Abstract

Objective

Myocardial crypts are congenital abnormalities associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) and other conditions. This study assessed the prevalence of myocardial crypts in Japanese patients.

Methods

Myocardial crypts were evaluated in a consecutive series of 300 patients (13-92 years old) who underwent computed tomography angiography (CTA) because of clinical suspicion of ischemic heart disease.

Results

We found a myocardial crypt incidence of 9.7% (29 patients) in our study population, with multiple crypts observed in 2.3% (7 patients). Among these, myocardial crypts were found in 2 out of 8 (25%) patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), 1 of which was apical-type HCM. In patients with a single crypt (22 patients), the most common location of the crypt was at the left ventricular apex (16/22 patients, 72.7%), followed by the inferior wall (5/22 patients, 22.7%) and the interventricular septum (1/22 patients, 4.6%).

Conclusion

The incidence of myocardial crypts observed in our study aligns with that reported in previous studies, although the most common location among the Japanese population was the left ventricular apex.

Keywords: computed tomography, crypt, congenital abnormality

Introduction

Myocardial crypts, also referred to as clefts, are congenital abnormalities related to myocardial fibers or fascicle disarray. They were initially identified during autopsies of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) (1-3), but later studies reported their presence in healthy volunteers and patients with HCM in vivo, as detected by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) (4,5). A myocardial crypt can be characterized as a discrete V-shaped fissure confined within the myocardium that tends to narrow or become occluded during systole without local hypokinesia or dyskinesia (5).

The prevalence, location, and clinical significance of these crypts have varied among reports (4-15). However, thus far, there have been no reports on myocardial crypts in the Japanese population.

High-resolution cardiac computed tomography (CT) and CMRI allow for the diagnosis of congenital ventricular outpouchings, including clefts and crypts (16). We therefore assessed the prevalence of myocardial crypts in Japanese patients using cardiac CT.

Materials and Methods

Study population

Over a 13-month period from April 2019 to May 2020, we evaluated left ventricular (LV) crypts in 300 consecutive patients (13-92 years old) who underwent cardiac CT for suspected ischemic heart disease or a preoperative evaluation for transcatheter aortic valve replacement in our department. We also assessed the number and location of the crypts.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nagasaki University Hospital and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (approval number: 20091407).

Crypt definition

A myocardial crypt was defined as an abrupt, sharp-edged disruption of normally compacted myocardium penetrating more than 50% of the myocardial wall and exhibiting total or near-total obliteration during systole due to surrounding tissue. We distinguished recesses associated with hypertrabeculation from crypt and excluded it (17).

Cardiac CT

We used a 128-section dual-source CT system (Somatom Definition Flash; Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany) to perform coronary CT angiography (CTA) utilizing a retrospective electrocardiogram (ECG)-synchronized helical mode with tube current modulation. The dual-source CT parameters were as follows: collimation, 2×64.0×0.6 mm; pitch of 3.2 for heart rate-adapted pitch for standard retrospective ECG-synchronized coronary CTA; reference tube current-time product, 320 mAs per rotation; tube potential, 100 kVp or 120 kVp according to the patient's body weight (≤60 kg, 100 kVp; >60 kg, 120 kVp); gantry rotation time, 280 msec; and temporal resolution, 75 msec.

Nitroglycerin (0.6 mg) was administered sublingually to patients with systolic blood pressure greater than 100 mmHg in the CT examination room. If a patient had a heart rate above 80 beats/min, a β-blocker (landiolol, 0.125 mg/kg) was administered intravenously within a minute. A dual-head power injector (Nemoto; Nemoto Kyorindo, Tokyo, Japan) was used to administer nonionic contrast material (iopromide, 370 mg of iodine per mL, Ultravist; Bayer Healthcare, Berlin, Germany) at a rate of 3.5-5 mL/s (range, 50-70 mL), followed by 30 mL of saline at the same rate. The peak enhancement time was determined by performing dynamic scanning at the ascending aorta level using 10 mL of contrast material injected at a rate of 3.5-5 mL/s, and an additional delay of 5 s was added to the time to peak enhancement before image acquisition. In retrospective ECG-synchronized helical coronary CTA, the scan coverage ranges from the carina level to the diaphragm. For patients with heart rates of 70 beats/min or less, full tube current was applied at 70-80% of the R-R interval, and for those with heart rates above 70 beats/min, full tube current was applied 200-400 ms after the R peak. For the rest of the R-R interval, a reduced dose (4% of the dose during the acquisition window) was used to minimize radiation exposure.

The transverse images were reconstructed with a section thickness of 0.8 mm and an image matrix of 512×512 pixels, using medium-soft (B26f) and sharp (B46f) tissue convolution kernels. A display field of 26 cm, corresponding to a pixel size of approximately 0.5 mm2, was deemed adequate. To minimize inter-observer variability, 2 expert reviewers, blinded to the patient data, independently confirmed the presence of crypts, achieving a 92% inter-observer agreement rate for crypt identification.

Continuous and categorical variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation and percentages, respectively. Continuous variables were compared using Student's t-test or Wilcoxon's test, as appropriate, while categorical variables were compared using χ2 statistics or Fisher's exact test.

Statistical analyses were performed using the JMP statistical software program (JMP PRO 17; SAS Institute, Cary, USA). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

In our study population, ischemic heart disease (115 patients, 38.3%) was most common, followed by aortic disease (45 patients, 15%), and aortic valve stenosis (27 patients, 9%). In addition, 8 patients (2.7%) were diagnosed with HCM (Table 1). The overall incidence of LV crypts was 9.7% (29 patients), with multiple crypts (ranging from 2 to 4 crypts) seen in 2.3% (7 patients) of our study population. Therefore, among patients with LV crypts, 75.9% had a single crypt, and 24.1% had multiple crypts. Two out of the 8 patients with HCM (25%), 1 of whom had apical-type HCM, had crypts (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics.

| All | |

|---|---|

| n | 300 |

| Age (years) | 68.6±14.1 |

| Male, n (%) | 197 (65.7) |

| Height (cm) | 161.1±9.76 |

| Weight (kg) | 59.5±14.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.7±4.16 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 65 (21.7) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 164 (54.7) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 96 (32.0) |

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 115 (38.3) |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 55 (18.3) |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 48 (16.0) |

| Aortic disease, n (%) | 45 (15.0) |

| Aortic valve stenosis, n (%) | 27 (9.0) |

| Conduction disturbance, n (%) | 9 (3.0) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 53 (17.7) |

| Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 15 (5.0) |

| HCM, n (%) | 8 (2.7) |

| Other cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 7 (2.3) |

| Congenital heart disease, n (%) | 3 (1.0) |

Values presented as n (%) or ±SD. BMI: body mass index, CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting, HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Table 2.

Number of Patients with Crypts and Location of Crypts.

| Crypt+ | |

|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | 29/300 (9.7) |

| Single, n (%) | 22/300 (7.3) |

| Multiple, n (%) | 7/300 (2.3) |

| Location of crypts, n (%) (39 in 29 cases) | LV apex 19 (49), inferior wall of LV 9 (23), IVS 11 (28) |

| Crypts by cardiovascular disease*1 | Crypt+ |

| Location of crypts, n (%) | |

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 11/115 (9.6) |

| 13 crypts [LV apex 9 (69), inferior wall of LV 2 (15), IVS 2 (15)] | |

| Aortic disease, n (%) | 3/45 (6.7) |

| 4 crypts [LV apex 3 (75), inferior wall of LV 1 (25)] | |

| Aortic valve stenosis, n (%) | 1/27 (3.7) |

| 1 crypt [LV apex 1 (100)] | |

| Conduction disturbance, n (%) | 2/9 (22.2) |

| 3 crypts [inferior wall of LV 1 (33), IVS 2 (67)] | |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 5/48 (10.4) |

| 7 crypts [LV apex 3 (43), inferior wall of LV 4 (57)] | |

| HCM, n (%) | 2/8 (25.0) |

| 2 crypts [LV apex 2 (100)] | |

| Other cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 1/7 (14.3) |

| 1 crypt [LV apex 1 (100)] | |

| Congenital heart disease, n (%) | 0/3 (0) |

| Other diseases, n (%) | 8/85 (9.4) |

| 14 crypts [LV apex 3 (21), inferior wall of LV 4 (29), IVS 7 (50)] |

HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, IVS: interventricular septum, LV apex: left ventricular apex, LV: left ventricle, *1: There are disease overlaps in 4 cases with crypts (ischemic heart disease and atrial fibrillation in 2 cases, aortic disease and atrial fibrillation in one case, and ischemic heart disease and conduction disturbance in one case)

The prevalence of crypts was 9.6% (11/115) among ischemic heart disease cases, 7.2% (3/45) among aortic disease cases, and 3.7% (1/27) among aortic valve stenosis cases. Among the 22 patients with a single crypt, the most common location was the LV apex (16/22 patients, 72.7%), followed by the inferior wall (5/22 patients, 22.7%) and the interventricular septum (IVS) (1/22 patients, 4.6%) (Table 2).

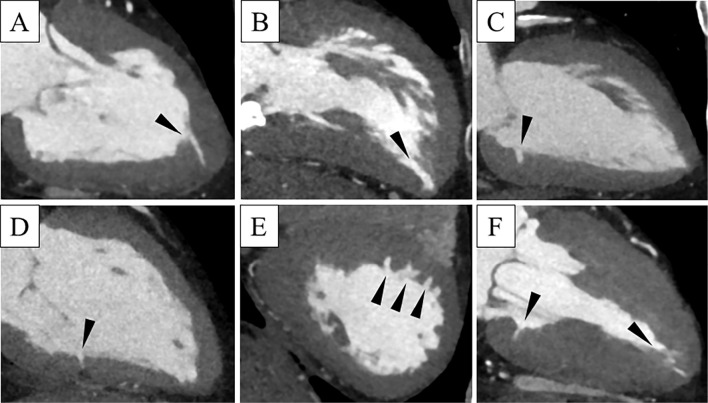

The multiple crypts in the seven patients were distributed as follows (one patient each): all four crypts in the IVS, all three in the IVS, both in the IVS, both in the inferior wall of the LV, both crypts in the inferior wall of the LV, one in the apex and one in the inferior wall of the LV, and one in the LV apex and one in the IVS. Therefore, 16 patients (5.3%) had only apical crypts, while 13 (4.3%) had crypts located elsewhere in the sample of 300 patients (Figure).

Figure.

Examples of crypts located in different segments of the left ventricle by cardiac computed tomography. In patients with a single crypt (arrowheads), crypts can be observed at the apex (A, B) and the inferior wall (C, D). In patients with multiple crypts (arrowheads), they can be observed in the interventricular septum (E) and inferior wall and apex (F).

In this study, the prevalence of LV crypts in patients with HCM was 25% (2/8). Patients with crypts had a larger body mass index (BMI) than those without crypts, although there was no significant difference in patient characteristics between those with and without crypts (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison between Crypt (-) and Crypt (+).

| Crypt- | Crypt+ | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | 271 (90.3) | 29 (9.7) | |

| Age (years) | 69.0±13.7 | 65.1±17.4 | 0.26 |

| Male, n (%) | 178 (65.7) | 19 (65.5) | 0.99 |

| Height (cm) | 161.0±9.83 | 162.0±9.15 | 0.59 |

| Weight (kg) | 58.9±14.3 | 66.5±3.89 | 0.07 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.5±4.03 | 25.0±5.04 | 0.03 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 55 (20.3) | 10 (34.5) | 0.09 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 144 (53.1) | 20 (69.0) | 0.10 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 82 (30.3) | 14 (48.3) | 0.06 |

| Ischemic heart disease, n (%) | 104 (38.4) | 11 (37.9) | 0.96 |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 48 (17.7) | 7 (24.1) | 0.41 |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 45 (16.6) | 3 (10.3) | 0.36 |

| Aortic disease, n (%) | 42 (15.5) | 3 (10.3) | 0.44 |

| Aortic valve stenosis, n (%) | 26 (9.6) | 1 (3.5) | 0.22 |

| Conduction disturbance, n (%) | 7 (2.6) | 2 (6.9) | 0.26 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 48 (17.7) | 5 (17.2) | 0.95 |

| Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 12 (4.4) | 3 (10.3) | 0.21 |

| HCM, n (%) | 6 (2.2) | 2 (6.9) | 0.20 |

| Other cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 6 (2.2) | 1 (3.5) | 0.69 |

| Congenital heart disease, n (%) | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0.43 |

Values presented as n (%) or±SD. BMI: body mass index, CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting, HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

Discussion

The present study examined the prevalence of myocardial crypts in Japanese patients using coronary CTA. We found 28 reports on the left ventricle and crypt; however, we excluded case reports and ultimately reviewed 11 studies on LV crypts using CMRI and CTA (Table 4) (5-10,12,13,17-19). These studies indicated a crypt incidence range of 6.3 to 33%. Four of them, focusing on HCM patients or patients carrying an HCM mutation, showed a high crypt prevalence from 9.6% to 33% (10,17-19). Excluding these four studies, the crypt prevalence ranged from 6.3% to 9.4%. Furthermore, the crypt prevalence in previous CTA studies (6.7-9.4%) was higher than that in MRI studies (6.3-7.4%) (Table 4). The prevalence rates in our study (total, 9.7%; multiple, 2.3%) were almost identical to those of Sigvardsen's study using CTA (total, 9.1%; multiple, 2.1%) (12).

Table 4.

List of Previous References of Crypts.

| Diagnostic study | Total No. | Crypt+ (%) | Object No. | Age | Crypt+ (%) by object | Multiple/crypt+ (%) | Popular location | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | 300 | 9.7 | *1300 | 68.6 | § | 24.1 | Apex septum inferior | Ours | |

| CT | 2,093 | 6.7 | *12093 | 55 | NA | 34.8 | Inferoseptum | (9) | |

| CT | 393 | 9.4 | HCM 73 | 49.4 | 24.7 | 39 | Septum | (13) | |

| HT 100 | 58.4 | 7 | NA | Septum | |||||

| AS 120 | 75.6 | 6.7 | NA | Septum | |||||

| Healthy 100 | 56.9 | 4 | 0 | Septum | |||||

| CT | 10,097 | 9.1 | *210097 | 60.3 | NA | 23.5 | Insertion point of RV | (12) | |

| MRI | 399 | Inferior | Septum | (5) | |||||

| NA | Healthy 120 | NA | 5.8 | 5 | 14 | Inferior septum | |||

| HCM 91 | NA | 5.5 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| HT 44 | NA | 11.4 | 0 | NA | |||||

| rTOF 104 | NA | 0.97 | 12.5 | NA | |||||

| rPS 40 | NA | 22.5 | 12.5 | NA | |||||

| MRI | 310 | 20 | Carrier 43 | 40 | 69.8 | 70 | Inferior | (10) | |

| *1252 | 52 | 12.3 | 5 | ||||||

| *315 | NA | 6.7 | NA | ||||||

| MRI | 390 | 7.4 | Carrier 31 | 28 | 61.3 | 58 | Septum posterior | (6) | |

| HCM 261 | 46 | 3.8 | NA | ||||||

| Healthy 98 | NA | 0 | NA | ||||||

| MRI | 1,020 | 6.3 | *1306 | 44.7 | 3.6 | NA | Inferior | (8) | |

| ICM 236 | 65.3 | 5.1 | NA | ||||||

| NICM 373 | 54.5 | 6.4 | NA | ||||||

| Family 43 | 42.4 | 23 | NA | ||||||

| Other 62 | 48.7 | 11 | NA | ||||||

| MRI | 686 | 6.7 | *1686 | 48 | NA | 8.7 | Inferior | (7) | |

| MRI | 146 | 18 | Carrier 73 | 29 | 33 | 58 | NA | (17) | |

| Healthy 73 | 30 | 3 | 0 | ||||||

| MRI | 94 | 9.6 | HCM 94 | 52 | NA | NA | NA | (18) | |

| MRI | 97 | 33 | Carrier 57 | 45 | 47.4 | 16 | NA | (19) | |

| Healthy 40 | 45 | 12.5 | 0 | ||||||

HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, HT: hypertension, AS: aortic valve stenosis, rTOF: repaired tetralogy of fallot, rPS: repaired pulmonary valve stenosis, Carrier: HCM mutation carriers without LV hypertrophy, *1: patients examined for any reason, *2: randomly selected individuals in the cohort, *3: carrier family without no mutation, §: unable to evaluate due to overlap of diseases, NA: not available

These findings suggest that crypt prevalence may be influenced by heart disease, particularly HCM, and the imaging modalities used for the crypt evaluation. We also demonstrated that crypts were most commonly seen in the LV apex, followed by the inferior wall of the left ventricle and IVS, contradicting previous reports that identified the inferior wall of the left ventricle or IVS as the most common crypt locations (4-15).

Previous research has indicated that congenital LV diverticulum, a rare cardiac anomaly, is often located at the LV apex (20). However, only two reports mentioned crypts in the LV apex (9,13). Erol et al. (9) reported crypts at the apical septal segment in 2.1% and at the apex in 1.4% of cases. Arow et al. (13) found crypts in the LV apex in 8.3% of patients with aortic stenosis, 10% with hypertension, and 24% with HCM. However, the crypts were mostly located in the LV septum, and the prevalence of crypts in the LV apex was not discussed among their patients.

Several studies have highlighted the increased prevalence of crypts in HCM (4,10,13,14,19). Furthermore, in HCM mutation carriers without hypertrophy, crypts can be detected even when echocardiography and ECG findings appear normal (4). Previous studies showed a higher prevalence of crypts in HCM patients (24.7% according to previous CT studies and 5.4% according to previous MRI studies) than in healthy volunteers (or normal subjects) (4% according to previous CT studies and 3.3% according to previous MRI studies) or patients with other diseases (Table 5) (6-10,12,13,17-19).

Table 5.

Prevalence of Crypts by Category in Our and Previous CT or Previous MRI Studies.

| Our study (CT) | Previous CT studies | Previous MRI studies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCM, n (%) | 2/8 (25.0) | 18/73 (24.7) | 19/355 (5.4) |

| Healthy volunteers or normal subjects, n (%) | NA | 4/100 (4.0) | 7/211 (3.3) |

| Other diseases, n (%) | 27/292 (9.2) | 15/220 (6.8) | 19/298 (6.4) |

In line with these previous studies, we found a similar prevalence of crypts in HCM patients in the present study (Table 5). However, our study had a limited number of HCM cases, and we did not conduct genetic testing for HCM. Apical HCM, first described in Japanese patients (21,22), accounts for 25% of all HCM cases in Japan, while in non-Japanese populations, it represents only 1% to 2% of cases (15). Therefore, apical HCM and its carriers without apical hypertrophy may be linked to apical crypts. However, only one case of apical HCM had a crypt at the apex, and we did not conduct a gene test for HCM.

Erol et al. (9) noted that LV crypts are oriented approximately perpendicular to the left ventricle long axis and are commonly found in the IVS and inferior wall of the left ventricle, with the apical segments of the septum and ventricular apex being rare. Several previous reports (8,9,13,17) included a perpendicular orientation to the left ventricle long axis in their crypt definition, whereas others did not (5-7,10,12,18,19).

In our study, crypts that were not located at the apex were perpendicular to the left ventricle long axis; however, many apical crypts did not follow this pattern. This suggests that apical crypts may have different characteristics from crypts in other areas. Previous studies have reported LV apical thinning as a normal anatomical variation that is distinct from the LV crypt (23,24). However, there may be some overlap, requiring further research to assess the prevalence and location of LV crypts, particularly at the LV apex.

Our study also demonstrated that the BMI of patients with crypts was higher than that of patients without crypts. This contrasts with the findings of Sigvardson et al. (12) who reported that advanced age, hypertension, and a high BMI are associated with fewer myocardial crypts. Arow et al. (13) found no significant difference in the BMI between patients with and without crypts. Therefore, further studies are required to assess the relationship between the BMI and crypts.

Limitations

Several limitations associated with the present study warrant mention. This was a single-center retrospective study that lacked information on genetic variations and had a relatively small sample size. However, more than half of the previous reports on the prevalence of LV crypts were studies of 300 cases, so the prevalence in our study is similar to that in larger studies.

Conclusion

The incidence of myocardial crypts in our study was similar to that reported previously. However, the most common location, the LV apex, differed from the earlier findings.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1.Teare D. Asymmetrical hypertrophy of the heart in young adults. Br Heart J 20: 1-8, 1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuribayashi T, Roberts WC. Myocardial disarray at junction of ventricular septum and left and right ventricular free walls in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 70: 1333-1340, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whittaker P, Romano T, Silver MD, Boughner DR. An improved method for detecting and quantifying cardiac muscle disarray in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J 118: 341-346, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Germans T, Wilde AA, Dijkmans PA, et al. Structural abnormalities of the inferoseptal left ventricular wall detected by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in carriers of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutations. J Am Coll Cardiol 48: 2518-2523, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johansson B, Maceira AM, Babu-Narayan SV, Moon JC, Pennell DJ, Kilner PJ. Clefts can be seen in the basal inferior wall of the left ventricle and the interventricular septum in healthy volunteers as well as patients by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 50: 1294-1295, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maron MS, Rowin EJ, Lin D, et al. Prevalence and clinical profile of myocardial crypts in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 5: 441-447, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petryka J, Baksi AJ, Prasad SK, Pennell DJ, Kilner PJ. Prevalence of inferobasal myocardial crypts among patients referred for cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 7: 259-264, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Child N, Muhr T, Sammut E, et al. Prevalence of myocardial crypts in a large retrospective cohort study by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 16: 66, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erol C, Koplay M, Olcay A, et al. Congenital left ventricular wall abnormalities in adults detected by gated cardiac multidetector computed tomography: clefts, aneurysms, diverticula and terminology problems. Eur J Radiol 81: 3276-3281, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brouwer WP, Germans T, Head MC, et al. Multiple myocardial crypts on modified long-axis view are a specific finding in pre-hypertrophic HCM mutation carriers. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 13: 292-297, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basso C, Marra MP, Thiene G. Myocardial clefts, crypts, or crevices: once again, you see only what you look for. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 7: 217-219, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sigvardsen PE, Pham MHC, Kühl JT, et al. Left ventricular myocardial crypts: morphological patterns and prognostic implications. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 22: 75-81, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arow Z, Nassar M, Monakier D, et al. Prevalence and morphology of myocardial crypts in normal and hypertrophied myocardium by computed tomography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 35: 1347-1355, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deva DP, Williams LK, Care M, et al. Deep basal inferoseptal crypts occur more commonly in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy due to disease-causing myofilament mutations. Radiology 269: 68-76, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy V, Korcarz C, Weinert L, Al-Sadir J, Spencer KT, Lang RM. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 98: 2354, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cresti A, Cannarile P, Aldi E, et al. Multimodality imaging and clinical significance of congenital ventricular outpouchings: recesses, diverticula, aneurysms, clefts, and crypts. J Cardiovasc Echogr 28: 9-17, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urbano-Moral JA, Gutierrez-Garcia-Moreno L, Rodriguez-Palomares JF, et al. Structural abnormalities in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy beyond left ventricular hypertrophy by multimodality imaging evaluation. Echocardiography 36: 1241-1252, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Captur G, Lopes LR, Mohun TJ, et al. Prediction of sarcomere mutations in subclinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 7: 863-871, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Velde N, Huurman R, Hassing HC, et al. Novel morphological features on CMR for the prediction of pathogenic sarcomere gene variants in subjects without hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Front Cardiovasc Med 8: 727405, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohlow MA, von Korn H, Lauer B. Characteristics and outcome of congenital left ventricular aneurysm and diverticulum: analysis of 809 cases published since 1816. Int J Cardiol 185: 34-45, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakamoto T, Tei C, Murayama M, Ichiyasu H, Hada Y. Giant T wave inversion as a manifestation of asymmetrical apical hypertrophy (AAH) of the left ventricle. Echocardiographic and ultrasono-cardiotomographic study. Jpn Heart J 17: 611-629, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi H, Ishimura T, Nishiyama S, et al. Hypertrophic nonobstructive cardiomyopathy with giant negative T waves (apical hypertrophy): ventriculographic and echocardiographic features in 30 patients. Am J Cardiol 44: 401-412, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson KM, Johnson HE, Dowe DA. Left ventricular apical thinning as normal anatomy. J Comput Assist Tomogr 33: 334-337, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto K, Mori S, Fukuzawa K, et al. Revisiting the prevalence and diversity of localized thinning of the left ventricular apex. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 31: 915-920, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]