Abstract

Introduction

Our untargeted metabolic data unveiled that Acyl-CoAs undergo dephosphorylation, however little is known about these novel metabolites and their physiology/pathology relevance.

Objectives

To understand the relationship between acyl-CoAs dephosphorylation and energy status as implied in our previous work, we seek to investigate how ischemia (energy depletion) triggers metabolic changes, specifically acyl-CoAs dephosphorylation in this work.

Methods

Rat hearts were isolated and perfused in Langendorff mode for 15 minutes followed by 0, 5, 15, and 30-minute of global ischemia. The heart tissues were harvested for metabolic analysis.

Results

As expected, ATP and phosphocreatine were significantly decreased during ischemia. Most short- and medium-chain acyl-CoAs progressively increased with ischemic time from 0 to 15 minutes, whereas 30-minute ischemia did not lead to further change. Unlike other acyl-CoAs, propionyl-CoA accumulated progressively in the hearts that underwent ischemia from 0 to 30 minutes. Progressive dephosphorylation occurred to all assayed acyl-CoAs and free CoA regardless their level changes during the ischemia.

Conclusions

The present work further confirms that dephosphorylation of acyl-CoAs is an energy-dependent process and how this dephosphorylation is mediated warrants further investigations. It is plausible that dephosphorylation of acyl CoAs and limited anaplerosis are involved in ischemic injuries to heart. Further investigations are warranted to examine the mechanisms of acyl-CoA dephosphorylation and how the dephosphorylation is possibly involved in ischemic injuries.

Keywords: myocardial ischemia, acyl-CoA, acyl-dephospho-CoA, propionyl-CoA, cardiac energy metabolism

1. Introduction

Ischemia results in numerous deleterious consequences to the myocardium. Despite significant advances in the clinic to initiate reperfusion and salvage heart tissue, ischemic heart disease remains one of the leading causes of death in the United States (Buja, 2022; Jennings, 2013; Nowbar et al., 2019).

The lack of sufficient oxygen supply during ischemia alters the utilization of energy fuels to a greater reliance on anaerobic glycolysis (Askenasy, 2001). This metabolic switch cannot fully compensate for the loss of ATP production from oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria that is necessary to sustain cardiac pump function (Ohsuzu et al., 1994). However, the depletion of ATP is not the only deleterious factor in ischemic injuries; the accumulations of acyl-CoAs due to the inhibition of fatty acid oxidation lead to a toxic detergent effect (Feuvray and Leblond, 1984). Pretreatments with L-carnitine and propionylcarnitine have been reported to improve the recovery of heart from an ischemia and reperfusion injury by removing the excess amount of acyl-CoAs and replenishing tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates through propionyl-CoA anaplerosis (Broderick et al., 2004; Paulson et al., 1984; Savic et al., 2021), although little is known about propionyl-CoA anaplerosis during ischemia.

In our previous work, we discovered that all acyl-CoAs could lose phospho-group at the 3’-ribose moiety to form acyl-dephospho-CoA (Li et al., 2014), which has recently been confirmed by others using advanced a two-dimensional LC-MS technique (Wang et al., 2017). Our data also suggested that the dephosphorylation of free CoA and acetyl-CoA might be related to the decrease of ATP level (Li et al., 2014).

In the present work, we employed our established methodology to profile the time-dependent production of acyl-dephospho-CoAs in the heart exposed to a global ischemic challenge to gather insight into the process of acyl-CoA desphosphorylation and its relationship to energy status.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents and chemicals

[2H9]L-carnitine and creatine (methyl-D3) were from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Tewksbury, MA). All other chemicals including acyl-CoAs, dephospho-CoA, and acylcarnitines were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

2.2. Heart perfusions

All animal protocols were approved by the IACUC Committee of Duke University. Fed rats (~220 g, Sprague Dawley Rat, Charles River Laboratories) were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane, hearts were quickly excised and the isolated hearts were perfused in the Langendorff mode at 37°C with a non-recirculating perfusate or Krebs-Ringer buffer containing 11 mM glucose, 0.4 mM palmitate, 3% dialyzed bovine serum albumin (fraction V, fatty acid-free; InterGen), 100 μU/ml insulin, and 0.05 mM L-carnitine at a constant flow rate of 12 ml/minute (Li et al., 2015). The hearts were allowed to beat spontaneously throughout the perfusion. The hearts were perfused for 15 minutes to establish baseline function, followed by stop-flow ischemia for 0, 5, 15, and 30 minutes. Hearts were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at a −80 °C freezer until further analysis.

2.3. Acyl-CoAs, acyl-dephospho-CoAs, AMP, ADP, and ATP profiled by LC-MS/MS

Acyl-CoAs, ATP, ADP, and AMP were analyzed based on our previously established method (Zhang et al., 2009). Briefly, a ~100 mg heart tissue was spiked with 0.2 nmol internal standard ([2,2,3,3,4,4,5,5,5-2H9]pentanoyl-CoA) and homogenized in 3 ml of extraction buffer (5% acetic acid in MeOH/H2O 50:50) using a Tissuelyser (Qiagen). The supernatant was run on a 3 ml ion exchange cartridge packed with 300 mg of 2–2(pyridyl)ethyl silica gel (Sigma). The cartridge was pre-activated with 3 ml methanol, and then equilibrated with 3 ml of extraction buffer. The acyl-CoAs trapped on the silica gel cartridge were eluted with (i) 3 ml of a 1:1 mixture of 50 mM ammonium formate (pH 6.3), and methanol, then (ii) 3 ml of a 1:3 mixture of 50 mM ammonium formate (pH 6.3) and methanol, and (iii) 3 ml of methanol. The combined effluent was dried with N2 gas and stored at −80°C until LC-MS/MS analysis. The dried sample was used for all assays by an UHPLC-QTRAP-6500+-MS/MS.

2.4. Creatine (Cr) and phosphocreatine (P-Cr) quantitation by LC-MS/MS

Cr and P-Cr were analyzed with the modified LC-MS/MS method (Wang et al., 2014). A ~10 mg heart tissue was spiked with internal standard (0.2 nmol D3 Cr and 0.2 nmol D3 P-Cr) and was homogenized in 400 μl methanol followed by adding 400 μl distilled H2O and 400 μl chloroform using a Tissuelyser (Qiagen). The homogenized sample was centrifuged for 15 minutes at 13000×g for 15 minutes and the upper phase extract (700 μl) was dried completely by nitrogen gas. The sample was re-suspended into 100 μl distilled H2O for UHPLC-QTRAP-6500+-MS/MS analysis. The detailed LC-MS/MS method can be found in our previous report (Wang et al., 2014).

2.5. LC-MS/MS for acylcarnitine profile

Acylcarnitine in cardiac tissue was methylated and profiled by a modified LC-MS/MS method (Millington and Stevens, 2011). Powdered cardiac tissue samples (~20 mg) were spiked with 0.2 nmol [2H9]L-carnitine as an internal standard. The extracted samples were methylated with 3 M HCl methanol solution (100 μl). The derivatized samples were analyzed by an LC-QTRAP 6500+-MS/MS (Sciex, Concord, Ontario) (Millington and Stevens, 2011; Wang et al., 2018).

2.6. GC-MS for metabolite profile

Metabolic changes in heart tissue were profiled by our published GC-MS method (Wang et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2021). Briefly, ~20 mg heart was spiked with 0.1 nmol norvaline as an internal standard and extracted via the standard Folch extraction (Folch et al., 1957). The upper phase, ~400 μl, was transferred to a new Eppendorf vial and dried with nitrogen gas. The dried residues were derivatized with methoxylamine hydrochloride and N-tert-butyldimethylsilyl-N-methyltrifluoroacetamide (TBDMS) sequentially. Specifically, 40 μl of methoxylamine hydrochloride (2% (w/v) in pyridine) was added to the dried residues and was incubated for 90 minutes at 40°C followed by adding 20 μL of TBDMS with 1% tert-butylchlorodimethylsilane and incubating for 30 minutes at 80°C. The samples were then centrifuged for 10 minutes at 12,000 × g and the supernatants of derivatized samples were transferred to GC vials for further analysis. GC/MS analysis was conducted as previously described using an Agilent 7890B GC system with an Agilent 5977A Mass Spectrometer. Specifically, 1 μl of the derivatized sample was injected into the GC column. The GC temperature gradient started at 80°C for 2 minutes, increased to 280°C at the speed of 7°C per minute, and held at 280°C until the completion of a run time of 40 minutes. The ionization was conducted by electron impact (EI) at 70 eV with Helium flow at 1 mL/min. Temperatures of the source, the MS quadrupole, the interface, and the inlet were maintained at 230°C, 150°C, 280°C, and 250°C, respectively. Mass spectra (m/z) from 50 to 700 were recorded in mass scan mode.

2.7. Statistics

Statistical differences were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett post-hoc test using Prism (GraphPad) software. The student’s t test was performed when two groups were compared.

3. Results

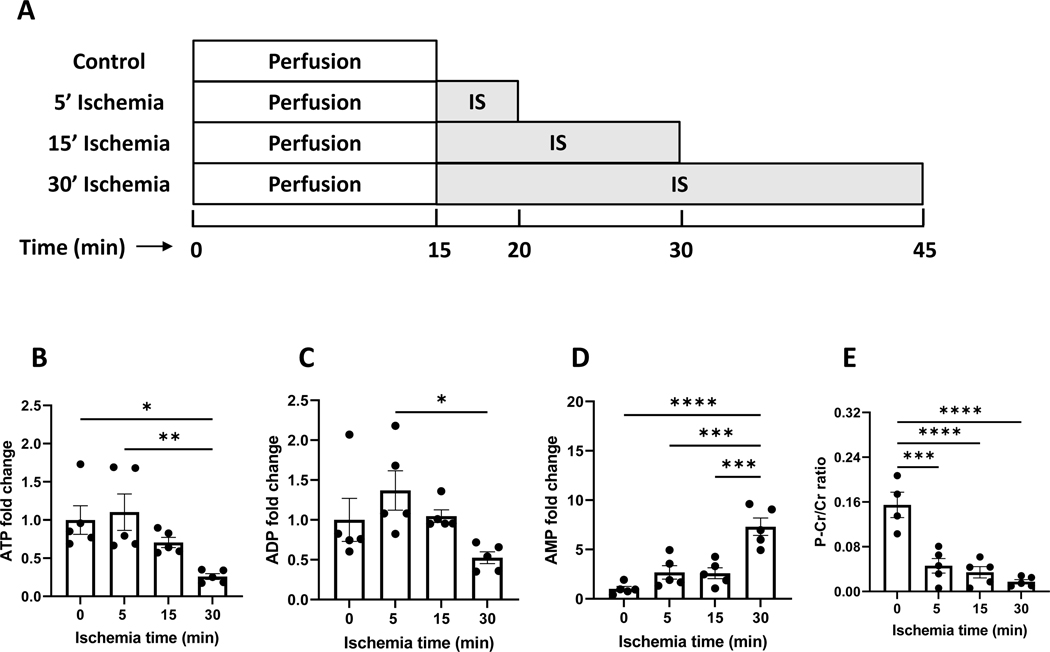

3.1. Cardiac energy is progressively depleted with ischemia

Following an equilibration, spontaneously beating hearts were subjected to a stop-flow ischemia ranging from 0 to 30 minutes as shown in Fig. 1A. As expected, the perfused rat hearts drained energy progressively with the ischemia. The primary indices of cellular energy status, i.e. ATP, ADP, AMP, and phosphocreatine/creatine ratio, were measured and are shown in Figs 1B–1E. ATP was progressively decreased to 25% after 30 minutes of ischemia. AMP was correspondingly elevated to 7.4-fold. The ratio of P-Cr/Cr dropped by ~10-fold. These data confirmed the energy depletion over the course of ischemia.

Figure 1. Energy depletion occurred in the ischemic heart.

A is the experimental design of ischemia in the perfused rat hearts. After 15 min pre-conditioning with Krebs-Ringer buffer perfusate, rat hearts were subjected to ischemia from 0–30 minutes. B-E are relative changes in ATP, ADP, AMP levels, and P-Cr/Cr ratio due to ischemia. IS: ischemia, P-Cr: phosphocreatine, Cr: creatine. N=5 per group. *, **, ***, and **** refers to p<0.05, 0.01, 0.005, and 0.001, respectively. Error bar is SEM.

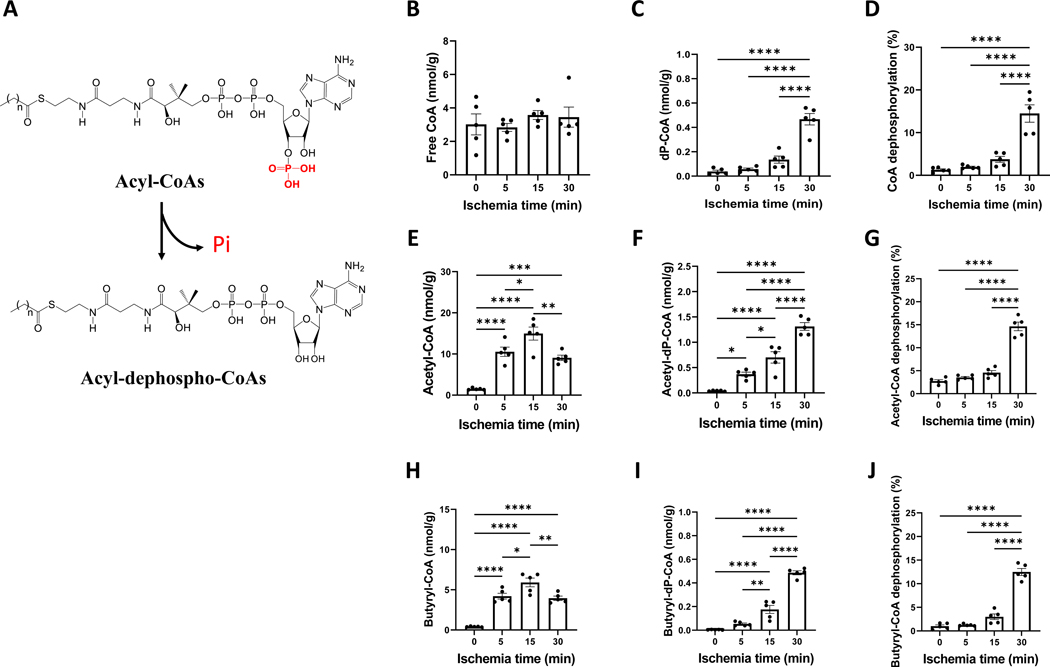

3.2. The dephosphorylation of acyl-CoAs increased with ischemia in the perfused hearts

After we discovered acyl-CoA dephosphorylation, as illustrated in Fig. 2A, we attempted to uncover more about this novel metabolite and how dephosphorylation relates to energy status. The level of free CoA was not significantly different in the control and ischemic hearts at any time points from 5 to 30 minutes (Fig. 2B). However, dephospho-CoA consistently increased with the ischemic time (Fig. 2C). Free CoA dephosphorylation increased from 1.3% to 14.5% (Fig. 2D). Acetyl-CoA progressively went up in the hearts exposed to 5, 10, and 15 minutes of ischemia (Fig. 2E), but then dropped at 30 minutes. Acetyl-dephospho-CoA increased with ischemic time regardless of acetyl-CoA changes (Fig. 2F). Similar to free CoA dephosphorylation, the dephosphorylation rate of acetyl-CoA increased to 14.7% after 30 minutes of ischemia (Fig. 2G).

Figure 2. Acyl-CoAs and their dephoshphorylation in the ischemic heart.

A is the scheme of the conversion of acyl-CoAs to acyl-dephospho-CoAs by losing phosphor-group at the 3’-ribose moiety. B-J are the changes of free CoA, acetyl-CoA, butyryl-CoA, their corresponding acyl-dephospho-CoAs, and phosphorylation in the perfused rat hearts that underwent ischemia from 0 to 30 minutes. The concentration unit (nmol/g) was based on tissue wet weight. N=5 per group. *, **, ***, and **** refers to p<0.05, 0.01, 0.005, and 0.001, respectively. Error bar is SEM.

Several other short- and medium-chain acyl-CoAs showed the similar dephosphorylation patterns as acetyl-CoA (Figs. 2H–2J, Supplementary Fig. 1). The dephosphorylation of other acyl-CoAs ranged from 8 to 12.5%, with the exception of decanoyl-CoA (58%) which may be due to the limit of detection and the inaccuracy of measurement. The dephosphorylated acyl-CoAs with C>10 (the carbon chain length) were not detectable due to their low acyl-CoA levels.

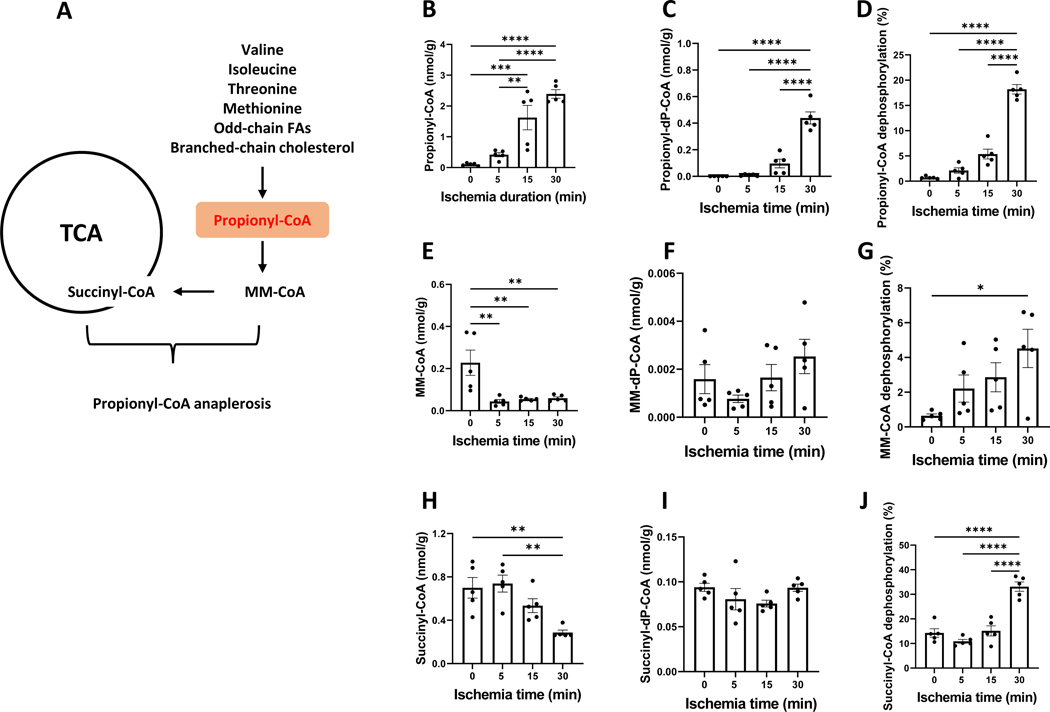

3.3. Propionyl-CoA was accumulated in the ischemic heart

Propionyl-CoA is not derived from glucose or even-chain fatty acids; it is a metabolite derived from amino acids, odd-chain fatty acids and propionate. Propionyl-CoA is a good anaplerotic substrate as depicted in Fig. 3A. Propionyl-CoA carboxylation to methylmalonyl-CoA (MM-CoA) is catalyzed by propionyl-CoA carboxylase and is an ATP-consuming step. Unlike other saturated acyl-CoAs, propionyl-CoA surprisingly increased over the 30-minute global ischemia (Fig. 3B) reaching ~23-fold increase at 30 minutes. The dephosphorylation of propionyl-CoA was also observed (Fig. 3C). Propionyl-CoA dephosphorylation increased from 0.7% to 18% over the 30-minute ischemia (Fig. 3D). In contrast, MM-CoA, the downstream metabolite of propionyl-CoA, was dramatically decreased (Fig. 3E). A 5-minute ischemia sharply decreased MM-CoA by 5 folds without any further change during the 30-minute ischemia. However, the dephosphorylation of MM-CoA continuously increased over 30 minutes of ischemia (Figs. 3F and 3G). Succinyl-CoA is the metabolic product derived from both MM-CoA and 2-ketoglutarate. A 5-minute ischemia did not significantly alter succinyl-CoA concentration. However, a prolonged ischemia (30 minutes) resulted in a reduced succinyl-CoA (<50%) (Fig. 3H) and an unchanged succinyl-dephospho-CoA (Fig. 3I). The dephosphorylation rate of succinyl-CoA was significantly increased after a 30-minute ischemia (Fig. 3J).

Figure 3. Propionyl-CoA anaplerosis is inhibited in the ischemic heart.

A is propionyl-CoA metabolism including its anaplerosis to TCA cycle and the synthesis from amino acids, odd-chain fatty acids (FAs) and branched-chain cholesterol. B-J are propionyl-CoA, methylmalonyl-CoA (MM-CoA), succinyl-CoA, their corresponding acyl-dephospho-CoAs, and phosphorylation in the perfused rat hearts that underwent ischemia from 0 to 30 minutes. N=5 per group. The concentration unit (nmol/g) was based on tissue wet weight. *, **, ***, and **** refers to p<0.05, 0.01, 0.005, and 0.001, respectively. Error bar is SEM.

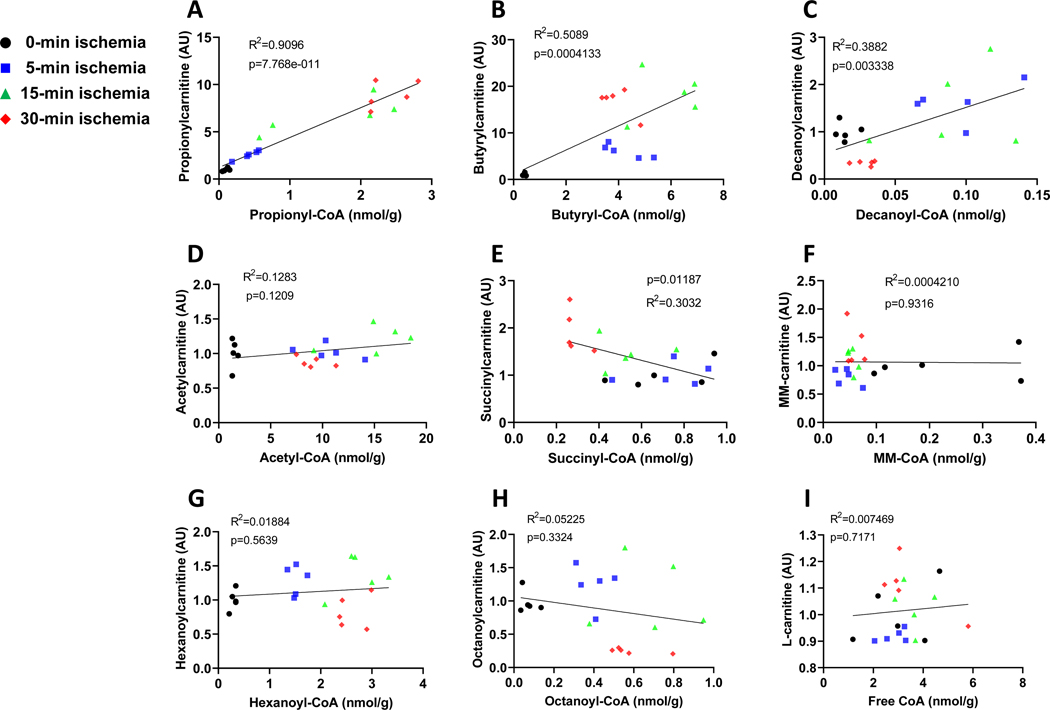

Acyl-CoAs are intracellular metabolites and can be converted to their corresponding acylcarnitines by carnitine acyltransferases. The alterations of acyl-CoAs and their dephosphorylation in the ischemic heart could potentially impact the acylcarnitine pool, thus we profiled acylcarnitines. Most acylcarnitines demonstrated the similar changes as their corresponding acyl-CoAs except acetylcarnitine, methylmalonylcarnitine (MM-carnitine), and succinylcarnitine (Figs. 4 and supplementary Fig. 2), which remained largely unchanged throughout a 30-minute ischemia (Supplementary Fig. 2). Overall, it appeared that the changes of both dicarboxylylcarnitines (succinylcarnitine and MM-Carnitine) did not respond to the changes of their respective dicarboxylyl-CoAs.

Figure 4. The correlation between acylcarnitine and acyl-CoAs.

A-I are the correlation between acyl-CoAs and their corresponding acylcarnitines including propionylcarnitine, butyrylcarnitine, decanylcarntine, acetylcarntine, succinylcarnitine, methylmalonylcarnitine (MM-carnitine), hexanoylcarnitine, octanoylcarnitine, and l-carntine, in the perfused rat hearts that underwent ischemia from 0 to 30 minutes. N=5 per group.

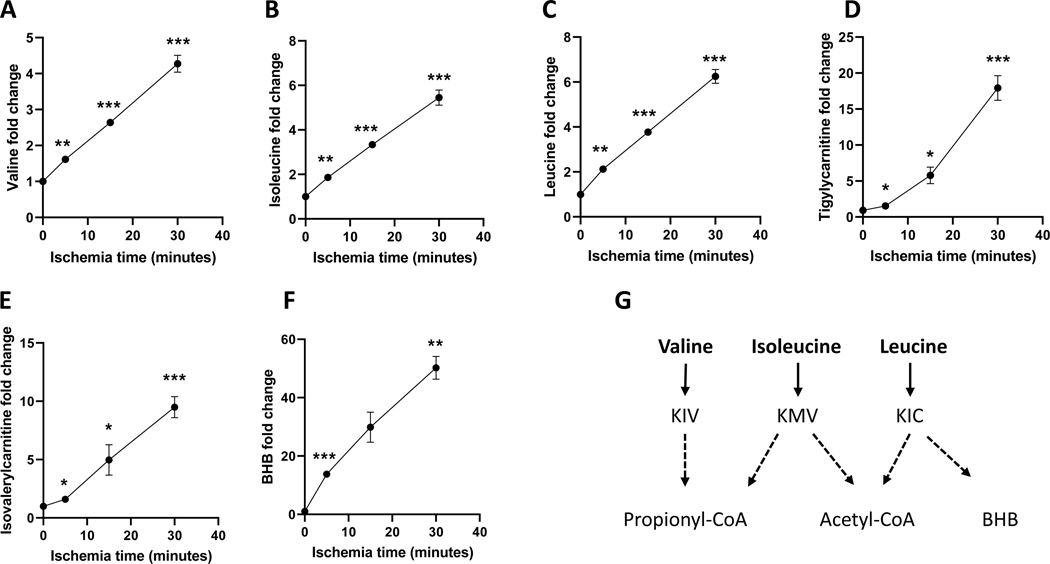

The accumulation of propionyl-CoA could rewire the metabolism of propionyl-CoA-related substrates. Valine and isoleucine are the major metabolic substrates of propionyl-CoA (Fig. 3A). Propionyl-CoA metabolic substrates, their metabolic intermediates, and other metabolites in the control and ischemic hearts were profiled (Supplementary Table 1). Interestingly, both valine and isoleucine are substantially increased with the ischemic time but not threonine and methionine (Figs. 5A and 5B and Supplementary Table 1). Tiglylcarnitine and 3-hydroxyisobutyrate, the catabolites of isoleucine and valine, were also significantly increased in the ischemic hearts (Fig. 5D). Valine and isoleucine are branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs). The inhibition of BCAAs metabolism was also evidenced by the increased leucine in the ischemic heart (Fig. 5C). Inhibition of leucine (ketogenic amino acid) catabolism was demonstrated by the accumulations of isovalerylcarnitine (Fig. 5E) and 3-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) (Fig. 5F). High NADH and accumulated succinate (Supplementary Table 1) might inhibit BHB metabolism and further leucine catabolism in a similar way as valine and isoleucine metabolism to propionyl-CoA. The relevant metabolism of BCAAs was outlined in Fig. 5G.

Figure 5. The metabolic changes of branched-chain amino acids in the ischemic hearts.

A-F are valine, isoleucine, leucine, tigylycarnitine, isovalerylcarnitine, 3-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) in the perfused hearts that underwent ischemia from 0 to 30 minutes. N=5 per group. *, **, ***, and **** refers to p<0.05, 0.01, 0.005, and 0.001, respectively. The statistic analysis was performed by comparing the metabolite at each ischemic time to the control with Student’s t-test. Error bar is SEM.

4. Conclusions

Ischemic insult to the heart is a common clinical complication and identifying the underlying mechanisms is key to formulating new therapies. The phosphorylation is the second to last step in the synthetic pathway of coenzyme A (Srinivasan et al., 2015), catalyzed by dephospho-CoA kinase. Conversely, CoA can be dephosphorylated to dephospho-CoA. Valproyl-dephospho-CoA was identified as a novel metabolite of valproate (Silva et al., 2004). We previously identified endogenous acyl-dephospho-CoAs in several tissues using a high resolution mass spectrometry implying that the moieties possess biological activity, likely related to oxygen level or energy status (Li et al., 2014). A low ATP in the brain and kidney was positively correlated to the dephosphorylation levels of acyl-CoAs. In this study, we expanded our investigation to a pathophysiological model of the heart to evaluate the dephosphorylation of acyl-CoAs during an ischemic insult.

The suspension of aerobic metabolism after the depletion of oxygen resulted in accumulations of numerous acyl-CoAs from 0–15 minutes, followed by a decrease likely due to the inhibition of fatty acid oxidation and pyruvate dehydrogenase. Interestingly, propionyl-CoA, unlike other acyl-CoAs, continuously accumulated throughout the 30 minutes of ischemia. The major metabolic sources of propionyl-CoA are from amino acids and propionate. Propionyl-CoA is unlikely derived from odd-chained fatty acid oxidation due to (i) the trace amount of odd-chained fatty acids in the heart and (ii) the contrasting change of propionyl-CoA mediated by the ischemia as compared to butyryl-CoA and hexanoyl-CoA (formed during fatty acid catabolism). In our study, the accumulations of BCAAs could also be the result of proteolysis since they are essential amino acids and were absent in the perfusate. However, their catabolism is apparently inhibited at the propionyl-CoA carboxylation step based on their elevated downstream metabolites (3-hydroxyisobutyrate, tiglylcarnitine, and propionyl-CoA) and a sharp drop of MM-CoA. Similarly, the accumulations of leucine and its downstream metabolites, isovalerylcarnitine and BHB, also suggest the inhibited BCAAs catabolism in the ischemic heart. BHB was not in perfusate and the general process of ketone release is from the liver (Deng et al., 2009; Newman and Verdin, 2017). The increased BHB production in the ischemic heart through beta-hydroxy-beta-methylglutaryl (HMG)-CoA synthase was also observed by Lindsay et al (Lindsay et al., 2021). The elevation of BHB could also be due to the reduced BHB metabolism in the ischemic heart given the fact that succinate went up (Supplementary Table 1).

The accumulation of propionyl-CoA is likely due to the inhibition of propionyl-CoA carboxylation to MM-CoA (an ATP-dependent process). This may explain why propionyl-CoA progressively accumulates over a 30-minute ischemia. Propionylcarnitine followed the change of propionyl-CoA, suggesting that carnitine acetyltransferase (CrAT) is highly active in heart (Marquis and Fritz, 1965) and is not affected by the ischemia. The low carboxylation of propionyl-CoA due to the depletion of ATP is also supported by the significant drop of MM-CoA at 5 minutes of ischemia. Succinyl-CoA also decreased but at a lower rate compared to MM-CoA since succinyl-CoA can also be generated from 2-ketoglutarate in TCA cycle. Interestingly, the changes of succinylcarnitine and MM-Carnitine were not correlated with their counterparts, i.e., succinyl-CoA and MM-CoA. This suggests a low conversion rate of short-chain dicarboxylyl-CoAs to dicarboxylylcarnitines (Kerner et al., 2014). Dicarboxylylcarnitines were recently reported as the biomarkers of heart failure (Shah et al., 2012), however, the relevance of short-chain (C3 and C4) dicarboxylylcarnitines to heart failure remains to be investigated and the isomers of acylcarnitine remain to be further separated and identified (Ruiz et al., 2017).

The changes in propionyl-CoA, MM-CoA, and succinyl-CoA suggest that energy storage is quickly depleted in the perfused hearts during ischemia. This was evidenced by the direct measurement of ATP, ADP, AMP, and the ratio of PCr/Cr. The present work demonstrates a strong correlation between the dephosphorylation of all assayed acyl-CoAs and the ischemic time regardless of the changes of their concentrations. Furthermore, our pilot study showed that the dephosphorylated acyl-CoAs were re-phosphorylated back to pre-ischemic level after 5–15 minutes of reperfusion (data not shown). This again suggested that acyl-CoA dephosphorylation is associated with the energy status. Our initial experiments excluded the non-enzymatic dephosphorylation of acyl-CoAs (data not shown). This novel finding raises several questions about the physiological and pathological roles of the dephosphorylation of acyl-CoAs. The dephosphorylation of acyl-CoAs could be due to the low activity of the ATP-dependent dephospho-CoA kinase during the ischemia. The increased dephospho-CoA may be used to synthesize acyl-dephospho-CoAs, though a high rate of incorporation is questionable. The second possibility is the existence of a novel and an ischemia-activated phosphatase to dephosphorylate acyl-CoAs. The third possibility is that the energetic deficit of the ischemic heart drives acyl-CoA dephosphorylation to release energy, like the process of ATP to ADP and AMP.

Although the dephosphorylation is clearly associated with energy status as shown in the present work, the following study limitations of this work are also appreciated: (1) the isolated heart perfusion is a simple model for ischemia manipulation. However, the data of isolated heart perfusion might not represent exactly what occurs in in vivo; (2) acyl-CoA dephosphorylation increases progressively with the ischemic time from 0 to 30 minutes. However, the 30-minute global ischemia is a severe insult causing major injuries and even cell death, which might be not a good study model of pathology; (3) the interpretation of propionyl-CoA and BCAA metabolism are based on the metabolic profile data. The stable isotope tracing study is needed to further confirm the relationship between energy deficit and propionyl-CoA/BCAAs metabolism in the ischemic heart. Future studies will investigate the mechanism of acyl-dephospho-CoAs formation and then their physiological and pathological roles.

In summary, the suggested mechanism is outlined in Fig. 6. Observed energy deficiency under ischemia contributes to the restricted propionyl-CoA anaplerosis. Suggestively, the energy deficiency leads to the dephosphorylation of acyl-CoAs and free CoA. This novel finding warrants further investigation into the relevance of the dephosphorylation to ischemic injuries.

Figure 6. The scheme of acyl-CoA dephosphorylation and propionyl-CoA accumulation in the ischemic heart.

The scheme summarizes the dephosphorylation of acyl-CoA and other metabolic disturbances in the ischemic heart when ATP is depleted. FA: fatty acid, Acyl-CoA: acyl coenzyme A, TCA: tricarboxylic acid cycle, MM-CoA: methylmalonyl-CoA, BCAA: branched-chain amino acid.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by AHA award 12GRNT12050453 to G.F.Z.

Footnotes

Declarations

S.F.P. is currently employed by and owns stock in Merck.

References

- Askenasy N. (2001) Glycolysis protects sarcolemmal membrane integrity during total ischemia in the rat heart. Basic Res Cardiol 96, 612–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick TL, Paulson DJ and Gillis M. (2004) Effects of propionyl-carnitine on mitochondrial respiration and post-ischaemic cardiac function in the ischaemic underperfused diabetic rat heart. Drugs R D 5, 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buja LM (2022) Pathobiology of Myocardial Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury: Models, Modes, Molecular Mechanisms, Modulation and Clinical Applications. Cardiol Rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S, Zhang GF, Kasumov T, Roe CR and Brunengraber H. (2009) Interrelations between C4 ketogenesis, C5 ketogenesis, and anaplerosis in the perfused rat liver. J Biol Chem 284, 27799–27807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuvray D. and Leblond Y. (1984) Metabolism of long chain fatty acids in the normal and pathologic heart: effects of ischemia. Diabete Metab 10, 316–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M. and Sloane Stanley GH (1957) A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem 226, 497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings RB (2013) Historical perspective on the pathology of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ Res 113, 428–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerner J, Minkler PE, Lesnefsky EJ and Hoppel CL (2014) Fatty acid chain elongation in palmitate-perfused working rat heart: mitochondrial acetyl-CoA is the source of two-carbon units for chain elongation. J Biol Chem 289, 10223–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Deng S, Ibarra RA, Anderson VE, Brunengraber H. and Zhang GF (2015) Multiple mass isotopomer tracing of acetyl-CoA metabolism in Langendorff-perfused rat hearts: channeling of acetyl-CoA from pyruvate dehydrogenase to carnitine acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem 290, 8121–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zhang S, Berthiaume JM, Simons B. and Zhang GF (2014) Novel approach in LC-MS/MS using MRM to generate a full profile of acyl-CoAs: discovery of acyl-dephospho-CoAs. J Lipid Res 55, 592–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay RT, Dieckmann S, Krzyzanska D, Manetta-Jones D, West JA, Castro C, Griffin JL and Murray AJ (2021) beta-hydroxybutyrate accumulates in the rat heart during low-flow ischaemia with implications for functional recovery. Elife 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis NR and Fritz IB (1965) The Distribution of Carnitine, Acetylcarnitine, and Carnitine Acetyltransferase in Rat Tissues. J Biol Chem 240, 2193–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millington DS and Stevens RD (2011) Acylcarnitines: analysis in plasma and whole blood using tandem mass spectrometry. Methods Mol Biol 708, 55–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman JC and Verdin E. (2017) beta-Hydroxybutyrate: A Signaling Metabolite. Annu Rev Nutr 37, 51–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowbar AN, Gitto M, Howard JP, Francis DP and Al-Lamee R. (2019) Mortality From Ischemic Heart Disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 12, e005375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsuzu F, Bessho M, Yanagida S, Sakata N, Takayama E. and Nakamura H. (1994) Comparative measurement of myocardial ATP and creatine phosphate by two chemical extraction methods and 31P-NMR spectroscopy. J Mol Cell Cardiol 26, 203–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson DJ, Schmidt MJ, Traxler JS, Ramacci MT and Shug AL (1984) Improvement of myocardial function in diabetic rats after treatment with L-carnitine. Metabolism 33, 358–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz M, Labarthe F, Fortier A, Bouchard B, Thompson Legault J, Bolduc V, Rigal O, Chen J, Ducharme A, Crawford PA, Tardif JC and Des Rosiers C. (2017) Circulating acylcarnitine profile in human heart failure: a surrogate of fatty acid metabolic dysregulation in mitochondria and beyond. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 313, H768–H781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savic D, Ball V, Curtis MK, Sousa Fialho MDL, Timm KN, Hauton D, West J, Griffin J, Heather LC and Tyler DJ (2021) L-Carnitine Stimulates In Vivo Carbohydrate Metabolism in the Type 1 Diabetic Heart as Demonstrated by Hyperpolarized MRI. Metabolites 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AA, Craig DM, Sebek JK, Haynes C, Stevens RC, Muehlbauer MJ, Granger CB, Hauser ER, Newby LK, Newgard CB, Kraus WE, Hughes GC and Shah SH (2012) Metabolic profiles predict adverse events after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 143, 873–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva MF, Ijlst L, Allers P, Jakobs C, Duran M, de Almeida IT and Wanders RJ (2004) Valproyl-dephosphoCoA: a novel metabolite of valproate formed in vitro in rat liver mitochondria. Drug Metab Dispos 32, 1304–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan B, Baratashvili M, van der Zwaag M, Kanon B, Colombelli C, Lambrechts RA, Schaap O, Nollen EA, Podgorsek A, Kosec G, Petkovic H, Hayflick S, Tiranti V, Reijngoud DJ, Grzeschik NA and Sibon OC (2015) Extracellular 4’-phosphopantetheine is a source for intracellular coenzyme A synthesis. Nat Chem Biol 11, 784–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JM, Chu Y, Li W, Wang XY, Guo JH, Yan LL, Ma XH, Ma YL, Yin QH and Liu CX (2014) Simultaneous determination of creatine phosphate, creatine and 12 nucleotides in rat heart by LC-MS/MS. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 958, 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wang Z, Zhou L, Shi X. and Xu G. (2017) Comprehensive Analysis of Short-, Medium-, and Long-Chain Acyl-Coenzyme A by Online Two-Dimensional Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem 89, 12902–12908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Christopher BA, Wilson KA, Muoio D, McGarrah RW, Brunengraber H. and Zhang GF (2018) Propionate-induced changes in cardiac metabolism, notably CoA trapping, are not altered by l-carnitine. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 315, E622–E633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang GF, Jensen MV, Gray SM, El K, Wang Y, Lu D, Becker TC, Campbell JE and Newgard CB (2021) Reductive TCA cycle metabolism fuels glutamine- and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Cell Metab 33, 804–817 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang GF, Kombu RS, Kasumov T, Han Y, Sadhukhan S, Zhang J, Sayre LM, Ray D, Gibson KM, Anderson VA, Tochtrop GP and Brunengraber H. (2009) Catabolism of 4-hydroxyacids and 4-hydroxynonenal via 4-hydroxy-4-phosphoacyl-CoAs. J Biol Chem 284, 33521–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.