Abstract

BACKGROUND

Diaphragmatic paralysis is typically associated with phrenic nerve injury. Neonatal diaphragmatic paralysis diagnosis is easily missed because its manifestations are variable and usually nonspecific.

CASE SUMMARY

We report a 39-week-old newborn delivered via vaginal forceps who presented with tachypnea but without showing other birth-trauma-related manifestations. The infant was initially diagnosed with pneumonia. However, the newborn still exhibited tachypnea despite effective antibiotic treatment. Chest radiography revealed right diaphragmatic elevation. M-mode ultrasonography revealed decreased movement of the right diaphragm. The infant was subsequently diagnosed with diaphragmatic paralysis. After 4 weeks, tachypnea improved. Upon re-examination using M-mode ultrasonography, the difference in bilateral diaphragmatic muscle movement was smaller than before.

CONCLUSION

Appropriate use of M-mode ultrasound to quantify diaphragmatic excursions could facilitate timely diagnosis and provide objective evaluation.

Keywords: Diaphragmatic paralysis, M-mode ultrasonography, Birth trauma, Newborn, Case report

Core Tip: Diaphragmatic paralysis is typically caused by phrenic nerve injury in the context of birth-related trauma or cardiothoracic surgery. Diagnosis of diaphragmatic paralysis is easily missed because its signs are usually nonspecific. The infant in this case had a lung infection but without showing other manifestations due to birth-related trauma. The infant exhibited tachypnea despite effective antibiotic treatment. Chest radiography revealed an elevated right hemidiaphragm. Diagnosis of diaphragmatic paralysis was confirmed by ultrasonography, which revealed decreased motion of the right diaphragm. Appropriate use of M-mode ultrasound to quantify diaphragmatic excursions could facilitate timely diagnosis and provide objective evaluation.

INTRODUCTION

Diaphragmatic paralysis is typically caused by phrenic nerve injury in the context of birth-related trauma or cardiothoracic surgery[1]. Neonatal diaphragmatic paralysis is usually unilateral, commonly involving the right side[2]. Diaphragmatic paralysis diagnosis is easily missed because its manifestations are variable and usually nonspecific. In this report, we describe neonatal diaphragmatic paralysis and its diagnosis using M-mode ultrasonography.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 39-week-old newborn was admitted to the hospital for tachypnea.

History of present illness

The newborn, delivered via vaginal forceps, presented with tachypnea but without showing other manifestations due to birth trauma.

History of past illness

The newborn had no remarkable past illness.

Personal and family history

There were no notable medical issues in the newborn’s family.

Physical examination

The infant exhibited tachypnea, with a respiratory rate of 70 breaths/minutes. The findings of the nervous system examination were unremarkable, without noting other manifestations due to birth trauma.

Laboratory examinations

Laboratory test results showed an increased infection index.

Imaging examinations

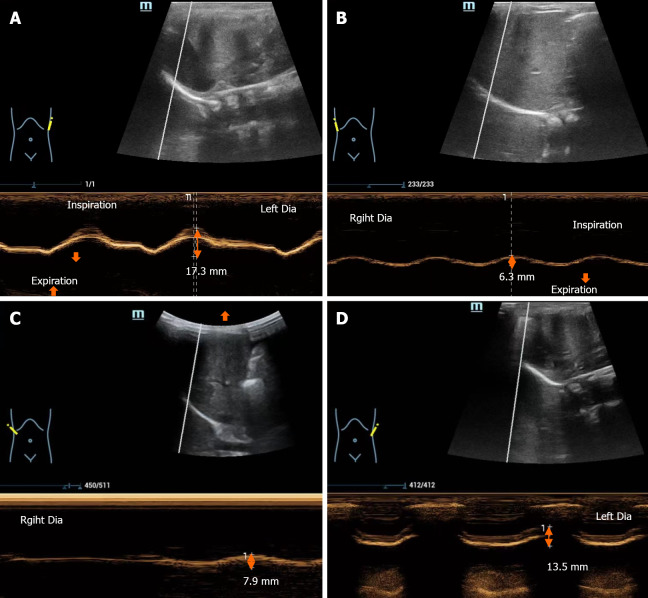

Chest radiography revealed right diaphragmatic elevation and increased patch density in the upper field of the left lung (Figure 1). M-mode ultrasonography revealed normal movement of the left diaphragm (Figure 2A) and decreased movement of the right diaphragm in the supine position (Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Chest radiography revealed right diaphragmatic elevation and increased patch density in the upper field of the left lung.

Figure 2.

Image changes in M-mode ultrasonography. A: The right diaphragm shows decreased motion with respiration; B: The left diaphragm shows normal excursion with phases of respiration; C: After 4 weeks, the decreased motion of the right diaphragm shows improvement; D: After 4 weeks, the left diaphragm shows normal motion during respiration. The arrows indicate the movement of the diaphragm.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The infant was ultimately diagnosed with pneumonia and diaphragmatic paralysis.

TREATMENT

The infant was administered a course of antibiotic treatment. One week later, re-examination by chest radiography showed no infection. Since the levels of other laboratory infection indicators were also normal, antibiotic administration was stopped. Due to a respiration rate of 70 breaths/minutes, the infant was initiated on nasal high-flow oxygen therapy at a flow rate of 8 L/minutes. However, after 1 week, the infant continued to exhibit tachypnea. Thus, breathing support was continued for a further 1 week.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Four weeks later, there was improvement in tachypnea. Upon reassessment using M-mode ultrasonography, the difference in bilateral diaphragmatic muscle movement was noted to be smaller compared with that before (Figure 2C and D).

DISCUSSION

Diaphragmatic paralysis is typically caused by phrenic nerve injury sustained in the context of birth-related trauma or cardiothoracic surgery[1]. Given weak intercostal muscles and increased mediastinal mobility in infants and young children, adequate ventilation is almost totally dependent on diaphragmatic function initially[3]. Consequently, diaphragmatic paralysis affects breathing more severely in children even with unilateral paralysis. Consistent with this, infants tolerate diaphragmatic paralysis much less effectively than do older children[4,5]. Unfortunately, the diagnosis of diaphragmatic paralysis is easily missed because its manifestations are variable and usually nonspecific. Clinical manifestations include unexplained difficulty with mechanical ventilation, asymmetric breathing patterns, abnormal upper abdominal movements, as well as recurrent pneumonia and/or tachypnea.

Neonatal diaphragmatic paralysis is usually unilateral, commonly involving the right side[2]. Regarding diaphrag-matic paralysis, chest radiography may show persistent hemidiaphragmatic elevation. Most notably, the hemidiaphragm position is considered atypical when the right hemidiaphragm is more than two rib spaces higher than the left hemidiaphragm, or when the left hemidiaphragm is more than one intercostal space higher than the right hemidiaphragm[6]. However, given the wide range of hemidiaphragm positions considered to be normal, such asymmetries are not considered to be specific signs[7]. Instead, the diagnosis of diaphragmatic paralysis relies either on echocardiography or fluoroscopy. Although fluoroscopy is radiative, ultrasound involves no radiation exposure. Using M-mode ultrasonography detection, the amplitude, duration and velocity of diaphragmatic excursions can be recorded, providing a quantified, objective evaluation as a reference to compare between subsequent improvement and deterioration. Regarding right hemidiaphragmatic motion recording, the liver is used as a window, and the probe is placed between the mid-clavicular and mean axillary lines. Considering left hemidiaphragmatic motion recording, the spleen is used as a window; the probe is placed subcostally between the anterior and posterior axillary lines[8]. M-mode ultrasonography can classify diaphragmatic movement as normal, decreased, absent or paradoxical (Table 1)[9].

Table 1.

Classification of diaphragm motion

|

Classification

|

Definition

|

| Normal motion | The amplitude of diaphragmatic excursion is > 4 mm, and the difference of amplitude between the hemidiaphragms is < 50% |

| Decreased motion | The amplitude of diaphragmatic excursion is ≤ 4 mm and the difference of amplitude is > 50% |

| Absent motion | Absent motion is considered by a flat line trace |

| Paradoxical motion | Paradoxical motion is considered when diaphragm moves away from the transducer in inspiration |

Diaphragmatic paralysis in this case was caused by phrenic nerve injury caused by birth-related trauma. The infant in this case had a lung infection but without showing other manifestations due to birth-related trauma, such as brachial plexus palsy. The infant was initially diagnosed with pneumonia and treated accordingly. However, since the infant still exhibited tachypnea despite effective antibiotic treatment and chest radiography revealed an elevated right hemidiaphragm, diaphragmatic paralysis was suspected. The diagnosis was confirmed by ultrasonography, which revealed decreased motion of the right diaphragm.

CONCLUSION

Neonatal diaphragmatic paralysis can be easily misdiagnosed. Appropriate use of M-mode ultrasonography to quantify diaphragmatic excursions could facilitate a timely diagnosis and provide an objective evaluation.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade B

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Ghannam WM S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Chen YL

Contributor Information

Yan Zeng, Department of Pediatrics, People's Hospital of Deyang City, Deyang 618000, Sichuan Province, China.

Pei Luo, Department of Ultrasound, People's Hospital of Deyang City, Deyang 618000, Sichuan Province, China.

Di-Ran Zhao, Department of Ultrasound, People's Hospital of Deyang City, Deyang 618000, Sichuan Province, China.

Feng-Yang Wang, Department of Pediatrics, People's Hospital of Deyang City, Deyang 618000, Sichuan Province, China.

Bin Song, Department of Nephrology, People's Hospital of Deyang City, Deyang 618000, Sichuan Province, China. sb8052@126.com.

References

- 1.Rizeq YK, Many BT, Vacek JC, Reiter AJ, Raval MV, Abdullah F, Goldstein SD. Diaphragmatic paralysis after phrenic nerve injury in newborns. J Pediatr Surg. 2020;55:240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Volpe JJ. Injuries of Extracranial, Cranial, Intracranial, Spinal Cord, and Peripheral Nervous System Structures. Volpe's Neurology of the Newborn (Sixth Edition). Elsevier, 2018: 1093.e5-1123.e5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mok Q, Ross-Russell R, Mulvey D, Green M, Shinebourne EA. Phrenic nerve injury in infants and children undergoing cardiac surgery. Br Heart J. 1991;65:287–292. doi: 10.1136/hrt.65.5.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mickell JJ, Oh KS, Siewers RD, Galvis AG, Fricker FJ, Mathews RA. Clinical implications of postoperative unilateral phrenic nerve paralysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1978;76:297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith CD, Sade RM, Crawford FA, Othersen HB. Diaphragmatic paralysis and eventration in infants. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1986;91:490–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCauley RG, Labib KB. Diaphragmatic paralysis evaluated by phrenic nerve stimulation during fluoroscopy or real-time ultrasound. Radiology. 1984;153:33–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.153.1.6473801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander C. Diaphragm movements and the diagnosis of diaphragmatic paralysis. Clin Radiol. 1966;17:79–83. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(66)80128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boussuges A, Rives S, Finance J, Brégeon F. Assessment of diaphragmatic function by ultrasonography: Current approach and perspectives. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:2408–2424. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i12.2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sehgal A, Fernando S, Ditchfield M. M-Mode Imaging of the Diaphragm in Phrenic Nerve Palsy Due to Birth Trauma. J Pediatr. 2022;246:281–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]