Abstract

Purpose

To determine if disparities exist in survivorship care experiences among older breast cancer survivors by breast cancer characteristics, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors.

Methods

A total of 19,017 female breast cancer survivors (≥ 65 at post-diagnosis survey) contributed data via SEER-CAHPS data linkage (2000–2019). Analyses included overall and stratified multivariable linear regression to estimate beta (β) coefficients and standard errors (SE) to identify relationships between clinical cancer characteristics and survivorship care experiences.

Results

Minority survivors were mostly non-Hispanic (NH)-Black (8.1%) or NH-Asian (6.5%). Survivors were 76.3 years (SD = 7.14) at CAHPS survey and were 6.10 years (SD = 3.51) post-diagnosis on average. Survivors with regional breast cancer vs. localized at diagnosis (β = 1.00, SE = 0.46, p = 0.03) or treated with chemotherapy vs. no chemotherapy/unknown (β = 1.05, SE = 0.48, p = 0.03) reported higher mean scores for Getting Needed Care. Results were similar for Overall Care Ratings (β = 0.87, SE = 0.38, p = 0.02) among women treated with chemotherapy. Conversely, women diagnosed with distant breast cancer vs. localized reported lower mean scores for Physician Communication (β = − 1.94, SE = 0.92, p = 0.03). Race/ethnicity, education, and area-level poverty significantly modified several associations between stage, estrogen receptor status, treatments, and various CAHPS outcomes.

Conclusion

These study findings can be used to inform survivorship care providers treating women diagnosed with more advanced stage and aggressive disease. The disparities we observed among minority groups and by socioeconomic status should be further evaluated in future research as these interactions could impact long-term outcomes, including survival.

Keywords: Breast cancer, SEER-CAHPS, Socioeconomic disparities, Cancer survivorship, Older women

Introduction

According to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) [1], there are more than 3.8 million breast cancer survivors in the United States (US), with this number only expected to increase. In 2019, it is estimated that 60% of these survivors are over the age of 65 at the time of initial breast cancer diagnosis [2]. Breast cancer mortality rates have decreased across all racial and ethnic groups since 1988; however, breast cancer-specific deaths for women were highest among Asian/Pacific Islander (5.6%), non-Hispanic Black (NHB) (4.5%), and Hispanic (4.4%) women [3].

A recent study found US minority women were 24% more likely to be diagnosed with advanced stage breast cancer (regional or distant) compared to non-Hispanic white (NHW) women, and therefore, are more likely to die from their cancer [4]. More specifically, NHB women are more likely to experience triple-negative breast cancer (estrogen receptor [ER]−, progesterone receptor [PR]−, and HER2−), which grows and spreads faster and has limited treatment options [5]. As minority women are more likely to experience more advanced stages and more aggressive types of breast cancer at diagnosis [6], they also experience lower levels of appropriate therapies, such as radiation and chemotherapy treatments [7]. Time from oncology consultation to start of treatment was greater than three months for 22.4% of Black women versus 14.3% of NHW women in one study, while another reported that 10% of minority women waiting ≥ 60 days to initiate treatment [8]. Minority women were more likely to begin chemotherapy and radiation during later stages and were more likely to become nonadherent [7], which also increases the chance of worsened disease and breast cancer-specific mortality and morbidity [6].

Considering these disparities, focus has shifted to quality of care for breast cancer survivors, and more specifically, among those of minority and other hard-to-reach groups. Racial/ethnic differences in breast cancer survivorship care quality remains an intersectional and multilevel problem. Women with more aggressive tumors may involve more intensive treatments and therefore, may indicate more long-term treatment. In a study of older breast cancer survivors, minority women reported poor communication and care coordination, especially once active treatment has concluded, resulting in increased frustration and confusion concerning survivorship care and engagement in their own ongoing care [9, 10]. The combination of neglect and potential treatment side effects may also affect post-treatment quality of care perceptions, where those with chemotherapy, for instance, have trouble concentrating on future directions and care coordination both during and after treatment [9]. It has also been reported that the transition from active treatment to survivorship can be damaging, as care not only from physicians and specialists, but also from family and friends, seems to drop suddenly upon completion of treatment [11].

Socioeconomic position also impacts the quality of care and likelihood of survival, as quality of care, both during treatment and afterward, depends on financial and physical access including barriers to treatment due to transportation, residential locale, time, and difficulty navigating the healthcare system and multiple specialists [12]. Disparities exist in treatment availability and options, especially for those living in rural locations [13] and timeliness of initial treatment [14]. Some research has suggested that physician communication plays a role, but patient access to treatment centers, patient preference, and out-of-pocket costs of treatment may directly impact the quality of survivorship care [15]. Impoverished women, as one study has found, were less likely than women living outside of poverty, to receive appropriate breast cancer treatment, such as radiation after breast-conserving surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy, and long-term tamoxifen use [16]. In other studies, education and residential locale were associated with reduced doses of chemotherapy [17]. Quality of care and related disparities in breast cancer treatment and survivorship, therefore, is defined by more than just patient-provider communication, but is also intersectional, relying on biological, social, institutional, and socioeconomic factors that exist long after treatment has ended.

Objectives.

Our study utilized the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) Consumer Assessment for Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) data linkage from 2000 to 2019 to examine the associations between tumor characteristics, breast cancer treatments, and experienced quality of survivorship care post-primary breast cancer diagnosis among older (≥ 65 years) female survivors in the US. Associations were also stratified by race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors, including area-level poverty, education, and Medicare plan types to identify potential disparities among vulnerable groups. Therefore, the current analysis aims at identifying care experience quality gaps to inform providers as well as future interventions and policy to reduce disparities in breast cancer survivorship.

Materials & methods

Study design & sample

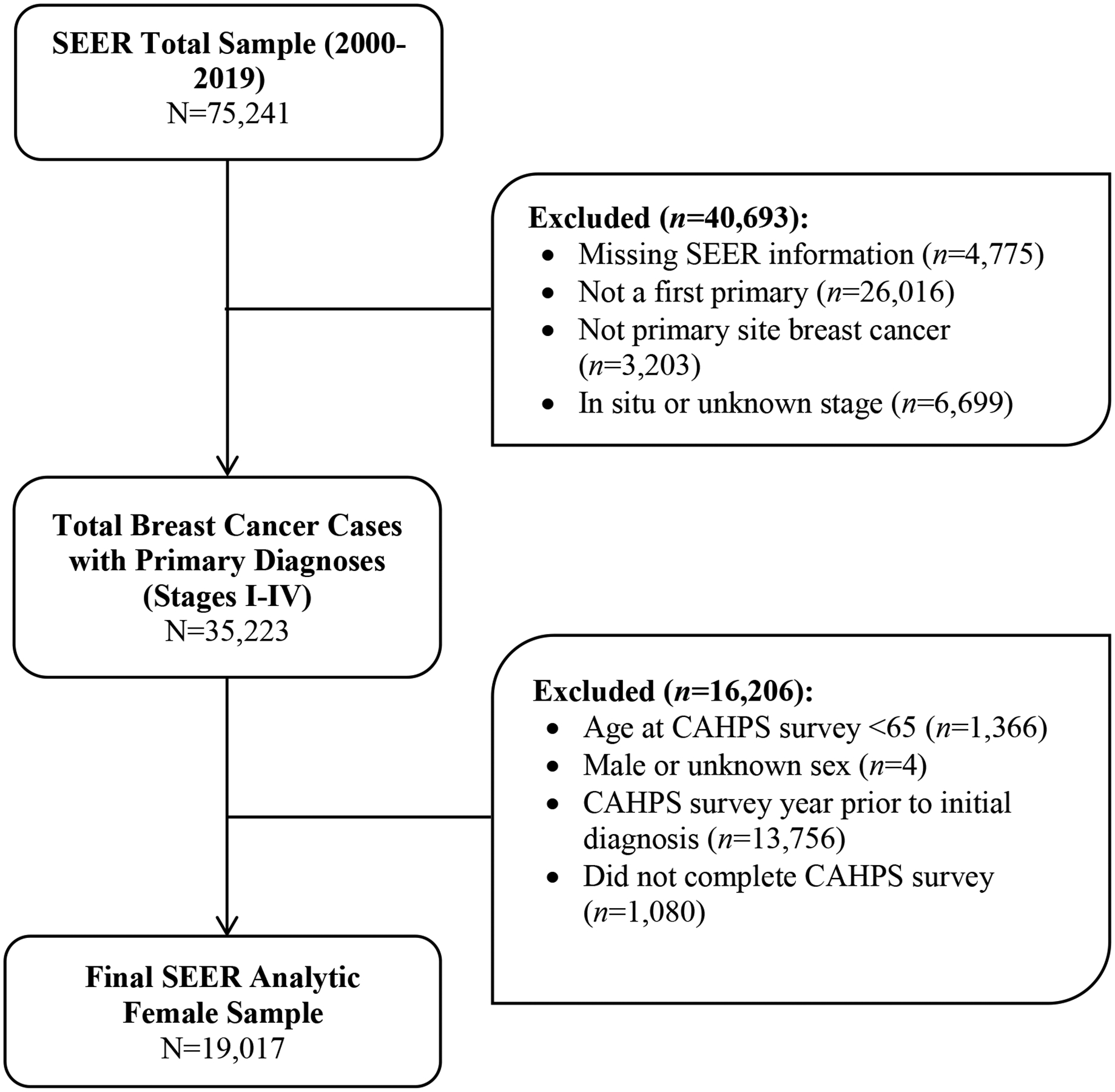

The SEER-CAHPS data linkage combined NCI’s SEER cancer diagnostic, treatment, and mortality data and CMS’ CAHPS self-reported survey outlining the experienced quality of health and provider care. The SEER program is an epidemiologic surveillance system comprised population-based tumor registries across the United States to determine cancer incidence and survival [18]. Individuals who have received a cancer diagnosis in the following areas are reflected in a SEER registry in various years: Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Jose California, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Georgia, Iowa, New Mexico, Seattle, Utah, Idaho, Louisiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York. This linkage has been previously described in detail elsewhere [18, 19]. There were 75,241 distinct SEER breast cancer cases which data were available in the specified time range (2000–2019). A final analytic sample of 19,017 was determined based on the following eligibility criteria: completed a CAHPS survey between 2000 and 2019, diagnosed with first primary invasive breast cancer (stages I-IV) in SEER regions, were female, aged ≥ 65 at CAHPS survey, and completed their CAHPS survey after initial diagnosis. Cases were excluded if they did not have a first primary or primary site of breast cancer, diagnosed with in situ or unknown breast cancer, were aged < 65 at CAHPS survey, did not report a race or ethnicity, reported male or unknown sex, completed a CAHPS survey prior to initial cancer diagnosis, and/or did not complete a CAHPS survey. See Supplement A for a diagram of exclusionary processes. For analytic purposes, the first CAHPS survey post-diagnosis of primary invasive breast cancer was used for CAHPS-related variables. CAHPS survey overall ratings are designed to capture patient ratings of specific aspects of care, while composite scores are calculated domain-specific experiences of care [20]. Composite scores are calculated by CMS to reflect a zero to 100 scale, with each domain item given equal weight. Details concerning SEER-CAHPS sample selection, recruitment, administration, response rates, and analytic adjustments have been previously published [18, 21, 22].

Model variables

Exposure

Several clinical cancer characteristics were included as exposure variables in the current study: extent of disease, estrogen receptor (ER) status, receipt of chemotherapy as well as any type of radiation treatment(s). Extent of disease was a three-level variable (localized [referent], regional, distant). ER status was originally coded as positive, negative, borderline, unknown, missing but was condensed as follows: (ER + [referent], ER−, unknown/missing); borderline cases were dropped. Receipt of chemotherapy was analyzed as follows: no/unknown [referent], chemotherapy, missing. Receipt of radiation was originally categorized as none, beam, radioactive implants, radioisotopes, combination, radiation not otherwise specified, other, patient refused, recommended but unknown if completed) but was condensed (no radiation/unknown [referent], radiation, missing). Exposure variables were also included as covariates for multivariable models.

Outcomes

Quality of care outcomes were estimated utilizing several CAHPS composite variables (Getting Care Quickly, Getting Needed Care, Physician Communication, Getting Needed Prescription Drug[s]) and item-level ratings (Overall Care Rating, Health Plan Rating, Physician Rating). Composite scores were scored from zero (worst possible) to 100 (best possible). Single-item global rating outcomes originally ranged from zero (worst possible) to 10 (best possible) but were transformed using linear-mean scoring as recommended by NCI [20] and past literature [23] to reflect ratings ranging from zero (worst possible) to 100 (best possible).

Case-mix adjustments and covariates

Per SEER-CAHPS analytic guidance, the year 2000 case-mix adjustments (utilizing the first year of the pooled dataset, using common covariates across 2000–2019) were applied to control for variability in healthcare experience responses based on beneficiary characteristics [24]. Based on these guidelines [24], the following variables were adjusted for across analyses: age at CAHPS survey (65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, ≥ 85), education (< high school, high school/GED/some college, college graduate), general health status (excellent/very good, good, fair/poor), received help responding to survey (no, yes), and having a proxy answering questions on survey (no, yes). These case-mix adjustments originated from CAHPS survey data, where age at CAHPS survey, education, and general health status were recoded due to limited subgroup sample sizes.

Additional variables were also adjusted for across models in addition to the above case-mix adjustments. Age at primary breast cancer diagnosis, years from diagnosis to CAHPS survey, year of CAHPS survey, and number of comorbid conditions were modeled as continuous covariates. Years from diagnosis to CAHPS survey was calculated from date of CAHPS survey and date of primary breast cancer diagnosis while number of comorbid conditions originated from the CAHPS comorbidity data file and was determined by CMS’ multimorbidity guidelines [25]. Mental health status was originally comprised five categories (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor) but for the current study, was collapsed to three categories (excellent/very good, good, fair/poor) to increase subsample group size.

Stratifications

The following variables were utilized as stratifications in separate models: race/ethnicity, census tract poverty indicator, education (as categorized above), and Medicare plan. Race/ethnicity was originally two separate variables in the SEER data file, and each were coded as follows: self-reported race (white, Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, unknown); self-reported Hispanic origin (not Hispanic/Latina, Hispanic/Latina). These variables were condensed into one race/ethnicity variable (non-Hispanic white [NHW, referent], non-Hispanic Black [NHB], non-Hispanic Asian [NHA including Pacific Islander], Hispanic, other/multi-racial [including American Indian/Alaska Native, multi-racial, unknown]). Area-level poverty was analyzed using the SEER census tract poverty indicator (0– < 5%, 5– < 10%, 10– < 20%, 20–100% poverty) but was dichotomized for the purposes of analysis (0– < 20% [referent], 20–100% poverty). Education was originally multinomial but was categorized as described above. Medicare plan was also dichotomized (other [includes prescription drug plan [PDP] and MA, referent], FFS) from its original form (PDP, MA, FFS) [21]. When not being currently modeled as a stratification, variables were included as covariates across subsequent models. Due to limited sample size, other/multi-racial subgroups were excluded from stratified analyses.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted utilizing Stata statistical software, version 16[26]. Descriptive univariate Chi-square tests for categorical variables and analyses of variance for continuous variables were examined. Models depicting unstandardized betas (β) and standard error estimates were analyzed utilizing multivariable linear regression models to determine the relationships between several clinical cancer characteristics (extent of disease, ER status, receipt of chemotherapy and/or radiation, ER/PR status) and survivorship care patient experience outcomes while adjusting for SEER-CAHPS 2000 case-mix adjustments[24] and additional covariates (year of CAHPS survey, age at diagnosis, mental health status, years from diagnosis to CAHPS survey). Models included missing categories if missingness was ≥ 10%. For variables that did not have ≥ 10% missing, those observations were dropped from those models and noted in the footnotes of their respective table. Additionally, the current study maintained no/unknown category options for SEER-preferred variables, as depicted above. Statistical interactions were modeled by creating an interaction term between each clinical cancer characteristic variable and stratification variable. All statistical tests were two-sided, with main effects and statistical interactions interpreted as statistically significant indicated by p-values < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the study sample

Table 1 describes the sociodemographic and clinical cancer characteristics of the study population (N = 19,017). Most women were 75–79 years of age (n = 4,973, 26.2%), NHW (n = 14,859, 78.2%), had a high school diploma or GED (n = 6,158, 32.4%), and were not living in areas of poverty (n = 15,126, 79.5%). Clinically, the majority reported either PDP or MA plans (n = 14,466, 76.1%), ER + (n = 10,816, 56.9%), and were diagnosed with localized disease (n = 15,304, 80.5%). Only 19.0% were treated with chemotherapy (n = 3,614) and 40.5% with radiation (n = 7,701). The mean age at diagnosis was 69.2 years (SD = 8.45) and the average number of chronic conditions was a little less than 5 (SD = 3.51).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics – NCI & CMS’ SEER-CAHPS data linkage, years 1999–2019, female breast cancer survivors completing a CAHPS survey post-diagnosis (N = 19,017)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age at CAHPS survey ☐ | |

| 65 – 69 | 4296 (22.6) |

| 70 – 74 | 4973 (26.2) |

| 75 – 79 | 4090 (21.5) |

| 80 – 84 | 3056 (16.1) |

| ≥ 85 | 2602 (13.7) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) |

| Age at diagnosis ☐ | |

| ≤ 69 years at diagnosis | 10,212 (53.7) |

| ≥70 years at diagnosis | 8805 (46.3) |

| Missing/Unknown | 0 (0.0) |

| Census tract poverty indicator | |

| 0%→ 20% poverty | 15,126 (79.5) |

| 20%—100% poverty | 2649 (13.9) |

| Missing/Unknown | 1242 (6.5) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| ;Non-Hispanic white (NHW) | 14,859 (78.2) |

| ;Non-Hispanic Black (NHB) | 1544 (8.1) |

| ;Non-Hispanic Asian (NHA) | 1239 (6.5) |

| Hispanic | 1181 (6.2) |

| Other/Multi-racial | 194 (1.0) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) |

| Educational ☐ | |

| < High school | 2673 (14.1) |

| High school graduate or GED | 6158 (32.4) |

| Some college | 4822 (25.4) |

| College graduate or higher | 4217 (22.2) |

| Missing/Unknown | 1147 (6.0) |

| Medicare plan type | |

| FFS Medicare | 4551 (23.9) |

| Other** | 14,466 (76.1) |

| Missing/Unknown | 0 (0.0) |

| ER status | |

| ER + | 10,816 (56.9) |

| ER− | 1921 (10.1) |

| Borderline | 13 (0.1) |

| Unknown or Not 1990 + | 1330 (7.0) |

| Missing | 4937 (25.9) |

| Extent of disease | |

| Localized | 15,304 (80.5) |

| Regional | 3304 (17.4) |

| Distant | 409 (2.1) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) |

| Chemotherapy for treatment | |

| No/Unknown | 10,466 (55.0) |

| Chemotherapy | 3614 (19.0) |

| Missing | 4937 (26.0) |

| Radiation for treatment | |

| No/Unknown/Other≠ | 6379 (33.5) |

| Radiation£ | 7701 (40.5) |

| Missing | 4937 (26.0) |

| M (SD) [Range] | |

| Age at diagnosis (continuous) ☐ | 69.2 (8.45) [33 – 100] |

| Years from diagnosis to CAHPS survey | 6.10 (4.92) [0 – 42.2] |

| Number of CMS comorbid conditions *** | 4.65 (3.51) [1 – 16] |

| Getting care quickly (composite) | 72.7 (23.6) [0 – 100] |

| Getting needed care (composite) | 86.8 (20.2) [0 – 100] |

| Physician communication (composite) | 90.3 (15.9) [0 – 100] |

| Getting needed prescription drug(s) (composite) | 91.1 (18.3) [0 – 100] |

| Overall care rating | 87.5 (16.6) [0 – 100] |

| Health plan rating | 86.2 (17.2) [0 – 100] |

| Personal doctor rating | 90.8 (14.5) [0 – 100] |

CMS Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

ER estrogen receptor

FFS Fee-for-service

NCI National Cancer Institute

NHA non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander

NHB non-Hispanic Black/African American

NHW non-Hispanic white

PR progesterone status

SEER Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program

Includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Other unspecified, unknown, or multi-racial

Includes Prescription Drug Plan (PDP), Medicare Advantage (MA), and MA combinations (MA-PDP, MA-Preferred Provider Organization [PPO])

CMS comorbid conditions included those listed: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Chronic-Conditions/CC_Main

Indicates a variable that is mutually adjusted as a case-mix or covariate adjustment when not being included as a stratification

Includes no radiation, unknown/missing, and patients who were recommended radiation (but unknown if they completed) or patients who refused radiation

Includes all types of radiation (beam radiation, radioactive implants, radioisotopes, combination radiation, radiation not otherwise specified, and other types of radiation)

Bold font indicates significant p-value of one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables or Chi-square analyses for categorical variables

Overall associations

Table 2 depicts the relationship between clinical breast cancer characteristics, treatments, and CAHPS quality of care outcomes. Survivors with regional breast cancer at diagnosis reported higher mean scores for Getting Needed Care (β = 1.00, SE = 0.46, p = 0.03) compared to those with localized disease at diagnosis. Findings were similar among survivors who had undergone chemotherapy for treatment, where Getting Needed Care average scores were higher (β = 1.05, SE = 0.48, p = 0.03) compared to those who exhibited no/unknown chemotherapy use. Additionally, women who were treated with chemotherapy reported higher mean scores on Overall Care ratings (β = 0.87, SE = 0.38, p = 0.02) in contrast to those with no/unknown chemotherapy use. Women diagnosed with distant breast cancer reported lower mean scores for Physician Communication (β = − 1.94, SE = 0.92, p = 0.03) compared to those with localized disease. There were no significant associations for the following outcomes: Getting Care Quickly, Getting Needed Prescription Drug(s), Health Plan rating, or Physician Rating.

Table 2.

Adjusted beta and unstandardized standard error from linear regression analyses of composite measures and single-item ratings associated with clinical cancer characteristics among female breast cancer survivors in SEER-CAHPS completing a CAHPS survey post-diagnosis 2000–2019 (N = 19,017)

| Getting care quickly | Getting needed care | Physician communication | Getting needed prescription drugs | Overall care rating | Health plan rating | Physician rating | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | |

| No. included in regression | 16,043 | 14,628 | 14,461 | 13,287 | 16,117 | 16,603 | 14,500 | |||||||

| Extent of disease: localized (ref) | ||||||||||||||

| Regional | 0.37 (0.52) | 0.47 | 1.00 (0.46) | 0.03 | 0.30 (0.37) | 0.41 | 0.21 (0.45) | 0.62 | 0.70 (0.36) | 0.05 | 0.29 (0.37) | 0.43 | 0.50 (0.34) | 0.13 |

| Distant | − 0.52 (1.31) | 0.69 | 0.17 (1.14) | 0.88 | − 1.94 (0.92) | 0.03 | − 1.50 (1.07) | 0.16 | − 1.37 (0.90) | 0.12 | − 0.03 (0.93) | 0.97 | − 1.57 (0.86) | 0.06 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | ||||||||||||||

| ER− | − 0.09 (0.65) | 0.88 | 0.46 (0.57) | 0.41 | 0.13 (0.46) | 0.77 | − 0.34 (0.55) | 0.53 | − 0.22 (0.44) | 0.61 | − 0.16 (0.46) | 0.73 | − 0.28 (0.42) | 0.49 |

| Missing/unknown | − 0.38 (0.65) | 0.56 | 0.22 (0.58) | 0.70 | − 0.77 (0.46) | 0.09 | 0.44 (0.55) | 0.41 | − 0.56 (0.45) | 0.22 | 0.16 (0.46) | 0.72 | − 0.33 (0.42) | 0.42 |

| Chemotherapy: no chemotherapy/unknown (ref) | ||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 0.44 (0.55) | 0.42 | 1.05 (0.48) | 0.03 | 0.45 (0.39) | 0.24 | 0.30 (0.47) | 0.51 | 0.87 (0.38) | 0.02 | 0.39 (0.39) | 0.32 | − 0.08 (0.35) | 0.80 |

| Missing | 0.41 (1.04) | 0.69 | − 1.28 (0.92) | 0.16 | 0.88 (0.73) | 0.22 | 0.29 (0.88) | 0.74 | − 0.26 (0.72) | 0.71 | 0.13 (0.74) | 0.85 | 0.57 (0.67) | 0.39 |

| Radiation: no radiation/unknown (ref) | ||||||||||||||

| Radiation | − 0.01 (0.43) | 0.97 | 0.59 (0.38) | 0.12 | 0.20 (0.30) | 0.51 | 0.28 (0.37) | 0.44 | 0.38 (0.30) | 0.20 | 0.03 (0.31) | 0.91 | 0.11 (0.28) | 0.69 |

| Missing | − 0.50 (1.24) | 0.68 | − 2.21 (1.10) | 0.04 | 0.37 (0.87) | 0.67 | 0.25 (1.05) | 0.81 | − 1.25 (0.86) | 0.14 | − 0.57 (0.89) | 0.51 | 0.97 (0.80) | 0.22 |

CAHPS Consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems, NHA non-hispanic asian or pacific islander, NHB non-hispanic black or African American, NHW non-Hispanic white, SE standard error, SEER Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program

Includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Other unspecified, unknown, or multi-racial

Missing values: Getting care quickly composite (2963); Getting needed care composite (4379); Physician communication composite (4548); Getting needed prescription drugs composite (5722); Overall care rating (2890); Health plan rating (2402); Physician rating (4,509)

Case-mix adjustments for years 1999–2019: Age at CAHPS survey (65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, ≥ 85); Education (< high school, high school graduate/GED/some college, college graduate); General health status (excellent/very good, good, fair/poor); Received help responding (no, yes); Proxy answered questions for respondent (no, yes)

Additional adjusted covariates: age at diagnosis (continuous); Mental health status (excellent/very good; good; fair/poor; missing); years from diagnosis to CAHPS survey (continuous); Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) multimorbidity (continuous); CAHPS survey year (continuous); Medicare plan type (other [prescription drug plan {PDP} or Medicare Advantage {MA}], fee-for-service Medicare); area-level poverty (0– < 20% poverty; 20–100% poverty; unknown/missing); race/ethnicity (NHW, NHB, NHA, Hispanic)

Borderline cases for ER status (13) were excluded

Predictors are mutually adjusted

Bold font indicates statistically significant with corresponding p < .05

Stratifications and interactions by race/ethnicity

Table 3 depicts the relationships between breast cancer tumor factors (extent of disease, ER status) and CAHPS quality of care outcomes stratified by race/ethnicity. NHB survivors who had regional breast cancer at diagnosis reported significantly higher ratings for Overall Care (β = 3.13, SE = 1.47, p = 0.03) compared to NHB survivors with localized disease, however this association was not significant among NHW survivors (p-interaction = 0.04). Similar findings were found for the outcome of Physician Rating, where NHB women with regional disease also had significantly higher scores (β = 3.47, SE = 1.19, p = 0.004) compared to NHB women with localized breast cancer. This relationship was not significant among NHW survivors (p-interaction = 0.02).

Table 3.

Multivariable adjusted linear regression for composite measures and single-rating items associated with breast cancer tumor characteristics among female breast cancer survivors in SEER-CAHPS 2000–2019 completing a CAHPS survey post-diagnosis stratified by race/ethnicity

| OUTCOMES PREDICTOR | Stratification: race/ethnicity | p-int. (predictor x NHB) | p-int. (predictor x NHA) | p-int. (predictor x Hispanic) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHW (N = 12,528) | NHB (N = 1332) | NHA (N = 1020) | Hispanic (N = 1001) | ||||||||||||

| N | β (SE) | p | N | β (SE) | p | N | β (SE) | p | N | β (SE) | p | ||||

| Getting care quickly (N = 15,881) | |||||||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Regional | 2090 | 0.35 (0.58) | 0.54 | 245 | 0.34 (2.05) | 0.86 | 208 | − 1.98 (2.09) | 0.34 | 223 | 2.37 (2.14) | 0.26 | 0.78 | 0.66 | 0.32 |

| Distant | 264 | − 0.61 (1.42) | 0.66 | 34 | 1.53 (4.88) | 0.75 | 14 | 1.51 (6.97) | 0.82 | 18 | − 6.14 (6.27) | 0.32 | 0.96 | 0.71 | 0.27 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| ER− | 1096 | − 0.06 (0.74) | 0.93 | 234 | − 0.01 (2.20) | 0.99 | 151 | − 0.23 (2.33) | 0.94 | 123 | 1.58 (2.61) | 0.61 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.32 |

| Missing/Unknown | 4284 | 0.12 (0.72) | 0.85 | 417 | − 0.54 (2.57) | 0.83 | 128 | − 7.77 (2.90) | 0.007 | 273 | − 2.42 (2.76) | 0.38 | 0.95 | 0.70 | 0.27 |

| Getting needed care (N = 14,472) | |||||||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Regional | 1950 | 1.12 (0.50) | 0.02 | 215 | 2.82 (1.88) | 0.13 | 189 | − 1.58 (1.98) | 0.42 | 202 | − 0.76 (2.00) | 0.70 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.67 |

| Distant | 254 | 1.44 (1.22) | 0.23 | 30 | − 4.43 (4.47) | 0.32 | 12 | − 8.54 (6.71) | 0.20 | 18 | − 6.05 (5.66) | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.26 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| ER− | 1021 | 0.41 (0.65) | 0.52 | 199 | 4.12 (2.03) | 0.04 | 137 | − 1.76 (2.19) | 0.42 | 107 | − 1.77 (2.49) | 0.47 | 0.33 | 0.24 | 0.68 |

| Missing/Unknown | 3907 | 0.67 (0.63) | 0.28 | 354 | − 0.11 (2.36) | 0.96 | 116 | − 3.28 (2.72) | 0.22 | 235 | − 2.95 (2.66) | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.25 |

| Physician communication (N = 14,314) | |||||||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Regional | 1824 | 0.19 (0.42) | 0.64 | 231 | 1.38 (1.29) | 0.28 | 193 | − 0.88 (1.43) | 0.53 | 217 | 0.17 (1.36) | 0.89 | 0.38 | 0.64 | 0.60 |

| Distant | 240 | − 1.78 (1.02) | 0.08 | 27 | − 0.99 (3.34) | 0.76 | 12 | − 1.78 (4.93) | 0.71 | 19 | − 3.19 (3.83) | 0.40 | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.91 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| ER− | 970 | 0.10 (0.54) | 0.85 | 218 | − 0.18 (1.40) | 0.89 | 143 | 0.31 (1.57) | 0.84 | 111 | 0.68 (1.72) | 0.69 | 0.40 | 0.63 | 0.62 |

| Missing/Unknown | 3941 | − 0.57 (0.52) | 0.27 | 390 | − 1.95 (1.64) | 0.23 | 116 | − 2.10 (2.00) | 0.29 | 248 | − 1.76 (1.75) | 0.31 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.92 |

| Getting needed prescription drugs (N = 13,137) | |||||||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Regional | 1651 | 0.15 (0.50) | 0.75 | 219 | 1.16 (1.59) | 0.46 | 179 | − 0.39 (1.70) | 0.81 | 199 | 1.22 (1.84) | 0.50 | 0.21 | 0.91 | 0.27 |

| Distant | 228 | − 0.62 (1.18) | 0.59 | 33 | − 2.83 (3.63) | 0.43 | 15 | − 5.51 (5.03) | 0.27 | 18 | − 1.46 (5.15) | 0.77 | 0.54 | 0.31 | 0.87 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| ER− | 879 | − 0.49 (0.64) | 0.43 | 193 | 0.33 (1.77) | 0.84 | 139 | − 0.86 (1.83) | 0.63 | 108 | 0.03 (2.29) | 0.98 | 0.24 | 0.85 | 0.82 |

| Missing/Unknown | 3702 | 1.24 (0.62) | 0.04 | 378 | − 1.97 (2.01) | 0.32 | 120 | − 2.00 (2.24) | 0.37 | 265 | − 2.75 (2.32) | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.63 | 0.05 |

| Overall care rating (N = 15,957) | |||||||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Regional | 2094 | 0.34 (0.39) | 0.38 | 248 | 3.13 (1.47) | 0.03 | 219 | − 1.18 (1.41) | 0.40 | 224 | 2.64 (1.56) | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.23 |

| Distant | 271 | − 1.26 (0.95) | 0.18 | 31 | − 0.60 (3.70) | 0.87 | 14 | − 0.27 (4.80) | 0.95 | 19 | − 7.01 (4.48) | 0.11 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.10 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| ER− | 1105 | 0.02 (0.50) | 0.95 | 228 | − 2.05 (1.60) | 0.20 | 157 | − 0.01 (1.58) | 0.99 | 125 | 2.10 (1.90) | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.24 |

| Missing/Unknown | 4307 | − 0.42 (0.49) | 0.39 | 413 | − 0.05 (1.89) | 0.97 | 126 | − 4.58 (1.98) | 0.02 | 277 | − 1.39 (2.03) | 0.49 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.10 |

| Health plan rating (N = 16,432) | |||||||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Regional | 2166 | 0.40 (0.42) | 0.34 | 259 | 2.29 (1.34) | 0.08 | 226 | 0.06 (1.38) | 0.96 | 232 | − 2.40 (1.39) | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.10 |

| Distant | 275 | 0.47 (1.04) | 0.64 | 33 | − 0.26 (3.30) | 0.93 | 15 | − 3.02 (4.60) | 0.51 | 21 | − 1.26 (3.94) | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.30 | 0.83 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| ER− | 1134 | − 0.35 (0.55) | 0.52 | 241 | − 1.13 (1.45) | 0.43 | 157 | 0.87 (1.56) | 0.57 | 129 | 1.37 (1.72) | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.11 |

| Missing/Unknown | 4433 | 0.50 (0.53) | 0.34 | 421 | − 0.98 (1.70) | 0.56 | 131 | − 4.31 (1.90) | 0.02 | 290 | 0.02 (1.78) | 0.98 | 0.73 | 0.30 | 0.83 |

| Physician rating (N = 14,354) | |||||||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Regional | 1837 | 0.38 (0.38) | 0.31 | 232 | 3.47 (1.19) | 0.004 | 191 | − 0.91 (1.24) | 0.46 | 212 | − 0.61 (1.39) | 0.65 | 0.02 | 0.41 | 0.19 |

| Distant | 236 | − 2.13 (0.93) | 0.02 | 24 | 0.57 (3.27) | 0.86 | 12 | 3.01 (4.24) | 0.47 | 18 | − 0.35 (3.99) | 0.92 | 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.58 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| ER− | 977 | − 0.41 (0.49) | 0.40 | 219 | 0.14 (1.30) | 0.91 | 141 | − 0.29 (1.36) | 0.83 | 109 | 0.38 (1.76) | 0.82 | 0.67 | 0.92 | 0.91 |

| Missing/Unknown | 3956 | − 0.33 (0.47) | 0.47 | 379 | 1.24 (1.53) | 0.41 | 115 | − 3.12 (1.72) | 0.07 | 246 | − 1.90 (1.78) | 0.28 | 0.19 | 0.002 | 0.17 |

CAHPS Consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems, ER estrogen receptor, int. interaction, NHA non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, NHB non-Hispanic Black or African American, NHW non-Hispanic white, SE standard error, SEER Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program

Missing values: Getting care quickly composite (2963); Getting needed care composite (4379); Physician communication composite (4548); Getting needed prescription drugs composite (5722); Overall care rating (2890); Health plan rating (2402); Physician rating (4509); race/ethnicity (194)

Case-mix adjustments for years 1999–2019: Age at CAHPS survey (65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, ≥ 85); Education (< high school, high school graduate/GED/some college, college graduate); General health status (excellent/very good, good, fair/poor); Received help responding (no, yes); Proxy answered questions for respondent (no, yes)

Additional adjusted covariates: age at diagnosis (continuous); Mental health status (excellent/very good; good; fair/poor; missing); years from diagnosis to CAHPS survey (continuous); Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) multimorbidity (continuous); CAHPS survey year (continuous); area-level poverty (0– < 20% poverty; 20–100% poverty; unknown/missing); Medicare plan type (other [prescription drug plan {PDP} or Medicare Advantage {MA}], fee-for-service Medicare)

Borderline cases for ER status (13) were excluded

Predictors and stratifications are mutually adjusted

Bold font indicates statistically significant with corresponding p < .05

Table 4 depicts the relationships between breast cancer treatments (chemotherapy, radiation) and CAHPS quality of care outcomes stratified by race/ethnicity. NHA survivors treated with chemotherapy reported significantly higher mean scores for Getting Care Quickly (β = 7.02, SE = 2.09, p = 0.001) compared to NHA survivors who had no/unknown chemotherapy use, while this association among NHW survivors was not significant (p-interaction = 0.02). NHA survivors treated with radiation therapy reported significantly higher scores for Getting Needed Care (β = 4.14, SE = 1.60, p = 0.01) compared to NHA survivors using no/unknown radiation, while the association among NHW survivors was not significant (p-interaction = 0.003).

Table 4.

Multivariable adjusted linear regression for composite measures and single-rating items associated with breast cancer treatment among female breast cancer survivors in SEER-CAHPS 2000–2019 completing a CAHPS survey post-diagnosis stratified by race/ethnicity

| OUTCOMES PREDICTOR | Stratification: race/ethnicity | p-int. (predictor x NHB) | p-int. (predictor x NHA) | p-int. (predictor x Hispanic) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHW (N = 12,528) | NHB (N = 1332) | NHA (N = 1020) | Hispanic (N = 1001) | ||||||||||||

| N | β (SE) | p | N | β (SE) | p | N | β (SE) | p | N | β (SE) | p | ||||

| Getting care quickly (N = 15,881) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 2219 | 0.47 (0.61) | 0.44 | 333 | − 3.00 (2.02) | 0.13 | 268 | 7.02 (2.09) | 0.001 | 235 | − 1.18 (2.29) | 0.60 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.49 |

| Missing | 3416 | 0.58 (1.13) | 0.60 | 313 | − 6.82 (4.25) | 0.10 | 57 | − 0.34 (5.33) | 0.94 | 196 | 2.05 (4.58) | 0.65 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.71 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Radiation | 5104 | − 0.29 (0.48) | 0.54 | 518 | 2.69 (1.77) | 0.12 | 517 | − 0.49 (1.68) | 0.76 | 431 | − 0.74 (1.87) | 0.69 | 0.05 | 0.73 | 0.71 |

| Missing | 3416 | − 0.95 (1.38) | 0.49 | 313 | 4.56 (4.46) | 0.30 | 57 | − 15.3 (5.67) | 0.007 | 196 | 2.95 (5.40) | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.07 | 0.74 |

| Getting needed care (N = 14,472) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 2079 | 1.10 (0.53) | 0.04 | 289 | − 0.70 (1.85) | 0.70 | 239 | 4.12 (2.00) | 0.04 | 216 | − 0.15 (2.14) | 0.94 | 0.36 | 0.40 | 0.25 |

| Missing | 3100 | − 0.81 (0.99) | 0.41 | 263 | − 8.52 (3.86) | 0.02 | 52 | − 10.4 (5.01) | 0.03 | 171 | 8.64 (4.35) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.40 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Radiation | 4728 | 0.28 (0.42) | 0.49 | 469 | 2.50 (1.62) | 0.12 | 443 | 4.14 (1.60) | 0.01 | 386 | − 2.71 (1.75) | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.003 | 0.07 |

| Missing | 3100 | − 2.44 (1.20) | 0.04 | 263 | − 2.10 (4.15) | 0.61 | 52 | − 10.3 (5.38) | 0.05 | 171 | 3.53 (5.16) | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.21 |

| Physician communication (N = 14,314) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 1942 | 0.36 (0.45) | 0.42 | 307 | 0.12 (1.28) | 0.92 | 245 | 1.73 (1.44) | 0.23 | 221 | − 0.20 (1.50) | 0.89 | 0.99 | 0.73 | 0.66 |

| Missing | 3136 | 1.29 (0.82) | 0.11 | 294 | − 2.02 (2.71) | 0.45 | 50 | − 5.62 (3.67) | 0.12 | 173 | 3.54 (2.95) | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.49 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Radiation | 4466 | 0.03 (0.35) | 0.91 | 490 | 1.87 (1.12) | 0.09 | 486 | 1.04 (1.15) | 0.36 | 398 | − 1.08 (1.21) | 0.37 | 0.08 | 0.45 | 0.25 |

| Missing | 3136 | 0.65 (1.00) | 0.51 | 294 | 1.48 (2.83) | 0.60 | 50 | − 6.99 (3.97) | 0.07 | 173 | 1.78 (3.55) | 0.61 | 0.87 | 0.04 | 0.31 |

| Getting needed prescription drugs (N = 13,137) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 1761 | − 0.53 (0.53) | 0.31 | 294 | 2.24 (1.58) | 0.15 | 222 | 2.61 (1.70) | 0.12 | 225 | 1.56 (1.95) | 0.42 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.34 |

| Missing | 2996 | 0.29 (0.97) | 0.76 | 282 | 1.16 (3.33) | 0.72 | 56 | − 2.81 (4.15) | 0.49 | 195 | 2.00 (3.96) | 0.61 | 0.36 | 0.61 | 0.35 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Radiation | 3984 | 0.27 (0.42) | 0.50 | 459 | − 0.13 (1.39) | 0.92 | 455 | 2.17 (1.35) | 0.10 | 383 | − 0.70 (1.62) | 0.66 | 0.97 | 0.08 | 0.33 |

| Missing | 2996 | 1.92 (1.19) | 0.10 | 282 | − 3.57 (3.48) | 0.30 | 56 | − 3.69 (4.52) | 0.41 | 195 | − 2.55 (4.61) | 0.58 | 0.19 | 0.80 | 0.12 |

| Overall care rating (N = 15,957) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 2240 | 1.23 (0.42) | 0.003 | 329 | − 1.85 (1.47) | 0.20 | 279 | 3.26 (1.41) | 0.02 | 240 | 0.01 (1.67) | 0.99 | 0.05 | 0.54 | 0.50 |

| Missing | 3457 | 0.29 (0.77) | 0.70 | 309 | − 1.92 (3.10) | 0.53 | 54 | − 4.56 (3.69) | 0.21 | 203 | − 3.28 (3.34) | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.10 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Radiation | 5065 | 0.06 (0.32) | 0.83 | 522 | 1.34 (1.28) | 0.29 | 534 | 2.00 (1.14) | 0.08 | 426 | 0.86 (1.35) | 0.52 | 0.28 | 0.06 | 0.62 |

| Missing | 3457 | − 2.03 (0.94) | 0.03 | 309 | 4.49 (3.26) | 0.16 | 54 | − 7.07 (3.91) | 0.07 | 203 | − 1.58 (3.94) | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.15 | 0.25 |

| Health plan rating (N = 16,432) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 2275 | 0.35 (0.45) | 0.43 | 333 | − 0.84 (1.35) | 0.53 | 279 | 0.87 (1.40) | 0.53 | 247 | 1.22 (1.50) | 0.41 | 0.60 | 0.81 | 0.94 |

| Missing | 3538 | 0.41 (0.83) | 0.61 | 309 | − 2.97 (2.80) | 0.28 | 53 | − 7.41 (3.64) | 0.04 | 206 | 2.41 (3.01) | 0.42 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.70 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Radiation | 5204 | 0.02 (0.35) | 0.93 | 529 | 0.62 (1.17) | 0.59 | 558 | 0.56 (1.12) | 0.61 | 459 | − 1.31 (1.22) | 0.28 | 0.60 | 0.51 | 0.27 |

| Missing | 3538 | − 0.24 (1.02) | 0.81 | 309 | − 0.05 (2.98) | 0.98 | 53 | − 8.02 (3.86) | 0.03 | 206 | − 2.65 (3.54) | 0.45 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.92 |

| Physician rating (N = 14,354) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 1946 | 0.35 (0.40) | 0.37 | 302 | − 2.28 (1.19) | 0.05 | 242 | 0.59 (1.25) | 0.63 | 223 | − 1.66 (1.51) | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.92 | 0.05 |

| Missing | 3143 | 1.26 (0.74) | 0.08 | 285 | − 3.94 (2.52) | 0.11 | 49 | − 5.50 (3.18) | 0.08 | 171 | − 0.39 (3.01) | 0.89 | 0.05 | < 0.001 | 0.33 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||||||

| Radiation | 4497 | − 0.06 (0.31) | 0.84 | 485 | 1.52 (1.05) | 0.14 | 488 | − 0.44 (0.99) | 0.65 | 401 | 1.07 (1.23) | 0.42 | 0.21 | 0.93 | 0.48 |

| Missing | 3143 | 0.42 (0.91) | 0.67 | 285 | 3.68 (2.63) | 0.16 | 49 | − 7.60 (3.45) | 0.02 | 171 | 5.09 (3.57) | 0.15 | 0.38 | < 0.001 | 0.88 |

CAHPS Consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems, int. interaction, NHA non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, NHB non-Hispanic Black or African American, NHW non-Hispanic white, ref = referent, SE standard error, SEER Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program

Missing values: Getting care quickly composite (2963); Getting needed care composite (4379); Physician communication composite (4548); Getting needed prescription drugs composite (5722); Overall care rating (2890); Health plan rating (2402); Physician rating (4509); race/ethnicity (194)

Case-mix adjustments for years 1999–2019: Age at CAHPS survey (65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, ≥ 85); Education (< high school, high school graduate/GED/some college, college graduate); General health status (excellent/very good, good, fair/poor); Received help responding (no, yes); Proxy answered questions for respondent (no, yes)

Additional adjusted covariates: age at diagnosis (continuous); Mental health status (excellent/very good; good; fair/poor; missing); years from diagnosis to CAHPS survey (continuous); Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) multimorbidity (continuous); CAHPS survey year (continuous); area-level poverty (0- < 20% poverty; 20–100% poverty; unknown/missing); Medicare plan type (other [prescription drug plan {PDP} or Medicare Advantage {MA}], fee-for-service Medicare)

Borderline cases for ER status (13) were excluded

Predictors and stratifications are mutually adjusted

Bold font indicates statistically significant with corresponding p < .05

Stratifications and interactions by education

Table 5 shows the associations between breast cancer tumor characteristics (extent of disease, ER status) and CAHPS quality of care outcomes stratified by education. Among survivors with less than a high school education, women with distant breast cancer at diagnosis reported significantly lower Physician Communication scores (β = − 7.24, SE = 2.48, p = 0.004) compared to women with localized disease; this association was not significant among women reporting a high school/GED/some college education (p-interaction = 0.01). Additionally, for the outcome of Physician Communication, the interaction between college educated women and women with less than high school education was statistically significant (p-interaction = 0.008); however, the result among college educated women with distant stage was not statistically significant. Findings among Overall Care Ratings mirrored those above, where those with less than a high school education with distant disease at diagnosis reported significantly lower scores (β = − 6.40, SE = 2.72, p = 0.01) compared to those with localized disease and the same educational attainment. However, the main effects for this association was not significant among survivors reporting a high school/GED/some college education (p-interaction = 0.01) or a college degree (p-interaction = 0.04). Physician Ratings also followed this trend, where those with less than a high school education and with distant breast cancer at diagnosis reported significantly lower scores (β = − 5.35, SE = 2.37, p = 0.02) compared to those the same education level and localized disease; the main effects for this association was not significant among those reporting a high school/GED/some college (p-interaction = 0.04) or a college degree (p-interaction = 0.04).

Table 5.

Multivariable adjusted linear regression for composite measures and single-item ratings associated with breast cancer tumor characteristics among female breast cancer survivors in SEER-CAHPS 2000–2019 completing a CAHPS survey post-diagnosis stratified by education

| OUTCOMES PREDICTOR | STRATIFICATION: Education | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < High School (N = 2673) | High School/GED/Some College (N = 10,980) | College Graduate (N = 4217) | p-int. (predictor x HS/GED/Some College) | p-int. (predictor x College Graduate) | |||||||

| N | β (SE) | p-value | N | β (SE) | p-value | N | β (SE) | p-value | |||

| Getting care quickly (N = 15,024) | |||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||

| Regional | 379 | − 0.71 (1.55) | 0.64 | 1596 | 1.20 (0.68) | 0.07 | 636 | − 0.93 (1.03) | 0.36 | 0.06 | 0.56 |

| Distant | 49 | − 6.42 (3.74) | 0.08 | 203 | 0.50 (1.67) | 0.76 | 16 | − 2.37 (2.84) | 0.40 | 0.05 | 0.31 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||

| ER− | 224 | 1.78 (1.90) | 0.34 | 966 | − 0.59 (0.83) | 0.47 | 331 | − 1.23 (1.33) | 0.35 | 0.40 | 0.33 |

| Missing/Unknown | 793 | 3.08 (1.87) | 0.09 | 2957 | − 1.00 (0.85) | 0.24 | 1086 | − 2.46 (1.32) | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Getting needed care (N = 13,787) | |||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||

| Regional | 339 | 0.69 (1.45) | 0.63 | 1467 | 1.10 (0.58) | 0.06 | 619 | 1.78 (0.94) | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.78 |

| Distant | 45 | − 3.90 (3.46) | 0.26 | 194 | 1.91 (1.40) | 0.17 | 62 | − 1.71 (2.54) | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.96 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||

| ER− | 204 | − 1.38 (1.77) | 0.43 | 874 | − 0.02 (0.71) | 0.97 | 318 | 1.51 (1.22) | 0.21 | 0.53 | 0.28 |

| Missing/Unknown | 692 | 1.12 (1.76) | 0.52 | 2686 | − 0.23 (0.73) | 0.74 | 1029 | 0.66 (1.21) | 0.58 | 0.25 | 0.83 |

| Physician communication (N = 13,589) | |||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||

| Regional | 364 | − 0.07 (1.05) | 0.94 | 1426 | 0.71 (0.47) | 0.13 | 544 | − 0.02 (0.79) | 0.97 | 0.42 | 0.82 |

| Distant | 49 | − 7.24 (2.48) | 0.004 | 180 | − 1.35 (1.17) | 0.24 | 53 | 0.79 (2.18) | 0.71 | 0.01 | 0.008 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||

| ER− | 220 | 0.71 (1.28) | 0.57 | 875 | − 0.24 (0.58) | 0.67 | 286 | − 0.33 (1.02) | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.71 |

| Missing/Unknown | 758 | − 2.31 (1.26) | 0.06 | 2752 | − 0.71 (0.59) | 0.22 | 952 | − 0.77 (1.01) | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.05 |

| Getting needed prescription drugs (N = 12,614) | |||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||

| Regional | 336 | − 0.15 (1.40) | 0.91 | 1338 | 0.90 (0.54) | 0.09 | 467 | − 0.39 (0.96) | 0.68 | 0.38 | 0.92 |

| Distant | 45 | − 1.36 (3.36) | 0.68 | 186 | − 0.76 (1.28) | 0.55 | 52 | − 3.63 (2.44) | 0.13 | 0.85 | 0.52 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||

| ER− | 204 | − 0.13 (1.72) | 0.93 | 822 | − 0.23 (0.66) | 0.72 | 245 | − 1.32 (1.21) | 0.27 | 0.91 | 0.57 |

| Missing | 770 | 1.70 (1.64) | 0.30 | 2634 | 0.41 (0.68) | 0.54 | 888 | − 0.18 (1.21) | 0.87 | 0.98 | 0.50 |

| Overall care rating (N = 15,174) | |||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||

| Regional | 373 | 1.36 (1.15) | 0.23 | 1629 | 0.14 (0.46) | 0.75 | 644 | 0.94 (0.64) | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.45 |

| Distant | 51 | − 6.40 (2.72) | 0.01 | 208 | − 0.10 (1.13) | 0.92 | 62 | 0.01 (1.77) | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||

| ER− | 231 | − 1.27 (1.39) | 0.36 | 987 | − 0.72 (0.56) | 0.20 | 332 | 0.47 (0.83) | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.22 |

| Missing/Unknown | 788 | − 1.13 (1.41) | 0.42 | 2999 | − 0.41 (0.59) | 0.48 | 1083 | − 0.98 (0.83) | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.41 |

| Health plan rating (N = 15,682) | |||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||

| Regional | 406 | − 0.30 (1.08) | 0.77 | 1688 | 0.36 (0.47) | 0.45 | 647 | 0.89 (0.78) | 0.25 | 0.96 | 0.84 |

| Distant | 52 | − 0.48 (2.63) | 0.85 | 213 | − 0.14 (1.17) | 0.90 | 63 | 1.11 (2.14) | 0.60 | 0.93 | 0.79 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||

| ER− | 255 | − 0.89 (1.30) | 0.49 | 1008 | − 0.30 (0.60) | 0.60 | 332 | − 0.11 (1.01) | 0.91 | 0.69 | 0.91 |

| Missing | 852 | 0.31 (1.31) | 0.80 | 3084 | 0.39 (0.50) | 0.50 | 1100 | − 0.43 (1.00) | 0.66 | 0.36 | 0.82 |

| Physician Rating (N = 13,635) | |||||||||||

| Extent of disease: Localized (ref) | |||||||||||

| Regional | 364 | 0.54 (0.98) | 0.58 | 1436 | 0.63 (0.43) | 0.14 | 538 | 0.42 (0.69) | 0.53 | 0.77 | 0.72 |

| Distant | 47 | − 5.35 (2.37) | 0.02 | 177 | − 1.09 (1.09) | 0.31 | 52 | 0.2 (1.91) | 0.87 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| ER status: ER + (ref) | |||||||||||

| ER− | 223 | 0.79 (1.19) | 0.50 | 875 | − 0.69 (0.53) | 0.19 | 287 | − 0.06 (0.88) | 0.94 | 0.38 | 0.68 |

| Missing/Unknown | 752 | − 0.15 (1.19) | 0.89 | 2765 | − 0.59 (0.54) | 0.27 | 951 | − 0.29 (0.88) | 0.73 | 0.54 | 0.12 |

CAHPS Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, ER estrogen receptor, GED general education development, HS high school, int. interaction, NHA non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, NHB non-Hispanic Black or African American, NHW non-Hispanic white, ref referent, SE standard error, SEER Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program

Missing values: Getting care quickly composite (2963); Getting needed care composite (4379); Physician communication composite (4548); Getting needed prescription drugs composite (5722); Overall care rating (2890); Health plan rating (2402); Physician rating (4509); other unspecified/unknown/multi-racial (194); education (1147)

Case-mix adjustments for years 1999–2019: Age at CAHPS survey (continuous); General health status (excellent/very good, good, fair/poor); Received help responding (no, yes); Proxy answered questions for respondent (no, yes)

Additional adjusted covariates: Age at diagnosis (65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, ≥ 85); Mental health status (excellent/very good; good; fair/poor; missing); years from diagnosis to CAHPS survey (continuous); Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) multimorbidity (continuous); CAHPS survey year (continuous); Medicare plan type (other [prescription drug plan {PDP} or Medicare Advantage {MA}], fee-for-service Medicare); area-level poverty (0- < 20% poverty; 20–100% poverty; unknown/missing); race/ethnicity (NHW, NHB, NHA, Hispanic), extent of disease (localized; regional; distant), chemotherapy (no/unknown; chemotherapy; missing), radiation (no/unknown; radiation; missing)

Borderline cases for ER status (13) were excluded

Predictors and stratifications are mutually adjusted

Bold font indicates statistically significant with corresponding p < .05

Table 6 depicts the relationships between breast cancer treatments (chemotherapy, radiation) and CAHPS quality of care outcomes stratified education. Among women with less than a high school education, survivors treated with chemotherapy reported significantly lower scores for Getting Care Quickly (β = − 3.85, SE = 1.72, p = 0.02) compared to survivors who exhibited no/unknown chemotherapy treatment, but main effect for this association was not significant among survivors with high school/GED/some college (p-interaction = 0.005). The opposite was observed among college graduate survivors who were treated with chemotherapy, as they reported significantly higher scores (β = 3.09, SE = 1.06, p = 0.004) compared to survivors with the same education who reported no/unknown chemotherapy use (p-interaction = 0.004). Coefficients for Physician Ratings comparing survivors who reported “yes” versus “no/unknown” for chemotherapy were not significant among any level of education, however, there were significant interactions between women reporting less than a high school education and women with a high school/GED/some college education (p-interaction = 0.02) and women with a less than high school education and college graduates (p = 0.03). Generally, those who received chemotherapy reported lower mean Physician Rating scores compared to those who had no/unknown chemotherapy use among survivors reporting less than a high school education, while those who received chemotherapy reported higher mean score among survivors with a high school/GED/some college and college degree.

Table 6.

Multivariable adjusted linear regression for composite measures and single-item ratings associated with breast cancer treatment among female breast cancer survivors in SEER-CAHPS 2000–2019 completing a CAHPS survey post-diagnosis stratified by education

| OUTCOMES PREDICTOR | Stratification: Education | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < High School (N = 2673) | High School/GED/Some College (N = 10,980) | College Graduate (N = 4217) | p-int. (predictor x HS/GED/Some College) | p-int. (predictor x College Graduate) | |||||||

| N | β (SE) | p-value | N | β (SE) | p-value | N | β (SE) | p-value | |||

| Getting Care Quickly (N = 15,024) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 348 | − 3.85 (1.72) | 0.02 | 1806 | 0.35 (0.71) | 0.61 | 764 | 3.09 (1.06) | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| Missing | 605 | 1.46 (3.01) | 0.62 | 2322 | 0.40 (1.36) | 0.76 | 857 | 0.55 (2.09) | 0.79 | 0.16 | 0.26 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Radiation | 752 | − 0.45 (1.31) | 0.72 | 3867 | 0.26 (0.57) | 0.63 | 1619 | 0.34 (0.86) | 0.69 | 0.45 | 0.44 |

| Missing | 605 | 8.26 (3.81) | 0.03 | 2322 | 0.23 (1.60) | 0.88 | 857 | − 4.93 (2.45) | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.16 |

| Getting needed care (N = 13,787) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 322 | 1.28 (1.61) | 0.42 | 1661 | 0.69 (0.60) | 0.25 | 731 | 2.05 (0.97) | 0.03 | 0.68 | 0.67 |

| Missing | 530 | 4.98 (2.83) | 0.07 | 2100 | − 0.61 (1.16) | 0.59 | 810 | − 5.75 (1.90) | 0.003 | 0.37 | 0.61 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Radiation | 685 | − 2.26 (1.22) | 0.06 | 3526 | 0.52 (0.48) | 0.27 | 1547 | 2.43 (0.79) | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.001 |

| Missing | 530 | − 2.13 (3.56) | 0.55 | 2100 | − 0.94 (1.36) | 0.49 | 810 | − 5.00 (2.25) | 0.02 | 0.85 | 0.31 |

| Physician communication (N = 13,589) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 335 | − 0.42 (1.18) | 0.71 | 1620 | 0.41 (0.49) | 0.39 | 650 | 1.09 (0.81) | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| Missing | 580 | 1.21 (2.05) | 0.55 | 2151 | 0.97 (0.94) | 0.29 | 749 | 1.47 (1.59) | 0.35 | 0.55 | 0.07 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Radiation | 710 | 0.28 (0.89) | 0.75 | 3470 | − 0.03 (0.39) | 0.92 | 1381 | 0.62 (0.66) | 0.34 | 0.72 | 0.77 |

| Missing | 580 | 2.63 (2.59) | 0.30 | 2151 | 0.06 (1.11) | 0.95 | 749 | 0.52 (1.87) | 0.77 | 0.96 | 0.17 |

| Getting needed prescription drugs (N = 12,614) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 323 | 0.97 (1.53) | 0.52 | 1523 | 0.05 (0.56) | 0.92 | 574 | 0.32 (0.97) | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.38 |

| Missing | 594 | − 2.75 (2.68) | 0.30 | 2088 | 1.13 (1.08) | 0.29 | 723 | 0.35 (1.90) | 0.85 | 0.52 | 0.56 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Radiation | 678 | 0.93 (1.18) | 0.42 | 3202 | 0.34 (0.45) | 0.45 | 1199 | 0.50 (0.80) | 0.63 | 0.49 | 0.61 |

| Missing | 594 | − 2.82 (3.39) | 0.40 | 2088 | 1.71 (1.27) | 0.17 | 723 | 0.71 (2.26) | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.60 |

| Overall care rating (N = 15,174) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 353 | 0.59 (1.27) | 0.64 | 1839 | 0.65 (0.48) | 0.18 | 768 | 1.61 (0.66) | 0.01 | 0.65 | 0.40 |

| Missing | 613 | 1.29 (2.26) | 0.56 | 2365 | 0.44 (0.93) | 0.63 | 856 | − 1.61 (1.30) | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.69 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Radiation | 733 | − 0.29 (0.97) | 0.76 | 3902 | 0.09 (0.38) | 0.80 | 1607 | 0.91 (0.53) | 0.08 | 0.72 | 0.34 |

| Missing | 613 | − 0.49 (2.80) | 0.86 | 2365 | − 0.67 (1.09) | 0.53 | 856 | − 3.00 (1.53) | 0.05 | 0.43 | 0.54 |

| Health plan rating (N = 15,682) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 376 | 0.15 (1.21) | 0.90 | 1874 | 0.46 (0.50) | 0.35 | 765 | 0.35 (0.81) | 0.66 | 0.83 | 0.78 |

| Missing | 652 | 2.19 (2.11) | 0.30 | 2415 | 0.05 (0.95) | 0.95 | 865 | − 1.36 (1.58) | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.83 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Radiation | 798 | − 1.25 (0.91) | 0.17 | 4041 | 0.07 (0.39) | 0.85 | 1618 | 0.99 (0.65) | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.04 |

| Missing | 652 | − 0.61 (2.65) | 0.81 | 2415 | − 0.72 (1.13) | 0.52 | 865 | − 0.08 (1.86) | 0.96 | 0.18 | 0.22 |

| Physician rating (N = 13,635) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 335 | − 1.82 (1.09) | 0.09 | 1626 | 0.26 (0.45) | 0.56 | 645 | 0.68 (0.71) | 0.33 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Missing | 576 | − 0.63 (1.92) | 0.74 | 2160 | 1.19 (0.86) | 0.16 | 747 | 0.14 (1.38) | 0.91 | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| Radiation: No/Unknown (ref) | |||||||||||

| Radiation | 709 | 0.08 (0.83) | 0.91 | 3497 | − 0.16 (0.36) | 0.64 | 1382 | 0.75 (0.57) | 0.18 | 0.77 | 0.55 |

| Missing | 576 | 3.19 (2.40) | 0.18 | 2160 | 0.33 (1.02) | 0.74 | 747 | 0.28 (1.63) | 0.86 | 0.45 | 0.08 |

CAHPS Consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems, GED general education development, HS high school, int. interaction, NHA non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, NHB non-Hispanic Black or African American, NHW non-Hispanic white, ref referent, SE standard error, SEER Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program

Missing values: Getting care quickly composite (2963); Getting needed care composite (4379); Physician communication composite (4548); Getting needed prescription drugs composite (5722); Overall care rating (2890); Health plan rating (2402); Physician rating (4509); other unspecified/unknown/multi-racial (194); education (1147)

Case-mix adjustments for years 1999–2019: Age at CAHPS survey (65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, ≥ 85); General health status (excellent/very good, good, fair/poor); Received help responding (no, yes); Proxy answered questions for respondent (no, yes)

Additional adjusted covariates: Age at diagnosis (continuous); Mental health status (excellent/very good; good; fair/poor; missing); years from diagnosis to CAHPS survey (continuous); Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) multimorbidity (continuous); CAHPS survey year (continuous); Medicare plan type (other [prescription drug plan {PDP} or Medicare Advantage {MA}], fee-for-service Medicare); area-level poverty (0– < 20% poverty; 20–100% poverty; unknown/missing); race/ethnicity (NHW, NHB, NHA, Hispanic), extent of disease (localized; regional; distant), chemotherapy (no/unknown; chemotherapy; missing), radiation (no/unknown; radiation; missing)

Borderline cases for ER status (13) were excluded

Predictors and stratifications are mutually adjusted

Bold font indicates statistically significant with corresponding p < .05

Survivors with college degrees who had radiation reported significantly higher mean scores for Getting Needed Care (β = 2.43, SE = 0.79, p = 0.002) compared to college graduates who had no/unknown radiation use, while the main effect for this association was not significant among survivors reporting less than a high school education (p-interaction = 0.001). Survivors treated with radiation and with a high school/GED/some college education also reported higher mean scores for Getting Needed Care compared to survivors with the same education and with no/unknown radiation treatment, although the associations were not significant. The interaction for this association was significant (p-interaction = 0.01). Although the beta coefficients for Health Plan Ratings among survivors with less than a high school education and survivors with college degrees were not significant, the interaction between them and radiation use was significant (p-interaction = 0.04).

Additional stratifications of area-level poverty and medicare plan type

Supplement B depicts the relationships between clinical breast cancer characteristics and CAHPS quality of care outcomes stratified by area-level poverty. Survivors living in poverty and diagnosed with regional breast cancer reported significantly higher mean for Physician Rating (β = 2.25, SE = 0.96, p = 0.01) compared to survivors living in poverty with localized disease; the main effect for this association was not significant among survivors not living in poverty with regional disease at diagnosis (p-interaction = 0.04). Interestingly, survivors who do not live in poverty with ER− status breast cancer reported significantly lower mean scores for Getting Needed Prescription Drug(s) (β = − 1.31, SE = 0.61, p = 0.03) compared to ER + breast cancer survivors who do not live in poverty. The main effect for this relationship was not significant among survivors living in poverty (p-interaction = 0.006).

Supplement C depicts the associations between clinical breast cancer characteristics and CAHPS outcomes stratified by Medicare plan type. Survivors who reported other Medicare plans (PDP, MA) and treated with radiation reported significantly higher mean scores for Getting Needed Care (β = 0.97, SE = 0.47, p = 0.03) compared to survivors with other Medicare plans who used no/unknown radiation; the main effect for this relationship was not significant among survivors using FFS Medicare plans (p-interaction = 0.01).

Discussion

We examined differences in the relationships between clinical cancer characteristics and survivorship care experiences among older female breast cancer survivors. To identify potential disparities among vulnerable groups, we additionally stratified associations by race/ethnicity, and measures of socioeconomic position. Overall, survivors with regional cancer at diagnosis or treated with chemotherapy reported significantly higher Getting Needed Care scores compared to those with localized breast cancer and who had no/unknown chemotherapy use, respectively. Results were similar for Overall Care Ratings among women treated with chemotherapy. Conversely, women diagnosed with distant breast cancer versus localized cancer at diagnosis reported significantly lower mean scores for Physician Communication. Race/ethnicity, education, and area-level poverty significantly modified several associations between stage, estrogen receptor status, treatments, and various CAHPS outcomes.

To the best our knowledge, only one prior study has evaluated the association between clinical cancer characteristics and quality of survivorship care based on SEER-CAHPS outcomes [21]. In this study, cancer survivors with breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer completed a CAHPS survey within one year prior to death, and survivors with regional disease at diagnosis were significantly less likely to report excellent Physician Ratings compared to those with localized disease. Conversely, those with distant disease at diagnosis were significantly more likely to report excellent Specialist Physician ratings compared to the cancer survivors with localized disease [21]. Differences between our study results for stage at diagnosis and results observed by Halpern et al. [21] could be attributed to differences in study design and population. Furthermore, the study by Halpern et al. [21] did not evaluate the impact of tumor receptor status or treatment types. As more cancer patients are living with metastatic disease due to advancements in cancer treatments [27], particularly among women diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer [28, 29], additional research studies are needed to examine how survivorship care experiences and the quality of this care among this population may be impacted by clinical cancer characteristics and treatments.

The current study contributes to the literature by targeting racial/ethnic disparities in the relationship between clinical breast cancer characteristics at diagnosis and post-diagnosis survivorship care experiences. Minority women, including NHB and Hispanic women, are more likely to be diagnosed with ER− breast cancer and more advanced stage at diagnosis which are more difficult to treat [4–6]. In the current study, differences in survivorship care by stage at diagnosis and treatment type existed among certain racial/ethnic groups but not others, demonstrating significant interactions between NHB and NHW survivors with regional disease and between NHA and NHW survivors treated with chemotherapy or radiation. Interestingly, NHB survivors with regional stage reported significantly higher Overall Care and Physician Rating scores compared to NHB survivors with localized disease. Regarding treatment, NHA survivors using chemotherapy or radiation reported higher mean scores for getting care quickly and getting needed care compared to NHA survivors with no/unknown chemotherapy or radiation use, respectively. Future research should include larger numbers of breast cancer survivors from racial/ethnic minority groups to determine if the direction and impact of these disparities exist outside of Medicare beneficiary samples.

Lastly, we examined the effect modification by socioeconomic position and observed across CAHPS outcomes, survivors with advanced stage or treated with chemotherapy and who reported less than a high school education generally exhibited lower mean scores for Physician Communication, Overall Care Ratings, and Physician Rating. Educational attainment remains a prominent social factor directly related to healthcare quality and access [30, 31]. The direction of these findings based on education has been consistent in other SEER-CAHPS analyses, showing that those with lower educational attainment are at greater likelihood of reporting lower care quality experiences compared to those with higher educational attainment [21, 32]. Interestingly, among women living in poverty, survivors with regional stage or ER− tumors reported higher scores for Physician Ratings and Getting Needed Prescription Drug(s) compared to survivors with localized or ER + subtypes, respectively. Our study results by socioeconomic position should be further evaluated utilizing additional measures of individual level data for socioeconomic status.

Strengths and limitations

The SEER-CAHPS data linkage allows for the analysis of a national probability-recruited sample of cancer patients and survivors coinciding with SEER clinical cancer characteristics and CAHPS survey of survivorship care experience ratings. This data linkage provided ample statistical strength to determine if barriers exist in survivorship care experiences among older breast cancer survivors by tumor characteristics, treatment, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors. Despite this, the current study may not be generalizable to the all older female breast cancer population in the US [33] such as those who did not complete a CAHPS survey or those who are not Medicare beneficiaries. There were several outcomes that were excluded from the analyses based on high missingness (> 35%) such as specialist rating, times visited specialist, number of times visited emergency room, and customer service score, that may have provided insight into survivorship care experiences among this sample. The variable regarding chemotherapy has been known to be biased, as there is evidence that those who SEER identified as “no/unknown” may indicate a true disuse of chemotherapy, or it was missed by the SEER registry because treatment occurred outside hospital settings. Variables for chemotherapy and other treatment(s) for a related diagnosis are based on the first course of treatment in SEER data files, and therefore, may not reflect ongoing or additive treatment regimens [34]. These biases reflect low sensitivity but high specificity but remain relative to gold-standard Medicare claims data, which should be utilized in future research, when applicable. Additionally, Noone and colleagues [34] recommend augmenting SEER-CAHPS data with other data resources for analyses involving chemotherapy use comparisons, including medical record abstraction in addition to Medicare claims data. There may exist confounding variables that were unaccounted for in the current analysis that may explain at least a portion of the disparities in cancer survivorship care experience like genetic mutations, detailed family history, and more individualized socioeconomic metrics to analyze poverty status instead of the SEER-provided area-level poverty variable by neighborhood, as it may introduce misclassification. Additionally, CAHPS employs the use of proxy responders to complete surveys on behalf of their respondents. Although only 3.0% of the current sample reported using proxies, this must be considered as proxy answers may provide less accurate information. Despite such limitations, SEER-CAHPS data remains an important resource in identifying disparities in breast cancer survivorship care experiences among Medicare beneficiaries, especially among racial/ethnic and other sociodemographic minority groups.

Conclusions

While some positive findings were observed among survivors with regional cancer and treated with chemotherapy, women diagnosed with distant breast cancer versus localized cancer reported lower mean scores for Physician Communication. Race/ethnicity and measures of socioeconomic position significantly modified several associations between stage, estrogen receptor status, treatments, and various CAHPS outcomes. These study findings can be used to inform survivorship care providers treating women diagnosed with more advanced stage and aggressive disease. The disparities we observed among minority groups and by socioeconomic status should be further evaluated in future research as these interactions could impact long-term outcomes, including survival. Future studies utilizing related data should focus on evaluating both significant and nonsignificant findings to truly identify patterns in breast cancer survivorship care experiences among similar populations.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the process through which SEER-CAHPS 2000–2019 participants were excluded for the current analyses

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Johns Hopkins Ho-Ching Wang Memorial Faculty Award. Kate E Dibble received research support from the National Cancer Institute (T32CA009314) Cancer Epidemiology, Prevention, and Control training program. The authors would like to acknowledge the guidance of the NCI SEER-CAHPS program and Dr. Michelle Mollica for their assistance regarding analytic approaches used in this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the Johns Hopkins Ho-Ching Wang Memorial Faculty Award. Kate E Dibble received research support from the National Cancer Institute (T32CA009314) Cancer Epidemiology, Prevention, and Control training program. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Ho-Ching Wang Memorial Faculty Award, Avonne E Connor, National Cancer Institute, T32CA009314, Kate E Dibble

Abbreviations

- CAHPS

Consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems

- CMS

Centers for medicare & medicaid services

- NCI

National cancer institute

- NHA

Non-hispanic asian

- NHB

Non-hispanic black

- NHW

Non-hispanic white

- SE

Tandard error

- SEER

Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results

- US

United States

Footnotes

Conflict of interests The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Code availability The code generated for the current study is available from the corresponding author.

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-023-06948-6.

Data availability

The dataset(s) were obtained via an application process via NCI SEER-CAHPS data resource and can be accessed from https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seer-cahps/

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute (NCI). Survivorship. 2021; Available from https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/survivorship

- 2.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, Jemal A, Kramer JL, Siegel RL (2019) Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 69(5):363–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trentham-Dietz A, Hunter Chapman C, Bird J, Gangnon RE (2021) Recent changes in the patterns of breast cancer as a proportion of all deaths according to race and ethnicity. Epidemiology 32(6):904–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendrick RE, Monticciolo DL, Biggs KW, Malak SF (2021) Age distributions of breast cancer diagnosis and mortality by race and ethnicity in US women. Cancer 127(23):4384–4392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Cancer Society (ACS). Triple-negative breast cancer. 2022; Available from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/about/types-of-breast-cancer/triple-negative.html

- 6.Zavala VA, Bracci PM, Carethers JM et al. (2021) Cancer health disparities in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. Brit J Cancer 124:315–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeder-Hayes KE, Wheeler SB, Mayer DK (2015) Health disparities across the breast cancer continuum. Semin Oncol Nurs 31(2):170–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daly B, Olopade O (2015) A perfect storm: How tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin 65(3):221–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krok-Schoen JL, Naughton MJ, Noonan AM, Pisegna J, DeSalvo J, Lustberg MB (2020) Perspectives of survivorship care plans among older breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. Cancer Control 27(1):1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke NJ, Napoles TM, Banks PJ, Orenstein FS, Luce JA, Joseph G (2016) Survivorship care plan information needs: perspectives of safety-net breast cancer patients. PLoS ONE 11(12):e0168383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tompkins C, Scanlon K, Scott E, Ream E, Harding S, Armes J (2016) Survivorship care and support following treatment for breast cancer: A multi-ethnic comparative qualitative study of women’s experiences. BMC Health Serv Res 16:401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Surbone A, Halpern MT (2016) Unequal cancer survivorship care: Addressing cultural and sociodemographic disparities in the clinic. Support Care Cancer 24(12):4831–4833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lovelace DL, McDaniel LR, Golden D (2019) Long-term effects of breast cancer surgery, treatment, and survivor care. J Midwifery Womens Health 64(6):713–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Ross RN et al. (2018) Disparities in breast cancer survival by socioeconomic status despite Medicare and Medicaid insurance. Millbank Q 96(4):706–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halpern MT, McCabe MS, Burg MA (2016) The cancer survivorship journey: Models of care, disparities, barriers, and future directions. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 35:231–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dreyer MS, Nattinger AB, McGinley EL, Pezzin LE (2018) Socioeconomic status and breast cancer treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat 167(1):1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griggs JJ, Culakova E, Sorbero MES et al. (2007) Effect of patient socioeconomic status and body mass index on the quality of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 25(3):277–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Institute (NCI). SEER-CAHPS linked data resource. 2022; Available from: https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seer-cahps/

- 19.Chawla N, Urato M, AMbs A et al. (2015) Unveiling SEER-CAHPS: A new data resource for quality of care research. J Gen Intern Med 30(5):641–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halpern MT, Urato MP, Kent EE (2017) The health care experience of patients with cancer during the last year of life: analysis of the SEER-CAHPS data set. Cancer 123(2):336–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Damiano PC, Elliott M, Tyler MC (2004) Differential use of the CAHPS 0–10 global rating scale by Medicaid and commercial populations. Health Serv Outcomes Res Method 5:193–205 [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Cancer Institute (NCI). Approaches to using CAHPS items and composites. 2022; Available from: https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seer-cahps/researchers/approaches_guidance.html

- 23.Paddison CAM, Elliot MC, Haviland AM et al. (2013) Experiences of care among Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD - Medicare Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey results. Am J Kidney Dis 61(3):440–449. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Cancer Institute (NCI). Case-mix adjustment guide. 2022; Available from: https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seer-cahps/resea rchers/adjustment_guidance.html

- 25.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Chronic conditions. 2022; Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Chronic-Conditions/CC_Main

- 26.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. 2019: College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tometich DB, Hyland KA, Soliman H, Jim HSL, Oswald L (2020) Living with metastatic cancer: A roadmap for future research. Cancers 12(12):3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greco C (2022) The uncertain presence: Experiences of living with metastatic breast cancer. Med Anthropol 41(2):129–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallicchio L, Devasia TP, Tonorezos E, Mollica MA, Mariotto A (2022) Estimation of the numbers of individuals living with metastatic cancer in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 10.1093/jnci/djac158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Cancer Society (ACS). Breast cancer facts and figures 2019–2020. 2019; Available from: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-figures.html

- 31.Coughlin SS (2019) Social determinants of breast cancer risk, stage, and survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat 177:537–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]