Abstract

Introduction

It is known that cognitive deficits are a core feature of schizophrenia and that in the general population, prior beliefs significantly influence learning and reasoning processes. However, the interaction of prior beliefs with cognitive deficits and their impact on performance in schizophrenia patients is still poorly understood. This study investigates the role of beliefs and cognitive variables (CVs) like working memory, associative learning, and processing speed on learning processes in individuals with schizophrenia. We hypothesize that beliefs will influence the ability to learn correct predictions and that first-episode schizophrenia patients (FEP) will show impaired learning due to cognitive deficits.

Methods

We used a predictive-learning task to examine how FEP (n = 23) and matched controls (n = 23) adjusted their decisional criteria concerning physical properties during the learning process when predicting the sinking behavior of two transparent containers filled with aluminum discs when placed in water.

Results

On accuracy, initial differences by group, trial type, and interaction effects of these variables disappeared when CVs were controlled. The differences by conditions, associated with differential beliefs about why the objects sink slower or faster, were seen in patients and controls, despite controlling the CVs' effect.

Conclusions

Differences between groups were mainly explained by CVs, proving that they play an important role than what is assumed in this type of task. However, beliefs about physical events were not affected by CVs, and beliefs affect in the same way the decisional criteria of the control or FEP patients' groups.

Keywords: Cognitive deficits, Beliefs, Predictive learning, First-episode schizophrenia

1. Introduction

Beliefs are crucial to predict the future and guide our decisions (Castillo et al., 2015; Valton et al., 2019). Schizophrenia patients present deficits in updating beliefs based on new evidence and changing behaviors in response to negative feedback (Adams et al., 2018; Evans et al., 2015; Frith and Friston, 2013; Serrano-Guerrero et al., 2020). These impairments could lead to inaccurate inferences (Griffin and Fletcher, 2017), biased internal models about the environment (Valton et al., 2019), and have been linked to positive symptoms (Horga et al., 2014; Schmack et al., 2013, Schmack et al., 2015; Kaplan et al., 2016; Teufel et al., 2015). However, some scholars propose that the evidence on how schizophrenia patients update their beliefs is inconclusive (Firestone and Scholl, 2016; Teufel and Nanay, 2017; Sterzer et al., 2018).

Predictions based on physical object properties are affected by beliefs, as shown in studies using the sinking objects paradigm (Kloos, 2007), which reveal that beliefs differentially affect predictions, even when object sinking conditions are the same (Castillo et al., 2017). This performance pattern is driven by prior knowledge and beliefs, but cognitive factors like working memory, processing speed, and associative learning also play a role (Brunyé and Taylor, 2008; Copeland and Radvansky, 2004; Kail et al., 2016; Klauer et al., 2000; Tamez et al., 2008).

Concerning cognitive functioning, some studies have found a worse patient's performance in syllogistic reasoning causal and probabilistic learning. In comparison, others have not seen differences and even better patient performance, suggesting that general intelligence and cognitive functions could be potential mechanisms that explain such contradictory findings (Cardella and Gangemi, 2015). Studies with psychiatric patients have found that processing speed could predict fluid reasoning, but only when working memory was considered (Kim and Park, 2018). Similarly, Randers et al. (2020) found that individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis often show impaired processing speed, which likely contributes to their overall cognitive difficulties. To explore these cognitive aspects further, we focused on a predictive task encompassing learning, reasoning, and belief-tracking activities. These activities are closely related to cognitive functions like working memory, associative learning, and processing speed, which are strongly connected to reasoning abilities. Given the cognitive impairments found in schizophrenia (Zanelli et al., 2019) and its impact on learning and reasoning (Cardella and Gangemi, 2015; Stuke et al., 2018), we tested the effects of CVs on performance by using the sinking-object paradigm in FEP and matched controls.

2. Method

2.1. Selection and description of participants

We included 23 FEP and 23 matched controls (Table 1). We excluded control participants exhibiting neurological, psychiatric disorders, or first-degree relatives suffering from schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Participants were recruited at three Chilean hospitals between 2016 and 2017. All participants provided written informed consent, following the protocol approved by the Universidad de Talca Ethics Committee (IRB, 2016–2019, #1161503).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patient and control groups — Mean (Standard Deviation).

| Patients |

Controls |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 23 | 23 | p |

| Gender (m = male; f = female) | 13 m, 10 f | 13 m, 10 f | |

| Age (years) | 19.83 (6.69) | 19.57 (6.43) | 0.89 |

| Educational level N | |||

| ≤12 years | 19 | 18 | >0.05 |

| >13 years | 4 | 5 | |

| Average educational level | 10.61 (2.59) | 11.09 (2.65) | 0.57 |

| Duration of illnessa | 9.55 (8.99) | ||

| PANSS positive | 15.48 (5.72) | ||

| PANSS negative | 19.04 (7.86) | ||

| PANSS general | 37.22 (14.40) | ||

| Processing speed (WAIS, Symbol search) | 24.08 (16.93) | 33.45 (6.57) | 0.020 |

| Associative learning (WAIS, Letter-number sequencing) | 45.96 (18.30) | 71.00 (12.51) | 0.001 |

| Attention, working memory (WAIS, Digit span) | 18.34 (5.76) | 21.13 (3.48) | 0.057 |

| Antipsychotic medication | |||

| Chlorpromazine equivalent (mg) | 420.22 (674.48) | ||

| Atypical antipsychotics (%) | 23 (100) | ||

| Typical antipsychotics (%) | 3 (13.04) | ||

| Antidepressants (%) | 12 (52.1) | ||

| Anticonvulsants | 6 (23.08) |

Number of months between the first admission and the experiment.

2.2. Materials and procedure

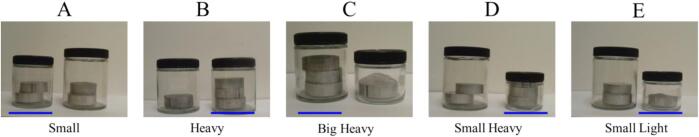

We used a sinking-object task to analyze participants' predictions and learning patterns (Castillo et al., 2015). Participants were asked to predict the behavior of transparent containers filled with aluminum discs when placed in water. Objects were pictures of transparent glass jars of different sizes (large, medium, and small) that could hold various aluminum discs. Five trial types were constituted by 12 unique jar-disc combinations with different sizes and weights (Fig. 1). A full description of this procedure can be obtained from Castillo et al. (2017).

Fig. 1.

Example pairs of objects, one for each different type of pair. The underlined object signifies the object that would sink faster in the pair. A: Small. B: Heavy. C: Big-Heavy. D: Small-Heavy. E: Small-Light trial types.

The experiment encompassed three stages. The first and last stages (pre-test and post-test) were identical, each consisting of 60 trials: Participants had to predict which of two objects would sink faster (or slower) depending on the experimental condition. The middle stage (feedback training) asked the participant to predict the sinking behavior of the jars (60 trials randomly repeated twice), but participants received feedback. After each prediction, they were shown an image of a water container in which jars were dropped (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of prediction trials in Experiments. A: Example trial during pre- or post-test. B: Example trial during feedback training.

2.3. Measures

Cognitive variables (CVs) were evaluated by subscales of the Wechsler Intelligence Test (Wechsler, 2012): processing speed (PS; Symbol search), working memory (WM; Digit span) and Associative learning (AL; Letter number sequencing). We assessed psychotic symptoms by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS, Kay and Opler, 1987).

2.4. Statistics

We split the 240-trial experimental session into four segments: pre-test (PET: Trial 1–60), training (T1: Trial 61–120, T2: Trial 121–160), and post-test (POT: Trial 161–180). We performed separate 5-by-2-by-2 ANOVAs for each segment, considering trial types, group (control vs. patients), and conditions (sink-faster vs. sink-slower) as factors (Table 2). Subsequently, we used an ANCOVA to control for the effect of CV and assess the stability of main and interaction effects before and after this control (Table 3). If these effects are still consistent, the CV impact is negligible. Lastly, we conducted a correlation analysis between CV and clinical variables (symptoms, age of illness onset, illness duration, and medication).

Table 2.

Performance (% of correct responses), patients and controls.

| Group | Controls |

Patients |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast | Slow | Fast | Slow | ||

| Pretest (PET) |

Small (S) | 0.81 (0.08) | 0.66 (0.11) | 0.59 (0.09) | 0.58 (0.10) |

| Heavy (H) | 0.94 (0.04) | 0.73 (0.12) | 0.93 (0.05) | 0.39 (0.13) | |

| Big-Heavy (BH) | 0.93 (0.04) | 0.71 (0.11) | 0.91 (0.07) | 0.43 (0.13) | |

| Small-Heavy (SH) | 0.94 (0.05) | 0.74 (0.10) | 0.92 (0.04) | 0.48 (0.09) | |

| Small-Light (SL) | 0.43 (0.01) | 0.41 (0.13) | 0.31 (0.09) | 0.67 (0.12) | |

| Training 1 (T1) |

Small (S) | 0.94 (0.03) | 0.77 (0.12) | 0.66 (0.09) | 0.48 (0.08) |

| Heavy (H) | 0.97 (0.03) | 0.70 (0.12) | 0.92 (0.05) | 0.67 (0.13) | |

| Big-Heavy (BH) | 0.93 (0.04) | 0.70 (0.10) | 0.93 (0.04) | 0.66 (0.14) | |

| Small-Heavy (SH) | 0.99 (0.01) | 0.81 (0.12) | 0.90 (0.07) | 0.72 (0.11) | |

| Small-Light (SL) | 0.64 (0.08) | 0.60 (0.08) | 0.31 (0.09) | 0.41 (0.12) | |

| Training 2 (T2) |

Small (S) | 0.92 (0.05) | 0.80 (0.13) | 0.79 (0.06) | 0.45 (0.11) |

| Heavy (H) | 0.97 (0.02) | 0.77 (0.13) | 0.89 (0.06) | 0.64 (0.14) | |

| Big-Heavy (BH) | 0.92 (0.03) | 0.69 (0.10) | 0.90 (0.04) | 0.63 (0.14) | |

| Small-Heavy (SH) | 0.99 (0.01) | 0.81 (0.12) | 0.89 (0.06) | 0.65 (0.14) | |

| Small-Light (SL) | 0.63 (0.08) | 0.75 (0.08) | 0.45 (0.10) | 0.43 (0.14) | |

| Posttest (POT) |

Small (S) | 0.95 (0.03) | 0.90 (0.09) | 0.76 (0.07) | 0.35 (0.10) |

| Heavy (H) | 0.98 ((0.02) | 0.87 (0.09) | 0.92 (0.06) | 0.46 (0.16) | |

| Big-Heavy (BH) | 0.92 (0.03) | 0.83 (0.09) | 0.90 (0.04) | 0.48 (0.15) | |

| Small-Heavy (SH) | 0.97 (0.03) | 0.89 (0.10) | 0.92 (0.05) | 0.48 (0.13) | |

| Small-Light (SL) | 0.71 (0.08) | 0.76 (0.06) | 0.40 (0.10) | 0.54 (0.13) | |

Table 3.

Main and interaction effects.

| Effects | Group F(1,41) |

Trial Type F(4,164) |

Condition F(1,41) |

Group ∗ Trial Type F(4,164) |

Group ∗ Condition F(1,41) |

Trial Type ∗ Condition F(4,164) |

Group ∗ Trial Type ∗ Condition F(4,164) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANOVA | PET | 4.79; p = .03; η2 = 0.11 | 9.17; p < .001; η2 = 0.18 | 14.54; p = .00; η2 = 0.26 | 1.29; p = .27 | 0.386; p = .54 | 7.12; p = .00; η2 = 0.15 | 3.13; p = .02; η2 = 0.07 |

| T1 | 5.57; p = .02; η2 = 0.12 | 9.17; p < .001; η2 = 0.19 | 8.05; p = .01; η2 = 0.16 | 2.86; p = .03; η2 = 0.07 | 0.038; p = .85 | 2.55; p = .04; η2 = 0.06 | 0.22; p = .93 | |

| T2 | 5.59; p = .02; η2 = 0.12 | 7.27; p = .010; η2 = 0.15 | 5.59; p = .02; η2 = 0.12 | 1.37; p = .25 | 0.60; p = .44 | 2.72; p = .03; η2 = 0.06 | 0.24; p = .92 | |

| POT | 18.69; p = .00; η2 = 0.31 | 10.01; p = .00; η2 = 0.20 | 10.01; p = .00; η2 = 0.20 | 1.89; p = .11 | 4.75; p = .04; η2 = 0.10 | 5.10; p = .01; η2 = 0.11 | 0.99; p = .42 | |

| Effects | Group F(1,37) |

Trial Type F(4,148) |

Condition F(1,37) |

Group ∗ Trial Type F(4,148) |

Group ∗ Condition F(1,37) |

Trial Type ∗ Condition F(4,148) |

Group ∗ Trial Type ∗ Condition F(4,148) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCOVA | PET | 1.52; p = .23 | 0.06; p = .99 | 16.00; p = .00; η2 = 0.30 | 0.60; p = .66 | 0.08; p = .79 | 5.84; p = .00; η2 = 0.14 | 2.48; p = .05; η2 = 0.06 |

| T1 | 0.99; p = .33 | 0.57; p = .69 | 6.09; p = .02; η2 = 0.14 | 1.37; p = .25 | 0.37; p = .55 | 2.29; p = .06 | 0.24; p = .92 | |

| T2 | 1.08; p = .31 | 0.34; p = .85 | 5.45; p = .03; η2 = 0.13 | 1.15; p = .34 | 0.16; p = .69 | 2.32; p = .06 | 0.18; p = .95 | |

| POT | 4.52; p = .04; η2 = 0.11 | 0.25; p = .91 | 7.15; p = .01; η2 = 0.16 | 1.16; p = .33 | 2.90; p = .10 | 4.76; p = .01; η2 = 0.11 | 1.88; p = .12 |

3. Results

3.1. Effect of CVs on performance

ANOVA showed main and interaction effects, with the control group consistently outperforming the FEP group in all experimental conditions.

Across the experiment, the Small-Light trial type consistently displayed lower accuracy compared to other trial types, regardless of group or experimental condition.

Accuracy was consistently lower in the slow-sinking condition than in the fast-sinking condition, regardless of participant group or trial type. A significant trial type-by-condition interaction effect showed higher accuracy in the Small-Light trial type under the slow-sinking condition. During T1, there was a group-by-trial type interaction effect, showing reduced accuracy for FEP across all trial types and reduced accuracy within the Small-Light trial type for the control group. In POT, an interaction effect between group and condition appeared. The control group showed no notable differences between conditions, while FEP had more correct responses in the fast-sinking condition.

An intricate trial type-by-group-by-condition interaction effect showed the control group performing better across all trial types in the fast-sinking condition and FEP excelling only in the Small-Light trial type under the slow-sinking condition.

Upon controlling for covariates (CVs), the significant differences among trial types across all experimental phases became non-significant. Likewise, the interaction effects involving group and trial type, as well as group and condition during T1 and POT, respectively, lost their statistical significance.

Of the observed between-group differences across the four experimental phases, only the distinction found in POT remained statistically significant. Similarly, among the interactions between trial type and condition across all four experimental phases, only those in PET and POT sustained their significance. Initially seen in PET, the group-by-trial type-condition interaction maintained its significance even after controlling for covariates. Remarkably, the differences related to experimental conditions persisted independently of covariates.

3.2. Correlations between clinical variables and CVs

We saw significant negative links between symptoms, associative learning, and working memory. Specifically, associative learning is strongly associated with most negative symptoms, some general symptoms, and one positive symptom. Working memory was correlated with specific negative symptoms and one positive symptom (see Supplementary information Table 4).

However, our study did not reveal any correlations between symptoms and other clinical factors. Additionally, no associations were found between symptoms, illness duration, or medication dosage. It's worth noting that although medication dosage was associated with processing speed, it did not exhibit significant links with symptoms.

4. Discussion

We examined first-episode schizophrenia patients and their matched controls in a reasoning-learning task where they predicted the sinking speed of objects based on prior beliefs about their physical properties. After accounting for CVs effects, we found that both patients and controls performed similarly, and their beliefs about sinking objects were independent of CVs. Furthermore, we observed better performance in the faster sinking condition and an interaction between the condition and trial type. This indicates that, regardless of group membership, different beliefs can be activated depending on instructions for predicting object sinking speed, even when the stimuli and task remain the same. Additionally, the interaction effect revealed that participants performed better in the sinking slower condition when working with the Small-Light trial type, as previously reported in healthy undergraduate students (Castillo et al., 2015, Castillo et al., 2017).

Our findings suggest that the availability of cognitive resources may explain the lower patient performance, as found in adult schizophrenia patients. Collins et al. (2014) linked impaired performance in a reinforcement learning task to working memory, while Culbreth et al. (2017) attributed deficits in a decision-making task to IQ levels and working memory. Cardella and Gangemi's (2015) review indicated that differences in reasoning tasks between patients and controls could be accounted for by IQ and cognitive abilities. Similarly, Zhu et al. (2021) found reduced cognitive flexibility in schizophrenia and depressive patients aged 18–65, with differences disappearing after controlling for IQ scores. However, caution should be exercised when comparing these findings to ours, considering differences in tasks and participant age ranges.

We observed that in patients, cognitive variables (CVs) were linked to general, positive, and negative symptoms. Therefore, the symptoms of FEP could contribute to deficits in cognitive variables and explain their lower performance compared to the control group. This assumption is based on our study not including symptom measurements in the control group.

This study has limitations. Firstly, the small sample size prevents us from drawing definitive conclusions. Secondly, we did not investigate other CVs, such as executive functioning, inhibitory control, monitoring, and perceptual inference, potentially associated with our task.

Our results indicated that performance in the sinking-object task and the patient-control differences were attributable to cognitive functioning variables. Beliefs about sinking objects remained unaffected by cognitive variables. More research is needed to dissect the specific impacts of cognitive functioning variables in various stages of our predictive task and to determine the extent to which beliefs remain independent of attentional and perceptual processes.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Matrix of Correlations among symptoms, cognitive variables (CV) and clinical variables in Experiments 1 and 2.

Financial disclosure

This work was funded by ANID – Millennium Science Initiative Program – NCS2021_081, Fondecyt de Iniciación # 11140099 and Proyecto FONDEQUIP EQM190153. Additionally, this work was funded by la Universidad de Talca through the Programa de Investigación Asociativa (PIA) en Ciencias Cognitivas (RU-158-2019).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Daniel Núñez: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Javiera Rodríguez-Delgado: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ramón D. Castillo: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. José Yupanqui: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization. Heidi Kloos: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Ramon Castillo reports financial support was provided by University of Talca Faculty of Psychology. Ramon D. Castillo reports a relationship with National Agency for Research and Development that includes: funding grants. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, RDC. The data are not publicly available due to information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

References

- Adams R.A., Napier G., Roiser J.P., Mathys C., Gillen J. Attractor-like dynamics in belief updating in schizophrenia. J. Neurosci. 2018;38(44):9471–9485. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3163-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunyé T.T., Taylor H.A. Working memory in developing and applying mental models from spatial descriptions. J. Mem. Lang. 2008;58(3):701–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardella V., Gangemi A. Reasoning in schizophrenia. Review and analysis from the cognitive perspective. Clinical. Neuropsychiatry. 2015;12(1):3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo R.D., Kloos H., Richardson M.J., Waltzer T. Beliefs as self-sustaining networks: drawing parallels between networks of ecosystems and adults’ predictions. Front. Psychol. 2015;6:1723. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo R.D., Waltzer T., Kloos H. Hands-on experience can lead to systematic mistakes: a study on adults’ understanding of sinking objects. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications. 2017;2:28. doi: 10.1186/s41235-017-0061-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A.G.E., Brown J.K., Waltz J.A., Frank M.J. Working memory contributions to reinforcement learning impairments in schizophrenia. J. Neurosci. 2014;34(41):13747–13756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0989-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland D.E., Radvansky G.A. Working memory and syllogistic reasoning. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology A: Human Experimental Psychology. 2004;57A(8):1437–1457. doi: 10.1080/02724980343000846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbreth A., Westbrook A., Daw N.D., Botvinick M., Barh D.M. Reduced model-based decision-making in schizophrenia. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2017;125(6):777–787. doi: 10.1037/abn0000164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans S.L., Averbeck B.B., Furl N. Jumping to conclusions in schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015;11:1615–1624. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S56870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firestone C., Scholl B.J. Cognition does not affect perception: evaluating the evidence for “top-down” effects. Behavioral and Brain Science. 2016;1-77 doi: 10.1017/S0140525X15000965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith C.D., Friston K.J. Neurosciences and the Human Person: New Perspectives on Human Activities Pontifical Academy of Sciences, Scripta Varia 121, Vatican City. 2013. False perceptions & false beliefs: understanding schizophrenia.www.casinapioiv.va/content/dam/accademia/pdf/sv121/sv121-frithc.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Griffin J.D., Fletcher P.C. Predictive processing, source monitoring, and psychosis. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2017;13:265–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horga G., Schatz K.C., Abi-Dargham A., Peterson B.S. J. Neurosci. 2014;34(24):8072–8082. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0200-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kail R.V., Lervåg A., Hulme C. Longitudinal evidence linking processing speed to the development of reasoning. Dev. Sci. 2016;19(6):1067–1074. doi: 10.1111/desc.12352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan C.M., Saha D., Molina J.L., et al. Brain. 2016;139:2082–2095. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay S.R., Opler L.A. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.J., Park E.H. Relationship of Working Memory, Processing Speed, and Fluid Reasoning in Psychiatric Patients. Psychiatry Investig. 2018;15(12):1154–1161. doi: 10.30773/pi.2018.10.10.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauer K.C., Musch J., Naumer B. On belief bias in syllogistic reasoning. Psychol. Rev. 2000;107(4):852–884. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.107.4.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloos H. Interlinking physical beliefs: children’s bias towards logical congruence. Cognition. 2007;103:227–252. doi: 10.1016/J.Cognition.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randers L., Møllegaard J.R., Fagerlund B., et al. Generalized neurocognitive impairment in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: the possible key role of slowed processing speed. Brain and Behavior. 2020;11 doi: 10.1002/brb3.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmack K., Gómez-Carrillo de Castro A., Rothkirch M., et al. Delusions and the role of beliefs in perceptual inference. J. Neurosci. 2013;33(34):13701–13712. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1778-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmack K., Schnack A., Priller J., Sterzer P. Perceptual instability in schizophrenia: probing predictive coding accounts of delusions with ambiguous stimuli. Schizophrenia Research: Cognition. 2015;2:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Guerrero E., Ruiz-Veguilla M., Martin-Rodríguez A., Rodríguez-Testal J.F. Inflexibility of beliefs and jumping to conclusions in active schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterzer P., Adams R.A., Fletcher P., et al. The predictive coding account of psychosis. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;84(9):634–643. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuke H., Weilnhammer V.A., Sterzer P., Schmack K. Delusion proneness is linked to a reduced usage of prior beliefs in perceptual decisions. Schizophr. Bull. 2018;45(1):80–86. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamez E., Myerson J., Hale S. Learning, working memory, and intelligence revisited. Behav. Process. 2008;78:240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teufel C., Nanay B. How to (and how not to) think about top-down influences on visual perception. Conscious. Cogn. 2017;47:17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teufel C., Subramaniam N., Dobler V., et al. Shift toward prior knowledge confers a perceptual advantage in early psychosis and psychosis-prone healthy individuals. PNAS. 2015;112(43):13401–13406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503916112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valton V., Karvelis P., Richards K.L., Seitz A.R., Laerie S.M., Series P. Acquisition of visual priors and induced hallucinations in chronic schizophrenia. Brain. 2019;0:1–15. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Vol. 2008. NCS Pearson, Inc. Edición original; Madrid: 2012. WAIS-IV. Escala de inteligencia de Wechsler para adultos-IV. Manual técnico y de interpretación. [Google Scholar]

- Zanelli J., Mollon J., Sandin S., et al. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2019;176:811–819. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18091088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C., Kwok N.T., Chan T.C., Chan G.H., So S.H. Inflexibility in reasoning: comparisons of cognitive flexibility, explanatory flexibility, and belief flexibility between schizophrenia and major depressive disorder. Front. Psych. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Matrix of Correlations among symptoms, cognitive variables (CV) and clinical variables in Experiments 1 and 2.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, RDC. The data are not publicly available due to information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.