporting our results.

Table 1.

Definitions.

| Terms | Definitions |

| DR-TBa | All types of DR-TB that include DR-TB with resistance to one first-line drug, MDR-TBb, XDR-TBc, and any other DR-TB reported by the authors. |

| Systematic screening for TBd disease | “The systematic identification of people with suspected (presumptive) TB disease, in a predetermined target group, using tests, examinations, or other procedures that can be applied rapidly. Among those screened positive, the diagnosis needs to be established by one or several diagnostic tests and additional clinical assessments, which together have high accuracy.” [14] |

| A screening tool | Tests, examinations, or other procedures used for systematic screening for TB disease. Examples of TB screening tools include a structured symptom-based questionnaire, CXRe, or an algorithm [4]. Algorithms may include sequential or parallel tests. With sequential tests, only those who screen positive with the initial test receive a second test. With parallel tests, those who screen positive on any of the tests are regarded as screen positives. |

| A diagnostic tool | Tests, examinations, or other procedures used to establish a diagnosis of TB disease in people identified with presumptive TB. Examples of TB diagnostic tools include a clinical algorithm, sputum smear microscopy, Xpert MTB/RIF (Cepheid Inc), or culture [4]. |

| TB symptom | Any TB symptom, for example, cough, fever, night sweats, weight loss, or combination of TB symptoms as defined by the study authors. |

| Care seeking | People seeking care for a perceived health problem. |

| TB care seeking | People seeking care for TB symptoms specifically. |

| A risk group | Any group of people in whom the prevalence or incidence of TB is significantly higher than in the general population. Examples of risk groups include a whole population within a geographical area or TB contacts [15]. |

| A clinical risk group | Individuals diagnosed with a specific disease or condition that increases their risk for TB, for example, people living with HIV (PLHIV). |

| Presumptive TB | Presumptive TB is identified when a provider identifies a patient with suspected TB disease. In the context of screening, a person who screens positive is a patient with presumptive TB. |

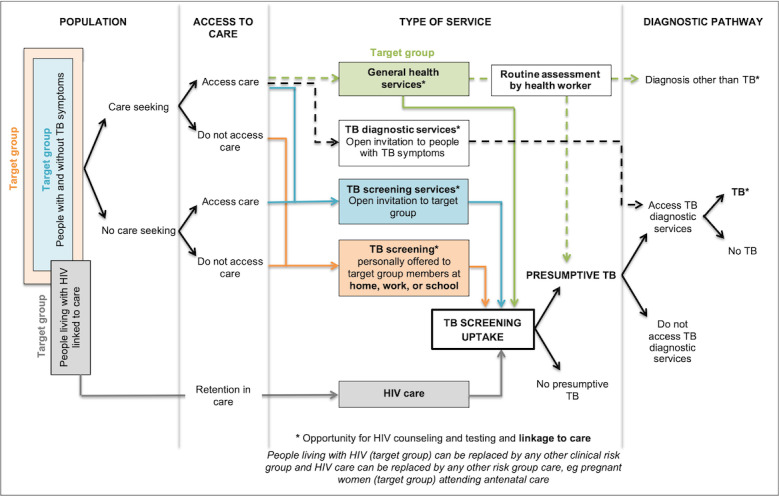

| Passive case finding | Care-seeking pathway without TB screening, that is, the green and black dashed pathways in Figure 1 [16]. |

| Passive case finding with an element of systematic screening or triage | TB screening at general health services, that is, the green pathway in Figure 1. |

| Enhanced case finding | TB health promotion with or without TB screening. |

| Active case finding | TB screening at TB screening services or at home, work, or school, that is, the blue and orange pathways in Figure 1. If the target group is TB contacts, this can also be referred to contact tracing or contact investigation. |

| Intensified case finding | TB screening of a clinical risk group, for example, people living with HIV (ie, the gray pathway in Figure 1). |

aDR-TB: drug-resistant tuberculosis.

bMDR-TB: multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

cXDR-TB: extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis.

dTB: tuberculosis.

eCXR: chest radiography.

A systems-based logic model developed from a synthesis of DS-TB case-finding strategies (Figure 1) was used as a framework to describe different strategies and resulting pathways (care-seeking pathways or screening pathways).

Figure 1.

A systems-based logic model depicting types of services and associated pathways to tuberculosis (TB) case detection [16].

Quality appraisal was not conducted, because this is a scoping review and our interest is in the existing evidence base, regardless of study design and quality.

Results

Overview of the Available Literature

We screened 3646 titles and abstracts and 236 full-text articles. We identified 6 systematic reviews and 61 primary studies (Figure 2) for inclusion. We divided primary studies into 6 different categories (themes) and described each category in more detail below. Table 2 gives an overview of the categories and references to further detail.

Figure 2.

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram.

Table 2.

Overview of categories into which included studies were divided.

| Type of study | Articles | Further detail | ||

| Systematic reviews | n=6 | Table 3 | ||

| Primary studies (N=61) | ||||

|

|

Close- or household-contact investigations | n=34 (56%) | Multimedia Appendix 3 and Table 4 | |

|

|

Outbreak investigations | n=17 (28%) | Table 5 | |

|

|

Airline contact investigations | n=3 (5%) |

|

|

|

|

Epidemiological analyses | n=5 (8%) |

|

|

|

|

Public-private partnership program | n=1 (2%) |

|

|

|

|

E-registry program | n=1 (2%) |

|

|

Systematic Reviews

We identified 6 systematic reviews. Outcomes were descriptive and none of the reviews identified any randomized controlled trials. In 5 of the 6 reviews, the date of the last search was more than 5 years ago (Table 3). In reviews with the yield of TB disease as an outcome, the denominator was reported as the number of contacts evaluated or screened; however, specific definitions for “evaluated” or “screened” were not reported and the yield for a specific screening or diagnostic strategy is unknown.

Table 3.

Overview of the included systematic reviews.

| Review | Primary outcome | Date of last search |

| Abubakar [17] | Number of contacts screened, and number of individuals with TBa infection and TB disease identified | November 2009 |

| Fox et al [18] | Yield of TB disease and TB infection for both DS-TBb and DR-TBc source cases | October 2011 |

| Shah et al [19] | Yield of TB infection and TB disease in contacts of DR-TB source cases | December 2011 |

| Kodama et al [20] | Relative risk ratio of TB disease in DS-TB contacts compared with DR-TB contacts | Not reported |

| Svadzian et al [21] | Proportion of cases from those evaluated through universal testing (all individuals in the study received DSTd) and those evaluated through selective testing (only the high-risk group received DST) | June 2019 |

| Chiang et al [22] | Percentage of secondary cases whose Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains were resistant to the same drugs as strains from the index cases | July 2018 |

aTB: tuberculosis.

bDS-TB: drug-susceptible tuberculosis.

cDR-TB: drug-resistant tuberculosis.

dDST: drug-susceptibility testing.

Primary Studies

We identified 61 primary studies that were not included in any of the above reviews. Primary studies were descriptive and included cross-sectional studies, prospective studies, and retrospective reviews of program data. No trials were identified. Thirty-four studies were close-contact or household-contact investigations, 17 were outbreak investigations, 3 were airline contact investigations, 5 were epidemiological analyses, 1 described a private-public partnership program, and 1 assessed the feasibility and acceptability of an e-registry program (Table 2). Case-finding pathways were seldom described clearly, for example, whether contacts were invited for screening regardless of symptoms (Figure 1, blue pathway), whether all contacts were screened for TB at home (Figure 1, orange pathway), or whether those who experienced TB symptoms were invited for further tests (Figure 1, black dashed pathway).

Close-Contact or Household-Contact Investigations

Countries where contact investigations were conducted included South Africa (n=6), India (n=5), Pakistan (n=4), Australia (n=2), the United States (n=1), Ethiopia (n=2), Myanmar (n=2), Thailand (n=1), France (n=1), Vietnam (n=1), Papua New Guinea (n=1), Armenia (n=1), the United Kingdom (n=1), Spain (n=1), South Korea (n=1), Oman (n=1), and Tajikistan (n=1). Two multicountry studies were conducted in Botswana, Brazil, Haiti, Kenya, Peru, South Africa, and Thailand. Data extraction from contact investigations was difficult due to incomplete reporting of relevant information, such as the total number of source cases or the number of cases tested for drug susceptibility (Table 4). Screening and diagnostic tools were not well reported and often lacked consistent or standardized use. Although investigations focused on contacts who had been exposed to DR-TB, drug-susceptibility testing (DST) was seldom reported. Case-finding pathways were also not clearly described. Some contacts were followed up over 1-2 years and some were only evaluated at baseline. Lack of or inconsistent reporting of this relevant data results in an unknown or inconsistent denominator when calculating the yield of screening the contacts of individuals with TB and makes it challenging to pool results or compare different case-finding strategies. There was also little consistency in the use of definitions. Source cases were often defined as “registered MDR-TB or extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB) cases” without knowledge of how they were diagnosed. Several different definitions for “close contact” or “household contact” were reported. Some definitions were broad, for example, “people living with or having regular daily interaction with the MDR-TB source case” [23], while other definitions were more specific, for example, “a person who had shared the same enclosed living space for one or more nights a week, or for frequent or extended periods of time during the day, with the index patient during the 3 months before the current treatment episode began” [24-26]. The latter definition was used more often. See Multimedia Appendix 3 for more details.

Table 4.

Data from DR-TBa contact investigation studies.

| Study | Source/Index cases | Contacts | Screening | TBb diagnosis | DS-TBc diagnosis | DR-TB diagnosis | |||||||||

|

|

Total identified | Studied | Total identified | Screened | Positive screen | Evaluated | Total TB | Diagnosed | Evaluated | Diagnosed | |||||

| Mohammadi et al [27] | Not reported | 13 | Not reported | 140 | Not reported | Not reported | 0 | 0 | Not reported | 0 | |||||

| Tuberculosis Research Centre, Indian Council of Medical Research [28] | Not reported | 209 INHd resistant at intake | 779 at intake and 8358 over 15 years | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 22 over 15 years of f/ue and 260 per 100,000 person-years in INH-resistant HHf contacts | 18 | 22 | 4 INH resistant | |||||

| Denholm et al [29] | 47 | 47 | 570 | 49 LTBIg | Not reported | Not reported | 2 | Not reported | Not reported | 2 | |||||

| Seddon et al [23] | Not reported | Not reported | 281 | 228 | Not reported (102 LTBI) | Not reported | 15 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |||||

| Adler-Shohet et al [30] | 1 | 1 | Not reported | 118 | 31 TSTh posi (21 initially and 10 at repeat) | 31 on LTBI treatment had 2-year f/u | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Garcia-Prats et al [31] | 1 | 1 | 38 | 34 | None | Not reported | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Titiyos et al [32] | 508 | 508 | 155 family members in households of 29 symptomatic contacts | 155 | Unclear (29 symptomatic contacts were initially identified and evaluated) | Not reported | 16 | Not reported | Not reported | 16 confirmed MDR-TBj | |||||

| Arnold et al [33] | 1 | 1 | 35 | 33 | Not reported | Not reported | 2 at baseline (2 in 2-year f/u) | 0 | Not reported | 2 XDRk (1 confirmed and 1 probable) | |||||

| García et al [34] | 1 | 1 | 39 | 39 | 19 Mantoux pos of which 1 had CXRl changes | Not reported | 5 (within 2-year f/u) | Not reported | 4 | 4 INH resistant (same strain as index case) | |||||

| Javaid et al [35] | 200 | 154 | Not reported | 610 | 218 symptoms, 51 AFBm-positive, and Nrn with abnormal CXR not reported | Not reported | 51 | 10 | Not reported | 41 | |||||

| Fournier et al [36] | 68 | 32 | 84 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 2 | Not reported | 3 MDR-TB | |||||

| Golla et al [37] | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 229 | Not reported | 226 | 15 (7 bacteriological) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |||||

| Lee et al [38] | 1 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 2 asymptomatic with minimal nodules in baseline chest CTo scan | 2 followed up with chest CT scan | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Chatla et al [39] | 1602 | 1602 | 4858 | 4771 | 793 | 781 | 34 | 19 | 34 | 15 | |||||

| Dayal et al [40] | Not reported | 43 | Not reported | 100 | Not reported | 100 | 41 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |||||

| Hiruy et al [24] | 111 | 111 | 340 | 331 | 20 | 20 | 9 | 1 | 20 | 8 | |||||

| Huerga et al [41] | 265 | 111 | 198 | 150 at baseline and 138 at f/u | Not reported | Not reported | 3 at baseline (none with f/u) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |||||

| Boonthanapat et al [42] | 91 | 43 | 174 | 70 had screening records | 3 abnormal CXRs | Not reported | 1 identified, but no screening records for this one | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |||||

| Hoang et al [43] | 112 | 99 | 496 | 325 at baseline and 160 at f/u | 36 symptoms, 12 abnormal CXR, and 27 at f/u | 48 at baseline and 27 at f/u | 1 (no TB at f/u) | 1 | 48 | 0 | |||||

| Honjepari et al [44] | 67 | 67 total (only 25 DR-TB) | 697 | 635 total and 23 DR-TB contacts | 156 | 114 | 9 | 5 | Not reported | 4 (2 bacteriologically and 2 clinically) | |||||

| Kigozi et al [45] | Not reported | 92 | 297 (only 6 contacts of MDR-TB cases) | 259 (6) | 102 (1) | 48 (1) | 17 (0) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |||||

| Phyo et al [26] | 556 | 556 | 1908 | 1134 | 344 presumptive TB | 186 presumptive TB and 213 others (399 in total) | 27 (6 bacteriologically and 21 clinically) | 15 | 20 | 5 | |||||

| Gupta et al [46] | 308 | 284 | 1016 | 1007 | 228 signs and symptoms and 169/969 abnormal CXR | 1007 | 121 (17 bacteriological) | 11 | 16 | 5 | |||||

| Kyaw et al [25] | Not reported | 210 | Not reported | 620 | 240 symptoms and Nr with abnormal CXR not reported | 169 AFB/Xpert (71 symptomatic contacts did not receive AFB/Xpert) | 24 (7 bacteriologically and 17 clinically) | 22 | 43 | 2 | |||||

| Malik et al [47] | Not reported | 100 | 800 (8 on TB treatment) | 737 | 402 symptoms or <18 years or DMp or HIV or low BMIq | 326 | 3 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |||||

| Paryani et al [48] | 129 | 109 | 518 (22 with TB already on treatment and 2 diagnosed at baseline) | 495 (400 entered f/u) | Not reported | Not reported | 22 already on treatment (excluded), 2 diagnosed at baseline (excluded), and 14 at f/u | 6 | Not reported | 6 pre-XDR, 1 XDR, and 1 missing DSTr | |||||

| Shadrach et al [49] | Not reported | 87 | Not reported | Not reported | 285 | 271 | 97 | 35 | Not reported | 62 | |||||

| van de Water et al [50] | 284 | 284 | 959 | 336 | Not reported | Not reported | 30 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |||||

| Chang et al [51] | Not reported | 55 | 247 | 215 | 8 abnormal CXR | Not reported | 1 | 1 | Not reported | Not reported | |||||

| Kim et al [52] | 305 | 152 RR-TB | 1324 | 303 children <15 years | 69 symptoms | 93 smear microscopy, 55 CXR, and 93 culture or molecular test | 4 bacteriologically and 49 clinically | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | |||||

| Ahmed et al [53] | 329 | 324 | 1911 | 1734 symptom screen, 281 Xpert, and 123 CXR only | Not reported | All contacts were eligible for Xpert regardless of symptoms | 20 | 0 | 20 | 2 clinically, 7 MDR/RRs TB, and 11 pre-XDR TB | |||||

| Ahmed and Dadlani [54] | 470 | 100 MDR-TB and 370 DS-TB | 830 | 830 | 218 symptoms | 102 GeneXpert, 76 Smear microscopy, and 11 CXR | 106 | 98 | Not reported | 8 MDR-TB | |||||

| Apolisi et al [55] | Not reported | 48 | 146 | 112 | 19 symptoms | 55 CXR only, 19 CXR and sputum, and 1 sputum only | 11 (2 bacteriologically and 9 clinically) | 1 (bacteriologically) | Not reported | 10 (1 indeterminate for rifampicin susceptibility and 9 clinically) | |||||

| Rekart et al [56] | Not reported | 830 RR-TB | Not reported | 6654 | 269 symptoms | 1549 | 49 | 1 | 28 had DST | 47 RR (16 MDR, 12 XDR) and 1 INH resistant | |||||

aDR-TB: drug-resistant tuberculosis.

bTB: tuberculosis.

cDS-TB: drug-susceptible tuberculosis.

dINH: isoniazid.

ef/u: follow-up.

fHH: household.

gLTBI: latent TB infection.

hTST: tuberculin skin test.

ipos: positive.

jMDR-TB: multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

kXDR: extensively drug-resistant.

lCXR: chest radiography.

mAFB: acid fast bacilli.

nnr: number.

oCT: computed tomography.

pDM: diabetes mellitus.

qBMI: body mass index.

rDST: drug susceptibility testing.

sRR: rifampicin resistant.

Outbreak Investigations

The Dictionary of Epidemiology defines an outbreak as “an epidemic limited to localized increase in the incidence of disease, e.g., village, town, or closed institution” [57]. In the included studies, it was not always reported whether the number of identified patients was more than expected over a particular period. It was not always clear if a study was indeed an investigation of an outbreak. Studies are summarized in Table 5. These were mostly in lower TB burden countries. They were all descriptive and focused on different aspects of an outbreak, for example, contact investigation and follow-up, preventive measures, and transmission chains.

Table 5.

Overview of outbreak investigations.

| Study | Country | Disease | Population | Cases that triggered a response | Focus of the paper |

| Valway et al [58] | United States (New York) | MDR-TBa | Inmates from a prison in Upstate New York | 4 inmates from one prison were diagnosed in the summer of 1991 | Transmission patterns and contact investigation results |

| Ridzon et al [59] | United States (California) | DR-TBb | California high-school students | 4 students were diagnosed in spring 1993 | Findings from an outbreak investigation |

| Breathnach et al [60] | United Kingdom (London) | MDR-TB | Patients who were HIV positive at St Thomas’ Hospital in London | 8 patients were identified between 1995 and 1997 | Epidemiology and control of the hospital outbreak |

| Holdsworth et al [61] | United Kingdom (London) | MDR-TB | Nosocomial outbreak at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHSc Trust | 8 patients were identified in the summer of 1996 | Management of public relations following the outbreak |

| Moro et al [62] | Italy | MDR-TB | Patients infected by HIV and hospitalized in an HIV ward in Milan, Italy | 33 patients were diagnosed between October 1992 and February 1994 | Risk factors for transmission and the effectiveness of infection control measures |

| Schmid et al [63] | Austria | MDR-TB | Refugees in Austria | In 2005-2006 the Austrian laboratory for TBd identified 4 MDR-TB cases with similar genotypes | The chain of transmission |

| Asghar et al [64] | United States (Florida) | Mycobacterium tuberculosis resistant to isoniazid | HIV-positive, rock cocaine (crack) users who lived in low-income neighborhoods in Miami | 18 cases with matching spoligotypes were identified between January 2004 and May 2005 | Transmission patterns and recommendations for TB control in this population |

| Fred et al [65] | Federated States of Micronesia | MDR-TB | Cluster of patients with MDR-TB in Chuuk State | A cluster of 5 patients were identified in May 2008 | Contact tracing and control measures |

| Chee et al [66] | Singapore | MDR-TB | LANe gaming centers | In 2012, 5 men who attended 2 LAN gaming centers were diagnosed with MDR-TB | Highlights gaming centers as potential hotspots for TB transmission and notes challenges when conducting contact-tracing investigations |

| Norheim et al [67] | Norway | Streptomycin resistant TB | Students attending training sessions at an educational institution in Oslo, Norway | 3 students were identified within one week in April 2013 | Transmission patterns linking data from contact tracing to data from WGSf |

| Ho et al [68] | Singapore | MDR-TB | Residents of an 11-storey apartment block | 6 residents were identified between February 2012 and May 2016 | The cluster investigation and results from mass screening |

| Popovici et al [69] | Romania | XDR-TBg | Foreign medical students at a Romanian university | A cluster of 3 patients was identified in October 2015 | Results from contact investigation and the efforts to identify the source case |

| Zhang et al [70] | China | MDR-TB | School in Zhejiang Province | A student was diagnosed in May 2014 | Results from classmate contact investigation |

| Li et al [71] | China | MDR-TB | Senior high school | A female student diagnosed in March 2020 | Results from household, classmate, and faculty investigations |

| Kobayashi et al [72] | Japan | MDR-TB | Japanese language school in Tokyo | A student was diagnosed in September 2019 | Results from analysis of outbreak cases |

| Wu et al [73] | China | RR-TBh | Middle school in Jiangsu Province | Unclear. 12 patients were diagnosed with TB of whom 6 were RR-TB. | Describe characteristics and epidemiology of outbreak and suggestions for prevention and control of school TB |

| Groenweghe et al [74] | United States (Kansas) | MDR-TB | Households from the same apartment complex and their contacts | The first person identified was an infant hospitalized in November 2021. An investigation identified 4 additional household members with MDR-TB. | Public Health Response and results from contact investigations |

aMDR-TB: multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

bDR-TB: drug-resistant tuberculosis.

cNHS: National Health Services.

dTB: tuberculosis.

eLAN: local area network.

fWGS: whole-genome sequencing.

gXDR-TB: extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis.

hRR-TB: rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis.

Airline Contact Investigations

Three studies described airline DR-TB contact investigation. An der Heiden et al [75] investigated passengers and crew members after exposure to an individual with XDR-TB. The response rate was 83%. No secondary TB cases were reported and 1 individual with TB infection, probably newly acquired, was identified. Kornylo-Duong et al [76] evaluated passenger contacts of individuals with MDR-TB. More than 65% were lost to follow-up. No secondary TB cases were reported. Eight contacts tested positive for latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI); however, it was unknown if these contacts were recent converters as they might have acquired LTBI from their countries of residence. Glasauer et al [77] analyzed international contact tracing notifications received by Germany from other countries, with a focus on air travel. The high variability in the completeness of contact tracing information made analyses a challenge.

Epidemiological Analyses

Nitta et al [78], Anderson et al [79], de Vries et al [80], and Suppli et al [81] described transmission patterns of DR-TB in Los Angeles County (1993-1998), the United Kingdom (2004-2007), and the Netherlands (2010-2019 and 2018-2019), respectively. Intervention strategies to find those with TB disease are mentioned, but not described in detail. Villa et al [82] described a cluster of 16 pre-XDR and XDR-TB cases in Italy between 2016 and 2020 as well as the role of whole-genome sequencing in TB surveillance.

Public-Private Partnership Program

Joloba et al [83] described a program to improve MDR-TB detection by improving access to rapid and reliable DST, redesigning the TB specimen transport network, and training health care workers in Uganda. This study enhanced the care-seeking pathway (Figure 1, green dashed pathway) to specifically improve MDR-TB diagnosis and no screening took place.

E-registry Program

Naker et al [84] described a qualitative study in Mongolia to assess the feasibility and acceptability of an e-registry tool to simplify the systematic screening of MDR-TB contacts. Of 42 index cases invited to take part in the pilot study, 10 declined participation due to concerns about data security.

Discussion

Key Findings

This scoping review charts the existing literature on DR-TB case finding. More than 60% of identified studies described DR-TB contact investigations. Included studies were all descriptive and no trials were identified. There is a lack of primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews assessing the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of different DR-TB case-finding strategies. Case-finding strategies were not always reported in enough detail to deduce the specific pathways in our systems-based logic model (Figure 1), for example, whether symptomatic contacts were invited to a TB diagnostic service or whether contacts were screened at home or invited for screening at a health facility; however, except for target group differences, for example, contacts of DR-TB source cases compared with DS-TB source cases, and DST when presumptive DR-TB is identified, we did not note any differences between DR-TB case-finding and DS-TB case-finding strategies. Information on factors that may influence the yield of TB disease, like the number of contacts identified, screened, and evaluated, when these contacts were evaluated (baseline or follow-up), and which screening and diagnostic tools used [85] were seldom reported in detail.

Previous Work

Although conclusions about the most effective DR-TB case-finding strategy cannot be drawn, several reviews looked at the possible effects of active TB case finding (screening pathways in Figure 1) compared with passive TB case finding (care-seeking pathways in Figure 1) in general. Two Cochrane reviews failed to identify any studies for inclusion. Fox et al [86] aimed to compare the diagnostic yield of TB disease between active case finding and passive case finding in TB contacts but did not identify any trials for inclusion in the review. Braganza Menezes et al [87] also could not identify trials for inclusion in a review aiming to assess the effectiveness of novel methods, for example, social network analysis, of contact tracing versus the current standard of care to identify individuals with TB infection or TB disease. A review by Kranzer et al [88] included observational studies and concluded that screening compared with standard care increases the number of patients with TB disease found in the short term, but that it is unknown whether it impacts TB epidemiology. This finding was underpinned by another Cochrane review. Mhimbira et al [5] found that active case-finding strategies may result in increased case finding in the short term, but long-term outcomes were lacking. Except for the unknown effect of TB screening on TB epidemiology, the effect of screening on individual outcomes had been studied by Telisinghe et al [89] and Kranzer et al [88]. These reviews found limited patient outcome data and no difference in treatment outcomes between active and passive case findings. While it is known that screening may increase the number of identified cases, it is unclear if TB screening makes a difference to TB epidemiology and individual outcomes compared with passive case finding.

Implications for Research

There is a need for standardization of terminology, design, and reporting of DR-TB case-finding studies, especially contact investigation studies. Future research should focus on clear definitions, methodology, and detailed descriptions of all intervention components. There is also a need for well-conducted randomized controlled trials assessing the effect of active case finding on individual outcomes and long-term TB epidemiological outcomes.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of our review included a thorough search strategy and the use of a systems-based logic model. Nevertheless, there were some limitations. We searched several databases with no date or language restriction, but we did not translate all full-text articles. Studies that were not translated (n=4) are reported in the list of excluded studies (Multimedia Appendix 4) and from the translated abstracts it seems that similar study designs were found to those of included contact investigation studies. Our review excluded patients with TB symptoms seeking care, patients diagnosed with TB, and laboratory samples or laboratory isolates because the focus of this review was on active case finding. It should therefore be noted that studies that investigated strategies to improve identification of DR-TB after clinical identification of presumptive DR-TB cases, or studies that screened laboratory samples were not part of this review. Furthermore, for collating, summarizing, and reporting the results, we initially envisaged using our systems-based logic model as a framework to describe different case-finding strategies and resulting pathways. However, reporting was incomplete and inconsistent, and we were not able to describe pathways in detail. Nevertheless, the logic model guided our interpretation of whether a case-finding study involved screening or not. Finally, for contact investigation studies, we included studies that reported on the number of individuals with TB disease diagnosed, even if the study focused on LTBI testing and treatment. This might be a reason why the screening and diagnostic pathways were not always reported in detail. However, it is important to note that in contact investigation studies, the active case-finding component and the LTBI treatment component are both important aspects of early case finding and prevention.

Conclusions

Existing descriptive reviews can be updated, but there is a dearth of knowledge on the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of DR-TB case-finding strategies to inform policy and practice. There is also a need for standardization of terminology, design, and reporting of DR-TB case-finding studies, especially contact investigation studies, to decrease a large amount of research waste and increase the number of studies that could be synthesized and meta-analyzed in high-impact systematic reviews in the future [90].

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Anel Schoonees and Vittoria Lutje, our information specialists, for their assistance with the search strategy. SSvW is supported by the Research, Evidence and Development Initiative (READ-It). READ-It (project number 300342-104) is funded by UK aid from the UK government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. MC is supported jointly by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) under the MRC/FCDO Concordat agreement and is also part of the EDCTP2 program supported by the European Union. JAS is supported by a Clinician Scientist Fellowship jointly funded by the UK MRC and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement (MR/R007942/1). GH received financial assistance from the European Union (grant DCI-PANAF/2020/420-028), through the African Research Initiative for Scientific Excellence (ARISE), pilot program. ARISE is implemented by the African Academy of Sciences with support from the European Commission and the African Union Commission.

Abbreviations

- DR-TB

drug-resistant tuberculosis

- DS-TB

drug-susceptible tuberculosis

- DST

drug-susceptibility testing

- LTBI

latent tuberculosis infection

- MDR-TB

multidrug-resistant tuberculosis

- PRISMA-ScR

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews

- TB

tuberculosis

- XDR-TB

extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis

PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) checklist.

Detailed search strategy.

Characteristics of drug-resistant TB contact investigation studies.

List of excluded studies with reasons.

Data Availability

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Multimedia Appendices.

Footnotes

Authors' Contributions: MC and SSvW conceived the study idea. SSvW, MN, LV, FWL, CCL, and MC performed title, abstract, and full-text screening. All authors assisted with data extraction and analyses. SSvW drafted the paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Allué-Guardia A, García JI, Torrelles JB. Evolution of drug-resistant strains and their adaptation to the human lung environment. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:612675. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.612675. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.612675/full . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Global tuberculosis report 2021. World Health Organization. 2021. [2024-05-10]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240037021 .

- 3.WHO Drug-resistant tuberculosis remains a public health crisis. World Health Organization. 2022. [2022-10-19]. https://www.who.int/multi-media/details/drug-resistant-tuberculosis-remains-a-public-health-crisis-2022 .

- 4.WHO Systematic screening for active tuberculosis: an operational guide. World Health Organization. 2015. [2024-05-10]. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/181164/9789241549172_eng.pdf?sequence=1 .

- 5.Mhimbira FA, Cuevas LE, Dacombe R, Mkopi A, Sinclair D. Interventions to increase tuberculosis case detection at primary healthcare or community-level services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11(11):CD011432. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011432.pub2. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011432.pub2/full . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heuvelings CC, de Vries SG, Greve PF, Visser BJ, Bélard S, Janssen S, Cremers AL, Spijker R, Shaw B, Hill RA, Zumla A, Sandgren A, van der Werf MJ, Grobusch MP. Effectiveness of interventions for diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in hard-to-reach populations in countries of low and medium tuberculosis incidence: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(5):e144–e158. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30532-1. https://core.ac.uk/reader/80782237?utm_source=linkout .S1473-3099(16)30532-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x .10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–146. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050. https://journals.lww.com/ijebh/fulltext/2015/09000/guidance_for_conducting_systematic_scoping_reviews.5.aspx . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 .1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö, Straus SE. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M18-0850 .2700389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Wyk SS, Nliwasa M, Seddon JA, Hoddinott G, Viljoen L, Nepolo E, Günther G, Ruswa N, Lin HH, Niemann S, Gandhi NR, Shah NS, Claassens M. Case-finding strategies for drug-resistant tuberculosis: protocol for a scoping review. JMIR Res Protoc. 2022;11(12):e40009. doi: 10.2196/40009. https://www.researchprotocols.org/2022/12/e40009 .v11i12e40009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 .10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO Systematic screening for active tuberculosis: principals and recommendations. World Health Organization. 2013. [2024-05-10]. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/84971 . [PubMed]

- 15.WHO Consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 2: screening- systematic screening for tuberculosis disease. World Health Organization. 2021. [2024-05-10]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022676 . [PubMed]

- 16.van Wyk SS, Medley N, Young T, Oliver S. Repairing boundaries along pathways to tuberculosis case detection: a qualitative synthesis of intervention designs. Health Res Policy Syst. 2022;20(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00811-0. https://health-policy-systems.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12961-021-00811-0 .10.1186/s12961-021-00811-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abubakar I. Tuberculosis and air travel: a systematic review and analysis of policy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(3):176–183. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70028-1.S1473-3099(10)70028-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox GJ, Barry SE, Britton WJ, Marks GB. Contact investigation for tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2013;41(1):140–156. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00070812. https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/41/1/140 .09031936.00070812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah NS, Yuen CM, Heo M, Tolman AW, Becerra MC. Yield of contact investigations in households of patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):381–391. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit643. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/58/3/381/336016?login=false .cit643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kodama C, Lange B, Olaru ID, Khan P, Lipman M, Seddon JA, Sloan D, Grandjean L, Ferrand RA, Kranzer K. Mycobacterium transmission from patients with drug-resistant compared to drug-susceptible TB: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(4):1701044. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01044-2017. https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/50/4/1701044 .50/4/1701044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Svadzian A, Sulis G, Gore G, Pai M, Denkinger CM. Differential yield of universal versus selective drug susceptibility testing of patients with tuberculosis in high-burden countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(10):e003438. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003438. https://gh.bmj.com/content/5/10/e003438 .bmjgh-2020-003438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiang SS, Brooks MB, Jenkins HE, Rubenstein D, Seddon JA, van de Water BJ, Lindeborg MM, Becerra MC, Yuen CM. Concordance of drug-resistance profiles between persons with drug-resistant tuberculosis and their household contacts: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(2):250–263. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa613. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/73/2/250/5843623?login=false .5843623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seddon JA, Hesseling AC, Godfrey-Faussett P, Fielding K, Schaaf HS. Risk factors for infection and disease in child contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:392. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-392. https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2334-13-392 .1471-2334-13-392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hiruy N, Melese M, Habte D, Jerene D, Gashu Z, Alem G, Jemal I, Tessema B, Belayneh B, Suarez PG. Comparison of the yield of tuberculosis among contacts of multidrug-resistant and drug-sensitive tuberculosis patients in Ethiopia using GeneXpert as a primary diagnostic test. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;71:4–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.03.011. https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(18)30070-5/fulltext .S1201-9712(18)30070-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kyaw NTT, Sithu A, Satyanarayana S, Kumar AMV, Thein S, Thi AM, Wai PP, Lin YN, Kyaw KWY, Tun MMT, Oo MM, Aung ST, Harries AD. Outcomes of community-based systematic screening of household contacts of patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Myanmar. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019;5(1):2. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed5010002. https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/5/1/2 .tropicalmed5010002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phyo AM, Kumar AMV, Soe KT, Kyaw KWY, Thu AS, Wai PP, Aye S, Saw S, Maung HMW, Aung ST. Contact investigation of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients: a mixed-methods study from Myanmar. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2019;5(1):3. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed5010003. https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/5/1/3 .tropicalmed5010003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohammadi A, Nassor ZS, Behlim T, Mohammadi E, Govindarajan R, Al Maniri A, Smego RA. Epidemiological and cost analysis of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Oman. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14(6):1240–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuberculosis Research Centre‚ Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) Risk of tuberculosis among contacts of isoniazid-resistant and isoniazid-susceptible cases. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011 Jun;15(6):782–788. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.09.0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Denholm JT, Leslie DE, Jenkin GA, Darby J, Johnson PDR, Graham SM, Brown GV, Sievers A, Globan M, Brown LK, McBryde ES. Long-term follow-up of contacts exposed to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Victoria, Australia, 1995-2010. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(10):1320–1325. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0092.ijtld120092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adler-Shohet FC, Low J, Carson M, Girma H, Singh J. Management of latent tuberculosis infection in child contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(6):664–666. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000260. https://journals.lww.com/pidj/fulltext/2014/06000/management_of_latent_tuberculosis_infection_in.29.aspx . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garcia-Prats AJ, Zimri K, Mramba Z, Schaaf HS, Hesseling AC. Children exposed to multidrug-resistant tuberculosis at a home-based day care centre: a contact investigation. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(11):1292–1298. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Titiyos A, Jerene D, Enquselasie F. The yield of screening symptomatic contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis cases at a tertiary hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:501. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1442-z. https://bmcresnotes.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13104-015-1442-z .10.1186/s13104-015-1442-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnold A, Witney AA, Vergnano S, Roche A, Cosgrove CA, Houston A, Gould KA, Hinds J, Riley P, Macallan D, Butcher PD, Harrison TS. XDR-TB transmission in London: case management and contact tracing investigation assisted by early whole genome sequencing. J Infect. 2016;73(3):210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.04.037. https://www.journalofinfection.com/article/S0163-4453(16)30125-6/fulltext .S0163-4453(16)30125-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.García CH, Cea LM, Espinilla VF, Del Prado GRL, Arribas SF, García IA, Rubio V, Vesenbeckh S, Bouza JME. Outbreak of isoniazid-resistant tuberculosis in an immigrant community in Spain. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52(6):289–292. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2015.07.014.S0300-2896(15)00322-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Javaid A, Khan MA, Khan MA, Mehreen S, Basit A, Khan RA, Ihtesham M, Ullah I, Khan A, Ullah U. Screening outcomes of household contacts of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis patients in Peshawar, Pakistan. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2016;9(9):909–912. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.07.017. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1995764516301547?via%3Dihub .S1995-7645(16)30154-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fournier A, Bernard C, Sougakoff W, Quelet S, Antoun F, Charlois-Ou C, Dormant I, Dufour MO, Hocine N, Jarlier V, Veziris N. Neither genotyping nor contact tracing allow correct understanding of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis transmission. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(3):1700891. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00891-2017. https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/50/3/1700891 .50/3/1700891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Golla V, Snow K, Mandalakas AM, Schaaf HS, Du Preez K, Hesseling AC, Seddon JA. The impact of drug resistance on the risk of tuberculosis infection and disease in child household contacts: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):593. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2668-2. https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-017-2668-2 .10.1186/s12879-017-2668-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee SC, Yoon SH, Goo JM, Yim JJ, Kim CK. Submillisievert computed tomography of the chest in contact investigation for drug-resistant tuberculosis. J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32(11):1779–1783. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2017.32.11.1779. https://jkms.org/DOIx.php?id=10.3346/jkms.2017.32.11.1779 .32.1779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chatla C, Jaju J, Achanta S, Samyuktha R, Chakramahanti S, Purad C, Chepuri R, Nair SA, Parmar M. Active case finding of rifampicin sensitive and resistant TB among household contacts of drug resistant TB patients in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana states of India—a systematic screening intervention. Indian J Tuberc. 2018;65(3):218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2018.02.004.S0019-5707(17)30158-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dayal R, Agarwal D, Bhatia R, Bipin C, Yadav NK, Kumar S, Narayan S, Goyal A. Tuberculosis burden among household pediatric contacts of adult tuberculosis patients. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85(10):867–871. doi: 10.1007/s12098-018-2661-9.10.1007/s12098-018-2661-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huerga H, Sanchez-Padilla E, Melikyan N, Atshemyan H, Hayrapetyan A, Ulumyan A, Bastard M, Khachatryan N, Hewison C, Varaine F, Bonnet M. High prevalence of infection and low incidence of disease in child contacts of patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis: a prospective cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(7):622–628. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-315411. https://adc.bmj.com/content/104/7/622 .archdischild-2018-315411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boonthanapat N, Soontornmon K, Pungrassami P, Sukhasitwanichkul J, Mahasirimongkol S, Jiraphongsa C, Monkongdee P, Angchokchatchawal K, Wiratsudakul A. Use of network analysis multidrug-resistant tuberculosis contact investigation in Kanchanaburi, Thailand. Trop Med Int Health. 2019;24(3):320–327. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13190. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/tmi.13190 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoang TTT, Nguyen VN, Dinh NS, Thwaites G, Nguyen TA, van Doorn HR, Cobelens F, Wertheim HFL. Active contact tracing beyond the household in multidrug resistant tuberculosis in Vietnam: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):241. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6573-z. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-019-6573-z .10.1186/s12889-019-6573-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Honjepari A, Madiowi S, Madjus S, Burkot C, Islam S, Chan G, Majumdar SS, Graham SM. Implementation of screening and management of household contacts of tuberculosis cases in Daru, Papua New Guinea. Public Health Action. 2019;9(Suppl 1):S25–S31. doi: 10.5588/pha.18.0072. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31579646 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kigozi NG, Heunis JC, Engelbrecht MC. Yield of systematic household contact investigation for tuberculosis in a high-burden metropolitan district of South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):867. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7194-2. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-019-7194-2 .10.1186/s12889-019-7194-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gupta A, Swindells S, Kim S, Hughes MD, Naini L, Wu X, Dawson R, Mave V, Sanchez J, Mendoza A, Gonzales P, Kumarasamy N, Comins K, Conradie F, Shenje J, Fontain SN, Garcia-Prats A, Asmelash A, Nedsuwan S, Mohapi L, Lalloo UG, Ferreira ACG, Mugah C, Harrington M, Jones L, Cox SR, Smith B, Shah NS, Hesseling AC, Churchyard G. Feasibility of identifying household contacts of rifampin-and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis cases at high risk of progression to tuberculosis disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(3):425–435. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz235. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/70/3/425/5426963?login=false .5426963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malik AA, Fuad J, Siddiqui S, Amanullah F, Jaswal M, Barry Z, Jabeen F, Fatima R, Yuen CM, Salahuddin N, Khan AJ, Keshavjee S, Becerra MC, Hussain H. Tuberculosis preventive therapy for individuals exposed to drug-resistant tuberculosis: feasibility and safety of a community-based delivery of fluoroquinolone-containing preventive regimen. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(9):1958–1965. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz502. https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/70/9/1958/5514486?login=false .5514486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paryani RH, Gupta V, Singh P, Verma M, Sheikh S, Yadav R, Mansoor H, Kalon S, Selvaraju S, Das M, Laxmeshwar C, Ferlazzo G, Isaakidis P. Yield of systematic longitudinal screening of household contacts of Pre-Extensively Drug Resistant (PreXDR) and Extensively Drug Resistant (XDR) tuberculosis patients in Mumbai, India. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2020;5(2):83. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed5020083. https://www.mdpi.com/2414-6366/5/2/83 .tropicalmed5020083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shadrach BJ, Kumar S, Deokar K, Singh GV, Hariharan. Goel R. A study of multidrug resistant tuberculosis among symptomatic household contacts of MDR-TB patients. Indian J Tuberc. 2021;68(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2020.09.030.S0019-5707(20)30178-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van de Water BJ, Vance AJ, Ramangoaela L, Botha M, Becerra MC. Prevention care cascade in people exposed to drug-resistant TB. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2020;24(12):1305–1306. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.20.0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang V, Ling RH, Velen K, Fox GJ. Latent tuberculosis infection among contacts of patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in New South Wales, Australia. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(3):00149–2021. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00149-2021. https://openres.ersjournals.com/content/7/3/00149-2021 .00149-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim S, Wu X, Hughes MD, Upton C, Narunsky K, Mendoza-Ticona A, Khajenoori S, Gonzales P, Badal-Faesen S, Shenje J, Omoz-Oarhe A, Rouzier V, Garcia-Prats AJ, Demers AM, Naini L, Smith E, Churchyard G, Swindells S, Shah NS, Gupta A, Hesseling AC. High prevalence of tuberculosis infection and disease in child household contacts of adults with rifampin-resistant tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2022;41(5):e194–e202. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003505. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/35239624 .00006454-202205000-00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahmed S, Lotia-Farrukh I, Khan PY, Adnan S, Sodho JS, Bano S, Siddiqui MR, Ghafoor A, Isani AK, Salahuddin N, Khan U. High prevalence of multidrug-resistant TB among household contacts in a high burden setting. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2023;27(8):646–648. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.23.0123. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/37491755 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ahmed N, Dadlani S. Intervention to increase tuberculosis case detection through community engagement and contact screening in Sindh Pakistan. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2023;30(18):2284–2292. https://jptcp.com/index.php/jptcp/article/view/3437/3365 . [Google Scholar]

- 55.Apolisi I, Cox H, Tyeku N, Daniels J, Mathee S, Cariem R, Douglas-Jones B, Ngambu N, Mudaly V, Mohr-Holland E, Isaakidis P, Pfaff C, Furin J, Reuter A. Tuberculosis diagnosis and preventive monotherapy among children and adolescents exposed to rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis in the household. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2023;10(3):ofad087. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofad087. https://academic.oup.com/ofid/article/10/3/ofad087/7049594?login=false .ofad087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rekart ML, Aung A, Cullip T, Mulanda W, Mun L, Pirmahmadzoda B, Kliescokova J, Achar J, Alvarez JL, Sitali N, Sinha A. Household drug-resistant TB contact tracing in Tajikistan. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2023;27(10):748–753. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.23.0066. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/37749832 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Last JM. In: A Dictionary of Epidemiology, 4th Edition. Spasoff RA, Harris SS, Thuriaux MC, editors. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. p. 129. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valway SE, Richards SB, Kovacovich J, Greifinger RB, Crawford JT, Dooley SW. Outbreak of multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis in a New York state prison, 1991. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140(2):113–122. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ridzon R, Kent JH, Valway S, Weismuller P, Maxwell R, Elcock M, Meador J, Royce S, Shefer A, Smith P, Woodley C, Onorato I. Outbreak of drug-resistant tuberculosis with second-generation transmission in a high school in California. J Pediatr. 1997;131(6):863–868. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70034-9.S0022-3476(97)70034-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breathnach AS, de Ruiter A, Holdsworth GM, Bateman NT, O'Sullivan DG, Rees PJ, Snashall D, Milburn HJ, Peters BS, Watson J, Drobniewski FA, French GL. An outbreak of multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis in a London teaching hospital. J Hosp Infect. 1998;39(2):111–117. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(98)90324-3.S0195-6701(98)90324-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holdsworth GM, Breathnach A, Asboe D, Free D, Cranston R, Peters BS, de Ruiter A. Controlled management of public relations following a public health incident. J Public Health Med. 1999;21(3):251–254. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/21.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moro ML, Errante I, Infuso A, Sodano L, Gori A, Orcese CA, Salamina G, D'Amico C, Besozzi G, Caggese L. Effectiveness of infection control measures in controlling a nosocomial outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among HIV patients in Italy. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4(1):61–68. https://air.unimi.it/handle/2434/629094 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmid D, Fretz R, Kuo HW, Rumetshofer R, Meusburger S, Magnet E, Hürbe G, Indra A, Ruppitsch W, Pietzka AT, Allerberger F. An outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among refugees in Austria, 2005-2006. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12(10):1190–1195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Asghar RJ, Patlan DE, Miner MC, Rhodes HD, Solages A, Katz DJ, Beall DS, Ijaz K, Oeltmann JE. Limited utility of name-based tuberculosis contact investigations among persons using illicit drugs: results of an outbreak investigation. J Urban Health. 2009;86(5):776–780. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9378-z. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/19533366 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fred D, Desai M, Song R, Bamrah S, Pavlin BI, Heetderks A, Ekiek MJ. Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis in Chuuk State Federated States of Micronesia, 2008-2009. Pac Health Dialog. 2010;16(1):123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chee CBE, Gan SH, Ong RT, Sng LH, Wong CW, Cutter J, Gong M, Seah HM, Hsu LY, Solhan S, Ooi PL, Xia E, Lim JT, Koh CK, Lim SK, Lim HK, Wang YT. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis outbreak in gaming centers, Singapore, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(1):179–180. doi: 10.3201/eid2101.141159. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/21/1/14-1159_article . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Norheim G, Seterelv S, Arnesen TM, Mengshoel AT, Tønjum T, Rønning JO, Eldholm V. Tuberculosis outbreak in an educational institution in Norway. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(5):1327–1333. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01152-16. https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/jcm.01152-16 .JCM.01152-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ho ZJM, Chee CBE, Ong RTH, Sng LH, Peh WLJ, Cook AR, Hsu LY, Wang YT, Koh HF, Lee VJM. Investigation of a cluster of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis in a high-rise apartment block in Singapore. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;67:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.12.010. https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(17)30322-3/fulltext .S1201-9712(17)30322-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Popovici O, Monk P, Chemtob D, Chiotan D, Freidlin PJ, Groenheit R, Haanperä M, Homorodean D, Mansjö M, Robinson E, Rorman E, Smith G, Soini H, Van Der Werf MJ. Cross-border outbreak of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis linked to a university in Romania. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146(7):824–831. doi: 10.1017/S095026881800047X. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/epidemiology-and-infection/article/crossborder-outbreak-of-extensively-drugresistant-tuberculosis-linked-to-a-university-in-romania/CD484A8BD0CF79AD92B0EEF2B9A4352E .S095026881800047X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Y, Zhou L, Liu ZW, Chai CL, Wang XM, Jiang JM, Chen SH. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis transmission among middle school students in Zhejiang Province, China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):57. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00670-x. https://idpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40249-020-00670-x .10.1186/s40249-020-00670-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li D, Peng X, Hou S, Li T, Yu XJ. A tuberculosis outbreak during the COVID-19 pandemic—Hubei Province, China, 2020. China CDC Wkly. 2021;3(26):562–565. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2021.145. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/34594936 .ccdcw-3-26-562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kobayashi Y, Tateishi A, Hiroi Y, Minakuchi T, Mukouyama H, Ota M, Nagata Y, Hirao S, Yoshiyama T, Keicho N. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis outbreak among immigrants in Tokyo, Japan, 2019-2021. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2022;75(5):527–529. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2021.643. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2021.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu JZ, Fu J, Wang JM, Liu Q, Lu F. Epidemiological investigation of a rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis outbreak in a middle school in jiangsu province. Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2022;26(11):1259–1263. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Groenweghe E, Swensson L, Winans KD, Griffin P, Haddad MB, Brostrom RJ, Tuckey D, Lam CK, Armitige LY, Seaworth BJ, Corriveau EA. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis—Kansas, 2021-2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72(35):957–960. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7235a4. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/72/wr/mm7235a4.htm?s_cid=mm7235a4_w . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.An der Heiden Maria, Hauer B, Fiebig L, Glaser-Paschke G, Stemmler M, Simon C, Rüsch-Gerdes Sabine, Gilsdorf A, Haas W. Contact investigation after a fatal case of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB) in an aircraft, Germany, July 2013. Euro Surveill. 2017 Mar 23;22(12):30493. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.12.30493. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/28367796 .30493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kornylo-Duong K, Kim C, Cramer EH, Buff AM, Rodriguez-Howell D, Doyle J, Higashi J, Fruthaler CS, Robertson CL, Marienau KJ. Three air travel-related contact investigations associated with infectious tuberculosis, 2007-2008. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2010;8(2):120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.08.001.S1477-8939(09)00126-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Glasauer S, Kröger S, Haas W, Perumal N. International tuberculosis contact-tracing notifications in Germany: analysis of national data from 2010 to 2018 and implications for efficiency. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):267. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-04982-z. https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-020-04982-z .10.1186/s12879-020-04982-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nitta AT, Knowles LS, Kim J, Lehnkering EL, Borenstein LA, Davidson PT, Harvey SM, De Koning ML. Limited transmission of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis despite a high proportion of infectious cases in Los Angeles County, California. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(6):812–817. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.6.2103109. https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/ajrccm.165.6.2103109 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anderson LF, Tamne S, Brown T, Watson JP, Mullarkey C, Zenner D, Abubakar I. Transmission of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in the UK: a cross-sectional molecular and epidemiological study of clustering and contact tracing. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(5):406–415. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70022-2. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(14)70022-2/fulltext .S1473-3099(14)70022-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.de Vries G, Akkerman O, Boeree M, van Hest R, Kamst M, de Lange W, Magis-Escurra C, Meijer W, van Soolingen D. Diagnosis, treatment and transmission of rifampicin-resistant TB in the Netherlands, 2010-2019. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2023;27(6):471–477. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.22.0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Suppli CH, Norman A, Folkvardsen DB, Gissel TN, Weinreich UM, Koch A, Wejse C, Lillebaek T. First outbreak of Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB) in Denmark involving six Danish-born cases. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;117:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.02.017. https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(22)00095-9/fulltext .S1201-9712(22)00095-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Villa S, Tagliani E, Borroni E, Castellotti PF, Ferrarese M, Ghodousi A, Lamberti A, Senatore S, Faccini M, Cirillo DM, Codecasa LR. Outbreak of pre- and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in northern Italy: urgency of cross-border, multidimensional, surveillance systems. Eur Respir J. 2021;58(3):2100839. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00839-2021. https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/58/3/2100839 .13993003.00839-2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Joloba M, Mwangi C, Alexander H, Nadunga D, Bwanga F, Modi N, Downing R, Nabasirye A, Adatu FE, Shrivastava R, Gadde R, Nkengasong JN. Strengthening the tuberculosis specimen referral network in Uganda: the role of public-private partnerships. J Infect Dis. 2016;213 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S41–S46. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw035. https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/213/suppl_2/S41/2490738?login=false .jiw035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Naker K, Gaskell KM, Dorjravdan M, Dambaa N, Roberts CH, Moore DAJ. An e-registry for household contacts exposed to multidrug resistant TB in Mongolia. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):188. doi: 10.1186/s12911-020-01204-z. https://bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12911-020-01204-z .10.1186/s12911-020-01204-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Deya RW, Masese LN, Jaoko W, Muhwa JC, Mbugua L, Horne DJ, Graham SM. Yield and coverage of active case finding interventions for tuberculosis control:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tuberc Res Treat. 2022;2022:9947068. doi: 10.1155/2022/9947068. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/trt/2022/9947068/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fox GJ, Dobler CC, Marks GB. Active case finding in contacts of people with tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011(9):CD008477. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008477.pub2. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008477.pub2/full . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Braganza Menezes D, Menezes B, Dedicoat M. Contact tracing strategies in household and congregate environments to identify cases of tuberculosis in low- and moderate-incidence populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Aug 28;8(8):CD013077. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013077.pub2. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/31461540 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kranzer K, Afnan-Holmes H, Tomlin K, Golub JE, Shapiro AE, Schaap A, Corbett EL, Lönnroth K, Glynn JR. The benefits to communities and individuals of screening for active tuberculosis disease: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(4):432–446. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Telisinghe L, Ruperez M, Amofa-Sekyi M, Mwenge L, Mainga T, Kumar R, Hassan M, Chaisson LH, Naufal F, Shapiro AE, Golub JE, Miller C, Corbett EL, Burke RM, MacPherson P, Hayes RJ, Bond V, Daneshvar C, Klinkenberg E, Ayles HM. Does tuberculosis screening improve individual outcomes? A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;40:101127. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101127. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(21)00407-7/fulltext .S2589-5370(21)00407-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chan AW, Song F, Vickers A, Jefferson T, Dickersin K, Gøtzsche PC, Krumholz HM, Ghersi D, van der Worp HB. Increasing value and reducing waste: addressing inaccessible research. Lancet. 2014;383(9913):257–266. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62296-5. https://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24411650 .S0140-6736(13)62296-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) checklist.

Detailed search strategy.

Characteristics of drug-resistant TB contact investigation studies.

List of excluded studies with reasons.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Multimedia Appendices.