Abstract

The antibiotic cefiderocol hijacks iron transporters to facilitate its uptake and resists β-lactamase degradation. While effective, resistance has been detected clinically with unknown mechanisms. Here, using experimental evolution, we identified cefiderocol resistance mutations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Resistance was multifactorial in host-mimicking growth media, led to multidrug resistance and paid fitness costs in cefiderocol-free environments. However, kin selection drove some resistant populations to cross-protect susceptible individuals from killing by increasing pyoverdine secretion via a two-component sensor mutation. While pyochelin sensitized P. aeruginosa to cefiderocol killing, pyoverdine and the enterobacteria siderophore enterobactin displaced iron from cefiderocol, preventing uptake by susceptible cells. Among 113 P. aeruginosa intensive care unit clinical isolates, pyoverdine production directly correlated with cefiderocol tolerance, and high pyoverdine producing isolates cross-protected susceptible P. aeruginosa and other Gram-negative bacteria. These in vitro data show that antibiotic cross-protection can occur via degradation-independent mechanisms and siderophores can serve unexpected protective cooperative roles in polymicrobial communities.

Antimicrobial resistance is spreading faster than the development of new antibiotics and is a global threat1,2. Pseudomonas aeruginosa readily resists treatment due to the rapid emergence of antimicrobial resistance1,2. P. aeruginosa is an archetypal opportunistic pathogen and is a leading cause of nosocomial multidrug-resistant infections3. P. aeruginosa accounts for 10% of healthcare-associated acute urinary tract infections (UTIs)4, and P. aeruginosa drug resistance worsens UTI patient outcomes in people with chronic renal failure, advanced liver disease or diabetes mellitus5. P. aeruginosa also chronically infects approximately 80% of adults with cystic fibrosis, and these infections remain the primary cause of morbidity and mortality in people with cystic fibrosis6. Given P. aeruginosa’s intrinsic antibiotic resistance and its ability to evolve resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics, treatment options for P. aeruginosa infections are limited.

Cefiderocol was recently approved for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections, including UTIs, hospital-acquired bacterial pneumonia and ventilator-associated bacterial pneumonia. Cefiderocol has three structural features that support its antimicrobial activity: (1) a pyrrolidinium group that enhances stability against β-lactamase degradation, (2) a carboxypropanoxyimino group, similar to ceftazidime (CAZ), which improves transport across the outer membrane, and (3) a chlorocatechol moiety that confers siderophore activity7. Through its siderophore moiety, cefiderocol chelates ferric iron and is actively transported across the outer membrane via iron transport systems, such as P. aeruginosa PiuA and PiuD8–10. This transport overcomes outer membrane permeability issues that hinder drug development. Once delivered to the periplasm, iron dissociates, cefiderocol is released and, similar to other oxyimino-cephalosporins, inhibits peptidoglycan synthesis by binding penicillin-binding proteins (PBP), mainly PBP3 (ref. 11).

Compared to other cephalosporins, cefiderocol exposure leads to less frequent spontaneous drug resistance9,11,12. However, clinical isolates non-susceptible to cefiderocol have been reported13–15. As cefiderocol hijacks bacterial iron transporters to enter cells, it was proposed that iron transporter mutations could drive P. aeruginosa cefiderocol resistance11. Indeed, transposon (Tn) insertions in either piuA or piuC iron transport genes increase cefiderocol resistance 16-fold10,11. Likewise, other variants of genes related to iron acquisition and homeostasis were previously associated with cefiderocol resistance15,16. Moreover, cefiderocol acts as a substrate for the P. aeruginosa MexAB-OprM efflux pump, and a Tn insertion in a negative regulator of MexAB-OprM decreased cefiderocol susceptibility11,17. More recently, it was shown that variants of cpxS, a two-component system sensor, were detected in multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa strains evolved in increasing concentrations of cefiderocol18,19. However, cefiderocol-resistant isolates from individuals in clinical trials did not evolve mutations in iron transporters (piuA, piuC, pirA), cefiderocol’s target (ftsI) or β-lactamase genes20. Thus, cefiderocol resistance mutations remain incompletely characterized.

P. aeruginosa is notorious for its ability to adapt to host selective pressures. In the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis, P. aeruginosa adapts to osmotic stress, iron and other micronutrient deprivation, antibiotic selective pressures and oxidative stresses21. Adaptation to these pressures results in decreased metabolic activity, loss of quorum sensing, loss of motility apparatuses and the overproduction of alginate21–23. In the urinary tract, P. aeruginosa faces mechanical shear stress, hyperosmolarity, host immune factors and nutrient limitation. To thrive in these conditions, P. aeruginosa rewires its metabolism by decreasing fatty acid biosynthesis and phosphate uptake and increases secretion of virulence factors such as extracellular lipase, pseudolysin and alkaline protease24. In the urinary tract, P. aeruginosa also switches to a biofilm lifestyle; however, in contrast to cystic fibrosis biofilms, alginate is not the major component of the urinary tract biofilm matrix24. In both infections, host adaptation can increase antimicrobial resistance or tolerance25; however, the effects of these pressures on cefiderocol resistance has not been explored. Given that gene essentiality and pathoadaptation differs in distinct host environments26, we reasoned that cystic fibrosis and UTI environmental conditions would drive the selection of distinct cefiderocol resistance determinants. In addition to environmental conditions, the bacterial mode of growth can also affect resistance development. Comparisons of planktonic and biofilm resistance evolution using Acinetobacter baumannii and P. aeruginosa showed that structured populations evolved under sub-lethal ciprofloxacin (CIP) doses were more diverse relative to well-mixed populations which were more prone to experience selective sweeps of resistance mutations27,28. Because P. aeruginosa grows both as biofilm aggregates and planktonically during cystic fibrosis infections, we investigated how different bacterial lifestyles affected cefiderocol resistance evolution in P. aeruginosa.

In this Article, we used experimental evolution to identify chromosomal mutations underlying P. aeruginosa cefiderocol resistance evolving in two host-mimicking media: synthetic cystic fibrosis sputum (SCFM2) and synthetic human urine (SHU). We evolved strains in planktonic conditions (SCFM2 and SHU) and as biofilm aggregates (SCFM2) to mimic modes of growth likely to occur in both infections. This enabled us to ascertain whether media composition and mode of growth select for different cefiderocol resistance mechanisms. Because evolving antibiotic resistance is often associated with fitness costs, we evaluated the collateral phenotypic consequences of evolving cefiderocol resistance. We explored how resistance mechanisms affected competitiveness during cefiderocol treatment and propose a novel mechanism of cross-protection independent of β-lactamases. Altogether, this work determines mechanisms of cefiderocol resistance, as well as how intraspecies and interspecies interactions can affect population resistance to cefiderocol.

Results

Cefiderocol selects for multiple resistance mutations

We used experimental evolution to identify chromosomal mutations underlying cefiderocol resistance in P. aeruginosa in SCFM2 and SHU. We used planktonic conditions and biofilm aggregates to mimic modes of growth likely to occur in both infections (Supplementary Table 2).

We pre-adapted the P. aeruginosa ancestor strain to each growth medium for 10 days to reduce the influence of adaptation to the media on subsequent identification of resistance variants, as previous research indicated that most genetic adaptations to SCFM2 tend to occur within the first 10 days of selection29. Pre-adaptation in cystic fibrosis conditions led to 13 non-synonymous mutations in ptnB, codA, PA0863, napA, PA1232, PA1459, dnaX, PA2124, PA3214, PA3516, PA4341, PA4360 and ddpA identified by whole genome sequencing of the pre-adapted population (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 4). Pre-adaptation in SHU led to 11 non-synonymous mutations in ptnB, opdH, napA, PA1232, PA1459, dnaX, PA2124, PA3214, PA3516, PA4341, PA4360 and ddpA. Genes mutated in the host-mimicking media were mainly associated with energy metabolism, transport of small molecules, chemotaxis and DNA replication, reflecting adaptation to nutritional cues in these media (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 4). These mutations served as a baseline for cefiderocol adaptation, and genes mutated in the pre-adaptation stage were not considered in subsequent analyses as candidate cefiderocol resistance mutations.

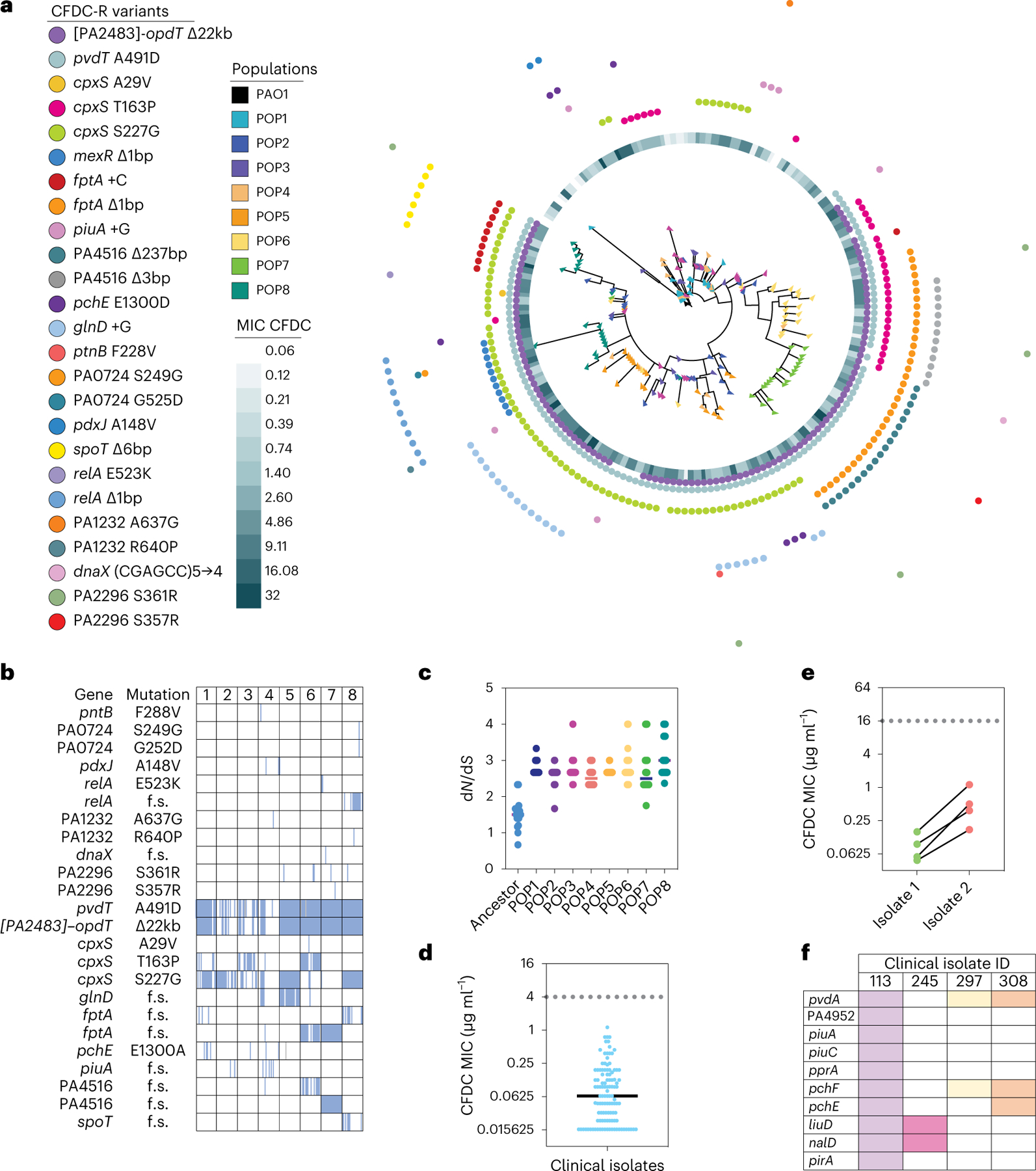

Fig. 1 |. Cefiderocol resistance variants affect multiple genes and pathways.

a, Experimental design: P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 was propagated in SCFM2 or SHU for 10 days before cefiderocol exposure. Pre-adapted populations were propagated daily in increasing cefiderocol concentrations planktonically in SHU or SCFM2 and as agar biofilm block assay biofilm aggregates in SCFM2. When evolved populations achieved growth at 1,024 µg µl−1 cefiderocol, evolved populations were collected and sequenced to identify cefiderocol resistance mutations. As controls, eight populations for each medium and lifestyle were propagated in antibiotic-free conditions. b, Cefiderocol resistance increased during experimental evolution. Population-level cefiderocol MICs were calculated using broth microdilution in either SCFM2 or SHU (n = 8 parallel populations, mean ± s.e.m.). c, Heat map of non-synonymous mutations detected after pre-adaptation of PAO1 in SCFM2 and SHU media, including PseudoCAP functional categories for each gene. These gene mutations served as a baseline for cefiderocol adaptation and were not considered in subsequent analyses as candidate cefiderocol resistance mutations. d, Heat map of non-synonymous mutations detected in populations evolved to grow at 1,024 µg ml−1 cefiderocol in SCFM2 (planktonic and aggregates) and SHU. Variants detected in at least 5% of cells in any given population are listed. Each column represents one replicate population, and colour intensity indicates the relative frequency of each gene variant detected in each population. e, Heat map of antimicrobial susceptibilities of mutants with Tn insertions in candidate resistance genes identified via experimental evolution. Results indicate the average fold change in MIC in the Tn mutants compared to the PAO1 wild-type strain (n = 3 independent experiments). CFDC, cefiderocol; WT, wild type; CEP, cefepime; CFDCS, CFDC susceptible; CFDCR, CFDC resistant.

Pre-adapted populations were passaged in increasing cefiderocol concentrations either planktonically in broth or as aggregates in agar medium mimicking cystic fibrosis until each population achieved growth at 1,024 µg ml−1 cefiderocol (Fig. 1a). In parallel, bacteria were passaged without antibiotics as controls. Clinical resistance30 was achieved in less than 1 week in each medium: first in human urine, followed by cystic fibrosis aggregates, which were significantly faster than cystic fibrosis planktonic populations (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1a). However, the cystic fibrosis planktonic populations achieved growth at high concentrations of cefiderocol (1,024 µg ml−1) fastest, followed by urine planktonic populations, and cystic fibrosis aggregate populations achieved growth more slowly after 20 days (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 5). These data show that the nutritional environment and mode of growth affected rates of cefiderocol resistance emergence.

To determine cefiderocol resistance mutations, we performed whole genome sequencing on the evolved populations and compared them to the pre-adapted ancestral populations. Evolved populations were genetically diverse, showing few mutations fixed within each population and several mutations at low frequencies (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 5). Shannon diversity indices of cefiderocol-evolved populations selected on SHU were higher than control populations, suggesting that multiple mutations confer selective advantages in urine-mimicking media with cefiderocol (Extended Data Fig. 2). Candidate cefiderocol resistance mutations affected some genes previously associated with cefiderocol resistance, including piuA (ref. 11). However, new gene variants were also associated with resistance. Two genes were mutated in at least one replicate of all host-mimicking conditions: pchE and argJ. Other mutations were selected in distinct environments. Multiple mutations in the cpxS two-component sensor gene were detected in cystic fibrosis-evolved populations, but no cpxS mutations were detected in urine-evolved populations. Mutations in PA0719, encoding a bacteriophage hypothetical protein, were fixed in some planktonic populations, but not in aggregates. In addition, a large 21,938 base-pair deletion arose exclusively in cystic fibrosis populations. Together, these results suggest that some mutations contributed to cefiderocol resistance generally, while other mutations specifically increased resistance under certain nutrient or growth conditions.

Analyses of Tn mutants for genes that were mutated during experimental evolution showed that, in agreement with previous studies, piuA or piuC disruption resulted in fourfold increases of cefiderocol resistance12, while the PA3303 mutant, which served as a neutral Tn insertion negative control, was not more resistant to cefiderocol or related antibiotics (Fig. 1e). As predicted, disruption of genes associated with iron acquisition, such as pyochelin (pchEF) siderophore biosynthesis genes, led to twofold to eightfold increases in resistance, as did mutations in cpxS, nalD and PA2550. Unexpectedly, Tn insertions in pprA, PA3423, PA4952 and PA2473 had no effect on cefiderocol resistance. While it is unclear why these mutants did not increase cefiderocol resistance, it is possible that the point mutations detected in experimental evolution act as gain of function in these genes. If this is true, then Tn mutants would fail to recapitulate the resistance, because they would lead to loss of protein function. Alternatively, these mutations might represent compensatory mutations rather than direct cefiderocol resistance mutations.

To better understand how mutations individually or additively contribute to cefiderocol resistance, we performed susceptibility testing and whole genome sequencing on individual clones from the evolved cystic fibrosis planktonic populations. From each of the 8 evolved populations 20 clones were analysed, including 20 clones from the pre-adapted ancestor population. In general, cefiderocol susceptibilities were lower than those observed for mixed populations, ranging from 0.0125 to 32 µg ml−1, suggesting that inter-clonal cooperative interactions promote higher resistance.

Excluding mutations that were detected in the pre-adapted clones, relatively few mutations were detected in individual clones: 0–9 total mutations, including 0–6 non-synonymous, 0–3 synonymous and 0–1 intergenic mutations detected in each clone (Fig. 2a,b, Extended Data Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 6). The ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous mutations (dN/dS) showed that strains were under positive selection (dN/dS > 1, range 0.66–4; Fig. 2c), reflecting the cefiderocol selective pressure. Similar to the whole populations, cpxS was recurrently mutated in individual cefiderocol-evolved clones, including 118 out of 160 clones across 6 different populations (either T163P or S227G; Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Table 6). Mutations were also recurrently detected in iron homeostasis genes, such as pchE, fptA, pvdT, PA4516 and piuA. In addition, frameshift mutations in mexR, a negative regulator of the MexAB-OprM efflux pump, were detected in 10 colonies from one population (Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Table 6). While the mexR mutation was not detected during whole population analyses, it is possible that mexR mutants were initially present in less than 5% of cells in a population (variant calling cutoff) and might have been further selected by cefiderocol pressure imposed while collecting individual colonies for clonal analyses. Together, these findings highlight that disruption of iron homeostasis, as well as mutations increasing the expression of efflux pumps, contribute to cefiderocol resistance. Surprisingly, we detected 12 evolved clones that did not carry any new mutations that arose during the cefiderocol experimental evolution, suggesting that cooperation may play an important role in cefiderocol resistance.

Fig. 2 |. Cefiderocol resistance variants detected in evolved clones and P. aeruginosa clinical isolates.

a, Whole genome maximum-parsimony phylogenetic tree constructed from mutations detected in 180 isolated evolved colonies (20 ancestor and 160 SCFM2 planktonic cefiderocol-evolved colonies, 20 per population, indicated by coloured triangles). Tree was rooted using PAO1. Cefiderocol MICs for each isolate are presented as a heat map, and coloured dots indicate SNVs detected in each clone. b, Heat map showing mutations detected in isolated colonies in the eight SCFM2 planktonic cefiderocol-evolved populations. A full coloured square indicates a fixed mutation. f.s., frameshift mutation. c, The ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous mutations (dN/dS) per colony in ancestor and eight SCFM2 planktonic cefiderocol-evolved populations (lines indicate the mean dN/dS for each population; n = 20 colonies per population). d, Cefiderocol MICs of P. aeruginosa clinical isolates from patients with acute and chronic pneumonia who were never treated with cefiderocol (n = 113 independent clinical isolates; dotted line, MIC breakpoint for cefiderocol resistance; solid line, mean). e, Increased cefiderocol MICs in paired sequential clinical isolates. While not technically cefiderocol resistant (MIC > 4 µg ml−1), clinical isolate pairs were recovered from the same patient in which one isolate showed an increased cefiderocol MIC relative to the other (n = 4 pairs of independent clinical isolates). f, Heat map indicating mutations in genes identified as being under selection during cefiderocol experimental evolution in clinical isolates with reduced cefiderocol susceptibility. Columns and colours represent each clinical isolate. CFDC-R, CFDC resistant.

We next asked whether resistance mutations detected in the laboratory were also present in clinical isolates. We determined cefiderocol susceptibilities of 113 P. aeruginosa clinical isolates from intensive care unit (ICU) patients who were never treated with cefiderocol. While all the clinical isolates were clinically susceptible to cefiderocol (Fig. 2d)30, we identified four clonally related clinical isolate pairs in which one isolate showed at least 3.5-fold higher cefiderocol minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) compared to the more susceptible isolate (Fig. 2e). Whole-genome sequencing showed that some of the recurrent resistance mutations detected in the evolution experiment were also mutated in more resistant clinical isolates (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Table 6). Notably, these mutations primarily affected candidate resistance genes involved in iron acquisition, including iron-binding siderophore biosynthesis and receptor genes. It is possible that variants or genes in the clinical isolate accessory genomes could also affect cefiderocol resistance. Future work would need to analyse accessory genes and their mutations to determine potential effects on cefiderocol resistance. However, these data suggest that host selective pressures affecting iron may also affect cefiderocol susceptibilities, even in the absence of cefiderocol treatment.

Drug-free conditions restore susceptibility

To test whether specific cefiderocol resistance variants paid fitness costs in the absence of cefiderocol, we passaged cefiderocol-resistant populations in drug-free media and measured cefiderocol susceptibilities over time. All populations reverted to become cefiderocol susceptible, regardless of the medium or mode of growth (Fig. 3a). Whole-genome sequencing showed that reverted populations in cystic fibrosis media exhibited the 23-gene deletion that was recurrently observed during cystic fibrosis cefiderocol resistance evolution. This finding suggests that this deletion is an adaptation to the cystic fibrosis medium rather than a mutation associated with cefiderocol resistance. In the cefiderocol-free environments, femR, fpvK, cupE1, argJ and dnaX were recurrently mutated in cystic fibrosis planktonic populations, whereas PA1297, mexY, argJ, pprA and pprB mutations emerged in cystic fibrosis aggregates (Fig. 3b). Variants of PA1232 and clpA were fixed across human urine populations propagated in the absence of cefiderocol. By contrast, cpxS variants were not maintained in cystic fibrosis planktonic populations evolved in the absence of cefiderocol, indicating that cpxS variants pay fitness costs in drug-free environments (Fig. 3b). These findings motivated the investigation of the secondary phenotypic consequences of cefiderocol resistance.

Fig. 3 |. Evolved cefiderocol resistance pays fitness costs.

a, Change in cefiderocol MICs in cefiderocol-resistant evolved populations during continuous passaging for 14 days in cefiderocol-free SCFM2 or SHU (dotted line, cefiderocol susceptibility breakpoint, MIC < 4 µg µl−1, defined by the US Food and Drug Administration; individual population MICs are indicated in grey; red lines indicate daily mean MIC ± s.e.m., n = 8 populations). b, Heat maps indicate the mean frequencies of genetic mutations that increased or decreased in prevalence after 14 days of propagating populations in cefiderocol-free media. Pie charts indicate the fraction of 8 populations in which the mutations were detected either before or after susceptibility was restored. Arrows indicate whether mutations increased or decreased in frequency after populations became susceptible. c, Antimicrobial susceptibilities of cefiderocol-resistant populations compared to untreated control populations (mean fold change ± s.d. in MIC comparing eight evolved populations to control populations; each point indicates mean of three independent experiments per population). d, Growth of evolved and untreated control populations in the absence of cefiderocol in SCFM2 or SHU (two-sided unpaired t-test, mean of eight evolved populations ± s.d.; compared to one control population with three independent experiments per population). m, minutes. e, In vitro competition between ancestral (mApple) and evolved populations (eYFP). CI > 1 indicates that evolved populations outcompeted their ancestors (two-sided unpaired t-test; competitions were performed three times per evolved population; mean CI is indicated for each competition). TOB, tobramycin; COL, colistin; PMB, polymyxin B.

Cefiderocol selects for cross-resistance

To determine whether the evolution of cefiderocol resistance affected susceptibility to other drugs, we measured susceptibilities of cefiderocol-evolved populations to a range of clinically relevant antibiotics. Compared with untreated control populations, cefiderocol-resistant evolved populations were more resistant to other cephalosporins, aztreonam (ATM) and tobramycin (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 10). In addition, cefiderocol-resistant populations evolved in cystic fibrosis conditions were more resistant to polymyxin B and colistin (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 10). Populations evolved in urine mimicking conditions were slightly more resistant to CIP (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 10). Cross-resistance can be explained by mutations in genes that regulate antibiotic efflux pumps. We hypothesized that cpxS and nalD variants (Figs. 1d and 2a,b) were driving cross-resistance. The nalD gene encodes a repressor of the mexAB-oprM efflux pump operon, and nalD variants show multidrug resistance31,32. However, while the CPX two-component system regulates mexAB-oprM and muxABC-opmB expression via promoter activation by CpxR33, it is not clear how cpxS sensor variants would impact the expression of these efflux pumps. Thus, we measured the expression of mexAB-oprM and muxABC-opmB in the cpxS variants selected during experimental evolution. While cpxSV235A did not change efflux pump expression, cpxST163P and cpxSS227G variants respectively increased mexA expression by 1.8- and 3.5-fold and muxA expression by 8.1- and 32.1-fold (Extended Data Fig. 4a; n = 6, analysis of variance (ANOVA) P < 0.0001). Next, we tested whether cross-resistance was lost once cefiderocol pressure was alleviated. After continuous passaging in the absence of cefiderocol, susceptibility to CAZ and cefepime was restored (Extended Data Fig. 4b). These findings can be explained by the loss of the cpxS mutations in the drug-free environments (Fig. 3b).

Cefiderocol resistance pays fitness costs

Considering that cefiderocol resistance was lost in the absence of antibiotic pressure, we hypothesized that cefiderocol resistance would pay fitness costs in the absence of cefiderocol. Indeed, highly resistant populations selected in cystic fibrosis conditions showed significantly slower growth rates (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 10). By contrast, evolved populations selected in urine medium did not show significant growth defects (Supplementary Table 10).

To further investigate the relationship between cefiderocol resistance and fitness, we tested the competitiveness of evolved populations against their ancestors in the presence or absence of cefiderocol. In the absence of cefiderocol, ancestral populations outcompeted cefiderocol-resistant evolved populations in the cystic fibrosis environment. However, in urine co-culture both evolved and ancestral populations were equally competitive, indicating that cefiderocol resistance mutations acquired in urine medium paid little or no fitness costs in the absence of cefiderocol (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 5).

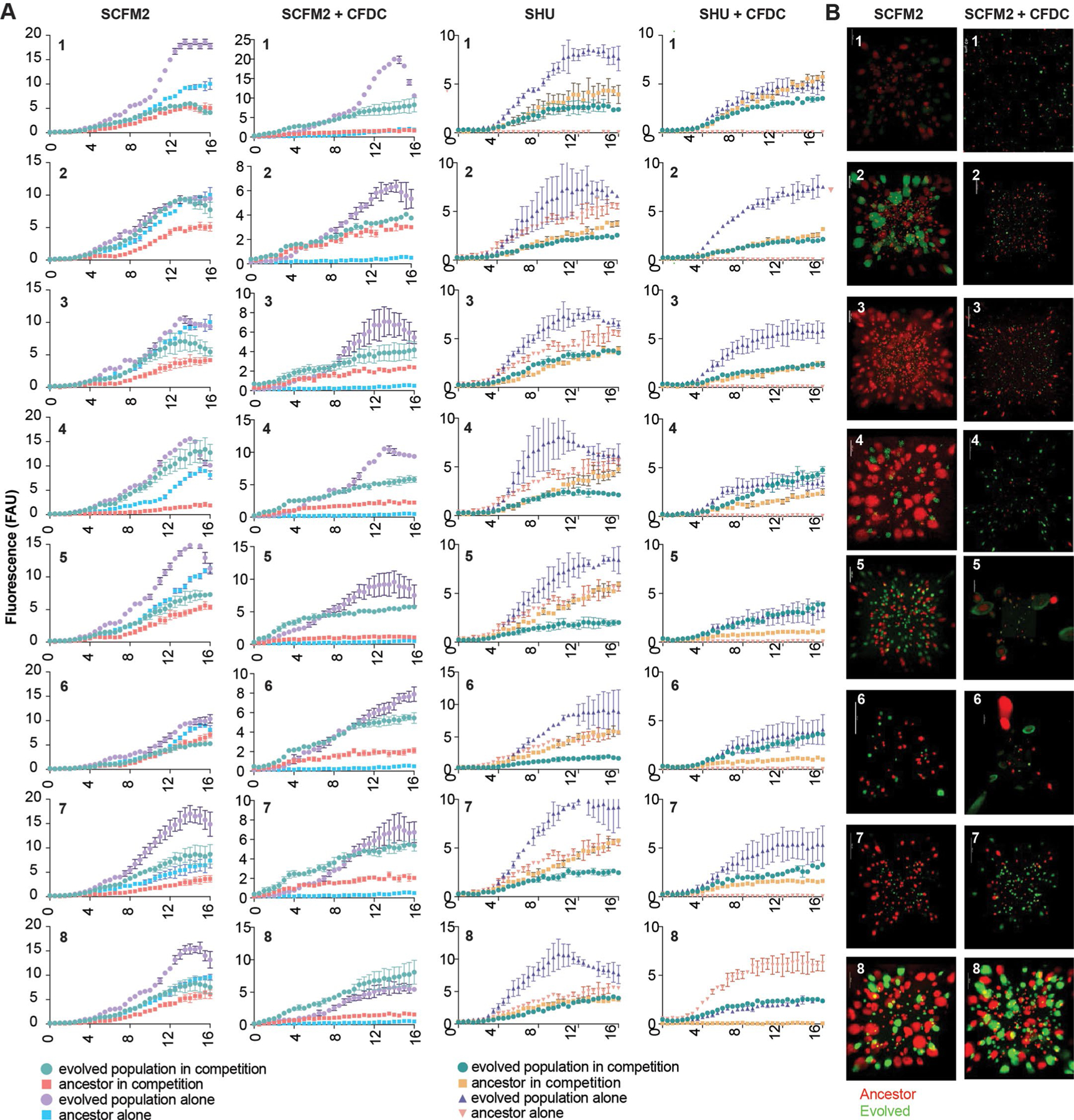

Cefiderocol selects for cooperative cross-protection

Each cefiderocol-evolved population’s fitness was also evaluated in the presence of cefiderocol. As expected, all urine-adapted cefiderocol-resistant populations were more fit than the susceptible ancestors in high cefiderocol concentrations (64 µg ml−1) (Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 5). Moreover, five of eight cystic fibrosis-evolved populations outcompeted the susceptible populations when cefiderocol was present (Figs. 3e and 4a,b). Unexpectedly, three evolved cystic fibrosis planktonic populations grew at the same rate as ancestral susceptible populations during cefiderocol co-culture (Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 5). The growth of the ancestral susceptible population was surprising because it cannot grow in high cefiderocol concentrations in isolation (Extended Data Fig. 6). The unexpected growth during cefiderocol exposure is indicative of kin selection34, whereby cooperative sub-populations are selected for because they produce a public good which allowed cefiderocol-susceptible individuals to grow in otherwise lethal cefiderocol concentrations. The cooperative protective phenotype was also observed in the two aggregate conditions, where cefiderocol-resistant evolved populations grew in the outermost layers of the aggregate, potentially shielding the cefiderocol-susceptible ancestral population from cefiderocol killing (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 5). Such cooperative behaviour did not arise in populations evolved in urine medium, suggesting that kin selection is acting exclusively in the cystic fibrosis environment.

Fig. 4 |. Cross-protection evolved in cefiderocol-resistant populations.

a–d, As expected, in vitro competitions revealed that most evolved populations outcompeted ancestors in SCFM2 under high cefiderocol pressure (64 µg ml−1) both in planktonic (a, mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 independent experiments) and in biofilm conditions (b). However, some cefiderocol-resistant populations evolved cooperative social behaviour allowing ancestral cefiderocol-susceptible cells to survive cefiderocol insult in well-mixed planktonic (c, mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 independent experiments) and structured aggregate biofilm environments (d). Representative 3D confocal micrographs of non-protective (b) and protective (d) interactions between cefiderocol-resistant evolved populations (green) and ancestral susceptible populations (red) in the presence of 64 µg µl−1 cefiderocol (a–d, eight populations were tested with three independent experiments each). RFU, relative fluorescence units. e, Heat map showing differential gene expression in protective and non-protective interactions under 64 µg ml−1 cefiderocol pressure (log2 fold change indicated; cutoff, >1.5 log2 fold change and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05). f, Volcano plot highlighting differentially expressed genes in protective compared to non-protective interactions (DEG, differentially expressed gene; adjusted P < 0.05 with log2 fold change of >1.5). g, Cefiderocol MICs of PAO1 and cpxS variants (mean ± s.e.m., ANOVA, n = 8 independent experiments). h, Planktonic competitions of PAO1 and cpxS variants (T163P, S227G, V235A) in SCFM2 with ½ × cefiderocol MIC. The growth of PAO1 was measured by mApple fluorescence area under the curve (AUC; mean ± s.e.m., ANOVA, n = 3 independent experiments). i, Biofilm competition between PAO1 and cpxSS227G in SCFM2 in the absence (left) and presence (right) of 2 µg ml−1 cefiderocol. Representative confocal micrograph from a single experiment is shown.

Sensor variants drive cooperative cross-protection

We next asked which P. aeruginosa traits drove the cross-protection of cefiderocol-susceptible cells. We compared the gene expression profiles of protective versus non-protective co-cultures in the presence of cefiderocol using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). These transcriptome analyses revealed that protective co-cultures had 34 differentially expressed genes, including 16 upregulated and 18 downregulated genes (Fig. 4e,f and Supplementary Table 9). Surprisingly, no public goods related to β-lactam degradation, such as β-lactamases, were increased in expression in the protective co-cultures. However, protective co-cultures upregulated CPX two-component system genes and the muxABC-opmB efflux pump. MuxABC-OpmB plays a role in resistance to novobiocin, ATM, macrolides and tetracycline, and its overexpression is associated with modest increases in pyoverdine secretion35.

The upregulation of genes under control of the CPX two-component system motivated us to further analyse its role in cooperative cross-protection. We tested three cpxS variants’ abilities to cross-protect the parental strain. While cpxST163P and cpxSV235A variations had little effect on cefiderocol resistance, the cpxSS227G variant had a fivefold higher cefiderocol MIC (Fig. 4g). Moreover, cpxSS227G was able to cross-protect strain PAO1 from cefiderocol killing (Fig. 4h,i). Cross-protection in biofilm communities has been primarily associated with β-lactamase mediated drug inactivation36,37. However, ampC was not differentially expressed during cross-protective interactions. Considering that muxABC-opmB was upregulated during cross-protective interactions (Fig. 4e,f) and in individual cpxS variants (Extended Data Fig. 4), as well as the role of MuxABC-OpmB in pyoverdine secretion, we reasoned that pyoverdine secreted by MuxABC-OpmB could act as a cooperative public good protecting the susceptible cells.

In the presence of sub-inhibitory cefiderocol, cpxSS227G alone and in co-cultures with PAO1 increased pyoverdine production compared to PAO1 alone (Fig. 5a). Checkerboard susceptibility assays combining cefiderocol and P. aeruginosa siderophores (pyoverdine and pyochelin) revealed opposing effects on cefiderocol activity: pyochelin increased cefiderocol efficacy, while pyoverdine antagonistically decreased cefiderocol activity against PAO1 (Fig. 5c). Previously, it was shown that pyoverdine had a greater ability to chelate Fe(III) than cefiderocol9. Hence, we hypothesized that pyoverdine attenuates cefiderocol activity by displacing Fe(III) from cefiderocol. Iron displacement was measured by fluorescence quenching of pyoverdine, and at equimolar amounts pyoverdine chelated Fe(III) from ferric cefiderocol (Fig. 5b). The roles of P. aeruginosa siderophores in cefiderocol tolerance extended to clinical isolates. ICU clinical isolates’ endogenous pyoverdine production correlated with cefiderocol susceptibilities (Fig. 5d). By contrast, pyochelin was not correlated with cefiderocol susceptibility (Fig. 5e). Similarly, pyoverdine production in individual cefiderocol experimentally evolved clones correlated with cefiderocol susceptibility (Extended Data Fig. 7). These findings collectively indicate that increased pyoverdine production represents a phenotypic mechanism to increase cefiderocol resistance (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5 |. The role of pyoverdine in cross-protection.

a, Pyoverdine (RFU: excitation, 400 nm; emission, 460 nm) production by PAO1 and cpxS variants (T163P, S227G and V235A) in SCFM2 with sub-inhibitory cefiderocol (mean ± s.e.m., ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, n = 4 independent experiments). b, Pyoverdine removes iron from cefiderocol. Iron binding to pyoverdine indicated by fluorescence quenching: as pyoverdine binds free iron or iron from cefiderocol, fluorescence decreases (mean ± s.d., n = 2 independent experiments). Lines indicate fluorescence of molecules alone, after pre-incubation with 100 µM FeCl3, or after incubation with iron-loaded pyoverdine. RFU, relative fluorescence units. c, Changes in cefiderocol susceptibility in the presence of pyoverdine (PVD) and pyochelin (PCH) expressed by log2 cefiderocol fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) (mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 independent experiments). d, Pyoverdine production by P. aeruginosa ICU clinical isolates in relation to cefiderocol susceptibility (Spearman correlation, n = 113 clinical isolates). e, Pyochelin production by P. aeruginosa ICU clinical isolates in relation to cefiderocol susceptibility (Spearman correlation, n = 113 clinical isolates). f, Pyoverdine protects K. pneumoniae (Kp), E. coli (Ec), B. cenocepacia (Bc) and B. multivorans (Bm) from cefiderocol killing in a dose-dependent manner. The change in MIC is expressed by the log2 cefiderocol FIC (n = 6 independent experiments, mean ± s.d.). g,h, Interspecies planktonic competitions between P. aeruginosa PAO1::mApple or cpxSS227G::mApple and K. pneumoniae::eYFP (g) or E. coli::eYFP (h) in the presence of inhibitory cefiderocol. Growth of K. pneumoniae and E. coli were measured by eYFP fluorescence AUC (mean ± s.e.m., ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test, n = 5 independent experiments). i,j, Interspecies planktonic competitions between P. aeruginosa clinical isolates (121a, a low pyoverdine producer, and 172aC, high pyoverdine producer) and K. pneumoniae (i) or E. coli (j) in the absence of antibiotics. k,l, Interspecies planktonic competitions between P. aeruginosa clinical isolates (121a and 172aC) and K. pneumoniae (k) or E. coli (l) in the presence of cefiderocol. For i–l, K. pneumoniae and E. coli were quantified by CFUs (mean ± s.e.m., n = 4 independent experiments; dashed line, limit of detection). m, Pyoverdine production in P. aeruginosa PAO1 and cpxSS227G strains in co-culture with K. pneumoniae or E. coli in the presence of cefiderocol (mean ± s.e.m., ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test, n = 4 independent experiments). n, Pyoverdine production in P. aeruginosa 121a and 172aC clinical isolates in co-culture with K. pneumoniae or E. coli in the presence of cefiderocol (mean ± s.e.m., ANOVA, Kruskal–Wallis test, n = 4 independent experiments).

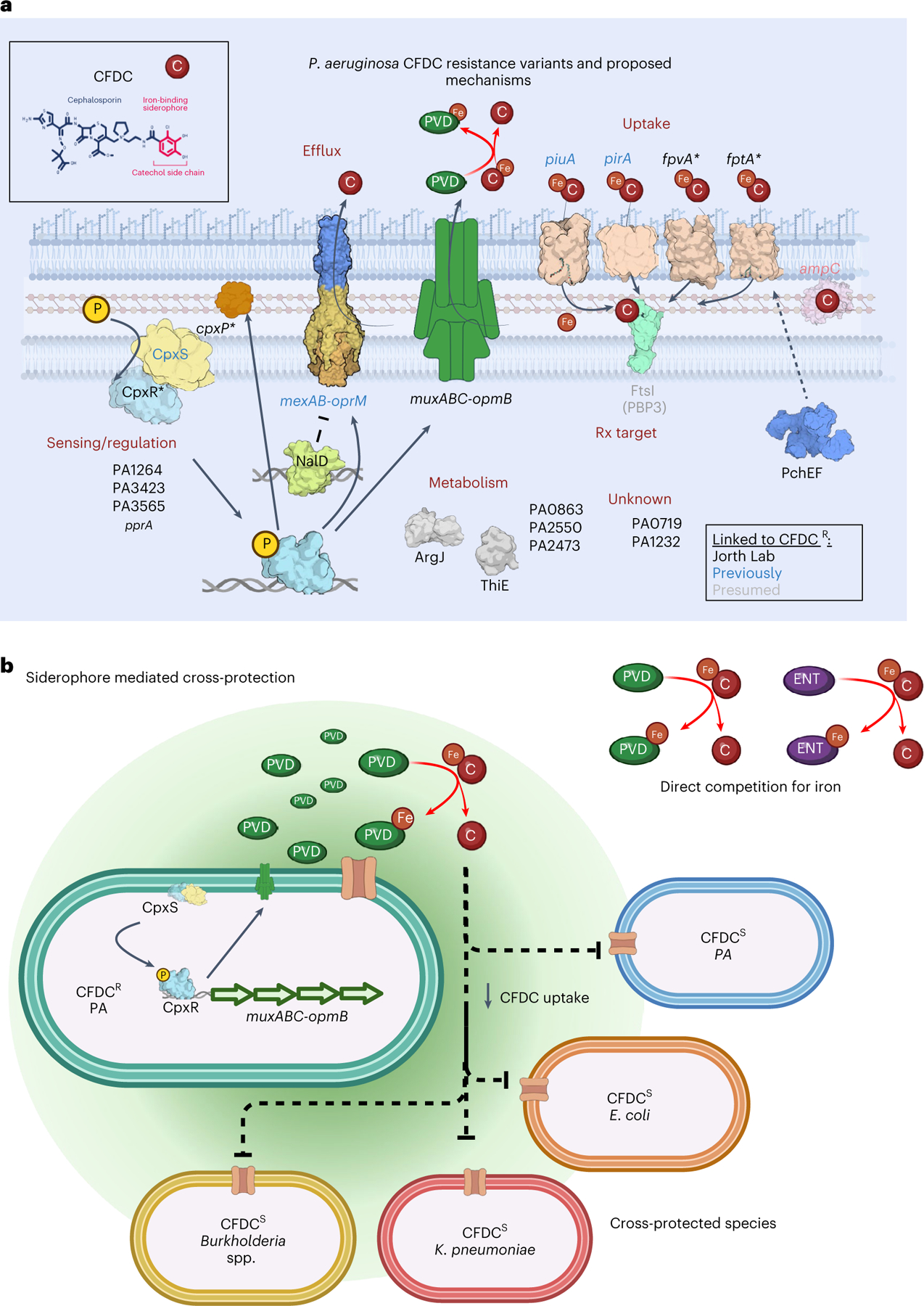

Fig. 6 |. Cefiderocol resistance and cross-protection mechanisms.

a, Cefiderocol resistance is multifactorial. We identified variants arising under continuous cefiderocol pressure in genes associated with drug uptake, drug efflux, transcriptional regulation, metabolism and hypothetical genes of unknown function. Mutations in transcriptional regulators (nalD) or two-component systems (cpxS) likely regulate the expression of efflux pumps (mexAB-oprM) or iron transporters (piuA, pirA, fpvA, fptA) involved in cefiderocol uptake. Although drug target modification is a common mechanism of resistance, we did not detect mutations in ftsI (PBP3, labelled in grey). Therefore, cefiderocol resistance is primarily driven by increased drug efflux or limiting cefiderocol uptake. Another resistance mechanism involved increased pyoverdine secretion (via muxABC-opmB), which chelates iron from cefiderocol and restrains its uptake. b, Bacterial siderophores act as public goods and promote bacterial cross-protection via cooperation. Cefiderocol must be in its ferric form to be transported inside bacterial cells. Siderophores with high affinities for ferric iron can directly displace iron from cefiderocol, which limits its uptake. Susceptible P. aeruginosa cells and members of polymicrobial communities are cross-protected by the secretion and diffusion of pyoverdine benevolently produced by cefiderocol-resistant cooperators.

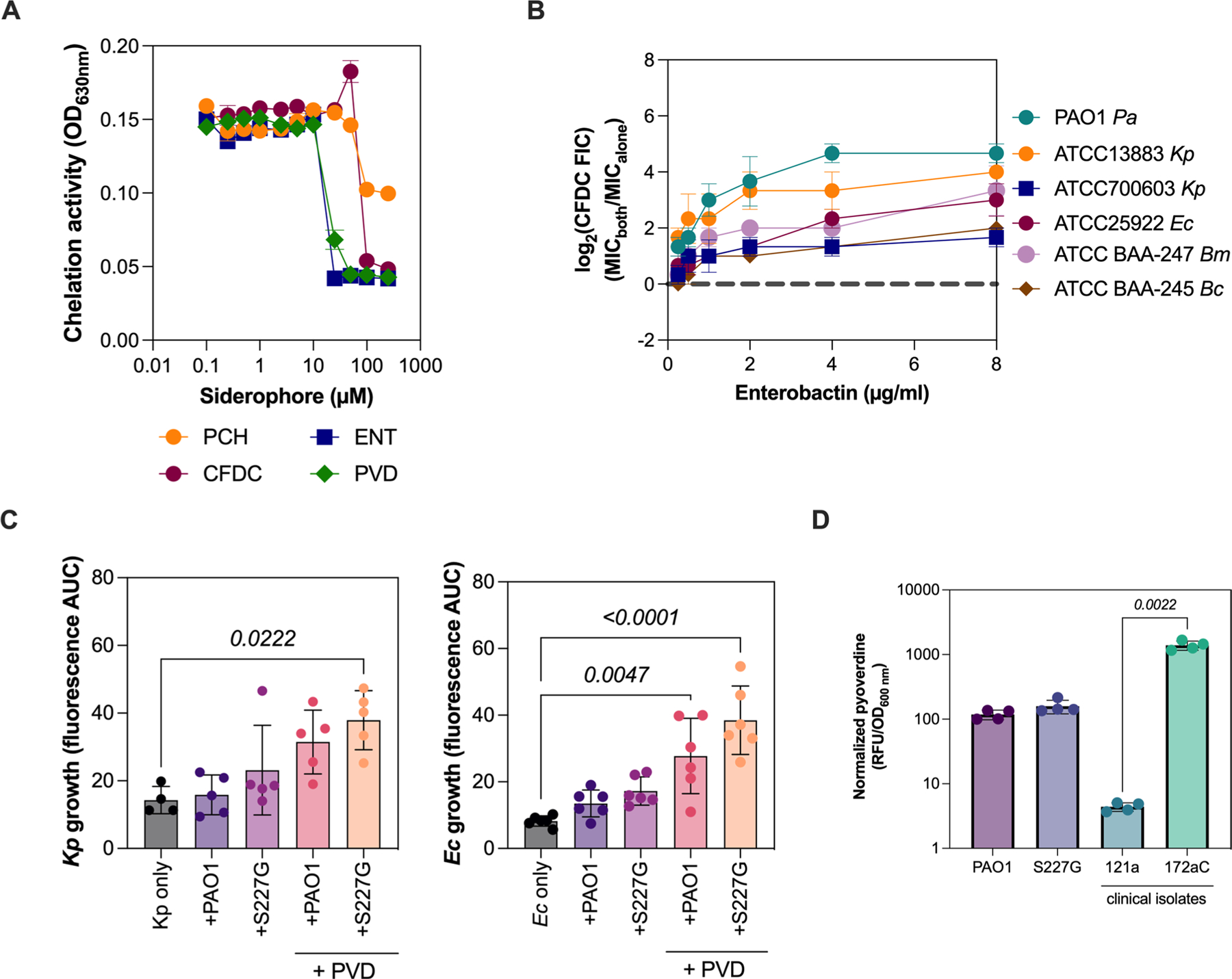

Because P. aeruginosa siderophores had opposing effects on cefiderocol killing, we asked whether a siderophore produced by other pathogens would enhance or reduce cefiderocol killing. Using an iron chelation assay, we found that the enterobacteria siderophore enterobactin had greater iron affinity than cefiderocol (Extended Data Fig. 8a). This led us to question whether bacterial siderophores that are typically thought of as interspecies competitive factors could instead act broadly as cooperative factors and prevent cefiderocol killing. Both pyoverdine and enterobactin reduced cefiderocol killing of P. aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Burkholderia cenocepacia and Burkholderia multivorans (Fig. 5f and Extended Data Fig. 8b).

The protective effects of siderophores led us to ask whether their production in co-culture could drive interspecies cross-protection. While PAO1 was unable to cross-protect other species, cpxSS227G cross-protected K. pneumoniae and E. coli from cefiderocol killing (Fig. 5g,h). As expected, cpxSS277G cross-protection correlated with its increased pyoverdine production relative to PAO1 (Fig. 5m), and the supplementation of exogenous pyoverdine further protected K. pneumoniae and E. coli from cefiderocol killing (Extended Data Fig. 8c). Finally, we asked whether P. aeruginosa clinical isolates could drive interspecies cefiderocol cross-protection. We compared the cross-protective abilities of two P. aeruginosa clinical isolates that produced high (isolate 172aC) and low amounts of pyoverdine (isolate 121a) (Extended Data Fig. 8d). The high pyoverdine producing isolate 172aC cross-protected both K. pneumoniae and E. coli, while the low pyoverdine producing isolate 121a did not (Fig. 5i–l,n and Extended Data Fig. 8d). Together these results support the hypothesis that cefiderocol cross-protection is conferred by variants with increased pyoverdine secretion which competes for iron, limiting cefiderocol uptake by bacterial cells.

Discussion

Using experimental evolution, we investigated mechanisms of cefiderocol resistance and secondary phenotypic effects of cefiderocol resistance in P. aeruginosa. Populations in cystic-fibrosis- and urine-mimicking media achieved high levels of cefiderocol resistance; however, both the nutritional environment and the mode of growth (for example, planktonic versus aggregate growth) selected for different cefiderocol resistance mutations, suggesting that cefiderocol resistance mutations might have conditional fitness costs38. Several genes were recurrently mutated in multiple populations, and this parallelism reflects the selection of beneficial traits under cefiderocol pressure39. A secondary consequence of cefiderocol resistance evolution was the development of multidrug resistance, which raises concerns about cefiderocol use in patient care. However, these concerns are tempered by the following: (1) fitness costs paid by cefiderocol-resistant strains that are outcompeted by susceptible siblings in the absence of cefiderocol and (2) experiments showing that cefiderocol susceptibility could be restored in populations passaged in cefiderocol-free conditions. Concerns remain, however, because some resistant populations cross-protected susceptible cells during cefiderocol exposure.

Cross-protective cooperation mediated by β-lactamases has been described36,37; however, our findings indicate that cefiderocol cross-protection is AmpC-independent. In protective co-cultures, cpxS and the cpxR-regulated muxABC-opmB efflux pump33 were overexpressed. We showed that the cpxSS227G variant cross-protected wild-type PAO1, suggesting that conformational changes in the CpxS sensor kinase might lead to CPX hyperactivation. Previously, mutations of the cpxS homolog cpxA were shown to prevent CpxA interactions with CpxP, resulting in continuous CPX activation40. We hypothesized that increased muxABC-opmB expression could cooperatively cross-protect susceptible cells by increasing pyoverdine secretion. While not required for siderophore secretion, MuxABC-OpmB contributes to the secretion of coumarin-containing compounds, including pyoverdine41. Indeed, muxA expression and pyoverdine secretion were elevated in the cpxSS227G mutant. Alternatively, MuxABC-OpmB might actively efflux cefiderocol. Previously, it was shown that CpxR, which regulates muxABC-opmB expression, is activated by CAZ treatment42. However, whether cephalosporins and cefiderocol are MuxABC-OpmB substrates is yet to be determined.

The selection for cpxS- and pyoverdine-mediated cooperative cross-protection can be explained through kin selection theory, which posits that cooperative social traits that benefit closely related organisms will be selected for when populations are most homogenous34,43,44. In this case, closely related P. aeruginosa cpxS variants overproducing the public-good pyoverdine were selected for recurrently in the presence of cefiderocol. In theory, traits under kin selection should be subject to cheating and be deleterious. This is evident in cystic-fibrosis-evolved P. aeruginosa where social traits regulated by quorum sensing are prone to cheating and are often lost in evolution, consistent with kin selection45–48. We observed that in the absence of cefiderocol, cpxS variants were outcompeted, indicating fitness costs tied to cooperation. We also show that enterobactin can cross-protect against cefiderocol killing. However, whether enterobactin overproducers arise in response to cefiderocol pressure and whether enterobactin producers are prone to social cheating are unknown.

We showed that bacterial siderophores can have opposing effects on cefiderocol susceptibility: pyoverdine and enterobactin increased resistance, and pyochelin increased P. aeruginosa susceptibility. Pyochelin sensitization was previously associated with increased cefiderocol uptake by fptA overexpression10. Hence, pyochelin or new molecules that induce fptA expression could improve cefiderocol efficacy. Although this study focuses on P. aeruginosa cefiderocol resistance mechanisms, we showed that enterobactin can also antagonize cefiderocol. Therefore, we anticipate that Enterobacteriaceae mutations leading to enterobactin overproduction would also drive cefiderocol tolerance and cross-protection. Pyoverdine-mediated protection is consistent with previous investigations. A study of another siderophore-conjugated antibiotic and conference proceedings investigating cefiderocol resistance mechanisms found that mutations in the promoter region of pvdS, a sigma factor that regulates the expression of pyoverdine biosynthesis genes, led to pvdS overexpression, increasing pyoverdine production and resistance to cefiderocol and a related compound12,49. Likewise, endogenous and exogenous pyoverdine reduced efficacy of the siderophore-conjugated antibiotic MB-1 (ref. 50), which we demonstrate is also true for cefiderocol. However, we showed P. aeruginosa can increase pyoverdine secretion independent from pvdS mutations. Furthermore, we show that pyoverdine directly chelates iron from cefiderocol showing that the mechanism does not depend on altered pyoverdine transporter expression or cefiderocol degradation, which was proposed previously50. During chronic cystic fibrosis infections, P. aeruginosa can evolve to decrease pyoverdine production51,52. However, because both pyoverdine producers and non-producers often co-exist within patients47,48, even if total pyoverdine production is reduced, pyoverdine non-producers or ‘cheaters’ could be protected by cooperators secreting pyoverdine.

During infections, both host and pathogen compete for scarce bioavailable iron53. P. aeruginosa has multiple iron acquisition systems: pyoverdine and pyochelin siderophores, host haem utilization and ferric citrate uptake systems. In cystic fibrosis airways, P. aeruginosa upregulates the expression of ferric citrate and haem uptake systems, while pyoverdine and pyochelin production are often downregulated52. However, we have shown that cefiderocol selects for pyoverdine hyper-producers. This finding raises concern that cefiderocol treatment might inadvertently select for hypervirulence because pyoverdine can directly damage host mitochondria and has been associated with disease severity in acute lung infection models54,55. Therefore, inhibiting pyoverdine production could both attenuate P. aeruginosa pathogenesis56 and potentiate cefiderocol.

Here, we extend the understanding of P. aeruginosa cefiderocol resistance by demonstrating how different nutritional cues select for distinct resistance variants. Cystic-fibrosis-mimicking conditions selected for cpxS variants which increased pyoverdine secretion and cross-protected susceptible cells and other members of polymicrobial communities. Considering the intraspecies and interspecies diversity in cystic fibrosis chronic infections, we expect that cefiderocol cross-protection could happen in vivo. Although these population social dynamics might negatively impact cefiderocol treatment, we demonstrated that fitness costs of cefiderocol resistance drive the dominance of susceptible cells in drug-free environments. Thus, fitness costs can theoretically be exploited to delay the emergence of cefiderocol resistance. Going forward, it will be important to explore whether cycling therapy can prevent cefiderocol resistance and suppress the emergence of cross-protector variants.

Methods

Strains, media and antibiotics

P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 was used for all cefiderocol resistance evolution experiments. SCFM2 was prepared as previously described23. SHU was prepared as previously described but without adding FeSO4 (ref. 57). Bacterial populations were grown at 37 °C in SCFM2 or SHU media as specified. Cefiderocol was obtained from MedChem Express. Purified pyoverdine and enterobactin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, and pyochelin I and II were obtained from Toronto Research Chemicals. The complete list of materials and sources is summarized in Supplementary Table 1. PAO1 Tn mutants were acquired from the Manoil laboratory (University of Washington)58. The identity of all PAO1 Tn mutants was confirmed using insertion-specific PCR before use.

Mutant construction

Variants of cpxS were generated via two-step homologous recombination as previously described59. The DNA fragments carrying the single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) for each cpxS variant (T163P, S227G and V235A) were generated with overlapping PCR reactions using the pairs of primers listed in Supplementary Table 3. The resulting fragments were each cloned into the suicide plasmid pEX18Gm, linearized with BamHI and EcorRI, using NEB Gibson Assembly Master Mix (New England BioLabs). P. aeruginosa strains were transformed by electroporation with the suicide plasmid carrying the cpxS variants and selected on LB with 30 µg ml−1 gentamicin. Clones in which double recombination events occurred were counter-selected on LB no-sodium sucrose plates. Mutants were confirmed by PCR and whole genome sequencing.

Experimental evolution

PAO1 was propagated for 10 days in SCFM2 and SHU conditions in preparation for the evolutionary experiment. The overnight cultures were diluted (1:100) into fresh medium without cefiderocol and grown overnight. This passaging step pre-adapted the lab strain PAO1 to the cystic-fibrosis- or UTI-like states and reduced the influence of adaptation to the host-mimicking media in the following comparisons29.

After 10 days of pre-adaptation, SCMF2- or SHU-adapted populations were sub-cultured into eight replicate populations that were propagated daily with increasing concentrations of cefiderocol. Each day, a twofold serial dilution of cefiderocol was freshly prepared in SCFM2 or SHU with concentrations ranging from 0.003 to 1,024 mg ml−1 cefiderocol, and 5 µl of aerobically grown overnight planktonic cultures was inoculated into each well. After overnight aerobic incubation at 37 °C in a cefiderocol-containing medium, cells from the highest concentration of cefiderocol which supported growth were collected. As before, 5 µl of this culture was reinoculated into aliquots of fresh cefiderocol-containing medium, and the remaining cells were frozen with 25% glycerol at −80 °C.

SCFM2-pre-adapted PAO1 was used to evolve cefiderocol resistance in SCFM2 aggregate populations. To mimic the oxygen and nutrient-limiting gradients that structured bacterial populations face during chronic cystic fibrosis infections, we used the agar biofilm block assay60. SCFM2-pre-adapted populations were grown overnight at 37 °C and 250 r.p.m. Cultures were diluted to OD600 (optical density at 600 nm) of 0.002 in molten SCFM2 with 0.5% noble agar, and 100 µl of the bacterial agar suspension was transferred to a 96-well plate containing 100 µl twofold serial dilutions spanning ten cefiderocol dilutions in SCFM2, including concentrations ranging from 0.003 to 1,024 mg ml−1 cefiderocol. After agar solidified at 25 °C, bacterial aggregates were transferred to a humidified chamber and incubated statically at 37 °C. After overnight growth, aggregates from the highest concentration of cefiderocol which supported growth were washed twice with PBS to wash away cells growing on the agar block surface. Then, aggregates were mechanically disrupted by vigorous pipetting with 100 µl PBS. Disrupted aggregates were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min and resuspended in 500 µl SCFM2. As described above, disrupted cells were diluted into molten SCFM2 agar and reinoculated into a new cefiderocol-containing molten SCFM2 agar to grow new aggregates. The remaining cells were frozen in SCFM2 with 25% glycerol.

Planktonic and biofilm populations were propagated with increasing drug concentrations until achieving growth at 1,024 µg ml−1 cefiderocol. In parallel, eight replicates of pre-adapted populations were passaged planktonically in SCFM2 and SHU and as aggregates in SCFM2 without any antibiotic as a control.

In addition to population analysis, we also identified mutations in 180 isolated colonies of SCFM2 evolved populations. We revived each of the eight cefiderocol-evolved and the ancestral SCFM2 pre-adapted populations from freezer stocks by streaking onto SCFM2 agar with 16 µg ml−1 cefiderocol. Evolved bacteria were grown 16 h at 37 °C, and from the streaked populations we randomly selected 20 clones each from the pre-adapted SCFM2 ancestor population and from the final evolved cefiderocol-resistant populations, for 180 total colonies. The isolated colonies were grown overnight in SCFM2 at 37 °C and 250 r.p.m. and processed accordingly for genotypic and phenotypic analyses.

Genome sequencing and analysis

DNA from control and evolved populations and evolved isolated clones (20 ancestor clones and 160 cefiderocol evolved clones) was extracted using the Qiagen DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen). Sequencing libraries were prepared using the Illumina DNA Prep kit (Illumina) and sequenced using an Illumina NovaSeq6000 at the Cedars-Sinai Cancer Applied Genomics Core. The variants were called using Breseq software package v0.31.0 using the default parameters and the -p flag for estimating the SNV polymorphism frequencies in populations using the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome as a reference61. After the variant calling, the variants detected in both control populations and in cefiderocol-evolved populations were manually removed from further consideration. In addition, synonymous variants and variants in intergenic regions were discarded. Mutations detected in at least 5% of any replicate were selected and summarized in Fig. 1c, and all mutations detected in cefiderocol-evolved populations, but not in control populations, are shown in Supplementary Table 6. The genetic diversity across evolved populations was estimated by calculating the Shannon index considering the presence and frequency of mutated genes. Shannon indices were calculated using vegan 2.6–4 R package62. P. aeruginosa clinical isolates (n = 113) were kindly provided by the Pulmonary Translational Research Core at the University of Pittsburgh. These isolates were sequenced by the Microbial Genome Sequencing Center, and indels and polymorphisms were called using Breseq as described above but using the consensus mode.

To analyse the relatedness among the cefiderocol-evolved isolated clones, we created a maximum parsimony phylogenetic tree based on the mutations detected with Breseq. The phylogenetic distances were estimated using the Phylip package with the comparison module of gdtools from Breseq. The phylogenetic trees were generated with iTOL v6 using PAO1 as the root63. We estimated the dN/dS ratio as the number of nonsynonymous mutations per nonsynonymous site (dN) to the number of synonymous mutations per synonymous site (dS). The total number of nonsynonymous and synonymous sites in the genome as well as the number of observed nonsynonymous mutations were calculated using the gdtools module of Breseq.

P. aeruginosa clinical isolate cefiderocol susceptibility testing and siderophore production

Cefiderocol resistance levels of P. aeruginosa clinical isolates (n = 113) were determined using cefiderocol MIC test strips (Liofilchem) placed onto cation-adjusted Muller–Hinton agar following the manufacturer’s instructions. Isolates’ cefiderocol susceptibility levels were classified following the US Food and Drug Administration breakpoints (sensitivity ≤1 µg ml−1, intermediate 2 µg ml−1, resistance ≥4 µg ml−1)30. It is noteworthy that the current Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoint for cefiderocol classifies P. aeruginosa as susceptible, intermediate and resistant isolates with MICs of ≤4, 8 and ≥16 µg ml−1, respectively64. Pairs of clinical isolates obtained from the same patient which presented with at least a 3.5-fold increase in cefiderocol MIC had their genomes analysed as described above, and mutations detected in paired clinical isolates analysed are shown in Supplementary Table 8.

Clinical isolates were grown on SCFM2 (initial inoculum at 105 CFU ml−1 (colony-forming units per millilitre)) overnight at 37 °C and 250 r.p.m. After that, 100 µl of bacterial culture was transferred to a 96-well plate, and the fluorescences of pyoverdine (excitation, 405 nm; emission, 460 nm) and pyochelin (excitation, 350 nm; emission, 430 nm) were measured using a Varioskan Lux Microplate Reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Siderophore production was normalized by bacterial cell density estimated by OD600.

Experimental evolution of cefiderocol-evolved population in drug-free media

To test fitness costs and the stability of cefiderocol resistance mutations, we propagated cefiderocol-resistant evolved populations daily in cefiderocol-free SCFM2 (planktonic or aggregates) and SHU for 14 days. Cefiderocol susceptibilities were determined daily using cefiderocol gradient strips. The genomic DNA was extracted from the final populations (evolved in drug-free environments for 14 days) and sequenced as described above.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of the control, cefiderocol-evolved and susceptibility-restored populations were determined by broth microdilution assays according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines, in which each bacterial isolate was tested in twofold-increasing concentrations of cefiderocol, CAZ, cefepime, ATM, tobramycin, colistin, polymyxin B and CIP. Cells were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and the lowest concentration of each antibiotic that inhibited bacterial growth, as determined by the absence of visible turbidity in each well, was considered the MIC. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed using cation-adjusted Muller–Hinton broth (CAMHB), except for cefiderocol MIC assays in which iron-depleted CAMHB was used. Iron-depleted CAMHB was prepared by adding 100 g of chelex-100 resin per litre of autoclaved CAMHB, and the suspension was stirred for 2 h at room temperature to remove cations in the medium. The depleted broth was filtered to remove the chelex resin and supplemented with 22.5 µg ml−1 CaCl2, 11.25 µg ml−1 MgCl2 and 0.56 µg ml−1 ZnSO4 (pH 7.2). Finally, the iron-depleted CAMHB was filter-sterilized and stored at room temperature.

RNA isolation and reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR

The expression of mexA and muxA were quantified by reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). The wild-type and cpxSSNV (T163P, S227G and V235A) strains were grown overnight in SCFM2, and the overnight cultures were sub-cultured in SCFM2 and incubated at 37 °C at 250 r.p.m. for 4 h. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini-Kit (Qiagen), and residual DNA was removed using a DNA-free DNA Removal Kit (Invitrogen). Complementary DNA was synthetized using SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix (Invitrogen). The qPCR reactions were carried out using the PowerUp SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems). Primers for RT-qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method with rpoD gene expression serving as the housekeeping transcription control.

In vitro competition assays

To compare relative fitness of cefiderocol-resistant populations, we performed in vitro competitions between ancestral and evolved final populations, tagged with mApple and eYFP fluorescent proteins, respectively. For competitions, each planktonic population was propagated from a freezer stock in appropriate conditions (media and cefiderocol concentration) for 24 h. Both ancestor and evolved populations were tagged by integrating mApple or eYFP genes at the att locus using the broad host-range mini-Tn7 vectors following the protocol described elsewhere65. Briefly, 1.5 ml of ancestral and cefiderocol-evolved populations grown overnight using appropriate conditions were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 3 min and washed twice with 300 mM sterile sucrose. Ancestral or cefiderocol-evolved populations were electroporated with 500 ng of pDB809 PrpsG::mApple or pUC18T-miniTn7T-Gm-PA1/04/03/eyfpT0T1, respectively, in combination with 500 ng of helper plasmid pTNS2. Transformants grown in the presence of 30 µg ml−1 gentamicin were pooled together for reconstituting the mixed populations. Overnight fluorescent cultures were diluted to OD600 of ~0.005 (~5 × 106 CFU ml−1) and mixed in a 1:1 ratio. After mixing ancestor and evolved populations, we inoculated 10 µl of mixed or single bacterial suspensions in 100 µl SCFM2 or SHU with or without 64 µg ml−1 cefiderocol in triplicate in a sterile 96-well plate. About 50 µl of mineral oil was added to each well to prevent evaporation. The plates were incubated for 20 h at 37 °C, shaking at 250 r.p.m., and the eYFP (excitation, 510 ± 5 nm; emission, 534 ± 5 nm) and mApple (excitation, 568 ± 5 nm; emission, 592 ± 5 nm) fluorescence was monitored hourly for 20 h using a Varioskan Lux Microplate Reader with the SkanIt software v5.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Planktonic competitive indices (CI) were calculated following equation (1):

| (1) |

For aggregate competition assays, cefiderocol-evolved aggregate populations were tagged with eYFP as described above. Overnight fluorescent cultures were diluted to OD600 of ~0.1 and mixed at 1:1 ratio. Then, 10 µl of mixed and single cultures were added and mixed into 1 ml SCFM2 with 0.5% noble agar for a final starting dilution of OD600 of 0.001. About 200 µl of the bacterial agar suspension was transferred into a well of an eight-well glass chamber slide for microscopy (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After overnight growth, aggregates from the highest concentration of cefiderocol which supported growth were washed twice with PBS to remove planktonic cells growing on the agar block surface. Aggregate populations were visualized with a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope in the Cedars-Sinai Microscopy Core Facility. About 500 µm z-stacks (50 slices total, 10 µm step size) were collected in 8 bit mode with a scan format of 512 × 512 pixels60. Zeiss Zen v3.3 software was used for image collection. Aggregate volume was quantified using Imaris 9.9 (Oxford Instruments) using the surfaces function in Imaris based on the mApple or eYFP signals in each z-stack as previously described66. Aggregate CI was calculated following the equation (2):

| (2) |

RNA-seq analyses

RNA-seq analysis was performed to measure global gene expression in the ancestor and evolved planktonic populations grown in co-culture. Ancestral populations were co-cultured in competition with each evolved population in SCFM2 with 64 µg ml−1 cefiderocol as described above. After 8 h of competition, cells were collected, and the RNA was extracted using a RNeasy mini Kit (Qiagen). Residual DNA was removed using a DNA-free DNA Removal Kit (Invitrogen). Ribosomal RNA was depleted with the Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit (Illumina). RNA-seq libraries were prepared using the Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep kit (Illumina) and sequenced using an Illumina NovaSeq6000 at the Cedars-Sinai Cancer Applied Genomics Core targeting 30 million reads per sample.

RNA-seq reads were analysed using CLC Genomics workbench 22.01 (Qiagen). The P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome and annotations were downloaded from the Pseudomonas Genome Database and used as a reference for analyses. Reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM) values were generated using default parameters. Fold changes in gene expression and statistical analyses were performed using an Extraction of Differential Gene Expression test with the Bonferroni correction.

Chelating activity

Chelating activity of cefiderocol and bacterial siderophores (pyochelin, pyoverdine and enterobactin) were measured by the chrome azurol B colorimetric assay67. About 100 µl of cefiderocol and siderophores (0.1 to 500 µM) were mixed with CAS shuttle solution (0.5 mM anhydrous piperazine, pH 5.5, containing 1 mM chrome azurol B, 5 mM ethyltrimethylammonium bromide and 4 µM FeCl3) and incubated for 30 min at 25 °C. The colour changes of the solutions were detected by measuring the OD630nm using Varioskan Lux Microplate Reader.

Cefiderocol iron displacement

Initially, 100 µM iron-free cefiderocol was incubated with 100 µM of FeCl3 overnight to obtain ferric cefiderocol. Ferric cefiderocol was then incubated with equimolar amounts of iron-free pyoverdine for 1 h at room temperature. Cefiderocol iron displacement by pyoverdine was estimated by fluorescence quenching due to iron–pyoverdine complex formation and was monitored with a Varioskan Lux Microplate Reader by measuring the emission wavelength spectra (excitation, 405 nm; emission, range 420–600 nm).

Interspecies competition

For interspecies competitions, K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883, E. coli ATCC 25922 and cpxS SNV mutants were tagged by integrating mApple or eYFP at the att locus using the broad host-range mini-Tn7 vectors, as described above. Overnight fluorescent cultures were diluted to OD600 of ~0.005 (~5 × 106 CFU ml−1) and mixed in a 1:1 ratio. For competitions, each planktonic population was propagated from a freezer stock in appropriate conditions (media and cefiderocol concentration) for 24 h. Overnight fluorescent cultures were diluted to OD600 of ~0.005 (~5 × 106 CFU ml−1) and mixed in a 1:1 ratio. About 10 µl of dual or single bacterial species suspensions were grown in 100 µl SCFM2 with or without 0.25 µg ml−1 cefiderocol in triplicate in a sterile 96-well plate. About 50 µl of mineral oil was added to each well to prevent evaporation. The plates were incubated for 20 h at 37 °C, shaking at 250 r.p.m., and the growth of K. pneumoniae and E. coli was measured by monitoring the eYFP fluorescence (excitation, 510 ± 5 nm; emission, 534 ± 5 nm), while the growth of P. aeruginosa variants was measured by mApple fluorescence (excitation, 568 ± 5 nm; emission, 592 ± 5 nm). Fluorescence was monitored using Varioskan Lux Microplate Reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

To further explore the effect of pyoverdine on cross-protection, we selected two P. aeruginosa clinical isolates (121a—low pyoverdine producer—and 172aC—high pyoverdine producer) for interspecies competitions. Overnight cultures were adjusted to OD600 of ~0.005, and dual and single bacterial suspensions were inoculated in 500 µl of SCFM2 with or without 0.5 µg ml−1 cefiderocol at ~5 × 105 CFU ml−1. Competition assays were grown for 24 h at 37 °C and 250 r.p.m. After competitions, samples were serial diluted, and CFUs were counted on selective media. P. aeruginosa was selected on Pseudomonas isolation agar, and K. pneumoniae or E. coli was selected on LB supplemented with cefsulodin 25 µg ml−1. After 24 h competition, 100 µl of bacterial culture was transferred to a 96-well plate, and pyoverdine fluorescence (excitation, 405 nm; emission, 460 nm) was measured using a Varioskan Lux Microplate Reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Pyoverdine production was normalized by bacterial growth (OD600).

Statistics

Evolution experiments were performed using eight parallel cultures. All other experiments were performed using at least three biological replicates, and data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to evaluate whether the data met the assumptions of normality of variance. Significance between two unpaired groups was assessed using a two-sample Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney test, based on sample distributions. For comparing three or more groups, a one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test and Kruskal–Wallis or Dunnett’s multiple comparisons tests, was performed for parametric and non-parametric analyses. All testing was considered significant at the two-tailed P < 0.05. Analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism v9.5.1. The P values are listed in Supplementary Table 10.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Time to achieve growth at high cefiderocol concentrations during experimental evolution.

Mean time to achieve growth at (a) 4 µg/ml and (b) 1,024 µg/ml cefiderocol during experimental evolution in cystic fibrosis (SCFM2 planktonic and aggregate populations) and synthetic human urine (SHU) media (Mean ± SD; p-values: one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, n = 8 parallel cultures).

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Genetic diversity of populations evolved in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations of cefiderocol.

Shannon diversity indices were calculated from SNV frequencies in control populations passaged in cefiderocol-free media and in cefiderocol-evolved populations (mean; p-values, two-sided unpaired t-test, n = 8 parallel cultures).

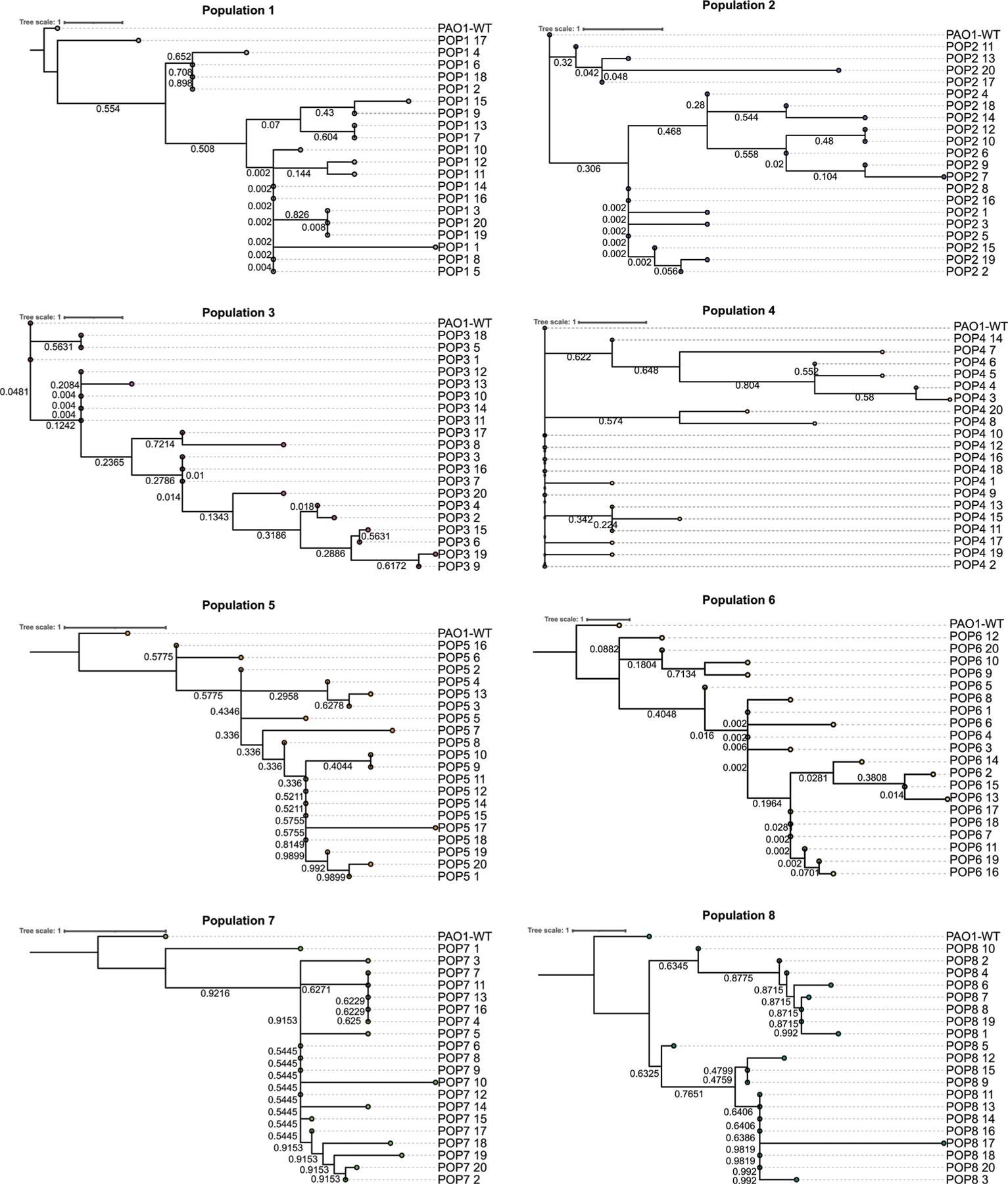

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Maximum parsimony phylogenetic trees of evolved isolates show diversity within each cefiderocol resistant population.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic trees were constructed based on mutations detected in cefiderocol evolved isolated colonies (20 colonies per evolved population). Phylogenetic trees were rooted on the PAO1 wild-type genome. Bootstrap values are indicated on respective branches. Trees were plotted using iTOL.

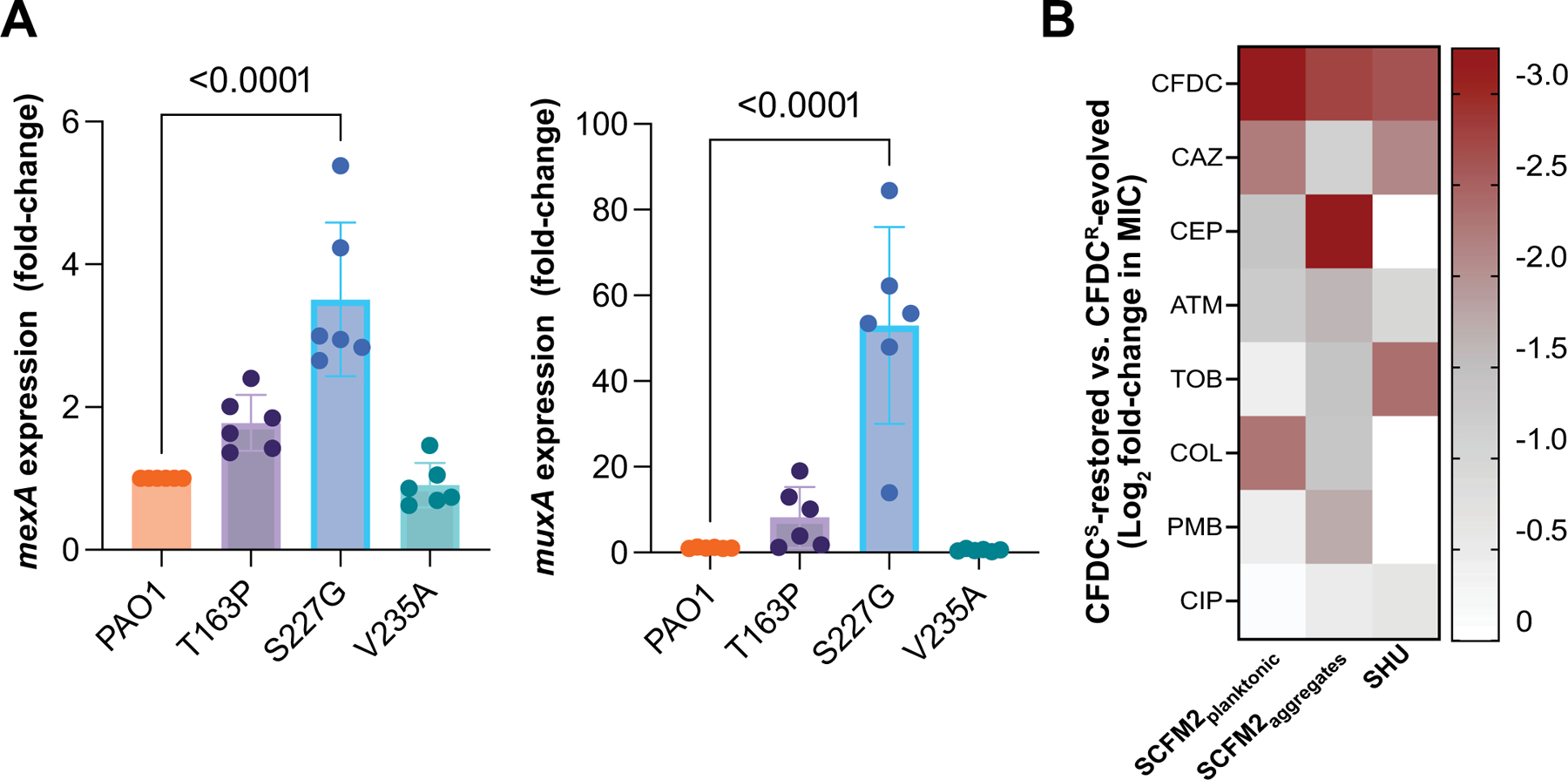

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Increased efflux pump gene expression in cpxS variants and decreased antibiotic cross-resistance after drug-free selection.

a, Expression of mexA and muxA genes known to be under the control of the CPX two-component system, by RT-qPCR in PAO1 wild-type and cpxSSNV variants (T163P, S227G, and S235A) (mean ± SEM, ANOVA Dunnett′s multiple comparisons test, n = 6 independent experiments). b, Heatmap of antimicrobial susceptibilities of populations evolved in the absence of cefiderocol for 15 d. Heatmap indicates the mean log2 MIC fold change of drug-free-passaged populations compared to cefiderocol resistant populations (n = 8 populations per growth condition). CFDC, cefiderocol; CAZ, ceftazidime; CEP, cefepime, ATM, aztreonam, TOB, tobramycin, COL, colistin, PMB, polymyxin B, CIP ciprofloxacin.

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. In vitro competitions between ancestral and cefiderocol-resistant evolved populations.

a, Planktonic competitions between ancestral and cefiderocol-resistant evolved populations in SCFM2 and SHU. b, Biofilm competitions between ancestral and cefiderocol-resistant evolved populations in SCFM2 with (right) or without (left) cefiderocol. Evolved and ancestral populations were tagged with eYFP and mApple fluorescent proteins, respectively. The fluorescent populations were competed (1:1 ratios) in the presence or absence of cefiderocol (64 µg/ml). Planktonic populations growth was determined by monitoring fluorescence over time (h). Experiments were performed in triplicate, in three independent experimental sets (mean ± SD n = 3 independent experiments). Biofilm competitions were visualized by confocal microscopy.

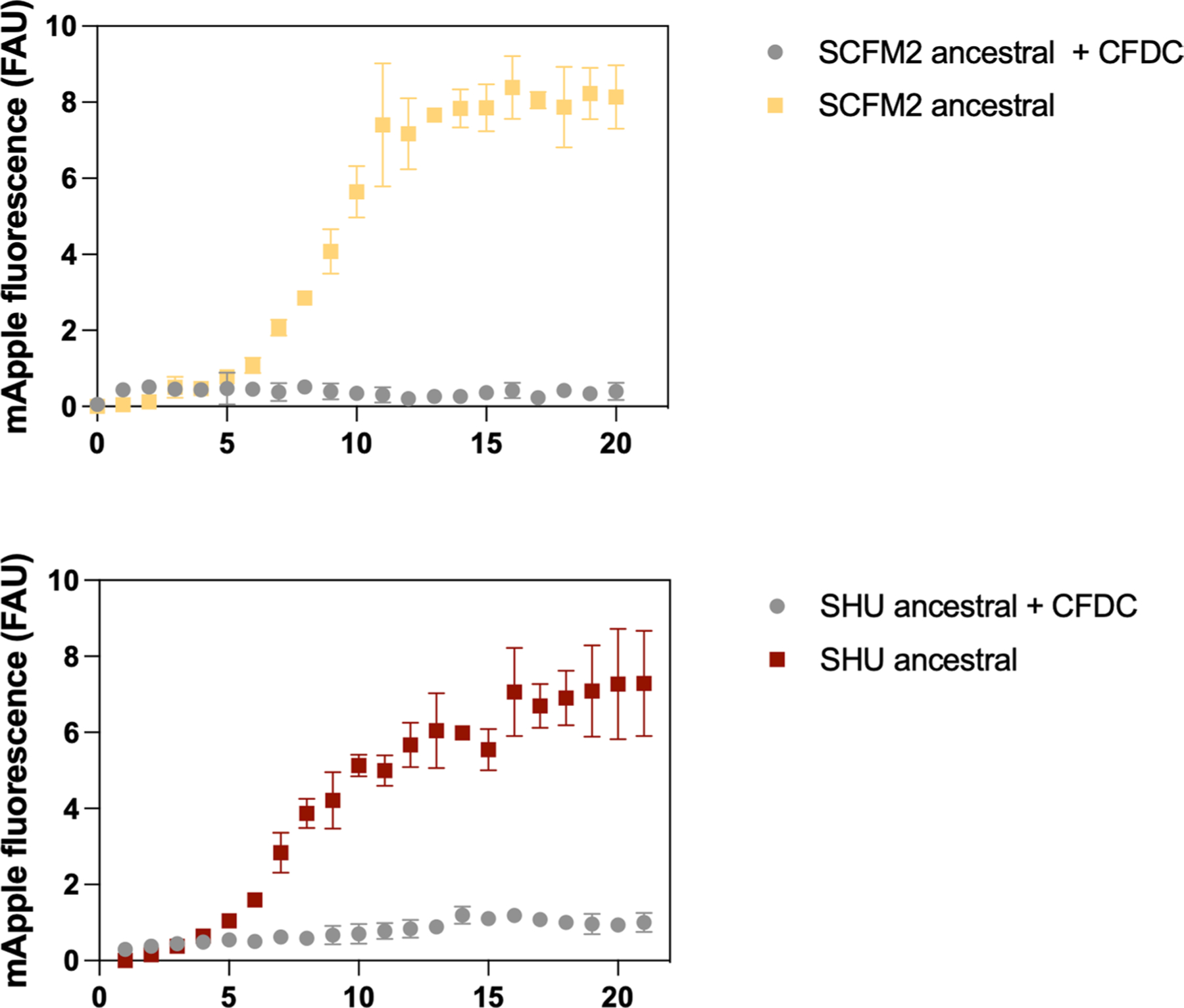

Extended Data Fig. 6 |. Ancestral populations are unable to grow in the presence of cefiderocol.

Growth in the presence and absence of 64 µg/ml cefiderocol of pre-adapted populations was determined by monitoring fluorescence over time (h). Experiments were performed in triplicate, in three independent experimental sets (mean ± SD n = 3 independent experiments).

Extended Data Fig. 7 |. Production of pyoverdine and pyochelin and cefiderocol susceptibilities of evolved isolated colonies.

Pyoverdine and pyochelin production by evolved isolated colonies in relation to cefiderocol susceptibility (Two-sided Spearman correlation, n = 160).

Extended Data Fig. 8 |. Bacterial siderophores confer cefiderocol cross-protection.

a, Ferric iron chelating activity of cefiderocol and bacterial siderophores. The chelating activity was detected by the colorimetric changes of chrome azurol B (OD630nm) at different chelator concentrations (0, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100 and 250 µM) (mean ± SEM, ANOVA, n = 2 independent experiments). b, Enterobactin protects K. pneumoniae (Kp), E. coli (Ec), B. cenocepacia (Bc), and B. multivorans (Bm) from cefiderocol killing in a dose-dependent manner. The combinatorial effect of enterobactin with cefiderocol is expressed by the log2 cefiderocol fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC; n = 3 independent experiments, mean ± SD). c, Planktonic competitions between P. aeruginosa (PAO1::mApple or cpxSS227G::mApple) and K. pneumoniae (ATCC 13883::eYFP – left) or E. coli (ATCC 25922::eYFP – right) in the presence of inhibitory concentrations with or without additional pyoverdine (8 µg/ml). The growth of K. pneumoniae and E. coli was measured by eYFP fluorescence area under the curve (AUC) (mean ± SEM, ANOVA, Dunnett′s multiple comparisons test, n = 5 independent experiments). d, Pyoverdine production by P. aeruginosa lab strains and clinical isolates in SCFM2 (mean ± SEM, ANOVA, Tukey′s multiple comparisons test, n = 3 independent experiments).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by grant numbers JORTH17F5, JORTH19P0 and MILESI21F0 from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and grant numbers K22AI127473, R21AI151362 and R01AI14642 from the NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and R01Hl136143 from the NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. We thank Applied Genomics, Computation and Translational Core at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, for helping with whole-genome sequencing and bulk RNA sequencing. We also thank the Pulmonary Translational Research Core team at the University of Pittsburgh for the P. aeruginosa clinical isolates used in this study.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Extended data is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01601-4.

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01601-4.

Peer review information Nature Microbiology thanks James Gurney and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

RNA, whole-genome population and colony sequencing data are accessible in the NCBI SRA under accession number PRJNA971207. Genome sequencing data for the clinical isolates are available in the NCBI SRA under the accession number PRJNA934930. Confocal micrographs are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24898107. The reference genome sequence of P. aeruginosa PAO1 is available from GenBank, with accession number NC_002516. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

- 1.Huemer M, Mairpady Shambat S, Brugger SD & Zinkernagel AS Antibiotic resistance and persistence—implications for human health and treatment perspectives. EMBO Rep 21, e51034 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tacconelli E et al. Surveillance for control of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis 18, e99–e106 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nathwani D, Raman G, Sulham K, Gavaghan M & Menon V Clinical and economic consequences of hospital-acquired resistant and multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 3, 32 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mittal R, Aggarwal S, Sharma S, Chhibber S & Harjai K Urinary tract infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a minireview. J. Infect. Public Health 2, 101–111 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreiro JLL et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa urinary tract infections in hospitalized patients: mortality and prognostic factors. PLoS ONE 12, e0178178 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry—2020 Annual Data Report (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aoki T et al. Cefiderocol (S-649266), a new siderophore cephalosporin exhibiting potent activities against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Gram-negative pathogens including multi-drug resistant bacteria: structure activity relationship. Eur. J. Med. Chem 155, 847–868 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moynié L et al. Structure and function of the PiuA and PirA siderophore–drug receptors from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e02531–16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito A et al. Siderophore cephalosporin cefiderocol utilizes ferric iron transporter systems for antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 7396–7401 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luscher A et al. TonB-dependent receptor repertoire of Pseudomonas aeruginosa for uptake of siderophore–drug conjugates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 62, e00097–18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito A et al. In vitro antibacterial properties of cefiderocol, a novel siderophore cephalosporin, against Gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 62, e01454–17 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito A et al. 696. Mechanism of cefiderocol high MIC mutants obtained in non-clinical FoR studies. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 5, S251 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Courvalin P Why is antibiotic resistance a deadly emerging disease? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 22, 405–407 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Streling AP et al. Evolution of cefiderocol non-susceptibility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a patient without previous exposure to the antibiotic. Clin. Infect. Dis. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1909 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamma PD et al. Comparing the activity of novel antibiotic agents against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales clinical isolates. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 10.1017/ice.2022.161 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simner PJ et al. Cefiderocol activity against clinical Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates exhibiting ceftolozane–tazobactam resistance. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 8, ofab311 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ikawa S, Yamasaki S, Morita Y & Nishino K Role of the drug efflux pump in the intrinsic cefiderocol resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/2022.05.31.494263 (2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomis-Font MA, Sastre-Femenia MÀ, Taltavull B, Cabot G & Oliver A In vitro dynamics and mechanisms of cefiderocol resistance development in wild-type, mutator and XDR Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 78, 1785–1794 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan DCK et al. Nutrient limitation sensitizes Pseudomonas aeruginosa to vancomycin. ACS Infect. Dis. 9, 1408–1423 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nordmann P et al. Mechanisms of reduced susceptibility to cefiderocol among isolates from the CREDIBLE-CR and APEKS-NP clinical trials. Microb. Drug Resist. 28, 398–407 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schick A & Kassen R Rapid diversification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung-like conditions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 10714–10719 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tingpej P et al. Phenotypic characterization of clonal and nonclonal Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from lungs of adults with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 1697–1704 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]