Abstract

The persistent achievements of ionic liquids in various fields, including medicine and energy necessitate the efficient development of novel functional ionic liquids that exhibit favorable characteristics, alongside the development of practical and scalable synthetic methodologies. Ionic liquids are fundamentally understood as materials in which structure begets function, and the function and applicability of ILs is of utmost concern. It was recently reported that “full fluorosulfonyl” electrolyte is compatible with both the Li metal anode and the metal-oxide cathode that is crucial for the development of high-voltage rechargeable lithium-metal batteries. Inspired by these results, for the first time, we reported the synthesis of a series of ionic liquids with a sulfonyl fluoride motif using an highly effective and modular fluorosulfonylethylation procedure. Herein, we present a detailed analysis of novel sulfonyl fluoride-based ionic liquids paired with the hexafluorophosphate anion. We employed a combination of computational modeling and X-ray crystallographic studies to gain an in-depth understanding of their structure-property correlations.

The ability of sulfonyl (VI) fluorides to maintain a favorable equilibrium between reactivity and stability has resulted in their widespread use in chemical biology and medicinal chemistry. While efforts to develop sulfonyl fluoride intermediates are still in progress by synthetic chemists, their outstanding chemical stability under physiological conditions has elevated their prominence within the realm of chemical biology.1–4

Sulfonyl (VI) chlorides are popular SVI electrophiles among organic chemists, but due to the vulnerability of the SVI–Cl bond to reductive collapse, resulting in the formation of a SIV species and a chloride ion, the intended nucleophilic halide substitution event is frequently prevented by the annihilation of the sulfur electrophile. By contrast, only the substitution pathway is available when sulfur fluorides (e.g. R–SO2–F and SO2F2) are utilized.5 In contrast to their chloride analogs, sulfonyl fluorides demonstrate higher thermal and chemical stability. Under spatial and kinetic restrictions, sulfonyl fluorides exhibit outstanding electrophilic reactivity toward O– and N–nucleophilic substitutions while remaining stable to harsh reaction conditions.6 Although the chemistry of sulfonyl fluorides was discovered in the 1920s,7 it has garnered popularity in recent years as the reaction involving Sulfonyl (VI) Fluoride Exchange (SuFEx) are considered as a “clickable” reaction, indicted by Sharpless: “[SO2F] thereby attains a hallmark of click reaction function, remaining “invisible” under most conditions and coming to life only when desired”.5 In addition, Taulgoat et al. reported that sulfonyl fluorides can be readily transformed to their corresponding lithium sulfonates with LiOH.8 Lithium sulfonates (RSO3Li) have in fact great potentials as electrolytes for lithium-sulfur9 and lithium-polymer10 batteries.

Click chemistry is a conceptual framework for functional molecular connectivity, emphasizing the importance of carbon–heteroatom linkages in joining modular building blocks.11 A click reaction must be modular, wide in scope, give very high yields, generate only inoffensive byproducts that can be removed by non-chromatographic methods, and be stereospecific.11 The incorporation of click chemistry-based design elements has led to recent advances towards novel functional IL systems.12,13

Although electrochemical approaches were used to effectively synthesize sulfonyl fluorides,14–17 the applications or possible uses of these compounds in energy are limited. In 2019, Xue et al. developed “full fluorosulfonyl” electrolyte for 4 V class of lithium-metal batteries via imitating of organic solvent ethylsulfamoyl fluoride (FSO2–NEt2) with lithium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide (LiFSI).1 This new electrolyte is compatible with both the Li metal anode and the metal-oxide cathode, which is crucial for high-voltage rechargeable lithium-metal batteries. This electrolyte outperforms the well-known traditional ether/carbonate-based electrolyte and has the highest coulombic efficiency (CE) ever reported for non-ether-based electrolytes. The electrolyte enabled a highly reversible Li metal anode (LMA) with an excellent initial CE of 91%, which rapidly approached 99% within only 10 cycles. This electrolyte shows excellent Li compatibility and does not require high salt concentration to achieve highly reversible Li plating/stripping, thus avoiding high viscosity, poor wettability, and high cost. It was reported that this electrolyte enables a highly reversible LMA, outperforming well-known fluoroethylene carbonate-based electrolyte.

In addition, as reported by Shkrob et al., the IL electrolyte systems containing FSI anion show promise as electrolytes for Li-ion-based electric storage devices.18 They display relatively low viscosity, high chemical stability, and create a sturdy solid–electrolyte interphase (SEI), preventing liquid electrolyte from further breakdown on the electrode. Additionally, the FSI anion inhibits dendrite formation on the lithium metal and lithiated graphite electrodes, which is attributed to its unique SEI properties. The FSI anion appears to perform differently from many other anions (e.g., NTf2−) in IL electrolyte systems. Various lines of evidence suggest that the chemical properties of the FSI anion are responsible for this difference.

To address these issues, we recently developed a series of thermally stable and chemically robust ILs with a SO2F moiety (Fig. 1) via an exceptionally facile and efficient fluorosulfonylethylation synthetic procedure.2 The uniqueness of the SO2F motif, both in its properties and potential applications as well as its dissimilarity to other common structural IL components, made it a fascinating point of interest for further studies. The diversification of the sulfonyl fluoride ILs has been extended to include active pharmaceutical precursors with established toxicity profiles, allowing access to functional materials with a priori low toxicity (Fig. 1). Given the established biocompatibility of sulfonyl fluoride motifs, the preparation of ILs of this type that also incorporate APIs is expected to demonstrate reduced toxicity. Additionally, in order to aid defining their practical range of use for various utilities, we employed a combination of thermophysical analyses, computational modeling, and X-ray crystallographic studies to obtain a rigorous understanding of their structure-property relationships. The SO2F motif provides high electronegativity, which allows increased anodic stability. SO2F-bearing ILs may exhibit high ionic conductivity due to their high charge density. We hypothesized that the presence of the sulfonyl fluoride moiety also contributes to a more favorable solvation of lithium ions, which can lead to better performance in lithium-metal batteries. Therefore, the combination of the unique properties of ILs and the favorable characteristics of sulfonyl fluoride-containing ILs make them promising candidates as electrolytes in the lithium batteries.

Figure 1.

Structures of synthesized SO2F-based ILs, paired with NTf2− anion (that are omitted for clarity) along with their Tm/Tg values. No Tm/Tg values were detected for 10. The data is reported in our previous work.2

Encouraged by these results, we decided to seek greater insight into the structures of sulfonyl fluoride ionic liquids via structural studies. Therefore, we performed X-ray crystallographic analysis to gain deeper insight into the spatial relationships between the cations and anions, enhancing the understanding of their physicochemical properties. However, because of the conformational freedom of the Tf2N− anion, ILs with this anion show complex crystallization behavior, and growing diffraction-quality crystals is quite difficult. Therefore, we prepared two sulfonyl fluoride salts paired with hexafluorophosphate (PF6−) anion, which were single-crystalline at room temperature for X-ray studies. The salts, 2-PF6 and 5-PF6 were thoroughly investigated via X-ray diffraction, as shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Asymmetric units of 5-PF6 (left) and 2-PF6 (right). Disorder omitted for clarity.

The crystal structure of materials can provide a wealth of information in addition to simple geometric parameters. For example, the Bernasconi group used powder X-ray diffraction to explain the ionic transport properties of ionic solids via temperature-dependent diffraction studies.19 Specifically, the anion transport properties of molybdenum complexes were studied by evaluating the geometric changes in the coordination of distinct moieties within the solid-state structures. Furthermore, ILs were examined by crystallographic studies to explain their transport properties, which provides insight into the potential development of solid-state electrolytes.20 However, key to these studies is the necessity to understand how the cations and anions interact. Thus, with the inclusion of the novel −SO2F functional group, a systematic evaluation of the interionic interactions within these compounds is of key importance for the development of functional materials.

Hexafluorophosphate anion (PF6−) has long been used as a fluorinated spectator anion due to its small size, non-nucleophilicity, non-basicity, poorly coordinating, and chemical and thermal stability. As a consequence, PF6− has found widespread utilities in several contexts: as an anion to form ILs, diamondoid nanoporous crystals21 and rechargeable batteries.22 Its weak coordinating affinity means that it is less likely to compete for active sites on metal-based catalysts. In addition, ILs with PF6− tend to have strong hydrophobic character, which is indispensable in situations where the IL is to be used in aqueous biphasic catalysis or in aqueous extractions. Finally, this anion is among the most thermally stable anions known.23

Materials and Methods

Materials and instrumentation.—

All commercial chemicals were used as received, unless otherwise noted. Extra dry solvents over molecular sieves were purchased from Acros Organics. 1H, 13C, 31P, and 19F NMR were performed on a JEOL 400 MHz NMR at 295 K. Chemical shifts (δ) are quoted in parts per million (ppm) and referenced to the appropriate NMR solvent residual peaks. The melting points and glass transition temperatures were measured using a TA Discovery 250 differential scanning calorimeter calibrated using indium (melting point) and sapphire (heat capacity) references with a heating and subsequent cooling rate of 5 °C min−1. Thermogravimetric analyses were performed on a TA instrument, TGA Q500, under nitrogen flow using an aluminum pan. The samples were heated at the rate of 2 °C min.

General synthesis procedure.—

Synthetic procedures were reported in our previous work.2 Briefly, the synthesized 2-chloroethanesulfonyl fluoride was reacted with the desired heterocyclic headgroups, that is 1,2-dimethylimidazole and 1-methyl-1,2,4-triazole to form sulfonyl fluoride salts. The headgroup and 2-chloroethanesulfonyl fluoride were separately dissolved in ethyl acetate and combined in one portion. Precipitation was observed immediately. The reaction was allowed to proceed to run for 2 h to reach completion. The precipitation was vacuum filtered and was washed three times with EtOAc. Afterwards, 1.1 equiv. of KNTf2 or NaPF6 was reacted with the synthesized sulfonyl fluoride-based halide salts. They were separately dissolved in deionized water and mixed in one portion. The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 8 h to obtain two distinct phases. The lower layer was separated and washed three times with deionized H2O. It was then dried by heating in vacuo for 8 h at 50 °C, yielding IL products in quantitative yields. 1H, 13C, 31P, and 19F NMR analyses were performed to confirm purity.

2-PF6.— 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δH 7.60 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 3.30 (t, J = 1.6 Hz, 2H), 4.82 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 4.67 (q, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 3.85 (s, 3H). 19F NMR (376 MHz, CD3OD) δ −75.9; −80.6; 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δC 124.0, 122.7, 121.6, 118.2, 115.0, 49.5, 49.0, 35.5, 9.8. 31P NMR (162 MHz, CD3OD) δP −130.9, −135.3, −139.6, −144.0, −148.4, −152.8, −157.2.

5-PF6.— 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δH 9.02 (s, 1H), 4.93 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 4.41 (q, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 4.16 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CD3OD) δC 146.0, 144.9, 50.2, 50.0, 49.0, 43.1, 39.6; 19F NMR (376 MHz, CD3OD) δF −73.5, −75.4; 31P NMR (162 MHz, CD3OD) δP −130.9, −135.3, −139.6, −144.0, −148.4, −152.8, −157.2.

Single crystal diffraction.—

Single crystals of compound 2-PF6 and 5-PF6 were coated with Parabar 10312 oil and transferred to the goniometer of a Bruker D8 Quest Eco diffractometer with Mo Kα wavelength (λ = 0.71073 Å) and a Photon II area detector. Examination and data collection were performed at 150 °K for 5-PF6 and at 100 °K for 2-PF6. Data were collected, reflections were indexed and processed, and the files scaled and corrected for absorption using APEX324 and SADABS.25 For all compounds, the space groups were assigned using XPREP within the SHELXTL suite of programs,26,27 the structures were solved by direct methods using ShelXS or ShelXT28 and refined by full matrix least squares against F2 with all reflections using Shelxl201829 using the graphical interfaces Shelxle30 and/or Olex2.31 H atoms were positioned geometrically and constrained to ride on their parent atoms. C–H bond distances were constrained to 0.95 Å for aromatic and alkene C-H moieties, and to 0.99 and 0.98 Å for aliphatic CH2 and CH3 moieties, respectively. Methyl H atoms were allowed to rotate, but not to tip, to best fit the experimental electron density. Uiso(H) values were set to a multiple of Ueq(C) with 1.5 for CH3 and 1.2 for C–H and CH2 units, respectively. For 5-PF6, the PF6− anion is rotationally disordered over three positions with occupancy ratios of 0.3973, 0.3365, and 0.2661. The anions were restrained to have similar geometries.

Complete crystallographic data in CIF format were deposited on the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre. CCDC 2258605 and 2258606 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this study. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Software.—

Hirshfeld surfaces, images, and fingerprint plots were calculated and produced using CrystalExplorer21.32 Images and analysis of the structures was accomplished using Olex2 and Mercury.33 All parts of the disorder were included in the structural analysis of the compounds. For all images shown in the crystal structures the following color scheme was used to represent atoms: carbon = gray, nitrogen = blue, hydrogen = white, fluorine = green, oxygen = red, and sulfur = yellow. Thermal ellipsoids are shown at 50% probability.

All computations and the resultant data were obtained using the Spartan software suite (Spartan’20, Wavefunction, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA). The initial geometries of the cations for compounds 2-PF6 and 5-PF6 were loaded into the software and optimized using the M06–2X methods34 with a 6–311++G(d,p) basis set. The optimization was performed using a simulated water solution. After the structure was optimized, a final single-point energy calculation was performed using M06–2X methods with a 6–311+G(2df,2p) basis set. The vibrational frequencies were checked for imaginary values to ensure that the resultant structures were at a minimum.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis.—

We previously reported the synthesis of ILs 1–11, which follows a three-step procedure (Scheme 1).2 The first is the preparation of 2-chloroethanesulfonyl fluoride using the sulfonyl chloride−fluoride exchange using a saturated K(FHF) solution. The second step involves the Menshutkin reaction between 2-chloroethanesulfonyl fluoride and the heterocyclic headgroups. The third part is the anion metathesis of the chloride anion in the product with the NTf2− anion by reaction with an aqueous KNTf2 solution. For the preparation of 2-PF6 and 5-PF6, the salt metathesis reaction was performed in an aqueous solution of NaPF6.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic pathway of the IL 1 as a representative method for the synthesis of sulfonyl fluoride-bearing ILs.2

Remarkably, purification was seldom necessary during each step of the process and the resulting IL products were obtained using straightforward filtration techniques. It was observed that the IL products were soluble in H2O and MeOH, but insoluble in EtOAc, which served as an effective medium for purifying the ILs from their precursors. The yields for both the intermediate chloride salts and the final NTf2/PF6 IL products were quantitative. As expected, these ILs exhibited robust chemical stability towards hydrolysis and thermolysis, thus rendering them dependable materials suitable for a wide range of environmental conditions. With an easy procedure to follow, coupled with readily accessible starting materials, it is possible to synthesize multigram quantities of these ILs; e.g., up to 20 g. Active pharmaceutical precursors were employed as headgroups to create SO2F–IL systems with a priori low toxicity. In turn, we selected nitroimidazoles and 4-aminopyridine as the core for ILs 3, 4, 11. Nitroimidazoles are the backbone of several antimicrobial compounds35 and aminopyridine forms the core for dalfampridine which is used for the treatment of multiple sclerosis.36

Crystal and molecular structures.—

Two compounds bearing ethylsulfonyl fluoride side-chain were synthesized and crystallized. The PF6− anion was chosen both for its importance in the field of electrochemistry37–39 as well as to expand upon our previously reported synthesis of the NTf2 based compounds.40 Two distinct heterocycles were used for these compounds. First, 1,2-dimethylimidazole was chosen to supplement our previously reported structural and crystallographic analyses of the NTf2-based congener. With the synthesis and evaluation of the PF6− structure, the direct comparison of the two compounds presented herein provides excellent insight into what structural changes are imparted by the switch from the larger NTf2 anion to a smaller, more spherical PF6−. Second, 1-methyl-1,2,4-triazole was chosen given our group’s interest in the study of non-imidazolium based ILs.41,42 The inclusion of an additional heterocyclic nitrogen in the ring, when compared with imidazolium heterocycles, has an impact on both the intermolecular interactions of the cation and on the electronics of the system.

Molecular conformations.—

Both compounds 2-PF6 and 5-PF6 crystallize in a monoclinic P21/n crystal system with a single cation-anion pair in the asymmetric unit. Aside from the rotational disorder in 5-PF6, the PF6− anions in both compounds show no notable deviations from the expected bond angles and distances from previously reported structures.33 The cation geometry for both structures are very similar, with both showing nearly identical bond angles and distances (Fig. 2). For both structures, the ethylsulfonyl fluoride chain exists in the G conformation43 with an N1—C7—C8—S1 torsion angle of 74.80(6)° and 76.87(9)° for 2-PF6 and 5-PF6, respectively. This conformation is distinct from that observed in previously reported structures, which all existed in the T conformation with torsion angles ≈ 180°. Specifically, compound 2 showed a torsion angle of 164.3(3)°.

The torsion angles of the −SO2F moiety are also distinct when comparing the series of molecules. Table I summarizes the bond distances and torsion angles for all currently reported structures of ILs bearing ethylsulfonyl fluoride side chains. No unexpected conformations were observed for the group with most of the torsion falling within the range of ± 60–80°. The variation in torsion angles is attributed to the interactions arising from the −SO2F motif, as indicated in our previous study.44 Specifically, the sulfonyl oxygen atoms tend to form shorter interactions with neighboring groups, with interactions being dominant.

Table I.

List of geometric values for the cations of ionic liquids bearing the ethanesulfonyl fluoride alkyl chain taken from their crystal structures.

| ϕ1 | ϕ2 | C7—S1 | S1—O1 | S1—O2 | S1—F1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 2-PF6 | 76.87 | 73.40 | 1.763 | 1.418 | 1.419 | 1.559 |

| 2-PF6 OPTa) | 66.16 | 58.21 | 1.780 | 1.436 | 1.435 | 1.610 |

| 5-PF6 | 74.80 | 62.21 | 1.768 | 1.420 | 1.410 | 1.563 |

| 5-PF6 OPTa) | 72.24 | 66.68 | 1.780 | 1.437 | 1.433 | 1.607 |

| 2-NTf2 | 164.28 | −59.60 | 1.755 | 1.413 | 1.410 | 1.560 |

| Mim BETI | 169.22 | −64.46 | 1.754 | 1.432 | 1.409 | 1.526 |

| 5-NO2 | 172.37 | −57.22 | 1.759 | 1.412 | 1.460 | 1.494 |

| Pyridine A | 166.66 | 54.40 | 1.766 | 1.407 | 1.434 | 1.509 |

| Pyridine B | 176.76 | −77.93 | 1.764 | 1.411 | 1.404 | 1.539 |

| Pyridine C | 169.52 | 55.71 | 1.751 | 1.429 | 1.414 | 1.523 |

| Pyridine D | 175.48 | −80.01 | 1.726 | 1.402 | 1.425 | 1.532 |

values taken from the computationally optimized structures.

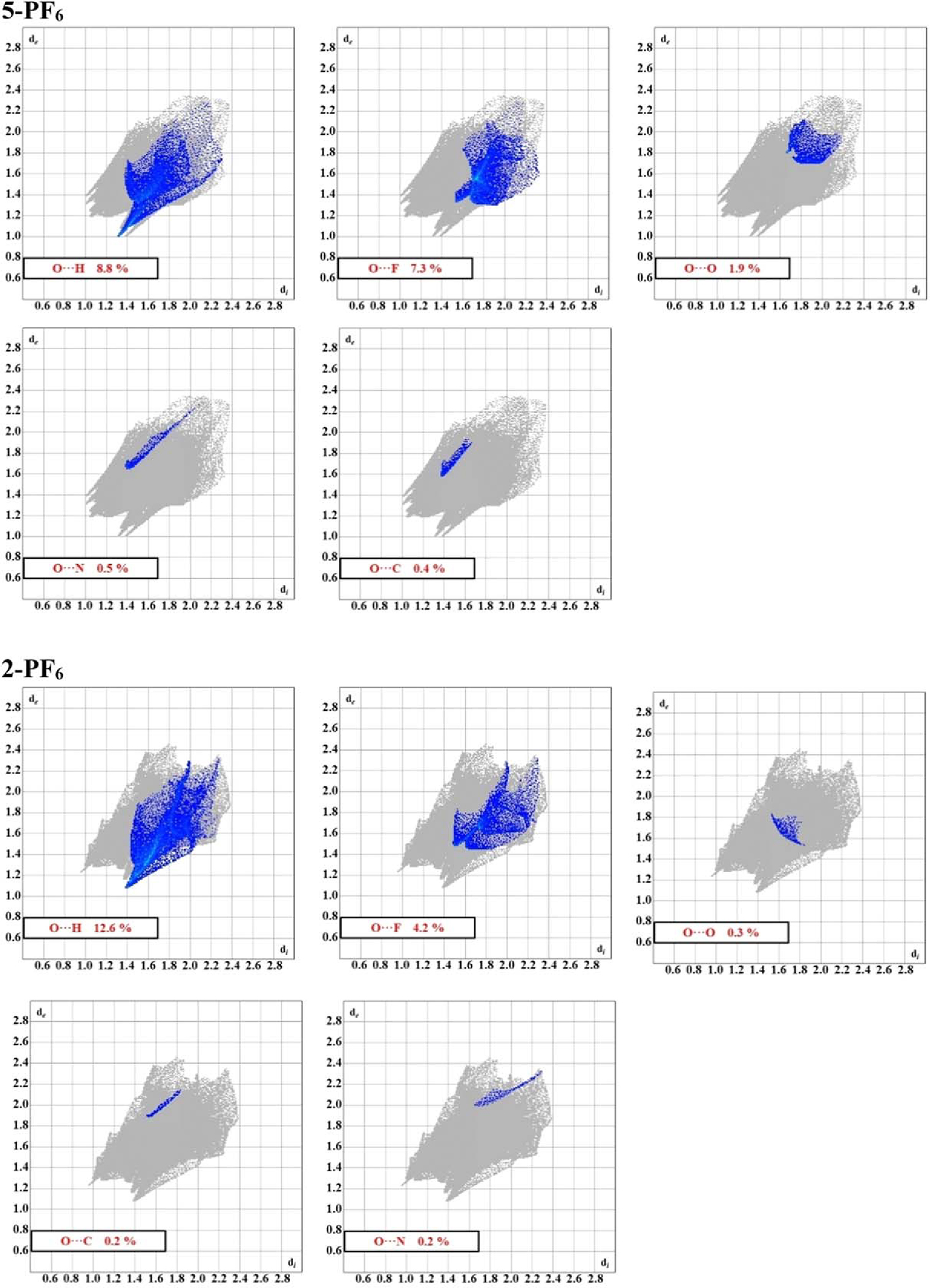

Hirshfeld surface analysis and interactions.—

To better understand the molecular and solid-state structures of these compounds, Hirshfeld surface analysis was performed on both the crystals. For 5-PF6, all parts of the disordered anion were used in the calculations. The calculated Hirshfeld surface mapped with the dnorm and shape index functions are shown in Fig. 3. The interaction fingerprints for 2-PF6 and 5-PF6 are shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 3.

The Hirshfeld surface mapped with the dnorm (left) and the shape index (right) for 2-PF6 and 5-PF6.

Figure 4.

The complete interaction fingerprints for 5-PF6 (left) and 2-PF6 (right).

Several important observations can be drawn when examining the fingerprints of compounds. For example, spikes are seen in the lower, left portion of the interaction fingerprints. These spikes correspond to interactions arising between hydrogen atoms with different moieties in the crystals. The individual hydrogen fingerprint plots are shown in Fig. 5. There are clear differences in the H-interactions when contrasting the two cations naturally arising from the different elemental compositions of the compounds. Contrasting the individual H-interactions points to several clear distinctions when contrasting the PF6− based compounds. As anticipated, the H···F | F···H interactions comprise the largest percentage of interactions for both molecules. However, a distinction should be made for the F atoms on the anion vs the cation, particularly with concern to the interactions arising from the FSO2F moiety, which will be the focus of the analysis herein.

Figure 5.

The hydrogen interaction fingerprints for 2-PF6 (top) and 2-PF6 (bottom).

Cation-fluorine interactions.—

Figure 6 displays the interactions arising from the FSO2F for both 2-PF6 and 5-PF6. Several notable distinctions can be observed when examining the interactions of the atom. For both compounds, the fluorine atom interacts with the H, C, N, O, and F atoms. In general, the nature of H…F interactions is rather complex, and dependent on steric and electronic factors.45,46 For both 2-PF6 and 5-PF6, the distances and angles of these interactions herein fall within the expected ranges of previously reported, stabilizing H···F interactions.47 Specifically, for 5-PF6, a set of reciprocal F···H | H···F interactions link two cations in a dimer-like arrangement in the crystal structure (Fig. 7). The moiety is interacting with both an aromatic H and a methylene H in the ethyl side chain of the cation, with the shortest distances being 2.5064(8) Å and 2.7883(7) Å .

Figure 6.

Interaction fingerprints arising from the F atom on the −SO2F moiety on the 5-PF6 (top row) and 2-PF6 (bottom row).

Figure 7.

RSO2F…H interactions for 5-PF6 (top) and 2-PF6 (bottom). Interactions shown as blue dotted lines and set to a maximum cutoff of van der Waal radii + 0.3 Å.

For 2-PF6, however, the H···F interactions form a chain of cations instead of the dimer arrangement in 5-PF6. In 2-PF6, the fluorine atom is interacting with only the methyl hydrogens on the adjacent cation, and not the aromatic hydrogens. The distances range from 2.60–3.30 Å . Longer interactions with symmetrical adjacent methylene units are also present; however, with a distance near 3.80 Å this interaction is likely an artifact of the crystal packing.

While the H···F interactions are likely a stabilizing set of interactions within these crystals, the also interacts with the O and F atoms in both compounds, likely forming destabilizing interactions. Here, again, we see both similarities and differences between the two compounds. Similarities arise when examining the interactions with the oxygen atoms (Fig. 8). Two symmetry-related −SO2F moieties form a reciprocal set of F···O | O···F interactions. The F···O distances are similar with distances of 3.2760(11) Å for 5-PF6 and 2.9954(11) Å for 2-PF6 (d(F1···O2i)). Notably, the distances are shorter for 2-PF6 than 5-PF6. This is observed in the shape of fingerprint wherein the interaction regions associated with the O···F interactions terminate at different distances (Fig. 6).

Figure 8.

Depiction of the F…O interactions in 5-PF6 (top) and 2-PF6 (bottom) Interactions are depicted in blue. A cutoff for interactions was set at the van der Waal radius of fluorine + 0.3 Å.

The F···F interactions in 5-PF6 and 2-PF6 present a point of distinction between the cations with respect to the interactions arising from the −SO2F moiety (Fig. 9). For 2-PF6, the interactions exist only between the cation and anion, wherein various fluorine atoms on the PF6− anion form a chain of interacting cations and anions with F···F distances of 3.0785(9) Å (d(F1···F5k, k = 1−x, +y, +z) and 3.3902(9) Å (d(F1···F7l, l = −½+x, ½−y, ½+z). While 5-PF6 also shows contacts between the cation and anion, there are also close contacts with a symmetry-adjacent cation. The distance is 2.9357(15) Å (d(F1···F1i, i = −x, 1−y, 1−z). These F···F contacts arise as a consequence of the H···F interactions discussed previously (vide supra). Thus, we speculate that the F···F interactions in 5-PF6 are merely a consequence of packing to maximize other interactions rather than some stabilizing effect due to the presence of any σ-hole interactions.48

Figure 9.

Depiction of the F…F interactions in 5-PF6 (top) and 2-PF6 (bottom). Interactions are depicted in blue. A cutoff for interactions was set at the van der Waal radius of fluorine + 0.5 Å.

To summarize, the fluorine moiety in the −SO2F functional group on the cations is observed to interact with a range of symmetrally adjacent moieties. The atom forms a number of cation-cation and cation-anion interactions. For example, both 5-PF6 and 2-PF6 display short interactions, likely forming a series of stabilizing interactions. The geometric arrangement of these interactions is different for both molecules, with 5-PF6 forming a dimer-like arrangement linked through these F···H interactions, while 2-PF6 forms a chain-like motif. For both molecules; however, the formation of these interactions also gives rise to a set of intercationic F···F interactions.

Oxygen interactions.—

For both compounds, the oxygen atoms in the −SO2F moiety (i.e.,) introduces multiple cation-cation interactions. The fingerprint plots in Fig. 10 show the specific interactions with the H, N, and C atoms. Several key details emerge when examining the interaction fingerprints. First, H···O interactions are the most abundant, by percentage, for both compounds. The oxygen atoms in both compounds are interacting with both the alkyl and aryl hydrogens (see Fig. S1). Second, the C···O and N···O interactions arise from interactions with the system of the heterocycle. Specifically, we observe the interactions from the electronegative with the regions of the heterocycle associated with the delocalized positive charge in the system of the ring, between the two alkylated nitrogen atoms.49 Finally, the moieties form a number of repulsive interactions with both O and F atoms. While interactions were discussed previously (vide supra), we also observe a number of interactions as well for both compounds. These interactions range from approximately 3.10–3.42 Å for 2-PF6 and 2.88–3.41 Å for 5-PF6 (d(O···F)). The similarities in the interactions, both with respect to distances and angles, are reflected in the fingerprints for the O···F interactions. The notably higher percentage of interactions for 5-PF6 is attributed to the disordered anion.

Figure 10.

The oxygen interaction fingerprints for 5-PF6 (top) and 2-PF6 (bottom).

With respect to the O···O interactions, there is a clear distinction observed in the fingerprint for both compounds. In 5-PF6, both atoms form a reciprocal set of interactions with an O···O distance of 3.4900 (13) Å (d(O2···O1m, m = 1−x, 1−y, 1−z). In 2-PF6, however, the calculated O···O contacts arise from the arrangement of the O···F interactions, which were discussed previously, thus giving rise to the disperse shape of the fingerprint (see Fig. 10). As with the F···F interactions, we conclude that these O···O interactions are a consequence of packing to maximize the expected stabilizing interactions (i.e. H···O, C···O, N···O). However, it should be noted that in specific cases, these O···O interactions can be considered as bonds.50 A thorough and comprehensive computational investigation focusing on the specifics of the −SO2F moieties would help clarify these lingering questions.

In summary, several key details can be drawn out when examining the interactions within these systems. First, the oxygen atoms in the −SO2F moiety interact with hydrogen atoms and the π system of the cationic heterocycles. For both compounds, the atoms introduce a significant percentage of cation-cation interactions. At the same time, the −SO2F moiety also exhibits O···F interactions which are predominantly, though not exclusively, with the anion fluorine atoms . Thus, sulfonyl fluorides introduce a complex set of stabilizing and destabilizing interactions.

Second, concerning the interactions arising from the −SO2F moiety, both stabilizing interactions (H···F) and destabilizing interactions (F···O and F···F) were observed. While these interactions vary in distances and geometry, they arise from combinations of cation-cation and cation-anion interactions. Despite the subtle differences in the interaction geometries, as systematic crystallographic studies of −SO2F groups continue, certain interaction synthons have begun to emerge. Further evaluation of this functional group is warranted to help establish these synthons and to help establish the nature of these interactions (i.e., stabilizing vs. destabilizing).

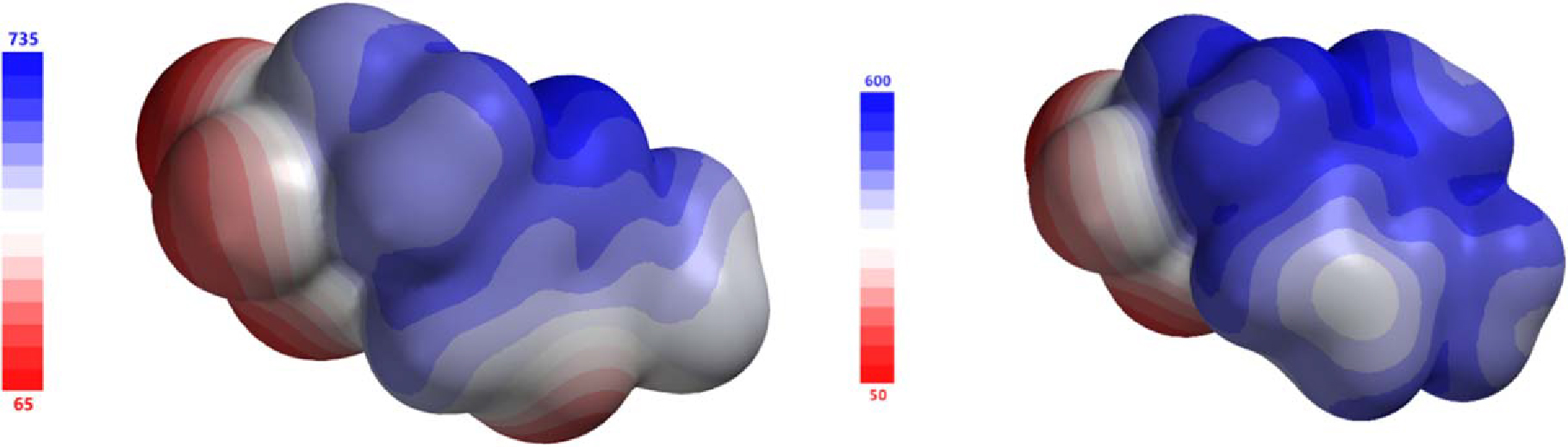

Computational analysis.—

To better understand the interactions observed in the solid-state, the molecular structures of 5-PF6 and 2-PF6 cations from the asymmetric unit were optimized and the electrostatic potential (ESP) was calculated (Figure 11).51 The ESP has been shown to provide valuable insight into the packing and interactions in molecules.52 Furthermore, the atomic charges and molecular orbitals of the compounds were also calculated to allow for a thorough understanding of the impacts of the sulfonyl fluoride group for the cation. The theoretical data provide several insights.

Figure 11.

The electrostatic potential mapped on the molecular surface of 5-PF6 (left) and 2-PF6 (right). Red indicated negative potential. Blue is positive potential.

First, the heterocycles in both compounds display the expected delocalized positive charge, as has been examined thoroughly in the literature.49 Notably, in 5-PF6, N2 has a negative charge, which is observed in the crystal wherein N2 interacts with nearby hydrogen atoms, introducing additional cation-cation interactions. Second, the oxygen atoms on the −SO2F moiety are observed to have a more negative Mullikan charge53 when compared with the fluorine atom. This has been observed in our previous studies as well.44 Finally, the HOMO and LUMO of the cations were calculated and are shown in Fig. 12. For both sets of orbitals, we see that π-type orbitals on the rings comprise the majority of the density within these systems, which is in line with previously reported studies.54 Thus, in conjunction with previous data, we see that the −SO2F moiety appears to have little influence on the electronic structure of the cation. However, the inclusion of a −SO2F group has a significant impact on the intermolecular interactions.

Figure 12.

The calculated highest occupied and lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals for the cations in 5-PF6 (top) and 2-PF6 (bottom).

Conclusions

This endeavor represents the introduction of a sulfonyl fluoride moiety into IL structures as a biologically compatible model for developing functional ILs with a priori reduced toxicity. Through a facile approach, we developed a wide variety of ionic materials bearing the pharmaceutically significant sulfonyl fluoride moiety and characterized several notable trends in thier physicochemical properties to inform and expand the understanding of IL design principles. The sulfonyl fluorides are considerably more thermodynamically stable than other sulfonyl halides toward hydrolysis, reduction, and thermolysis. In this work, two structurally diverse IL-SO2F systems with PF6− anion as hydrophobic, non-coordinating anion were synthesized, and further insight on their structure-property relationships were provided through SC–XRD data paired with Hirshfeld surface analysis. That is, examining the library of reported IL-type compounds bearing the ethylsulfonyl fluoride motif reveals information about the conformational flexibility of this side chain. Specifically, we observed two distinct conformations arising from the gauche and anti arrangements of the chains. Of note is that the gauche conformation is only observed with the PF6− anion while the NTf2− anion displays the anti in the solid-state. A systematic crystallographic study involving the prototypical anions used for ILs synthesis55 would help clarify these observations.

Finally, while our findings focused on the structure-property elucidation of SO2F-IL systems, structurally similar ILs can be tuned for effective electrolyte systems for energy storage devices, particularly LMBs. This work is laying the foundations to design “better” electrolytes for the thorough elucidation of fundamental design considerations. Further experiments are underway to electrochemical characterization of these functional ILs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work is provided by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), the NIH, under Award R21GM142011. Acknowledgment is made by P.C.H. to the Donors of the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund (66195-UNI10) for partial support of this research. C.A. and A.M. are grateful to the Richard S. Shineman Foundation and Oswego College Foundation for the generous financial support. M.B. and P. C.H. would like to thank Michael and Lisa Schwartz, and Joe and Karen Townshend for their generous financial supports for the undergraduate research program and purchasing of research instrumentation in the Department of Chemistry and Physics at AMU. We sincerely acknowledge the valuable feedback provided by the anonymous reviewers for this work.

Footnotes

Supplementary material for this article is available online

References

- 1.Xue W et al. , “FSI-inspired solvent and ‘full fluorosulfonyl’ electrolyte for 4 V class lithium-metal batteries.” Energy Environ. Sci, 13, 212 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel DJ, Anderson GI, Cyr N, Lambrecht DS, Zeller M, Hillesheim PC, and Mirjafari A, “Molecular design principles of ionic liquids with a sulfonyl fluoride moiety.” New J. Chem, 45, 2443 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Narayanan A and Jones LH, “Sulfonyl fluorides as privileged warheads in chemical biology.” Chem. Sci, 6, 2650 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones LH and Kelly JW, “Structure-based design and analysis of sufex chemical probes.” RSC Med. Chem, 11, 10 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dong J, Krasnova L, Finn MG, and Sharpless KB, “Sulfur(VI) fluoride exchange (SuFEx): another good reaction for click chemistry.” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 53, 9430 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrow AS, Smedley CJ, Zheng Q, Li S, Dong J, and Moses JE, “The growing applications of SuFEx click chemistry.” Chem. Soc. Rev, 48, 4731 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinkopf W, “Über aromatische sulfofluoride.” J. Für Prakt. Chem, 117, 1 (1927). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toulgoat F, Langlois, Bernard R, Médebielle M, and Sanchez J-Y, “An efficient preparation of new sulfonyl fluorides and lithium sulfonates.” J. Org. Chem, 72, 9046 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiochan P, Yu X, Sawangphruk M, and Manthiram A, “A metal organic framework derived solid electrolyte for lithium–sulfur batteries.” Adv. Energy Mater, 10, 2001285 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paillard E, Toulgoat F, Sanchez J-Y, Médebielle M, Iojoiu C, Alloin F, and Langlois B, “Electrochemical investigation of polymer electrolytes based on lithium 2-(Phenylsulfanyl)−1,1,2,2-tetrafluoro-ethansulfonate.” Electrochim. Acta, 53, 1439 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolb HC, Finn MG, and Sharpless KB, “Click chemistry: diverse chemical function from a few good reactions.” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 40, 2004 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirjafari A, “Ionic liquid syntheses via click chemistry: expeditious routes toward versatile functional materials.” Chem. Commun, 54, 2944 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirjafari A, O’Brien RA, West KN, and Davis JH, “Synthesis of new lipid-inspired ionic liquids by thiol-ene chemistry: profound solvent effect on reaction pathway.” Chem.—Eur. J., 20, 7576 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen D, Nie X, Feng Q, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang Q, Huang L, Huang S, and Liao S, “Electrochemical oxo-fluorosulfonylation of alkynes under air: facile access to β-keto sulfonyl fluorides.” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed, 60, 27271 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park JK, Oh J, and Lee S, “Electrochemical synthesis of sulfonyl fluorides from sulfonyl hydrazides.” Org. Chem. Front, 9, 3407 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L, Cheng X, and Zhou Q-L, “Electrochemical synthesis of sulfonyl fluorides with triethylamine hydrofluoride.” Chin. J. Chem, 40, 1687 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng Q, Fu Y, Zheng Y, Liao S, and Huang S, “Electrochemical synthesis of β-keto sulfonyl fluorides via radical fluorosulfonylation of vinyl triflates.” Org. Lett, 24, 3702 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shkrob IA, Marin TW, Zhu Y, and Abraham DP, “Why Bis(Fluorosulfonyl) Imide is a ‘magic anion’ for electrochemistry.” J. Phys. Chem. C, 118, 19661 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernasconi A, Tealdi C, and Malavasi L, “High-temperature structural evolution in the Ba3 Mo(1–x) Wx NbO8.5 system and correlation with ionic transport properties.” Inorg. Chem, 57, 6746 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDaniel JG and Yethiraj A, “Grotthuss transport of iodide in EMIM/I3 ionic crystal.” J. Phys. Chem. B, 122, 250 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Białek MJ and Klajn R, “Diamond grows up.” Chem, 5, 2283 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xue Z, Gao Z, and Zhao X, “Halogen storage electrode materials for rechargeable batteries.” ENERGY Environ. Mater, 5, 1155 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maton C, Vos ND, and Stevens CV, “Ionic liquid thermal stabilities: decomposition mechanisms and analysis tools.” Chem. Soc. Rev, 42, 5963 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruker (2019) Apex3 V.1–0SAINT V8.40A. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krause L, Herbst-Irmer R, Sheldrick GM, and Stalke D, “Comparison of silver and molybdenum microfocus X-ray sources for single-crystal structure determination.” J. Appl. Crystallogr, 48, 3 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.SHELXTL Suite of Programs, Version 6.14, 2000–2003, Bruker Advanced X-ray Solutions. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheldrick GM, “A short history of SHELX.” Acta Crystallogr. A, 64, 112 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheldrick GM, “SHELXT—integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination.” Acta Crystallogr. Sect. Found. Adv, 71, 3 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheldrick GM, “Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL.” . Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem, 71, 3 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hübschle CB, Sheldrick GM, and Dittrich B, “ShelXle : A Qt graphical user interface for SHELXL.” J. Appl. Crystallogr, 44, 1281 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dolomanov OV, Bourhis LJ, Gildea RJ, Howard JAK, and Puschmann H, “OLEX2 : A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program.” J. Appl. Crystallogr, 42, 339 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spackman PR, Turner MJ, McKinnon JJ, Wolff SK, Grimwood DJ, Jayatilaka D, and Spackman MA, “CrystalExplorer : a program for hirshfeld surface analysis, visualization and quantitative analysis of molecular crystals.” J. Appl. Crystallogr, 54, 1006 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macrae CF, Bruno IJ, Chisholm JA, Edgington PR, McCabe P, Pidcock E, Rodriguez-Monge L, Taylor R, van de Streek J, and Wood PA, “Mercury CSD 2.0—new features for the visualization and investigation of crystal structures.” J. Appl. Crystallogr, 41, 466 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao Y and Truhlar DG, “The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals.” Theor. Chem. Acc, 120, 215 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyamoto Y et al. , “Expanded therapeutic potential in activity space of next-generation 5-nitroimidazole antimicrobials with broad structural diversity.” Proc. Natl Acad. Sci, 110, 17564 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sedehizadeh S, Keogh M, and Maddison P, “The use of aminopyridines in neurological disorders.” Clin. Neuropharmacol, 35, 191 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valøen LO and Reimers JN, “Transport properties of LiPF[Sub 6]-based Li-Ion battery electrolytes.” J. Electrochem. Soc, 152, A882 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seel J and Dahn J, “Electrochemical intercalation of PF6 into graphite.” J. Electrochem. Soc, 147, 892 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nanjundiah C, Goldman JL, Dominey LA, and Koch VR, “Electrochemical Stability of LiMF6 ( M = P, As, Sb ) in Tetrahydrofuran and Sulfolane.” J. Electrochem. Soc, 135, 2914 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siegel DJ et al. , “Design principles of lipid-like ionic liquids for gene delivery.” ACS Appl. Bio Mater, 4, 4737 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castillo C, Chenard E, Zeller M, Hatab N, Fulvio PF, and Hillesheim PC, “Examining the structure and intermolecular forces of thiazolium-based ionic liquids.” J. Mol. Liq, 327, 114800 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hillesheim PC, Mahurin SM, Fulvio PF, Yeary JS, Oyola Y, Jiang D, and Sheng D, “Synthesis and characterization of thiazolium-based room temperature ionic liquids for gas separations.” Ind. Eng. Chem. Res, 51, 11530 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saouane S, Norman SE, Hardacre C, and Fabbiani FPA, “Pinning down the solid-state polymorphism of the ionic liquid [Bmim][PF6].” Chem. Sci, 4, 1270 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bellia S, Teodoro LI, Barbosa AJ, Zeller M, Mirjafari A, and Hillesheim PC, “Contrasting the noncovalent interactions of aromatic sulfonyl fluoride and sulfonyl chloride motifs via crystallography and hirshfeld surfaces.” ChemistrySelect, 7, e202203797 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.D’Oria E and Novoa JJ, “On the hydrogen bond nature of the C–H⋯F interactions in molecular crystals. an exhaustive investigation combining a crystallographic database search and ab initio theoretical calculations.” CrystEngComm, 10, 423 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dunitz JD, “Organic fluorine: odd man out.” ChemBioChem, 5, 614 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wood PA, Allen FH, and Pidcock E, “Hydrogen-bond directionality at the donor h atom—analysis of interaction energies and database statistics.” CrystEngComm, 11, 1563 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Politzer P, Murray JS, and Clark T, “Halogen bonding and other σ-hole interactions: a perspective.” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 15, 11178 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hunt PA, Kirchner B, and Welton T, “Characterising the electronic structure of ionic liquids: an examination of the 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ion pair.” Chem. Eur. J, 12, 6762 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhurova EA, Tsirelson VG, Stash AI, and Pinkerton AA, “Characterizing the oxygen−oxygen interaction in the dinitramide anion.” J. Am. Chem. Soc, 124, 4574 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murray JS and Politzer P, “The electrostatic potential: an overview.” WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci, 1, 153 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spackman MA, McKinnon JJ, and Jayatilaka D, “Electrostatic potentials mapped on hirshfeld surfaces provide direct insight into intermolecular interactions in crystals.” CrystEngComm, 10, 377 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mulliken RS, “Electronic population analysis on LCAO–MO molecular wave functions. II. overlap populations, bond orders, and covalent bond energies.” J. Chem. Phys, 23, 1841 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tanabe I, Kurawaki Y, Morisawa Y, and Ozaki Y, “Electronic absorption spectra of imidazolium-based ionic liquids studied by far-ultraviolet spectroscopy and quantum chemical calculations.” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 18, 22526 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacFarlane DR, Kar M, and Pringle JM, Fundamentals of Ionic Liquids (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, Germany: ) (2017). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.