Systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials provide an evidence base for treatment but too often fail to give adequate information on long term outcomes. Elphick and colleagues discuss the limitations of the systematic review of randomised controlled trials for patients with chronic or lifelong diseases and suggest that long term observational studies have a place in the evaluation of the benefits and risks of treatment

Synthesis of evidence from systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials is considered the gold standard when evaluating the effectiveness of treatments, yet systematic reviews do not always place as much emphasis on information about adverse effects or safety issues.1,2 In people with chronic, or lifelong, diseases long term outcomes are particularly important but are much less likely to be evaluated in randomised controlled trials. We discuss the results of a recent systematic review of randomised controlled trials of antibiotic therapy in cystic fibrosis, which provided preliminary information about antibiotic resistance but not about other adverse effects. Although the review suggested that this finding should be investigated by a further clinical trial, we discuss why this may be neither the most feasible nor the most efficient study design with which to evaluate long term outcomes in lifelong diseases.

Summary points

A systematic review suggested that there was an increase in antibiotic resistance in patients treated with one compared with two antibiotics

Systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials are often unable to provide adequate information about long term outcomes, which are important for people with chronic diseases

A tension exists in randomised controlled trials between evaluating short term outcomes, which may indicate a need to change practice, and continuing the trial for sufficient time to evaluate long term outcomes

Databases specialising in a particular disease can play a part in capturing information on patients prospectively, provided the clinical questions are established from the outset

To adequately evaluate benefits and risks of treatment for chronic diseases, systematic reviews should consider data from observational studies as well as from randomised controlled trials

Methods

We carried out a systematic review to assess the effectiveness of single compared with combination intravenous antibiotic therapy to treat respiratory exacerbations in people with cystic fibrosis.3 Here we focus on the comparison of a β lactam antibiotic with a β lactam and aminoglycoside combination. To investigate further possible long term adverse effects of these antibiotics we undertook a search of Medline from 1966 to identify studies that investigated toxicity related to aminoglycosides in patients with cystic fibrosis.

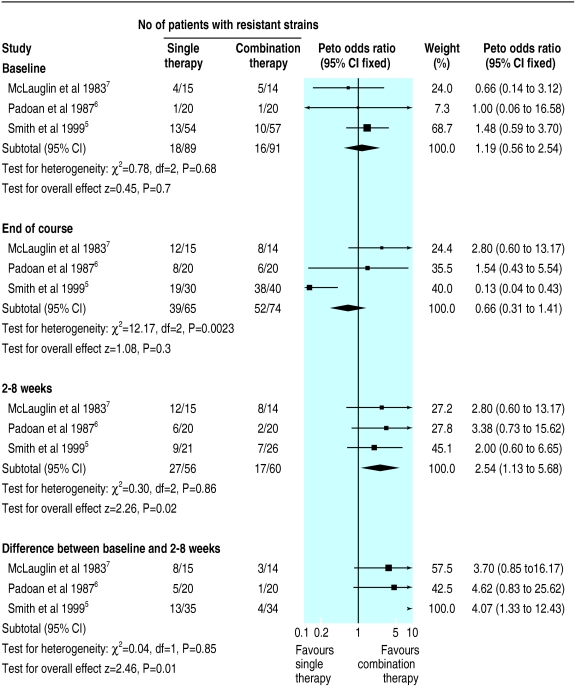

We included nine randomised controlled trials (386 patients) eight of which compared a β lactam antibiotic with a β lactam and aminoglycoside. Overall the quality of the methods was poor, and meta-analysis was not possible for most of the outcome measures.4 We found no significant differences between the therapies for lung function, symptom scores, and adverse effects. Three trials assessed the development of resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.5–7 We found no difference between the groups at baseline and immediately after treatment. Two to eight weeks after treatment, single therapy was associated with an increased number of patients whose sputum grew resistant strains (odds ratio 2.54, 95% confidence interval 1.13 to 5.68). The change in number of patients with resistant strains from baseline to follow up also showed a difference favouring combination treatment (4.07, 1.33 to 12.43; figure).

Use of antibiotics

Intravenous antibiotics are widely used to treat respiratory exacerbations in patients with cystic fibrosis, particularly when associated with P aeruginosa infection. The type, duration, and number of antibiotics used varies. A survey conducted in the United Kingdom and Ireland in 1993 found that 5 of 26 clinicians dealing with cystic fibrosis used a β lactam antibiotic alone as intravenous therapy for acute respiratory exacerbations due to P aeruginosa.8 The proportion of centres using monotherapy is likely to have decreased since then, as guidelines from the UK Cystic Fibrosis Trust recommended that two intravenous antibiotics should be used for a minimum of 10 days.9 This recommendation was made before the publication of our systematic review. The evidence to support it came from a study showing that a high proportion of children in one cystic fibrosis clinic had an identical strain of P aeruginosa, presumably transmitted by cross infection.10 The authors speculated that the policy of using ceftazidime monotherapy may have contributed to the emergence of this resistant organism. Although this study did not address the efficacy of single compared with combination antibiotic therapy it has been cited in influential articles that advocate combination therapy.9,11

Antibiotic resistance

Randomised controlled trials of antibiotics often do not consider resistance as an outcome because it is difficult to measure, is beyond the time frame of most clinical trials, and usually affects patients in the community who are outside the trial.12 The first two of these difficulties apply to cystic fibrosis, although the third is less relevant as emergence of a resistance within an individual patient has important long term consequences for that individual and his or her future treatment. We concluded in our review that the results concerning antibiotic resistance were preliminary and that further trials of single compared with combination antibiotic therapy were needed in cystic fibrosis. Given that our findings will add weight to the recommendations in support of combination therapy, it seems unlikely that such trials will now be possible.

In contrast with the stated advantages of combination therapy, usually with a β lactam and aminoglycoside, the theoretical arguments in favour of monotherapy with a β lactam include reduced costs, convenience, and a reduction in aminoglycoside related adverse effects. Respiratory exacerbations requiring intravenous antibiotic treatment may occur frequently from early childhood in patients with cystic fibrosis. Some clinics use regular courses of intravenous treatment every three months in patients with P aeruginosa.13 When considering these therapies in a chronic disease such as cystic fibrosis, consideration should be given not only to the short term outcomes, measurable at the end of treatment, but also to the long term outcomes, which may represent the cumulative effects of treatment over many years. The long term cumulative adverse effects of aminoglycosides are nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity. We searched Medline from 1966 to identify studies that investigated toxicity related to aminoglycosides in patients with cystic fibrosis.

Long term adverse effects

We found no longitudinal studies reporting on hearing or renal function in relation to cumulative doses of aminoglycoside. We did, however, find one cross sectional study on this subject.13,14 This study was from the first major cystic fibrosis centre to advocate intravenous β lactam and aminoglycoside every three months in patients with P aeruginosa.13 The study included 46 patients, with a mean of 20 cumulative courses of aminoglycoside. Nearly 40% of the patients had a creatinine clearance below normal, although there was no overt chronic nephrotoxicity. Two patients had a chronic hearing deficit that may have been drug related, and no chronic vestibulotoxicity was reported. A more recent study, which did not relate toxicity to cumulative dose of aminoglycoside, reported a series of 43 adults with cystic fibrosis in whom pure tone audiometry was performed. Bilateral sensorineural hearing loss for high frequency sounds consistent with aminoglycoside induced ototoxicity was detected in seven.15 We found two case reports of acute hearing loss in patients with cystic fibrosis related to treatment with aminoglycoside.11,16

We also examined the outcomes used to measure nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity. Some studies investigated aminoglycoside toxicity by measuring urinary excretion of β N-acetylglucosaminase as a marker of renal tubular damage and distortion product otoacoustic emissions as a marker of cochlear damage.14,17,18 Traditional methods for assessing renal function and hearing have been criticised for being insensitive and detecting only irreversible end organ damage. It has been suggested that monitoring of patients using urinary excretion of β N-acetylglucosaminase and distortion product otoacoustic emissions may detect subclinical toxicity related to aminoglycosides.14,17 However neither of these measures has been properly evaluated as surrogate markers for the definitive end points.

Inadequacies of randomised controlled trials

Numerous examples exist of the inadequacies of randomised controlled trials in assessing long term adverse effects of treatments in other chronic diseases. The use of inhaled corticosteroids in asthma has been associated with considerable benefits, but in children there are concerns about the long term effects, especially on growth. A Cochrane review investigated the effects of linear growth in children with asthma treated with inhaled beclomethasone.19 The review methods included a comprehensive search for randomised controlled trials, but only three were suitable for inclusion in the review. The longest study duration was 54 weeks. Although the results of the review found a significant decrease in linear growth over this time, it was unclear whether this would be sustained in the longer term, and the conclusions were therefore tentative. As childhood growth patterns are not uniform, a full evaluation of the effect of inhaled steroids on growth may need to consider inclusion of longer term, non-randomised studies.

The need to consider non-randomised studies for the assessment of adverse effects has recently been addressed in some Cochrane reviews. A systematic review of low dose oral corticosteroids compared with placebo or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis concluded that this therapy is highly effective.20 In the randomised controlled trials included in this review, long term adverse effects were not adequately addressed in either the treatment or the control groups. Because of this the reviewers searched for further studies to investigate medium and long term adverse effects of low dose steroids. In this part of the review they included eight additional trials and two matched cohort studies. In both of the cohort studies an increase in the incidence of adverse events was shown in the steroid treated group compared with the comparison group. Although this review recognised the need to examine studies other than randomised controlled trials to investigate long term adverse events, this was not included in the initial objectives of the review, and the methods did not include adverse events in the clinical outcomes.

Systematic reviews and lifelong diseases

We are faced with several dilemmas. In our systematic review of several small, short term clinical trials we found an increase in antibiotic resistance in patients treated with single compared with combination intravenous antibiotics. We concluded that these findings require further investigation by high quality clinical trials. In this example experimentation may be considered inappropriate (because the outcomes of interest are far in the future) or impossible (because of the reluctance of clinicians to participate).21 The reluctance of clinicians to participate may be successfully overcome, and the exponential increase in randomised controlled trials in cystic fibrosis over the past 30 years suggests that this is happening.22 However, because of prevailing medical opinion, reinforced by the tentative evidence from the systematic review, it seems unlikely that such clinical trials will be considered acceptable. Even if they were possible, to answer important questions about the safety and efficacy of treatment strategies clinical trials should compare repeated courses of treatment over several years. This leads to a tension between evaluating short term outcomes, which indicate a need to change practice, and continuing the trial for sufficient follow up time to evaluate long term outcomes. With a chronic disease that lasts for the lifetime of the patient it is hard to accept that all the important questions about treatment interventions will be answered by clinical trials. To address these questions, the role of other study designs such as population based cohort and case-control studies and analyses of epidemiological databases should be considered.

Reviewing data from observational studies

Disease databases such as cancer registries, which collect routine data, are invaluable for the documentation of incidence and prevalence of diseases and for use as a sampling frame for further studies. More specialised disease databases, which prospectively collect a range of clinical data, have also been established. A comprehensive database for patients with cystic fibrosis has been in existence for some years in the United States and has recently been established in the United Kingdom.23 As well as providing important information about disease demography, complications, and epidemiology, such databases can be used to capture information prospectively about patient outcomes and relate these to treatment interventions and environmental and other independent variables. However, to achieve this it is important that they are focused on specific clinical questions at conception so that relevant data—for example, adverse effects of treatments or clinical outcomes—can be collected prospectively.

Clinicians and patients need to be able to make informed judgments that balance the benefits and harms of treatments. Judgments are more easily made about short term effects by using randomised controlled trials, but the assessment of long term adverse effects requires a different study design. In making recommendations for primary research, rather than constantly advocating further randomised controlled trials, systematic reviewers should consider whether useful information could be obtained from well conducted observational studies, which may require less financial, clinical, and patient resources. Although the limitations of non-randomised comparisons are well recognised,20 we suggest that to adequately evaluate both benefits and risks of treatment, systematic reviews of chronic or lifelong diseases should explicitly review data from long term observational studies. Future methodological research should consider robust ways of integrating these data into the, now traditional, systematic review of randomised controlled trials.

Figure.

Studies comparing β lactam antibiotic with β lactam and aminoglycoside combination. Outcome is number of patients with resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Acknowledgments

We thank Mandy Bryant for her help with the literature search.

Footnotes

Funding: Core funding for the Cochrane Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders Group is from the NHS Executive R&D Programme and the UK Cystic Fibrosis Trust.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Li wan Po A, Herxheimer A, Poolsup N, Aziz Z. 8th Cochrane Colloquium abstract. Cape Town, South Africa. 2001. How do Cochrane reviewers address adverse effects of drug therapy? [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ernst E, Pittler M. Assessment of therapeutic safety in systematic reviews: literature review. BMJ. 2001;323:546. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7312.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elphick HE, Tan A. Cochrane Library. Issue 3. Oxford: Update Software; 2001. Single versus combination intravenous antibiotic therapy for people with cystic fibrosis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz K, Chalmers I, Hayes R, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias: dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effect in controlled clinical trials. JAMA. 1995;273:408–412. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith A, Doershuk C, Goldmann D, Gore E, Hilman B, Marks M, et al. Comparison of a beta-lactam alone versus beta-lactam and an aminoglycoside for pulmonary exacerbation in cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 1999;134:413–421. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Padoan R, Cambisano W, Constantini D, Crossignani R, Danza M, Giunta A. Ceftazidime monotherapy vs combined therapy in Pseudomonas pulmonary infections in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1987;648-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.McLaughlin F, Matthews W, Strieder D, Sullivan B, Taneja A, Murphy P, et al. Clinical and bacteriological responses to three antibiotic regimens for acute exacerbations of cystic fibrosis. J Infect Dis. 1983;147:559–567. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.3.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor R, Hodson M. Cystic fibrosis: antibiotic prescribing practices in the United Kingdom and Eire. Respir Med. 1993;87:535–539. doi: 10.1016/0954-6111(93)90010-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UK Cystic Fibrosis Trust's Antibiotic Group. Antibiotic treatment for cystic fibrosis. Bromley, Kent: Cystic Fibrosis Trust; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng K, Smyth RL, Govan JR, Doherty C, Winstanley C, Denning N, et al. Spread of beta-lactam-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a cystic fibrosis clinic. Lancet. 1996;348:639–642. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)05169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akbar A, Rees J, Nyamugunduru G, English M, Spencer D, Weller P. Aminoglycoside-association hypomagnesaemia in children with cystic fibrosis. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:783–785. doi: 10.1080/08035259950169116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leibovici L, Shraga I, Andreassen S. How do you choose antibiotic treatment? BMJ. 1999;318:1614–1618. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7198.1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frederiksen B, Lanng S, Koch C, Hoiby N. Improved survival in the Danish Center-treated cystic fibrosis patients: results of aggressive treatment. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1996;21:153–158. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(199603)21:3<153::AID-PPUL1>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulheran M, Degg C. Comparison of distortion product OAE generation between a patient group requiring frequent gentamicin therapy and control subjects. Br J Audiol. 1997;31:5–9. doi: 10.3109/03005364000000004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mulherin D, Fahy J, Grant W, Keogan M, Kavanagh B, FitzGerald M. Aminoglycoside induced ototoxicity in patients with cystic fibrosis. Ir J Med Sci. 1991;160:173–175. doi: 10.1007/BF02961666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scott C, Retsch-Bogart G, Henry M. Renal failure and vestibular toxicity in an adolescent with cystic fibrosis receiving gentamicin and standard-dose ibuprofen. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31:314–316. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godson C, Ryan M, O'Halloran D, Bourke S, Brady H, FitzGerald M. Investigation of aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity in cystic fibrosis patients. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1988;143:70–73. doi: 10.3109/00365528809090220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katbamna B, Homnick D, Marks J. Effects of chronic tobramycin treatment on distortion product otoacoustic emissions. Ear Hear. 1999;20:393–402. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199910000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharek PJ, Bergman DA, Ducharme F. Cochrane Library. Issue 4. Oxford: Update Software; 2001. Betamethasone for asthma in children: effects on linear growth. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gotsche PC, Johansen H. Cochrane Library. Issue 4. Oxford: Update Software; 2001. Short-term low-dose corticosteroids vs placebo and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black N. Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care. BMJ. 1996;312:1215–1218. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7040.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng K, Smyth RL, Motley J, O'Hea U, Ashby D. Randomized controlled trials in cystic fibrosis (1966-1997) categorized by time, design, and intervention. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;29:1–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(200001)29:1<1::aid-ppul1>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehta A. Further comments on fibrosing colonopathy study. Lancet. 2001;358:1546–1547. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06591-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]